Abstract

Traffic enforcement and associated penalties are essential in any successful road safety strategy. Available literature identifies both traditional and automated traffic enforcement. Ghana employs traditional traffic enforcement involving visible police officers enforcing traffic rules and regulations on the roadways. This phenomenological study explores the perceived effectiveness of police road presence as a road safety strategy in the Ghanaian context. Data for the analysis came from in-depth interviews of 42 people recruited as a convenience sample (comprising 25 commercial drivers, 12 private drivers, and five traffic police officers of the Motor Traffic and Transport Department (MTTD) of the Ghana Police Service). The study results suggest widespread driver road tactics to outwit the traffic police officers, police extortion and driver bribery (road traffic corruption), and punishment avoidance. These behaviours undermine deterrence and negate the seriousness and expected general deterrent effect of the police road presence and enforcement. This study provides an initial exploration of the effectiveness (or otherwise) of police road presence and enforcement in the context of a developing country. Additional studies are, however, needed to explore this phenomenon further.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The recent World Health Organisation (WHO) Global status report on road safety 2018 reveals that global road traffic deaths have increased from 1.25 million deaths per year to 1.35 million deaths per year since the beginning of 2016, with an estimated 50-million-person injury. Consequently, road traffic crashes are currently the 8th leading cause of death for all ages and the 1st leading cause of death for persons in the 5–29 age group (World Health Organization (WHO), 2018). The WHO report also indicates that Africa has the worst road traffic deaths (i.e., 26.6 deaths) per 100,000 people, nearly three times the European figure (9.3 deaths per 100,000 people). The current pace of global road traffic fatalities (especially in developing countries) casts doubts on our ability to achieve the road safety-related United Nations (UN) sustainable development goals (SDGs) and targets anytime soon. Mainly, target 3.6 (halve the global deaths from road traffic crashes) and target 11.2 (improving road safety in providing access to transport systems and expanding public transport).

Conventionally, the strategies and associated policy interventions to tackle road traffic deaths and injuries globally have centred on the 3Es, namely education, engineering and enforcement (Groeger, 2011; Plant et al., 2018). Enforcement is arguably the most documented of the 3Es, albeit in developed countries. Enforcement seeks to control road user behaviour (basically the “human factor” of road traffic crashes) often through preventative, persuasive and punitive measures to ensure the safe and efficient movement of traffic (Zaal, 1994). Porter (2011) identified two types of traffic enforcement: traditional and automated traffic enforcement involving evident police presence on the roadways and the use of technology to locate and apprehend traffic offenders to ensure traffic compliance. Ghana employs mainly the traditional traffic enforcement approach with police officers on major roadways designed to ensure road users (particularly motorists) adhere to traffic rules and regulations.

The classical deterrence theory has usually underpinned traffic enforcement or road policing strategies to reduce the prevalence of unsafe driving behaviours and improve road safety (Davey and Freeman, 2011; Bates et al., 2012). The classical deterrence theory “proposes that individuals will avoid offending behaviour(s) if they fear the perceived consequences of the act” (Davey and Freeman, 2011, p. 29). According to the theory, law-breaking (in this case, traffic offences) is inversely related to the certainty, severity, and swiftness of punishment. Thus deterrence can be achieved when there is a high likelihood of apprehension (i.e., certainty) and the impending punishment is both severe and swift (Bates et al., 2012, 2020). Bates et al. (2020) further argue that deterrence is likely to be minimal if motorists are not certain that their offending behaviour will be detected and punished no matter how swift and severe punishment for traffic offences are. Consistent with these views, road safety scholars rightly argue that road safety operations that increase the perceptions of apprehension certainty for unsafe, illegal driving behaviours are likely to have a positive deterrent effect on traffic offenders (Watson and Freeman, 2007).

Two main deterrence processes have been identified: specific and general deterrence (Stafford and Warr, 1993; Tay, 2005). Specific deterrence occurs when an apprehended and punished (sanctioned) individual (in this case motorist) refrains from further/future offending behaviour for fear of incurring additional punishment/sanction (i.e., the deterrent effect of a direct experience with punishment). General deterrence, on the other hand, occurs when a would-be offender (e.g., a motorist) is deterred from committing a criminal behaviour (in this case, traffic offence) because another has been apprehended and punished for the same offending behaviour (i.e., the deterrent effect of an indirect experience with punishment). It has been argued that general deterrence could also arise from using media to communicate and increase the perception of the certainty of apprehension and the impending sanctions for committing an offence (Tay, 2005; Davey and Freeman, 2011). Tay (2005) further argues that police road presence (the focus of this paper) focuses more on general deterrence while police apprehension (or what he terms “hit”) rates while on the road focus more on specific deterrence. Tay further maintains that, theoretically, general deterrence cannot be achieved without at least a minimum level of specific deterrence (Tay, 2005).

On their part, Stafford and Warr (1993) argue that the distinction between general and specific deterrence is dependent on the nature of the direct prior experience with legal punishment rather than the mere presence of such experience. Accordingly, they reconceptualised general deterrence to refer to “the deterrent effect of indirect experience with punishment and punishment avoidance”, in contrast, specific deterrence refers to “the deterrent effect of direct experience with punishment and punishment avoidance” (p. 127).

Stafford and Warr (1993) further argue that experience with punishment avoidance is likely to affect perceptions of the certainty and severity of punishment, with the perceptions of certainty of apprehension being the most affected in the case of punishment avoidance. That is, although an offence may have been committed, the offender got away with it. Although they argue that the notion of punishment avoidance is difficult to imagine because it refers to an event(s) that did not happen, yet it is contingent on an event(s) that did occur (i.e., commission of a crime or antisocial act). In this respect, Stafford and Warr (1993) argued that “it is possible that punishment avoidance possibly does more to encourage crime than punishment does to discourage it” (p. 125).

Notwithstanding, a growing body of evidence has demonstrated that sanctions (in the case of specific deterrence) and media communication of the threat of apprehension and subsequent sanctions (in the case of general deterrence) can reduce the likelihood of re-offending for traffic offences, including speeding, unlicensed driving and drunk driving. In this way, sanctions also produce desirable safety outcomes on crashes and severe injury rates and actual perceptions of apprehension certainty (Glendon and Cernecca, 2003; Elvik and Christensen, 2007).

Several authors, including Zaal (1994), Porter (2011), and Shaaban (2017), argue that the effect of traffic enforcement (i.e., road policing) and sanctions on road user behaviour are instantaneous. Porter (2011) argues that sufficient enforcement leads to risk perceptions in getting caught. As a result, Shaaban (2017) maintain that traffic enforcement and its associated sanctions are an essential road safety strategy, even though Porter (2011) and Miller et al. (2004) argue that the effectiveness of enforcement is dependent on the strength of the law enforcement activities.

However, there are counterarguments that the effect of traffic enforcement on road user behaviour and invariably on road safety is short-lived and often not effective in the long term. Available evidence suggests that there is often a reduction in compliance after the police have left the road environment. This is, however, believed to be dependent on the duration and regularity of enforcement and the frequency with which the same traffic (i.e., road user) uses the same roadway at the same time each day (Dart and Hunter, 1975; Booth, 1980). In another vein, Maroney and Dewar (1987) also strongly argue that traffic enforcement does not affect the intentions of the violator (in our case, the motorist).

Study objective

Much of the extant literature on road policing and its effectiveness as a road safety strategy are from (or situated in) developed countries (Tay, 2005; Wells, 2008; Lapham and Todd, 2012; Bates et al., 2020; McDonald et al., 2020; Nunn, 2020; Freeman et al., 2021; Truelove et al., 2021). There is little research on the topic from the context of low-and-middle-income countries (LMICs). A previous related study in the context of LMICs, Tankebe et al. (2020)’s study, examined traffic violations and cooperative intentions among some commercial drivers in Ghana, considering the role of corruption and fairness. They found that personal and vicarious corruption experiences predicted self-reported traffic laws violations and was also negatively related to the likelihood of cooperative intention. It is thus crucial that we gain a greater understanding of what is effective in LMICs especially given its safety records of consistently high preventable human/driver-induced road traffic crashes and fatalities.

Furthermore, a considerable amount of the research in this space has been quantitative in approach (Tay, 2005; Lapham and Todd, 2012; McDonald et al., 2020; Freeman et al., 2021). Using a qualitative methodology (phenomenological enquiry), the study sought to provide an initial exploration of the effectiveness of road policing and enforcement in the Ghanaian context. Expressly, this study explored whether police road presence (which is more aligned to general deterrence) is an effective means of deterring traffic offending behaviour(s). The study takes a dual perspective on police road presence (general deterrence) effectiveness from both motorists and traffic police officers. Firstly, the study explores motorists’ perception of police road presence, their attitudes and behaviour towards police road presence (lived experiences) and perceived effectiveness of road policing as a road safety strategy. Additionally, the study explores traffic police officers’ knowledge of motorists’ attitudes and behaviour towards police road presence and their perceptions of the effectiveness of their road activities on road safety.

The remaining part of the paper proceeds as follows: the next section discusses road policing and enforcement in Ghana, followed by a description of the study methodology and results and discussion. The last aspects of the paper present the practical implications, study limitations and areas for further studies, and conclusion.

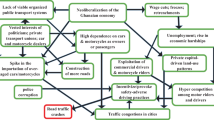

Road policing and enforcement in Ghana

There have been consistent increases (12–15% annually) in road traffic fatalities in Ghana since 2008. For instance, there were 2084 traffic deaths in 2016 alone, with an additional 10,438 suffering various degrees of injuries (National Road Safety Commission, 2017; Boateng, 2021). Road trauma is one of the top 10 leading causes of death in Ghana, with a socio-economic cost of about 1.6% of GDP (Afukaar et al., 2003; Ackaah et al., 2008; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019). Aberrant driving behaviours such as driving above posted speed limits, reckless overtaking, and drunk and fatigued driving has been established as the leading causes of road crashes in Ghana (Ministry of Transport and NRSC, 2012; GhanaWeb, 2019, cited in Boateng, 2021).

The country’s countermeasures to reduce road traffic crashes and fatalities have mainly prioritised road policing and enforcement, targeting speeding, seatbelt and helmet use, drunk driving, unlicensed driving, and other aberrant driving behaviours (National Road Safety Commission, 2017; Boateng, 2021). Traffic police officers are usually deployed daily to sections of significant roadways (mainly crash-prone roads) during morning, afternoon and evening hours to check motorists (to achieve general deterrence).

Since July 2019, there has been a growing effort on the part of the Motor Traffic and Transport Department (MTTD) of the Ghana Police Service and Citi TV/FM (a media house in Ghana) to crack down on road traffic violations and other acts of indiscipline on the country’s roads in what is dubbed “War Against Indiscipline (WAI)” driving (Ghana Police Service, 2019; cited in Boateng, 2021). This operation has seen traffic police officers and reporters from Citi TV monitor motorists’ traffic behaviour. These operations have seen many drivers arrested and prosecuted for various road traffic violations in the country, with financial benefits to the state; about GH¢258,000 (close to US$5000) were realised in the first two days of operation WAI from the prosecution of some 500 drivers for various traffic violations (Boateng, 2021).

The MTTD has also mounted 3000 intelligent surveillance cameras nationwide at significant traffic intersections to monitor and apprehend traffic offences for possible prosecution (Myjoyonline.com, 2021).Footnote 1 It is reported that the monitoring and surveillance system have captured over 2000 cases of traffic violations in barely two months of its installation. The Traffic Monitoring and Surveillance Centre is housed at the Police Headquarters in Accra, the capital city (3News, 2021). The centre collaborates with the Driver and Vehicle Licensing Authority (DVLA) to retrieve details of vehicles captured by the system and identify the vehicle owners for prosecution (Myjoyonline.com, 2021).

Methodology

This study utilised a phenomenological research methodology to explore the lived experiences (Creswell, 2007) (in this case, the opinion, attitude and behaviour) of motorists’ (mainly drivers) towards police road presence and its perceived effectiveness as a road safety strategy. It also explores traffic police officers’ knowledge of motorists’ attitudes and behaviour towards traffic enforcement and their opinion on the road safety impact of their road presence or activities to validate the drivers’ claims and establish common beliefs and opinions on the subject. The study explored these issues based on anecdotal evidence. Phenomenological enquiry offers the opportunity to explore, learn, and understand social reality from social actors’ lived experiences, motivations and actions (Lester, 1999; Creswell, 2007, 2014; Dotse et al., 2019).

Participants and procedure

The study involved 42 people recruited in Accra as a convenience sample (25 commercial drivers, 12 private drivers and five traffic police officers from the MTTD). The participants (particularly the commercial drivers) were mainly males, aged 18–65 years (mean age = 47 years) with 4–38 years of driving experience. Most drivers undertake regular long-distance trips (more than 251 km per day) and regularly encounter traffic police officers. It emerged that the commercial drivers were more likely to be older, with more driving experience and meet traffic police officers more frequently than the private drivers.

A research assistant interviewed (using a semi-structured interview guide to allow for probes) the commercial drivers at Kwame Nkrumah Circle and Kaneshie bus terminals (Fig. 1A in the appendix shows the map of the study sites). Kwame Nkrumah Circle and Kaneshie house some popular bus terminals and intercity, long-distance buses in Accra. The other participants (i.e., private drivers and traffic police officers) were recruited through personal contacts and were interviewed in their residences and offices. Verbal consents were obtained from the participants before each interview; each interview session lasted between 10–15 min. Table 1 presents key questions asked during the interviews based on pre-determined themes. The interviews were conducted in April and May 2020. Data collection involving the drivers was done to the point of saturation to ensure the study results’ validity (i.e., trustworthiness) (Sandelowski, 1995; Charmaz, 2000). However, the perspectives of five traffic police officers, based on convenience, were sought to deepen some aspects of the findings from the drivers.

Using the same instrument (semi-structured interview guide) and probes (usually comments/insights from previous interviews—i.e., “member check interview”) helped ensure the integrity of the responses (Doyle, 2007 cited in Birt et al., 2016). In the member check interview protocol, “the transcript of the first interview foregrounds the second interview during which the researcher focuses on confirmation, modification, and verification of the interview transcript” (Birt et al., 2016, p.1805).

Analysis

Most of the interviews were done in Twi (a popular local dialect) and later transcribed into English. Data coding and analysis used the deductive thematic analytic framework based on pre-determined themes arising from anecdotal evidence. The Atlas.ti 8 software was employed for data coding following a three-stage approach: open coding (assigning codes to words and phrases in the transcripts); axial coding (grouping codes into (sub)categories), and selective/theoretical coding (relating the codes and (sub)categories to their respective broader parent themes) (Charmaz, 2006). The following were the themes and sub-themes generated: driver reaction to police road presence (how drivers become aware of police road presence; how drivers communicate to caution other motorists approaching police checkpoints; and driver reaction upon being alerted of police road presence); driver perspective on the effectiveness of police road presence on driver behaviour and road safety; and police perspective (rationale for police road presence and effectiveness of police road presence on driver behaviour and road safety).

Results and discussion

This study sought to provide an initial exploration of the perceived effectiveness of road policing and enforcement (which is more aligned to general deterrence) in the Ghanaian context. The study takes a dual perspective on the perceived effectiveness of police road presence from both motorists and traffic police officers.

Driver reaction to police road presence

Three (3) interrelated sub-themes were generated from this central theme, bearing on (a) how drivers become aware of police road presence during their trips, (b) how drivers communicate to alert/caution other motorists approaching police checkpoints, and (c) driver reaction upon being alerted/cautioned of police road presence.

Driver awareness of police road presence during trips

As noted in the following comments, the study observed that drivers become aware of police road presence mainly through signals and cautions they receive from other motorists who had already encountered the police on the roadway and self-anticipation (arising from their past encounters with the police at section(s) of the road):

First, I know the police will be at the post by the route I am driving. Secondly, colleague drivers will always alert me if the police make an unexpected appearance on the road (40 years old, Male, Commercial driver).

There may not always be signs indicating a police checkpoint ahead, but we know where the police mount their checkpoints, so we slow down as we get closer to these locations (54 years old, Male, Commercial driver).

A 59-year-old commercial driver also revealed that:

There are so many ways that we get to know. For instance, those of us who have been on the road for so many years know where the police checkpoints are, so we prepare as we get close to the checkpoints; sometimes, we ask from other drivers.

Driver communication to alert/caution other motorists approaching police checkpoints

As opined by some participants below, drivers flash (in quick succession) their vehicle headlights and point their index fingers (hand gestures) toward the ground as an indication that there is a police checkpoint ahead (i.e., the police are on the road). The study observed that these gestures are “familiar” to drivers (at least all the surveyed drivers understood these gestures). For instance, a 38-year-old commercial driver revealed that:

Even though we know where the police checkpoints are, sometimes the police change their locations. Once we get to know their new location, we signal other drivers with flashes of the headlights and the index finger pointing to the ground to indicate that the police are in the direction they are heading.

Other participants revealed that:

The incoming driver will point his index finger to the ground as a way of asking whether there is a police barrier (i.e., checkpoint) ahead, then you tell him if there is a barrier ahead. But if there is no barrier, you use your hand to signal him to go on. Also, we use the headlight to signal to oncoming drivers that there is a police barrier ahead, especially when the person did not ask about it. Still, you want to notify the person (57 years old, Male, Commercial driver).

Oh, since driving is our job, we understand its “language”. Let’s say a fellow driver (whether known or unknown) meets you, point the index finger to the ground and flash the headlight; it implies “danger ahead” in this context, police checkpoint ahead (50 years old, Male, Commercial driver).

Figure 1 confirms the narratives above by illustrating the common ways drivers communicate police road presence to other motorists through a word cloud.

The data above reveals that the flashing of the vehicle headlight often in quick succession and pointing the index finger towards the ground are essential gestures to communicate police road presence. It emerged that these gestures are common and easily understood by motorists (a “familiar language” to motorists). An earlier study by Hamed et al. (1998) also reported headlights and hand signals among minibus drivers in Jordan to communicate police road presence. However, a recent study has revealed that motorists engage in this behaviour (continually looking out for police road presence) because of the often unexpected, unscheduled police checkpoints (Dotse et al., 2019).

Driver reaction upon being cautioned about police road presence

The data also revealed that drivers “adapt” their driving behaviour when cautioned about police checkpoints ahead. Most of the drivers (mainly commercial drivers) indicated that they “prepare” as they approach police checkpoints by reducing their speed, wearing their seatbelt, and organising their driving licence and other relevant documents (e.g., vehicle insurance) for possible inspection. Figure 2 presents a word cloud of the typical driver responses to police road presence.

Most drivers revealed bribing the police (willingly or coerced) by giving them monies (usually between GHS 2 and GHS 5) concealed in leaflet or licence cover. Commercial drivers indicated that this practice had become the norm, the failure of which often resulted in unnecessary delays and the threat of prosecution for traffic offences (albeit minor). It is also usually the case that “at-fault drivers” resort to bribing the police to avoid scrutiny and the associated delays (e.g., driving licence and vehicle and roadworthy inspections) and the threat of prosecution for road traffic offences as presented below.

First, you reduce your speed and put things in order as you approach the checkpoint. Even though you may have genuine documents yet, they will not allow you to go if you do not give them money (27 years old, Male, Commercial driver).

Sometimes it depends on the MTTD team on the road; if the team is not strong, I will just put money in my licence cover and hand it over to them. However, if the unit is strong and I am at fault, I can hand over my passengers to another car and stand by until the police leave the road, and then I continue my journey (34 years old, Male, Commercial driver).

As revealed above, when so cautioned, the drivers adapt their behaviour by appearing to be safety-conscious (i.e., reducing their speed, wearing a seatbelt and organising the relevant documents for possible police inspection). Some of the drivers reported often bribing traffic police officers (often willingly) at these checkpoints to avoid scrutiny and the occasioned delays and possible punishment in the case of being at fault. Often, these delays are believed to constitute a financial loss to commercial drivers (i.e., loss of sales), so they do anything possible to avoid the same (Dotse et al., 2019). In essence, commercial drivers have learnt, and try as much as possible, to avoid punishment (Porter, 2011) by engaging in road tactics and bribery. Previous studies, including Dotse et al. (2019) and Tankebe et al. (2020), corroborate the study finding that motorists in Ghana (mainly commercial drivers), in most cases, attempt to bribe traffic police officers to escape/avoid punishment. Anecdotal evidence suggests that this “bribe-giving behaviour” (bribery) is typical among commercial drivers as they are often the most likely of all motorists to be stopped by traffic police officers for various traffic offences (violations and lapses), including overloading, overspeeding and driving without proper documentation (Dotse et al., 2019; Boateng, 2020; Tankebe et al., 2020). This situation is worrying given the body of evidence that suggests that punishment avoidance (i.e., not being punished for committing an offence) means that drivers will continue to engage in illegal behaviours (Stafford and Warr, 1993; Armstrong et al., 2018; Bates and Anderson, 2021).

It is also worth noting that drivers are also coerced into giving bribes (as revealed by some respondents above). Police road extortion seems to have been institutionalised to the point that traffic police officers often use the slightest traffic offence of motorists as an opportunity to extort monies from them. With this being the case, it appears that some drivers are only playing by the “rules of the game” (i.e., institutionalised extortion) by giving bribes often against their will. Tankebe and colleagues rightly note that at-fault drivers appear to be vulnerable to police extortion (Tankebe et al., 2020).

The study suggests that the drivers solicit and give information about police checkpoints and engage in road tactics (in response to police road presence) and bribery consistent with recent local-context studies (Dotse et al., 2019; Boateng, 2020; Tankebe et al., 2020).

Driver perspectives on the effectiveness of police road presence on driver behaviour and road safety

The second central theme reveals drivers’ (both commercial and private) assessment of the perceived effectiveness of the police road presence on driver behaviour and road safety. It is crucial to indicate that this assessment revealed mixed feelings. On the one hand, as some drivers (mostly private drivers) argued below, police road presence ensures road users’ benefit as it helps enforce the road traffic rules and regulations and deter wrongdoing on the road.

What I think about the police is that they go to the highway to check drivers to follow road traffic regulations. Some drivers over-speed and others drink and drive, so the police mainly patrol the roads to check all of these behaviours to prevent a crash (56 years old, Male, Private driver).

Yes, their presence affects us because as a driver, whenever you see the police on the road, you are compelled to conform (38 years old, Male, Private driver)

Yet another participant reasoned that:

It influences me to be very careful on the road. The police have the speed gun to detect your speed regarding overspeeding. They also have a device (alcohol breath analyser) to put in your mouth to determine your blood alcohol content. They also check whether you have your seatbelt on, fire extinguisher and the rest. These influence me to engage in good driving practices to prevent a crash (40 years old, Male, Private driver).

Notwithstanding, many of the commercial drivers sampled had contrary, negative opinions on the effect of police road presence on driver behaviour and road safety. Most of them maintain that the police are on the road to extort monies from motorists, as is evident from the comments below.

I’m very happy you’ve asked me this question. As we are all aware, the presence of the police on the highway is to ensure law and order, but our current crop of police officers do not act according to their mandate. They are preoccupied with money-bribes. Anytime I set off on a journey, I make sure I have their money ready (50 years old, Male, Commercial driver).

They do nothing to ensure road safety. Their motive is to collect monies from drivers; this is our major issue with the police on the road. This is because whether you have the correct vehicle documents or not, they (police) will still take money (40 years old, Male, Commercial driver).

Moreover, this comment by a 46-year-old commercial driver is very revealing:

Actually, their presence prompts us to conform to the road regulations, but their actions do not portray that. For example, I’m not supposed to travel with a worn-out tyre, but right now, after talking to you, I will be going to Kumasi, and once I have my GH₵ 5, they won’t even care or let alone check my tyres. Road safety is, however, drivers’ responsibility; the police do not help in any way.

A possible explanation for this (negative) assessment by commercial drivers may be due to their negative encounters (including police extortion or self-initiated bribery) with traffic police officers, as reported by recent local studies (Beek, 2017; Dotse et al., 2019; Boateng, 2020; Tankebe et al., 2020). Tankebe et al. (2020), for instance, revealed that 82% of their study participants (commercial drivers in Ghana) had ever been stopped and interrogated by traffic police officers, with 51% of these stops involving payment of bribes to the officers. As Foltz and Opoku-Agyemang (2015) rightly note, extortion or bribery is often the consequence of police suspicion of traffic violations by drivers. A comment by a Police Lance Corporal (as reported by Beek) is informative in this regard: “Every car has an offence. We just want to do the right thing. They make up their mind and give you money. I wouldn’t call it a bribe. It is just a dash (i.e., gift). It’s not perfect” (Beek, 2017, p. 236).

From a broad perspective, road traffic corruption (police extortion and driver self-initiated bribery) seems to negate the supposed safety benefit of traffic enforcement in respect of ensuring discipline on the road and compliance with traffic laws. The drivers’ comments above also seem to suggest, covertly, some kind of reciprocityFootnote 2 (reciprocal relationship) between traffic police officers and drivers, such that giving bribes helps a driver escape/avoid police scrutiny and the possible threat of prosecution even if at fault. Beek (2017) also mentions ‘reciprocal traffic officers’ who “show care for drivers’ wellbeing, and avoid discriminatory stops of drivers, yet choose not to enforce the law on account of extra-legal considerations” (p. 236). Such traffic police officers tolerate drivers’ traffic violations for which the drivers show appreciation, in what Beek (2017) describe as “I scratch your back and you scratch mine” (p. 244).

Tankebe et al. (2020) opine that such drivers will be inclined to disobey traffic laws the more traffic corruption persists. The phenomenon has a debilitating effect on the effectiveness of traffic enforcement and the police’s activities on the road. A commercial driver’s comment is informative about the negative impact of road traffic corruption on road user behaviour and road safety generally: “Actually, their presence prompts us to conform to the road regulations, but their actions do not portray that. For example, I’m not supposed to travel with a worn-out tyre, but right now, after talking to you, I will be going to Kumasi, and once I have my GH₵ 5, they won’t even care or let alone check my tyres. Road safety is, however, drivers’ responsibility; the police do not help in any way”. On the back of this, Miller et al. (2004) opine that diminishing the apparent seriousness with which traffic offences are addressed by traffic police officers serve to decrease deterrence with a devastating general effect on road safety.

Police own perspectives on the effectiveness of their road presence on driver behaviour and road safety

The study also sought the traffic police officers’ assessment of the emerging issues from the drivers’ interviews.

The rationale behind police road presence/checkpoints

It emerged from the data that police road presence or checkpoints aim to enforce road traffic rules and regulations to ensure road safety for all road users. The following comments from some of the traffic police officers are worth noting:

Our motive is to ensure driver-pedestrian discipline and the safety of everyone onboard the vehicle and to educate road users on the offences that will incur the wrath of the state. The police are there because of the populace; we are there because of the driver; and the passenger. That is why we usually go in the daytime so that the public can assess our activities, demeanour, and what we do on the road (41 years old, Male, Traffic Police Officer).

The main aim is to ensure road users (particularly motorists) comply with traffic rules and regulations, that they have their licence to operate the vehicle, that the car is roadworthy and adequately insured, and so on. We are there also to take passengers’ concerns (51 years old, Male, Traffic Police Officer).

The data also revealed that the police are not oblivious of drivers’ road tactics and strategies in response to police road presence or activities. As illustrated below, the traffic police officers indicated that they mostly conduct random road checks and audits to counteract these tactics.

We usually vary our location. We travel along the roadway and choose our positions randomly. We are not stationary at a particular place always. Our strategy is to outwit the drivers (54 years old, Male, Traffic Police Officer).

Our measures are very detailed. We try to avoid the so-called driver intelligence by conducting our road checks randomly. But better still, we go to different posts to prevent drivers from easily predicting our checkpoints (40 years old, Female, Traffic Police Officer).

The study observed that police road presence aims at regulating road users and enforcing traffic laws regarding speeding, seatbelt use, drunk driving and driving without proper documentation (especially with the recent WAI operations). Previous studies have revealed that police road presence effectively enforces these specific traffic behaviours (Soole et al., 2009; Davey and Freeman, 2011; Soole, 2012; Bates, 2014).

Dotse et al. (2019)’s study reveals that traffic police officers occasionally adopt “strange” strategies, including mounting random, unscheduled road checkpoints to outwit driver road tactics. Even though these extreme strategies may be well-intended, they defeat the essence of the police being “occasions” (Mattaini, 1996). Being visible (either standing or sitting in a parked car) on the roadway in itself will have (or has) enough (general) deterrent effect on road users (Porter, 2011).

From a broader perspective, the modus operandi of some traffic police officers, including the perceived institutionalised extortion on the roadways and mounting random, unscheduled road checkpoints (as discussed above), raises the issue of how procedurally just and fair their traffic enforcement strategies are. Procedural justice focuses on the perceived fairness of police procedure(s) to arrive at decisions and the associated treatment given during the decision-making process, often linked to police legitimacy and the cooperation and compliance they receive from the public (Tyler, 2006).

The literature identifies four principles of procedural justice: voice, neutrality, respect and trustworthy motives (Bates, 2014; Tudor-Owen, 2021). Voice, for instance, entails allowing people (in this case, drivers) to communicate their views during their encounters with the police (Bates, 2014). The study findings reveal that this aspect is mostly lacking in police-driver encounters. Drivers hardly have a say or cannot explain their side of the issues when apprehended. A previous study in the UK suggests that drivers prefer to have, at least, an interaction with traffic police officers when they offend (Wells, 2008).

Respect also connotes the absence of impoliteness and receiving fair and suitable treatment from the authorities (Bates, 2014). The study reveals that most drivers are not treated fairly during their encounters with traffic police officers on the roadways. For instance, the study revealed the desperation most drivers, mainly commercial drivers, feel when dealing with the traffic police officers who have institutionalised extortion such that even if a driver has the proper documentation and is obeying the traffic rules and regulations, a corrupt officer will find the flimsiest excuse to extort money regardless. Many of the cases of police scrutiny and associated delays and threats of prosecution could easily be settled with caution (especially in the case of first-time offenders or minor lapses) and education. That way, the motorist leaves the scene with something positive that could subsequently engender safer traffic behaviour. A recent study (Chua et al., 2017) found that issuing cautions or warnings (police cautions) to drivers have a similar deterrent effect as punishment. They found that the cautioned drivers were 1.3 times less likely to speed (i.e., re-offend) in the subsequent week, with harsh caution/warning the more practical (1.6 times more effective).

Related to trustworthy motives, individuals (in our case, drivers) should perceive that the authorities (i.e., the traffic police officers) have their wellbeing at heart. Further, the authorities are genuinely trying to do their best for them (Goodman-Delahunty, 2010; Murphy et al., 2013; Murphy and Barkworth, 2014, cited in Bates, 2014) without ulterior motives (Tudor-Owen, 2021). The principle of trustworthy motives was largely missing from the drivers’ reported encounters with the traffic police officers. Most drivers maintain that the traffic police officers go to the roadways to engage in acts which inure to their benefits such as extorting money from drivers and not to benefit the drivers and the travelling population. The comment of a 40-year commercial driver reported in this study is thus worth reiterating (“they do nothing to ensure road safety. Their motive is to collect monies from drivers; this is our major issue with the police on the road”).

Evidence in the field suggests that people are more likely to consider the police as legitimate if their actions are procedurally fair and with trustworthy motives (Murphy, 2009; Goodman-Delahunty, 2010; Sargeant et al., 2012; Murphy et al., 2014, cited in Bates, 2014). Wells (2008) and Bates (2014) have suggested that fairness is essential for drivers, particularly concerning speeding offences. Traffic police officers are expected to be fair when dealing with drivers; otherwise, they risk losing future driver cooperation and compliance (Bates, 2014; Bradford, 2014). The work of Bates (2014) offers other exciting insights on the importance of procedural justice in a road safety policing context for the interested reader.

Effectiveness of police road presence on driver behaviour and road safety

On this sub-theme, the sampled traffic police officers were unequivocal on the effect of their road checkpoints and presence on driver behaviour and ultimately on road safety. They maintain that their checks effectively regulate driver traffic behaviour and thus can be credited for reducing road traffic crashes on various sections of the road they operate. The comments below illustrate these points.

It is very effective because it reduces road crashes. When the drivers see us, they reduce their speed and conduct themselves well not to attract any punishment (40 years old, Female, Traffic Police Officer).

Yes, to me, our road presence is vital; for instance, if you study the period(s) of most road crashes, you will realise that these crashes often occur when we are not on the highway. So, you have it mainly happening at night when we don’t operate, so I believe it serves the intended purpose (51 years old, Male, Traffic Police Officer).

On the overall effect on road safety, some traffic police officers argued that:

We can help reduce the frequent road crashes which promote road safety (41 years old, Male, Traffic Police Officer)

Most drivers fear police officers on the highway; the moment they see you, they begin to do the right thing or conform. Therefore, our presence posits a positive effect on road safety. Our presence makes them sober when driving (33 years old, Male, Traffic Police Officer).

A preponderance of the evidence suggests that traffic enforcement reduces unsafe traffic behaviours and outcomes (i.e., crashes and casualties). For instance, previous studies including Council (1970), Cooper (1974), Joscelyn et al. (1971), Porter (2011), and Shaaban (2017) argue that traffic enforcement has immense instantaneous positive safety outcomes in terms of reducing traffic crashes and related fatalities and promoting conforming driving behaviour consistent with the comments above. Wells et al. (1992) found that traffic enforcement reduced crashes by 6% and injury crashes by 16% in Binghamton, New York. Given this and many others, Bates (2014) notes that traffic policing is an important programme to alter the behaviour of road users (particularly motorists). Even though the study findings suggest that police road presence has a general deference effect on drivers, further studies are needed to establish the actual safety benefits of police road presence on crash frequency and injury severity in the Ghanaian context.

Practical implications

As Zaal (1994) and Bates et al. (2020) argued, any traffic enforcement’s success depends on its ability to create a meaningful deterrent threat to road users and the certainty of apprehension. As reported in this study, Ghana’s current traffic enforcement regime suggests the need to explore practical strategies to enforce and maintain road user (particularly motorists’) discipline to ensure road safety. This proposition is supported by the previous findings that traffic enforcement generally does not affect the intentions of the motorist (Maroney and Dewar, 1987) nor does it teach the behaviour being targeted (Daniels and Daniels, 2004), but only suppresses undesirable behaviour temporarily (i.e., it teaches avoidance behaviour) (Skinner, 1953). This implies that, for example, punishing a driver for not wearing a seatbelt will not necessarily increase seatbelt use as a habit; instead, some other behaviour such as wearing the seatbelt only when a police officer is present but removing it afterwards may become the norm (Porter, 2011). Similarly, Daniels and Daniels (2004) maintain that a driver does not learn to drive more slowly, but instead learns to avoid punishment by driving slower when apprehension is higher. For instance, in Stradling et al. (2005)’s study, drivers self-reported slowing down only when they encountered speed-enforcement cameras, but otherwise continued to speed. Thus, any effective traffic enforcement strategy should be able to create or facilitate new, desirable, lasting safe behaviours rather than avoidance behaviours or punishment avoidance.

Beyond the police being present on the roadways as “occasions” (as is currently the practice), the study findings justify and advance the following practical considerations for long term deterrent effects:

Firstly, the study reported widespread incidents of road traffic corruption (institutionalised extortion and bribery). Road traffic corruption seems to negate the seriousness of traffic enforcement activity. Once that becomes the case, as it is currently, traffic enforcement will no longer elicit the deterrent effect it is supposed to achieve, with serious implications for discipline on the roadway. This will also have repercussions for respect for the authority of the traffic police officers. Motorists will no longer be deterred from traffic violations knowing they can bribe their way out of trouble or possible prosecution (i.e., punishment avoidance). With that said, it is imperative for the relevant authorities to monitor the activities of the traffic police officers and sanction corrupt and recalcitrant officers accordingly. The media and the Police Intelligence and Professional Standards (PIPS) Bureau of the Ghana Police Service has essential roles to play in this regard. As the fourth estate of the realm in society, the media can draw attention to and report misconducts and corrupt road practices of traffic police officers (i.e., name and shame corrupt traffic police officers) similar to the WAI. Similarly, as the quality control unit of the Ghana Police Service, PIPS are mandated to promote professionalism and check unscrupulous practices of personnel of the service. Regular orientation of traffic police officers to be professional, trustworthy and procedurally just in their dealings with the driving population will go a long way to curb the institutionalised extortion on the road.

Furthermore, introducing other technology-driven traffic enforcement strategies (aside from the recently installed surveillance cameras), such as traffic police officers wearing “body cameras” to film their operations with motorists, can also help promote discipline and procedural justice. This move could equally help ensure motorists conform to traffic rules and regulations. This way, both the bribe-giver and bribe-taker will be deterred from the act.

Lastly, the study also observed widespread incidents of driver road tactics mainly in response to police road presence and the corresponding unscheduled, random police road checks and audits. From a broader perspective, these driver road tactics and countermeasures from the traffic police officers reflect deep underlying mistrust between these two stakeholders. This finding presents two possible avenues for policy and practice. Firstly, the result suggests an urgent need to educate motorists to understand and appreciate traffic enforcement (police road presence) is for their collective benefit. Once motorists/road users perceive the traffic police officers as being there for their wellbeing (i.e., trustworthy and without ulterior motives), they will have a positive attitude towards the police presence on the road.

Additionally, there is also the need to reorient the traffic police officers on traffic enforcement, which is to elicit conformity to the traffic rules and regulations and deter traffic violations. The current perspectives on traffic enforcement in the traffic safety literature support deploying positive reinforcement (R+) interventions, rather than mere punishment or threat of prosecution, to effect traffic behaviour change. R+ interventions are ideal for creating lasting behaviour change (Daniels and Daniels, 2004). It is the case that people work for things they want (e.g., freedom to speed to get to places quickly), and such a motivation may be more potent than the motivation to avoid getting caught (negative reinforcement, R−). R+ interventions such as rewards or incentives (a form of token reinforcers) have been demonstrated to be a good traffic management tool for promoting desirable traffic behaviour (Elman and Killebrew, 1978; Johnston et al., 1994; Ettema et al., 2010). For instance, Ettema et al. (2010) observed that motorists responded to incentives by shifting their car trips to before and after peak periods. These strategies will enhance the seriousness of the traffic enforcement activity and the integrity and authority of traffic enforcement, and safer traffic behaviour by motorists.

Study limitations and areas for further studies

The present study has a couple of strengths, including being conducted in an under-researched setting (an LMIC), applying a qualitative methodology, and incorporating the views of traffic police officers that are not frequently researched. A more significant proportion of available research in the field is quantitative in approach and situated in developed countries.

A limitation of the study is the fact that it did not target specific traffic violations or offending behaviours (as other studies have) but, more generally, driver traffic behaviour in response to police road presence and how effective this traffic enforcement strategy is serving its intended purpose(s) in the Ghanaian context. This notwithstanding, future studies should target specific traffic violations such as speeding, non-use of seatbelt and driving without proper documentation (which are often the focus of traffic enforcement in Ghana) and examine how police road presence affect these individual behaviours in our context.

Moreover, the study sample was male dominated. Only one female (a traffic police officer) participated in the study. The male dominance reflects the male domination of the driving population of Ghana (particularly of the commercial driving profession) (Dotse et al., 2019). Added to this is the comparatively smaller number of traffic police officers sampled for the study. Further studies involving more traffic police officers are needed to explore their perspectives on driver road tactics, road traffic corruption and the deterrent effect(s) of police road presence.

There is also the need to study how the behaviour of traffic police officers affect traffic enforcement activity. Previous studies, including Porter (2011), have even recommended studying traffic enforcers’ driving behaviours. This is against the backdrop that traffic enforcers should be role models for safe behaviours. The study results already posit a possible positive direction about the relationship between the actions and inactions of the traffic enforcer and the effectiveness of the traffic enforcement activity. However, further research will establish the actual impact in more concrete terms.

Conclusion

The study results suggest widespread driver road tactics to outwit the traffic police officers. There are also incidents of road traffic corruption and associated punishment avoidance which undermines deterrence and negates the expected general deterrent effect of the police road presence and enforcement. The study provides an initial exploration of the effectiveness or otherwise of police road presence in the context of a developing country. Further studies are, however, needed to explore this phenomenon comprehensively.

Data availability

The dataset generated during the study is available upon request from the author.

Notes

Myjoyonline is an online news portal of the Multimedia Group, operators of Joy FM, Joy Prime, Joy News and other media outlets in Ghana. The Multimedia Group is the largest independent commercial media and entertainment company in Ghana (www.multimediagroup.com).

Road corruption/bribery has become a ritual or obligation drivers perform whether guilty or not. However, whereas the guilty willingly bribe, the innocent driver is often apprehensive about bribing but end up doing it anyway for future sake. The positive side of paying bribes is the relationship the drivers build with the traffic police officers, which inures to their benefit in times of trouble (reciprocity). Interestingly, the drivers regularly meet the same police officers at the same roadway spots, which makes it more exciting and tempting. This is not to say that every driver prefers to pay bribes.

References

3News (2021) Over 2,000 offences captured by Ghana Police’s new traffic monitoring cameras | 3NEWS. https://3news.com/over-2000-offences-captured-by-ghana-polices-new-traffic-monitoring-cameras/

Ackaah W, Afukaar FK, Agyemang W, Debrah EK (2008) Socio-economic cost of road traffic accidents in Ghana. J Build Road Res Inst 11:39–44

Afukaar FK, Antwi P, Ofosu-amaah S (2003) Pattern of road traffic injuries in Ghana: implications for control. Inj Control Saf Promot 10(1):69–76

Armstrong KA, Watling CN, Davey JD (2018) Deterrence of drug driving: the impact of the ACT drug driving legislation and detection techniques. Transp Res Part F 54:138–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.TRF.2018.01.014

Bates L (2014) Procedural justice and road policing: is it important? In: Truong J, Tierney P (eds.) Proceedings of the Australasian road safety research, policing & education conference

Bates L, Anderson L (2021) Young drivers, deterrence theory, and punishment avoidance: a qualitative exploration. Policing 15(2):784–797. https://doi.org/10.1093/police/paz075

Bates L, Anderson L, Rodwell D, Blais E (2020) A qualitative study of young drivers and deterrence based road policing. Transp Res Part F 71:110–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2020.04.003

Bates L, Soole D, Watson B (2012) The effectiveness of traffic policing in reducing traffic crashes. In: Prenzler T (ed) Policing and security in practice: challenges and achievements. Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 90–109

Beek J (2017) Money, morals and law: the legitimacy of police traffic checks in Ghana. In: Beek J, Göpfert M, Owen O, Steinberg J (eds) Police in Africa: the street level view. Oxford University Press, pp. 231–248

Birt L, Scott S, Cavers D, Campbell C, Walter F (2016) Member checking: a tool to enhance trustworthiness or merely a nod to validation? Qual Health Res 26(13):1802–1811. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732316654870

Boateng FG (2020) “Indiscipline” in context: a political-economic grounding for dangerous driving behaviors among Tro-Tro drivers in Ghana. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 7(8):1–5. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-0502-8

Boateng FG (2021) Why Africa cannot prosecute (or even educate) its way out of road accidents: insights from Ghana. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 8(1):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00695-5

Booth WL (1980) Police management of traffic accident prevention programs. Charles C. Thomas

Bradford B (2014) Policing and social identity: procedural justice, inclusion and cooperation between police and public. Polic Soc 24(1):22–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/10439463.2012.724068

Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (2019). CDC in Ghana. Centres for Disease Control and Prevention

Charmaz K (2000) Grounded theory: objectivist and constructivist methods. In Denzin NK, Lincoln YS (eds.) The Handbook of Qualitative Research, 2nd edn. Sage Publications, Inc., pp. 509–535

Charmaz K (2006) Constructing grounded theory: a practical guide through qualitative analysis. Sage

Chua PY, Liang A, Kok Y, He R (2017) Can ShortWarning messages reduce speeding behaviour? Insights from A/B testing. Eur Sci J 13(5):494. https://doi.org/10.19044/esj.2017.v13n5p494

Cooper PJ (1974) Effect of increased enforcement at urban intersections on driver behaviour and safety. In: Cooper PJ (ed.) Effectiveness of traffic law enforcement. Delevin, Cather and Co, of Canada

Council FM (1970) A study of the immediate effects of enforcement on vehicular speeds. Council FM

Creswell JW (2007) Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among the five approaches, 2nd edn. Sage Publications Ltd

Creswell JW (2014) Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches, 4th edn. Sage Publications, Inc

Daniels AC, Daniels JE (2004) Performance management: Changing behaviour that drives organisation effectiveness, 4th edn. Performance Management Publications

Dart OK, Hunter WW (1975) Evaluation of the Halo effect in speed detection and enforcement. Transp Res Rec 609:31–33

Davey JD, Freeman JE (2011) Improving road safety through deterrence-based initiatives: a review of research. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J 11(1):29–37

Dotse J, Nicolson R, Rowe R (2019) Behavioral influences on driver crash risks in Ghana: a qualitative study of commercial passenger drivers. Traffic Inj Prev 20(2):134–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/15389588.2018.1556792

Elman D, Killebrew TJ (1978) Incentives and seat belts: changing a resistant behaviour through extrinsic motivation. J Appl Soc Psychol 8:72–83

Elvik R, Christensen P (2007) The deterrent effect of increasing fixed penalties for traffic offences: the Norwegian experience. J Saf Res 38(6):689–695. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsr.2007.09.007

Ettema D, Knockaert J, Verhoef E (2010) Using incentives as traffic management tool: empirical results of the “peak avoidance” experiment. Transp Lett 2(1):39–51. https://doi.org/10.3328/TL.2010.02.01.39-51

Foltz JD, Opoku-Agyemang KA (2015) Do higher salaries lower petty corruption? A policy experiment on West Africa’s highways, IGC Working Paper

Freeman J, Parkes A, Truelove V, Lewis N, Davey JD (2021) Does seeing it make a difference? The self-reported deterrent impact of random breath testing. J Saf Res 76:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsr.2020.09.013

Glendon AI, Cernecca L (2003) Young drivers’ responses to anti-speeding and anti-drink-driving messages. Transp Res Part F 6(3):197–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1369-8478(03)00026-3

Groeger JA (2011) How many E’s in road safety? In: Porter BE (ed.) Handbook of traffic psychology. Academic Press, pp. 3–12

Hamed MM, Jaradat AS, Easa SM (1998) Analysis of commercial minibus accidents. Accident Anal Prev 30(5):555–567. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0001-4575(98)00021-9

Johnston JJ, Hendricks SA, Fike JM (1994) Effectiveness of behavioural safety belt interventions. Accident Anal Prev 26:315–323

Joscelyn KB, Bryan TH, Golden-Baum DH (1971) A study of the effects of law enforcement on traffic flow behaviour. National Highway Trafic Safety Administration, U. S. Department of Transportation

Lapham SC, Todd M (2012) Do deterrence and social-control theories predict driving after driving 15 years after a DWI conviction? Accident Anal Prev 45:142–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2011.12.005.Do

Lester S (1999) An introduction to phenomenological research. Retrieved Febr 18(2):1–4. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9450.1984.tb01000.x

Maroney S, Dewar R (1987) Alternatives to enforcement in modifying the speeding behavior of drivers. Transp Res Rec 1111:121–126. 00464603

Mattaini MA (1996) Public issues, human behaviour, and cultural design. In: Mattaini MA, Thyer BA (eds.) Finding solutions to social problems: Behavioural strategies for change. American Psychological Association, pp. 13–40

McDonald H, Berecki-Gisolf J, Stephan K, Newstead S (2020) Traffic offending and deterrence: an examination of recidivism amongst drivers in Victoria, Australia born prior to 1975. PLoS ONE 15:9–12. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239942

Miller T, Blewden M, Zhang JF (2004) Cost savings from a sustained compulsory breath testing and media campaign in New Zealand. Accident Anal Prev 36(5):783–794

Myjoyonline.com (2021) Police MTTD mounts 3000 intelligent surveillance cameras to capture negligent drivers. MyJoyOnline.com. https://www.myjoyonline.com/police-mttd-mounts-3000-intelligent-surveillance-cameras-to-capture-negligent-drivers/

National Road Safety Commission (2017) 2017 road traffic road crashes in Ghana. National Road Safety Commission

Nunn J (2020) The criminal histories of drug drive offenders. Policing 14(2):456–468

Plant KL, McIlroy RC, Stanton NA (2018) Taking a “7 E’s” approach to road safety in the UK and beyond. Ergon Hum Factors 9. https://publications.ergonomics.org.uk/uploads/Taking-a-‘7-E’s’-approach-to-road-safety-in-the-UK-and-beyond-.pdf

Porter BE (2011) Enforcement. In: Porter BE (ed) Handbook of traffic psychology. Academic Press, pp. 441–453

Sandelowski M (1995) Sample size in qualitative research. Res Nurs Health 18:179–183. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.4770180211

Shaaban K (2017) Assessment of drivers’ perceptions of various police enforcement strategies and associated penalties and rewards. J Adv Transp 2017:1–14

Skinner BF (1953) Science and human behaviour. Free Press

Soole DW (2012) The relationship between drivers’ perceptions toward police speed enforcement and self-reported speeding behaviour. Queensland University of Technology

Soole DW, Watson B, Lennon A (2009) The impact of police speed enforcement practices on self-reported speeding: an exploration of the effects of visibility and mobility. In: Australasian road safety research, policing and education conference, November 1–11. http://eprints.qut.edu.au/29382/

Stafford MC, Warr M (1993) A reconceptualisation of general and specific deterrence. J Res Crime Delinquency 30(2):123–135. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022427893030002001

Stradling SG, Martin L, Campbell M (2005) Effects of speed cameras on driver attitude and behaviour. In: Underwood G (ed.) Traffic and transport psychology: theory and application. Elsevier, pp. 513–520

Tankebe J, Boakye KE, Amagnya MA (2020) Traffic violations and cooperative intentions among drivers: the role of corruption and fairness. Polic Soc 30(9):1081–1096. https://doi.org/10.1080/10439463.2019.1636795

Tay R (2005) General and specific deterrent effects of traffic enforcement: do we have to catch offenders to reduce crashes? J Transp Econ Policy 39(2):209–223

Truelove V, Freeman J, Mills L, Kaye S-A, Watson B, Davey J (2021) Does awareness of penalties influence deterrence mechanisms? A study of young drivers’ awareness and perceptions of the punishment applying to illegal phone use while driving. Transp Res Part F 78(2):194–206

Tudor-Owen J (2021) The Importance of “Blue Shirts” in Traffic Policing. Policing 15(1):480–491. https://doi.org/10.1093/police/paz012

Tyler TR (2006) Why people obey the law. In Why people obey the Law. Yale University Press, Tyler

Watson B, Freeman J (2007) Perceptions and experiences of random breath testing in Queensland and the self-reported deterrent impact on drunk driving. Traffic Inj Prev 8(1):11–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/15389580601027360

Wells H (2008) The techno-fix versus the fair cop: procedural (in)justice and automated speed limit enforcement. Br J Criminol 48(6):798–817. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azn058

Wells JK, Preusser D, Williams AF (1992) Enforcing alcohol-impaired driving and seat belt use laws. J Saf Res 23:63–71

World Health Organization (2018) Global status report on road safety 2018. World Health Organization

Zaal D (1994) Traffic law enforcement: a review of the literature, Monash University Accident Research Centre. vol 53

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The study was performed in line with the University of Education, Winneba (UEW) Research Ethics Policy (2018) which “provides an overarching framework regarding ethical conduct and research of UEW involving human and non-human subjects” (p. 1).

Informed consent

The study sought verbal consent from all participants before the interviews. All information obtained was kept strictly confidential and used for the analysis only.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sam, E.F. How effective are police road presence and enforcement in a developing country context?. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 9, 55 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01071-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01071-1