Abstract

COVID-19 pandemic required compulsory social isolation; thus, people have been forced to stay at home for months in the most part of world. The curfew has been specially imposed to people aged 65 and above, who are supposedly most affected by devastating effects of COVID-19 disease in Turkey. However, the curfew could cause negative mental difficulties like depression tendency. We aimed to determine the depression tendency by using depression indicators such as insomnia, poor appetite, despair, weariness, anxiety/fear, dereliction, lack of concentration, anger and trashiness on curfew-imposed older people aged 65 and above during outbreak. The participants (n = 119) were the students of Tazelenme University, the university of third age (U3A), of Antalya Campus. The inter-cluster linkage method and the squared Euclidean distance measurement level were used to construct clusters. Frequency, percentage, t-test, Pearson correlation tests were used for further analysis of the clusters. Two clusters were recovered. Statistically significant differences were found between the two clusters by mean comparison values in relation to age, years of education and household factors. Participants of Cluster 2 (average age 64.40) appeared to be more affected and more tend to be depressive than participants of Cluster 1 (average age 68.61). The results indicated a relationship between curfew and depression tendency.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

The social distancing and isolation measures taken during COVID-19 pandemic may have impacts on mental health [1]. Curfews has been introduced as mandatory social isolation during outbreak in many countries. The links between social isolation/deprivation and depression have been frequently noted [2, 3]. Social deprivation is the lack of routine social relationships and the lack of attention of people to social relationships [4] and it can be a serious stress factor. The legal and social pressures driven by the mandatory curfew are therefore quite likely to put stress on older people.

Epidemiological studies conducted in various countries have shown that approximately 17% of the population experience depression at some point of their lives. The prevalence among those over age 60 is around 15%. This rate becomes doubled for the people who live in nursing homes or need to stay in hospital for long times. Many older people are ashamed of their depressive symptoms and tend to dissimulation [5]. Depression is linked to feelings of emotional loneliness, isolation, and exclusion [6]. However, there is some evidence that younger people are more likely to experience anxiety [7], depression, and stress [8] under curfew conditions during the outbreak. On the other hand, the social isolation particularly was prominent among older people during outbreak and they have been recognised as vulnerable groups in terms of depression or suicide [9, 10].

Although, the depression tendency was conventionally estimated by a series of items in questionnaires or standardized interviews, some recent studies predict it by analysis of image, text and behaviour of people, even communicated in social media [11–13]. Therefore, the depression tendency may be characterized as expression or reflection of some of the items included in the depression symptoms inventory [14, 15].

Older people live not only with family members but also establish social relationships with friends and neighbours in clubs, sports groups, or congregations [16]. Santini and colleagues [17], recently demonstrated that, social disconnectedness predicts higher level of perceived isolation, and thus, increase in symptoms of depression and anxiety. Conversely, depression and anxiety symptoms predicted higher amounts of perceived isolation, and related social disconnectedness.

The older people in compulsory isolation process in Turkey, has become dependent on others (for shopping, healthcare service access, social interaction, etc.). It seems that “dependent people need others more; therefore, it is understandable that reduced social contact causes them to feel lonelier” [16]. So far, no empirical information is available on the possible consequences of forced isolation on people aged 65 and above in Turkey.

During the COVID-19 pandemic (outbreak), social distance practices and isolation have become essential precautions to provide the protection and safety of older people. However, this has caused anxiety and some mental challenges for older people [18]. Turkish government has imposed curfew for the people aged 65 and over, the most vulnerable group to COVID-19 outbreak. The curfew restrictions lasted approximately two months. Considering that joy of life usually results from living with others [19], “the impact of curfew may reduce joy of life and increase related depressive tendency” seems to be a reasonable assumption. Older people who do not have close family or friends and depended on the support of voluntary services or social care, could be faced with additional stress factors [20]. Here, we aimed to explore the impact of compulsory curfew on depression tendency in older people.

EXPERIMENTAL

The total number of participants was 119 including 57 male and 62 female who are students of 60+ Tazelenme University of Antalya Campus. It is a 3rd age university, has been set up as a social responsibility project that provides free 4-year education since 2016 with the principle of 60+ years of lifelong learning [21].

According to the International Classification of Diseases 10th, depression syndromes were divided into main syndromes and other common syndromes. Main syndromes were depressed mood, loss of interest, and reduced impulse. The other common syndromes were lack of concentration, decreased self-esteem, feelings of guilt, feelings of worthlessness, pessimistic expectations for the future, suicidal thoughts, sleep disorders, decreased appetite, fatigue, weakness, lack of energy, lack of interest, exaggerated worries and fears, negative thoughts, cognitive deficits, and exaggerated sense of pain [5]. Since we aimed to find out likely depression tendency but not a formal diagnosis of mental illness, a simple mobile phone questionnaire was conducted. In addition, the application of formal depression test tools was almost impossible due to practical difficulties and for the sake of rapid data collection, only some depression indicators were considered. The following depression indicators were included: insomnia, poor appetite, despair, weariness, anxiety/fear, dereliction, lack of concentration, anger, trashiness [5]. The questions were structured in following way to avoid possible ambiguities: “In general, how did you suffer from insomnia after the curfew when you compare with the period before the curfew?” (Answer: often, rare, no). For the validation of questionnaire, we examined the Cronbach’s alpha value [22], the estimate of internal consistency of the items. The overall instrument had high reliability (alpha = 0.90). The mean inter-item correlation were ranged from 0.25 to 0.50, confirming internal consistency. Finally, for the bottom-up procedure [23], variances of items (0.52–0.75) and corrected item-total correlation (0.50–0.87) calculated and reported with acceptable ranges.

The level of significance was chosen as “alpha = 0.05.” The communication with participants was established through WhatsApp software during data collection. The questions were sent to the participants in written and the participants conveyed their answers in the same way.

The statistical hypothesis (null hypothesis) of this study is that “the curfew-imposed older people has not experienced depression tendencies or risks due to curfew.” To test this hypothesis, two age groups, the 60–64 age group and the 65 and above age group were compared, and cluster analysis was used to test the research hypothesis. This method classifies objects or cases into relative groups [24]. The cluster analysis constructs groups (or clusters) based on observations as similar as possible within a group, while observations as different as possible in a different group.

IBM SPSS Statistics 23.0 software were used for data analysis. The inter-cluster linkage method and the squared Euclidean distance measurement level were preferred to construct clusters [25, 26]. Frequency and percentage tests were utilised to demonstrate demographics (gender, marital status, education) of participants and distribution of answers given to questions. Pearson correlation test was used for comparison of depression tendency indicators to the main age values calculated for clusters. t-Test was conducted to compare the mean values of depression indicators between clusters as well as the mean values of depression indicators of gender and the mean age, education level and household numbers in relation to clusters [27].

Marginal Normalization

In this study, an ordinal-scale questionnaire was utilised to find out depression tendency. Due to uncertain distance between answers, ordinal-scale data is not suitable for clustering method. Ordinal-scaled data were adapted to the standard normal distribution by using marginal normalization method of Fechner (1860) given by [23]. Since “1 = often,” “2 = rare” and “3 = no” for the answers given by ordinal scale, negative values in the normal distribution are closer to “often”; positive values are closer to be “rare” or “no.”

Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval was taken from the Ethical Board of National Society of Social and Applied Gerontology, Antalya, Turkey (Approval issue no: 2016.204.14.04.20 etk:-17). Before initiating the survey, brief information was provided to participants in detail by telephone regarding the purpose and objectives of the study. Verbal informed consent of participation was obtained before implementation of questionnaire. Participants were also informed that they have a right to withdraw their participation at any time during the study.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

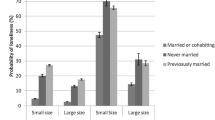

Demographical information of participants was presented in Fig. 1. Forty-nine of the participants (41.2%) were between the ages of 60–64 (group 1: exempted from curfew) and 70 (58.8%) were 65 and over (group 2: imposed to curfew). Most of them were married in both groups (Group 1: 95.9%; Group 2: 81.5%). The twenty-nine of participants (57.1%) in Group 1 and 34 of them (48.6%) in Group 2 were female.

The cluster analysis recovered two clusters based on the similarity of answers given to research questions and properties of clusters were examined to assess depressive effect of the curfew on older people. Cluster 1 included 78 participants (65.5%) while Cluster 2 recovered 41 participants (34.5%). The average age was 64.40 (SD: 3.54) years and in Cluster 1, 68.61 (SD: 3.36) years in Cluster 2 (Table 1). Total years of education is 12.32 in Cluster 1 and 9.83 in Cluster 2 (see Table 1). The curfew-imposed participants were mostly included in Cluster 2 while, Cluster 1 consisted mostly of curfew-exempted participants. But there were also some curfew-imposed participants in Cluster 1. Within the clusters average ages compared by t‑test and statistically significant difference (t-test: ‒6.276, p < 0.001) was found (see Table 1).

Among participants who stated that they “never” (said no) experienced the problems were approximately between 30–60%, whereas the percentage of those experienced problems “often” varies between 15–35%. The gender was not statistically significant in general but showed statistically significant difference (Table 2) in relation to one of the nine indicators (The question of “Trashiness” χ2 = 12.015; df = 2; p = 0.002).

No statistically significant difference was found in terms of gender distribution between two clusters (linkage between clusters). There were 42.3% male and 57.7% female participants in Cluster 1 while 58.5% male and 41.5% female participants in Cluster 2. On the other hand, statistically significant difference was found between the clusters by mean comparison values of t-test, in relation to age, years of education and household factors (see Table 1). Cluster 1 consists of younger and more educated participants with more crowded households. As presented in Table 3, average values of Cluster 1 were positive, and the average values of Cluster 2 were mostly negative. Correlation coefficients of age of clusters according to depression indicators were presented in Table 4.

The COVID-19 outbreak arouses considerable worry, concern, fear, stress, and anxiety in large populations including older adults in the world. The various changes on daily activities, routines and livelihoods of ordinary people have caused various emotional effects like loneliness feeling, depression and so on [28, 29]. The restrictions imposed to people 65 aged and over, started on March 22, 2020, with Circular no. 5762 issued by Ministry of Interior, Republic of Turkey [30] and lasted on June 9, 2020.

The results revealed that curfew imposed older people has tendency to depression. A significant statistical difference was found between two cluster in most depressive indicators.

However, no difference was found between clusters only for one indicator (“insomnia”) (see Table 3). Sleep disorders/disturbance has been linked to perceived social isolation [2] and/or effected by social isolation [3]. However, the mentioned studies did not conduct during compulsory curfews of outbreak. Although no statistically significant differences were found between genders, females perceived higher psychological impact of outbreak in a study conducted in India [31]. We assume that sleep disorders are linked to depression when it is experienced for the first time. Additionally, individuals in Cluster 1 (which relatively constitutes younger aged) got more positive scores but more tendency to experience insomnia symptoms. However, participants of Cluster 2 got more negative scores and more tend to depression (see Table 3).

Since there were older individuals in Cluster 2, it may be assumed that the depression tendency in this cluster is related to age. As gerontologists often point out the age is not a strong factor on depression [32]. Rather different dimensions of social exclusion have certain effects on depression [33]. The present study reveals that age is not an important factor in depression tendency. Correlation coefficients of age of clusters, was calculated according to depression indicators (see Table 4). In Cluster 1, a statistically significant correlation was found for 6 out of 9 questions in terms of age. On the other hand, in Cluster 2, statistically significant correlation was found only for one question. This clearly indicate that the curfew has significant impact on older people in terms of depression tendency. Yet, the age factor seems to play a role in Cluster 1 which was not affected by the curfew. It was also found that five of the answers with a significant negative correlation, (increased reply of “often” with increasing age). However, considering that participants of this cluster were not affected by the curfew, factors other than age must have played a role. We assume one of the main affects may be keeping away older people from their social roles, i.e., daily out-of-home routines.

CONCLUSIONS

The older people who were suddenly cut off from ordinary social relations, has experienced the curfew as a process of pressure as well as exclusion from and accusing of social environment. The older individuals have also become more dependent to others during the curfew. But this type of “curfews” seems to be meaningless. The older people who stayed at home did not believe that curfews could stop the outbreaks [34]. According to statistics of Turkish Ministry of Health [35], no significant decline was observed in the number of cases between curfew and free periods. It is also unclear whether the curfew really protects the older people from COVID-19. Five of Tazelenme University students who were imposed to a curfew, died during the outbreak. Although this research depicts that there is an association between depression and the curfew, the results must be judged with caution since it is a limited study representing only student population of Tazelenme University of Antalya Campus.

REFERENCES

Vahia, I.V., Blazer, D.G., Smith, G.S., et al., COVID-19, mental health and aging: a need for new knowledge to bridge science and service, Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry, 2020, vol. 28, no. 7, pp. 695–697. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2020.03.007

Bhatti, A.B. and Haq, A.U., The pathophysiology of perceived social isolation: effects on health and mortality, Cureus, 2017, vol. 9, no. 1, p. e994. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.994

Choi, H., Irwin, M.R., and Cho, H.J., Impact of social isolation on behavioral health in elderly: systematic review, World J. Psychiatry, 2015, vol. 5, no. 4, pp. 432–438. https://doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v5.i4.432

Tewes, U. and Wildgrube, K., Psychologie-Lexikon, Munich: Oldenbourg Verlag, 1999.

Kasper, S., Depression, angst und gedächtnisstörungen, in Hoffnung Alter: Forschung, Theorie, Praxis, Rosenmayr, L. and Böhmer, F., Eds., Vienna: WUV Universitätsverlag, 2003, pp. 45–49.

Smith, J. and Baltes, P., Altern aus psychologischer perspektive: trends und profile im hohen alter, in Die Berliner Altersstudie, Mayer, K.K. and Baltes, P., Eds., Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 1996, p. 238.

Alyami, H.S., Naser, A.Y., Dahmash, E.Z., et al., Depression and anxiety during 2019 coronavirus disease pandemic in Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional study, Int. J. Clin. Pract., 2020 (in press). https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.09.20096677

Alghamdi, B.S., AlAtawi, Y., AlShehri, F.S., et al., Psychological distress during covid-19 curfews and social distancing in Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional study, 2020 (in press). https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-40296/v1

Panchal, N., Kamal, R., Orgera, K., et al., The implications of COVID-19 for mental health and substance use. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/the-implications-of-covid-19-for-mental-health-and-substance-use/. Accessed June 24, 2020.

Wand, A.P.F., Zhong, B.L., Chiu, H.F.K., et al., Covid-19: the implications for suicide in older adults, Int. Psychogeriatr., 2020, vol. 32, no. 10, pp. 1225–1230.

Huang, Y., Chiang, C., and Chen, A., Predicting depression tendency based on image, text and behavior data from Instagram, Proc. 8th Int. Conf. on Data Science, Technology and Applications, Prague, Setubal: SciTePress, 2019, vol. 1, pp. 32–40. https://doi.org/10.5220/0007833600320040

Yang, C., Lai, X., Hu, Z., et al., Depression tendency screening use text based emotional analysis technique, J. Phys.: Conf. Ser., 2019, vol. 1237, no. 3. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1237/3/032035

Xie, H., Jiang, D., and Zhang, D., Individuals with depressive tendencies experience difficulty in forgetting negative material: two mechanisms revealed by ERP data in the directed forgetting paradigm, Sci. Rep., 2018, vol. 8, p. 1113. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-19570-0

Aarø, L.E., Herbeć, A., Bjørngaard, J.H., et al., Depressive episodes and depressive tendencies among a sample of adults in Kielce, south-eastern Poland, Ann. Agric. Environ. Med., 2011, vol. 18, no. 2, pp. 273–278.

Kuroda, Y., Iwasa, H., Goto, A., et al., Occurrence of depressive tendency and associated social factors among elderly persons forced by the Great East Japan Earthquake and nuclear disaster to live as long-term evacuees: a prospective cohort study, BMJ Open, 2017, vol. 7, no. 9, p. e014339. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014339

Lehr, U., Psychologie des Alterns, Wiebelsheim: Quelle & Meyer, 2003, pp. 287–293.

Santini, Z.I., Jose, P.E., Cornwell, E.Y., et al., Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and symptoms of depression and anxiety among older Americans (NSHAP): a longitudinal mediation analysis, Lancet: Publ. Health, 2020, vol. 5, no. 1, p. e62-e70.

Girdhar, R., Srivastava, V., and Sethi, S., Managing mental health issues among elderly during COVID-19 pandemic, J. Geriatr. Care Res., 2020, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 29–32.

Gillet, R., Depressionen: Ein Ratgeber aus Ganzheitlicher Sicht, Ravensburg: Otto and Maier, 1988.

Armitage, R. and Nellums, L.B., COVID-19 and the consequences of isolating the elderly, Lancet: Publ. Health, 2020, vol. 5, no. 5, p. e256. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30061-X

Tufan, İ., 60+ Tazelenme University: Education of older adults in Turkey: comments and recommendations, 2021 (in press).

Taber, K.S., The use of Cronbach’s alpha when developing and reporting research instruments in science education, Res. Sci. Educ., 2018, vol. 48, pp. 1273–1296. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-016-9602-2

Zijlmans, E.A.O., Tijmstra, J., van der Ark, L.A., and Sijtsma, K., Item-score reliability as a selection tool in test construction, Front. Psychol., 2019, vol. 9, p. 2298. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02298

Hartung, J. and Elpelt, B., Multivariate Statistik, Munich: Oldenbourg, 1992.

Bühl, A., SPSS 18 (Ehemals PASW): Einführung in die Moderne Datenanalyse, Munich: Pearson Studium, 2010.

Backhaus, K., Erichson, B., Plinke, W., and Weiber, R., Multivariate Analysemethoden: Eine Anwendungsorientierte Einführung, Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag, 2011.

Kremelberg, D., Pearson’s r, chi-square, T-test, and ANOVA, in Practical Statistics: A Quick and Easy Guide to IBM

SPSS

SPSS

Statistics, STATA, and Other Statistical Software, Kremelberg, D., Ed., Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2011, ch. 4, pp. 119–204. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483385655

Statistics, STATA, and Other Statistical Software, Kremelberg, D., Ed., Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2011, ch. 4, pp. 119–204. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483385655World Health Organization, Europe (2020) coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak, Technical guidance: mental health and COVID-19. https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-emergencies/coronavirus-covid-19/technical-guidance/mental-health-and-covid-19. Accessed August 4, 2020.

Brooke, J. and Jackson, D., Older people and COVID-19: isolation, risk and ageism, J. Clin. Nurs., 2020, vol. 29, pp. 2044–2046. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15274

Turkish Ministry of Internal Affairs, Circular on the curfew for those who are 65 years and older and those with chronic illness, 2020. https://www.icisleri.gov.tr/65-yas-ve-ustu-ile-kronik-rahatsizligi-olanlara-sokaga-cikma-yasagi-genelgesi. Accessed September 13, 2020.

Varshney, M., Parel, J.T., Raizada, N., and Sarin, S.K., Initial psychological impact of COVID-19 and its correlates in Indian community: an online (FEEL-COVID) survey, PLoS One, 2020, vol. 15, no. 5, p. e0233874. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0233874

Debreczeni, F.A. and Bailey, P.E., A systematic review and meta-analysis of subjective age and the association with cognition, subjective wellbeing, and depression, J. Gerontol., B, 2021, vol. 76, no. 3, pp. 471–482. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbaa069

Feng, Z., Jones, K., and Phillips, D.R., Social exclusion, self-rated health and depression among older people in China: evidence from a national survey of older persons, Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr., 2019, vol. 82, pp. 238–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2019.02.016

Tufan, İ., Koç, O., Dere, B., et al., Yaşlιlarιn “Sokağa Çιkma Yasağι” Üzerine Görüşleri: Telefon Anketi, Geriatrik Bilimler Dergisi, 2020, vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 51–59. https://doi.org/10.47141/geriatrik.755856

Turkish Ministry of Health, General chart of coronavirus, 2020. https://covid19.saglik.gov.tr/TR-66935/genel-koronavirus-tablosu.html#. Accessed September 13, 2020.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are indebted to two anonymous reviewers for their valuable and constructive comments. We are grateful to Prof. Dr. Hasan H. Başιbüyük (Akdeniz University) for his valuable comments on early version of the manuscript. We also thank to students of the 60+ Tazelenme University, Antalya Campus.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interests. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Statement on the welfare of humans or animals. All applicable international, national, and/or institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals were followed.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Özgün-Başıbüyük, G., Kaleli, I., Efe, M. et al. Depression Tendency Caused by Social Isolation: An Assessment on Older Adults in Turkey. Adv Gerontol 11, 298–304 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1134/S2079057021030085

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1134/S2079057021030085

SPSS

SPSS

Statistics, STATA, and Other Statistical Software, Kremelberg, D., Ed., Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2011, ch. 4, pp. 119–204.

Statistics, STATA, and Other Statistical Software, Kremelberg, D., Ed., Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2011, ch. 4, pp. 119–204.