From Castilian to Nahuatl, or from Nahuatl to Castilian? Reflections and Doubts about Legal Translation in the Writings of Judge Alonso de Zorita (1512–1585?)

Introduction

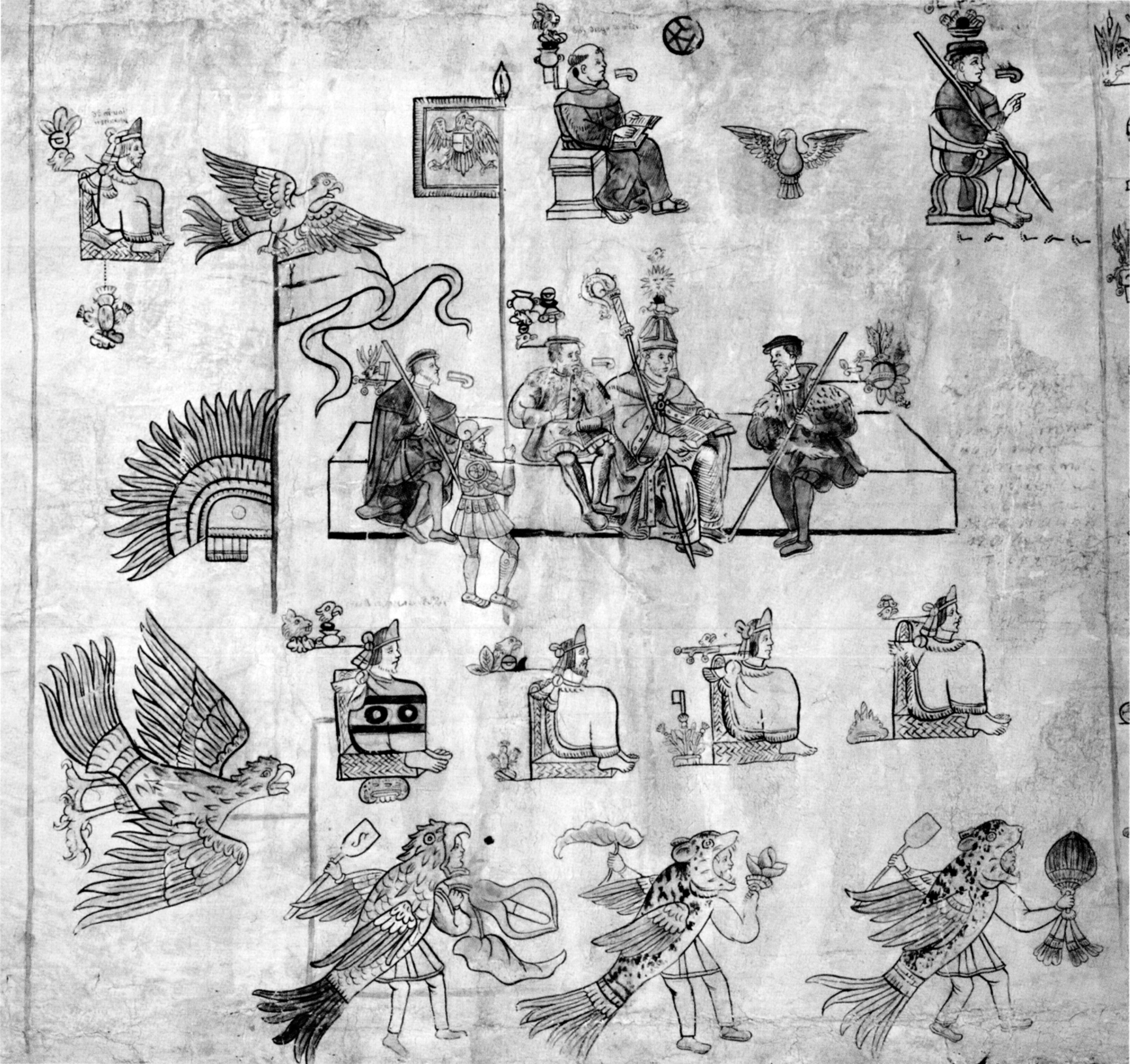

On June 6th, 1556, a great ceremony took place in the city of Mexico celebrating Philip II’s ascension to the throne; after the abdication of his father, Charles I of Spain, some months prior, he had become king of Castile. In one of the images belonging to the Tlatelolco Codex1 (illustration #8), an anonymous painter illustrated the oath of allegiance administered to King Philip II2 by native noblemen (the caciques of Tlatelolco, Mexico-Tenochtitlan, Tacuba, and Tezcoco squatting in the third row of figures depicted in the Codex), the main Spanish authorities in the city of Mexico, and in the Viceroyalty of New Spain (viceroy Luis de Velasco, archbishop Alonso de Montúfar, and the judges of the Audience of Mexico, sitting on a platform in the second row), as well as prominent members of the secular and regular clergy (some of them depicted in the first row).

For the Indian population of the city of Mexico, it was an occasion to welcome their new king in accordance with their ceremonial traditions. For this special occasion, mitotes were authorized. Mitote is a theological-political dance and form of preaching that the natives used to wish their lords in the pre-Hispanic era a good reign, while, at the same time, asking their gods for good weather and beneficial agricultural conditions under the rule of the new tlatoani.3 Mitote dancers appear in the lowest row of figures depicted in illustration #8 of Tlatelolco Codex.

Elements such as the way authorities and noblemen are portrayed,4 the representation of political and religious ideas using symbols – for instance, birds and clothing –, and even the expression of joy and love to the new monarch during the oath of allegiance, differ according to the identity and the rank of the persons depicted by the anonymous pictorial chronicler. Nevertheless, as a whole, the | representation of this public ceremony also expresses a kind of common order, a kind of mestizo system of rule, where Mexican natives and Spaniards come together to perform an act of collective submission to a distant monarch. His ascension to the throne was precisely the reason or pretense for this meeting; a ceremony where two different hierarchical thoughts, religious beliefs, and symbolic patterns were carefully taken into account by the organizers and participants. The author of this part of the Tlatelolco Codex depicted all of these elements in an image of 16th century Mexico constructed as a unity in diversity and expressing, above all, the legal nature of a system of domination based on the interaction – even if unequal and, more often than not, conflict-ridden – between two social, religious, and legal cultures.

The image from the ca. 1562 depicted Tlatelolco Codex could be considered a good example of thecultural hybridization5 that we have to take into account when talking about the complex dynamics of cultural and legal translation, especial | ly in 16th century New Spain. It depicts, on the one hand, a very specific oath of allegiance that serves as an example of the distinctive way in which Spanish and Western juridical and political frameworks were introduced into the Mexican high plateau soon after the conquests headed by Cortés and other Spanish captains. On the other hand, we can consider it an interesting and illustrative point of departure for reflecting on the complexities of such a process of translation and redefinition in complex societies already endowed with a legal tradition, such as that of the Nahua.

The kind of images depicted in the Tlatelolco Codex – above all, a traditional Native American way of juridical and historical representation adapted to the political context of the early decades of Spanish domination – encourage us to reformulate and revise previous ideas about the translation of laws and norms from Europe to America in the early modern period; a process often understood as a movement in one direction that consisted in the mere transplantation of European concepts and normativity into the empty spaces of the recently discovered American continent.6 Consciously avoiding, on the other hand, an irenic vision of the so-called »encounter between two worlds,«7 elements, such as the persistence of native ways of political and ceremonial representation (also important in the case of pictorial juridical sources for the Nahua region, as specialists in the field have pointed out studying litigation about land ownership and tributes8) and the important role played by native authorities in the administration of the land after the Spanish conquest, allows us to speak of a translation process moving in both directions. From this point of view, we can reflect not only on the extensive translation of European or Castilian normativities into the Viceroyalty of New Spain during the first decades of Spanish domination,9 but also about the complex ways in which the highly developed Nahua juridical and institutional culture influenced the legal evolution in the Mexican high plateau – at least in 16th century.

In this article, I will focus on several writings and legal projects of a 16th century Spanish jurist, who better represents the creative dimension inspiring some of the proposals for adaptation of Castilian law to native legal custom in order to avoid what Gunther Teubner, reflecting on legal transfers between contemporary juridical systems, has called legal irritants.10 I am referring to the licenciado Alonso de Zorita, oidor of the Audience of Mexico from 1556 to 1566. After a short introductory biography of Alonso de Zorita, which I consider necessary in order to understand how his juridical formation and experience as oidor in the Audiences of La Española, Guatemala, and Mexico helped him to offer a synthetic legal perspective of previous accounts on pre-Hispanic fiscal systems11 in the Nahua region and the Americas, I will refer | to some cédulas-questionnaires addressed by the Council of the Indies to Spanish officers in the Americas since the 1550s. This legislation encouraged the continued search for information about the topic. Using the contemporary conceptual framework on cultural translation developed by Peter Burke12 and applied to studies on legal history by contemporary scholars such as Duve and Foljanty,13 I will show how in this area and period a systematic knowledge of the context (population, customs, territories, resources, etc.) into which law needed to be introduced was (often) considered an indispensable preliminary step to providing good legislation. In the third and final part of the contribution, I will analyze the way in which Zorita, at the same time participant and critic of the movement initiated by the Council of the Indies in the 1550s, shared the general awareness of the need for a better understanding of Indian societies and customs, yet distanced himself from the homogenizing perspective prevalent in this influential institution, which was then followed in the 17th and 18th centuries by Solórzano and other prominent theoreticians of derecho indiano. While Ovando, López de Velasco, previous jurists, and royal officers merely wanted to know more about Indian societies and their cultural values in order to better understand the context into which Castilian law had to be translated, Zorita used the above-mentioned cédula to subvert previous approaches as well as to propose a very different means to build a harmonious legal system in the New World: the restoration of an idealized pre-Hispanic system of rule and social division. In this final section, I will specifically reflect on the linguistic issues implied by the choice of legal sources Zorita made use of. Here, the focus will be on the means he used (pictorial legal sources of the natives, interpreters, and translators) to obtain precise and first-hand information about the political and fiscal traditions he proposed to restore.

Alonso de Zorita is, indeed, one of the authorities represented in illustration #8 of the Tlatelolco Codex. He is depicted sitting on the left-hand side of the platform occupied by the main Spanish authorities in New Spain. The scepter of justice that Zorita holds in his right hand indicates his office, while the glyph in front of his head tell us that he gave an speech during the ceremony.

Zorita’s major works were published in two important critical editions14 at the turn of the century, thus setting the stage for future research. Legal and social historians, such as Andrés Lira15 and Ethelia Ruiz, and even social anthropologists, such as Wiebke Ahrndt, have since made important contributions to our knowledge about Zorita’s life and writings, thereby representing an improvement over previous books16 dedicated to one of the most prominent figures in Spanish American Colonial Law. Nevertheless, a focus on the importance of Zorita’s writings from the perspective of translation studies has never been undertaken.

Zorita, appointed as oidor of the Audience in 1556, wrote between the end of the 1560s (while already retired in Spain) and 1585, a Breve y sumaria relación de los señores de la Nueva España. It was a response addressed to a much earlier cédula or royal instruction issued in 1553, in which Felipe II asked the president and oidores of the Audience of New Spain for information comparing both the kind and amount of taxes the Indians paid under Moctezuma’s reign as well as under the rule of the encomenderos. Up to that point, no other Spanish officer in the Americas had provided such extensive information and details about the fiscal customs of | Amerindian peoples prior to the Spanish conquest. Zorita’s Breve relación and his other writings17 reflect, on the one hand, the debates and different perspectives about a better way of translating European legal frameworks and traditions into the New World. On the other, it is related to the inquiries about indigenous fiscal and political customs instigated by the Spanish Monarchy in the second half of 16th century, and to the partial appropriation of this consuetudinary law that can be observed in the daily work of some Spanish judges and other royal officers since this period.18

The specific field of Zorita’s research was fiscal law: an area in which he made major contributions with his numerous important descriptions and interpretations of the tributary systems of the natives of the Mexican high plateau, other territories integrated to the Vice-royalty of New Spain, and different regions of what is today Colombia and Guatemala: areas in which he held different judicial offices from 1547 to 1556 (shortly before his arrival in Mexico). In general terms, he offered a positive perspective regarding the indigenous tributary systems (considered to be an idealized vision of the pre-Hispanic era by most of the scholars working on his accounts19). His descriptions have been associated with the Franciscan projects asking Spanish authorities for a complete recognition of pre-Hispanic socio-political structures and customs on taxation.20

With regard to certain aspects, Zorita’s Breve y sumaria relación is the best Spanish source we have for learning about the complex hierarchic system and customary laws of the pre-Hispanic Nahua region; a legal and political system that he described not only as being in accordance with natural law and the policy followed in the well-governed Christian republics, but also with regard to most of the prescriptions of the European canon and civil law.21 The value of Zorita’s work also stems from the fact that while writing his report, he had access to previous accounts treating the same topic written by Franciscan friars (Francisco de Las Navas, Andrés de Olmos,22 etc.) that have since been lost – reports that are remarkable for their accuracy in the use of Nahua terms.23

A Short Biographical Approach

Among the Spanish jurists in 16th century America, Zorita was one of the most experienced. By the time he retired at roughly the age of 55, he had acquired a great expertise about the northern and central territories of the Spanish Empire in the Americas. Upon returning to Spain,24 he dedicated himself to writing what would become his major works.

Both his family origins – with his father, the hidalgo Alonso Díaz de Zorita (relative of the prestigious Spanish captain Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba), being one of the jurists that helped to administer the city of Córdoba25 – and his studies in law26 at the prestigious University of Salamanca served as an important preparation for becoming a judge. Zorita studied during one of the most prolific periods in the history of the University of Salamanca: between 1537–40. Experts on the School of Salamanca consider these years to be the starting point of the famous school of theology | and law. It was also a period in which the religious, moral, and political dilemmas arising from the conquest of the Indies were the subject of lectures and public debates at the University. Francisco de Vitoria, the most well-known theologian of the University of Salamanca in early modern times, held, at the end of the 1530s, the chair of theology and delivered two important and transcendent lectures (Relectio de Indis, Relectio de Iure Belli) on these topics.27 Even if it is very improbable that the young Zorita – a student at the Faculty of Law – attended Vitoria’s lectures,28 he certainly would have been aware of some of the issues dealt with by Vitoria and which would upon completing his training later comprise the core of his own work.

His first legal experience, acquired as abogado de pobres (solicitor for the poor) in the Audience of Granada – a poorly paid office, whose exercise by a noblemen having studied at Salamanca would certainly have seemed strange – can also be related to his later concern about the abuses and humiliations endured by the Indians. The miserable status29 accorded to Indians in Spanish American Law, in fact, closely resembled the juridical condition of the Spanish pobres. As such, it would be interesting to delve deeper into the professional tasks Zorita was occupied with in Granada before sailing to the Americas. It was often the case that such experiences were the very reason underlying the selection of a certain individual for a position in the Indies. In one way or another, it is pretty clear that this experience continued to inform the way Zorita understood and performed the tasks he was later assigned.

With regard to his legal career in America, Zorita obtained his first appointment as oidor in the Audience of La Española (May 1547).30 Zorita’s stay in Santo Domingo, the main city of the island La Española, was neither very long nor quiet. In January 1549,31 his colleagues at the Royal Audience appointed him the judge in charge of taking Miguel Díez de Armendáriz’s residencia32 (Díez was accused of many injustices and abuses of his power as governor of the New Kingdom of Granada). Considering the power wielded by Díez’s allies in the region, and in order to better accomplish this problematic assignment, he was even appointed governor of the New Kingdom of Granada by the Audience of La Española.33 Zorita stayed in the New Kingdom of Granada from January 1550 to May 1552. During this period, he visited a significant part of this South-American region. His travels included Santa Marta and Río de la Hacha (in the northern Caribbean Region, where he arrived from Santo Domingo), Santa Fe (present Bogotá, the main city of the New Kingdom, more than 1.000 kilometers southern to the Caribbean coast), Tocaima and Los Panches (on the long Magdalena river) and Cartagena (west of Santa Marta in the Caribbean coast). Everywhere he went, he encountered a determined resistance against taking Miguel Díez’s residencia. Reflecting on his travels some decades later while writing the Breve y sumaria relación,34 he recounted and denounced the substantial abuses inflicted on the Indians by the Spaniards.

After this turbulent residencia, Zorita received a new appointment as oidor in the Audience of Guatemala – another conflicted destination – in July 155235. Despite his work as oidor having been greatly appreciated by the most prominent inhabitants of Santo Domingo (integrated as vecinos in the Cabildo of the city), who even addressed a letter to the King asking the monarch to maintain Zorita as oidor of the Audience,36 Zorita again had to set sail and in the summer of 1553 arrived in Santiago de Guatemala. During his three years of service, he made three visitas, »traveling where no Spanish judge had ever been« and »corrected abuses, made head counts, and moderated tributes.«37 |

In April 1556, Zorita left Guatemala after being appointed oidor of the Audience of New Spain. It is a matter of interpretation if his nomination was to be considered a promotion (for the city of Mexico was much wealthier and comfortable than Santiago de Guatemala, at that time) or a way to lighten Guatemalan encomenderos of a very critical judge, who they considered a disruption from the very beginning.

Starting in 1556, Mexico became Zorita’s permanent residence, where he worked as oidor until 1566, when, being partially deaf and after almost 20 years in America, he decided to return to Spain and established himself in Granada. Zorita’s tasks in New Spain were closely related to the ones he had performed in Guatemala. Above all, he tried to elaborate stable and affordable assessments of the tributes that the Indians had to pay to encomenderos and other secular and religious authorities; moreover, he constantly advocated for a reduction of taxes for the native population. Zorita’s reflections clearly bear the stamp of the history of misfortune that occurred in the early decades of Spanish domination over Caribbean populations. He was well aware of the fact that fiscal abuses (in the forms of overtaxation and forcing the Indians to work under inhuman conditions) had led to the extermination of natives in La Española and in the northern regions of the New Kingdom of Granada.38 While he was working in Mexico, Zorita travelled a great deal and covered vast territories as part of the census he was assigned to conduct for the Crown and the Audience.39 The area where Zorita focused his activity was the central region of the country; a territory granted to Cortés in 1529 as a perpetual fief under the denomination of Marquesado del Valle de Oaxaca, a vast stretch of land including territories of the present-day Mexican states of Mexico, Michoacán, Morelos, Veracruz, and Oaxaca. The expansiveness of the region he had to »count« and supervise as well as the diversity of the native peoples given to Cortés as vassals and tributaries by the Spanish monarchy also influenced Zorita’s legal writings, which were filled with very specific information and anecdotes about lesser-known indigenous towns and populations that no other jurist of this period had been in a position to speak about.

Translation as Justice. The Recovery and Respect of Prehispanic Fiscal Customs as a sine qua non for a Legitimate Dominion over the Indies

As several scholars have shown, tributes were at the core of intense political debates in all of the kingdoms and republics of medieval and early modern Europe.40 Even Bodin, creator of the concept of sovereignty and clearly in favor of an absolutist royal government, expressed doubts in the 1570s about the legitimacy of establishing tributes without the consent of the subjects and contrary to kingdoms’ fiscal traditions in his Six livres de la République.41 In Zorita’s Breve y sumaria relación, we also find a clear denunciation of assessment made without the consent of the subjects (in this case, the Indian vassals of Philip II), a clear element of tyrannical rule. As we can see in the royal cédula of 1553, to which Zorita intended to respond,42 this was, in turn, taken into account by the jurists working in the Council of the Indies. The cédula (in article 12) expressly ordered the authorities of New Spain to provide specific infor | mation about the kind of public consultation that should have taken place prior to the assessment of the tributes in every indigenous town. Three decades later, Zorita attested sadly that during his time as judge at the Audience of Mexico (soon after the reception and implementation of the above-mentioned cédula), natives were »summoned for the sole purpose of being counted« and »given no opportunity to present their views.«43

From the perspective of the former judge of the Audience of Mexico, respect for the fiscal customs and the social order that indigenous people had at the time of their heathendom was the second sine qua non condition of a legitimate tax implementation and domination of the Spanish monarchs over the Western Indies. In his opinion, if Felipe II and his counselors support or tolerate fiscal abuse and unfair innovations in the tributary system of the Indian republics (as it was usually denounced by natives and its intermediaries in the Spanish Audiences in the New World), the initially fairly Spanish domination over America (established with the pious justification of teaching the Indians the Gospel) could deviate from its original purpose and degenerate into a tyrannical rule. From Zorita’s perspective, even if corruption and misgovernment have not yet influenced the system as a whole, a number of indigenous villages and towns could be considered tyrannical republics. They were indeed governed by usurpers,44 former macehuales45 not belonging to the lineages of native lords, established or supported by Spanish encomenderos in order to oppress the rest of the Indian commoners.

This kind of denunciation could have significant implications. According to the classical doctrines of the ius commune, both usurpation and fiscal tyranny – a kind of tyranny ex parte exercitio46 – could legitimately be resisted by oppressed subjects. Under certain conditions, it would even be permissible to kill the tyrant and his ministers (judges, soldiers, tax collectors, etc.) and search for military assistance from other kingdoms and republics (the rivals of the Spanish monarchy, in this case, who could also legitimately intervene to support native upheavals caused by overtaxation and misgovernment).

The consensus about these tributary ideas was so widespread in early modern Spain that not only defenders of the Indians, such as Las Casas and Zorita, appealed to them when asking for a reduction of the taxes for the natives, but also Hernán Cortés, whose interests and purposes were completely opposed to those alleged by the protectors of the Indians, referred to the tributary traditions of the Indians when he justified the kind of encomienda and personal services that he decided to implement, disobeying the instructions that Carlos V had addressed to him in 1523.47

The discussion of this topic was, of course, quite vehement at the University of Salamanca, where Zorita had studied. Since the early decades of the 16th century, theologians, such as Matías de Paz, have written treatises asking the Spanish kings for a fair taxation of the Indians. Zorita’s presence at the University of Salamanca offers an interesting element for interpreting his writings as an extensive legal application of the slight theological and political approach to the topic of Indians’ taxation made by some of the theologians usually associated with the School of Salamanca. Nonetheless, Zorita’s work should not be considered merely as a repetition of preceding doctrines. His writings represent by far one of the most complex and critical approaches to the matter of taxation in the Indies. He went beyond the proto-absolutist ideas that, first, Matías de Paz (in a small booklet redacted in 151248) and, later, Francisco de Vitoria (in his well-known De Indis Relectio Posterior, sive De Iure Belli, 1539, and in previous lectures on Saint | Thomas I-II 90–105 and II-II 10.8) had written on this topic.49

What we called a second condition of legitimate tax assessments – that is, respect of the fiscal customs and social order of the natives – was taken into account in the cédula of 1553, which was praised by Zorita for its fairness.50 From the perspective of the jurists of the Council of the Indies, fairness was, indeed, not incompatible with efficiency. The cédula explicitly urged Spanish authorities in New Spain to construct a system of tributes adapted to Indian customs and to enact forms and amounts of taxation that the Indians could pay without being forced to give up their most basic necessities.51 The members of the Council also evaluated taxation from a religious point of view; they considered the order by a Christian monarch to their subjects to pay higher taxes than that paid to their former Pagan rulers as a disgrace to the Christian religion. They referred to this theological dilemma as »a thing that matters very much to his majesty and is very convenient to the acquittal of his conscience.«52

At the core of a wide universe of opinions, Zorita’s writings are especially interesting not only with regards to contemporary politico-juridical debates about taxation and tyranny. Trying to reconstruct Nahua customary fiscal practices (and often providing supplementary information about the ones of the Americans regions where he had stayed), he considered them legitimate polices, which were completely in accordance with natural law. Going a step further than jurists and theologians before him, Zorita called for the same respect for customary laws belonging to all the kingdoms and republics integrated into the Spanish Monarchy (regardless of whether they were European or American). Moreover, he initiated a campaign in favor of the study and integration of pre-Hispanic forms of taxation in the legal system the Spaniards were building and implementing in New Spain and other regions of the Americas.

Zorita considered traditional taxation not only the most just form, but also the only form that could, in fact, be implemented in New Spain and the Indies. Only by limiting their own greed and drafting petitions according to the customs of the conquered lands could royal authorities establish sustainable fiscal systems in the Americas. From this perspective, approval and cooperation of native aristocracies (partially asked in the decades immediately following the conquest of Mexico) was considered absolutely necessary. Among the Nahuas, only the literate nobility had, for Zorita, the linguistic abilities required to interpret pre-Hispanic legal sources, a complete knowledge about what each land and group of vassals could produce and pay as tribute, and even the natural virtues needed to serve as the indispensable moral guides and procurators of their people. From a multi-normative point of view, Zorita considered moral and religious values as grounding elements in a commonwealth. Consequently, he pointed to the dethronement of natural lords/moral teachers and the corresponding interruption in the transmission of knowledge and values that followed as the most important cause of the political and social confusion prevailing in New Spain.53 A restoration of the previous harmonious order of the Nahua peoples would, therefore, only be possible if the | ancient dignity of natural lords were restored and they were made equal participants in a mestizo system of rule. In order to benefit from their valuable cooperation, Zorita identified respect for the jurisdiction and rights of taxation exerted by pre-Hispanic lords as another sine qua non condition for the success of the whole fiscal policy to be implemented in New Spain.54

While other Spanish jurists of the early modern period only made passing reference to the topic of Indian diversity, Zorita took this idea very seriously. And because of the attention he paid to pre-Hispanic legal customs, Zorita stood out from the other juristas indianos. For example, we find reflections in Solórzano’s writings55 about the extreme diversity of the regions in the Indies56 as an element justifying the elaboration of a specific derecho indiano as well as local legislation adapted to each of the major regions and populations of the New World. On the other hand, his Política Indiana (1648) and earlier works by other authors, such as the Ordinances of the Council of the Indies elaborated by Juan de Ovando (1571), state conclusively that the Indies, incorporated into the Castilian Crown in the form of an accessory union, »had to be governed, ruled and judged«57 by the same laws that were applied in Castile.

Distancing himself from jurists in favor of a homogenization between the American republics and Castile, Zorita did not even mention the problematic notion of accessory union.58 Instead, he considered legal customs to be one of the most relevant elements of the much-vaunted American diversity, exhorting his colleagues to take them into account in the process of creating new legislation. As a result of his almost 20 years of first-hand experience in the Americas, Zorita considered the proposed close translation of much of the contents of ius commune and Castilian laws into the Indies neither fair nor applicable.59 In his writings he advocated a totally different approach and, to the best of his abilities, tried to promote an inverse translation process: the translation of pre-Hispanic legal customs (regarding fiscal policy, social regulation, public order, etc.) into the, up till that point, slightly mestizo legal framework under construction in New Spain. |

The Cédulas and Questionnaires of the Period between 1553 and 1584. Instructions for a Broad Cultural Research and the Foundations of a Complex Process of Legal Translation

The objectives that the Crown and the Council of the Indies purported that the cédulas and questionnaires mentioned above were aiming at were, first, to gather strategic information about indigenous political hierarchy and legal customs, and, second, to use the results of the previously ordered historical and socio-economical inquiries to elaborate a fiscal policy partially based on Indian custom and benefiting from the consent of the governed. This was no easy task, for it was very difficult to build a system that aligned both the general economic objectives of Spanish tributary policy and the special care with which the taxation of natives and their compulsion to work had to be evaluated after the dramatic extermination of Taíno and Caribe peoples due to overwork and exhaustion. The violent rebellions and persistent critiques that encomenderos addressed at the fiscal laws contained in the Leyes Nuevas of 1542 (Gonzalo Pizarro’s rebellions in Peru, 1544–48, and Martín Cortés’ aborted plot in Mexico, 156660) contributed further dramatic tension to an already turbulent atmosphere.

The exact royal cédula mentioned by Zorita in the Breve y sumaria relación in order to justify »how this relation came to be written, and why it was not written until now,«61 was issued at Valladolid on December 20th, 1553.62 As Zorita pointed out in several letters addressed to the King and the members of the Council of the Indies, which served as an introduction to his work, the members of the Audiences of the Indies were basically ordered »to inquire who were the lords of the land, what tribute the natives paid them in the time of their heathendom, and what tribute they have been paying since they came under the Royal Crown of Castile.«63 In these introductory letters, Zorita apologized for responding to the royal orders so late. In fact, according to the current research on Zorita and his Relaciones, he finished his response to the petitions of the Crown in 1585, more than 30 years after the royal cédula mentioned above was originally issued. Taking this into account, both Wiebke Ahrndt and the legal historian Andrés Lira consider the Breve y sumaria relación to represent a very belated piece of advice. However, this advice was, in fact, no longer required by the Crown. Instead, it served as an opportunity for Zorita to once again impress upon the jurists of the Council of the Indies the importance of considering Indian legal customs.64

In accordance with his strategic motivations, Zorita could have quoted instructions and questionnaires about native tributes issued by the Spanish Monarchy some years before he concluded the drafting of his Relaciones. The kind of research stimulated by the Council of Indies with the cédula of 1553 became a trending topic after the visita and reorganization of the Council of Indies by the jurist Juan de Ovando, who was appointed president of this important institution in 1571. Even before his appointment to this prominent position (in 1569), Ovando elaborated and sent Spanish | officers and high-ranking clergymen in the Indies a 37 chapter questionnaire asking for descriptions of American provinces. This questionnaire was more sophisticated and detailed than the cédula of 1553.65 Later questionnaires addressed to secular and ecclesiastical authorities continued this refinement process, the complexity of which went hand in hand with the significant increase in the number of chapters.66 The cédulas signed by Felipe II in 1572 and 1573 (the important Provisión del bosque de Segovia) represented a royal endorsement of the inquiries ordered by Ovando.67 After his death in September 1575, Juan López de Velasco,68 appointed by Ovando as official chronicler and cosmographer, played an important role in the elaboration and dispatch (in 1577 and 1584) of new questionnaires and instructions. With regard to native customs and to the conditions under which the Indians were ruled and taxed before and after the arrival of the Spaniards, these were even more systematic than the preceding ones.69

The interest in ethnographical issues, pre-Hispanic history, and legal customs did not survive long after Ovando’s death. Fearing that the inquiries ordered might be used in anti-Spanish propaganda or arouse a dangerous sense of nostalgia among the literate Indian noblemen conducting some of the research, in 1577 the Crown ordered the confiscation of all the proto-ethnographical writings issued since the middle of the century.70

Although by this time he was retired, Zorita was probably informed about the reissue of the 1577 questionnaire in 1584 and decided to send his Relaciones to the Council of the Indies a year later in order to make his voice heard in a still open enterprise. In the turbulent context described above, it was hoped that the erudite and well-informed intervention on the part of a retired jurist such as Zorita, whose experience and professional trajectory were unparalleled, might encourage a change in the official criteria restricting research on Indian customs and antiquities, and reverse the current homogenizing trend in the legislation unfolding in the Indies. At least that was the aim of the elderly, yet still combative Zorita.

Having retired in 1567 and, therefore, not having direct access to the royal instructions issued after this point in time, Zorita probably had to go back to the cédula of 1553 in order to formulate his response to the kind of questions that the Council of Indies was (still) asking in 1584. While the solution presented in this erudite imbroglio is of little relevance to the purpose of this article, what I nevertheless find particularly interesting about the questionnaires elaborated by the jurists of the Spanish Monarchy between 1553 and 1584 and in some of the responses written by royal officers is the awareness of the complexity involved in the legal translation processes between Europe and America. From a legal historical perspective, the information about territories and peoples Ovando and López de Velasco obtained from 1569 to 1584 (preceded by less determined initiatives, such as the cédula of 1553) should be conceived in terms of general and essential information of fundamental importance to legislative processes as a whole and, more specifically, for the complex processes of legal translation.71 The translation encouraged by Castilian jurists and bureaucrats in the second half of the 16th century represents, in fact, one of the most complicated and intense attempts to date.

A general overview of the cédulas, questionnaires, and reports elaborated in the period between 1553–1584 shows that it was precisely a deep methodological awareness of the information needed in the legislation and legal translation processes that motivated their elaboration during | a critical moment in the Spanish rule over the Indies. Given that previous legal frameworks were connected to the violence and brutality inflicted upon the fragile body of Indian societies, thus represented one of the more important causes of the dramatic diminution of the former population,72 Ovando, and other supporters of geographical and proto-ethnographical inquiries, pointed to the need for understanding the realities of these almost completely unknown and mysterious lands and peoples before any new attempts to come up with laws were made. A better administration of the Indies as well as a convenient and stable legal framework would only be possible in the overseas territories of the Spanish Monarchy if a wide cultural and geographical assessment of the New World were officially undertaken. However, lacking its own legal criteria, America would remain a »poorly understood continent,« and full of »blind,« misinformed jurists73 who will continue to alternatively support the claims of conquerors-encomenderos as well as those of individuals presenting themselves as protectors of the Indians. As a result, inappropriate legislation (e.g. not taking into consideration the conditions of the lands and the needs of the people to which this legislation is addressed) would still be created, dispatched, proven to be counterproductive, criticized, and then abolished – just as it had been the case during the first seven decades of Spanish presence in America. In this period, knowledge and information were considered the means enabling Spanish jurists and bureaucrats to escape the vicious circle of ill-informed legislation. In doing so, they also hoped to avoid the imminent extermination to which the American native population seemed condemned during the first period of Spanish colonization.

It is important, therefore, for the history of legal translation to focus on the complexity of the research ordered by the cédulas and questionnaires of the period between 1553–1584 as well as on the interrelationship existing between the different topics that interested the Spanish Crown at this time. Starting from the still rudimentary inquiry ordered by the cédula of 1553, we can see that after a very precise and somewhat abrupt initial question about the quantity of tributes payed by Indians »at the time of their heathendom« (chapter 1), the following chapters of the questionnaire focused on the social and legal order existing in pre-Hispanic times. The authors of the cédula wanted – more concretely – to have basic information about the different kind of lords (universal and local) to whom tributes were given the means by which they acquired lordship, as well as the power and jurisdiction that these lords exercised over their subjects before and after the conquest.

The Council of Indies was interested not only in pre-Hispanic lords, but also in the traditional forms of owning and cultivating the land. In order to determine the tributes, it was necessary to know whether those individuals cultivating the land also owned it or, on the contrary, whether they were only solariegos living on the lands belonging to their lords and were, therefore, obliged to pay them tributes and were subject to their jurisdiction. Obtaining this basic social and economic information was, in fact, a prerequisite for understanding the indigenous fiscal system and calculating the amount of tributes to be paid. Additionally, cultural topics such as the ideas about honor and social acknowledgment in the pre-Hispanic era were taken into account by the jurists of the Council. They wanted to know, for example, if tributes were paid as a form of compensation for protection, renting land, or, if they were indeed symbolic in nature, i.e. a kind of recognition of a lord’s preeminence. The magistrates asked for this information in order to clarify whether Indians societies were organized according to the European-Christian patterns characterizing a three-estate system74 or whether »tributes were also paid by merchants or other kind of people.«75 |

The research and assessment concerning tributes ordered by the Spanish Monarchy in 1553 included, as I have shown, the basic social and cultural questions, which were considered as key requisites for understanding what – at least for the case of the Nahua region – was a very complex and stratified system of taxation. This system was derived from social structures and conceptions about honor neither coincident nor always compatible with Western ideas and institutions.76 Further cédulas and questionnaires elaborated by the jurists of the Council of the Indies, chroniclers, and cosmographers followed this line of research and made it even more complex. A close reading of the 50 chapter questionnaire, written by López de Velasco and dispatched to Spanish authorities in the Americas in 1577 and 1584,77 reveals the consolidation of a dynamic accumulation of knowledge; one considered indispensable for supporting the ongoing legal translation processes that took place between Castile and the Indies.

Significantly entitled, »Instructions about the reports that had to be done for the description of the Indies, ordered by His Majesty to promote their good government and ennoblement,« López de Velasco’s questionnaire went deeper than previous social and cultural research endeavors and widen the field of analysis to include cultural history, items related to navigation (relevant to towns located close to oceans and rivers), and landscape. Scholars, such as Mundy, had privileged the properly geographical questions addressed to royal officers and tended to consider López de Velasco’s questionnaires to be elements of a vast proto-scientific program – one essential to the mapping of the Indies.78 However, I think cartography only played a secondary and instrumental role in what was primarily a legally-oriented endeavor. The questions about tributes, social order, and political hierarchy in heathen times already asked in the cédula of 1553 were repeated in López de Velasco’s questionnaires.79 Furthermore, almost all of the geographical information the officers and clergymen were asked to compile and communicate can be related to the economic and juridical interests of the Crown. In this regard, numerous questions dealing with issues of weather, demography, topography, fauna and flora were clearly not driven by curiosity or erudition, but were asked in order to pave the way for further evaluations of lands, resources, and inhabitants.80 The internal logic of such a broad research seems to be determined by the guiding idea that by making the information about the water resources, mines, native and cultivated trees, wild and domestic animals (among many other resources) of every region of the Indies available to the jurists of the royal councils, it would be easier to build an adequate framework for fiscal policy (a never-ending headache for legislators), both with regards to the adjustment of previous tax assessments or when it came to imposing new ones coming directly from the peninsula, especially in cases where local authorities failed to reach agreements.

In conclusion, while contemporary scholars continue to emphasize the great importance of the chronicler-cosmographer Juan López de Velasco’s writings and his projects in relation to the history of science and mapping,81 their great significance for legal history should also be recognized. In fact, in his own response to the previous questionnaires, i.e. the hugeGeografía y descripción universal de las Indias, finished in 1574,82 López de Velasco justified his colossal research, compiling, | and ordering efforts about »Indian matters« by appealing to the importance of the information gathered for governmental action. He focused explicitly on the need to provide royal councils with independent and trustworthy information and pointed to the fact that this information would enable jurists and counselors to have access to an indispensable repository of knowledge, thereby breaking the previous dependency on the partial and contradictory accounts provided by American litigators. According to López de Velasco, only if equipped with a solid cultural, geographical, and legal background could royal councils undertake legislative processes in a more reliable and accurate way.83 Within the wide spectrum of what he considered »cosas necesarias en materia de gobernación,« his Geografía included geographical information (topographic and hydrographic elements, descriptions of the coasts, etc.) about every American region under the control of the Spanish Monarchy and a general account about the main characteristics of the New World: demographic, meteorological, botanical, zoological, geological, and ethnological issues were taken into account in the first chapters of his Geografía. The cosmographer paid special attention to the natives’ political, religious, and moral customs as well as described the system of rule and religious indoctrination put into practice by Spanish authorities into the Americas until 1574.

Zorita’s Perspectives on Legal Translation. Social and Cultural Knowledge, a Prerequisite to Building a Legal System

The two Relaciones that Zorita finished almost a decade after the redaction of the Geografía y descripción universal de las Indias opened up a completely new perspective on the way in which a juridical order could and had to be constructed in the Indies. While previous jurists and men of letters had demanded their subordinates to collect information and data about land resources, native social structures, and legal customs in order to know more about the context into which Castilian law and ius commune would have to be transferred, Zorita reversed previous trends and opted for the recovery of Nahua and Native American legal customs as the only way to ensure fairness and stability in the overseas territories incorporated to the Spanish Monarchy.

Zorita’s commitment to the indigenous legal systems is interesting not only for its pioneering character, but also for the lucid reflection about linguistic issues that the jurist made while justifying his personal engagement. Endowed with a good sense of intuition and a vast and erudite culture, Zorita was not a jurist confined to just technical issues. He was an intellectual able to contextualize and understand Nahua culture by contrasting it with the pagan cultures of Antiquity. Being quite familiar with the writings of the Apostles and Church Fathers, he attempted to show that the major social and political challenges connected with the co-existence of Christian, Pagan, and neophytes in early Christianity paralleled those that took place in early modern America.

In his Relaciones, Zorita quoted, for example, the well-known Letter to Pammachius (written in 395, and also called De optimo genere interpretandi), written by the Latin Father Jerome of Stridonius in order to explain and justify the methodology applied to his translations from Greek to Latin, where he constantly advocated for rendering »not word for word, but sense for sense.«84 Appealing to the authority of Jerome, Zorita attached great importance to the linguistic abilities needed to | understand the sense of Nahua speeches concerning ethics, worldview, and customs as well as to the capacity of appreciating their beauty:

Quando alguna vez yva algun señor ynferior o algun principal a visitar al señor supremo o a lo consolar de algu[n] trabajo que le avia susçedido le hazia un rrazonamiento que contiene buenos avisos y en su lengua paresçe y suena mejor que no traduzido en otra porque como el glorioso sanct g[e]r[oni]mo dize en una epistola que escrivio a pammachio que se intitula de optimo genere interpretandi que comiença paulus apostolus cada lengua tiene su propia y particular manera de hablar y lo que se escrive en una lengua no suena tambien como en ella si en otra se traduze (…).85

From a philosophical and linguistic point of view, Zorita’s refutation of the fallacious assimilation between the »barbarian« and the »uncivilized« also deserves thorough analysis, especially since he based his rejection upon an interesting etymological research of the word »barbarian.«86 According to Zorita, the term was created by Greeks and Romans to refer to »peoples of different speech« or »custom.« Nevertheless, for philosophers and historians of the Antiquity, the adjective »barbarian« did not imply any kind of negative connotations, which stands in stark contrast to the early modern period, where the »barbarian« was unduly equated with the »uncivilized,« lacking in manners and intelligence.

Coming back again to the specifically juridical dimension of Zorita’s writings, it is important to mention that, on the one hand, he went further than previous jurists in his consideration of social and cultural knowledge as a prerequisite to building a legal system. From this perspective, he focused on the principles of social organization and cultural values of the Nahua people, and, by making use of writings previously elaborated by missionary friars, he was able to provide extensive accounts regarding numerous topics related to indigenous history, worldview, and traditional patterns of interaction – all of which were identified as elements to be taken into account in the legislative process. On the other hand, Zorita stood out among the first Spanish jurists (along with Polo de Ondegardo in the Viceroyalty of Peru87) advocating the restoration of the Indian fueros (customary laws and privileges) as the only way to avoid what, at this period in time, was perceived as the imminent annihilation of Native American peoples. The restoration of the laws that, according to Zorita, had allowed the Indians to survive and proliferate for centuries clearly implied the need to carry out exhaustive inquiries of the native legal sources and find suitable methods for translating them. Since Zorita dealt specifically with the complexities of intercultural legal translation in the early modern period, his reflections are very important for the history of legal translation.

Zorita’s writings can be perceived, therefore, as the critical culmination of the official tendency to the rise in interest and attention paid to pre-Hispanic regulation of tributes and other elements of policy. On the one hand, he took royal instructions to their logical extreme, thereby satisfying the royal will to have an exhaustive account of the fiscal policy in force until the Spanish conquest. On the other, Zorita indeed used the information collected to undermine the juridical homogenizing perspective predominant in the legislation of | his time and which would have continued to prevail among the Spanish jurists dealing with asuntos de Indias. In this way, while the cédula of 1553 and later Ovando, López de Velasco, and Solórzano only wanted to find out more about Indian societies and their cultural values in order to better understand the context into which Castilian law and the general principles and provisions of the ius commune had to be translated – thereby paying, generally speaking, little attention to an undervalued indigenous law,88 Zorita used the above-mentioned cédula to subvert the previous approaches and propose a very different means for constructing a harmonic fiscal and political system in the New World: the restoration of an idealized past, to which he always referred with words of praise.89

As an example of the singularity of Zorita’s reasoning, it is important to mention that in his extremely tardy response to the cédula of 1553, he dared to alter the order of the questions addressed to the governors, judges, and clergymen. Following criterions more conducive to demonstrating the results of his rigorous and more comprehensive research focus (not so far removed from the order contemporary scholars now consider logical when speaking about the social and economic organization of a certain society) than the almost purely economic ones used by the jurists of the Crown, Zorita began his account by asking the most basic questions: the ones related to the political ideas and cultural values that, as the core beliefs of rulers and ruled in pre-Hispanic Anahuac, were taken as principles of social organization, division of work, and distribution of land among the Nahuas.

As I already mentioned, the Council of the Indies was primarily interested in having a brief account of the tributes the Indians paid under Moctezuma’s domination (already converted into Spanish pesos de oro). This petition was stipulated first in a cédula written primarily with the convenience of future readers of the reports sent from the Indies in mind. Zorita decided to ignore these fiscal priorities and to order the results of his research according to his own outline. In this way, while other responses to the cédula strictly adhered to the instructions and order of topics set out by the Council of the Indies,90 Zorita decided to first clarify the most basic social questions. At the beginning of his Breve y sumaria relación, he showed how indigenous societies were structured and which philosophical and religious ideas were important for grasping their conceptions of honor and social acknowledgement. |

Zorita was not very explicit about the reasons motivating the particular structure of his account, e.g. why he first dealt with »the ninth« chapter of the questionnaire. In the letter he addressed to the members of the Council of the Indies, meant as an introduction to his Breve y sumaria relación, he briefly stated that he had used his own notes and information taken from Franciscan friars (Toribio Motolinía, Francisco de las Navas, and Andrés de Olmos91) and »wrote down in my notebooks the material relating to the contents of the royal cedula, ordering all as well as I could.«92 Speaking vaguely of the necessity for re-ordering the questions of the cédula, he simply stated that he would »set down and comment on the articles individually, but not in the order in which they appear in the cedula.« The precise and quantitative answer to the questions about tributes was, therefore, postponed. Instead of uncritically satisfying the will of the jurists on the Council of the Indies, Zorita decided to put the cart before the horse: by first identifying the kind of lords that existed in pre-Hispanic Mexico, and second by explaining the power and jurisdiction they had exercised both before and after the Spanish conquest.

The order Zorita came up with in his Breve y sumaria relación and his alteration of the royal instructions of 1553 invite us to reflect on the complex implications of legal translation processes. This Spanish jurist from the early modern period seems to have been aware of most of the cultural, economic, and social elements that have to be taken into account in complex processes of legal translation and of the interdependence of all these components. Consequently, before making this hasty monetary assessment of tributes required by the jurists of the Council of the Indies, Zorita decided to provide them with an accurate report of the basic Nahua concepts, ideas, and values related to honor, authority, family, religious zeal, labor, justice, consolation, purification, etc. He wrote a kind of introduction to Nahua ethics and worldview – rather unusual for a juridical account – using, for example, long passages from the compilation of Huehuetlahtolli (»Speeches of the Ancients«) written by the Franciscan friar Andrés de Olmos around 1547.93

Zorita also provided detailed descriptions of the conditions under which the average Indian lived and worked: not possessing anything but »a very sorry mantle with which he covers himself, a sleeping mat, a stone to grind maize for his daily bread, and a few chickens« – a »fortune« valued at under 10 pesos.94 From his perspective, fair and stable95 tribute assessments would only be possible if the judges in charge of elaborating them visited Indian towns and villages on a regular basis and interacted with the natives in order to accurately assess the specific living conditions of potential tax payers and the resources produced in the regions were the assessments would apply. Instead of paying attention to these essential elements, the judge-legislators of the Audience of Mexico appear to have been somewhat lazy and indifferent in their approach, using outdated and distorted accounts as well as appealing to »subtleties and speculative | reasons.«96 Challenging the work habits of his colleagues, Zorita pointed to the fact that the diversity between the Old and New World was so great that even such an apparently unimportant issue as how one dressed had to be taken into account in tax assessments. This was, indeed, one of the elements that legislators have to consider if they wanted to reduce the mortality caused by forcing more or less naked men to work in the rain and the low temperatures of daybreak and late afternoon.97

Inapplicability of Royal Legislation for the Indies as a Result of a General »Misunderstanding«

Further reading of the Breve y sumaria relación makes it clear that Zorita used the cédula of 1553 as a pretext to speak about a set of political and social matters that, according to him, had to be taken into account every time a tax assessment was made in the Indies.98 Indeed, Zorita considered the general lack of social and cultural knowledge about American peoples to be the single most important cause (more important even than the greed and lack of commiseration of some settlers and royal officers) of the failure of legal reforms implemented by the Spanish Crown since the beginning of the 16th century in order to translate to the New World the legal framework of Castilian encomiendas.99

Ignoring, for example, the resources that were produced in every American region and overestimating the working capacities of a decimated and miserable population, the Spanish Crown and their officers were for many decades insistent on making the Indians pay tribute in ways and amounts that were unintelligible or impossible for them to afford. As a result of the brutal homogenizing legislative trends already mentioned, natives had paid and continued to pay a monetary tribute – a petition that was itself, according to Zorita, an »injury« to contributors not familiar with currency and reduced to utter despair in the crazy attempt to obtain reales so they could pay.100

As an example of what could even be considered an act of conscious resistance against the logic of homogenization that inspired royal legislation on tributes and the cédula he allegedly responded to, it is important to mention that Zorita was extremely brief, ambiguous, and evasive when, close to the end of his Breve relación, he decided to answer the question about the amount of taxes in the pre-Hispanic era – the issue the jurists of the Council of the Indies were most interested in. Zorita made vague reference to tributes always paid in raw materials commonly found in the regions were they were demanded, recommended the re-instauration of such a »harmonic« and »well-apportioned« fiscal criterion, and explicitly refused to calculate the value of local tributes in Spanish pesos de oro. His convictions on the matter make it clear that he considered such an operation to be an illegitimate close translation of a Castilian-shaped fiscal criteria. In fact, he thought that it was both impossible and unfair to make a monetary or value estimation of the raw materials that | Indians could easily find and stock up on prior to the conquest.101

Zorita’s statements against quantitative assessments are only a small part of his critical evaluation of the fiscal system implemented in the Indies. Not only gold and money were among the senseless petitions of Spanish authorities and encomenderos, but also wheat and other kinds of grain that Spaniards preferred to native maize. Zorita considered these kinds of petitions impractical and contrary to the customs of the contributors. He even referred to them as excessive and almost tyrannical »burdens,« which, from a legal point of view, were real »injuries« or »grievances« (»agravios« in Spanish) caused to Indians by negligent legislators.102

While avoiding talk of systematic oppression, Zorita nevertheless considered the fiscal policies implemented by colonial authorities in the recent decades to be clearly the result of not only the widespread greed and corruption, but also linked to a problem of misunderstanding. The term »misunderstanding« and expressions such as »it has not been understood« and »need to be understood« occur repeatedly in Breve y sumaria relación, where Zorita seems to be fighting, above all, to make the pre-Hispanic legal system comprehensible to his colleagues in Castile. Much like the misunderstandings involving the objects of tribute (gold, money, wheat, and Castilian grains), Zorita was convinced that the Spanish jurists trying to translate certain Castilian laws and institutional frameworks to the Indies were, above all, misinformed and disoriented.

Numerous misunderstandings had occurred, for example, within the framework of personal services that Spaniards required from the Indians by appealing to their existence as customary practices in the pre-Hispanic era. Scholars dealing with native American social structures and economic institutions prior to the conquest had shown that under the rule of native lords, commoners were obliged to work in maize fields, supply the houses of their lord with water, food, and wood, as well as work on the building projects.103 Spanish encomenderos and authorities directly profited from the ancient customs by appropriating them to make the Indians work long, exhausting days, as well as to carry heavy merchandises and equipment on long and dangerous journeys that brought them far away from their homes. Such workdays for the Indians were usually accompanied by undernourishment and having to sleep in open fields; such conditions were primarily responsible for the high mortality among Nahua population, especially during the early years of Spanish domination, when thousands of Indians died while working on the building projects undertaken in the ancient Tenochtitlan, working in mines,104 or traveling to extremely hot regions like Tehuantepec, where Cortés had intended to launch an expedition for the further discovery and conquest of still unknown territories across the Pacific Ocean.105

Zorita reflected on this problem responding to chapter 10 of the cédula-questionnaire of 1553. He did not consider personal service itself to be the cause of the annihilation of the Indians, but rather | the unusual and cruel conditions under which they were forced to pay tribute in the form of labor. Translation (not in the legal sense referred to earlier, but in its primary linguistic meaning) plays here an important role, because Zorita considered abusive personal services to be the result of a translation trap, that is to say, the consequence of a simplistic and intentional identification between the Nahua and Spanish concepts of personal service.106 The jurist reported that similar intentional misunderstandings and mistakes were made in the translation of other Nahua concepts and in the description of the pre-Hispanic institutions and social order.107

Contrary to the erudite writing style of other jurists,108 Zorita tended to clarify theoretical fallacies, hasty generalizations, and equivalences by appealing to the vast experience he had acquired in his travels in Northern, Southern, and Central America.109 Together with Las Casas,110 another experienced polemist, he fought against the proliferation of amphibology111 in the legal reasoning and argumentation of slave traders and rejected the inappropriate equation, as some early conquerors were quick to do, between the Western concept and practice of slavery and Native American concepts (naboría) referring to forms of servitude. Focusing more on Nahua legal vocabulary, Zorita made a similar denunciation of the intentionally false translation of the Nahua concept »huehuetlatlacalli,«112 unduly equated with the Castilian word esclavo. As Zorita explained in his Relación de la Nueva España, the legal condition of domestic servants in the pre-Hispanic era was much better than the one attributed to slaves by Castilian law and ius commune: Nahua servants had their own assets, they could be sold only in very rare cases, and their labor could be substituted for by relatives or friends. Some of them were even in charge of a household and had children who were born free.113 Consequently, their condition or status was not comparable to that of Castilian or European slaves.

The cases of personal service, slavery, and kinds of tributes and tributaries are but a few examples114 of the confusion prevalent among Spanish jurists while legislating with almost complete ignorance and disregard for native customs – a legislative trend that disrupted indigenous communities to the point of placing them into a state of extreme vulnerability. According to Zorita, the destruction of native traditions and subsequent misunderstandings of the fanciful and changing conditions of domination imposed by encomenderos and royal officers led Indians to be vicious and to constantly litigate between them. Principals | interviewed by the jurist showed an increasing desperation vis-à-vis a judicial system that encouraged bad habits,115 social disorder, and ruined them via expensive legal procedures that they did not even understand.116 The Indian opinions that Zorita reported are extremely representative of the mutual lack of understanding prevailing in the processes of legal translation between Castile and America that occurred without paying attention to precedent laws and customs:

Once I asked an Indian principal of Mexico City why the Indians now were so prone to litigation and evil ways, and he said to me: ›Because you don’t understand us, and we don’t understand you and don’t know what you want. You have deprived us of our good order and system of government; that is why there is such great confusion and disorder. The Indians have thrown themselves into litigation because you egged them on to it, and they follow your lead.‹117

This seems, perhaps, somewhat paradoxical considering Zorita was himself a judge and worked for 10 years in one of the most important Spanish courts of the New World. However, his evaluation of the changes that the creation of the Audience of Mexico, the elaboration of many laws supposedly designed to protect the natives, and the translation of the municipal structure of governance that was characteristic in Castile (were corregidores, alcaldes mayores, alguaciles, and other figures had different judiciary and administrative functions)118 brought to the daily life of the Indians was very critical. For Zorita, even if carried out according to fair and pious motivations, these legal changes had only contributed to the growth of a litigation culture unknown in the pre-Hispanic era119 and multiplied the number of agents that considered themselves authorized to »steal« from the poor commoners. However, despite their considerable number, they were unable to provide the land even a little of the peace, harmony, and love that had prevailed under the simple politic and juridical structures presided over by native lords.120 Zorita evaluated every one of the legal innovations mentioned above not against the Castilian criteria, which seemingly blinded his colleagues, but according to the specific needs of the Indies and their natives.121 His pessimism regarding the legal and political innovations introduced or tolerated by the Spaniards in Mexico reached such a point that he considered the eradication of the legal confusion and disorder derived from them to be basically impossible, even if a return to an idealized status quo of the pre-Hispanic system of rule, tribute, and land ownership became the normative goal to which further legal changes should aspire.

In the Andean regions, we find a similar perspective in the writings of Polo de Ondegardo. For Polo, royal officers had destroyed a well-ordered and accepted legal system; they introduced countless laws and provisions into the former Inca Empire that were not in accordance with the customs and characteristics of the land as well as | arising from alien environments and worldviews that would take natives »more than one hundred years to understand.«122

Zorita’s Appeal to Focus on the Pre-Hispanic Legal Customs and Sources. A Pioneering Awareness of the Need and Challenges of Intercultural Legal Communication

If we come back again to the cédula of 1553, we notice that the jurists of the Council of the Indies also carefully identified the kind of sources that had to be taken into account by Spanish authorities in regions like Mexico when compiling the fiscal report demanded: ancient pictographic codices123 and a very restricted kind of witness – namely, old native noblemen under oath. The linguistic abilities of friars living in Indian communities and native translators were also very much appreciated given the nature of Nahua legal sources: competent interpreters were required to make the codices ›talk‹ and interview the native noblemen who knew best the content of pictures, which, in most cases, had been kept for centuries as part of the family heritage.

A two-stage process of translation-interpretation, conducted under the direction of the judges of the Audience and made possible thanks to the help of Franciscan and Dominican friars as well as other qualified interpreters, was, therefore, necessary to make the sources previously mentioned ›speak.‹ The first stage involved having the native elders explain the pictographic representations of the village hierarchy and clarify the images and symbols concerning the kind of goods that the lords expected as tributes, the quantity, and intervals in which the Indians paid these tributes prior to the Spanish conquest, etc. The second, almost simultaneous, stage involved interpreters translating the verbally transmitted codices and statements by native elders into Castilian.

The way in which the instructions of the cédula of 1553 were put into practice one year later by the viceroy, Luis de Velasco, and the judge of the Audience of Mexico, Antonio Rodríguez de Quesada,124 makes it clear that the native aristocracy, to which the elder Indians witnesses belonged, was unable to speak Castilian three decades after the conquest. Even if some of them had a basic knowledge of this foreign language, it was probably insufficient to provide a detailed account concerning such a specific, and, at the same time, such a general matter as the tributary system prior to the conquest. On the one hand, very specific vocabulary about the types of lords, tributes, as well as land ownership and use were required for this translation exercise. On the other, an entire social and economic order had to be represented or translated into Castilian. With the help of interpreters, Velasco and Rodríguez de Quesada interviewed six native noblemen from Tlatelolco and asked them to explain in detail an ancient pictographic codex containing information about the tributaries of Moctezuma. Despite the linguistic difficulties already described above, the inquiry concluded with a surprising level of consistency among those interviewed. It is difficult to explain how the six witnesses examined by the viceroy and the oidor agreed on every single detail of their statements.125 More likely, however, is that the Spanish officers did their part to obtain this unanimous result. Just as the jurists of the Council of the Indies wanted, Velasco and Rodríguez de Quesada made their principals give very detailed translations of the value of the tributes supposedly paid to Moctezuma until 1521 in pesos de oro. They did not forget, however, to quadruple their value, drawing attention to the fact that the prices of the products given as tribute had increased since the 1520s. Thus, within these parameters, they were able to calculate an exact value for the sum of the tributes paid to Moctezuma: 1.962.450 pesos de oro. |

As I mentioned before, Zorita’s more systematic and complex explanation refused to conform to the monetary logic embodied in the approach of the jurists of the Council. Without confronting them directly, he advocated a deeper and more frequent consultation of pictographic codices and native noblemen when assessing the tributes. Furthermore, he insisted on the fact that the examination of the pre-Hispanic legal sources was not only necessary to provide figures to be used by tax collectors, but also to render justice to the natives regarding a number of other issues.

In Zorita’s opinion, a serious and systematic effort to compile and interpret the pictographic codices of the Indians was the only way to arrive at a correct understanding of the political and economic system that had prevailed for centuries amongst the Nahuas. When it came to the division and the conditions of use regarding the lands conquered by the Spaniards, this interpretation was deemed necessary, especially given that the encomenderos and other usurpers had profited from the disorder caused by the hasty legal innovations implemented in order to destroy the harmonic system of calpulli.126

According to Zorita, the conquerors were not responsible for the core problems and calamities endured by the Indians, but rather the immoral advisors and pettifoggers who, by inciting the Indian commoners to revolt against their natural lords, hoped to take advantage of chaos and confusion, thereby profiting from the costs of the proceedings before the Audience. Giving credence to litigants instead of requesting the submission of codices reflecting the former and legitimate division of the land and the assessments of tributes was at the core of the progressive destruction of the pre-Hispanic social structures. This kind of revolutionary dynamic implied for Zorita not only a transfer of property from one hand to another, but also a dangerous upheaval of the social, economic, and moral order prevailing among Nahua people for centuries. Bilingual Spaniards, mestizos, and mulattos troublemakers,127 having the support of the judges of the Audience or profiting from their useful ignorance and laziness, were identified as the main culprits in the destruction of former customs. This kind of legal and institutionally framed vandalism represented a great danger, especially when taking into account that the subversion of the previous state of affairs was being carried out neither having a solid substitute nor the slightest guarantee that the Castilian-shaped innovations would even take root in such an alien land. In this context, the understanding of ancient Nahua order and customs, made possible by the rescue, use, and interpretation of native legal sources, seemed to be the only way to stop such a destructive dynamic. Zorita, who had himself seen many codices and listened to a number of elder and prominent Indians while interpreting them, related to his colleagues in Spain in great detail the valuable information that could be found in these sources:

This principal [the calpullec or chinancallec, head or elder of a certain calpulli] is responsible for guarding and defending the calpulli lands. He has pictures on which are shown all the parcels, and the boundaries, and where and with whose fields the lots meet, and who cultivates what field, and what land each one has. The paintings also show which lands are vacant, and which have been given to Spaniards, and by and to whom and when they were given. The Indians continually alter these pictures according to the changes worked by time, and they understand perfectly what these pictures show (…). One must understand the concord and unity that once prevailed in these calpulli if one | would treat them justly and put an end to the confusion that now prevails in almost all of them.128

Zorita’s exhortation begging the members of the American Audiences and of the Council of the Indies to pay attention to and respect the pre-Hispanic legal customs and sources (just as it was the case in the numerous republics incorporated to the Spanish monarchy during the 16th century) is innovative with respect to the awareness of the specific needs and challenges faced by well-intentioned and cautious jurists getting involved in complex processes of intercultural legal communication. The care Zorita took to synthesize previous enquiries into the institutions, such as the calpulli, and to improve the results of earlier writings on these topics has led contemporary researchers working on land tenure and political ideas in pre-Hispanic Mexico to still use the Breve y sumaria relación »as a point of departure«129 for their own work.

Nevertheless, as Zorita denounced in his Relaciones, the consultation of native sources regarding the division and property of the calpulli was not the rule, but more the exception. According to his experience in the Audiencia of Mexico, Zorita stated that the complaints of Indian noblemen, founded on the contents of the codices, were usually ignored, while their former vassals, guided by scheming »Spanish and mestizo allies, commenced suits against the lords, charging them with misgovernment, and were able to prove [in the Audiencia] whatever served their ends.«130 Running counter to the judicial criterion followed by most of his colleagues in the Audiencia de Mexico, Zorita also considered this kind of neglectful attitude towards the sources and witnesses as another of the »injuries« inflicted by judges on the Indians. In this case, the injury was even worst because the calpulle was not only an individual, but an important legal figure acting on behalf of the other members of the calpulli,131 a collective severely affected by judges lacking of knowledge and good will.