Abstract

Optical and FTIR spectroscopy was employed to study the properties of 80GeS2-20Ga2S3-CsCl chalcohalide glasses with CsCl additives in a temperature range of 77–293 K. It is shown that CsCl content results in the shift of fundamental absorption edge in the visible region. Vibrational bands in FTIR spectra of (80GeS2-20Ga2S3)100 − х (СsCl) x (x = 5, 10, and 15) are identified near 2500 cm−1, 3700 cm−1,, around 1580 cm−1, and a feature at 1100 cm−1. Low energy shifts of vibrational frequencies in glasses with a higher amount of CsCl can be caused by possible thermal expansion of the lattice and nanovoid agglomeration formed by CsCl additives in the inner structure of the Ge-Ga-S glass.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Modern IR photonics emphasizes a significant importance of glassy functional materials with improved exploitation characteristics [1–3]. Among the promising media for applications of photonics are specific glasses, such as non-oxide glassy-like materials with a high content of chalcogens (S, Se, Te), which are also widely known as the chalcogenide glasses (ChGs) [4, 5]. Main developments concerning the preparation of such materials include different methods of their technological and post-technological structural modification using external influences, such as thermal annealing, high-energy irradiation, and laser beam treatment [5–8]. Technical possibilities of these modification methods, however, are, to a large extent, restricted by peculiarities of a vitreous state with characteristic effects of natural physical aging, functional non-reproducibility, and thermodynamic instability in view of high affinity to chemical reactivity.

That is why the commonly used optimization of ChG is connected with traditional chemical compositional modification based on doping possibilities with additional components introduced into the glass matrix to attain new, sometimes unusual, properties. The principal functionality of ChG is determined by their excellent IR transparency. A wide range including both commercially important atmospheric telecommunication windows at 3–5 and 8–12 μm up to a space telecommunication domain at 20–25 μm can be effectively combined with the transparency of halide compounds in a visible range by developing mixed chalcogenide-halogenide glasses such as Ge-Ga-S-CsCl systems [9, 10]. The mix of unique optical properties with high flexibility in composition and fabrication methodology makes these ChG systems compelling for IR photonics [11]. The exceptional IR transparency associated with suitable viscosity/temperature dependence creates a good opportunity for developing ChG-based molded optics for IR devices.

In [12, 13], we studied the influence of CsCl amount on an atomic-deficit sub-system (void- or pore-type structure formed due to the lack of atoms at some of glassy network sites) in Ge-Ga-S-CsCl chalcohalide composition. In this work, we analyze the CsCl effect on the optical and vibrational properties of (80GeS2-20Ga2S3)100 − x (CsCl) x glasses with x = 5, 10, and 15.

Methods

GeS2-Ga2S3-CsCl chalcogenide glasses were sintered from Ge, Ga, S, and CsCl compounds (99.999 % purity), as described in details elsewhere [14–16]. Raw materials were melted at 850 °C in a silica tube for several hours. The (80GeS2-20Ga2S3)100 − х (СsCl) x (x = 5, 10, and 15) glasses were annealed at 15 °C below a glass transition temperature (T g) for each of the glasses [16] to minimize inner strains. Such amount of CsCl additives is optimal in order to modify Ge-Ga-S glasses before future doping of these materials by rare-earth ions. For the purpose of convenience, the obtained glasses of (80GeS2-20Ga2S3)100(СsCl)0, (80GeS2-20Ga2S3)95(СsCl)5, (80GeS2-20Ga2S3)90(СsCl)10, and (80GeS2-20Ga2S3)85(СsCl)15 hereafter are referred to as (CsCl)0, (CsCl)5, (CsCl)10, and (CsCl)15, respectively.

Optical spectra were measured using a Cary5 (Varian) short-wavelength spectrophotometer. A Bruker Vector 22 instrument was exploited to record the spectra in the mid and far-infrared regions [16]. IR spectroscopy at different temperatures was carried out at the infrared beamline SINBAD of the Daphne Light synchrotron IR facility [17–21]. The infrared transmission spectra were collected using a Vertex 70V FTIR spectrometer equipped with a Janis ST-100-FTIR (Janis Research Company, LLC, Woburn, MA) continuous flow cryostat and a room temperature DTGS detector. The outer cryostat windows were made of CaF2. The temperature points (293, 220, 150, and 77 K) were set with a LakeShore 331 temperature controller and kept constant, controlling the flux of liquid nitrogen and heating power during the necessary measurement procedure. The heating/cooling rate in experiments was set to 10 K min−1. The transmission spectra were acquired in the vacuum between 4500 and 900 cm−1 with a spectral resolution of 4 cm−1, performing 128 scans.

Results and Discussion

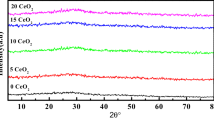

The transmission in the visible and infrared region of spectra for ChG under study measured at 293 K is shown in Fig. 1. Samples with x = 0 and x = 5 are essentially transparent down to 500 nm. A further increase of the CsCl content in the base GeS2-Ga2S3 glassy matrix results in a shift of the absorption edge towards shorter wavelengths which is in line with the earlier reports [14, 16]. The transmission increases with a CsCl concentration from 60 % in CsCl0 to 80 % in CsCl15. As was shown in [16], by adding up to 15 mol% of the alkali halide in the glassy matrix, the bandgap energy evolves from 2.64 to 2.91 eV. From a structural point of view, the addition of less than 15 % of CsCl in GeS2-Ga2S3 glasses is characterized by the formation of GaS4 − x Cl x tetrahedra that are dispersed in the glass network. Hence, the average number of Ga–S bonds decreases in favor of the average number of Ga–Cl bonds. One of the observed features for (80GeS2-20Ga2S3)100 − х (СsCl) x (x = 0, 5, 10, and 15) glasses in the vis-IR transmission is the sharp peak at 4 μm (for base glass, black line) that is attributed to S–H stretching and is considerably damped for samples with CsCl. There are also features at 6300 nm corresponding to H2O, in which 6700 and 2900 nm are related to O–H stretching vibrations. The intensity of absorption bands associated with water increase with the CsCl amount, confirming the hygroscopicity of CsCl [16].

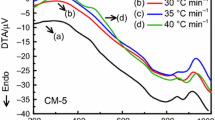

The results of FTIR measurements at different temperatures are shown in Figs. 2 and 3. First, the absorbance for GeS2-Ga2S3 as a function of CsCl content was analyzed at 77, 150, 220, and 293 K and is presented in Fig. 2. Three main vibrational bands are identified for (80GeS2-20Ga2S3)100 − х (СsCl) x (x = 5, 10, and 15) glasses. The fundamental S–H absorption band is observed at 2500 cm−1 [22]. The maxima at ~3700 cm−1 are very likely an O–H-related absorption, common for many chalcogenide glasses [22]. The band at around 1580 cm−1 corresponds to H2O impurity that resides in structural voids [23]. The feature at ~1100 cm−1 could be due to inorganic sulfate ion absorption [24]. For each temperature, the intensities of the identified bands are increased with the CsCl amount in the 80GeS2-20Ga2S3 ChG. The S–H and O–H absorption bands are very weak for (80GeS2-20Ga2S3)95(СsCl)5 glasses. There is a minor band near 1580 cm−1 that corresponds to H2O. Obviously, the structures of Ge-Ga-S glasses containing a smaller amount of CsCl are more stable against the adsorption of water due to a small amount of free-volume voids [12, 25]. Increasing of CsCl content in (80GeS2-20Ga2S3)100 − х (СsCl) x glasses to x = 10 and x = 15 results in higher intensities of the bands corresponding to 1580 and ~3700 cm−1 at all measured temperatures (Fig. 2). These transformations are connected with changes in the inner structure of ChG with CsCl that facilitate a more intensive H2O adsorption. Most probably, (CsCl)15 glasses could be enriched by the water molecules, having an effect on its structure. As it follows from the measurement results, main vibration bands are somewhat shifted to lower energies at 77 and 150 K, but as the temperature rises up to 220 and 293 K, these changes become more obvious. Such temperature shifts of vibrational frequencies can be caused by possible thermal expansion of the lattice [26] and nanovoid agglomeration. The fact of the nanovoid formation induced by CsCl additives in Ge-Ga-S has been definitely confirmed by positron annihilation lifetime spectroscopy [12, 15, 25, 27–29].

The vibrational spectra of (80GeS2-20Ga2S3)100 − х (СsCl) x (x = 5, 10, and 15) glasses collected at different temperatures for each composition are shown in Fig. 3. It can be observed that the bands located near 1580 cm−1 appear for all glasses and show no shifts. In the (CsCl)5 and (CsCl)10 ChG samples, there is a very slight shift of the S–H absorption band located near 2500 cm−1 at elevating temperatures. However, the temperature shift of vibrational frequencies towards lower energies for (CsCl)15 glasses is detected for the S–H vibrational band and O–H-related peaks also shift with the increase of temperature from 77 to 293 K. We tend to think that this effect may be due to the differences in water absorption in the structure at higher temperatures. All transformations of vibrational modes of (80GeS2-20Ga2S3)85(СsCl)15 glasses are related to the excessive amount of CsCl additive, resulting in the damage to the inner structure of the host material.

Conclusions

The CsCl addition effects on the optical and vibrational spectra for GeS2-Ga2S3-CsCl glasses are investigated. It is demonstrated that the transmission in the visible region increases with a CsCl concentration from 60 % in (CsCl)0 to 80 % in (CsCl)10 and (CsCl)15. A sharp peak at 4000 nm for a base (CsCl)0 glass is attributed to S–H stretching and is considerably damped for samples with CsCl in the mid-IR spectra. There are also features at 6300 nm corresponding to H2O, in which 6700 and 2900 nm are related to O–H stretching vibrations. The intensity of absorption bands associated with water increased with the CsCl amount, confirming the hygroscopicity of CsCl. It is established that for each measured temperature (77, 150, 220, and 293 K), the intensities of the observed vibrational bands increase with the CsCl amount in the 80GeS2-20Ga2S3 ChG. The principal vibrational bands centered near 1100, 1580, 2500, and 3700 cm−1 in (CsCl)15 glasses are slightly shifted to lower energies between 77 and 150 K. The shift is more pronounced between 220 and 293 K. Such temperature shifts of vibrational frequencies can be caused by possible thermal expansion of the lattice and agglomeration of nanovoids formed by CsCl additives. Temperature dependences of FTIR spectra also indicate the lower-energy shift of vibrational frequency of the S–H-related band for (CsCl)15 glasses and the shift of O–H-related peaks at elevating temperatures.

References

Eggleton BJ (2010) Chalcogenide photonics: fabrication, devices and applications. Introduction. Opt Express 18(25):26632–26634

Ródenas A, Martin G, Arezki B, Psaila N, Jose G, Jha A, Thomson R (2012) Three-dimensional mid-infrared photonic circuits in chalcogenide glass. Opt Lett 37(3):392–394

Cherif R, Salem AB, Zghal M, Besnard P, Chartier T, Brilland L, Troles J (2010) Highly nonlinear As2Se3-based chalcogenide photonic crystal fiber for midinfrared supercontinuum generation. Opt Eng 49(9):095002

Zakery A, Elliott SR (2003) Optical properties and applications of chalcogenide glasses: a review. J Non-Cryst Solids 330(1):1–12

Lezal D, Pedlikova J, Zavadil J (2004) Chalcogenide glasses for optical and photonics applications. J Optoelectron Adv Mater 6(1):133–137

Fairman R, Ushkov B (2004) Semiconducting Chalcogenide Glass I: Glass Formation, Structure, and Simulated Transformations in Chalcogenide Glasses. Elsevier Academic Press, Amsterdam – Boston – London – New York – Oxford – Paris – San Diego – San Francisco – Singapore – Sydney – Tokyo, 78. p 306. ISSN:0-12-752187-9. ISSN:0080-8784 (series).

Efimov OM, Glebov LB, Richardson KA, Van Stryland E, Cardinal T, Park SH, Bruneel JL (2001) Waveguide writing in chalcogenide glasses by a train of femtosecond laser pulses. Opt Mater 17(3):379–386

Zhang XH, Guimond Y, Bellec Y (2003) Production of complex chalcogenide glass optics by molding for thermal imaging. J Non-Cryst Solids 326:519–523

Chung WJ, Heo J (2003) Spectroscopic properties and local structure of Eu3+ in Ge–Ga–S–CsBr (or CsCl) glasses. J Am Ceram Soc 86(2):286–290

Ledemi Y, Bureau B, Calvez L, Floch ML, Rozé M, Lin C, Messaddeq Y (2009) Structural investigations of glass ceramics in the Ga2S3-GeS2-CsCl system. J Phys Chem B 113(44):14574–14580

Eggleton BJ, Luther-Davies B, Richardson K (2011) Chalcogenide photonics. Nat Photonics 5(3):141–148

Klym H, Ingram A, Shpotyuk O (2016) Free-volume nanostructural transformation in crystallized GeS2–Ga2S3–CsCl glasses. Mater Werkst. doi:10.1002/mawe.201600476

Klym H, Ingram A, Shpotyuk O, Szatanik R (2015) Free-volume study in GeS2-Ga2S3-CsCl chalcohalide glasses using positron annihilation technique. Phys Procedia 76:145–148

Calvez L, Lin C, Rozé M, Ledemi Y, Guillevic E, Bureau B, Allix M, Zhang X. Similar behaviors of sulfide and selenide-based chalcogenide glasses to form glass-ceramics. Proc SPIE 2010:759802-1-16.

Shpotyuk O, Calvez L, Petracovschi E, Klym H, Ingram A, Demchenko P (2014) Thermally-induced crystallization behaviour of 80GeSe2–20Ga2Se3 glass as probed by combined X-ray diffraction and PAL spectroscopy. J Alloys Compounds 582:323–327

Masselin P, Le Coq D, Calvez L, Petracovschi E, Lepine E, Bychkov E, Zhang X (2012) CsCl effect on the optical properties of the 80GeS2–20Ga2S3 base glass. Appl Phys A 106:697–702

Bolesta I, Velgosh S, Datsiuk Y, Karbovnyk I, Lesivtsiv V, Kulay T, Piccinini M (2007) Optical, infrared and electron-microscopy studies of (Cdi)n metallic clusters in layered CdI2 crystals. Radiat Meas 42(4):851–854

Karbovnyk I, Piskunov S, Bolesta I, Bellucci S, Cestelli Guidi M, Piccinini M, Spohr E, Popov AI (2009) Far IR spectra of Ag2CdI4 at temperature range 10–420 K: complementary experimental and first-principle theoretical study. Eur Physical J B 70(4):443–447

Polovynko I, Rykhlyuk S, Karbovnyk I, Koman V, Piccinini M, Cestelli Guidi M (2009) A new method of growing K2CoxNi1-x(SO4)2*6H2O (x = 0; 0.4; 0.8; 1) mixed crystals and their spectral investigation. J Cryst Growth 311(23):4704–4707

Bellucci S, Popov AI, Balasubramanian C, Cinque G, Marcelli A, Karbovnyk I, Savchyn V, Krutyak N (2007) Luminescence, vibrational and XANES studies of AlN nanomaterials. Radiat Meas 42(4):708–711

Balasubramanian C, Bellucci S, Cinque G, Marcelli A, Cestelli Guidi M, Piccinini M, Popov A, Soldatov A, Onorato P (2006) Characterization of aluminium nitride nanostructures by XANES and FTIR spectroscopies with synchrotron radiation. J Phys Condens Matter 18(33):S2095

Huang CC, Hewak D, Badding J (2004) Deposition and characterization of germanium sulphide glass planar waveguides. Opt Express 12(11):2501–2506

Hewak DW, Brady D, Curry RJ. Chalcogenide glasses for photonics device applications. Research Signpost, Kerala, India, Chap, 2; 2010.

Colthup N, Daly L, Wiberley S: Introduction to infrared and Raman spectroscopy: Academic Press Inc., 1975, 356 p.ISBN 0-12-182552-3.

Klym H, Ingram A, Shpotyuk O, Hotra O, Popov AI (2016) Positron trapping defects in free-volume investigation of Ge-Ga-S-CsCl glasses. Radiat Meas. doi:10.1016/j.radmeas.2016.01.023

Savchyn P, Karbovnyk I, Vistovskyy V, Voloshinovskii A, Pankratov V, Cestelli Guidi M, Mirri C, Myahkota O, Riabtseva A, Mitina N, Zaichenko A, Popov AI (2012) Vibrational properties of LaPO4 nanoparticles in mid- and far-infrared domain. J Appl Phys 112(12):124309

Klym H, Ingram A, Shpotyuk O, Calvez L, Petracovschi E, Kulyk B, Serkiz R, Szatanik R (2015) “Cold” crystallization in nanostructurized 80GeSe2-20Ga2Se3 glass. Nanoscale Res Lett 10:49

Ingram A, Klym HI, Shpotyuk OI. Ge-Ga-S/Se glasses studied with PALS technique in application to chalcogenide photonics. Proceeding of the International Conference on Advanced Optoelectronic and Laser CAOL, 2013:386-387.

Shpotyuk O, Filipecki J, Ingram A, Golovchak R, Vakiv M, Klym H, Balitska V, Shpotyuk M, Kozdras A (2015) Positronics of subnanometer atomistic imperfections in solids as a high-informative structure characterization tool. Nanoscale Res Lett 10(1):1–5

Acknowledgements

The FTIR experiments at INFN-LNF were supported by the European Community in the frame of CALIPSO program under FP7 – Transnational Access to Research Infrastructures (TARI), Contract No. 312284. H. Klym thank the Lviv Polytechnic University under Doctoral Program and support via the Project DB/KIBER (No. 0115U000446), A.I. Popov thanks the VBBKC L-KC-11-0005 project Nr. KC/2.1.2.1.1/10/01/006, 5.4 for the funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ Contributions

HK performed the experiments to study the optical properties of Ge-Ga-S-CsCl glasses in a visible range and prepared the draft of the article. MCG, HK, and IK performed the measurements of FTIR spectra and processed the obtained results. AIP supervised the work. MCG and AIP interpreted the FTIR results. OH contributed to the identification and analysis of the infrared bands. IK finalized the text and graphical material. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Klym, H., Karbovnyk, I., Guidi, M.C. et al. Optical and Vibrational Spectra of CsCl-Enriched GeS2-Ga2S3 Glasses. Nanoscale Res Lett 11, 132 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s11671-016-1350-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s11671-016-1350-8