Abstract

A new term, autonomic imbalance (自律神經失調 or AI), which refers to a wide variety of physical and mental symptoms that are medically unexplained, has recently emerged in Taiwan. Many people compared this condition to neurasthenia, a now obsolete diagnosis. Whether neurasthenia and AI are medically the same or merely similar is a debate that is better left to clinicians; however, this article endeavours to explore the significance of the comparability in terms of socio-cultural theory of health. With Deleuze and Guattari’s notion of minor literature as reference, the objectives of this paper are as follows: to address how and why neurasthenia and AI should be treated as ‘minor diagnoses’ and consequently expose the limitations of current clinical medicine; to provide and discuss reasons why AI can be seen as a reincarnated form of neurasthenia; and to further elaborate how this approach may elevate inquiries on the varieties of medically unexplained symptoms to highlight the bodies that suffer without a legitimate name.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A new term, autonomic imbalance (自律神經失調, zilushenjin shitiao or AI), which refers to a wide variety of physical and mental symptoms that are medically unexplained, has recently emerged in Taiwan (Chen 2021; Tu et al. 2021). Although the autonomic nervous system (ANS) has been documented for centuries (Ackerknecht 1974), the popularisation of AI in Taiwan is an insidious and relatively recent process (Chen 2021; Wang 2017). AI was introduced into clinical vocabulary approximately 15 years ago in association with translated self-help publications from Japan. This condition is not a formal diagnosis, because it is not listed in any medical classificatory systems, such as International Classification of Disease (ICD) and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). However, AI has become popular as a new ‘citizen’s illness’ in various TV programmes and books. A famous physician specialising in AI treatment, claimed that AI is an illness of civilisation that is present in approximately 4% of Taiwan’s population (Guo 2012).

AI refers to a dysregulated state of the ANS, which functions independently of one’s own will and consists of sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems that often work antagonistically; this system innervates and coordinates major organs in the human body, including the heart, lungs, blood vessels, bowel, urinary bladder and sexual organs (Gabella 1976). AI clinically manifests in varied forms and combinations, such as palpitation, difficulty in breathing (dyspnoea), irregular bowel movement including constipation and diarrhoea, urine frequency, blurred vision, dizziness, dyspepsia and sexual dysfunction. These symptoms can be transient, short lived, chronic or recalcitrant even with aggressive treatment. No satisfactory medical explanation has been presented for these symptoms, except being classified as ‘functional disturbances’, another confusing terminology. Therefore, AI concurs with the notion of medically unexplained symptoms (MUS) (Chen 2021).

MUS are easily ignored by physicians or attributed to psychiatric conditions, because they are amorphous by definition and, thus, poorly understood (Jutel 2010; Nettleton 2006; Rosendal et al. 2015; Stockl 2007; Ostbye et al. 2020). Different MUS forms have various names, histories and explanatory models (Henningsen et al. 2011; Rief and Broadbent 2007). Naming a disease is generally descriptive and prescriptive (Jutel 2011; Jutel and Nettleton 2011), and labelling MUS constitutes a wide spectrum. Some conditions eventually acquired a name and a tentative pathophysiological explanation, such as chronic fatigue syndrome and fibromyalgia, and left this ill-defined category of MUS (Madden and Sim 2016; Aronowitz 1998; Picariello et al. 2015). For other conditions, their diagnostic status stays undefined in clinical encounters (Chalder and Willis 2017).

According to my research, many interviewees compared AI to neurasthenia, a now obsolete diagnosis. This comparison seems reasonable because both conditions are ill-defined, cover a wide range of physical symptoms, lack satisfactory medical explanations, and therefore, are within the spectrum of MUS. Whether neurasthenia and AI are medically the same or merely similar is a debate that is better left to clinicians; however, what interests me is the significance of the comparability in terms of socio-cultural theory of health. In other words, what theoretical insight may arise from the comparison of neurasthenia and AI that is practically important?

In this regard, hysteria, an old and mysterious illness, is a good demonstration.

Hysteria has long been noted for its multiple manifestations and interpretations. Its dramatic presentations and postulated pathologies have eluded clinicians for centuries (Veith 1965; Scull 2009). In a sense, hysteria is a traditional form of MUS. In addition to the ancient, speculative ‘wondering uterus’ hypothesis, most physicians with anatomical knowledge have viewed this condition as a ‘functional’ disease for centuries (Veith 1965). The famous 19th-century French clinician Jean-Martin Charcot defined hysteria as a neurological condition with a ‘dynamic lesion’, whereas the founder of psychoanalysis, Sigmund Freud, considered it an expression of repressed emotions and mental associations (Micale 1995, 1993; Scull 2009). Knowledge on hysteria paved the foundation of psychoanalysis and the discovery of unconsciousness (Ellenberger 1981). Despite being a prevalent diagnosis in late 19th-century Europe, hysteria gradually ‘disappeared’ in clinical medicine and psychiatry from the turn of the twentieth century (Micale 1995; Taylor 2001).

Its disappearance aroused many speculations. Some scholars claim that hysteria no longer exists because of diagnostic changes (Slavney 1990; Micale 1995) or its sexist connotations (Showalter 1987). The thesis implies that hysteria persists, albeit in different guises. Some academics argue that the general people’s increased ‘psychologising’ capacity has reduced the need and space for somatising their inhibited desires and emotions (Micale 1993; Shorter 1992). Individuals can now ventilate their feelings through words and no longer through the body. As a result, the once popularised dramatic behaviours and vehement emotions of patients with hysteria through Charcot’s (1987[1887]) demonstration at Salpetrière are truly gone.

The history of hysteria exposes the ontological and epistemological uncertainties surrounding MUS, and I would argue that similar issues apply to neurasthenia, AI and probably other forms of MUS. Treating these symptoms as part of this spectrum brings about insights into the implications and limitations of medical diagnosis and understanding. In the following sections, I will trace the history of neurasthenia in Taiwan and its surrounding areas as the background to contextualise my empirical findings on AI.

Neurasthenia in Taiwan and beyond

First raised in 1869 by a Boston physician, George Beard, neurasthenia is characterised by a multiplicity of non-specific symptoms, with fatigue and exhaustion as the most salient (Beard 1869, 1879). ‘More common than any other form of nervous disease’, as Beard (1879) claimed, this diagnosis was prevalent in the US in late 19th-century North America and soon spread to other countries. Although similar symptoms had been noted amongst the sufferers of the ‘English malady’ since the Enlightenment Era, it was neurasthenia, or ‘American nervousness’, which portrayed the sufferers as victims of labour and exhaustion (Porter 2001). The trope of the body as a machine was the major operating metaphor behind the initial idea of neurasthenia (Rabinbach 1992).

In North America, the fervent enthusiasm in this diagnostic label had waned in the early twentieth century. As Shorter (1992) suggested, the once multifarious symptoms clustered under neurasthenia were gradually stripped away by other diagnostic labels such as schizophrenia and anxiety disorders. Eventually, neurasthenia lost its place in psychiatric diagnosis when DSM-III was published in 1980 (Kleinman 1982; Lee and Kleinman 2007), only to reappear in DSM-IV under the glossary of culture-bound syndrome. This condition was also briefly described in the category of undifferentiated somatoform disorder (American Psychiatric Association 1994).

The similarities between hysteria and neurasthenia are so illustrative that the latter is sometimes viewed as the male counterpart of the former (Shorter 1992): both ‘disappeared’ during the first half of the twentieth century, consensus is lacking on how and why they disappeared, and the speculations include increased psychologisation or altered classifications.

In Asian countries, neurasthenia appropriated as a label for those amorphous and changeable somatic symptoms occurred in a colonial context rather than in a rapidly industrialising context. For example, Anderson (2006) addressed the detrimental effects of tropical heat on American colonisers and soldiers in the Philippines that warranted some form of strengthening in the intolerably scorching weather. Japan took up the idea of neurasthenia (Wu 2016) and applied it to the colonial officials in Taiwan who suffered from fatigue, inattention and physical weakness after the Sino-Japanese War in 1895. Their mental and somatic manifestations soon attracted the attention of Japanese physicians, who tended to view these afflicted people as cases of ‘tropical neurasthenia’. As speculated by these physicians, their debility was due to their inability to adapt themselves to the hot and humid environments of Taiwan, which largely differed from the temperate climate of Japan (Wu and Teng 2004).

In China, neurasthenia was soon introduced and applied in various conditions that warranted treatment (Shapiro 2003; Wang 2016). This diagnosis was also initially linked to ‘tropical neurasthenia’. From the late nineteenth century to around the 1930s, tropical neurasthenia was considered a major threat to the health of inhabiting foreigners, including missionaries, who could be incapacitated by nervous breakdown during their stay in the Orient (Wang 2014). In conformity to the then prevalent idea, climate was to blame. Prevention and treatment measures, such as taking a rest regularly and periodically, were forwarded. Psychoanalysis was introduced into China during the 1910s and applied to the understanding of neurasthenia, thereby tremendously changing the previous theories and perspectives. China was read as a metaphorical environ where Occidental people merged themselves in the psychical attraction or the ‘irresistible call of the East’. Tropical neurasthenia transformed from a neurological malady in the face of unfavourable climate to a specific psychological illness for Occidentals who yearn to escape to the Orient (Wang 2014).

Neurasthenia did not only proliferate amongst colonisers and missionaries, but it also spread to Chinese people. For example, renowned historian Gu Jiegang was troubled for decades by neurasthenia, which he attributed to overwork and loss of his loved family members, amongst others (Wang 2013). Although neurasthenia was interpreted as psychological in Republican China, it was viewed in Maoist China as a manifestation of weak will. People with this condition were sent to a hospital where their bodies and minds were reshaped through a series of activities and training, known as the ‘speedy and synthetic therapy’ (Wang 2019). Although the treatment did not last for long, neurasthenia became a major diagnosis in primary psychiatric clinics.

When anthropologist Arthur Kleinman entered China for the sake of research in the 1980s, neurasthenia remained a popular diagnostic label for patients with variegated somatic symptoms (Kleinman 1986). In 1980, he interviewed 100 Hunan patients previously diagnosed with neurasthenia and reclassified 87 of them as cases of major depressive disorder or anxiety disorders. By considering the persistent traumatising effects of political upheavals and turmoil in China in the previous decades, Kleinman reasoned that somatisation, defined as ‘the expression of personal and social distress in an idiom of bodily complaints and medical help seeking’ (Kleinman 1986, p. 51), allowed those unspoken yet collective sufferings to transform onto the body and manifest themselves as pain and other physical symptoms (Kleinman 1986). Although somatisation is also present in Western cultures, it plays an indispensable role in mediating culture and illness in Chinese society and becomes the intersection point for psychiatry and anthropology (Kleinman 1982; Kleinman 1988; Kleinman et al. 1997). In his follow-up study in 1983, he found that the increased attribution of physical pain to psychological causes (i.e. psychologisation) was associated with active help seeking, though the preferred diagnosis was still neurasthenia (Kleinman 1986).

Lee Sing conducted a follow-up for neurasthenia in China in the 1990s and found that the clinical use of neurasthenia had waned (Lee 1994; Lee and Kleinman 2007; Lee 1999). Instead, depression as a diagnostic label was on the rise. He conceived this transformation as ‘a product of interests and strategies that are themselves embedded in a confluence of historical, social, political, and economic forces’. (Lee 1999, p. 349) These forces included the dominance of American psychiatric classification, depoliticisation of human experiences and commercialisation of suffering through antidepressants from global pharmaceutical companies that followed the Open Door Policy of China since the 1980s.

Nevertheless, neurasthenia is not dead. To date, this diagnosis has stayed in the current Chinese Classification of Mental Disorders (the 3rd edition), listed under the category of ‘neurosis’ which includes phobias, anxiety disorders and most closely, somatoform disorders.

The evolution of neurasthenia in Taiwan was less examined. After World War II, Taiwan was ceded by Japan to the Nationalist (Kuomingtang) Government, which retreated to this island soon after it lost mainland China to the Chinese Communist Party. Taiwan has since then separated from China and established liaison with the US (Roy 2003), whose influences expanded into clinical medicine. Neurasthenia continued to be a common term during the 1970s (Kleinman 1981), but its use slowly ebbed in the following decade.

In 1989, psychiatrist Hsien Rin and his colleague Mei-Gum Huang researched the contemporaneous state of neurasthenia diagnosis. Their paper offered a rich account of neurasthenia in late 1980s Taiwan (Rin and Huang 1989). In a survey that covered 70 first-time psychiatric patients, 6 Chinese medicine practitioners, 44 Western medicine practitioners excluding neuropsychiatrists and 35 junior neuropsychiatrists, they found that neurasthenia was used widely amongst the public and Chinese medicine practitioners. Approximately 30% to 40% of junior neuropsychiatrists and non-psychiatrist Western medicine practitioners used this term for communicative purposes. Over half of the participating psychiatric patients reportedly viewed themselves as neurasthenic, but in reality they were clinically diagnosed with psychoses, neuroses and other conditions. By contrast, only 1.5% of all diagnoses for the neurosis category in National Taiwan University Hospital was labelled as neurasthenic neurosis included in DSM-II. In summary, neurasthenia was widely adopted in clinical encounters and patients’ self-diagnosis but rarely used in official records. As Rin and Huang (1989, pp. 223–224) astutely summarised,

In a sense, the vagueness of definition of the term has contributed to its popular appeal both for the public and the medical profession. Not only does the diagnosis of neurasthenia given by Chinese medical men refer to a variety of conditions, it can be and is used interchangeably with psychoneurosis, sometimes depression, and even psychosis, including schizophrenia. The absence of stigma attached to neurasthenia has considerable appeal both to the patient and their families and to the doctors.

The accounts of AI seem similar to this description of neurasthenia: the vagueness of definition, the euphemism for various conditions to avoid social stigma, and the acceptance of this term by Chinese medicine practitioners (Chen 2021). Rin and Huang (1989, p. 224) attributed the broad recognition of neurasthenia to the ‘ability to put together and synthesise varied aspects and phenomena’ of the Chinese culture. However, the idea of ‘Chineseness’ undergirding the neurasthenia diagnosis appears to be outmoded now and does not explain why AI has emerged in the twenty-first century. A new approach to formulating these MUS is needed.

In this article, I will focus on the accounts of clinical practitioners and sufferers who compared AI to neurasthenia and propose a theoretical perspective to conceptualise the relationship of the two conditions. Drawing on Deleuze and Guattari’s notion (1986) of minor literature, this work aims to address how and why neurasthenia and AI should be treated as ‘minor diagnoses’ and consequently expose the limitations of current diagnostic classifications. In the final section, I will elaborate how this approach may help illuminate future research directions on the varieties of MUS.

From minor literature to minor diagnosis

Recent years have witnessed Deleuze and Guattari’s concepts and theories applied to social studies of health, especially in terms of mental health and drug use (Duff 2014; Fox 2011; Malins 2004; McLeod 2017). In general, the idea of assemblages is much more widely recognised in social science literature than the idea of minor literature; both represent Deleuze and Guattari’s efforts to dismantle modern conceptualisations of subjectivity, hierarchy and unity in representation. The concept of assemblages describes various phenomena where different elements and desires multiply and associate with one another. The focus of analysis is directed away from the elements themselves (e.g. ‘points’ and ‘subjects’) towards the associations, movements and configurations of these elements (e.g. ‘rhizomes’, ‘lines of flight’, ‘deterritorialisation’ and ‘body without organs’) (Deleuze and Guattari 1987; Duff 2014). By contrast, the idea of minor literature remains mostly in literary critiques.

Deleuze and Guattari (1986) used the notion of ‘minor literature’ to describe Franz Kafka’s works as opposed to major or mainstream literature. Kafka, a Jew in Prague who wrote in German, presented a particular and difficult position by demonstrating what ‘a minority constructs within a major language’ (1986, p. 16). Minor literature differs from major literature in how content relates to expression. In a major literature, content precedes expression; by contrast, ‘a minor, or revolutionary, literature begins by expressing itself and does not conceptualise until afterward’ (1986, p. 28). Minor literature is characterised by its highly de-territorialised language, the connection of the individual to the political and the collective assemblage of enunciation (1986, p. 18). Nicole et al. (2022) have recently addressed recovery from addiction as a minor practice, a similar concept, where the roles of experts, methods and participants are reconfigured.

In the same vein, I hereby coin the term ‘minor diagnosis’ for my analysis. I argue that minor diagnoses are marked by their tendency to represent an unorthodox category using scientific language, the connection of sufferers’ experiences to the inadequacy of medical understanding and the collective assemblages of amorphous mind–body expressions. The minority of neurasthenia and AI is twofold. First is their deterritorialising use of scientific terms such as neuro and autonomic, because the two diagnoses do not stay within the domain of neurology as we know it today but extend way beyond it. Second, although these labels circulate widely in colloquium, they are never official—they are unlikely to be seen in medical certificates, insurance databases or vital statistics. Moreover, their conditions are so variegated and changeable that they resist rigid frameworks and understandings, thus, calling for a reconceptualisation of MUS. Specifically, when manifested symptomatology does not suffice and the aetiological speculations are no less controversial, minor diagnoses revolutionalise how we make sense of human suffering by reconsidering the politics of nosology that underlies the relationship between mind and body, individual and collective, and those seen and unseen. Similar to minor literature that ‘expresses itself and does not conceptualize until afterward’, minor diagnoses spread and do not consolidate until later.

Psychiatry is occasionally summoned to the rescue in cases of minor diagnoses to offer a tentative explanation for the unclassified or unclassifiable symptoms. However, as medical historian Charles Rosenberg (2006) argued, having an explanation does not always mean that psychiatry ‘knows’ what is happening to the patient (Rosenberg 2006). The disputes over the ‘realities’ of hysteria in history have verified this point.

Methodology

This paper is based on a qualitative research from 2015 to 2019 that focused on the rise, popularisation and definitions of AI. The research was approved by the institutional review board of National Yang-Ming University, Taiwan (YM103110E and YM 105115E). Collected data included archival review and in-depth interviews.

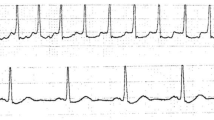

The archival review covered English and Chinese databases, where relevant information was identified using keywords such as autonomic nerves (自律神經), AI (自律神經失調) and neurasthenia (神經衰弱). These databases included PubMed, Web of Science and Airiti Library (a database that collects academic publications written in Chinese) amassing collected newspapers, academic journals and popular magazines. The review constituted the background for interview data analysis. Additionally, interviews were undertaken with 20 respondents, who were mostly medical practitioners (from both Western and Chinese medicine), AI sufferers and academic researchers examining heart rate variability (HRV) in clinical populations. HRV is an indicator of ANS activities that is initially used as a research tool in different medical conditions and disorders and has now been applied in clinical settings for decades (Task Force 1996; Yang and Kuo 2016). HRV measurement is a simple procedure that requires the subject to sit quietly for 5 min while being attached with the HRV equipment, which measures heartbeat changes and mathematically transforms the variations into different parameters. These parameters are correlated with either sympathetic or parasympathetic nervous activities and serve as the basis for different AI typologies (Wang 2017). Irregularities of HRV testing are often colloquially interpreted as signs of AI by clinicians and patients in Taiwan.

Given that the current study is directed on naming and constructing various forms of MUS (AI or neurasthenia) in different times from clinical practitioners’ perspective, the analysis is focused more on their ideas than the sufferers’ views.

Data analysis follows the suggested steps of constructivist grounded theory (Charmaz 2006; Clarke et al. 2017) to clarify the relationship between neurasthenia and AI. Collected data are coded, analysed and compared with current theoretical understandings and relevant formulations.

Findings: identical or similar?

All interviewees agreed that neurasthenia and AI are related, but they disagreed on the manner in which they are related. There are ‘identicalists’, as I call them, who think AI is the same as neurasthenia, simply bearing different names. Nonetheless, most respondents treat neurasthenia and AI as similar but different illnesses. I call these people ‘similarists’. This division may seem hair splitting, because their views converge to a considerable degree. However, what concerns me is the inspirations that these people’s reasoning of the differences (or not) brings to the socio-cultural theorisation of MUS.

Identicalist position: old wine in a new bottle

An identicalist advocate is Dr Chau, my first interviewee and a psychiatrist-researcher who applies HRV tests on patients of various kinds. Dr Chau treats neurasthenia and AI as equivalent and uses them interchangeably in clinical dialogues. In his view, both are lay people’s terms for stress-related disorders. If any, their only difference is the authentication through HRV in the case of AI but not in the case of neurasthenia.

He observed that many patients diagnosed themselves with AI prior to visiting a doctor for confirmation. HRV further offers scientific evidence to corroborate their belief. The scientificity of HRV renders AI as a robust ‘diagnosis’, albeit not a formal one. He would explain to people that the symptoms are caused by ANS dysregulation due to the overuse of ‘brain power’ and excessive stress, the same cause of neurasthenia. As for their response, he said that they will mostly agree.

The idea of AI as a scientifically camouflaged neurasthenia is also entertained by other practitioners. Dr Wu, also a psychiatrist-researcher, admitted that she treated AI as a euphemism for neurasthenia. She reasoned, ‘People who suffer “asthenia” sound like they are almost dying; “imbalance” sounds better’. In addition to the effects of the word choice on patients’ impressions, she granted that authenticating AI by HRV fulfils a wish, which is a pervasive practice in medicine and especially in psychiatry, to ascertain the existence of an illness. However, she candidly explained, ‘I feel AI is a way to somatise psychological problems’. AI (or neurasthenia for that matter) is a façade that covers what is not to be seen. Therefore, psychiatry is necessary for treating these seemingly physical symptoms.

Ms. Chin is a sufferer of AI, now in a stable condition. She considers herself a recovered patient of ‘congenital AI’ and runs a website that promotes self-declared helpful practices to relieve AI symptoms. When asked how she conceived of neurasthenia and AI, Ms. Chin confidently stated that neurasthenia is a concept that ‘psychiatrists used to make it easier for general people to understand [AI].’ According to her, AI is a bona fide disease that has ‘always been there’, and neurasthenia was used instead simply for communicative purposes in clinical encounters. She apparently did not know that AI only recently emerged, whereas neurasthenia had existed for a long time. However, her reasoning echoed the sentiments of the advocates in this group regarding the two conditions:

[Neurasthenia and AI] are actually the same thing. Like I told you, there is a common phenomenon of AI, namely memory decay, right? About cerebral neurasthenia, the first thing that comes to people’s mind is insomnia. The second thing is the insufficiency of “brain power”, like, I could read for two hours non-stop before, but now only for ten minutes. That is cerebral neurasthenia. These are the symptoms they share.

For advocates of this position, AI is nothing but old wine (neurasthenia) in a new bottle (name). Both have non-specific somatic and mental symptoms that do not neatly fit in current diagnostic classifications. Lian and Bondevik (2015) compared medical texts on neurasthenia and encephalomyelitis and found that medical conceptualisations of long-term exhaustion, although bearing different names, are contingent on and infused with coeval cultural values. Wessely (1990, pp. 49–50) expressed a similar viewpoint in terms of the relationship between neurasthenia and myalgic encephalitis, both of which describe a syndrome of excessive fatiguability that ‘can only be understood within their social context’. He reminded that ‘the social processes that govern the creation of such illnesses remain obscure’. Given their marginal nosological statuses, minor diagnoses tend to expose the contesting viewpoints of an illness’ authenticity that may well be black boxed once the illness is officially named. Inspired by Kierans (2020), I argue that both diagnoses act as a ‘worksite’ where the unspecified symptoms and unknown pathologies defy current medical ways of knowing based upon extant mind–body conceptualisations and reflect altered social conditions that underlie these suffering lives, as will be addressed in the next section.

Similarist position: insufficiency versus excess

For similarists, differences between neurasthenia and AI are present in clinical symptomatology and affected populations. Dr Fong is a seasoned cardiologist who applies HRV to study clinical populations, including his patients and people who receive health check-ups in his clinic. He has built up a database by which he established some clinical types on the basis of HRV readings. In his mind, neurasthenia and AI are not specific diseases, but merely symptom clusters or syndromes. Their symptoms overlap to a large degree, but he argues that the two conditions are somehow different. For example, insomnia is a major feature of neurasthenia, whereas AI does not necessarily implicate sleep problems.

Dr Sun, also a psychiatrist-researcher, reflected upon his own clinical experiences. He noted an age-related difference in the acceptance of these two labels. His view in this respect echoed those of Drs Chau and Wu in the first position.

People better accept the idea of AI now, and the younger population is more willing to use this term. Neurasthenia, I feel, points to some kind of passivity. I mean, people rarely come to you and identify themselves with neurasthenia. However, there are a good number of people who are willing to identify themselves with AI when visiting a doctor.

Tu et al. (2021) recently studied Taiwanese patients with ‘autonomic dysregulation’ (another translation of AI) and noted that those people are generally young and frequently experience somatic distress and health anxiety. Their findings confirm Dr Sun’s impressions.

A community psychiatrist, Dr Chen, further added a semantic dimension that distinguishes neurasthenia from AI. In his words, neurasthenia was sometimes called specifically as ‘cerebral’ neurasthenia in Mandarin (腦神經衰弱), where ‘cerebral’ was added to emphasise that the origin is in the brain, a higher source of disease, not the peripheral nerves. For this reason, ‘cerebral’ leads to concrete complaints about the head, such as headache, poor concentration and insomnia.

Therefore, the semantic differences of ‘imbalance’ (失調; shitiau) and ‘asthenia’ (衰弱; shuairuo) demand further explanation (See also Lee 1998; Lee and Wong 1995). The former refers to the loss of harmony (失去調和) or regulation (失去調節), but the word for harmony or regulation (調) also means adjustment (調整) and tuning (微調). Given that the term can also be interpreted as ‘loss of tuning’, people tend to regard AI as something reversible, treatable and improvable. Meanwhile, asthenia (衰弱) consists of two Chinese characters whose meanings are not exactly the same. The first character, 衰 (shuai), means waning power and is often used with words about ageing (e.g. 衰老). The second word, 弱 (ruo), refers to weakness and inferiority (Lee 1998). Another interviewee Dr Wang succinctly summarised the general impression of ‘asthenia’ as ‘diminished capabilities’, as opposed to that of ‘imbalance’ as ‘victims of excessive stress’. The semantic and symptomatic differences imply etiological differences which point to the ontological divergence between neurasthenia and AI.

These differences are similarly noticed in Chinese medicine. Dr Chiang is a Chinese medicine practitioner who also has modern biomedical training. He is keen to the semantic meanings of the two terms and their influence on patients’ self-awareness. Although sleep problems are common to both conditions, he stated, ‘Patients who identify themselves with neurasthenia tend to present symptoms of insufficiency, like fatigue, exhaustion, and poor sleep quality. However, those who say they have AI tend to be more “excited”’. Their treatment, therefore, differs.

Dr Han has practised biomedicine and Chinese medicine for decades and holds the same view about neurasthenia and AI:

They are not entirely the same. Neurasthenia in the past feels like more sympathetic suppression, such as depression, but not like sympathetic excitement. So you may say that autonomic imbalance contains a larger domain than neurasthenia.

Later, he further explained, ‘There are certainly many depressive patients who are categorised as AI in the beginning. However, neurasthenia is not equal to AI, because AI includes cases of sympathetic excitement, which constitute a greater part in clinical encounters’.

Amongst the interviewees, Dr Ju is an extraordinary figure. As an experienced psychiatrist with years of anthropological training in Harvard University, he is familiar with Kleinman’s thesis of neurasthenia and somatisation. He provided a composite picture of neurasthenic patients in Taiwan in the 1980s and offered an explanation for the transition from neurasthenia to AI:

The common cases of neurasthenia were, say, high school students studying to death just to enter college, or public servants or some kind of workers who work day and night for life, for money, and for family. Burning the midnight oil to get into higher education was associated [with neurasthenia] then. In sum, exhaustion of brain power, along with poor material conditions. They thus became very asthenic. In addition, Chinese medicine practitioners promoted the idea of insufficiency, like shu (虛, or emptiness) and kuei (虧, or lack), so they advocated bu (補, supplement or fixing).

There was surely stress in the past, but people tended to think it’s about the insufficiency of the self……However, since the 1990s, the focus has turned to stress, so there has been a tendency to encourage patients to resist stress, to relieve stress, and to resolve stress.

Although the focus is no longer the insufficient self but the excessive stress from outside, the individual is still the one to blame. Dr Ju continued,

Neurasthenia might be due to poverty or inadequate resources that led to the exhaustion of one’s brain power. It was then; it was what people could accept and sympathize with in the 20th century. However, now it is different in the 21st century. Everyone is well nourished and even over-nourished. The responsibility of having AI can be left to no one else but the patient him-/herself. That is, he or she needs to do something to ‘balance it back’.

In this sense, AI can be seen as a reincarnated, post-modernised form of neurasthenia that reflects contemporary life situations. The two conditions are closely related but not the same as suggested by their manifested symptoms and social connotations. Such minor diagnoses lay bare the shifts of dominant social values and local cultural imaginations. In this case, the transition of aetiological emphasis from insufficiency to excess implies the tendency towards the responsibilisation of health that has been associated with neoliberalism (Rose 1996, 1990). The concept was not yet applicable when neurasthenia was popular. However, an increasing number of health and safety issues has been attributed to personal responsibility issues (Pyysiäinen et al. 2017; Gray 2009; Hysing 2021). Although given knowledge or information and endowed with the power to ‘make his/her own choice’, the patient is also held responsible for what he/she chooses (Dent 2006).

Discussion: neurasthenia and AI as minor diagnoses

Upon exposing the diverse viewpoints on the relationship between neurasthenia and AI, the findings lead to an intriguing question: despite so many differences, why do people still think neurasthenia and AI are similar, or even the same, diagnoses? This is where the idea of minor diagnoses sets in, because these diagnoses must have some features in common. First, both are viewed as individuals’ responses to environmental challenges and civilisation stresses, even though their foci of pathogenesis differ. Second, both are perceived as psychosomatic illnesses where personal distresses are expressed through physical channels (i.e. somatisation), but they may present different symptoms. Third, although both are named in scientific terms (neuro- or autonomic), their statuses in official diagnostic frameworks, such as DSM and ICD, are marginal at best or even non-existent. These characteristics put the two diagnoses together as ‘minor’. Their persistent presence attests to the inadequacy of current nosology in addressing the varieties of human suffering.

The idea of minor diagnosis may be applied to the growing list of many other MUS, including long COVID. Although some conditions on the list may have earned an official name in a mainstream classification (e.g. fibromyalgia), many others are expected to remain minor yet frequent in primary care settings (Armstrong 2011; Mik-Meyer and Obling 2012). The idea may alert us to the ‘collective assemblages of enunciation’ they represent.

Conclusion

The exploratory study has highlighted the minor status of these two diagnoses that consequently invokes some reflections.

First, illnesses, along with their names, change over time. A comparison on the basis of symptomatology, aetiology or nosology is insufficient and unconstructive for evaluating MUS in different eras, including neurasthenia and AI. In the spirit of minor diagnosis/literature, the scrutiny must address not only the content (or etiological causes) behind the expression (or physical manifestations) but also the ways by which the expression is interpreted to be representative of certain contents. At this point, minor literature/diagnosis becomes political (Deleuze and Guattari 1986). For example, one thing connecting neurasthenia and AI is their shared mechanism of somatisation (Kleinman 1986). However, compared with the studies on the mechanism’s cultural functions, the reasons why neurasthenia remained as a diagnosis in China and Taiwan in the 1970s and 1980s but was abandoned by Americans are more worthy of exploration. Instead of highlighting the body as the mediator of collective suffering, the nosological politics that has sustained or transformed the cultural mediation must be addressed. Lee (1998) followed up that neurasthenia was replaced by depression gradually in the 1990s after China opened its door to the world a decade earlier. Therefore, a cultural explanation remains incomplete until it is supplemented with a socio-epistemic analysis.

Likewise, the socio-epistemic forces that reify this diagnosis must be considered to understand AI (Taussig 1980). Interviewees such as Dr Ju indicated that this diagnosis avoids potential social stigma attached to mental problems because of its explicitly neurological tone. Conceived as reversible and improvable by oneself, AI escapes the unbearable burden of chronic illnesses and caters to the neoliberal ideals of self-help and self-responsibilisation. HRV further facilitates the use of AI because it adds credibility to the clinical label. The age-related differences in the preference of neurasthenia and AI attest to the social and epistemic configurations that undergird these two minor diagnoses. These characteristics exactly refer to the ‘collective assemblages of enunciation’ across different age populations (Deleuze and Guattari 1986, p. 18).

Second, AI was portrayed previously as a ‘reincarnated, postmodernised form of neurasthenia’, which deserves further elaboration. The idea of reincarnation is borrowed from the title of Taylor’s paper (2001), but the connotations and implications are different herein. Taylor reviewed the records of Queen Square Hospital in London from 1870 to 1947 and found that the disappearance of neurasthenia can be explained chiefly by diagnostic system changes (Taylor 2001). However, in the present article, reincarnation does not mean that neurasthenia has died and transformed into a new diagnostic label, but it explains that minor diagnoses reflecting the amorphous and resistant features of MUS have somehow persisted, similar to minor literature that has thrived on the margins.

Take neurasthenia as an example. It originated in North America, spread widely in the world and remains in use in China. By contrast, AI stemmed from Japan but flourished in Taiwan. Their ‘migration’ is a manifestation of deterritorialisation and reterritorialisation. However, de-/reterritorialisation occurred not only for the diagnoses themselves but also for the body that mediates collective feelings and expressions, regardless of being the substance inhabited by a vulnerable self (as in the case of neurasthenia) or the platform where reactions to stress are imposed onto individuals (as in the case of AI). The body has altered to the extent that it can be treated as a new one. Those exhausted bodies in the 1970s and 1980s have been replaced by anxious bodies in the twenty-first century. Although both neurasthenia and AI are considered MUS with bodily manifestations, the body in these conditions is not a static and stable object but a mobile and metamorphosing medium. This phenomenon explains why AI is cast as a reincarnated form of neurasthenia in a postmodern time, which has diverged from but still linked with modernity. We are now in a new time; we have a new body experiencing new illnesses.

Lastly, the quest on the relationship between neurasthenia and AI as minor diagnoses has led to a new level of inquiries. Instead of splitting and fitting them into mainstream classifications, minor diagnoses compel us to rethink the rhizomic inter-relationships amongst uncertain illnesses that overlap symptomatically and conceptually, such as chronic fatigue syndrome, myalgic encephalitis, fibromyalgia, encephalomyelitis, neurasthenia and now AI (Wessely 1990; Aronowitz 1998; Boulton 2019; Homma et al. 2016; Schafer 2002; Lian and Bondevik 2015). Their shared features include contestations around aetiology and pathogenesis, struggles for legitimacy and identity amongst sufferers, and the questioning of the mind–body dichotomy (Aronowitz 1998; Nettleton 2006; Shattock et al. 2013; Dumit 2006). These diagnoses should be re-evaluated together in a new light. Given that minor literature contains the desires, expressions and ‘lines of escape’ that are hard to dwell in mainstream writings (Deleuze and Guattari 1987, 1986), minor diagnoses accommodate the suffering bodies yearning to be legitimised, understood and comforted in ways that cannot be provided by mainstream medicine (Wainwright et al. 2006). These bodies suffer without a legitimate name. Their presence, persistence and permutations serve as a reminder of their undecided status, where revolutions may arise.

References

American Psychiatric Association. 1994. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, the Fourth Edition (DSM-IV). Arlington: American Psychiatric Association.

Anderson, W. 2006. Colonial Pathologies: American Tropical Medicine, Race, and Hygiene in the Philippines. Durham: Duke University Press.

Armstrong, D. 2011. Diagnosis and Nosology in Primary Care. Social Science & Medicine 73 (6): 801–807.

Aronomwitz, R.A. 1998. Making Sense of Illness: Science, Society and Disease. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Beard, G.M. 1869. Neurasthenia, or Nervous Exhaustion. The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal 3 (13): 217–221.

Beard, G.M. 1879. The Nature and Diagnosis of Neurasthenia. New York: Appleton & Company.

Boulton, T. 2019. Nothing and Everything: Fibromyalgia as a Diagnosis of Exclusion and Inclusion. Qualitative Health Research 29 (6): 809–819.

Chalder, T., and C. Willis. 2017. “Lumping” and “splitting” Medically Unexplained Symptoms: Is There a Role for a Transdiagnostic Approach? Journal of Mental Health 26 (3): 187–191.

Charcot, J.-M. 1987[1887]. Clinical Lectures on Diseases of the Nervous System. London: Routledge.

Charmaz, K. 2006. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Chen, J.-S. 2021. What Is in a Name? Autonomic Imbalance and Medically Unexplained Symptoms in Taiwan. Sociology of Health & Illness 43 (4): 881–894.

Clarke, A.E., C.E. Friese, and R.S. Washburn. 2017. Situational Analysis: Grounded Theory After the Interpretive Turn. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Deleuze, G., and F. Guattari. 1986. Kafka: Toward a Minor Literature. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Deleuze, G., and F. Guattari. 1987. A Thousand Plateaus. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Dent, M. 2006. Patient choice and medicine in health care. Public Management Review 8 (3): 449–462.

Duff, C. 2014. Assemblages of Health: Deleuze’s Empiricism and the Ethology of Life. Dordrecht: Springer.

Dumit, J. 2006. Illnesses You Have to Fight to Get: Facts as Forces in Uncertain, Emergent Illnesses. Social Science & Medicine 62 (3): 577–590.

Ellenberger, H.F. 1981. The Discovery of the Unconscious: The History and Evolution of Dynamic Psychiatry. New York: Basic Books.

Fox, N.J. 2011. The Ill-Health Assemblage: Beyond the Body-with-organs. Health Sociology Review 20 (4): 359–371.

Gabella, B. 1976. Structure of the Autonomic Nervous System. London: Chapman and Hall.

Gray, G.C. 2009. The Responsibilization Strategy of Health and Safety: Neo-liberalism and the Reconfiguration of Individual Responsibility for Risk. The British Journal of Criminology 49 (3): 326–342.

Guo, Y.-H. 2012. If You Do Not Want to Be Sick, Get Your ANS under Control. Taipei: Persimon Publishing Co. (in Chinese).

Henningsen, P., P. Fink, C. Hausteiner-Wiehle, and W. Rief. 2011. Terminology, Classification, and Concepts. In Medically Unexplained Symptoms, Somatisation and Bodily Distress: Developing Better Clinical Services, 1st ed., ed. F. Creed, P. Henningsen, and P. Fink, 43–68. Camrbeidge: Bambridge University Press.

Homma, M., Y. Yamazaki, H. Ishikawa, and T. Kiuchi. 2016. “This Really Explains My Case!”: Biographical Reconstruction of Japanese People with Fibromyalgia Meeting Peers. Health Sociology Review 25 (1): 62–77.

Hysing, E. 2021. Responsibilization: The Case of Road Safety Governance. Regulation & Governance 15 (2): 356–369.

Jutel, A. 2010. Medically Unexplained Symptoms and the Disease Label. Social Theory & Health 8 (3): 229–245.

Jutel, A., and S. Nettleton. 2011. Towards a Sociology of Diagnosis: Reflections and Opportunities Introduction. Social Science & Medicine 73 (6): 793–800.

Jutel, A.G. 2011. Putting a Name to It: Diagnosis in Contemporary Society. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Univeristy Press.

Kierans, C. 2020. Chronic Failures: Kidneys, Regimes of Care, and the Mexican State. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

Kleinman, A. 1981. Patients and Healers in the Context of Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Kleinman, A. 1982. Neurasthenia and Depression: A Study of Somatization and Culture in China. Culture Medicine and Psychiatry 6 (2): 117–190.

Kleinman, A. 1986. Social Origins of Distress and Disease: Depression, Neurasthenia, and Pain in Modern China. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Lee, S. 1998. Estranged Bodies, Simulated Harmony, and Misplaced Cultures: Neurasthenia in Contemporary Chinese Society. Psychosomatic Medicine 60 (4): 448–457.

Lee, S., and A. Kleinman. 2007. Are Somatoform Disorders Changing with Time? The Case of Neurasthenia in China. Psychosomatic Medicine 69 (9): 846–849.

Lee, S., and K.C. Wong. 1995. Rethinking Neurasthenia—The Illness Concepts of Shenjing Shuairuo Among Chinese Undergraduates in Hong Kong. Culture Medicine and Psychiatry 19 (1): 91–111.

Lian, O.S., and H. Bondevik. 2015. Medical Constructions of Long-term Exhaustion, Past and Present. Sociology of Health and Illness 37 (6): 2015.

Madden, S., and J. Sim. 2016. Acquiring a Diagnosis of Fibromyalgia Syndrome: The Sociology of Diagnosis. Social Theory & Health 14 (1): 88–108.

McLeod, K. 2017. Wellbeing Machine: How Health Emerges from the Assemblages of Everyday Life. Durham: Carolina Academic Press.

Micale, M.S. 1993. On the “Disappearance” of Hysteria: A Study in the Clinical Deconstruction of a Diagnosis. Isis 84 (3): 496–526.

Micale, M.S. 1995. Approaching Hysteria: Disease and Its Interpretations. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Mik-Meyer, N., and A.R. Obling. 2012. The Negotiation og the Sick Role: General Practitioners’ Classification of Patients with Medically Unexplained Symptoms. Sociology of Health & Illness 34: 1025–1038.

Malins, P. 2004. Machinic Assemblages: Deleuze, Guattari and an Ethcio-aesthetics of Drug Use. Janus Head 7 (1): 84–104.

Nettleton, S. 2006. “I Just Want Permission To Be Ill”: Towards a Sociology of Medically Unexplained Symptoms. Social Science & Medicine 62 (5): 1167–1178.

Nicole, V., L. Theodoropoulou, and M. Manchot. 2022. Recovery as a minor practice. International Journal of Drug Policy. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2022.103618.

Ostbye, S.V., M.F. Kvamme, C.E.A. Wang, H. Haavind, T. Waage, and M.B. Risor. 2020. “Not a Film About My Slackness”: Making Sense of Medically Unexplained Illness in Youth Using Collaborative Visual Methods. Health: an Interdisciplinary Journal for the Social Study of Health, Illness and Medicine 24 (1): 38–58.

Picariello, F., S. Ali, R. Moss-Morros, and T. Chalder. 2015. The Most Popular Terms for Medically Unexplained Symptoms: The Views of CFS Patients. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 78 (5): 420–426.

Porter, R. 2001. Nervousness, Eithteenth and Ninteenth Centruy Style: From Luxury to Labor. In Cultures of Neurasthenia: From Beard to the First World War, ed. M. Gijswijt-Hofstra and R. Porter, 31–50. New York: Editions Rodopi B.V.

Pyysiäinen, J., D. Halpin, and A. Guifoyle. 2017. Neoliberal Governance and ‘Responsibilization’ of Agents: Reassessing the Mechanisms of Responsibility-Shift in Neoliberal Discursive Environments. Distinktion: Journal of Social Theory 18 (2): 215–235.

Rabinbach, A. 1992. The Human Motor: Energy, Fatigue, and the Origins of Modernity. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Rief, W., and E. Broadbent. 2007. Explaining Medically Unexplained Symptoms-Models and Mechanisms. Clinical Psychology Review 27 (7): 821–841.

Rin, H., and M.G. Huang. 1989. Neurasthenia as Nosological Dilemma. Culture Medicine and Psychiatry 13 (2): 215–226.

Rose, N. 1990. Governing the Soul: The Shaping of the Private Self. London: Routledge.

Rose, N. 1996. Governing “Advanced” Liberal Democracies. In Foucault and Political Reason, ed. T. Barry, T. Osborne, and N. Rose, 37–64. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Rosenberg, C. 2006. Contested Boundaries: Psychiatry, Disease, and Diagnosis. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine 49 (3): 407–424.

Rosendal, M., A.H. Carlsen, M.T. Rask, and G. Moth. 2015. Symptoms as the Main Problem in Primary Care: A Cross-Sectional Study of Frequency and Characteristics. Scandinavian Journal of Primary Health Care 33 (2): 91–99.

Roy, D. 2003. Taiwan: A Political History. Cornell: Cornell University Press.

Schafer, M.L. 2002. On the History of the Concept Neurasthenia and Its Modem Variants Chronic Fatigue-Syndrome, Fibromyalgia and Multiple Chemical Sensitivities. Fortschritte Der Neurologie Psychiatrie 70 (11): 570–582.

Scull, A.T. 2009. Hysteria: The Biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Shapiro, H. 2003. Chinese and Western Medicine. In Medicine across Cultures: History and Practice of Medicine in Non-Western Cultures, ed. Selin, H, 351–372. New York: Kluwer.

Shattock, L., H. Williamson, K. Caldwell, K. Anderson, and S. Peters. 2013. “They’ve Just Got Symptoms Without Science”: Medical Trainees’ Acquisition of Negative Attitudes Towards Patients with Medically Unexplained Symptoms. Patient Education and Counseling 91 (2): 249–254.

Shorter, E. 1992. From Paralysis to Fatigue: A History of Psychosomatic Illness in the Modern Era. New York: The Free Press.

Showalter, E. 1987. The Female Malady: Women, Madness and English Culture, 1830–1980. London: Time Warner Books UK.

Slavney, P.R. 1990. Perspectives on “Hysteria.” Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Stockl, A. 2007. Complex Syndromes, Ambivalent Diagnosis, and Existential Uncertainty: The Case of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE). Social Science & Medicine 65 (7): 1549–1559.

Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology. 1996. Heart Rate Variability - Standards of Measurement, Physiological Interpretation, and Clinical Use. European Heart Journal 17: 354–381.

Taussig, M.T. 1980. Reification and the consciousness of the patient. Social Science & Medicine, Medical Anthropology 14b (1): 3–13.

Tyalor, R.E. 2001. Death of Neurasthenia and its Psychological Reincarnation - A Study of Neurasthenia at the National Hospital for the Relief and Cure of the Paralysed and Epileptic, Queen Square, London, 1870–1932. British Journal of Psychiatry 179: 550–557.

Tu, C.-Y., W.-S. Liu, Y.-F. Chen, and W.-L. Huang. 2021. Patients who Complain of Autonbomic Dysregulation: A Cross-Sectional Study of Patients with Somatic Symptom Disorder. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1177/00207640211025549.

Veith, I. 1965. Hysteria : The History of a Disease. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Wainwright, D., M. Calnan, C. O’Neil, A. Winterbottom, and C. Watkins. 2006. When Pain in the Arm is “all in the head”: The Management of Medically Unexplained Suffering in Primary Care. Health Risk & Society 8 (1): 71–88.

Wang, W.-J. 2013. Gu Jiegang and the Management of Neurasthenia in Republican China. In The 4th International Sinology Conference Proceedings: Health and Medicine, 65–99. Taipei, Taiwan: Academia Sinica (in Chinese)

Wang, W.-J. 2014. Tropical Neurasthenia or Oriental Nerves? White Breakdowns in China. In Psychiatry and Chinese History, ed. H. Chiang, 111–128. London: Pickering & Chatto.

Wang, W.-J. 2019. Neurasthenia, Psy Sciences and the “Great Leap” in Maoist China. History of Psychiatry 30 (4): 443–456.

Wang, W.J. 2016. Neurasthenia and the Rise of Psy Disciplines in Republican China. East Asian Science Technology and Society: An International Journal 10 (2): 141–160.

Wessely, S. 1990. Old Wine in New Bottles: Neurasthenia and “ME.” Psychological Medicine 20 (1): 35–53.

Wu, Y.-C., and H.-W. Tend. 2004. Tropics, Neurasthenia, and Japanese Colonizers: The Psychiatric Discourses in Late Colonial Taiwan. Taiwan: A Radical Quarterly in Social Studies 54: 61–103 (in Chinese).

Wu, Y.-C. 2016. A Disorder of Qi: Breathing Exercise as a Cure for Neurasthenia in Japan, 1900–1945. Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 71 (3): 322–344.

Yang, C.C.H., and T.B. Kuo, eds. 2016. Studies on Heart Rate Variability: From Health Maintenance to Disease Diagnostics. Taipei: Hochi Publishing Co. (in Chinese).

Acknowledgements

The study was sponsored by the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (MOST 106-2410-H-010-006-MY2). A preliminary draft was presented in the 2018 Annual Meeting of the Society for Social Studies of Science in Sydney and in the 2019 Annual Meeting of Taiwanese Sociological Association in Taipei. I thank all the commentators for their invaluable input.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, Js. Neurasthenia and autonomic imbalance as minor diagnoses: comparison, concept and implications. Soc Theory Health 21, 337–353 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41285-022-00184-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41285-022-00184-6