Published online Aug 16, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i23.6816

Peer-review started: January 26, 2021

First decision: April 25, 2021

Revised: May 8, 2021

Accepted: June 22, 2021

Article in press: June 22, 2021

Published online: August 16, 2021

Neuroblastoma (NB) is one of the most common malignancies in children. Metastasis in NB is not uncommon. However, nasal metastases are rare. Here, we reported two pediatric cases of nasal metastases.

Case 1 was a 3-year-old boy without a history of NB. Case 2 was a 10-year-old girl who had a history of NB for 6 years. Both of them presented with symptoms of nasal and sinus masses such as epistaxis or discharge from the nose. The radiologic imaging results revealed masses in the nasal cavity or nasopharynx in both cases and a mass in the right adrenal gland of case 1. The pathologic examination of biopsy samples of their nasal masses revealed “small round blue-cell tumor” along with abundant vascular fibrous septa. The tumor cells expressed synaptophysin, cluster of differentiation 56, chromogranin A, paired like homeobox protein 2B and a very high Ki67 index in both case but were negative for vimentin, desmin, leucocyte common antigen and cytokeratin. Myelocytomatosis viral related oncogene, neuroblastoma derived (MYCN) amplification was detected in both cases. Finally, the two cases were diagnosed as nasal metastases from NB based on the clinical and pathologic findings. The two patients affected by NB were > 18 mo old, the primary tumor location was adrenal gland, and they presented with multiple metastases.

It is difficult to differentiate between metastatic NB in the nose and olfactory neuroblastoma in the absence of a history of NB. Paired like homeobox protein 2B can play an important role in the diagnosis and differential diagnosis of this disease.

Core Tip: Nasal metastases from neuroblastoma (NB) is a rare disease that can be misdiagnosed in case of initial presentation with a nasal mass without a history of NB. In this study, we reported two pediatric cases of nasal metastases including one case without a history of NB. It can be difficult to differentiate between metastatic NB in the nose and olfactory neuroblastoma in the absence of a history of NB. Paired like homeobox protein 2B is very helpful for accurate diagnosis.

- Citation: Zhang Y, Guan WB, Wang RF, Yu WW, Jiang RQ, Liu Y, Wang LF, Wang J. Nasal metastases from neuroblastoma-a rare entity: Two case reports. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(23): 6816-6823

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i23/6816.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i23.6816

Neuroblastoma (NB) is one of the most common malignancies in children[1], and its incidence is approximately 9.1-10.0 per million children (< 18 years) per year in some Western countries[1-3]. In some studies, approximately 53%-58% of patients have metastasis upon diagnosis[2-4]. However, nasal metastases are rare, and only one case has been reported to date[4,5]. Given that the low incidence and the morphological characteristics and immunohistochemical results of NB overlap with those of other nasal primary tumors such as olfactory neuroblastoma[1,6,7], nasal metastases from NB is prone to be misdiagnosed, particularly when this disease initially presents with a nasal mass without a history of NB. Two cases of nasal metastases from NB were retrospectively analyzed to raise awareness of this disease.

Case 1: A 3-year-old boy presented with the chief complaint of a painless mass on the left neck for 20 d and frequent epistaxis from the right nose for 10 d without any obvious cause.

Case 2: A 10-year-old girl presented with the chief complaint of right nasal congestion and discharge with blood from the right nose for about a week without any obvious cause. She had a history of NB 6 years ago.

Case 1: The patient presented with a painless mass on the left neck for 20 d and frequent epistaxis from the right nose for 10 d without any obvious cause in March 2013. Nasal endoscopy examination showed a mass in the right nasal cavity.

Case 2: The patient presented with right nasal congestion and discharge with blood from the right nose for about a week without any obvious cause in November 2017. Nasal endoscopy examination showed a mass in the right nasal cavity.

Case 1: The patient denied any history of past illness.

Case 2: The patient was diagnosed at 4 years of age with poorly differentiated NB in the right adrenal area with bone marrow metastases in December 2011 in our hospital. Then she received high-dose chemotherapy (cyclophosphamide + topotecan + doxorubicin + vincristine + cisplatin + etoposide) from December 2011 to June 2012. Surgical resection was performed in April 2012. Radiotherapy was administered in May 2012 (DT39.6/12) and December 2012 (DT39.6/10). However, retroperitoneal lymph node metastases were detected in April 2013 at 1 year after surgical resection. Chemotherapy (cyclophosphamide + topotecan + doxorubicin + vincristine + cisplatin + etoposide) was again administrated from May 2013 to December 2013. Stem cell transplantation chemotherapy was administrated in November 2015 when she was in complete remission after more than 1 year of follow-up. However, bone (bilateral tibia and fibula) metastases were detected in June 2016, and therefore chemotherapy (cyclophosphamide + topotecan + doxorubicin + vincristine + cisplatin + etoposide) was again administrated from June 2016 and June 2017. She was then followed in the clinic from July 2017 to now.

Case 1: The patient denied any family history.

Case 2: The patient denied any family history.

Case 1: A painless mass on the left neck was detected, which was round, moderately hard with a clear border and measured 0.5 cm in diameter.

Case 2: No specific finding was detected.

Case 1: Blood tests showed decreased white blood cell count, hemoglobin level and platelet count at 3.07 × 1012/L, 87 g/L, and 87 × 109/L, respectively.

Case 2: Blood tests showed elevated neutrophilic granulocyte percentage at 79.2%.

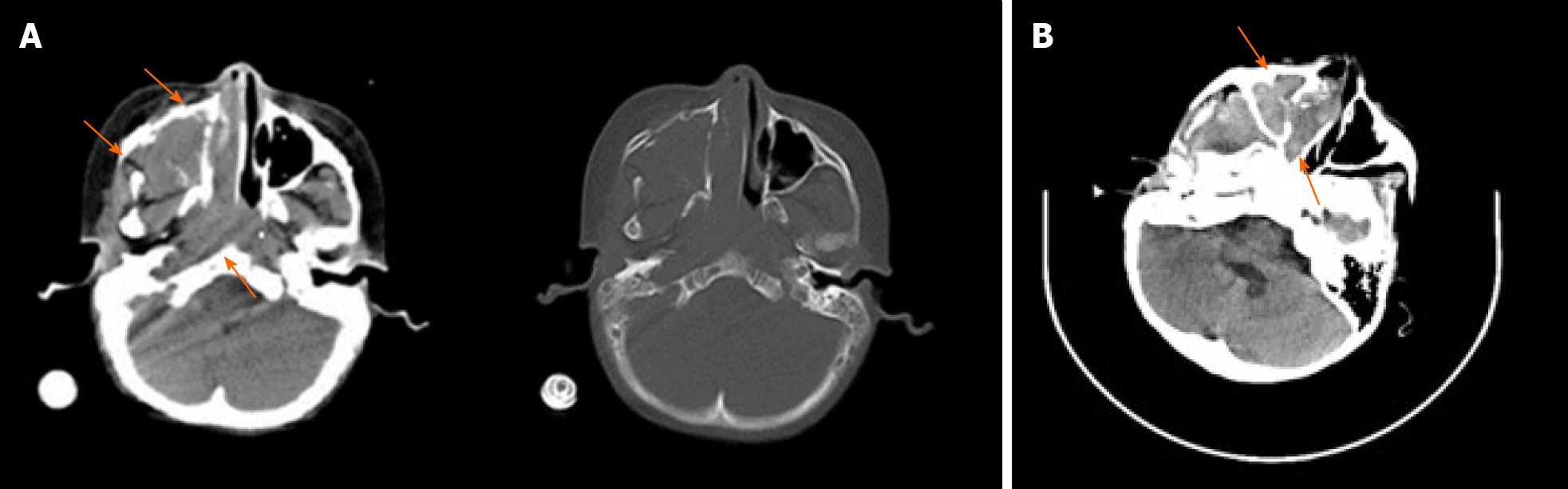

Case 1: A dual-source computed tomography scan and magnetic resonance imaging revealed masses in the right maxillary sinus, nasal cavity and nasopharynx (Figure 1A). Abdominal B-ultrasound revealed a big mass in the right adrenal gland and multiple nodules in the liver after the biopsy of the nasal mass.

Case 2: Enhanced computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging revealed a mass in the right nasal cavity (Figure 1B).

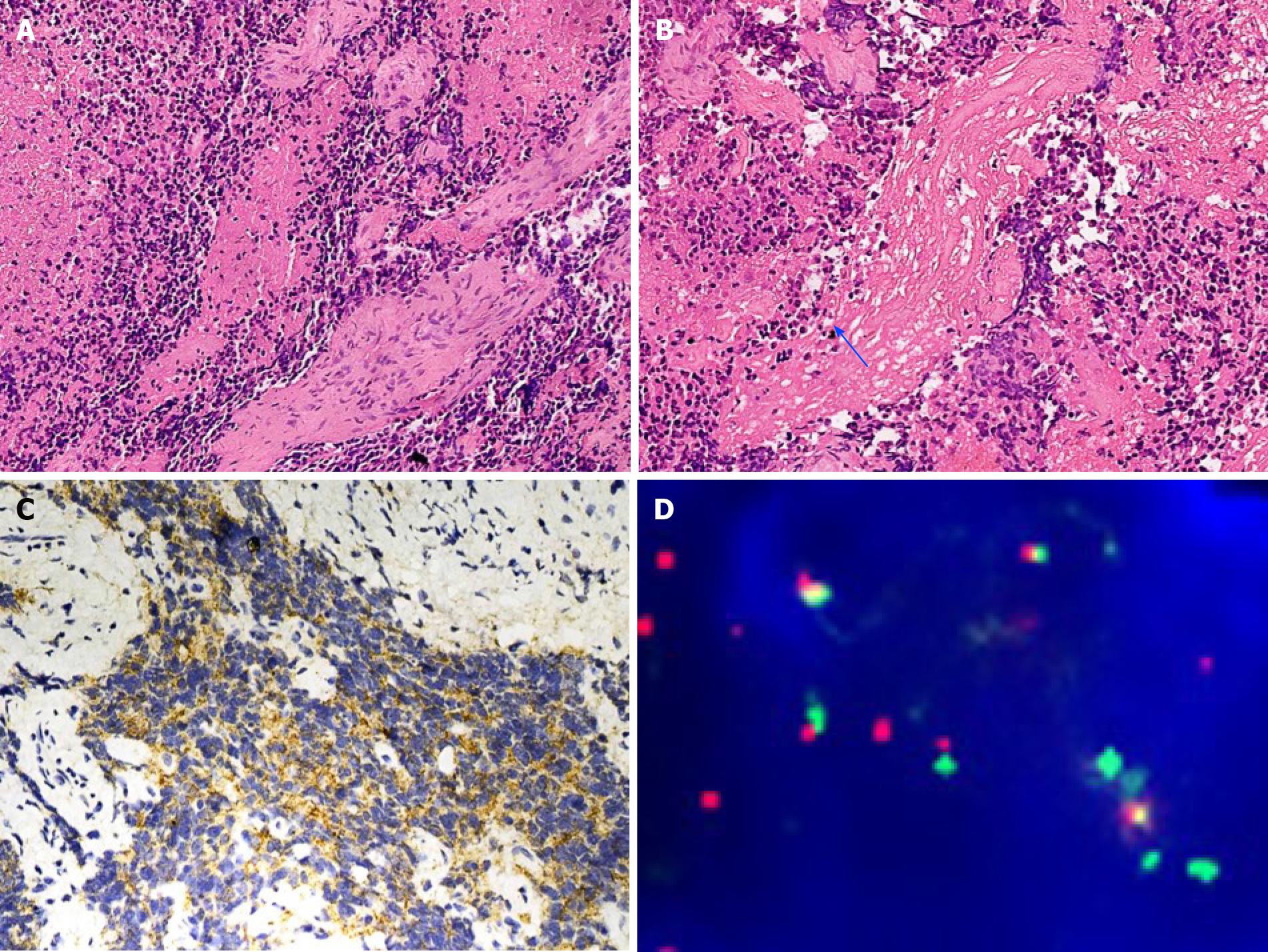

Case 1: The gross appearance of biopsy specimen were a few tan-brown or gray-white, irregularly shaped soft tissue fragments. The specimen measured 0.5 cm. The microscopy examination revealed poorly differentiated tumor, which was composed of small round blue cells separated by abundant vascular fibrous speta (Figure 2A). The tumor showed a cluster appearance with nest and rosette structures. Neuropil-like structures were found (Figure 2B). The mitotic figure count was approximately 1-2/10 high-power fields, and massive necrosis occurred. Immunohistochemically, the tumor cells in both cases expressed synaptophysin, cluster of differentiation 56 and chromogranin A (Figure 2C) but were negative for vimentin, desmin, leucocyte common antigen and cytokeratin. Myelocytomatosis viral related oncogene, neuroblastoma derived (MYCN) amplification (Figure 2D) was detected in case 1 through fluo

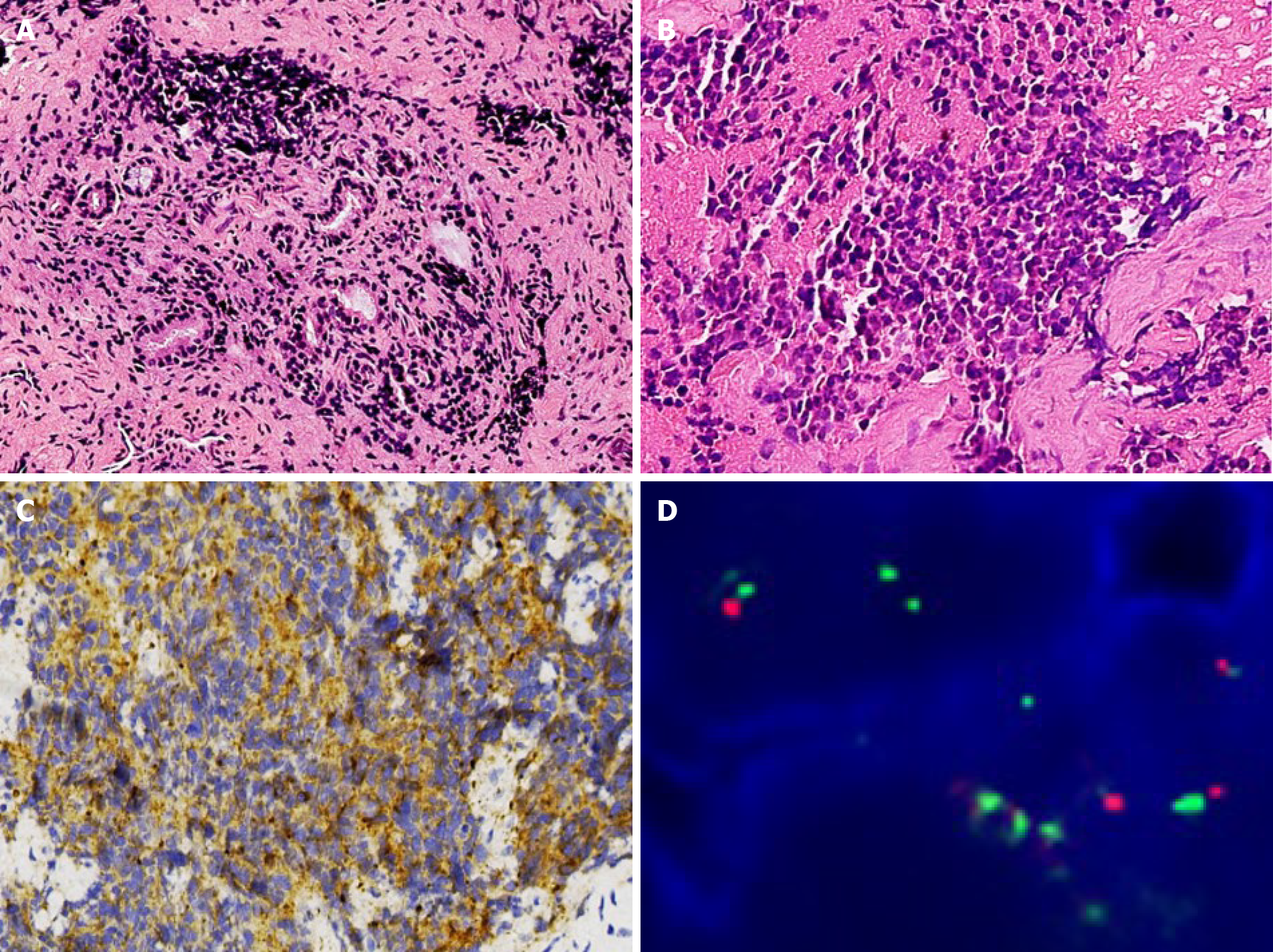

Case 2: The gross appearance of biopsy specimen of case 2 was similar to that of case 1, which were a few tan-brown or gray-white, irregularly shaped soft tissue fragments. The specimen measured 1 cm in diameter. The microscopic findings of case 2 were also similar to that of case 1. The microscopy examination revealed poorly differentiated tumors, which were composed of small round blue cells (Figure 3A). The tumors showed a cluster appearance with nest and rosette structures. The round or ovoid tumor cells displayed a scarce cytoplasm, round or ovoid cell nuclei with even sizes, thin chromatin and nonobvious nucleoli (Figure 3B). The results of immunohistochemistry assay in case 2 were the same to those in case 1. The tumor cells expressed synaptophysin, cluster of differentiation 56 and chromogranin A (Figure 3C) but were negative for vimentin, desmin, leucocyte common antigen and cytokeratin. MYCN amplification was also detected in case 2 through fluorescence in situ hybridization (Figure 3D). All the pathological results were examined by three pathologists.

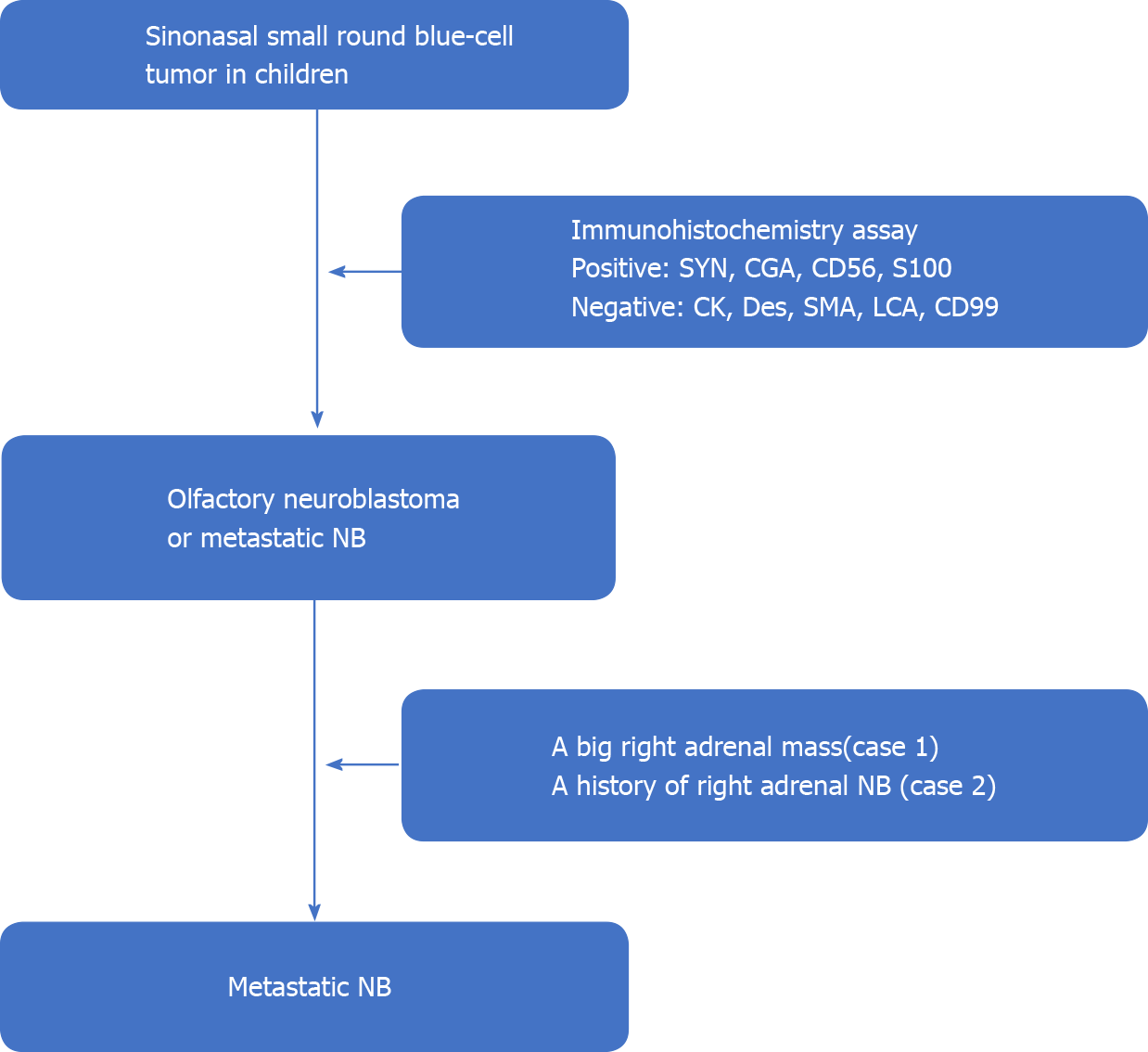

Case 1: The tumor was initially considered as olfactory neuroblastoma, but the final diagnosis was corrected as nasal metastases from NB after abdominal B-ultrasound revealed a big mass in the right adrenal gland and multiple nodules in the liver (Figure 4).

Case 2: A diagnosis of nasal metastases from NB was quickly pronounced based on the pathologic results and her NB history (Figure 4).

Case 1: The patient underwent a biopsy of the nasal masses. However, after the diagnosis of NB with multiple metastases including nasal metastases was pronounced, the patient refused to receive any treatment because of economic factors.

Case 2: The patient underwent a biopsy of the nasal masses. She received high-dose chemotherapy (temozolomide + irinotecan) in November and December 2017 and radiotherapy (DT39.6Gy/22Fx) in February 2018 after the diagnosis of nasal metastases from NB.

Case 1: The patient died 1 mo after the diagnosis.

Case 2: The patient died 12 mo after the diagnosis.

NB is one of the most common malignancies in children[1], and “the second-most common solid tumor of children”[6]. This tumor seems to occur in any location of the sympathetic nervous system[8]. Therefore, it often presents as a mass in the abdomen, retroperitoneum, pleural cavity or neck causing various symptoms, such as hyperten

The high-risk group not only shows a low rate of cure but also has distant metastasis and/or MYCN amplification[10]. The cancer in these patients metastasizes rapidly and spreads extensively. The metastatic locations include lymph nodes, bone marrow, bone, liver, skin/subcutaneous tissue and other locations[1,4]. Among them, the nose is rare[4,5]. Only one case has been reported so far[4,5]. The patients of the case together with our two cases were all > 18 mo old at the initial diagnosis, and the primary tumor location in each case was the adrenal gland (Table 1). The previous case report of nasal metastases from NB did not report immunohistochemical and molecular detection results[5]. However, the two patients in our report displayed MYCN amplification. These characteristics were the same as some of the high-risk factors of NB patients with a poor prognosis, which include age at diagnosis > 18 mo, adrenal gland as the primary location, molecular changes (MYCN amplification, segmental chromosomal alteration and diploidy) and increased lactate dehydrogenase blood levels[10]. Indeed, all three patients died within 2 years after the diagnosis of nasal metastases. Therefore, nasal metastases might be a clinical presentation at the late stage of NB and an indicator of poor prognosis.

| Series number | Age at initial diagnosis in yr | Age at nasal metastasis in yr | Gender | Primary tumor location | Surgery on the primary focus | Chemotherapy | Other therapy | Survival time after nasal metastasis in mo |

| 1[5] | 3 | 8 | Male | Adrenal gland | Yes | Yes | No | 24 |

| 2 (Case 1) | 3 | 3 | Male | Adrenal gland | No | No | No | 1 |

| 3 (Case 2) | 3 | 10 | Female | Adrenal gland | Yes | Yes | Radiotherapy, Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation | 12 |

With NB history, metastatic NB in the nose is not difficult to be diagnosed. However, if a nasal mass is the first symptom, the diagnosis becomes challenging. Clinical presentations such as nasal congestion and epistaxis are similar to those of nasal primary tumors, such as NK/T cell lymphoma, embryonic rhabdomyosarcoma and olfactory neuroblastoma. In our report, case 1 presented with frequent epistaxis from the right nose and a lymphoma or hemangioma diagnosis was considered in clinics. In general, pathological findings can favor the diagnosis; however, the morphological characteristics and immunohistochemical results of olfactory NB overlap with those of NB[1,7], so differentiating between them in a biopsy sample is difficult if only based on pathological findings. Both of them could form nests and rosette structures with a fibrovascular septa[1,7]. The tumor cells of NB are round and oval with dispersed chromatin, and the nucleoli are not obvious, resembling those of olfactory neuroblastoma[1,7]. Ganglion cells could even be detected in the two tumors[1,7]. In addition, specific immunohistochemical markers for them are lacking. The immunohistochemical results of NB revealed cluster of differentiation 56, synaptophysin and chromogranin A expression, which was also positive in olfactory neuroblastoma. Case 1 in our report was considered as olfactory neuroblastoma before a big mass was detected in the right adrenal gland.

Recently, it was found that paired like homeobox protein 2B (PHOX2B) was a relatively specific immunohistochemical marker of NB[11]. The wild-type PHOX2B gene is an important neurodevelopmental gene[11], and the PHOX2B protein participates in the development of the peripheral nervous system[11]. As a neural crest-derived marker, its expression in the tumors of the autonomic nervous system origin (NB, pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma) has relatively high sensitivity and specificity[12-14]. In NB, PHOX2B has high specificity in primary (96%–98% positive rate) and treated (94% positive rate) NB[9] and can be used to identify small residual and bone marrow metastatic NB lesions (87% positive rate)[9,15]. In our practice, most cases of NB express PHOX2B, whereas olfactory neuroblastoma does not. PHOX2B analysis was performed on the two cases of our report, which was not in the NB immunohistochemistry panel during diagnosis. Both of them were positive for PHOX2B (Figure 5). Therefore, the immunohistochemistry of PHOX2B can help differentiate NB from olfactory neuroblastoma.

Nasal metastases from NB are rare. This condition may be a clinical presentation at the late stage of NB. Differentiating it from olfactory neuroblastoma in a biopsy sample is difficult if only based on pathological findings. PHOX2B, a new immunohistochemical marker, is very helpful for accurate diagnosis.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Oncology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Munoz M, Shahini E, Tran MT S-Editor: Liu M L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Lack EE. Neuroblastoma, ganglioneuroblastoma, and other related tumors. In: Tumors of the Adrenal Glands and Extraadrenal Paraganglia, AFIP Atlas of Tumor Pathology Series 4 Fascicle 8. 1st ed. Washington, DC: American Registry of Pathology, 2007: 435-450. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Tas ML, Reedijk AMJ, Karim-Kos HE, Kremer LCM, van de Ven CP, Dierselhuis MP, van Eijkelenburg NKA, van Grotel M, Kraal KCJM, Peek AML, Coebergh JWW, Janssens GOR, de Keizer B, de Krijger RR, Pieters R, Tytgat GAM, van Noesel MM. Neuroblastoma between 1990 and 2014 in the Netherlands: Increased incidence and improved survival of high-risk neuroblastoma. Eur J Cancer. 2020;124:47-55. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 25] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Youlden DR, Jones BC, Cundy TP, Karpelowsky J, Aitken JF, McBride CA. Incidence and outcomes of neuroblastoma in Australian children: A population-based study (1983-2015). J Paediatr Child Health. 2020;56:1046-1052. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Steliarova-Foucher E, Colombet M, Ries LAG, Moreno F, Dolya A, Bray F, Hesseling P, Shin HY, Stiller CA; IICC-3 contributors. International incidence of childhood cancer, 2001-10: a population-based registry study. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:719-731. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 910] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 810] [Article Influence: 115.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ogawa T, Hara K, Kawarai Y, Nishizaki K, Nomiya S, Takeda Y, Akagi H, Kariya S. A case of infantile neuroblastoma with intramucosal metastasis in a paranasal sinus. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2000;55:61-64. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Conran RM, Chung E, Dehner LP, Shimada H. The pineal, pituitary, parathyoid, thyoid, and adrenal glands. In: Stocker & Dehner's Pediatric Pathology. 3rd ed. Philadephia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2010: 957-970. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Mills SE, Stelow EB, Hunt JL. Neural, neuroendocrine, and neuroectoderma neoplasia. In: Tumors of the Upper Aerodigestive Tract and Ear, AFIP Atlas of Tumor Pathology Series 4 Fascicle 17. 1st ed. Silver Spring, Maryland: American Registry of Pathology, 2012: 201-211. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Jiang M, Stanke J, Lahti JM. The connections between neural crest development and neuroblastoma. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2011;94:77-127. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 101] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hata JL, Correa H, Krishnan C, Esbenshade AJ, Black JO, Chung DH, Mobley BC. Diagnostic utility of PHOX2B in primary and treated neuroblastoma and in neuroblastoma metastatic to the bone marrow. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2015;139:543-546. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 26] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ambros PF, Ambros IM, Brodeur GM, Haber M, Khan J, Nakagawara A, Schleiermacher G, Speleman F, Spitz R, London WB, Cohn SL, Pearson AD, Maris JM. International consensus for neuroblastoma molecular diagnostics: report from the International Neuroblastoma Risk Group (INRG) Biology Committee. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:1471-1482. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 267] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 255] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Raabe EH, Laudenslager M, Winter C, Wasserman N, Cole K, LaQuaglia M, Maris DJ, Mosse YP, Maris JM. Prevalence and functional consequence of PHOX2B mutations in neuroblastoma. Oncogene. 2008;27:469-476. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 113] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Brunet JF, Pattyn A. Phox2 genes - from patterning to connectivity. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2002;12:435-440. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 183] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 191] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Mosse YP, Laudenslager M, Khazi D, Carlisle AJ, Winter CL, Rappaport E, Maris JM. Germline PHOX2B mutation in hereditary neuroblastoma. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75:727-730. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 184] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 185] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Bielle F, Fréneaux P, Jeanne-Pasquier C, Maran-Gonzalez A, Rousseau A, Lamant L, Paris R, Pierron G, Nicolas AV, Sastre-Garau X, Delattre O, Bourdeaut F, Peuchmaur M. PHOX2B immunolabeling: a novel tool for the diagnosis of undifferentiated neuroblastomas among childhood small round blue-cell tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:1141-1149. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 38] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Stutterheim J, Gerritsen A, Zappeij-Kannegieter L, Kleijn I, Dee R, Hooft L, van Noesel MM, Bierings M, Berthold F, Versteeg R, Caron HN, van der Schoot CE, Tytgat GA. PHOX2B is a novel and specific marker for minimal residual disease testing in neuroblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5443-5449. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 70] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |