-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Kelvin Rivera, Jeffrey Maldonado, Aixa Dones, María Betancourt, Ricardo Fernández, Miguel Colón, Nocardia cyriacigeorgica threatening an immunocompetent host; a rare case of paramediastinal abscess, Oxford Medical Case Reports, Volume 2017, Issue 12, December 2017, omx061, https://doi.org/10.1093/omcr/omx061

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

We describe a rare case of anterior paramediastnial abscess due to Nocardia cyriacigeorgica in an immunocompetent patient without pre-existing lung disease. High suspicious should be taken in those patients that failed to improve after first course of antibiotic therapy. Similarly, when suspected, isolation is crucial because of the variation in antibiotic susceptibilities among Nocardia spp. in order to provide adequate therapy to reduce associated comorbidities and mortality rate.

INTRODUCTION

Nocardia cyriacigeorgica formerly known as Nocardia complex VI is an aerobic, gram-positive, weakly acid-fast, bacteria that primarily resides in soil. It usually primarily affects immunocompromised individuals and can be categorized as acute, subacute or chronic [1, 2]. The symptoms are non-specific, typically causes fever, dyspnea and cough [2]. Mortality seems to be associated with the site of infection and reach as high as 50% [3]. The incidence of nocardial infections has increased in the last several years in the United States due to a growing population of immunocompromised patient, improved methods of pathogen isolation and molecular identification in the laboratory [3]. We describe the case of healthy patient without history of lung disease whom symptoms persisted despite course of antibiotic therapy.

CASE PRESENTATION

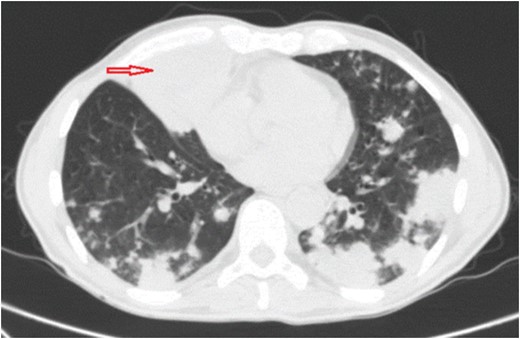

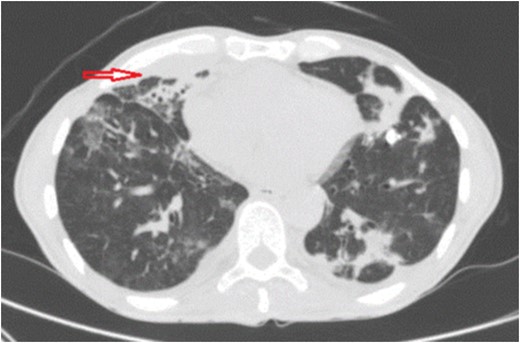

A 60-year-old man with no significant past medical history came to emergency department (ED) complaining of dry cough and fever (between 39 and 40°C) for 1 year and 6 months of evolution. During that period the patient had a significant history of night sweats and weight loss (25 pounds). He denied travels, contact with sick patients, tobacco smoking, chest or abdominal pain. Physical findings included a chronically ill, cachectic patient with bilateral basilar rhonchi on auscultation and no lymphadenopathy. Prior to ED arrival, he had an extensive outpatient work up due to persistent fever which included; chest x-ray, chest and abdomen–pelvic CT scan, CBC, blood culture, urine culture, tuberculin skin test, RPR, hepatitis B and C serology, serum complements, ANA, RF and serum immunoglobulin levels (IgA, IgG, IgM). All of these laboratories yielded normal results and imaging studies did not show lung infiltrates, mass or nodules. Additionally HIV was negative and CD4 count (980 cells/mm3) was normal. Patient continued with fever and developed dry cough 3 months after initial laboratories, reason for which chest x-ray was repeated. At that moment he was diagnosed with pneumonia and received antibiotic therapy with levofloxacin for 7 days. There was mild interval improvement, but after antibiotic therapy was completed his symptoms came back. Three weeks later after antibiotic therapy bronchoscopy for acid-fast bacilli, bacteria, fungi culture and staining was performed due to unresolved pneumonia. No organism growth or positive staining was reported neither by pathology nor by microbiology laboratory. Negative results lead to the suspicion of cryptogenic organizing pneumonia treated with prednisone 60 mg daily for ~5 weeks without success and corticosteroids were tapered down. In fact, symptoms worsened with high grade fever (40°C) and it is at this point when he arrives to ED. Patient was admitted to the hospital and chest CT scan was performed revealing a new anterior paramediastinal abscess measuring 7 cm LG × 5.8 cm AP × 6.7 cm TV with bilateral lung infiltrates (Fig. 1). The abscess was drained by interventional radiology and sample cultured on blood agar under aerobic conditions yielded white, rough and dry colonies, which presented gram-positive filamentous branched bacilli and were modified acid-fast bacilli stain-positive suggestive of Nocardia species, this was reported seven days after samples were taken. Molecular analysis by 16 S rRNA gene sequences indicated that the isolate was N. cyriacigeorgica after 2 weeks from initial samples. Trimetropin–sulfametoxazole 1020 mg daily in divided doses was initiated due to susceptibility and continued for 6 months. After 1 week there was significant improvement of symptoms and follow up imaging showed interval resolution of pulmonary infiltrates and abscess reduction (Fig. 2). The patient had continuity at outpatient clinics and have fully recovered.

Chest CT scan shows multifocal bilateral pulmonary consolidations and right anterior inferior paramediastinal abscess measuring ~7 cm LG × 5.8 cm AP × 6.7 cm TV (red arrow).

Chest CT scan shows interval resolution of paramediatinal abscess (red arrow) after percutaneous drainage and resolution of lung infiltrates after 2 weeks.

DISCUSSION

The incidence of nocardial infections is believed to be on the rise in the United States as a result of a growing population of immunocompromised host and improved methods for pathogen isolation and molecular identification [1, 4]. The number of recognized Nocardia species causing infections is also increasing [1, 4]. These factors have combined to place even greater demands on clinical microbiology laboratories to accurately identify Nocardia isolates to the species level.

Nocardia species do not typically affect immunocompetent patients, it primary affects immunocompromised individuals. Those who are immunocompetent and developed pulmonary nocardiosis usually have risk factors predisposing the disease. These risk factors most commonly includes pre-existing lung diseases as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, bronchiectasis, cystic fibrosis [2]. Additionally pulmonary nocardiosis has been reported in patients taking corticosteroid therapy, immunosuppressive therapy, transplanted patients, poorly controlled diabetes and malignancy [2]. Our patient presented a rare case of pulmonary infection with paramediastinal abscess. This atypical infectious agent, to our knowledge, is the first case report in the Caribbean in an immunocompetent patient without pre-existing lung disease or any other predisposing factors as mentioned earlier.

Most cases of pulmonary nocardiosis are not rapidly recognized because of lack of pathognomonic clinical signs, limitations of conventional biochemical tests for slow-growing bacteria, and the presence of commensal flora on culture [5]. Moreover, unless there is a high index of clinical suspicion, the diagnosis of pulmonary nocardiosis may be challenging [3]. In a retrospective study, 20% of Nocardia species isolates were found not to be associated with the clinical disease [6]. However, their presence should suggest a careful evaluation of clinical symptoms to avoid underdiagnosed nocardiosis since it has a high mortality rate if not adequately treated. High mortality rates associated to nocardiosis could be the difficulty in identifying the strain responsible for the infection on a timely fashion. Since Nocardia spp. contains many strains and has slow growth rates, the isolation and susceptibility process takes too much time, therefore, laboratories should be notified if suspected nocardial infection because most routine fluid or tissue cultures are discarded at 48–72 h [3]. Accurate and timely identification of nocardia is important because the pathogenic potential between species varies and because the species identity provides a critical guide for physicians in the choice of targeted therapy [3]. Furthermore, all species shows different patterns in their responses to treatment [7].

The fact that N. cyriacigeorgica was formerly known as Nocardia complex VI which has been identified in the southern and eastern United States including Canada suggests that N. cyriacigeorgica might actually be distributed across all of North America [3]. This rise concern among the immunocompetent population as for the health professionals to be aware of it existence and pathogenicity. Likewise, clinical microbiology laboratories need to adapt laboratory protocols for its specific identification.

The importance of this case relies mostly on the delayed of adequate therapy due to an underdiagnosed infectious process. This implies that pulmonary nocardiosis should be suspected not only in the immunocompromised host but also in the immunocompetent patients without pre-existing lung disease who failed initial therapy for pneumonic process.

Conflict of Interest STATEMENT

There is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of this case.

FUNDING

This case report did not receive any specific grant form any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-profit sector.

CONSENT

A written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of the case.