-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Pascal Obong Bessong, Emanuel Nyathi, Tjale Cloupas Mahopo, Vhonani Netshandama, MAL-ED South Africa, Development of the Dzimauli Community in Vhembe District, Limpopo Province of South Africa, for the MAL-ED Cohort Study, Clinical Infectious Diseases, Volume 59, Issue suppl_4, November 2014, Pages S317–S324, https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciu418

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

The Dzimauli community is located in the Vhembe district in the northern part of Limpopo Province, South Africa. The district is bordered by Botswana and Zimbabwe to the north and Mozambique to the East. The study site population is entirely blacks and 53% female, with a mean household size of 6 persons. Through a consultative process, we engaged and prepared the Dzimauli, a community of low socioeconomic status, to participate in a longitudinal, observational study. In addition to contributing to the objectives of The Etiology, Risk Factors and Interactions of Enteric Infections and Malnutrition and the Consequences for Child Health and Development (MAL-ED) cohort study, we established a high degree of public trust and understanding of scientific research within the community and its leaders. This has resulted in creating an entirely new site suitable for potential future field-based intervention studies based on an improved understanding of the factors influencing child health in this community.

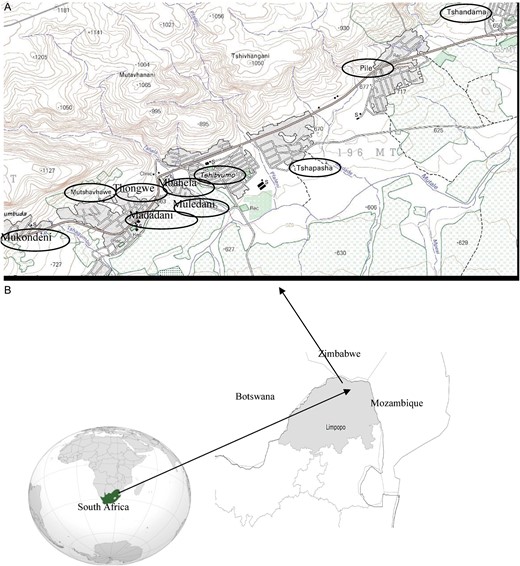

In 2011, the population of South Africa was 51.7 million [1], of whom 5.4 million live in the Limpopo province. The Limpopo province unemployment rate is 39%, compared with the national rate of 30% [1]. Approximately 17% of the inhabitants of the province do not have any formal education [1]. The province is bordered to the east by Mozambique, to the north by Zimbabwe, and to the northwest by Botswana (Figure 1). The health data available for Limpopo province indicate a tuberculosis rate of 407/100 000 population, a malaria rate of 45/100 000, a diarrheal incidence in children <5 years old of 180/1000, and a mortality rate of 40.6/1000 live births in the same age group [2]. In 2011, the estimated nationwide prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection was 22%, and was based on a prenatal seroprevalence survey [3].

A, Study area of Dzimauli comprises the villages (circled) along the main road axis and spans a distance of about 20 km. Dzimauli is about 45 km north of the University of Venda in the Vhembe district capital of Thohoyandou. B, Situational representation of the MAL-ED field site in the Limpopo province of South Africa.

Inhabitants of Limpopo are employed by public sector institutions and the mining, trade, and agricultural sectors. Although the land is fertile and well suited for agriculture, a large portion of it is controlled by tribal authorities, which hinders large-scale development. Nevertheless, there are opportunities for developing viable, sustainable agricultural projects in Limpopo. Commercial and subsistence farming occur, and animals are hunted for protein.

The Interactions of Malnutrition and Enteric Infections: Consequences for Child Health and Development study (MAL-ED), has established a network of 8 sites that focuses on studying populations with a high prevalence of malnutrition and enteric infections. The investigators at these 8 sites, including those in Bangladesh, Brazil, India, Nepal, Pakistan, Peru, South Africa, and Tanzania, and their colleagues in the United States are conducting comprehensive studies, using shared and harmonized protocols, to identify and characterize the factors associated with a child's risk of enteric infection, chronic diarrhea, and malnutrition, as well with impaired gut function, vaccine response, and cognitive and physical development. These studies will elucidate some of the complex relationships among these factors, leading to more targeted, cost-effective interventions that will further reduce the burden of disease for those living in poverty.

The University of Venda in Thohoyandou, Limpopo province, is the implementing partner for the MAL-ED study in South Africa, with the University of Virginia as the US partner. Before MAL-ED, collaborative engagements included research on enteropathogens, determining health indicators for rural communities and human capacity development in the form of student and staff exchanges. The teams at both institutions visited several communities and met with local health and civil authorities, sometimes more than once, to identify the most appropriate site for the study. The main issues considered included socioeconomic status (SES), possibility of recruiting an adequate number of participants during a 2-year period, and reasonable proximity to the University of Venda for time-dependent microbiological analyses and preservation of biospecimens. Training of field surveillance and laboratory personnel (and retraining when required) was provided by the field and laboratory coordinator at the University of Virginia. The study protocol and subsequent modifications were reviewed and approved by the review boards of the University of Venda and the University of Virginia. Visits were made at different times by Virginia collaborators to support site activities. The study team, geography, demography, social, and economic features of Dzimauli, the MAL-ED cohort study field site in the Limpopo province of South Africa, are described in this article. We also present the preparatory process used to engage the Dzimauli community before the initiation of the study protocol. Table 1 provides a summary of some key provincial and national demographic and health data.

Major Socioeconomic and Health Indicators for Study Site (Limpopo Province) and South Africa

| Feature . | Limpopo Province . | South Africa . |

|---|---|---|

| Population density, per km2 | 43 | 43 |

| Rural, % | 87 | 43 |

| Female, % | 54 | 52 |

| Mean family size | 3.7 | 3.4 |

| Mean expectancy, y | 56 | 52 |

| Access to clean water, % | 84 | 89 |

| Access to electricity, % | 87 | 84 |

| Access to improved toilet/sanitation, % | 97 | 93 |

| Mortality in children <5 y old, deaths/1000 live births | 56 | 57 |

| Diarrhea incidence in children <5 y old, cases/1000 live births | 180 | 118 |

| HIV prevalence, % | 22 | 30 |

| Tuberculosis incidence, cases/100 000 persons | 407 | 773 |

| Malaria incidence, cases/100 000 persons | 124 | 143 |

| Per capita GDP, $ | … | 11 035 |

| Feature . | Limpopo Province . | South Africa . |

|---|---|---|

| Population density, per km2 | 43 | 43 |

| Rural, % | 87 | 43 |

| Female, % | 54 | 52 |

| Mean family size | 3.7 | 3.4 |

| Mean expectancy, y | 56 | 52 |

| Access to clean water, % | 84 | 89 |

| Access to electricity, % | 87 | 84 |

| Access to improved toilet/sanitation, % | 97 | 93 |

| Mortality in children <5 y old, deaths/1000 live births | 56 | 57 |

| Diarrhea incidence in children <5 y old, cases/1000 live births | 180 | 118 |

| HIV prevalence, % | 22 | 30 |

| Tuberculosis incidence, cases/100 000 persons | 407 | 773 |

| Malaria incidence, cases/100 000 persons | 124 | 143 |

| Per capita GDP, $ | … | 11 035 |

Abbreviations: GDP, gross domestic product; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

Major Socioeconomic and Health Indicators for Study Site (Limpopo Province) and South Africa

| Feature . | Limpopo Province . | South Africa . |

|---|---|---|

| Population density, per km2 | 43 | 43 |

| Rural, % | 87 | 43 |

| Female, % | 54 | 52 |

| Mean family size | 3.7 | 3.4 |

| Mean expectancy, y | 56 | 52 |

| Access to clean water, % | 84 | 89 |

| Access to electricity, % | 87 | 84 |

| Access to improved toilet/sanitation, % | 97 | 93 |

| Mortality in children <5 y old, deaths/1000 live births | 56 | 57 |

| Diarrhea incidence in children <5 y old, cases/1000 live births | 180 | 118 |

| HIV prevalence, % | 22 | 30 |

| Tuberculosis incidence, cases/100 000 persons | 407 | 773 |

| Malaria incidence, cases/100 000 persons | 124 | 143 |

| Per capita GDP, $ | … | 11 035 |

| Feature . | Limpopo Province . | South Africa . |

|---|---|---|

| Population density, per km2 | 43 | 43 |

| Rural, % | 87 | 43 |

| Female, % | 54 | 52 |

| Mean family size | 3.7 | 3.4 |

| Mean expectancy, y | 56 | 52 |

| Access to clean water, % | 84 | 89 |

| Access to electricity, % | 87 | 84 |

| Access to improved toilet/sanitation, % | 97 | 93 |

| Mortality in children <5 y old, deaths/1000 live births | 56 | 57 |

| Diarrhea incidence in children <5 y old, cases/1000 live births | 180 | 118 |

| HIV prevalence, % | 22 | 30 |

| Tuberculosis incidence, cases/100 000 persons | 407 | 773 |

| Malaria incidence, cases/100 000 persons | 124 | 143 |

| Per capita GDP, $ | … | 11 035 |

Abbreviations: GDP, gross domestic product; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

SITE PREPARATION PROCESS

Composition of the Study Team

The initial study team involved with site preparation comprised the site principal investigator (PhD in microbiology), a study coordinator (MSc in microbiology), a community engagement expert (PhD in nursing), a study physician (MBBS), a laboratory manager (PhD in microbiology), a data manager (BSc), and 4 field workers (BSc or high school diploma holders). Before commencement of the study, the following personnel were added: a study nurse (nursing diploma), a laboratory technologist (national diploma in microbiology), 4 nutritionists (BSc in public health nutrition), 2 psychologists (1 PhD and 1 MSc in clinical psychology), 5 auxiliary nurses, 4 assistant nutritionists, 2 assistant psychologists, a project administrator, 2 data clerks, and a driver. As the number of study subjects and workload increased, more field staff and laboratory assistants and another driver were recruited. At the peak of the study, the site had 42 personnel size. The initial training of psychology and nutrition staff was provided on site by delegated experts of the cognitive development and nutrition subcommittees of MAL-ED respectively. The data manager received 2 rounds of training during centralized training sessions organized by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health in the United States. Follow-up guidance was provided by telephone or during subcommittee conference calls.

Selection of the Study Population

To meet the objectives of the MAL-ED cohort study, visits were made to several locations in the Limpopo province to identify an appropriate study population. Factors considered in the selection of the site included population and birth rate, accessibility to the community and its members, proximity to the MAL-ED South Africa study staff located at the University of Venda in Limpopo, and the socioeconomic profile of the population. After an evaluation of these factors, the Dzimuali community was selected as a representative and suitable field site for the MAL-ED study.

Geography of the Dzimauli Community

The Dzimauli community comprises 13 linear settlements (ie, villages) that are adjacent to each other, and some of these settlements lack any clear demarcation boundaries between them. The villages include Mbahela, Mukondeni, Thongwe, Madadani, Muledani, Matshavhawe, Tshibvumo, Tshapasha, Pile, Tshandama, Mutodani, Tshitopeni, and Tshagwa. Dzimauli is generally a hilly rural area with shrublike vegetation. It is about 45 km from Thohoyandou the nearest large town and capital of the Vhembe district. The roads leading to the area are filled with potholes and muddy during the summer months (ie, rainy period) and dusty during the winter months. During summer, most of the roads within the area are eroded and impassable by car. A feeding program supported by the US Agency for International Development that provides lunch for primary school children in one of the villages (Tshibvumo). The mean monthly high temperatures range from 25°C to 31°C, to a low mean temperature of between 9°C and 20°C; July is the coldest month. Rainfall is highly seasonal, with 95% occurring between October and March. Generally, the Limpopo province where Dzimauli is located is the warmest region in the country.

Demographic, Socioeconomic, and Health Indicators of the MAL-ED Dzimauli Study Cohort

The Dzimauli area has an estimated population of 9000. Before the start of the MAL-ED study, a pilot SES survey was conducted between September and October 2009 by project staff according to MAL-ED study protocol using 100 randomly selected households in Dzimauli. The door-to-door survey was done by paper questionnaire administration in Tshivenda, the commonly used local language, and in English whenever needed.

Results from the pilot SES survey indicated the mean age of mothers was 31 years, and the mean age at first pregnancy 20 years. There was a mean of 2.5 live births for the pilot survey population. In addition, the mean duration of schooling was 10 years. Sixty-eight percent of the households surveyed had a monthly income of ≤$62. Table 2 includes the results of the pilot SES survey of the Dzimauli community.

SES Data From Pilot Census and Baseline of Cohort Study

| Variable . | Pilot SES Census (n = 100) . | Baseline SES of Cohort (n = 244) . |

|---|---|---|

| Age of mother, mean (range), y | 30.5 (19–48) | 27.8 (17–46) |

| Age at first pregnancy, mean (range), y | 19.8 (14–28) | 19.8 (12–29) |

| Live births, mean (range), No. | 2.5 (1–7) | 2.4 (1–7) |

| Home deliveries, % | … | 1 |

| Pre- and postnatal care, % | … | 65 |

| Duration family has lived in the house, % | ||

| <1 y | 3 | … |

| 1–5 y | 5 | … |

| 5–10 y | 11 | … |

| 10–20 y | 24 | 70a for >10 y |

| >20 y | 57 | 50a |

| Households with >5 rooms, % | 38 | 45 |

| Rooms for sleeping, mean (range), No. | 2.8 (1–9) | 2.7 (1–6) |

| Persons who usually sleep in household, mean (range), No. | 5.7 (1–14) | 6.1 (2–15) |

| Composition of roof, % | ||

| Thatch | 4 | 8 |

| Metal | 85 | 86 |

| Wood | 1 | 0.4 |

| Tiles | 1 | 4 |

| Slate | 10 | 1 |

| Other | 0 | 0.4 |

| Composition of floor, % | ||

| Earth or sand | 4 | 8 |

| Wood | 0 | 0.4 |

| Ceramic | 3 | 3 |

| Cement/concrete | 93 | 89 |

| Composition of walls, % | ||

| Mud/sand | 7 | 11 |

| Cement/concrete | 61 | 86 |

| Stone w/lime | 1 | 0.4 |

| Brick | 31 | 3 |

| Separate room for cooking, % | 74 | 76 |

| Inside house | 55 | 48 |

| Outside house | 15 | 19 |

| Both inside and outside house | 30 | 33 |

| Type of cooking stove used, % | ||

| Open fire | 67 | 61 |

| Electric heaters | 11 | 26 |

| Household heated by any means, % | ||

| Yes | 7 | 43 |

| Wood | 29 | 78 |

| Electricity | 71 | 22 |

| Households with domestic workers, % | 2 | 6 |

| Households with electricity (ever), % | 60 | 85 |

| Main source of drinking water, % | ||

| Piped into dwelling | 0 | 2 |

| Piped to yard/plot | 57 | 51 |

| Public tap/stand pipe | 6 | 31 |

| Tube well/borehole | 1 | 2 |

| Surface water (river/dam/lake/pond/ stream/canal/irrigation canal) | 35 | 15 |

| Unprotected spring | 1 | 0 |

| Households that treat drinking water, % | 19 | 12 |

| Water treatment at household, % | ||

| Stand/settle | 70 | 11 |

| Add bleach/chlorine | 23 | 46 |

| Boil | 5 | 29 |

| Other | 2 | 14 |

| Type of toilet facility, % | ||

| No facility/bush/field/bucket toilet | 1 | 2.0 |

| Pit latrine without flush | 94 | 95.1 |

| Flush to piped sewer system | 0 | 0.8 |

| Flush to septic tank | 1 | 0.4 |

| Flush to somewhere else | 0 | 0.4 |

| Other | 4 | 1.2 |

| Wash hand after helping child defecate, % | ||

| Always | 72 | 3 |

| Sometimes | 17 | 6 |

| Rarely | 5 | 29 |

| Never | 5 | 62 |

| Educational level of mother, mean (range), y | 9.8 (4–15 y) | 9.0 (1–15)b |

| Monthly household income, % | ||

| ≤$62 | 68 | 3 |

| $62–$123 | 14 | 24 |

| $123–$185 | 8 | 21 |

| >$185 | 10 | 53 |

| Variable . | Pilot SES Census (n = 100) . | Baseline SES of Cohort (n = 244) . |

|---|---|---|

| Age of mother, mean (range), y | 30.5 (19–48) | 27.8 (17–46) |

| Age at first pregnancy, mean (range), y | 19.8 (14–28) | 19.8 (12–29) |

| Live births, mean (range), No. | 2.5 (1–7) | 2.4 (1–7) |

| Home deliveries, % | … | 1 |

| Pre- and postnatal care, % | … | 65 |

| Duration family has lived in the house, % | ||

| <1 y | 3 | … |

| 1–5 y | 5 | … |

| 5–10 y | 11 | … |

| 10–20 y | 24 | 70a for >10 y |

| >20 y | 57 | 50a |

| Households with >5 rooms, % | 38 | 45 |

| Rooms for sleeping, mean (range), No. | 2.8 (1–9) | 2.7 (1–6) |

| Persons who usually sleep in household, mean (range), No. | 5.7 (1–14) | 6.1 (2–15) |

| Composition of roof, % | ||

| Thatch | 4 | 8 |

| Metal | 85 | 86 |

| Wood | 1 | 0.4 |

| Tiles | 1 | 4 |

| Slate | 10 | 1 |

| Other | 0 | 0.4 |

| Composition of floor, % | ||

| Earth or sand | 4 | 8 |

| Wood | 0 | 0.4 |

| Ceramic | 3 | 3 |

| Cement/concrete | 93 | 89 |

| Composition of walls, % | ||

| Mud/sand | 7 | 11 |

| Cement/concrete | 61 | 86 |

| Stone w/lime | 1 | 0.4 |

| Brick | 31 | 3 |

| Separate room for cooking, % | 74 | 76 |

| Inside house | 55 | 48 |

| Outside house | 15 | 19 |

| Both inside and outside house | 30 | 33 |

| Type of cooking stove used, % | ||

| Open fire | 67 | 61 |

| Electric heaters | 11 | 26 |

| Household heated by any means, % | ||

| Yes | 7 | 43 |

| Wood | 29 | 78 |

| Electricity | 71 | 22 |

| Households with domestic workers, % | 2 | 6 |

| Households with electricity (ever), % | 60 | 85 |

| Main source of drinking water, % | ||

| Piped into dwelling | 0 | 2 |

| Piped to yard/plot | 57 | 51 |

| Public tap/stand pipe | 6 | 31 |

| Tube well/borehole | 1 | 2 |

| Surface water (river/dam/lake/pond/ stream/canal/irrigation canal) | 35 | 15 |

| Unprotected spring | 1 | 0 |

| Households that treat drinking water, % | 19 | 12 |

| Water treatment at household, % | ||

| Stand/settle | 70 | 11 |

| Add bleach/chlorine | 23 | 46 |

| Boil | 5 | 29 |

| Other | 2 | 14 |

| Type of toilet facility, % | ||

| No facility/bush/field/bucket toilet | 1 | 2.0 |

| Pit latrine without flush | 94 | 95.1 |

| Flush to piped sewer system | 0 | 0.8 |

| Flush to septic tank | 1 | 0.4 |

| Flush to somewhere else | 0 | 0.4 |

| Other | 4 | 1.2 |

| Wash hand after helping child defecate, % | ||

| Always | 72 | 3 |

| Sometimes | 17 | 6 |

| Rarely | 5 | 29 |

| Never | 5 | 62 |

| Educational level of mother, mean (range), y | 9.8 (4–15 y) | 9.0 (1–15)b |

| Monthly household income, % | ||

| ≤$62 | 68 | 3 |

| $62–$123 | 14 | 24 |

| $123–$185 | 8 | 21 |

| >$185 | 10 | 53 |

Abbreviation: SES, socioeconomic status.

a 70% for >10 and 50% for >20 years.

b At least 1 year for 78%.

SES Data From Pilot Census and Baseline of Cohort Study

| Variable . | Pilot SES Census (n = 100) . | Baseline SES of Cohort (n = 244) . |

|---|---|---|

| Age of mother, mean (range), y | 30.5 (19–48) | 27.8 (17–46) |

| Age at first pregnancy, mean (range), y | 19.8 (14–28) | 19.8 (12–29) |

| Live births, mean (range), No. | 2.5 (1–7) | 2.4 (1–7) |

| Home deliveries, % | … | 1 |

| Pre- and postnatal care, % | … | 65 |

| Duration family has lived in the house, % | ||

| <1 y | 3 | … |

| 1–5 y | 5 | … |

| 5–10 y | 11 | … |

| 10–20 y | 24 | 70a for >10 y |

| >20 y | 57 | 50a |

| Households with >5 rooms, % | 38 | 45 |

| Rooms for sleeping, mean (range), No. | 2.8 (1–9) | 2.7 (1–6) |

| Persons who usually sleep in household, mean (range), No. | 5.7 (1–14) | 6.1 (2–15) |

| Composition of roof, % | ||

| Thatch | 4 | 8 |

| Metal | 85 | 86 |

| Wood | 1 | 0.4 |

| Tiles | 1 | 4 |

| Slate | 10 | 1 |

| Other | 0 | 0.4 |

| Composition of floor, % | ||

| Earth or sand | 4 | 8 |

| Wood | 0 | 0.4 |

| Ceramic | 3 | 3 |

| Cement/concrete | 93 | 89 |

| Composition of walls, % | ||

| Mud/sand | 7 | 11 |

| Cement/concrete | 61 | 86 |

| Stone w/lime | 1 | 0.4 |

| Brick | 31 | 3 |

| Separate room for cooking, % | 74 | 76 |

| Inside house | 55 | 48 |

| Outside house | 15 | 19 |

| Both inside and outside house | 30 | 33 |

| Type of cooking stove used, % | ||

| Open fire | 67 | 61 |

| Electric heaters | 11 | 26 |

| Household heated by any means, % | ||

| Yes | 7 | 43 |

| Wood | 29 | 78 |

| Electricity | 71 | 22 |

| Households with domestic workers, % | 2 | 6 |

| Households with electricity (ever), % | 60 | 85 |

| Main source of drinking water, % | ||

| Piped into dwelling | 0 | 2 |

| Piped to yard/plot | 57 | 51 |

| Public tap/stand pipe | 6 | 31 |

| Tube well/borehole | 1 | 2 |

| Surface water (river/dam/lake/pond/ stream/canal/irrigation canal) | 35 | 15 |

| Unprotected spring | 1 | 0 |

| Households that treat drinking water, % | 19 | 12 |

| Water treatment at household, % | ||

| Stand/settle | 70 | 11 |

| Add bleach/chlorine | 23 | 46 |

| Boil | 5 | 29 |

| Other | 2 | 14 |

| Type of toilet facility, % | ||

| No facility/bush/field/bucket toilet | 1 | 2.0 |

| Pit latrine without flush | 94 | 95.1 |

| Flush to piped sewer system | 0 | 0.8 |

| Flush to septic tank | 1 | 0.4 |

| Flush to somewhere else | 0 | 0.4 |

| Other | 4 | 1.2 |

| Wash hand after helping child defecate, % | ||

| Always | 72 | 3 |

| Sometimes | 17 | 6 |

| Rarely | 5 | 29 |

| Never | 5 | 62 |

| Educational level of mother, mean (range), y | 9.8 (4–15 y) | 9.0 (1–15)b |

| Monthly household income, % | ||

| ≤$62 | 68 | 3 |

| $62–$123 | 14 | 24 |

| $123–$185 | 8 | 21 |

| >$185 | 10 | 53 |

| Variable . | Pilot SES Census (n = 100) . | Baseline SES of Cohort (n = 244) . |

|---|---|---|

| Age of mother, mean (range), y | 30.5 (19–48) | 27.8 (17–46) |

| Age at first pregnancy, mean (range), y | 19.8 (14–28) | 19.8 (12–29) |

| Live births, mean (range), No. | 2.5 (1–7) | 2.4 (1–7) |

| Home deliveries, % | … | 1 |

| Pre- and postnatal care, % | … | 65 |

| Duration family has lived in the house, % | ||

| <1 y | 3 | … |

| 1–5 y | 5 | … |

| 5–10 y | 11 | … |

| 10–20 y | 24 | 70a for >10 y |

| >20 y | 57 | 50a |

| Households with >5 rooms, % | 38 | 45 |

| Rooms for sleeping, mean (range), No. | 2.8 (1–9) | 2.7 (1–6) |

| Persons who usually sleep in household, mean (range), No. | 5.7 (1–14) | 6.1 (2–15) |

| Composition of roof, % | ||

| Thatch | 4 | 8 |

| Metal | 85 | 86 |

| Wood | 1 | 0.4 |

| Tiles | 1 | 4 |

| Slate | 10 | 1 |

| Other | 0 | 0.4 |

| Composition of floor, % | ||

| Earth or sand | 4 | 8 |

| Wood | 0 | 0.4 |

| Ceramic | 3 | 3 |

| Cement/concrete | 93 | 89 |

| Composition of walls, % | ||

| Mud/sand | 7 | 11 |

| Cement/concrete | 61 | 86 |

| Stone w/lime | 1 | 0.4 |

| Brick | 31 | 3 |

| Separate room for cooking, % | 74 | 76 |

| Inside house | 55 | 48 |

| Outside house | 15 | 19 |

| Both inside and outside house | 30 | 33 |

| Type of cooking stove used, % | ||

| Open fire | 67 | 61 |

| Electric heaters | 11 | 26 |

| Household heated by any means, % | ||

| Yes | 7 | 43 |

| Wood | 29 | 78 |

| Electricity | 71 | 22 |

| Households with domestic workers, % | 2 | 6 |

| Households with electricity (ever), % | 60 | 85 |

| Main source of drinking water, % | ||

| Piped into dwelling | 0 | 2 |

| Piped to yard/plot | 57 | 51 |

| Public tap/stand pipe | 6 | 31 |

| Tube well/borehole | 1 | 2 |

| Surface water (river/dam/lake/pond/ stream/canal/irrigation canal) | 35 | 15 |

| Unprotected spring | 1 | 0 |

| Households that treat drinking water, % | 19 | 12 |

| Water treatment at household, % | ||

| Stand/settle | 70 | 11 |

| Add bleach/chlorine | 23 | 46 |

| Boil | 5 | 29 |

| Other | 2 | 14 |

| Type of toilet facility, % | ||

| No facility/bush/field/bucket toilet | 1 | 2.0 |

| Pit latrine without flush | 94 | 95.1 |

| Flush to piped sewer system | 0 | 0.8 |

| Flush to septic tank | 1 | 0.4 |

| Flush to somewhere else | 0 | 0.4 |

| Other | 4 | 1.2 |

| Wash hand after helping child defecate, % | ||

| Always | 72 | 3 |

| Sometimes | 17 | 6 |

| Rarely | 5 | 29 |

| Never | 5 | 62 |

| Educational level of mother, mean (range), y | 9.8 (4–15 y) | 9.0 (1–15)b |

| Monthly household income, % | ||

| ≤$62 | 68 | 3 |

| $62–$123 | 14 | 24 |

| $123–$185 | 8 | 21 |

| >$185 | 10 | 53 |

Abbreviation: SES, socioeconomic status.

a 70% for >10 and 50% for >20 years.

b At least 1 year for 78%.

On enrollment in the MAL-ED study, an SES survey was conducted for the child's household. A total of 244 households were surveyed between November 2009 and February 2012. Table 2 includes the results from the pilot and cohort SES surveys. Within the study cohort, the mean age of mothers at recruitment was 28 years, and the mean duration of schooling received was 9 years. About 22% of the mothers had received ≥1 year of formal education, compared with 17% in the Limpopo province's general population. The mean age at first pregnancy was 19 years, with a mean of 2.4 live births. The vast majority of the participants use the Tshivenda language, with smaller numbers using Xitsonga and IsiZulu.

Furthermore, most of the SES survey inhabitants in the study cohort were engaged in subsistence farming, minor trading, or government agency work in the nearby towns. More than 70% of Dzimauli residents have lived in the study area for >10 years, and about 50% for >20 years. Most houses (85%) have cement or concrete walls, and about 45% have 5–7 rooms. Household size, defined as the number who spend most of their nights in the house, ranges from 2 to 15 persons. Only 6% of the surveyed households employ a domestic worker and is not a common practice. Although >80% of homes have electricity, 78% use wood to heat the home. Slightly more than half of cohort households (51%) have water piped into the yard or plot, compared with 86% for the entire Limpopo province [1]. Only 12% of households surveyed within the cohort treat their drinking water by any means, and of these 46% add bleach or chlorine to the water. A majority of households (95%) use pit latrines without a flushing system. Approximately 61% of the participants cook with open fires, and 48% cook inside the home.

Information compiled from the local health clinic (located in Thongwe, one of the study villages) indicates that only 1% of mothers give birth at home, the rest give birth at the local clinic or in any other health care center outside the area. It is important to note that there is an integrated health care center about 20 km from Dzimauli and a hospital about 40 km away. We observed that most young mothers prefer to give birth where their older relatives live, generally outside the study area. However, they are expected to report to their local clinic within 2 weeks of delivery to be legible for child support benefits. Our baseline SES cohort survey also indicated a 1% rate of home delivery, but a 65% rate of use for prenatal and postnatal care services. Generally, there is an overall high rate of childbirth at a health facility in South Africa, even in rural areas because since there is ≥1 clinic with a maternity service for every 10 000 population. There are no official figures for immunization coverage, stunting, or anemia for the Dzimauli area. However, district immunization coverage for infants <1 year old is 98%, above the national mean of 90%. On the other hand, a relatively high rate of stunting (18%) is present in children in Limpopo [4]. In addition, a recent study by Heckman and colleagues [5] suggests a high rate of anemia (75%) in young children in Vhembe district. There are no data on HIV prevalence in the Dzimauli community, but the district HIV prevalence in 2009 was about 14% [3], with a mother-to-child transmission rate estimated at 3.5% [6]. Because the goal was to enroll about 300 children, the number of participants with HIV in the study cohort was expected to be very low to influence the overall study outcomes in terms of child growth, cognitive development, and vaccine response. As a result, the mothers and children were not tested for HIV.

Data from the SES survey conducted before enrollment of study participants was comparable to the baseline MAL-ED SES data for most of the indicators measured. Of note, however, is the higher proportion of MAL-ED participants (65%) who reported making use of prenatal and postnatal services, compared with none in the pre–MAL-ED survey. In addition, personal hygienic practices were poorer in the MAL-ED participants than was observed in the pre–MAL-ED survey.

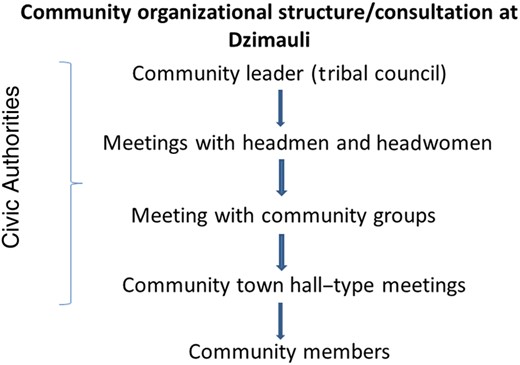

Engaging the Participation of the Dzimauli Community

After identifying Dzimauli as an appropriate field site for MAL-ED, a critical step was to engage the traditional and civil authorities within the community before attempting to interact with community members and implementing the study. Within the Dzimauli community, the traditional leadership is comprised of 2 levels: a chief who oversees all the villages in the Dzimauli community, and a headman who oversees a particular village. Because the Dzimauli community had no prior experience with clinical research studies, our meetings with these community leaders included the following topics: the MAL-ED study objectives; requirements of subject participation; expected study outcomes; bioethical considerations of human subject research; and the potential benefits to participants, community, and country. The MAL-ED study was formally begun only after an endorsement was received from community leaders.

The MAL-ED South African study staff also engaged the support of several community groups. For example, meetings were held with local groups of female elders, home-based care groups, and community development workers. Meetings were also held with the authorities of the only clinic and district health managers to introduce the purpose of the MAL-ED study and discuss possible collaborations with their staff. Figure 2 illustrates the community engagement process before study participant recruitment. In preparation for meeting with Dzimauli community members, a brochure describing the MAL-ED study was developed in both Tshivenda (the local language) and English and was distributed widely in the community.

Flow diagram of the consultative process used to engage the Dzimauli community in the MAL-ED study. Approval from traditional and civic leaders was essential before discussion with community members and before contacting inhabitants for subsequent recruitment into the study. Regular feedback meetings with study participants enhanced compliance with study protocols and improved the quality of the data obtained.

Recruitment of Study Participants in Dzimauli

Before the active recruitment of study participants, several large meetings were held in each village that was located within the study area to inform and sensitize inhabitants about the study. These town hall–type meetings were held at least once for each village on a Saturday or Sunday morning, starting between 7 and 8 am and lasting about 2 hours. The venue was either in the open under a tree or in a local school or church. Sometimes, following the advice of the village headman or headwoman, the meeting was held just after a civic gathering to ensure high attendance. Participants in these meetings included male and female villagers of all ages, married and unmarried. There were no exclusion criteria. Weekend and morning meetings were preferred to enable access to as many villagers as possible. Meeting deliberations took place in Tshivenda. The South Africa MAL-ED study staff presented on the purpose of the MAL-ED study, the consenting process to enroll, what would be required from enrolled participants, the duration of participation, and study participants' rights and protection. These presentations were followed by question-and-answer sessions with the villagers. Incentives were not provided to encourage attendance at these meetings.

After the meetings held with villages in Dzimauli, study participants were recruited from the following 10 villages: Mbahela, Mukondeni, Thongwe, Madadani, Muledani, Matshavhawe, Tshibvumo, Tshapasha, Pile, and Tshandama. The distance between the nearest and the farthest village in the study site is about 20 km. The villages were selected because they had a relatively high number of households and were in close proximity.

Identification of potential study participants from within the 10 villages was accomplished using 2 approaches from November 2009 to February 2012. First, every pregnant woman in the third trimester of pregnancy according to clinic records was identified in each village by MAL-ED field workers, most of whom live in the study area. These pregnant women were contacted weekly by in-person visits or by telephone for likely study participation. Soon after delivery, mothers interested in enrolling in the study were contacted and provided with an informed consent form. The procedure followed for obtaining informed consent was defined by the standard operating procedures of the MAL-ED Network, and approved by all relevant institutional review boards associated with the University of Venda (South Africa) and the University of Virginia (United States). Second, MAL-ED study field workers in collaboration with the local health clinic staff met with expectant mothers during prenatal clinic visits and discussed their potential enrollment into the study. These 2 recruitment approaches were followed until a total of 314 participants were recruited for the study.

Additional meetings and listening sessions were held with mothers from each village enrolled in the study to solicit their feedback and answer their questions about the study. On average once in 6 months, on a weekend, mothers meet in an agreed-on venue. The location chosen was usually one that would allow easy congregation of mothers from 2 or 3 villages. Transportation was provided for all mothers who needed it, and lunch was served at the close of the session. These meetings also served as venues for the continuous education of the participants about the MAL-ED study protocol. Although only MAL-ED mothers were invited, the husbands of some of them participated, as well as men and women not involved with the study, although in smaller numbers.

A challenge to maintaining participants in the study stemmed from the significant mobility among the young mothers of study subjects who moved in and out of the community in search of work or, education or to accompany their spouses. We learned early on to maintain contact with these women while they were temporarily away from the Dzimauli community, to minimize future study dropouts.

Data Collection

Surveillance for illnesses and symptoms (eg, diarrhea, vomiting, fever, and acute lower respiratory tract infections), vaccine history, and feeding patterns was conducted twice a week by auxiliary nurses and other trained staff. During these visits, monthly stool samples were collected when due and samples when diarrhea was present. The collection of urine for lactulose-mannitol testing required about 5 hours, and this was usually done on a day when the child had no other assessments. Monthly anthropometric measurements were taken by nutritionists supported by trained assistants. Dietary and follow-up socioeconomic data were collected by nutritionists. Each field staff member for surveillance, anthropometrics, and stool collection was assigned a specific number of participants in a particular village and the assignment maintained as much as possible throughout the study duration. This allowed for the cultivation of a good rapport between the field staff and study subjects. Blood samples were collected at 7 and 15 month of age by a pediatric phlebotomist or study physician, and cognitive assessments were performed by psychologists supported by trained assistants.

All data collection was done at home, except the Bailey Scales of Infant Development (BSID-III), which was done in an appropriate dedicated room in the local clinic, according to the MAL-ED protocol. Blood samples were also preferably collected at the local clinic, although some mothers preferred collection at home. Study subjects were batched for blood collection, whenever the collection window permitted, so that samples can be transported as soon as possible to the laboratory 45 km away. Stool samples were initially preserved in the field ≤2 hours after being produced and transported to the laboratory within 6 hours.

Field work was conducted on weekends or public holidays whenever necessary. For example, if a participant has indicated the intention to travel out of the study area for few days, scheduled assessments that would coincide with the absence were preferably done earlier. Moreover, whenever a mother reported a case of diarrhea, usually by a text message to field staff, a stool sample would then be collected and one of the drivers notified. At least 1 laboratory worker was on standby after working hours and on weekends to receive samples. A reasonable amount of sample collection material and case report forms was continuously kept in the local clinic for use by field staff. A refrigerator was also installed at the local clinic for short-term storage of samples pending transportation to the laboratory.

The site principle investigator or study coordinator met with field staff weekly in the community hall to review all components of the study for that week, address challenges faced by field staff, and provide retraining when necessary. Several challenges were encountered in data collection. A major challenge was the relatively high mobility of younger mothers out of the study area. We continued following up those who relocated not too far from the study area. This meant extra planning in reassigning staff and cost of transportation, but it was important particularly if the participant wanted to stay in the study and for the acquisition of complete data sets. It was also difficult to collect enough blood from some of the very young study subjects for all the anticipated tests. Although home visits were done mostly on foot, they became very challenging with the muddy and slippery roads and paths during the rainy season particularly on the slopes of the community. The study area is about 20 km long, and sometimes field staff had to trek for long distances carrying anthropometric equipment to visit homes. Some parents preferred a particular field worker or were not willing to continue providing a particular biospecimen, and these issues also had to be resolved.

CONCLUSIONS

A rural community in northeastern South Africa with a low SES was successfully prepared to participate in a longitudinal, observational, community-based study aimed at elucidating the interactions of enteric infections, malnutrition, and child growth and development. The Dzimauli community was an appropriate population for the MAL-ED study because of their demographic, socioeconomic, and health status, but also because of their receptiveness to participating in the study. However, significant challenges were faced when initiating the study, including the need to spend considerable time educating and preparing the community and its leaders on the requirements for participating in an intense longitudinal observational study and working to obtain their endorsement and support. It was crucial for the MAL-ED South African study staff to be attentive and sensitive to issues and concerns raised by the community regarding the study and possible conflicts with the community's culture and popular beliefs. In addition to periodic discussion sessions with study participants, close collaboration between the community leaders and local health personnel was essential for mobilizing community participation. Thorough explanation before recruitment and continuous education was required to improve participants’ understanding of the study objectives and procedures and their subsequent adherence to study protocols.

Notes

Acknowledgments. The authors thank the study participants and Dzimauli community leaders for their important contributions.

Financial support. The Etiology, Risk Factors and Interactions of Enteric Infections and Malnutrition and the Consequences for Child Health and Development Project (MAL-ED) is carried out as a collaborative project supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation; the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health; and the Fogarty International Center, National Institutes of Health.

Supplement sponsorship. This article appeared as part of the supplement “The Malnutrition and Enteric Disease Study (MAL-ED): Understanding the Consequences for Child Health and Development,” which is sponsored by the National Institutes of Health and the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

Comments