-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Michael Howlett, Ishani Mukherjee, Joop Koppenjan, Policy learning and policy networks in theory and practice: the role of policy brokers in the Indonesian biodiesel policy network, Policy and Society, Volume 36, Issue 2, June 2017, Pages 233–250, https://doi.org/10.1080/14494035.2017.1321230

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

This paper examines how learning has been treated, generally, in policy network theories and what questions have been posed, and answered, about this phenomenon to date. We examine to what extent network characteristics and especially the presence of various types of brokers impede or facilitate policy learning. Next, a case study of the policy network surrounding the sustainability of palm oil biodiesel in Indonesia over the past two decades is presented using social network analysis. This case study focuses on sustainability-oriented policy learning in the Indonesian biodiesel governance network and illustrates how network features and especially forms of brokerage influence learning.

Introduction: policy network theory and policy brokers – linking policy learning and change

The policy universe or system can be thought of as an all-encompassing aggregation of all possible state, private and social actors at various levels (local, regional, national, international) working within the institutions that directly or indirectly affect a specific policy area. The actors active in each sector or issue area can be thought of as a subset of that universe, or a policy subsystem (Cater, 1964; Freeman, 1955; Freeman & Stevens, 1987; McCool, 1998). Such subsystems are forms of social networks which encompass the interrelationships existing between elements of the policy universe active in specific knowledge and political spaces so we can find, for example, a ‘health policy network’ or subsystem, an ‘energy policy subsystem’ and so on.

During the course of their interactions with other actors, subsystem actors engage in a variety of activities from bargaining with each other over policy aims and measures, to developing and contesting policy ideas and concepts about their sector as well as the larger social and political world in which these exist. These interactions may be strategic or technical and often involve actors learning from experiences (Bennett & Howlett, 1992). They occur in the context of the institutional or collective arrangements in which policy processes unfold, which affect how the actors pursue their interests and ideas and, often, condition the extent of any learning which might occur and their success in attaining their goals and implementing their preferences (Knoke, 1996; Laumann & Knoke, 1989; Sabatier & Jenkins-Smith, 1993).

Identifying key actors in policy subsystems or networks, what brings them together, how they interact, and what effect their interaction has on a policy, are questions which have attracted the attention of many students of public policy-making and form the core of policy network theory (Keast, Mandell, & Agranoff, 2014; Kickert, Klijn, & Koppenjan, 1997; Laumann & Knoke, 1989; Rhodes, 1990, 1997; Scharpf, 1978, 1997; Sørensen & Torfing, 2007; Timmermans & Bleiklie, 1999). This theory has been used to examine the workings of many empirical subsystems and has been adapted and adopted in the study of networks at the local, sub-national, national and international levels of government. Within networks, some actors, for example, are members of knowledge- or idea-based discourse or ‘epistemic’ communities (Fischer, 1993; Hajer, 1993), while others are engaged in the active and ongoing formulation and consideration of policy options and alternatives and serve as members of political coalitions (Sabatier, 1988) or instrument constituencies (Voß & Simons, 2014). Some actors, such as ‘policy brokers’ may belong to multiple such groupings and be in positions to forge and also exert control over connections in the subsystem that would otherwise not exist, potentially playing a key role in any lesson-drawing activity and influencing the kinds of interactions undertaken by different sets of subsystem actors.1

Policy network theory has tended to concentrate on elucidating relationships of influence and the direction of interactions which occur in policy-making processes and has not made learning a key or central pillar of analysis and conceptualization (some exemptions are Klijn & Koppenjan, 2016; Knoepfel & Kissling-Näf, 1998; Koppenjan & Klijn, 2004; Lieberman, 2000; Pemberton, 2000). This literature traditionally has focused mainly on examining network structures, the effectiveness of various kinds of networks and especially upon disentangling the impact of network characteristics and network processes on policy-making.

Following Knaggård (2015) and Ingold and Varone (2011), in this contribution we discuss the relationship between policy networks and policy learning and in so doing, focus on the role played by policy brokers in this process. In particular, we explore the importance of policy network brokers and their impact on the type of learning that can prevail in a subsystem as well as, whether or not that learning results in (conditions for) policy change. We do this on the one hand by building on the concepts and frameworks of policy learning and change, inspired by amongst others Argyris and Cohen (1976), Argyris and Schon (1978), Sabatier (1988) and Hall (1993), examining their relevance for and applicability to network contexts. We then look at to what extent network characteristics contribute to the occurrence of policy learning, drawing on a social network analysis (SNA) of palm oil biodiesel policy in Indonesia over the past two decades in order to illustrate these concepts.

Types of policy learning and the role of brokers: the existing literature

Over the years scholars have developed a variety of models to help address the impact of networks on policy-making. Most studies (Cater, 1964; deHaven-Smith & Horn, 1984; Hamm, 1983; Hayes, 1978; Heclo, 1978; Rhodes, 1988; Ripley & Franklin, 1984) all developed the idea of an undifferentiated subsystem. The insight that a policy subsystem might consist of a number of sub-components was only first developed at length in the 1980s and 1990s in the works of Paul Sabatier and his colleagues (Sabatier & Jenkins-Smith, 1993). However, it is the key facet of a subsystem linking network thinking to policy learning.

The ‘advocacy coalition framework’ (ACF) Sabatier developed was one of the most sophisticated subsystem or network approaches to policy-making and was notable not only for distinguishing different types of collective actors within a subsystem but also because it specifically addressed the role of learning in network behaviour. The ACF combined the roles of knowledge and interests in the policy process, as policy actors were seen to come together for reasons of common beliefs, often based on their shared knowledge of a public problem and their common interest in pursuing certain solutions to it (Weible & Nohrstedt, 2012). The core of a coalition’s belief system, consisting of views on the nature of humankind and the ultimate desired state of affairs, was argued to be quite stable and served to hold a coalition together. This did not mean they never changed, rather that change tended to occur through several distinct processes, one being endogenous ‘learning’ or the adaptation of current beliefs and practices to changing circumstances and knowledge.

Three types of learning are generally of concern here: cognitive/technical, social/political and institutional (Hall, 1993; Koppenjan & Klijn, 2004). Cognitive or technical learning is instrumental learning about the nature of the problem, the assumptions on the causal relationships involved and the pros and cons of measures aimed to address the problem. Social or political learning implies that actors within the network learn about how to operate within a network setting and apply strategies aimed at collaboration and negotiation (Keast et al., 2014; Knoepfel & Kissling-Näf, 1998; Rhodes, 1996). Finally, institutional learning is about the development of shared and lasting arrangements, procedures, rules, norms, values and trust that reduces the risks and costs of interactions and support negotiations and collaboration (Goodin, 1996; March & Olsen, 1983; Ostrom, 1990; Williamson, 1996).

In general, which type of learning occurs in policy-making depends on the behaviour of actors within policy networks. These types often, but not necessarily coincide with how learning takes place (formal vs. informal), the level of learning (individual, coalitions, subsytems) and the extent of learning (instrumental vs. deep core) (Bennett & Howlett, 1992; Hall, 1993; Sabatier & Jenkins-Smith, 1993).

Most influential, from a network perspective, are those individuals who serve as instrumental links, or function as brokers between diverse groups or coalitions. That is, as Sabatier and his colleagues realized there was a need to account for cross-coalition and coalition-environment interactions which could lead to learning and their suggestion that policy brokers are key players in these processes and linkages is congruent with network thinking about actor inter-relationships. As Heclo (1978), propounding on the role of political brokers and societal learning, argued, brokers are ‘middlemen at the interfaces of various groups [with] access to information, ideas, and positions’ (p. 308). Exactly who these brokers are and how they promote learning, however, remains understudied almost 30 years after the first elaborations of the ACF framework (Ingold, 2011; Weible, Sabatier, & McQueen, 2009; Mintrom & Vergari, 1996).

Operationalizing and testing for the presence of the above discussed kinds of learning is beyond the scope of the research presented in this contribution. In this study we applied techniques from SNA, however, to map formal knowledge-sharing relationships and tease out brokerage linkages in a policy network that are conditional for technical or instrumental level learning.

Analysing policy brokerage through SNA

While policy brokers have been identified as key in policy learning theories, their interactions vis-à-vis the various members of a policy network and the particular positions of influence they occupy in the structure of the network itself has seldom been examined (Bennett & Howlett, 1992; Burt, 2005). Sabatier (1988) attributes a distinct conflict resolution or mediatory role on the part of policy brokers whose ‘dominant concern is with keeping the level of political conflict within acceptable limits’ (p. 141), Hall (1993) contends that the main agents of learning within a policy network, who structure the flow of information are those who ‘work for the state itself or advise it from privileged positions at the interface between bureaucracy and the intellectual enclaves of society’ (p. 281).

Methods such as SNA which explicitly espouse an agent-centric view of a policy area, may be able to reveal specific positions of information brokerage that actors of a network occupy allowing them to be in locations that facilitate the creation of various types of learning relationships and indicating conditions conducive to policy change within the network. That is, within any network a number of coalitions can emerge surrounding common beliefs with characteristic modes of knowledge transfer. A network study of policy actors in a specific sector undergoing modest change, therefore, should highlight these actors (Giest & Howlett, 2013).

SNA allows for the examination and measurement of several different types of brokers (de Nooy, Mrvar, & Batagelj, 2011; Smith, 2000; Varone, Ingold, & Jourdain, 2016). Two network concepts emerge as being important here: centrality and brokerage, both indicating the relative greater influence of some actors over others in shaping ties within the network. Centrality in a network simply indicates the central positions of those actors who have a high number of connections with other actors in the network (Freeman, 1979; Prell, 2012; Rhodes, 1981). It follows that the sub-group which contains the most number of central actors, would have the connections and resources to become a powerful or ‘dominant’ coalition within the network and, as explored in the case study below, thus have an impact on the overall interconnectedness of the subsystem.

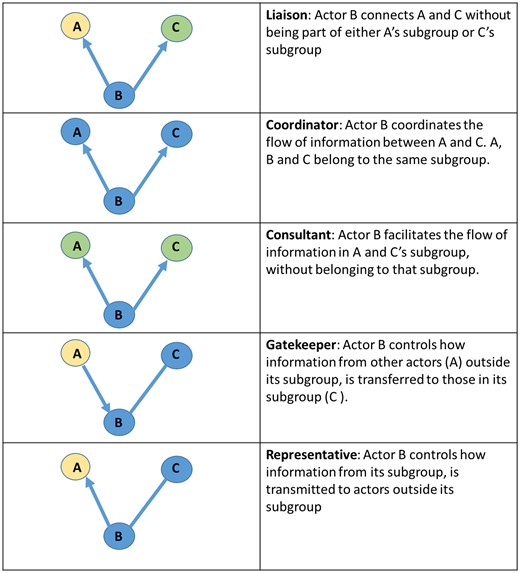

Brokers, in this context, exhibit a specific type of centrality that positions them as crucial links between otherwise disjointed sub-groups within the subsystem. Actors emerge as brokers due to their connections to many members of the network and also by exhibiting high ‘betweenness’ centrality, that is, they can form links to areas or other groups of the network that would be otherwise disconnected (Figure 1). These measurements pertain to positions that network actors can inhabit as intermediaries between different parts of the policy network position. Betweenness centrality assumes an actor to be in a powerful position in the network if this actor falls between the shortest paths connecting other actors (Prell, 2012).

Several distinct types of brokerage are possible and discernable using measures of betweenness in SNA. Brokers can act as consultants, or knowledge entrepreneurs, brokering knowledge ties among diverse groups within a policy network which would otherwise be limitedly connected (Prell, 2012). Liaison and gatekeeping activities of brokers become important conduits of these types of learning within the network by linking different sections and enhancing the interconnectedness of the entire network.

We thus can expect to find five basic types of brokers active in subsystem-based learning activities (Figure 1). Coordinators are those who bridge connections within their own group. Consultants control the flow of information between members of a group without being members themselves. A gatekeeper is a member of a group at the group’s boundary, controlling how outsiders link to the group. A representative is the member of one group that forges ties to others on behalf of that group. And lastly, a liaison brokers ties between two groups without being a part of either (see Figure 1). The presence of these different brokerage roles can be important in creating enabling conditions for policy learning in the network.

The case study set out below identifies the roles of these various kinds of brokers. By examining policy actor interactions in Indonesia around the biofuel sector, the case study established the extent to which the positions of government actors in this network were central, a position known to be conditional for affecting policy learning (Emerson, Nabatchi, & Balogh, 2012; Resh, Siddiki, & McConnell, 2014).

SNA analysis of policy brokerage in the Indonesia biofuels case

The development of biofuels has been a policy response to the energy and climate change concerns that have occupied the attention of national and international policy-makers worldwide. Volatile prices for traditional fuels such as oil, coal and natural gas have augmented national concerns about energy security and eroding balances of payment by escalating the cost of energy imports and have led to efforts to develop this sector (Koizumi & Ohga, 2007; Sorda, Banse, & Kemfert, 2010; Zhang, 2008; Zhou & Thomson, 2009). Energy networks have engaged in both small, medium and large-scale learning efforts in attempting to adapt or respond to these concerns. One concrete result of such activity has been a large increase in global production of alternate fuels – particularly those derived from plant sugars and oil crops. These efforts have flourished over the last decade with the help of government investment, national mandates and lucrative global trading opportunities. In 2012, a total of 105.6 billion litres of fuel from biomass was produced globally (REN21, 2013).

With a distinct comparative advantage in producing certain biofuel feedstock, Asian producers are poised to carve a substantial niche in the world biofuel market. However, biofuel development in the region is also shown to have had detrimental effects on environmental sustainability due the land-clearing and monoculture cultivation that have had led to issues such as loss of biodiversity, air pollution and wildlife habitat loss, among others (Koh & Wilcove, 2008; Obidzinski, Andriani, Komarudin, & Andrianto, 2012; Tan, Lee, Mohamed, & Bhatia, 2009). The policy debate about biofuels has affected policy networks in the region has thus concerned with balancing energy and environmental considerations. This is especially true in the case of Indonesia, the leading producer of regional biofuels based on oil-palm as a feedstock. As a case study, this presents a unique opportunity to examine the learning relationships of policy brokers, in that it involves relatively few actors whose linkages and behaviour can be relatively easily discerned and analysed.

The analysis proceeds by first identifying all the actors in the policy subsystem under examination and five different relationships that connect them (Table 2). After collating this list of network actors and their relationships, SNA is used to reveal prominent, dominant actors based on their ‘degree centrality’ or the number of direct connections that each has in the policy network. The dominant coalition is further specified, by looking at how many of the central actors form a cohesive clique based on a mutual agreement of policy beliefs. Next, knowledge sharing relationships are examined within the network to reveal brokers, or those actors who exhibit high ‘betweenness centrality’: the position they occupy between other pairs of actors in the network. Lastly, the brokerage positions – as either coordinators, consultants, gatekeepers, representatives or liaisons – of the most central actors are revealed.

Methods

This particular subsystem concerns a range of actors from producers of agricultural raw materials to those influencing the use of biofuel as an energy end product. The involvement of the Indonesian government with biofuels began in 2006 with Presidential Regulation No. 5 outlining the national interest in biodiesel development as part of the new national energy policy. Since then, numerous roundtable discussions, conferences, forums and ad hoc commissions have occurred concerning biodiesel development including environmental sustainability repercussions of intensive oil-palm cultivation.

These meetings represent important venues where multiple policy actors have been able to assemble and present their perspectives, and following the methods used by Howlett and Maragna (2006) records and meeting minutes were analysed in order to compile a list of organizations and individuals who participated. Biodiesel policy experts were identified as key informants through purposive sampling and snowball sampling proceeded with these key informants who were asked to name those organizations with which they thought they were most actively involved.

In order to reach actors of the entire policy network, the responses of the key informants were verified against the subsystem database to distinguish those actors who have been present for multiple meetings over the course of the last six years. Through this exercise, an initial roster of network actors was created and used to administer a network survey (Table 1).

Actors in Indonesian biodiesel policy network (2006–2012).

| Organization name | Abbreviation | Organization type |

| Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources | ESDM | Government |

| State Ministry of Research and Technology | RISTEK | Government |

| Ministry of Forestry (DEPHUT) | DEPHUT | Government |

| Ministry of Agriculture (DEPTAN) | DEPTAN | Government |

| Ministry of Trade (DEPDAG) | DEPDAG | Government |

| State Ministry of Environment (MENLH) | MENLH | Government |

| National Biofuel Development Team (TimnasBBN) | TimnasBBN | Government |

| Indonesian Palm Oil Commission (IPOC) | IPOC | Government |

| World Bank Group(IBRD-IDA, IFC, MIGA) | WBG | International |

| Asian Development Bank (ADB) | ADB | International |

| Ford Foundation | FF | International |

| Indonesian Palm Oil Producers Association (GAPKI) | GAPKI | Producer/Private |

| Association of Indonesian Biofuel Producers (APROBI) | APROBI | Producer/Private |

| Roundtable for Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) | RSPO | Producer/Private |

| PT Eterindo group | – | Producer/Private |

| PT Indo Biofuels Energy | – | Producer/Private |

| PT Wilmar | – | Producer/Private |

| PT Sumi Asih | – | Producer/Private |

| PT Musim Mas | – | Producer/Private |

| Sinar Mas | – | Producer/Private |

| Salim/Indofood | – | Producer/Private |

| Indonesian Institute of Sciences (LIPI) | LIPI | Academic |

| Bogor Agricultural University (IPB) | IPB | Academic |

| CGIAR (Including CIFOR and ICRAF) | CGIAR | Academic |

| Indonesian Bioenergy Experts Partnership | IKABI | Academic |

| Renewable Energy Forum of Indonesia | METI | Academic |

| Wahana Lingkungan Hidup Indonesia | WALHI | NGO |

| Sawitwatch | – | NGO |

| World Wildlife Fund (WWF) | WWF | NGO |

| Conservation International (CI) | CI | NGO |

| Non-Timber Forest Products/SETARA | NTFP | NGO |

| University of Papua – Tanjung Pura | – | Academic |

| Indonesian Palm Oil Research Institute (PPKS/IOPRI) | IOPRI | Academic |

| Institute of Technology Bandung (ITB) | ITB | Academic |

| Gaikindo (automobile association) | – | Producer/Private |

| PT Mutuagung Lestari (certification) | – | Certification Agency |

| Pertamina (Persero) | – | State Owned Entrp. |

| PT Bayer | – | Producer/Private |

| LINKS | LINKS | NGO |

| PT Sai Global | – | Certification Agency |

| PT TUV Nord | – | Certification Agency |

| PT Sucofindo | – | Certification Agency |

| APKASINDO (Palm Oil Smallholder Association) | APKASINDO | Producer/Private |

| GPPI (association of plantations) | GPPI | Producer/Private |

| Indonesian Palm Oil Society | MAKSI | Academic |

| Ministry of Transport | MENTRAN | Government |

| National Development Planning Agency | Bappenas | Government |

| Organization name | Abbreviation | Organization type |

| Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources | ESDM | Government |

| State Ministry of Research and Technology | RISTEK | Government |

| Ministry of Forestry (DEPHUT) | DEPHUT | Government |

| Ministry of Agriculture (DEPTAN) | DEPTAN | Government |

| Ministry of Trade (DEPDAG) | DEPDAG | Government |

| State Ministry of Environment (MENLH) | MENLH | Government |

| National Biofuel Development Team (TimnasBBN) | TimnasBBN | Government |

| Indonesian Palm Oil Commission (IPOC) | IPOC | Government |

| World Bank Group(IBRD-IDA, IFC, MIGA) | WBG | International |

| Asian Development Bank (ADB) | ADB | International |

| Ford Foundation | FF | International |

| Indonesian Palm Oil Producers Association (GAPKI) | GAPKI | Producer/Private |

| Association of Indonesian Biofuel Producers (APROBI) | APROBI | Producer/Private |

| Roundtable for Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) | RSPO | Producer/Private |

| PT Eterindo group | – | Producer/Private |

| PT Indo Biofuels Energy | – | Producer/Private |

| PT Wilmar | – | Producer/Private |

| PT Sumi Asih | – | Producer/Private |

| PT Musim Mas | – | Producer/Private |

| Sinar Mas | – | Producer/Private |

| Salim/Indofood | – | Producer/Private |

| Indonesian Institute of Sciences (LIPI) | LIPI | Academic |

| Bogor Agricultural University (IPB) | IPB | Academic |

| CGIAR (Including CIFOR and ICRAF) | CGIAR | Academic |

| Indonesian Bioenergy Experts Partnership | IKABI | Academic |

| Renewable Energy Forum of Indonesia | METI | Academic |

| Wahana Lingkungan Hidup Indonesia | WALHI | NGO |

| Sawitwatch | – | NGO |

| World Wildlife Fund (WWF) | WWF | NGO |

| Conservation International (CI) | CI | NGO |

| Non-Timber Forest Products/SETARA | NTFP | NGO |

| University of Papua – Tanjung Pura | – | Academic |

| Indonesian Palm Oil Research Institute (PPKS/IOPRI) | IOPRI | Academic |

| Institute of Technology Bandung (ITB) | ITB | Academic |

| Gaikindo (automobile association) | – | Producer/Private |

| PT Mutuagung Lestari (certification) | – | Certification Agency |

| Pertamina (Persero) | – | State Owned Entrp. |

| PT Bayer | – | Producer/Private |

| LINKS | LINKS | NGO |

| PT Sai Global | – | Certification Agency |

| PT TUV Nord | – | Certification Agency |

| PT Sucofindo | – | Certification Agency |

| APKASINDO (Palm Oil Smallholder Association) | APKASINDO | Producer/Private |

| GPPI (association of plantations) | GPPI | Producer/Private |

| Indonesian Palm Oil Society | MAKSI | Academic |

| Ministry of Transport | MENTRAN | Government |

| National Development Planning Agency | Bappenas | Government |

| Organization name | Abbreviation | Organization type |

| Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources | ESDM | Government |

| State Ministry of Research and Technology | RISTEK | Government |

| Ministry of Forestry (DEPHUT) | DEPHUT | Government |

| Ministry of Agriculture (DEPTAN) | DEPTAN | Government |

| Ministry of Trade (DEPDAG) | DEPDAG | Government |

| State Ministry of Environment (MENLH) | MENLH | Government |

| National Biofuel Development Team (TimnasBBN) | TimnasBBN | Government |

| Indonesian Palm Oil Commission (IPOC) | IPOC | Government |

| World Bank Group(IBRD-IDA, IFC, MIGA) | WBG | International |

| Asian Development Bank (ADB) | ADB | International |

| Ford Foundation | FF | International |

| Indonesian Palm Oil Producers Association (GAPKI) | GAPKI | Producer/Private |

| Association of Indonesian Biofuel Producers (APROBI) | APROBI | Producer/Private |

| Roundtable for Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) | RSPO | Producer/Private |

| PT Eterindo group | – | Producer/Private |

| PT Indo Biofuels Energy | – | Producer/Private |

| PT Wilmar | – | Producer/Private |

| PT Sumi Asih | – | Producer/Private |

| PT Musim Mas | – | Producer/Private |

| Sinar Mas | – | Producer/Private |

| Salim/Indofood | – | Producer/Private |

| Indonesian Institute of Sciences (LIPI) | LIPI | Academic |

| Bogor Agricultural University (IPB) | IPB | Academic |

| CGIAR (Including CIFOR and ICRAF) | CGIAR | Academic |

| Indonesian Bioenergy Experts Partnership | IKABI | Academic |

| Renewable Energy Forum of Indonesia | METI | Academic |

| Wahana Lingkungan Hidup Indonesia | WALHI | NGO |

| Sawitwatch | – | NGO |

| World Wildlife Fund (WWF) | WWF | NGO |

| Conservation International (CI) | CI | NGO |

| Non-Timber Forest Products/SETARA | NTFP | NGO |

| University of Papua – Tanjung Pura | – | Academic |

| Indonesian Palm Oil Research Institute (PPKS/IOPRI) | IOPRI | Academic |

| Institute of Technology Bandung (ITB) | ITB | Academic |

| Gaikindo (automobile association) | – | Producer/Private |

| PT Mutuagung Lestari (certification) | – | Certification Agency |

| Pertamina (Persero) | – | State Owned Entrp. |

| PT Bayer | – | Producer/Private |

| LINKS | LINKS | NGO |

| PT Sai Global | – | Certification Agency |

| PT TUV Nord | – | Certification Agency |

| PT Sucofindo | – | Certification Agency |

| APKASINDO (Palm Oil Smallholder Association) | APKASINDO | Producer/Private |

| GPPI (association of plantations) | GPPI | Producer/Private |

| Indonesian Palm Oil Society | MAKSI | Academic |

| Ministry of Transport | MENTRAN | Government |

| National Development Planning Agency | Bappenas | Government |

| Organization name | Abbreviation | Organization type |

| Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources | ESDM | Government |

| State Ministry of Research and Technology | RISTEK | Government |

| Ministry of Forestry (DEPHUT) | DEPHUT | Government |

| Ministry of Agriculture (DEPTAN) | DEPTAN | Government |

| Ministry of Trade (DEPDAG) | DEPDAG | Government |

| State Ministry of Environment (MENLH) | MENLH | Government |

| National Biofuel Development Team (TimnasBBN) | TimnasBBN | Government |

| Indonesian Palm Oil Commission (IPOC) | IPOC | Government |

| World Bank Group(IBRD-IDA, IFC, MIGA) | WBG | International |

| Asian Development Bank (ADB) | ADB | International |

| Ford Foundation | FF | International |

| Indonesian Palm Oil Producers Association (GAPKI) | GAPKI | Producer/Private |

| Association of Indonesian Biofuel Producers (APROBI) | APROBI | Producer/Private |

| Roundtable for Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) | RSPO | Producer/Private |

| PT Eterindo group | – | Producer/Private |

| PT Indo Biofuels Energy | – | Producer/Private |

| PT Wilmar | – | Producer/Private |

| PT Sumi Asih | – | Producer/Private |

| PT Musim Mas | – | Producer/Private |

| Sinar Mas | – | Producer/Private |

| Salim/Indofood | – | Producer/Private |

| Indonesian Institute of Sciences (LIPI) | LIPI | Academic |

| Bogor Agricultural University (IPB) | IPB | Academic |

| CGIAR (Including CIFOR and ICRAF) | CGIAR | Academic |

| Indonesian Bioenergy Experts Partnership | IKABI | Academic |

| Renewable Energy Forum of Indonesia | METI | Academic |

| Wahana Lingkungan Hidup Indonesia | WALHI | NGO |

| Sawitwatch | – | NGO |

| World Wildlife Fund (WWF) | WWF | NGO |

| Conservation International (CI) | CI | NGO |

| Non-Timber Forest Products/SETARA | NTFP | NGO |

| University of Papua – Tanjung Pura | – | Academic |

| Indonesian Palm Oil Research Institute (PPKS/IOPRI) | IOPRI | Academic |

| Institute of Technology Bandung (ITB) | ITB | Academic |

| Gaikindo (automobile association) | – | Producer/Private |

| PT Mutuagung Lestari (certification) | – | Certification Agency |

| Pertamina (Persero) | – | State Owned Entrp. |

| PT Bayer | – | Producer/Private |

| LINKS | LINKS | NGO |

| PT Sai Global | – | Certification Agency |

| PT TUV Nord | – | Certification Agency |

| PT Sucofindo | – | Certification Agency |

| APKASINDO (Palm Oil Smallholder Association) | APKASINDO | Producer/Private |

| GPPI (association of plantations) | GPPI | Producer/Private |

| Indonesian Palm Oil Society | MAKSI | Academic |

| Ministry of Transport | MENTRAN | Government |

| National Development Planning Agency | Bappenas | Government |

Data collection proceeded by presenting the roster to every actor in the network and asking them to identify those organizations on the list (or any other) with which they shared a relationship. Keeping pace with the most contemporary studies that focus on determining coalition structure (Henry, 2011; Ingold, 2011) based on SNA, the identification of the dominant coalition was subject to three network assumptions. (Ingold, 2011; Wasserman & Faust, 1994):

- (1)

Members of a coalition have positive density: collaborative relations should link actors from the same coalition.

- (2)

Conflictive relations define relations between members of opposing coalitions.

- (3)

Members of the same coalition are structurally equivalent. ‘They should share the same cooperation and conflict profile with other actors in the same coalition’ (Ingold, 2011, 441).

Following Ingold (2011) and others (see Table 2), six network relationships or variables pertinent to the sustainability of biofuels were specified: collaboration, conflict, knowledge sharing, perceived influence, perceived agreement and perceived disagreement, as well as a variable for shared membership in multi-stakeholder associations (affiliations) (Henry, 2011; Ingold, 2011; Weible & Nohrstedt, 2012).

Network variables and definitions.

| Network variable | Definition |

| Collaboration | Formal and/or informal professional collaboration and sharing of information during biodiesel policy development |

| Conflict | Conflictive relations during biodiesel policy development |

| Knowledge | Exchange of scientific knowledge and findings concerning biodiesel policy sustainability |

| Perceived Agreement | Having the same opinion regarding prioritizing sustainability in biodiesel policy |

| Perceived Disagreement | Having a different opinion regarding prioritizing sustainability in biodiesel policy |

| Perceived Influence | Believed to be influential in biodiesel policy development. |

| Affiliation | Being members of the same Multi-stakeholder associations |

| Network variable | Definition |

| Collaboration | Formal and/or informal professional collaboration and sharing of information during biodiesel policy development |

| Conflict | Conflictive relations during biodiesel policy development |

| Knowledge | Exchange of scientific knowledge and findings concerning biodiesel policy sustainability |

| Perceived Agreement | Having the same opinion regarding prioritizing sustainability in biodiesel policy |

| Perceived Disagreement | Having a different opinion regarding prioritizing sustainability in biodiesel policy |

| Perceived Influence | Believed to be influential in biodiesel policy development. |

| Affiliation | Being members of the same Multi-stakeholder associations |

| Network variable | Definition |

| Collaboration | Formal and/or informal professional collaboration and sharing of information during biodiesel policy development |

| Conflict | Conflictive relations during biodiesel policy development |

| Knowledge | Exchange of scientific knowledge and findings concerning biodiesel policy sustainability |

| Perceived Agreement | Having the same opinion regarding prioritizing sustainability in biodiesel policy |

| Perceived Disagreement | Having a different opinion regarding prioritizing sustainability in biodiesel policy |

| Perceived Influence | Believed to be influential in biodiesel policy development. |

| Affiliation | Being members of the same Multi-stakeholder associations |

| Network variable | Definition |

| Collaboration | Formal and/or informal professional collaboration and sharing of information during biodiesel policy development |

| Conflict | Conflictive relations during biodiesel policy development |

| Knowledge | Exchange of scientific knowledge and findings concerning biodiesel policy sustainability |

| Perceived Agreement | Having the same opinion regarding prioritizing sustainability in biodiesel policy |

| Perceived Disagreement | Having a different opinion regarding prioritizing sustainability in biodiesel policy |

| Perceived Influence | Believed to be influential in biodiesel policy development. |

| Affiliation | Being members of the same Multi-stakeholder associations |

The dominant coalition was identified by highlighting actors with high centrality in the collaboration network – based on formal working relationships during biodiesel policy development – and then testing which of these actors also formed a cohesive sub-group (or ‘clique’) in the matrix defined by relationships of agreement regarding the prioritizing of sustainability in biodiesel policy formulation. This revealed six organizations making up the dominant coalition in the biodiesel policy subsystem (Table 3).

Members of dominant coalition within the biodiesel policy network.

| Organization name | Type | Centrality | |

| InDegreea | Outdegreeb | ||

| Ministry of Energy (ESDM) | Government | 17 (36.17%) | 12 (25.53%) |

| State Ministry of Research and Technology (RISTEK) | Government | 30 (63.83%) | 33 (70.21%) |

| Ministry of Agriculture (DEPTAN) | Government | 15 (31.92%) | 10 (21.28%) |

| National Biofuels Team (Timnas BBN) | Government | 10 (21.28%) | 13 (27.66%) |

| APROBI | Producer/Pvt | 17 (36.17%) | 19 (40.43%) |

| PT Musim Mas | Producer/Pvt | 15 (31.92%) | 20 (42.55%) |

| Organization name | Type | Centrality | |

| InDegreea | Outdegreeb | ||

| Ministry of Energy (ESDM) | Government | 17 (36.17%) | 12 (25.53%) |

| State Ministry of Research and Technology (RISTEK) | Government | 30 (63.83%) | 33 (70.21%) |

| Ministry of Agriculture (DEPTAN) | Government | 15 (31.92%) | 10 (21.28%) |

| National Biofuels Team (Timnas BBN) | Government | 10 (21.28%) | 13 (27.66%) |

| APROBI | Producer/Pvt | 17 (36.17%) | 19 (40.43%) |

| PT Musim Mas | Producer/Pvt | 15 (31.92%) | 20 (42.55%) |

aInDegree indicates the number of ties directed at the organization.

bOutDegree indicates the number of ties originating out of the organization.

| Organization name | Type | Centrality | |

| InDegreea | Outdegreeb | ||

| Ministry of Energy (ESDM) | Government | 17 (36.17%) | 12 (25.53%) |

| State Ministry of Research and Technology (RISTEK) | Government | 30 (63.83%) | 33 (70.21%) |

| Ministry of Agriculture (DEPTAN) | Government | 15 (31.92%) | 10 (21.28%) |

| National Biofuels Team (Timnas BBN) | Government | 10 (21.28%) | 13 (27.66%) |

| APROBI | Producer/Pvt | 17 (36.17%) | 19 (40.43%) |

| PT Musim Mas | Producer/Pvt | 15 (31.92%) | 20 (42.55%) |

| Organization name | Type | Centrality | |

| InDegreea | Outdegreeb | ||

| Ministry of Energy (ESDM) | Government | 17 (36.17%) | 12 (25.53%) |

| State Ministry of Research and Technology (RISTEK) | Government | 30 (63.83%) | 33 (70.21%) |

| Ministry of Agriculture (DEPTAN) | Government | 15 (31.92%) | 10 (21.28%) |

| National Biofuels Team (Timnas BBN) | Government | 10 (21.28%) | 13 (27.66%) |

| APROBI | Producer/Pvt | 17 (36.17%) | 19 (40.43%) |

| PT Musim Mas | Producer/Pvt | 15 (31.92%) | 20 (42.55%) |

aInDegree indicates the number of ties directed at the organization.

bOutDegree indicates the number of ties originating out of the organization.

Dominant policy actors, brokers and learning in the Indonesian biodiesel governance network

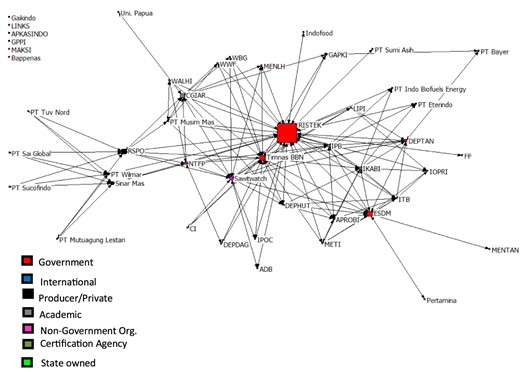

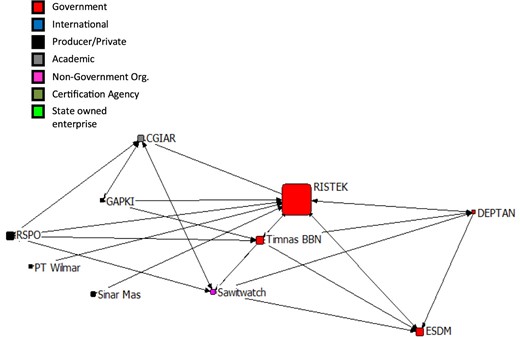

To explore the relationships based on knowledge sharing within the network, and the incidence of brokers of learning ties, the ‘knowledge’ network was then explored analysing ties in the network based on the exchange of scientific knowledge findings concerning biodiesel policy sustainability. Figure 2 displays the full knowledge matrix and Figure 3 summarizes the measures of those actors who exhibit above average betweenness centralities therein.

Structure of knowledge network (node size corresponding to relative betweenness centrality).

Central actors in knowledge network (between centrality > 40.362).

The actors displaying above average betweenness centrality measures are tabulated in Table 4 alongside those who showed high degree centrality in the collaboration matrix. The common organizations of the dominant coalition, are shaded. This exercise indicated that four government organizations from the dominant coalition – the GOI Ministry of Energy (ESDM), the GOI State Ministry of Research and Technology (RISTEK), GOI Ministry of Agriculture (DEPTAN) and the national biofuels taskforce (Timnas BBN) – have all been in central brokerage positions, and are influential in the exchange of scientific information in the biodiesel policy network.

Knowledge brokers in the biodiesel policy network (shaded).

| Matrix: knowledge | Matrix: collaboration | ||

| Organization | Betweenness | Organization | Degree |

| RISTEK | 892.2297363 (43.10%) | ESDM | 17 (36.17%) |

| RSPO | 171.0459747 (8.26%) | RISTEK | 30 (63.83%) |

| ESDM | 164.8691711 (7.96%) | DEPTAN | 15 (31.92%) |

| Timnas BBN | 128.5689087 (6.21%) | Ministry of Trade | 9 (19.15%) |

| CGIAR | 104.8019257 (5%) | Timnas BBN | 10 (21.28%) |

| Matrix: knowledge | Matrix: collaboration | ||

| Organization | Betweenness | Organization | Degree |

| RISTEK | 892.2297363 (43.10%) | ESDM | 17 (36.17%) |

| RSPO | 171.0459747 (8.26%) | RISTEK | 30 (63.83%) |

| ESDM | 164.8691711 (7.96%) | DEPTAN | 15 (31.92%) |

| Timnas BBN | 128.5689087 (6.21%) | Ministry of Trade | 9 (19.15%) |

| CGIAR | 104.8019257 (5%) | Timnas BBN | 10 (21.28%) |

| Matrix: knowledge | Matrix: collaboration | ||

| Organization | Betweenness | Organization | Degree |

| RISTEK | 892.2297363 (43.10%) | ESDM | 17 (36.17%) |

| RSPO | 171.0459747 (8.26%) | RISTEK | 30 (63.83%) |

| ESDM | 164.8691711 (7.96%) | DEPTAN | 15 (31.92%) |

| Timnas BBN | 128.5689087 (6.21%) | Ministry of Trade | 9 (19.15%) |

| CGIAR | 104.8019257 (5%) | Timnas BBN | 10 (21.28%) |

| Matrix: knowledge | Matrix: collaboration | ||

| Organization | Betweenness | Organization | Degree |

| RISTEK | 892.2297363 (43.10%) | ESDM | 17 (36.17%) |

| RSPO | 171.0459747 (8.26%) | RISTEK | 30 (63.83%) |

| ESDM | 164.8691711 (7.96%) | DEPTAN | 15 (31.92%) |

| Timnas BBN | 128.5689087 (6.21%) | Ministry of Trade | 9 (19.15%) |

| CGIAR | 104.8019257 (5%) | Timnas BBN | 10 (21.28%) |

As is apparent in Table 4, RISTEK, occupies the most prominent position in the knowledge matrix in terms of betweenness centrality. Approximately 43% of the number of all possible technical knowledge sharing paths that can go through RISTEK as a node in the network, are present and its centrality measure is roughly 5 times greater than the next largest node, which is the Roundtable for Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO). RISTEK’s is thus an organization that plays a significant information bridging or brokerage role within different groups within the network, without which these groups (who are likely to possess different sets of knowledge) may not be connected and instead contain disjointing structural ‘holes’.

An SNA analysis of this network illustrates the ability of this method to identify the key role that the dominant coalition members, and especially RISTEK, play as brokers forging learning ties within the biodiesel network. It also helps reveal what type of brokering role these organizations assume, and which other organizations (not part of the dominant coalition) also are important knowledge brokers.

This is apparent in Table 5, where the biodiesel policy network members are organized by type and number of brokerage ties is specified. RISTEK, again, has the highest amount and diversity of broker activity in the network. Most of its brokerage occurs in the role of liaison, meaning that it is one government organization that facilitates knowledge exchange between other, non-state groups. Its second highest brokering role is that of a representative that is almost singularly responsible for forging government ties of knowledge exchange with other groups.

Types of brokers in knowledge matrix.

| Organization type and name | Broker type | |||||

| Coordinator | Gatekeeper | Representative | Consultant | Liaison | Total | |

| Government | ||||||

| Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources (ESDM) | 7 | 13 | 18 | 4 | 16 | 58 |

| State Ministry of Research and Technology (RISTEK) | 29 | 133 | 147 | 120 | 359 | 788 |

| Ministry of Forestry (DEPHUT) | 1 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 7 | 21 |

| Ministry of Agriculture (DEPTAN) | 0 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 16 |

| Ministry of Trade (DEPDAG) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| State Ministry of Environment (MENLH) | 0 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| National Biofuel Development Team (TimnasBBN) | 19 | 50 | 46 | 21 | 76 | 212 |

| Indonesian Palm Oil Commission (IPOC) | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| National Development Planning Agency (BAPPENAS) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ministry of Transportation (MENTAN) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| International | ||||||

| World Bank Group(IBRD-IDA, IFC, MIGA) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 5 |

| Asian Development Bank (ADB) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Ford Foundation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Producer/Private Sector | ||||||

| Roundtable for Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) | 0 | 8 | 7 | 12 | 47 | 74 |

| PT Eterindo group | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PT. Indo Biofuels Energy | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PT Wilmar | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 8 | 20 |

| PT Sumi Asih | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PT Musim Mas | 0 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 12 |

| Sinar Mas | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 16 | 28 |

| Salim/Indofood | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Association of Plantations (GPPI) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Indonesian Palm Oil Producers Association (GAPKI) | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 9 |

| Association of Indonesian Biofuel Producers (APROBI) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 10 | 14 |

| Gaikindo (automobile association) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Palm Oil Smallholder Association (APKASINDO) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PT Bayer | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Academic | ||||||

| Renewable Energy Forum of Indonesia (METI | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| Institute of Technology Bandung (ITB) | 8 | 5 | 8 | 2 | 1 | 24 |

| Indonesian Institute of Sciences (LIPI) | 0 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 10 |

| CGIAR (Including CIFOR and ICRAF) | 0 | 10 | 7 | 8 | 35 | 60 |

| Indonesian Bioenergy Experts Partnership (IKABI) | 2 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 7 | 25 |

| University of Papua – Tanjung Pura | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Indonesian Palm Oil Research Institute (PPKS/IOPRI) | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Indonesian Palm Oil Society (MAKSI) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bogor Agricultural University (IPB) | 0 | 6 | 2 | 10 | 17 | 35 |

| Non-Government | ||||||

| World Wildlife Fund (WWF) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 7 |

| Sawitwatch | 2 | 17 | 19 | 17 | 63 | 118 |

| Non-Timber Forest Products/SETARA (NTFP) | 2 | 5 | 8 | 2 | 11 | 28 |

| Conservation International (CI) | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Wahana Lingkungan Hidup Indonesia (WALHI) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 6 |

| LINKS | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Certification Agency | ||||||

| PT Sucofindo | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 6 |

| PT Mutuagung Lestari | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 6 |

| PT Sai Global | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 6 |

| PT TUV Nord | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 6 |

| Organization type and name | Broker type | |||||

| Coordinator | Gatekeeper | Representative | Consultant | Liaison | Total | |

| Government | ||||||

| Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources (ESDM) | 7 | 13 | 18 | 4 | 16 | 58 |

| State Ministry of Research and Technology (RISTEK) | 29 | 133 | 147 | 120 | 359 | 788 |

| Ministry of Forestry (DEPHUT) | 1 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 7 | 21 |

| Ministry of Agriculture (DEPTAN) | 0 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 16 |

| Ministry of Trade (DEPDAG) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| State Ministry of Environment (MENLH) | 0 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| National Biofuel Development Team (TimnasBBN) | 19 | 50 | 46 | 21 | 76 | 212 |

| Indonesian Palm Oil Commission (IPOC) | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| National Development Planning Agency (BAPPENAS) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ministry of Transportation (MENTAN) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| International | ||||||

| World Bank Group(IBRD-IDA, IFC, MIGA) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 5 |

| Asian Development Bank (ADB) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Ford Foundation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Producer/Private Sector | ||||||

| Roundtable for Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) | 0 | 8 | 7 | 12 | 47 | 74 |

| PT Eterindo group | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PT. Indo Biofuels Energy | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PT Wilmar | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 8 | 20 |

| PT Sumi Asih | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PT Musim Mas | 0 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 12 |

| Sinar Mas | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 16 | 28 |

| Salim/Indofood | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Association of Plantations (GPPI) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Indonesian Palm Oil Producers Association (GAPKI) | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 9 |

| Association of Indonesian Biofuel Producers (APROBI) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 10 | 14 |

| Gaikindo (automobile association) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Palm Oil Smallholder Association (APKASINDO) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PT Bayer | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Academic | ||||||

| Renewable Energy Forum of Indonesia (METI | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| Institute of Technology Bandung (ITB) | 8 | 5 | 8 | 2 | 1 | 24 |

| Indonesian Institute of Sciences (LIPI) | 0 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 10 |

| CGIAR (Including CIFOR and ICRAF) | 0 | 10 | 7 | 8 | 35 | 60 |

| Indonesian Bioenergy Experts Partnership (IKABI) | 2 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 7 | 25 |

| University of Papua – Tanjung Pura | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Indonesian Palm Oil Research Institute (PPKS/IOPRI) | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Indonesian Palm Oil Society (MAKSI) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bogor Agricultural University (IPB) | 0 | 6 | 2 | 10 | 17 | 35 |

| Non-Government | ||||||

| World Wildlife Fund (WWF) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 7 |

| Sawitwatch | 2 | 17 | 19 | 17 | 63 | 118 |

| Non-Timber Forest Products/SETARA (NTFP) | 2 | 5 | 8 | 2 | 11 | 28 |

| Conservation International (CI) | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Wahana Lingkungan Hidup Indonesia (WALHI) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 6 |

| LINKS | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Certification Agency | ||||||

| PT Sucofindo | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 6 |

| PT Mutuagung Lestari | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 6 |

| PT Sai Global | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 6 |

| PT TUV Nord | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 6 |

| Organization type and name | Broker type | |||||

| Coordinator | Gatekeeper | Representative | Consultant | Liaison | Total | |

| Government | ||||||

| Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources (ESDM) | 7 | 13 | 18 | 4 | 16 | 58 |

| State Ministry of Research and Technology (RISTEK) | 29 | 133 | 147 | 120 | 359 | 788 |

| Ministry of Forestry (DEPHUT) | 1 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 7 | 21 |

| Ministry of Agriculture (DEPTAN) | 0 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 16 |

| Ministry of Trade (DEPDAG) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| State Ministry of Environment (MENLH) | 0 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| National Biofuel Development Team (TimnasBBN) | 19 | 50 | 46 | 21 | 76 | 212 |

| Indonesian Palm Oil Commission (IPOC) | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| National Development Planning Agency (BAPPENAS) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ministry of Transportation (MENTAN) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| International | ||||||

| World Bank Group(IBRD-IDA, IFC, MIGA) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 5 |

| Asian Development Bank (ADB) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Ford Foundation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Producer/Private Sector | ||||||

| Roundtable for Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) | 0 | 8 | 7 | 12 | 47 | 74 |

| PT Eterindo group | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PT. Indo Biofuels Energy | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PT Wilmar | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 8 | 20 |

| PT Sumi Asih | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PT Musim Mas | 0 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 12 |

| Sinar Mas | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 16 | 28 |

| Salim/Indofood | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Association of Plantations (GPPI) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Indonesian Palm Oil Producers Association (GAPKI) | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 9 |

| Association of Indonesian Biofuel Producers (APROBI) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 10 | 14 |

| Gaikindo (automobile association) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Palm Oil Smallholder Association (APKASINDO) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PT Bayer | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Academic | ||||||

| Renewable Energy Forum of Indonesia (METI | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| Institute of Technology Bandung (ITB) | 8 | 5 | 8 | 2 | 1 | 24 |

| Indonesian Institute of Sciences (LIPI) | 0 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 10 |

| CGIAR (Including CIFOR and ICRAF) | 0 | 10 | 7 | 8 | 35 | 60 |

| Indonesian Bioenergy Experts Partnership (IKABI) | 2 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 7 | 25 |

| University of Papua – Tanjung Pura | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Indonesian Palm Oil Research Institute (PPKS/IOPRI) | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Indonesian Palm Oil Society (MAKSI) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bogor Agricultural University (IPB) | 0 | 6 | 2 | 10 | 17 | 35 |

| Non-Government | ||||||

| World Wildlife Fund (WWF) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 7 |

| Sawitwatch | 2 | 17 | 19 | 17 | 63 | 118 |

| Non-Timber Forest Products/SETARA (NTFP) | 2 | 5 | 8 | 2 | 11 | 28 |

| Conservation International (CI) | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Wahana Lingkungan Hidup Indonesia (WALHI) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 6 |

| LINKS | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Certification Agency | ||||||

| PT Sucofindo | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 6 |

| PT Mutuagung Lestari | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 6 |

| PT Sai Global | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 6 |

| PT TUV Nord | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 6 |

| Organization type and name | Broker type | |||||

| Coordinator | Gatekeeper | Representative | Consultant | Liaison | Total | |

| Government | ||||||

| Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources (ESDM) | 7 | 13 | 18 | 4 | 16 | 58 |

| State Ministry of Research and Technology (RISTEK) | 29 | 133 | 147 | 120 | 359 | 788 |

| Ministry of Forestry (DEPHUT) | 1 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 7 | 21 |

| Ministry of Agriculture (DEPTAN) | 0 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 16 |

| Ministry of Trade (DEPDAG) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| State Ministry of Environment (MENLH) | 0 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| National Biofuel Development Team (TimnasBBN) | 19 | 50 | 46 | 21 | 76 | 212 |

| Indonesian Palm Oil Commission (IPOC) | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| National Development Planning Agency (BAPPENAS) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ministry of Transportation (MENTAN) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| International | ||||||

| World Bank Group(IBRD-IDA, IFC, MIGA) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 5 |

| Asian Development Bank (ADB) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Ford Foundation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Producer/Private Sector | ||||||

| Roundtable for Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) | 0 | 8 | 7 | 12 | 47 | 74 |

| PT Eterindo group | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PT. Indo Biofuels Energy | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PT Wilmar | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 8 | 20 |

| PT Sumi Asih | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PT Musim Mas | 0 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 12 |

| Sinar Mas | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 16 | 28 |

| Salim/Indofood | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Association of Plantations (GPPI) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Indonesian Palm Oil Producers Association (GAPKI) | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 9 |

| Association of Indonesian Biofuel Producers (APROBI) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 10 | 14 |

| Gaikindo (automobile association) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Palm Oil Smallholder Association (APKASINDO) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PT Bayer | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Academic | ||||||

| Renewable Energy Forum of Indonesia (METI | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| Institute of Technology Bandung (ITB) | 8 | 5 | 8 | 2 | 1 | 24 |

| Indonesian Institute of Sciences (LIPI) | 0 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 10 |

| CGIAR (Including CIFOR and ICRAF) | 0 | 10 | 7 | 8 | 35 | 60 |

| Indonesian Bioenergy Experts Partnership (IKABI) | 2 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 7 | 25 |

| University of Papua – Tanjung Pura | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Indonesian Palm Oil Research Institute (PPKS/IOPRI) | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Indonesian Palm Oil Society (MAKSI) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bogor Agricultural University (IPB) | 0 | 6 | 2 | 10 | 17 | 35 |

| Non-Government | ||||||

| World Wildlife Fund (WWF) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 7 |

| Sawitwatch | 2 | 17 | 19 | 17 | 63 | 118 |

| Non-Timber Forest Products/SETARA (NTFP) | 2 | 5 | 8 | 2 | 11 | 28 |

| Conservation International (CI) | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Wahana Lingkungan Hidup Indonesia (WALHI) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 6 |

| LINKS | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Certification Agency | ||||||

| PT Sucofindo | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 6 |

| PT Mutuagung Lestari | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 6 |

| PT Sai Global | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 6 |

| PT TUV Nord | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 6 |

Timnas BBN, as a group, is the second most powerful broker in the government group with its highest role as that of liaison between other groups, like RISTEK. Its second highest role is that of gatekeeper, controlling the flow of scientific and technical knowledge entering state agencies from non-state communities within the network. Together then, the results show that RISTEK and the members of Timnas BBN control much of the flow of information that goes out of and comes into the dominant coalition, and thus any learning which might occur in the process of biodiesel policy-making.

From outside the dominant coalition, the non-governmental organization Sawitwatch is also an important broker of knowledge. As an NGO significantly involved in sustainability and palm oil discussions, this organization influences the network firstly as a knowledge liaison between other groups. It also has some impact as a knowledge consultant to other groups, as a gatekeeper of knowledge entering the NGO group and as an important representative for the knowledge generated by the NGO group. Among academics, the Consultative Group of International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) and Bogor Agricultural University (IPB) are important liaisons between other groups while other academic agencies such as the Institute of Technology at Bandung (ITB) and the bioenergy experts’ association (IKABI) function as gatekeeper and coordinator roles among researchers. The international/multilateral organizations do not have a strong role in information exchange within the network. And the certification agents purely act as consultants as they carry out sustainability audits on behalf of the ISPO.

Conclusions: network structure, brokers and learning

The relationships presented in this brief case study point to several findings about the interconnectedness and knowledge sharing relationships found in subsystems and the ability of SNA to identify key policy brokers.

First, the ‘core’ of the biodiesel network consists mostly of government, some industry and few academic/research organizations. No international, multilateral or non-government organizations are found in the core, these instead make up the network ‘periphery’. The Ministry of Agriculture (DEPTAN) and RISTEK share the longest history of collaboration as co-members of almost all of the associations that are relevant to palm oil and biodiesel (1998 onwards). The Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources (ESDM) joins DEPTAN and RISTEK as a significant co-member from 2002 onwards. This corresponds to the network analysis principle that it is the overall network structure and not agency type that is most important in the analysis of learning.

Second, the dominant coalition consists of four government organizations/ministries: ESDM, RISTEK, DEPTAN and Timnas, and two industry members, APROBI and PT Musim Mas. Collaboration between these groups has a positive effect on knowledge exchange. The four government organizations of the dominant coalition have highly influential, information sharing positions in the knowledge matrix. In order of highest to lowest impact: RISTEK, Timnas BBN, ESDM and DEPTAN. The RISTEK and Timnas BBN have the most control of the knowledge and information that enters and leaves the dominant coalition and gets included during biodiesel policy-making.

This analysis results in several observations pertinent to the role of policy brokers in policy learning. The case illustrates that in governing systems such as that in Indonesia, authoritative government officials are key to technical policy learning and form the core of policy-making and knowledge transfer connections within the network. These positions of power also mean that key officials are in positions to both proliferate and inhibit learning pathways to sustainability oriented policy change in present biodiesel instruments. The positions of RISTEK and Timnas BBN as liaisons indicate their influence on how learning regarding biodiesel sustainability conceivably permeates the network and is absorbed by the policy-making mechanisms of the network.

In general, the network structure suggests that the dominant coalition, and RISTEK and Timnas BBN in particular, are in positions to impact conditions for learning, but limitedly so. Together these two actors exhibit a strong influence over the network as liaisons, consultants and gatekeepers whereby, they are in positions to enhance interconnectedness between members of the network and help perpetuate the rules, norms and values necessary for policy learning. Even though non-state actors such as Sawitwatch, CGIAR and academic organizations such as ITB do reveal some knowledge brokering roles, they are eclipsed entirely by RISTEK and Timnas BBN who are revealed as much stronger as intermediaries in the network. For, cognitive and technical learning, even though these two actors are revealed as strong representatives of knowledge ties originating from the government, they are not equally strong coordinators that are needed to allow for a variety of problem perceptions and alternative generation, while perpetuating a sense of urgency about the sustainability problems associated with biodiesel production.

From this study we can see that policy network research can enhance studies of policy learning and many avenues for furthering research on learning in networks and more specifically on brokerage and knowledge ties, exist. Methods such as quantitative SNA can reveal general patterns and provide a tool for displaying a broad ‘snapshot’ of the policy learning architecture of a subsystem. Knowing the positions of policy actors and the network structure is akin to knowing the blueprint of the knowledge infrastructure and can inform us on the possibilities of learning to occur and the bandwidth within learning and policy change can take place.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Michael Howlett is the Burnaby Mountain Chair in the Department of Political Science at Simon Fraser University and Yong Pung How is the Chair Professor in the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy at the National University of Singapore. He specializes in public policy analysis, political economy, and resource and environmental policy. His articles have been published in numerous professional journals in Canada, the United States, Europe, Latin America, Asia, and Australia and New Zealand. He is the current chair of Research Committee 30 (Comparative Public Policy) of the International Political Science Association and sits on the organizing committee of the International Conference on Public Policy.

Ishani Mukherjee is a postdoctoral fellow at the Institute of Water Policy and previously at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy (LKSYPP), National University of Singapore. She is also the editor for the International Public Policy Association (IPPA). She received her PhD in Public Policy, with a focuis on Environmental Policy and was the recipient of the World Future Foundation PhD Prize for Environmental and Sustainability Research in 2014. She also received the Policy and Politics Ken Young Best Paper Award for 2015, along with her co-authors Michael Howlett and Woo Jun Jie. Widely published, her research interests combine policy design and policy formulation, with a thematic focus on policy instruments for environmental sustainability, renewable energy and energy efficiency, particularly in Southeast Asia. She worked previously at the World Bank’s Energy practice in Washington, DC on formulating guidelines and evaluating projects related to renewable energy, rural electrification and energy efficiency. She obtained her MS degree in Natural Resources and Environmental Economics from Cornell University.

Joop Koppenjan is a professor of Public Administration at the Erasmus University Rotterdam and adjunct professor at the Southern Cross University, Australia. He studies public policy, policy networks, public–private partnerships and public management, with a focus on governance, stakeholder involvement, public values and sustainability. Areas of application are infrastructure-based sectors such as transport, water, and energy, and social sectors such as social support, care, and safety.

Acknowledgement

Ishani Mukherjee would like to thank the World Future Foundation (WFF) for awarding the 2014 Phd Prize for her thesis titled Prioritizing Sustainability: Coalitions, Learning and Change Surrounding Biodiesel Policy Instruments in Indonesia, which has formed the basis of the case presented in this paper.

References

Footnotes

Recent work on policy subsystem subgroupings (Howlett, McConnell, & Perl, 2015a, 2015b; Mukherjee & Howlett, 2015) has distinguished at least three, distinguishable by which part of the policy process is most vital to members. That is, coalitions may form based on how members are preoccupied with defining the nature of a policy problem, or how they share a concentrated focus on the instruments meant to address policy problems, or how they are united based on a common politics of pushing preferred policy components (Gough & Shackley, 2001; Haas, 1992; Sabatier & Jenkins-Smith, 1993; Sabatier & Weible, 2007; Voß & Simons, 2014; Zito, 2001). This framework suggests that central actors – policy brokers – can have a significant impact on policy learning by forging or brokering knowledge-based ties between these diverse groups of actors.