Abstract

The claim in translation studies that Chinese tends to have a preference for stronger or more exaggerated terms than does English has not been substantiated by any hard linguistic evidence. One system to approach such perceived differences in intensity is degree of intensity (DOI), which is an important device of fine-tuning taken by a speaker to express interpersonal judgments. However, it has not been systematically studied, in quantitative terms, for the Chinese language, nor has a contrastive study been conducted between English and Chinese. This study aims to adopt a corpus-based approach and investigate the phenomenon, using the Chinese translation of a politically volatile English autobiography by a Chinese migrant writer, Wild Swans (Chang 1991), as the domain of study, and comparing it with another translation of this kind and against two reference corpora of non-translated texts (FLOB and LCMC). The findings of the research suggest that Chinese indeed prefers more and higher degrees of intensity, but they also show that translator’s choice-making plays an important role in the translation of degree of intensity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

It is often claimed amongst Chinese translators and interpreters that Chinese has a stylistic preference for more strident and rhetorically stronger terms and expressions (cf. Ouyang 2013); for example, the word “hěn” (very) is often added in Chinese translations without a “very” in the English source text. However, despite the popularity of such hypothesis, no systematic comparison has been conducted. This creates a dilemma in translation studies between English and Chinese: meaningful translation shifts in intensity introduced by the translator(s), sometimes with ideological consequences, are often overlooked by others merely as typological, or poetological (Lefevere 1992) preferences of the Chinese language.

This study sets out to test the hypothesis that there is a typological preference in Chinese for expressions of stronger intensity in comparison to English. A good indicator of this preference is considered to be the degree of intensity, which is an interpersonal system in mood adjunct within Systemic Functional Linguistics (SFL) (Halliday and Mattiessen 2014, 189). The degree of intensity, in English, is represented by adverbs that modify the intensity of an adjective, verb or adverb: for example, “slightly” indicates a low degree, and “completely” indicates a total degree. To conduct a contrastive study between English and Chinese from an SFL perspective, this study has compiled a list of lexical items for the DEGREE OF INTENSITY in Chinese, drawing on the work by Lü (1982/2002) on adverbs of degree. In investigating the commensurability of systems in English and in Chinese, this study sets out to distinguish whether choices of the degree of intensity in a translation are influenced by typological differences or by translator’s ‘motivated’ choices (Butt 1988).

To enhance systematicity, this study adopts a corpus-based approach, supplemented with qualitative analysis of selected concordance lines. As expressions of intensity are predominantly adverbs, which, in English, are not subject to changes in tense, plurality or contraction, they are considered a suitable object for a corpus-based study. Using a concordance programme called SysConc (Wu 2000), we set out to demonstrate how the degree of intensity can be usefully explored across languages using a corpus-based approach. This may provide a perspective on how grammatical features can be explored in corpus-based studies to complement its traditional strength in studying lexis (Hunston 2013).

The main domain of study is the English source text (ST) of Wild Swans (Chang 1991/2003), which is the most successful English autobiography written by a Chinese migrant writer in the UK, and its Chinese target text (TT) (Chang 1992/2011) published in Taiwan. They will then be compared to a translation of a similar kind to reveal potentially generalisable patterns: another best-selling English-language autobiography by a Chinese migrant writer in Australia, Mao’s Last Dancer (Li 2003/2009), and its Chinese translation published in Taiwan (Li 2009). Both English STs are highly valued texts for being best-selling and award-winning (Chang 2018; Penguin Australia 2017) in the English-speaking countries; not only are both autobiographies in genre, but they also share a unique feature of being authored by non-native speakers of English despite the acknowledgements of critical input from numerous native speakers in both instances (Chang 1991/2003; Li 2003/2009), including the polishing of the English language. The two works and their translations also form a unique translation phenomenon where the source texts are translated into the authors’ native language, with assistance from the ST authors. This unique phenomenon has, to date, received little scholarly attention. The ideological volatility of the texts demands systematic exploration of the shifts in the interpersonal meaning through choices in the systems of the degree of intensity. To move beyond genre-specificity, idiosyncrasy and potentially translation-inherent features towards more generalisable comparisons between English and Chinese, the ST and the TT of Wild Swans will be respectively compared to two balanced and representative reference corpora of non-translated English (FLOB Corpus) and non-translated Chinese (LCMC Corpus); the latter two align perfectly with the initial publications of the ST and the TT of Wild Swans in terms of timing around 1991. These multi-layered comparisons may help determine whether a particular pattern in translation reveals a translator’s choices or is merely influenced by typological preferences of the Chinese language.

To achieve the overall objective, these research questions have been raised as guidance:

-

1.

How are degrees of intensity expressed in English and in Chinese? Are there even commensurable systems?

-

2.

What kind of shifts have occurred in the translation process in terms of instances, frequency, and degree? What are the semantic consequences?

-

3.

To what extent can the shifts be attributed to stylistic differences between English and Chinese? And to what extent can they be classified as motivated selections?

Despite the data focusing exclusively on English and Chinese, this study will hopefully be of interest to typologists and translation scholars working in other languages, as gradability is presumably a feature of various interpersonal systems in many other languages.

Degree of intensity

The DEGREE OF INTENSITY is an interpersonal system that situates within Halliday and Matthiessen’s concept of MODAL ADJUNCTS, which are types of modal assessments that extend beyond the ‘core’ systems of polarity and modality within the interpersonal metafunction in English. Modal adjuncts include the mood adjunct and comment adjunct. A mood adjunct serves to modify the mood element, which includes “Subject + Polarity + Finiteness” in English (Halliday and Mattiessen 2014) and “Subject + Polarity + Predicator” in Chinese (Halliday and Halliday and McDonald 2004), and mood adjunct is closely associated with the meanings enacted by the mood system: modality, temporality, and intensity.

According to Halliday and Mattiessen (2014), 188), adjuncts of intensity fall into two categories: the first type relates to the degree, and the second type relates to expectation, which can be “limiting” or “exceeding” what is expected. Although counter-expectancy (Heine, Heine et al. 1991; Traugott 1999; F. Wu 2004; Yuan 2008) and subjectivity (Lyons 1982; Shen 2001) are also interesting areas of research, we decided not to consider intensity of counter-expectancy within the scope of this paper, due to a similar lack of commensurable descriptions between English and Chinese from an SFL perspective.

For English, Halliday and Mattiessen (2014), 189) divide the mood adjuncts of intensity into three degrees: (1) total, such as “totally”; (2) high, such as “quite”; (3) low, such as “scarcely”. The three degrees are substantiated with a list of lexical items.

In Chinese Linguistics, there has been no description of the degree of intensity explicitly from an SFL perspective, although there are similar studies under the name of “adverbs of degree” (程度副词chéngdù fùcí) (Lü 1982/2002, 146–149; Zhu 1982, 196–197; Hu 1962, 290; Fang 2014). However, most scholars have not proposed a clearly gradable paradigm of intensity, and gradable intensity is often mixed with non-gradable intensity such as those of counter-expectancy. Lü (1982/2002) has identified adverbs of three degrees: low degree - including adverbs of high intensity in negation, high degree, and total degree, and discussed quantifiers that may express an intensity beyond the total degree in a metaphorical sense, such as 十二分 (shí èr fēn: 12 out of 10). He lists systems of gradability including adverbs, quantifiers, exclamation, simile, and lexical repetition.

This study focuses exclusively on the inscribed forms of gradable intensity. This means excluding English adverbs that are non-gradable such as “actually” and “merely”, expressions of intensity that are metaphorical such as “dead” in “It’s dead silence”, or instances where a degree of intensity is used in a non-gradable sense: for example, “quite” in “quite motionless” (Biber et al. 1999, 556). Likewise, metaphorical expressions in Chinese such as quantifiers, simile and lexical repetitions are excluded.

This exclusivity inevitably does not capture the full picture of gradability, which can take more implicit or emotionally loaded forms. For instance, Martin & White (2005, 141) discuss ‘force: intensification’ amongst other systems of graduation in their appraisal framework, which can be used for detailed qualitative studies of English intensification of both the inscribed and the invoked types. Nevertheless, for a better understanding of typological differences between English and Chinese, the DEGREE OF INTENSITY is considered a good starting point for its significance as the archetypal expression of intensity and its clear suitability for corpus-based methodologies and generalisability.

Although this study originates from the system of MOOD ADJUNCT, all instances of the DEGREE OF INTENSITY would be counted, regardless of whether or not they modify a mood element. Admittedly, those that form part of the mood element are more consequential grammatically than the adverbs of degree in a nominal group: for example,

-

(1)

Modifying the mood element: this excuse is totally unacceptable.

-

(2)

Within a nominal group: this is a totally unacceptable excuse.

The first “totally” may be grammatically more significant than the same adverb in the second example, as the first one directly alters the negotiability of the proposition. However, as computational tools do not automatically recognise mood adjuncts, it would be cumbersome to manually delete all instances of non-mood-adjuncts when working with large body of texts, even though the degree of intensity that are situated in the mood element are expected to be the majority. Since all instances of the DEGREE OF INTENSITY should be considered meaningful, the results in this paper have included degree of intensity both as mood adjuncts and other elements.

The lexical realisation of the DEGREE OF INTENSITY in English

This paper proposes an elaborated list of the DEGREE OF INTENSITY in English, with a few additional adverbs taken from Biber et al. (1999, 556) in their discussion of the ‘adverbs of degree’, and Martin & White (2005, 141-142) in their discussion of ‘force: intensification: isolating & maximization’, as shown in Table 1 below:

The lexical realisation of the DEGREE OF INTENSITY in Chinese

This study adopts Lü’s list of the adverbs of intensity in Chinese, as shown in Table 2, but excludes systems such as quantifiers and a small number of archaic adverbs such as 盎àng. In addition, a decision was made to add the appropriate Chinese translations of a number of English items in Table 1 that are not included on Lü’s list despite having natural equivalences in Chinese, based on Lu Gusun’s English-Chinese Dictionary (2007).

A notable typological difference between English and Chinese is the location of the degree of intensity, which is more flexible in English. There are four possible locations to place adverbs of intensity in English (Halliday and Mattiessen 2014, 187): 1) before the Subject (thematic), 2) before the Finite verbal operator (neutral), 3) after the Finite verbal operator (neutral), and 4) at the end of the clause (afterthought). In contrast, whilst Chinese adverbs are usually placed before the Predicator, there are some Chinese adverbs of intensity such as “lìhai” and “huāng” that have an obligatory position after the Predicator: i.e., 累得慌 (lèi de huāng: tired + high intensity). Nevertheless, the position of the degree of intensity does not affect results in this corpus-based study. Furthermore, similar to the handling of the English degree of intensity in corpus, concordance lines in Chinese are manually excluded in this study when the usage of a token of intensity is irrelevant to intensity and its gradability: for example, 大 dà as an adjective meaning big.

Data and methodology

Data selection

The ST and TT of Wild Swans (Chang 1991/2003) were converted from hard copies to machine-readable texts using optical character recognition (OCR). All copies were used strictly for private academic research under fair dealing. The machine-readable texts were then manually proofread to minimize any errors in the OCR. The ST and TT of Mao’s Last Dancer were collected through the same process, but only 17 out of the 33 chapters were selected to strike a balance between labour-intensity and representativeness.

To distinguish typological differences from translators’ choices, the ST and TT of Wild Swans will be compared respectively with the Freiburg–LOB Corpus of British English (FLOB) (Mair 1999), and the Lancaster Corpus of Mandarin Chinese (LCMC) (McEnery and Xiao 2004); both are a million-word corpus that were designed to match the classic LOB Corpus (Leech and Johansson 1978), and LCMC was designed as the Chinese comparable corpus for FLOB so that contrastive studies can be made between English and Chinese. The reason for the choice of reference corpora are four-fold. Firstly, FLOB and LCMC are comparable corpora, and both were carefully designed to be balanced with systematic collections of sampling (Hundt, Sand and Siemund 1999; McEnery and Xiao 2004) to ensure representativeness of the published British English and Mandarin ChineseFootnote 1; and LCMC is the most balanced and representative Chinese corpus that is publicly available. Secondly, both corpora are collections of texts either in 1991 or within ±2 years of 1991, and the ST and TT of Wild Swans were respectively published in 1991 and 1992. Therefore, both corpora are time-appropriate as a reference. Thirdly, these corpora are either publicly available, or a free access can be requested. And lastly, their million-word sizesFootnote 2 guarantee valuable insight into the probabilistic grammar (Halliday 1991) of the DEGREE OF INTENSITY in English and Chinese. With these four reasons, FLOB and LCMC are considered the best possible reference corpora for the purpose of this study. Then, the Category-G of both FLOB and LCMC, which consist of mainly biography, are singled out as the reference sub-corpora to match Wild Swans in text type.

Details of the four texts are listed alongside the non-translated reference corpora in Table 3 below:

Data analysis

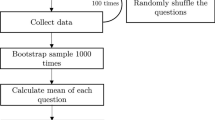

As shown in Fig. 1, the concordance programme SysConcFootnote 3 (Wu 2000) has been used to create the lists of features for the degree of intensity in English and Chinese based on Tables 1 and 2, so that instances that satisfy the selected features could be extracted simultaneously within a given body of text, and quantitative information generated.

As illustrated in the figure above, the features for English and Chinese listed in Tables 1 and 2 were represented as hierarchical lists in SysConc, with items of query for each feature listed as regular expressions. When a search was carried out on the ST and TT of Wild Swans, there were, as expected, high percentages of irrelevant concordance lines, in which the tokens either did not express gradable intensity or were not correctly identified, making it necessary for the query items in the lists to be revised.

A quick scan of the concordance lines showed three main types of issues. Firstly, although negation of the total and high degree of intensity would change or reverse the degree, this reversion had not been built in the raw features: for example, “completely” expresses total intensity, but “neg. + completely” expresses low intensity. This problem was solved by using a regular-expression construct from the manual of SysConc that would exclude negation before a high intensity: for example, the feature “(? <!(not\W|n’t\W|not been\W))completely” only searches for the positive “completely”, whilst “(? < =(not\W|n’t\W|not been\W))completely” only searches for “neg. + completely”. Secondly, some unintended words that contain a featured item came up unexpectedly: for example, “every” came up as “very” was featured; this issue was addressed by adding additional word boundary in the construct: “\bvery\b”. Thirdly, when a word had the semantic potential to express both a relevant meaning (degree of intensity) and irrelevant meanings, the raw features failed to distinguish them: for example, “fairly” as an expression of high intensity can also express the meaning of “without bias”; this problem was tackled by identifying the relevant and irrelevant collocations, and subsequently including/excluding those associations beforehand or afterwards, depending on whether it was inclusion or exclusion that would require less labour: for example, “(? <!(treated\s))\bfairly(?!(\streated|\sdistributed))” ensures that all concordance lines containing the word “fairly” expresses a degree of intensity by excluding any irrelevant associations with “treat” or “distribute” in Wild Swans-ST.

The revised features were tested and revised a number of times to keep the number of irrelevant concordance lines to a minimum. Although the methodology is reasonably straightforward, the process was unexpectedly time-consuming, as it could take hours to scroll down thousands of raw concordance lines whilst trying to identify patterns of collocations required to revise a particular feature item.

It was particularly labour-intensive for the development of Chinese features, as the percentage of irrelevant lines was high to start with. These problems were amplified when the same feature lists were tested on larger corpora like LCMC. As previously mentioned, relevant concordance lines were found either by including all relevant collocations, or excluding all irrelevant collocations, depending on which approach would be more efficient. For instance, it was decided that exclusion would be more efficient for the feature of low Chinese intensity “(一/有/有一)點” ([yì/yǒu/yǒu yì] diǎn: a bit), even so, more than 100 exclusions had to be specified in this case for LCMC, with more than 50 specifications both before and after the word “點diǎn” to rule out all irrelevant concordance lines. Further effort was required in revising the Chinese features for LCMC, as LCMC has been segmented for word boundaries, whereas the initial features built for Wild Swans-TT were built for texts without word boundaries; the revision of features was essentially a rewriting process. Nevertheless, the final featuresFootnote 4 have been built to work successfully with LCMC to reveal instances of the degree of intensity under investigation in this one-million-word corpus of simplified written Chinese, and should be applicable to other Chinese corpora with word boundaries without major revision.

When the feature lists were successfully built, SysConc could then generate quantitative results by searching for the instances of different degrees of intensity, as shown in Fig. 2.

Results were then compared between the ST and TT of Wild Swans, between Wild Swans and Mao’s Last Dancer, and between Wild Swans and the reference corpora.

Results and interpretations

Typological differences between English and Chinese through comparing FLOB and LCMC

As FLOB and LCMC are carefully designed as comparable corpora with each other, they provide a sound basis for contrastive studies of Chinese and English. A comparison of FLOB and LCMC (see Table 4) shows higher frequencies of the degree of intensity in non-translated Chinese than in non-translated English, particularly in the text type of biography and essay, with a stark contrast of 70.9 vs. 28.9 instances per 10,000 words respectively in LCMC-G and FLOB-G. In addition, Chinese overall shows higher percentages of total and high degrees than do the British counterparts, although Chinese appears to have slightly higher percentages of total intensity and British English of high intensity. In short, authentic Chinese written texts express considerably higher frequencies of intensity and slightly higher intensity than do British English texts, although the second trend may not apply to the text type of biography and essay.

Degree of intensity in wild swans

As shown in Table 5, the Chinese version of Wild Swans shows considerably more instances of the degree of intensity than does the English ST, with a 67.2% increase from 864 in the ST to 1445 in the TT. This also affects the frequency and distribution of the degree of intensity across the books, which is a latent pattern that can impact on the readers on the subliminal level: whereas the normalised frequency of the degree of intensity per 10,000 words is only 39.2 in the ST, it is 72.4 in the TT.

The intensity expressed in the TT is also of higher value: amongst the three degrees, total degree has increased considerably in both instances and percentages. As for high intensity, the large numbers of “hěn” (634 times) and “fēi-cháng” (89 times), both of which are equivalent of “very” (284 times), show the most dramatic quantitative difference between equivalents in translation. However, its semantic consequence is less significant than the increase of total intensity, such as “extremely”. Firstly, as Lü pointed out, “hěn” no longer strongly indicates high intensity in Chinese. Secondly, although by no means obligatory, it is common to translate the Finite “am” in “I am+adjective”, for example, in “I am happy” into hěn (very), as in “Wǒ hěn kāixīn” (literally: I very happy), as Chinese does not have a grammaticalised system of FINITENESS.Footnote 5 An alternative translation technique using the “是 … 的shì … de” structure, which avoids adding the high intensity, may be less frequently adopted. Even though the semantic consequence is not significant, a translator who abides by the principle of accuracy should avoid unnecessarily adding an intensity of high degree, as the accumulated effect of such patterns may create a TT that is more strident than the ST, as is this case, whether or not they were the translator’s conscious and deliberate choices. As mentioned, shifts in the total degree are more consequential, as they project the highest degree of interpersonal judgement, and are generally not obligatory. In this case, there is a dramatic increase of 80.5%, from 246 to 444, which, by percentage, is much higher than the increase of high intensity.

These patterns echo a previous finding (L. Li 2017) that Wild Swans-TT employs more and higher MODALITY, and open up the question whether the increases in higher intensity of interpersonal assessments are influenced by the abovementioned typological preferences in Chinese, making it necessary to compare these results with those in the other translation of Mao’s Last Dancer.

Comparison between wild swans and Mao’s last dancer

A comparison of Tables 5 and 6 show that the degree of intensity in the two English STs has a similar pattern of realization despite the fact that Wild Swans and Mao’s Last Dancer are British and Australian publications respectively, with a time gap of 12 years. As shown in the tables, the top four items of ‘total’ degree are the same in Wild Swans and Mao’s Last Dancer: “too/completely/totally/extremely”, albeit in different order; it is a similar case with the items in the category of ‘high’ and ‘low’ degree.

However, in comparison to Wild Swans, the English ST of Mao’s Last Dancer has slightly lower frequency of intensity: 38.2 per 10,000 words versus 39.2 in Wild Swans. Furthermore, Mao’s Last Dancer-ST expresses much higher intensity: 37.83% of total intensity in comparison with 28.51% in Wild Swans-ST; the percentage of low intensity in Mao’s Last Dancer is a mere 6.91%. Mao’s Last Dancer-ST clearly expresses stronger and more intense interpersonal assessments than does Wild Swans-ST.

There are also similarities and differences between the two Chinese translations. On the one hand, the two translations share overwhelming similarities in terms of the choices of the expressions in Chinese: the two TTs share identical top five expressions of high intensity: hěn/ fēicháng/ jīhū/ tèbié/ xiāngdāng, identical top three expressions of total intensity: tài/ jí/ wánquán, and the top four expressions of low intensity with a different order: shāo/ diǎn/ xiē/ hái & jīhū + neg. This suggests that translated Chinese texts potentially share a higher level of similarities in grammatical features with each other than with non-translated Chinese. In addition, both Mao’s Last Dancer-TT and Wild Swans-TT contain more instances of the DEGREE OF INTENSITY than do their respective STs, with 304 vs. 838 for the former and 863 vs. 1445 for the latter.

On the other hand, there is a more dramatic shift in Mao’s Last Dancer than Wild Swans taken in relative terms, with the former having a staggering 108.6 instances per 10,000 words, as compared to 72.4 in the latter. More importantly, whereas considerable shifts have occurred across the three degrees of intensity in the case of Wild Swans, those in the total degree are the most semantically consequential. In comparison, shifts in the case of Mao’s Last Dancer are concentrated on the strand of high intensity, with a dramatic 279% increase from 168 to 637. However, as is the case of Wild Swans, this is largely due to the addition of “hěn” and “fēicháng”, which is too common to be highly consequential in English-Chinese translation: there are 109 “very” in Mao’s Last Dancer-ST, but 514 “hěn” and 77 “fēi-cháng” in Mao’s Last Dancer-TT. If “very”, “hěn” (very) and “fēicháng” (very) are not considered, the shifts of total, high and low degree of intensity from Mao’s Last Dancer-ST to Mao’s Last Dancer -TT would respectively be 39, 47 and 27, which, compared to Wild Swans, can be considered as minor shifts. This shows that the translation of Mao’s Last Dancer can be considered as being more faithful than the translation of Wild Swans.

In short, the translation of the degree of intensity in Mao’s Last Dancer can be considered as being more faithful than that of Wild Swans; the TT of Wild Swans deviates more from the ST especially through shifts of the total intensity. Such a sharp contrast between the two comparable translations shows that shifts in Wild Swans cannot be dismissed as being merely random, or the results of typological preferences in Chinese. Nevertheless, similarities between the two translations indeed show influence by the typological preference in Chinese for more and higher degree of intensity in comparison to English, as revealed through the comparison of FLOB and LCMC in Section 4.1.

Comparisons between the two translations and non-translated Chinese

Figures 3 and 4 show the comparisons of the normalised frequencies of the degree of intensity and of the percentages of total intensity across corpora.

As shown in the figures, the comparison between FLOB and LCMC shows that Chinese overall expresses stronger intensity than do English texts, with higher frequency of the degree of intensity (48.8 in Chinese versus 33.6 in English per 10,000 words), and a higher percentage of intensity of total degree (29.8% in Chinese versus 26.1% in English. Therefore, increases in the instances of the degree of intensity, especially in the total degree in a Chinese translation, can be partially attributed to typological preferences in Chinese. This means that a preference for higher degree and frequency of intensity in the Chinese language relative to English have influenced both translators to express stronger intensity in the two translations than do the English source texts.

However, the figures also show that the frequencies of the degree of intensity and the percentage of total degree in Wild Swans-TT (left six) have exceeded not only those in the ST but also those in LCMC and the reference corpus of LCMC-G. Therefore, it becomes clear that the increase of the degree of intensity, especially that of total degree in the Chinese translation of Wild Swans, cannot be merely dismissed as typological differences between the two languages; rather, they reveal the translator’s choice to express stronger interpersonal judgements in the TT than in the ST. Such selections are further explicated when the translation of Wild Swans was compared to that of Mao’s Last Dancer; in the latter case, there is in fact a significant decrease in the percentage of total degree, with minor overall shifts in degree of intensity, except for the twice discussed issue of the addition of “hěn” in Chinese. The high frequencies of 很hěn (very) and 非常fēicháng (very) may bea feature of “translationese”: translated Chinese from English may deploys more 很hěn (very) and 非常fēicháng (very) than do non-translated Chinese due to the more restricted grammatical potential of the Chinese verb “是shì” in comparison to the English “be”.

On the other hand, whereas the higher frequencies of intensity deployed in the two STs than do non-translated English texts in FLOB may have encouraged the translators to express intensity more frequently simply due to the expectation of faithfulness to the source texts, the extent of this source text influence on the translations remains unclear: for instance, whereas Wild Swans-ST shows higher frequency of DOI than does Mao’s Last Dancer-ST, the two translations show the opposite trend. This suggests that typological differences and the translator’s choices have greater impact than the ST influence on the use of DOI in a translation.

Semantic and ideological consequences of the shifts in the degree of intensity in Wild Swans

This study has found that shifts in the degree of intensity in Wild Swans have the semantic consequence of creating a Chinese version that is of greater interpersonal intensity than is the English source text. Whereas the focus of this study is the typological differences and the corpus-based methodology, some qualitative analyses of concordance lines have been conducted, which found that shifts in the degree of intensity have resulted in changes in the representation and evaluation of characters, including a less negative representation of Mao Zedong in the Chinese translation.

Degree of intensity and the author-narrator’s family

Whereas a considerable overall increase of intensity of total degree from 246 to 444 – an 80% increase – has been found from the ST to the TT, this increase is found to be more dramatic when it couples with matters that concern the author-narrator personally. A total of 43 English concordance lines that contain both a token of total intensity and ‘I’ (or ‘me’) has been found in Wild Swans-ST. In contrast, a total of 87 such lines in Chinese (with a total intensity and ‘我’ wǒ: I/me) has been found. This suggests that the Chinese translation is a more personalised account than the English ST, and that the Chinese TT tends to express stronger interpersonal assessments than does the English ST toward matters that concern the author personally (cf. Li 2017; Li et al. 2019). For example:

Example 1 is extracted from a chapter in which the author was sent to work in the countryside alongside peasants during the Cultural Revolution. Having grown up in a privileged family in Chengdu city, she expressed frustration over the strenuous and unpleasant task of carrying a basket of animal manure on her back before emptying the content onto the field.

Example 1

DOI used | ||

|---|---|---|

ST | When I finally arrived at the field I saw the peasant women skilfully unloading by bending their waists sideways and tilting the baskets in such a way that the contents poured out. | n/a |

TT | 當我終於走到 那塊空地時, 我看到背糞的農婦們都十分靈巧地把腰斜著一扭 … | Total degree |

Back translation (BT) | When I finally arrived at that empty field, I saw all the manure-carrying peasant women extremely skillfully bending their waists … |

By turning up the degree to which the peasant women were considered skilful, the Chinese translation provides sharper contrast between the skilfulness of the peasants and the author’s clumsiness; this in turn conveys a stronger sense of self-mocking and projects stronger differentiation and incompatibility between the author and the peasants – a recurring theme in the book. This serves to sharpen the author/narrator’s out-of-place feeling and personal resentments toward being sent to work with the peasants in the countryside.

Example 2

DOI used | ||

|---|---|---|

ST | My father also found it difficult to strike up a close relationship with Jin-ming, but he was very close to me. | 1) n/a; 2) high degree |

TT | 我父親也很難接近京明, 但卻和我十分親密。 | 1) high degree; 2) total degree |

BT | My father also (found it) very difficult to get close to Jinming, but (he) was extremely close to me. |

Whereas the first addition of ‘很hěn’ is likely to be influenced by the previously mentioned typological difference, the second shift from ‘very’ to ‘十分shífēn’ (completely/extremely) is more noticeable, which cannot be plainly accounted for by any inherent linguistic difference. The Chinese translation suggests a closer tie between the author/narrator and her father. Many similar examples can be found in supporting the claim that the Chinese translation expresses higher degree of intensity toward matters that are personally related to the author and her family.

Another important difference between the ST and the TT is that total intensity tends to couple more with personal attributes of positive valence in the TT, such as happy, excited, relaxed, close/intimate, pleasantly surprised, and beautiful. The English total intensity is used overwhelmingly to couple with negative personal attributes, such as scared, sad, aggressive, dominated, horrified, and irritated; only two out of the 43 instances of total intensity are used to modify positive attributes. In comparison, 13 instances out of 87 instances of Chinese total intensity are found to modify a positive attribute. This suggests that the increase in the intensity concerning the author/narrator and her family does not have a particular ideological consistency: both the positive and negative attributes and states associated with ‘I’ have been enhanced in the Chinese translation.

Degree of intensity and Mao Zedong

Whereas the higher intensity of the Chinese translation is clearly reflected in the translation of lines that contain both a total degree and ‘I’, this overarching trend, supported quantitatively, does not apply to the translation of concordance lines that contain both a total degree and ‘Mao’. A number of translation shifts consistently show that the Chinese translation tones down the intensity in lines concerning Mao, which is a highly foregrounded pattern.

Examples 3-5

No. | Examples | DOI used |

|---|---|---|

3 | ST: Mao had said that ‘education must be thoroughly revolutionized.’ | total degree |

TT: 毛澤東說過 [教育要革命] | n/a | |

BT: Mao had said, ‘education must be revolutionized.’ | ||

4 | ST: Mao had accused schools and universities of having taken in too many children of the bourgeoisie. | total degree |

TT: 毛澤 東指責中學 、大學偏重資產階級子弟, | n/a | |

BT: Mao Zedong had accused schools and universities of having biases towards children of the bourgeoisie. | ||

5 | ST: We needed something to occupy ourselves, and the most important thing we could do, according to Mao, was to go to factories || to stir up rebellious actions against capitalist roaders. Upheaval was invading industry too slowly for Mao’s liking. | total degree |

TT: 那時我們沒事幹 , || 正好毛澤東又因為工廠文革開展不起來 || 而要年輕學生去「煽風點火」。 | n/a | |

BT: At that time, we had nothing to do, and it happened that Mao wanted young students to ‘fan the fire’ as the Cultural Revolution was not being carried out at the factories. |

The three tokens of strident total intensity contribute to an image of Mao as being aggressive and impatient in English. However, as it may be easier for Chinese readers to verify the source of information, Mao’s quotes in English had to be translated to his original wording, which, in the case of these examples, are in fact without any degree of total intensity, and therefore appear less strident than the English ST. The omission of these three instances of the English total degree in the Chinese translation suggests potential exaggeration in the English ST when presenting a translated quote of Mao in English to Western readers; and such exaggeration cannot be easily verified in English. This suggests that certain translation shifts may be considered as attempts to rectify the over-interpretation of Chinese history in the English ST.

In addition, although a few Chinese lines show the addition of a total intensity when there is no equivalence in the English source, the Chinese translation is nevertheless an understatement.

Example 6

DOI used | ||

|---|---|---|

ST | At the same time, Mao was sowing the seeds for his own deification, | n/a |

TT | 同時, 毛澤東也播下了對他個人絕對忠誠的種子, | total degree |

BT | At the same time, Mao had also sewn seeds of being absolutely loyal to him. |

Although the Chinese TT uses a total degree “絕對” (juéduì: absolutely), it may be argued that “being absolutely loyal to Mao” is an understatement of “deification of Mao”; the latter means treating Mao as a god (deity). “Deification” have occurred four times in the ST; however, it has been translated faithfully into “神化崇拜” (shénhuà chóngbài: deified worship) only twice. In Example 6, deification – treating Mao like a god – has been toned down in Chinese as “being absolutely loyal”, removing any religious connotation.

Whereas stronger interpersonal assessments have been expressed in Chinese toward matters that concern the author, the same cannot be said about matters that concern Mao. In many examples such as those above, the higher degrees of intensity to construe Mao as an aggressive and impatient dictator in English have been toned down or omitted, construing a less explicitly negative, and perhaps also a more balanced and proportionate image of him in the Chinese translation.

Degree of intensity and Madame Mao

Although both the ST and TT contain only two sections that contain both a degree of intensity and “Madame Mao”, or Jiang Qing, analysis of the four instances clearly show more negative evaluation of Madame Mao in the Chinese translation.

Example 7

DOI used | ||

|---|---|---|

ST | Mme. Mao said publicly, ‘There were merely several hundred thousand deaths. So what? Denouncing Deng Xiaoping concerns eight hundred million people.’ Even from Mme. Mao, this sounded too outrageous to be true, but it was officially relayed to us. | total degree |

TT | 毛夫人公然說:「唐山不過就死了幾十萬人嘛!有什麼了不起, 批判鄧小平才是關係八億人民的大事。」這話就是出自暴戾的江青之口也好像太暴戾過分了。 | |

BT | Mme. Mao said publicly, ‘weren’t there merely several hundred thousand deaths! So what? Denouncing Deng Xiaoping is the bigger matter that concerns eight hundred million people.’ This sentence seems too ruthless and outrageous even if coming from the ruthless Jiang Qing. |

In Example 7, whereas there is no shift in the intensity of total degree, the prosody in the textual environment of the total degree “too” expresses more negative evaluation of Madame Mao in Chinese. Not only is one negatively loaded English word “outrageous” translated into two Chinese words: 暴戾 (bàolì: ruthless and brutal) + 過分 (guòfèn: excessive and over the boundary), but the repetition of the word bàolì (ruthless and brutal) within the same clause complex is also highly charged with a negative evaluation of Madame Mao.

Summary

With more instances of the degrees of intensity and a higher percentage of total degree, the Chinese translation of Wild Swans displays greater intensity than the English source text. On one hand, the qualitative analysis in Section 4.4 has found that higher degrees of intensity are expressed in Chinese toward matters that concern the author herself, suggesting that the Chinese translation of this autobiography is a more personalised account and less interpretive of history. However, this higher intensity does not point to a particular ideological regularity. On the other hand, shifts in the translation of concordance lines that contain a degree of intensity show shifts in the evaluation of historical leaders, especially of the Maos: the Chinese translation reduces the criticism of Mao, but enhances that of Madame Mao. It may be unsurprising that the textual environment of the total degree of intensity has revealed such significant ideological shifts in translation, as total intensity expresses the highest level of interpersonal assessment. Lastly, some shifts and omissions have suggested a rectification in the Taiwanese translation of exaggeration and over-interpretation of Chinese politics and history in the English source text.

Conclusion

This study has elaborated the list of the English DEGREE OF INTENSITY based on Halliday and Mattiessen (2014) and proposed a list of Chinese DEGREE OF INTENSITY based on Lü (1982/2002). In addition, it has provided a case study to demonstrate how the proposed lists can be usefully applied to large corpora for the purpose of translation studies and contrastive linguistics using the concordance tool, SysConc. To identify and address typological differences, and ultimately to separate them from translators’ motivated selections, this study has not only compared the translation of the degree of intensity in Wild Swans with that in Mao’s Last Dancer but also with two reference corpora of the same era – FLOB and LCMC as well as their sub-corpora of a matching text type. Consistencies in results show typological preferences in Chinese for higher frequencies and higher degrees of intensity at least in the explicit/inscribed forms, especially with hěn (very) within high intensity. However, this does not mean that all shifts identified are attributed to such preferences. Rather, the increases in both the frequency and the degree of intensity in the translation of Wild Swans exceed typological expectations. In addition, the degree of intensity in the TT of Mao’s Last Dancer is considerably more faithful to the ST than shifts in Wild Swans, which is an indirect evidence that shifts of the degree of intensity in the translation of Wild Swans are, at least partially, the results of translators’ motivated selections in augmenting the interpersonal judgements to produce a more personal account in the translation with modified evaluation of historical leaders.

This study can be further expanded by taking into consideration of the more lexicalised and invoked types of intensity. The significance of the present study is four-fold. Firstly, it is a first attempt to propose two commensurable lists of the degree of intensity in English and in Chinese. Secondly, it highlights some possible semantic and ideological repercussions of a translator’s choice-making in handling the degree of intensity. Thirdly, it demonstrates a corpus-based approach to uncover latent grammatical patterns of degree of intensity in large corpora. Lastly, the feature lists built for this study are available upon request for those who are interested in contrastive studies of the degree of intensity in English (through FLOB) and in Chinese (through LCMC), and, potentially to other corpora of English and Chinese without major revision, as a tool for translation quality assessment and for investigating the intensity of interpersonal assessments.

Availability of data and materials

Access to SysConc can be requested by emailing the developer, Dr. Canzhong Wu, at Macquarie University in Sydney: Canzhong.Wu@mq.edu.au

All features built for this paper are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Notes

The classifier “Mandarin” is problematic in at least two senses. First, “Mandarin” does not specify a geopolitical entity as does “British”, hence obscuring the fact that its texts are extracted from publications in the Chinese mainland. Second, it makes the title sound as if LCMC is a spoken corpus when it is a written corpus, as Mandarin is generally considered as a spoken variant of the Chinese language(s); its distinctions from other dialects such as Cantonese are rarely marked explicitly in formal Chinese publications (i.e., colloquial Cantonese words are usually not used in formal publications), a main distinction of which is whether they are in simplified or traditional characters. Hence it may be more useful for the title to specify the type of charactery and geopolitical area.

Also, although LCMC is a collection of published works in Mainland China and Wild Swans was published in Taiwan, the main producers of the TT - the translator and the ST author – were both of Mainland Chinese background. Admittedly, the Taiwanese editors may have injected their stylistic preferences into the TT. This paper therefore took into considerations of a few degree of intensity that are commonly used in Taiwanese Mandarin, such as “蠻mán”, “超chāo” and “比較bǐjiào” (Fang 2014, 89–90); however, none of these were found in the TT of Wild Swans or Mao’s Last Dancer; a decision was then made to exclude these expressions.

A million words is the typical size of the first-generation corpus (Leech and Johansson 1978), and is not considered large in comparison to later corpora such as The citation “the British National Corpus (BNC) – 100 million word from 1980s and early 1990s (2007)” has been changed to “The British National Corpus, version 3 (BNC XML Edition) (2007)” to match the author name/date in the reference list. Please check if the change is fine in this occurrence and modify the subsequent occurrences, if necessary. The citation “The British National Corpus, version 3 (BNC XML Edition) (2007)” has been changed to “The British National Corpus, version 3 (BNC XML Edition) (2007)” to match the author name/date in the reference list. Please check if the change is fine in this occurrence and modify the subsequent occurrences, if necessary.The British National Corpus, version 3 (BNC XML Edition) (2007). Nevertheless, size is not all-important (Leech and Johansson 1978), and a balanced million-word corpus is by no means small: Matthiessen (2006) has recommended a limit of 15,000 words for a specialized English corpus, which echoes Sankoff’s view (1980) (in Milroy 1987, 21) that linguistic behaviour is more homogeneous.

Access to SysConc can be requested by emailing the developer, Dr. Canzhong Wu, at Macquarie University in Sydney, Australia: Canzhong.Wu@mq.edu.au

All features built for this paper are available upon request to the corresponding author.

In fact, there is no grammatical equivalence for the English verb “BE” and its cognates in Chinese: for instance, the word “是shì”, which is commonly considered as an equivalence of “BE”, has more restricted grammatical roles in construing relational processes.

Abbreviations

- FLOB:

-

Freiburg–LOB Corpus of British English

- LCMC:

-

The Lancaster Corpus of Mandarin Chinese

- SFL:

-

Systemic Functional Linguistics (SFL)

- ST:

-

Source text

- TT:

-

Target text

References

Biber, Douglas, Stig Johansson, Geoffrey Leech, Susan Conrad, and Edward Finegan. 1999. Longman grammar of spoken and written English. Harlow: Longman.

Butt, David. 1988. “Randomness, order and the latent patterning of text.” In Functions of Stye, by David Birch and Michael O'toole. London: Pinter.

Chang, Jung. 1991/2003. Wild swans - three daughters of China. New York: Touchstone.

Chang, Jung. 1992. Hong - Sandai Zhongguo Nuren de Gushi [orig. Wild swans – Three daughters of China]. Translated by Pu Zhang. Taipei: Heliopolis/Clio Culture.

Couthard, Malcome, and John Sinclair. 1975. Towards an analysis of discourse. London: Oxford University Press.

Fang, Qingming. 2014. Comparative analysis of the demonstrative markers in the Taiwanese variant and mainland variant of mandarin Chinese based on the spoken Chinese corpus. Shijie Huayu Jiaoxue 1: 88–99.

Halliday, Michael. 1991. Corpus studies and probabilistic grammar. In English corpus linguistics: Studies in honour of Jan Svartvik, ed. Aijmer Karin and Altenberg Bengt, 30–43. Essex: Longman.

Halliday, Michael, and Christian Mattiessen. 2014. Halliday's introduction to functional grammar. 4th ed. Oxon and New York: Routledge.

Halliday, Michael, and Edward McDonald. 2004. Mefatunctional profile of the grammar of Chinese. In Language typology: A functional perspective, ed. Alice Caffarel, James Martin, and Christian Matthiessen, 305–396. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Heine, Bernd, Ulrike Claudi, and Friederike Hunnemeyer. 1991. Grammaticalization: A conceptual framework. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hu, Yushu. 1962. Xiandai Hanyu. Shanghai: Shanghai Education Press.

Hundt, Marianne, Andrea Sand, and Rainer Siemund. 1999. Manual of Information to accompany The Freiburg – LOB Corpus of British English (‘FLOB’). Freiburg: Department of English. Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg.

Hunston, Susan. 2013. Systemic functional linguistics, corpus linguistics, and the ideology of science. Text & Talk 33 (4–5): 617–640.

Johansson, Stig, Geoffrey Leech, and Helen Goodluck. 1978. Manual of Information to Accompany the Lancaster-Oslo/Bergen Corpus of British English, for Use with Digital Computers. Oslo: Department of English, University of Oslo.

Lefevere, André. 1992. Translation, Rewriting and the Manipulation of Literary Fame. London and New York: Routledge.

Li, Cunxin. 2003/2009. Mao's last dancer. Melbourne: Penguin Group (Australia).

Li, Cunxin. 2009. In In Mao Zedong Shidai Zuihou de Wuzhe [orig. Mao’s last dancer] Translated by Xiaoyu Wang, ed. Hsin-Chin Lin. Taipei: China Times.

Li, Long. 2017. An examination of ideology in translation via modality: Wild swans and Mao’s last dancer. Journal of World Languages 4 (2): 118–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/21698252.2017.1417689.

Li, Long, Xi Li, and Jun Miao. 2019. A translated volume and its many covers – A multimodal analysis of the influence of ideology. Social Semiotics 29 (2): 261–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/10350330.2018.1464248.

Lu, Gusun. 2007. English-Chinese dictionary. 2nd ed. Shanghai: Shanghai translation publishing house. Accessed via Casio E-A200 electronic dictionary.

Lü, Shuxiang. 1982/2002. Lü Shuxiang Quanji. Shenyang: Liaoning Education Press.

Lyons, John. 1982. Deixis and subjectivity: Loquor, ergo sum? In Speech, place, and action: Studies in Deixis and related topics, ed. Robert Jarvella and Wolfgang Klein. Chichester and New York: Wiley.

Martin, James, and Peter White. 2005. Appraisal in English. London: Palgrave.

Matthiessen, Christian. 2006. Frequency profiles of some basic grammatical systems: An interim report. In System and corpus: Exploring connections, ed. Susan Hunston and Geoff Thompson, 103–142. London: Equinox.

McEnery, Tony, and Richard Xiao. 2004. The Lancaster corpus of mandarin Chinese (LCMC) (original version). Lancaster: Lancaster University.

Milroy, Lesley. 1987. Observing and Analysing natural language. Oxford: Blackwell.

Ouyang, Yu. 2013. Yi Xin Diao Chong: Yige Ao Hua Zuojia de Fanyi Biji. Taipei: Niang Publishing.

Penguin Australia. 2017. Mao’s last dancer Accessed 20 Oct, 2017. https://www.penguin.com.au/books/maos-last-dancer-9780143574323.

Sankoff, Gillian. 1980. The social life of language. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Shen, Jiaxuan. 2001. Two constructions with Hai in mandarin Chinese. Zhongguo Yuwen (6): 483–493.

The British National Corpus, version 3 (BNC XML Edition). 2007. Distributed by Oxford University computing services on behalf of the BNC consortium URL: http://www.natcorp.ox.ac.uk/.

The Freiburg-LOB Corpus (‘F-LOB’) (original version) compiled by Christian Mair, Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg.

Traugott, Elizabeth. 1999. The rhetoric of counter-expectation in semantic change: A study in Subjectification. In Historical semantics and cognition, ed. Andreas Black and Peter Koch. Berlin and New York: Nouton de Gruyter.

Wu, Canzhong. 2000. Modelling linguistic resources: A systemic functional approach. PhD Thesis. Sydney: Macquarie University.

Wu, Fuxiang. 2004. On the pragmatic function of the construction "X bu-bi Y. Z". Zhongguo Yuwen (3): 222–231.

Xiandai Hanyu Da Cidian. 2017. “十分”. Shanghai lexicographical publishing house Accessed via Casio E-A200 Electronic Dictionary.

Yuan, Yulin. 2008. Counter-expectation, additive relation and the types of pragmatic scale: The comparative analyses of the semantic function of Shenzhi and Faner. Dangdai Yuyanxue (2): 109–121.

Zhu, Dexi. 1982. Yufa Jiangyi. Beijing: Commercial Press.

Acknowledgements

Long received his doctoral scholarship from the Australian Government (APA: S2-14).

About the authors

Dr. Long Li is a recent graduate from the Department of Linguistics at Macquarie University in Sydney, Australia. His work examines the influence of political ideology in the Chinese translations of politically volatile English works written by Chinese migrant writers. He also works as an interpreter, translator, and teacher. His interests include systemic functional linguistics (SFL), translation studies, and ideology.

Dr. Canzhong Wu is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Linguistics, Macquarie University. He specializes in SFL, the development of computational tools for multilingual grammatical reference resources, and translation studies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LL initiated the study, collected and analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript. CW provided technical support and guidance for reference corpora and methodology. Both critically revised the draft. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, L., Wu, C. DEGREE OF INTENSITY in English-Chinese translation: a corpus-based approach. Functional Linguist. 6, 3 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40554-019-0068-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40554-019-0068-1