Abstract

The excess mortality burden due to violent fatal injuries is an urgent public health issue for adolescents and young adults, especially those from racial and ethnic minority populations. We examined the research portfolio of the United States National Institutes of Health (NIH) related to violent fatal injuries between 2009 and 2019 to focus on adolescents and young adults from NIH-designated populations experiencing health disparities and to identify trends and research gaps. We analyzed funded projects by populations covered, geographic location of the study population, type of research (etiology, intervention, methodology), type of determinants, and publications generated. In 10 years, NIH funded 17 grants that produced 90 publications. Researchers used socioecological frameworks most to study violent crime, except in rural locations. Research gaps include the direct impact of violent crime among those victimized and health care (the least studied determinant) and premature mortality disparities caused by hate crimes.

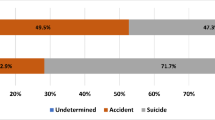

Reproduced from Alvidedrez et. al. (2019) [13]

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

Not applicable.

References

U.S. Department of Justice—Federal Bureau of Investigation. Crime in the United States, 2019. 2020.

Petrosky E, et al. Surveillance for violent deaths—national violent death reporting system, 34 states, Four California Counties, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico, 2017. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2020;69(8):1.

Centers for Disease Control—CDC. WISQARS™—web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System. 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html.

Heron M. Deaths: leading causes for 2017. National Vital Statistics Reports; vol 68, no 6. 2019. National Center for Health Statistics Hyattsville.

Paglino E, et al. Monthly excess mortality across counties in the United States during the Covid-19 pandemic, March 2020 to February 2022. medRxiv 2022.

Rostron A. The Dickey amendment on federal funding for research on gun violence: a legal dissection. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(7):865–7.

Rubin R. Tale of 2 agencies: CDC avoids gun violence research but NIH funds it. JAMA. 2016;315(16):1689–92.

Galea S, Vaughan RD. Learning from the evolving conversation on firearms: a public health of consequence, July 2018. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(7):856–7.

Department of Human Health and Services. A nation free of disparities in health and health care 2011, HHS Action Plan to Reduce Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities Washignton, DC.

Healthy People 2030. Violence prevention. 2020.

National Institutes of Health. NIH-wide strategic plan—2016–2020. 2020.

National Institutes of Health. RePORTER. 2023. https://reporter.nih.gov. Accessed 2022

Alvidrez J, et al. The national institute on minority health and health disparities research framework. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(S1):S16–20.

National Institutes of Health. iSearch: portfolio tool for curation. 2023. https://dpcpsi.nih.gov/sites/default/files/PortfolioTool_one_pager%2004172018.pdf.

Rosenfeld, R., Documenting and explaining the 2015 Homocide rise: research directions. Washington, DC: U.S.D.o. Justice, Editor; 2016

Pyrooz DC, et al. Was there a Ferguson Effect on crime rates in large US cities? J Crim Just. 2016;46:1–8.

Gross N, Mann M. Is there a “Ferguson Effect?” Google searches, concern about police violence, and crime in US cities, 2014–2016. Socius. 2017;3:2378023117703122.

Nix J, Pickett JT. Third-person perceptions, hostile media effects, and policing: developing a theoretical framework for assessing the Ferguson effect. J Crim Just. 2017;51:24–33.

Davey M, Smith M. Murder rates rising sharply in many US cities. The New York Times. 2015;1.

Jones CM, et al. Vital signs: demographic and substance use trends among heroin users—United States, 2002–2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(26):719.

Stoddard SA, et al. The relationship between cumulative risk and promotive factors and violent behavior among urban adolescents. Am J Community Psychol. 2013;51(1–2):57–65.

HDPulse: An ecosystem of minority health and health disparities resource. National Institute on Minority Healthy and Health Disparities. https://hdpulse.nimhd.nih.gov/. Accessed 2 May 2022

Rosenfeld R. Documenting and explaining the 2015 homicide rise: research directions. Washington: National Institute of Justice; 2016.

Hartinger-Saunders RM, et al. Neighborhood crime and perception of safety as predictors of victimization and offending among youth: a call for macro-level prevention and intervention models. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2012;34(9):1966–73.

Margolin G, et al. Violence exposure in multiple interpersonal domains: cumulative and differential effects. J Adolesc Health. 2010;47(2):198–205.

Brown BB, et al. Physical activity mediates the relationship between perceived crime safety and obesity. Prev Med. 2014;66:140–4.

Meyer OL, Castro-Schilo L, Aguilar-Gaxiola S. Determinants of mental health and self-rated health: a model of socioeconomic status, neighborhood safety, and physical activity. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(9):1734–41.

Jones-Webb R, Wall M. Neighborhood racial/ethnic concentration, social disadvantage, and homicide risk: an ecological analysis of 10 US cities. J Urban Health. 2008;85(5):662–76.

Quinsey VL, et al. Violent offenders: appraising and managing risk. Washington: American Psychological Association; 2006.

Raine A, Brennan P, Mednick SA. Birth complications combined with early maternal rejection at age 1 year predispose to violent crime at age 18 years. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51(12):984–8.

Boccellari A, et al. Characteristics and psychosocial needs of victims of violent crime identified at a public-sector hospital: data from a large clinical trial. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2007;29(3):236–43.

Pickett KE, Pearl M. Multilevel analyses of neighbourhood socioeconomic context and health outcomes: a critical review. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2001;55(2):111–22.

Macintyre S, Ellaway A, Cummins S. Place effects on health: how can we conceptualise, operationalise and measure them? Soc Sci Med. 2002;55(1):125–39.

Diez-Roux AV. Bringing context back into epidemiology: variables and fallacies in multilevel analysis. Am J Public Health. 1998;88(2):216–22.

Diez-Roux AV, et al. Neighborhood environments and coronary heart disease: a multilevel analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;185(11):1187–202.

Perry B. In the name of hate: understanding hate crimes. Milton Park: Routledge; 2002.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Roldós, MI., Farhat, T. & Gómez, M.M. Disparities in violent fatal injury among racial and ethnic minorities, 2009–2019: a portfolio analysis of United States—National Institutes of Health. J Public Health Pol 44, 386–399 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41271-023-00418-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41271-023-00418-5