Abstract

The literature on the benefits and costs of financial globalization for developing countries has exploded in recent years, but along many disparate channels with a variety of apparently conflicting results. There is still little robust evidence of the growth benefits of broad capital account liberalization, but a number of recent papers in the finance literature report that equity market liberalizations do significantly boost growth. Similarly, evidence based on microeconomic (firm- or industry-level) data shows some benefits of financial integration and the distortionary effects of capital controls, but the macroeconomic evidence remains inconclusive. At the same time, some studies argue that financial globalization enhances macroeconomic stability in developing countries, but others argue the opposite. This paper attempts to provide a unified conceptual framework for organizing this vast and growing literature, particularly emphasizing recent approaches to measuring the catalytic and indirect benefits to financial globalization. Indeed, it argues that the indirect effects of financial globalization on financial sector development, institutions, governance, and macroeconomic stability are likely to be far more important than any direct impact via capital accumulation or portfolio diversification. This perspective explains the failure of research based on cross-country growth regressions to find the expected positive effects of financial globalization and points to newer approaches that are potentially more useful and convincing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The working paper version of this paper provides a comprehensive list of references (see Kose and others, 2006). In this paper, we limit ourselves to mentioning some key papers and do not aim to be exhaustive in our citations.

Eichengreen (2001), who focuses on the relationship between growth and measure of restrictions on capital account transactions, argues that the evidence is quite mixed. A subsequent survey by us on the broader dimensions of financial globalization deepens the puzzle (Prasad and others, 2003). We conclude that the vast empirical literature provides little robust evidence of a causal relationship between financial integration and growth. Moreover, we find that, among developing countries, the volatility of consumption growth relative to income growth appears to be positively associated with financial integration, the opposite of what canonical theoretical models would predict.

We emphasize up front that our analysis focuses largely on private capital flows and does not encompass the effects of official flows, including foreign aid, and other flows such as remittances (which should, strictly speaking, appear in the current account of the balance of payments).

Indeed, from 2004 to 2006, developing countries and emerging markets collectively averaged a large current account surplus, rather than a deficit. Lucas himself offered a new growth model based on increasing returns to human capital to explain what was then a low volume of net flows to developing countries, though recent work has tended to focus more on the financial channel emphasized contemporaneously by Gertler and Rogoff (1990). Mendoza, Quadrini, and Rios-Rull (2007) and Alfaro, Kalemli-Ozcan, and Volosovych (2007) argue that institutional failures more generally may lead to capital flow reversals. Reinhart and Rogoff (2004) suggest that recurrent defaults and financial crises in developing countries may depress investment there. Gordon and Bovenberg (1996) focus on the role played by information asymmetries.

Henry (2007) argues that, even in the context of the basic neoclassical model, the financing channel should imply only a temporary, rather than permanent, pickup in growth from financial integration. It is not clear, however, how important this nuance is likely to be empirically in studies that look at growth experiences over periods of just two to three decades.

Among developed countries and across regions within developed countries, better risk sharing is associated with greater specialization (Obstfeld, 1994; Acemoglu and Zilibotti, 1997; and Kalemli-Ozcan, Sorensen, and Yosha, 2003).

See Kose, Prasad, and Terrones (2004) for a more detailed exposition.

In particular, the welfare gains depend on the volatility of output shocks, the rate of relative risk aversion, the risk-adjusted growth rate, and the risk-free interest rate in these models (see the discussion in Obstfeld and Rogoff, 2004, Chapter 5; Lewis, 1999; and van Wincoop, 1999). Lucas's (1987) claim that macroeconomic stabilization policies that reduce consumption volatility can have only minimal welfare benefits continues to be influential in the literature (see Barlevy, 2004).

Share measures have been created by Grilli and Milesi-Ferretti (1995), Rodrik (1998), and Klein and Olivei (2006). Finer measures of openness based on the AREAER have been developed by Quinn (1997, 2003), Miniane (2004), Chinn and Ito (2006), Mody and Murshid (2005), and Edwards (2005). Edison and Warnock (2003) construct measures of capital account restrictions related to just equity flows. Bekaert and Harvey (2000) and Henry (2000a) compile dates of equity market liberalizations for developing countries. We briefly discuss some of these narrower measures in more detail later.

Other measures of integration include saving-investment correlations and, related to the price-based approach discussed above, various interest parity conditions (see Frankel, 1992; and Edison and others, 2002). However, these measures are also difficult to operationalize and interpret for an extended period of time and for a large group of countries.

These authors substantially extend their External Wealth of Nations database (Lane and Milesi-Ferretti, 2001) using a revised methodology and a larger set of sources. Although their benchmark series are based on the official estimates from the International Investment Position, they compute the stock positions for earlier years using data on capital flows and account for capital gains and losses.

FDI refers to direct investment in a domestic company, giving the foreign investor an ownership share. Portfolio equity inflows refer to foreign investors’ purchases of domestically issued equity in a company. Debt inflows include foreign investors’ purchases of debt issued by corporates or the government, and also foreign borrowing undertaken by domestic banks.

An earlier wave of financial globalization (1880–1914) has been analyzed by Bordo, Taylor, and Williamson (2003), Obstfeld and Taylor (2004), and Mauro, Sussman, and Yafeh (2006).

The sample of countries used in our analysis is listed in the Data Appendix.

Certain measures of de jure integration do track the de facto measures better. For instance, the Edison-Warnock measure of restrictions on equity inflows does change more in line with de facto integration in emerging markets, but this measure is available for only a limited number of countries and for a short time interval. Moreover, equity inflows constitute only a small portion of total inflows.

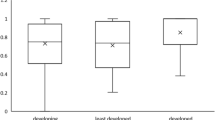

Some countries underwent financial integration during this period, especially in the latter half of the 1990s. Therefore any result based on the average growth over this period should be interpreted with caution. The list of countries in our sample is listed in the Data Appendix.

We excluded from these plots a few countries that were outliers, mostly those with very high levels of financial openness relative to GDP (see the Data Appendix). Using the full sample of countries made little difference to the correlations shown here. We do not systematically examine the effects of outliers as these plots are meant to be descriptive and do not constitute formal empirical evidence.

See Kraay (1998), O’Donnell (2001), and Edison and others (2002).

On the last point, see Edwards (2001) and Edison and others (2004). Quinn (1997) and Arteta, Eichengreen, and Wyplosz (2003) report uniform results for all groups of countries.

These authors use a binary capital account openness indicator based on the IMF's AREAER. Whether this relationship holds up with de facto measures remains to be seen.

On the output costs of banking crises, see Hutchinson and Noy (2005) and Bonfiglioli and Mendicino (2004).

The evidence cited on this point by some prominent critics of globalization in fact turns out to be about how domestic financial sector liberalization, rather than financial integration, has in some cases precipitated financial crises (see footnote 5 in Stiglitz, 2004).

A number of recent theoretical papers have attempted to explain the hump-shaped relationship between financial integration and the relative volatility of consumption growth. Levchenko (2005) and Leblebicioglu (2006) consider dynamic general equilibrium models where only some agents have access to international financial markets. In both models, financial integration leads to an increase in the volatility of aggregate consumption because agents with access to international financial markets stop participating in risk-sharing arrangements with those who lack such access. Bekaert, Harvey, and Lundblad (2005) find that consumption volatility declines following equity market liberalizations. Kose, Prasad, and Terrones (forthcoming) show that emerging market economies, which have experienced large increases in cross-border capital flows, have seen little change in their ability to share risk during the globalization period.

Recent surveys of this literature include Lipsey (2004) and Moran, Graham, and Blomström (2005).

Along similar lines, it should be noted that Morocco and Venezuela were relatively closed to trade during the periods covered by the country-specific panel data sets used in the influential studies by Haddad and Harrison (1993) and Aitken and Harrison (1999), respectively, both of which concluded that FDI has minimal growth benefits (see Moran, Graham, and Blomström, 2005).

Blonigen and Wang (2005) discuss the pooling issue but Aykut and Sayek (2005) analyze the effects of sectoral composition of FDI inflows. The importance of the three initial conditions is shown by Borensztein, De Gregorio, and Lee (1998), Hermes and Lensink (2003), Alfaro and others (2006), and Balasubramanyam, Salisu, and Sapsford (1996), respectively. On the last point, also see Melitz (2005).

Lipsey and Sjöholm (2005) provide a survey of the evidence on FDI spillovers. Also see Görg and Greenaway (2004). For more evidence on FDI spillovers through backward linkages, see López-Córdova (2003), Alfaro and Rodríguez-Clare (2004), and Blalock and Gertler (2005).

Also see Li (2003). Equity market liberalizations are defined as events that make shares of common stock of local firms available to foreign investors. Commonly used dates, drawn from Henry (2000a) and Bekaert and Harvey (2000), include official liberalization dates and dates of “first sign” of liberalization based on events such as the launching of a country fund or American Depository Receipt (ADR) announcement. ADRs are securities that are traded in the United States but represent underlying stocks listed in a foreign country.

Recent research also provides some cross-country evidence about the empirical relevance of various channels linking equity market liberalization to economic growth. There is evidence, consistent with the predictions of international asset pricing models, that stock market liberalizations reduce the cost of capital and boost investment growth. For evidence on the first point, see Stulz (1999a, 1999b), Bekaert and Harvey (2000), Henry (2000a), and Kim and Singal (2000). On the latter, see Henry (2000b) and Alfaro and Hammel (2006).

See Diamond and Rajan (2001) and Jeanne (2003), respectively, on these two points about the potential benefits of debt flows. For a survey of the empirical literature on the risks associated with short-term debt, see Berg, Borenzstein, and Pattillo (2004).

Johnson and Mitton (2002) argue that capital controls reduced market discipline among Malaysian firms and fostered cronyism. Desai, Foley, and Hines (2004) use firm-level data to argue that the cost of capital is higher for multinationals when capital controls are in place. Based on the cross-country investment patterns of multinationals, they conclude that the level of FDI inflows into a country is adversely affected by capital controls. Forbes (2005b) concurs that the costs of capital controls include not just efficiency losses and lower market discipline but also reduced inflows. Magud and Reinhart (2007) discuss the difficulty of using macro data to measure the costs of capital controls.

A number of papers have explicitly taken the tack that the costs of financial globalization—including crises—are in the nature of growing pains that will recede once globalizing economies achieve fuller integration (Krugman, 2002; Martinez, Tornell, and Westermann, 2004).

Recent literature has emphasized the importance of TFP growth as the main driver of long-term GDP growth (see, for example, Hall and Jones, 1999; Jones and Olken, 2008; Gourinchas and Jeanne, 2006). Edwards (2001), Bonfiglioli (2006), and Kose, Prasad, and Terrones (2008) have assembled some preliminary evidence suggesting that financial integration raises TFP growth. Kose, Prasad, and Taylor (forthcoming) provide a detailed analysis of various threshold factors that help promote the growth benefits of financial integration.

As with Figure 3a, we excluded a few countries that were outliers. Inclusion of all the countries in our sample strengthened the unconditional cross-sectional correlations shown here.

In a cross-county regression framework, Chinn and Ito (2006), however, identify one possible caveat. Financial openness contributes to equity market development only once at least a moderate level of legal and institutional development has been attained (a hurdle cleared by most emerging markets); less developed countries do not necessarily gain this benefit.

Another threshold effect, on which the literature is still rather limited, is related to human capital. Borensztein, De Gregorio, and Lee (1998) and Blonigen and Wang (2005) find that countries that have more human capital get larger growth benefits from FDI.

Austria and Hungary, for example, were able to avoid crises after they liberalized their capital accounts since they had relatively stable macroeconomic policies. Mexico and Turkey ran into difficulties in the mid-1990s after liberalizing their capital accounts because they had tightly managed exchange rates for a prolonged period, along with uncertain policy settings and growing imbalances.

See Husain, Mody, and Rogoff (2004) and Aghion and others (2006). For a discussion of how fixed exchange rate regimes and open capital accounts can together spell disaster, see Obstfeld and Rogoff (1995) and Wyplosz (2004).

Calvo and Talvi (2005) claim that this is why the collapse of capital flows to Argentina and Chile in the 1990s had a smaller impact on Chile. Kose, Meredith, and Towe (2005) argue that trade integration has made the Mexican economy more resilient to shocks and contributed to its faster recovery from the 1994–95 peso crisis than from the 1982 debt crisis.

For presentational reasons, in Figures 3a and 6 we excluded the following countries that were outliers: United Kingdom (GBR), Netherlands (NLD), Belgium (BEL), Singapore (SGP), Switzerland (CHE), Ireland (IRL), Zambia (ZMB), and China (CHN). Inclusion of outliers did not change our qualitative findings.

References

Acemoglu, Daron, and Fabrizio Zilibotti, 1997, “Was Prometheus Unbound by Chance? Risk, Diversification, and Growth,” Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 105, No. 4, pp. 709–751.

Aghion, Philippe, and Abhijit Banerjee, 2005, Volatility and Growth: Clarendon Lectures in Economics (New York, Oxford University Press).

Aghion, Philippe, Philippe Bacchetta, Romain Ranciere, and Kenneth Rogoff, 2006, “Exchange Rate Volatility and Productivity Growth: The Role of Financial Development,” NBER Working Paper No. 12117 (Cambridge, Massachusetts, National Bureau of Economic Research).

Aitken, Brian J., and Ann E. Harrison, 1999, “Do Domestic Firms Benefit from Direct Foreign Investment? Evidence from Venezuela,” American Economic Review, Vol. 89, No. 3, pp. 605–618.

Alesina, Alberto, Vittorio Grilli, and Gian Maria Milesi-Ferretti, 1994, “The Political Economy of Capital Controls,” in Capital Mobility: The Impact on Consumption, Investment, and Growth, ed. by Leonardo Leiderman and Assaf Razin (Cambridge, United Kingdom, Cambridge University Press for the Centre for Economic Policy Research).

Alfaro, Laura, and Andrés Rodríguez-Clare, 2004, “Multinationals and Linkages: An Empirical Investigation,” Economía, Vol. 4, No. 2, pp. 113–170.

Alfaro, Laura, and Eliza Hammel, 2006, “Capital Flows and Capital Goods,” (unpublished; Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Business School).

Alfaro, Laura, Areendam Chanda, Sebnem Kalemli-Ozcan, and Selin Sayek, 2004, “FDI and Economic Growth: The Role of Local Financial Markets,” Journal of International Economics, Vol. 64, No. 1, pp. 89–112.

Alfaro, Laura, Areendam Chanda, Sebnem Kalemli-Ozcan, and Selin Sayek, 2006, “How Does Foreign Direct Investment Promote Economic Growth? Financial Markets as a Catalyst for Linkages,” (unpublished; Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Business School).

Alfaro, Laura, Sebnem Kalemli-Ozcan, and Vadym Volosovych, 2007, “Capital Flows in a Globalized World: The Role of Policies and Institutions,” in Capital Controls and Capital Flows in Emerging Economies: Policies, Practices, and Consequences, ed. by Sebastian Edwards (Chicago, University of Chicago Press), pp. 19–68.

Arteta, Carlos, Barry Eichengreen, and Charles Wyplosz, 2003, “When Does Capital Account Liberalization Help More than It Hurts?” in Economic Policy in the International Economy: Essays in Honor of Assaf Razin, ed. by Elhanan Helpman and Efraim Sadka (Cambridge, United Kingdom, Cambridge University Press).

Aykut, Dilek, and Selin Sayek, 2005, “The Role of the Sectoral Composition of Foreign Direct Investment on Growth,” (unpublished; Washington, World Bank).

Bailliu, Jeannine, 2000, “Private Capital Flows, Financial Development, and Economic Growth in Developing Countries,” Bank of Canada Working Paper 2000–15.

Balasubramanyam, V.N., Mohammed Salisu, and David Sapsford, 1996, “Foreign Direct Investment and Growth in EP and IS Countries,” Economic Journal, Vol. 106, No. 434, pp. 92–105.

Barlevy, Gadi, 2004, “The Cost of Business Cycles under Endogenous Growth,” American Economic Review, Vol. 94, No. 4, pp. 964–990.

Bartolini, Leonardo, and Allan Drazen, 1997, “Capital-Account Liberalization as a Signal,” American Economic Review, Vol. 87, No. 1, pp. 138–154.

Beck, Thorsten, and Ed Al-Hussainy, 2006, Financial Structure Dataset (Washington, World Bank).

Bekaert, Geert, and Campbell R. Harvey, 2000, “Foreign Speculators and Emerging Equity Markets,” Journal of Finance, Vol. 55, No. 2, pp. 565–613.

Bekaert, Geert, Campbell R. Harvey, and Christian Lundblad, 2001, “Emerging Equity Markets and Economic Development,” Journal of Development Economics, Vol. 66, No. 2, pp. 465–504.

Bekaert,Geert, Campbell R. Harvey, and Christian Lundblad, 2005, “Does Financial Liberalization Spur Growth?” Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 77, No. 1, pp. 3–55.

Berg, Andrew, Eduardo Borensztein, and Catherine Pattillo, 2004, “Assessing Early Warning Systems: How Have They Worked in Practice?” IMF Working Paper 04/52 (Washington, International Monetary Fund).

Bhagwati, Jagdish, 1998, “The Capital Myth. The Difference between Trade in Widgets and Dollars,” Foreign Affairs, Vol. 7, No. 3, pp. 7–12.

Blalock Garrick, and Paul J. Gertler, 2005, “Foreign Direct Investment and Externalities: The Case for Public Intervention,” in Does Foreign Investment Promote Development? ed. by Theodore H. Moran, Edward M. Graham, and Magnus Blomström (Washington, Institute for International Economics).

Blonigen, Bruce A., and Miao Grace Wang, 2005, “Inappropriate Pooling of Wealthy and Poor Countries in Empirical FDI Studies,” in Does Foreign Investment Promote Development? ed. by Theodore H. Moran, Edward M. Graham, and Magnus Blomström (Washington, Institute for International Economics).

Bonfiglioli, Alessandra, 2006, “Financial Integration, Productivity and Capital Accumulation,” (unpublished; Barcelona, Universitat Pompeu Fabra).

Bonfiglioli, Alessandra, and Caterina Mendicino, 2004, “Financial Liberalization, Banking Crises, and Growth: Assessing the Links,” Scandinavian Working Paper in Economics No. 567 (Stockholm School of Economics).

Bordo, Michael, Alan M. Taylor, and Jeffrey G. Williamson, 2003, Globalization in Historical Perspective (Chicago, University of Chicago Press for the National Bureau of Economic Research).

Borensztein, Eduardo, José De Gregorio, and Jong-Wha Lee, 1998, “How Does Foreign Direct Investment Affect Growth?” Journal of International Economics, Vol. 45, No. 1, pp. 115–135.

Bosworth, Barry P., and Susan M. Collins, 1999, “Capital Flows to Developing Economies: Implications for Saving and Investment,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Vol. 1, pp. 143–169.

Buch, Claudia M., Jörg Döpke, and Christian Pierdzioch, 2005, “Financial Openness and Business Cycle Volatility,” Journal of International Money and Finance Vol. 24, No. 5, pp. 744–765.

Bussiere, Matthieu, and Marcel Fratzscher, 2004, “Financial Openness and Growth: Short-Run Gain, Long-Run Pain?” ECB Working Paper 348 (Frankfurt, European Central Bank).

Caballero, Ricardo J., and Arvind Krishnamurthy, 2001, “International and Domestic Collateral Constraints in a Model of Emerging Market Crises,” Journal of Monetary Economics, Vol. 48, No. 3, pp. 513–548.

Calvo, Guillermo, Alejandro Izquierdo, and Luis-Fernando Mejía, 2004, “On the Empirics of Sudden Stops: The Relevance of Balance-sheet Effects,” NBER Working Paper 10520 (Cambridge, Massachusetts, National Bureau of Economic Research).

Calvo,Guillermo, and Ernesto Talvi, 2005, “Sudden Stop, Financial Factors, and Economic Collapse in Latin America: Learning from Argentina and Chile,” NBER Working Paper No. 11153 (Cambridge, Massachusetts, National Bureau of Economic Research).

Carkovic, Maria, and Ross Levine, 2005, “Does Foreign Direct Investment Accelerate Economic Growth?” in Does Foreign Investment Promote Development? ed. by Theodore H. Moran, Edward M. Graham, and Magnus Blomström (Washington, Institute for International Economics).

Chanda, Areendam, 2005, “The Influence of Capital Controls on Long Run Growth: Where and How Much?” Journal of Development Economics, Vol. 77, No. 2, pp. 441–466.

Chari, Anusha, and Peter Blair Henry, 2004, “Risk Sharing and Asset Prices: Evidence from a Natural Experiment,” Journal of Finance, Vol. 59, No. 3, pp. 1295–1324.

Chari, Anusha, and Peter Blair Henry, 2005, “Firm-Specific Information and the Efficiency of Investment,” University of Michigan Working Paper (Ann Arbor, University of Michigan).

Chinn, Menzie, and Hiro Ito, 2006, “What Matters for Financial Development? Capital Controls, Institutions and Interactions,” Journal of Development Economics, Vol. 81, No. 1, pp. 163–192.

Choe, Jong Il, 2003, “Do Foreign Direct Investment and Gross Domestic Investment Promote Economic Growth?” Review of Development Economics, Vol. 7, No. 1, pp. 44–57.

Claessens, Stijn, Aslí Demirgüç-Kunt, and Harry Huizinga, 2001, “How Does Foreign Entry Affect Domestic Banking Markets?” Journal of Banking and Finance, Vol. 25, No. 5, pp. 891–911.

Claessens, Stijn, and Luc Laeven, 2004, “What Drives Bank Competition? Some International Evidence,” Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking, Vol. 36, No. 3, pp. 563–583.

Clarke, George R.G., and others 2003, “Foreign Bank Entry: Experience, Implications for Developing Economies, and Agenda for Further Research,” World Bank Research Observer, Vol. 18, No. 1, pp. 25–59.

Collins, Susan M., 2007, “Comments on “Financial Globalization, Growth, and Volatility in Developing Countries”, by Eswar Prasad, Kenneth Rogoff, Shang-Jin Wei, and M. Ayhan Kose,” in Globalization and Poverty, ed. by Ann Harrison (Chicago, University of Chicago Press), pp. 510–516.

Cornelius, Peter K. and Bruce Kogut, eds., 2003, Corporate Governance and Capital Flows in a Global Economy (New York, Oxford University Press).

De Mello, Luiz, 1999, “Foreign Direct Investment-Led Growth: Evidence from Time Series and Panel Data,” Oxford Economic Papers, Vol. 51, No. 1, pp. 133–151.

Desai, Mihir C., Fritz, and James R. Hines Jr ., 2004, “Capital Controls, Liberalizations and Foreign Direct Investment,” NBER Working Paper No. 10337 (Cambridge, Massachusetts, National Bureau of Economic Research).

Desai, Padma, and Pritha Mitra, 2004, “Why Do Some Countries Recover More Readily from Financial Crises?” paper presented at the IMF Conference in honor of Guillermo A. Calvo, International Monetary Fund, Washington, April 15–16.

Diamond, Douglas, and Raghuram Rajan, 2001, “Banks, Short Term Debt, and Financial Crises: Theory, Policy Implications, and Applications,” Proceedings of Carnegie Rochester Series on Public Policy, Vol. 54, No. 1, pp. 37–71.

Doidge, C., Andrew Karolyi, and René Stulz, 2005, “Why Do Countries Matter So Much More for Corporate Governance?” Ohio State University Working Paper.

Durham, J.B., 2004, “Absorptive Capacity and the Effects of Foreign Direct Investment and Equity Foreign Portfolio Investment on Economic Growth,” European Economic Review, Vol. 48, No. 2, pp. 285–306.

Easterly, William, Roumeen Islam, and Joseph E. Stiglitz, 2001, “Shaken and Stirred: Explaining Growth Volatility,” in Annual World Bank Conference on Development Economics, ed. by B. Pleskovic and N. Stern (Washington, World Bank).

Edison, Hali, Ross Levine, Luca Ricci, and Torsten Sløk, 2002, “International Financial Integration and Economic Growth,” Journal of International Monetary and Finance, Vol. 21, No. 6, pp. 749–776.

Edison, Hali J., and Francis E. Warnock, 2003, “A Simple Measure of the Intensity of Capital Controls,” Journal of Empirical Finance, Vol. 10, No. 1/2, pp. 81–103.

Edison, Hali J., Michael Klein, Luca Ricci, and Torsten Sløk, 2004, “Capital Account Liberalization and Economic Performance: Survey and Synthesis,” IMF Staff Papers, Vol. 51, No. 2, pp. 220–256.

Edwards, Sebastian, 2001, “Capital Mobility and Economic Performance: Are Emerging Economies Different?” NBER Working Paper No. 8076 (Cambridge, Massachusetts, National Bureau of Economic Research).

Edwards, Sebastian, 2004, “Financial Openness, Sudden Stops, and Current Account Reversals,” NBER Working Paper No. 10277 (Cambridge, Massachusetts, National Bureau of Economic Research).

Edwards, Sebastian, 2005, “Capital Controls, Sudden Stops, and Current Account Reversals,” NBER Working Paper No. 11170 (Cambridge, Massachusetts, National Bureau of Economic Research).

Edwards, Sebastian, 2008, “Financial Openness, Currency Crises and Output Losses,” in Strengthening Global Financial Markets, ed. by Sebastian Edwards and Márcio G.P. Garcia (Chicago, University of Chicago Press), pp. 97–120.

Eichengreen, Barry J., 2001, “Capital Account Liberalization: What Do Cross-Country Studies Tell Us?” World Bank Economic Review, Vol. 15, No. 3, pp. 341–365.

Eichengreen, Barry J., and David A. Leblang, 2003, “Capital Account Liberalization and Growth: Was Mr. Mahathir Right?” NBER Working Paper No. 9427 (Cambridge, Massachusetts, National Bureau of Economic Research).

Eichengreen, Barry J., Ricardo Hausmann, and Ugo Panizza, 2006, “The Pain of Original Sin,” in Other People's Money, ed. by Barry Eichengreen and Ricardo Hausmann (Chicago, University of Chicago Press).

Faria, André, and Paolo Mauro, 2005, “Institutions and the External Capital Structure of Countries,” IMF Working Paper 04/236 (Washington, International Monetary Fund).

Fischer, Stanley, 1998, “Capital Account Liberalization and the Role of the IMF,” in Should the IMF Pursue Capital-Account Convertibility? Essays in International Finance 207 (Princeton, New Jersey, Princeton University).

Forbes, Kristin, 2005a, “The Microeconomic Evidence on Capital Controls: No Free Lunch,” NBER Working Paper No. 11372 (Cambridge, Massachusetts, National Bureau of Economic Research).

Forbes, Kristin, 2005b, “Capital Controls: Mud in the Wheels of Market Efficiency,” Cato Journal, Vol. 25, No. 1, pp. 153–166.

Frankel, Jeffrey, 1992, “Measuring International Capital Mobility: A Review,” American Economic Review, Vol. 82, No. 2, pp. 197–202.

Frankel, Jeffrey, and Eduardo A. Cavallo, 2004, “Does Openness to Trade Make Countries More Vulnerable to Sudden Stops or Less? Using Gravity to Establish Causality,” NBER Working Paper No. 10957 (Cambridge, Massachusetts, National Bureau of Economic Research).

Gelos R., Gaston, and Shang-Jin Wei, 2005, “Transparency and International Portfolio Holdings,” Journal of Finance, Vol. 60, No. 6, pp. 2987–3020.

Gertler, Mark, and Kenneth Rogoff, 1990, “North-South Lending and Endogenous Domestic Capital Market Inefficiencies,” Journal of Monetary Economics, Vol. 26, pp. 245–266.

Glick, Reuven, and Michael Hutchison, 2001, “Banking and Currency Crises: How Common Are Twins?” in Financial Crises in Emerging Markets, ed. by Reuven Glick, Ramon Moreno, and Mark M. Spiegel (New York, Cambridge University Press).

Glick, Reuven, Xueyan Guo, and Michael Hutchison, 2006, “Currency Crises, Capital Account Liberalization and Selection Bias,” Review of Economics and Statistics, Vol. 88, No. 2, pp. 698–714.

Goldberg, Linda, 2004, “Financial-Sector Foreign Direct Investment and Host Countries: New and Old Lessons,” NBER Working Paper No. 10441 (Cambridge, Massachusetts, National Bureau of Economic Research).

Gordon, Roger, and A. Lans Bovenberg, 1996, “Why is Capital so Immobile Internationally? Possible Explanations and Implications for Capital Income Taxation,” American Economic Review, Vol. 86, No. 5, pp. 1057–1075.

Görg, Holger, and David Greenaway, 2004, “Much Ado about Nothing? Do Domestic Firms Really Benefit from Foreign Direct Investment? World Bank Research Observer, Vol. 19, No. 2, pp. 171–197.

Gourinchas, Pierre-Olivier, and Olivier Jeanne, 2006, “The Elusive Gains from International Financial Integration,” Review of Economic Studies, Vol. 73, No. 3, pp. 715–741.

Grilli, Vittorio, and Gian Maria Milesi-Ferretti, 1995, “Economic Effects and Structural Determinants of Capital Controls,” IMF Staff Papers, Vol. 42, No. 3, pp. 517–551.

Guidotti, Pablo E., Federico Sturzenegger, and Agustín Villar, 2004, “On the Consequences of Sudden Stops,” Economía, Vol. 4 (Spring), pp. 171–214.

Gupta, Nandini, and Kathy Yuan, 2005, “On the Growth Effects of Liberalizations,” Indiana University Working Paper.

Haddad, Mona, and Ann Harrison, 1993, “Are There Positive Spillovers from Direct Foreign Investment? Evidence from Panel Data for Morocco,” Journal of Development Economics, Vol. 42, No. 1, pp. 51–74.

Hall, Robert E., and Charles I. Jones, 1999, “Why Do Some Countries Produce So Much More Output Per Worker Than Others?” Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 114, No. 1, pp. 83–116.

Hammel, Eliza, 2006, “Stock Market Liberalization and Industry Growth,” (unpublished; Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Business School).

Haveman, Jon D., Vivian Lei, and Janet S. Netz, 2001, “International Integration and Growth: A Survey and Empirical Investigation,” Review of Development Economics, Vol. 5, No. 2, pp. 289–311.

Henry, Peter B., 2000a, “Stock Market Liberalization, Economic Reform, and Emerging Market Equity Prices,” Journal of Finance, Vol. 55, No. 2, pp. 529–564.

Henry, Peter B., 2000b, “Do Stock Market Liberalizations Cause Investment Booms?” Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 58, No. 1–2, pp. 301–334.

Henry, Peter B., 2007, “Capital Account Liberalization: Theory, Evidence, and Speculation,” Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. 45, No. 4, pp. 887–935.

Hermes, Niels, and Robert Lensink, 2003, “Foreign Direct Investment, Financial Development and Economic Growth,” Journal of Development Studies, Vol. 40, No. 1, pp. 142–163.

Hines, James R. Jr., 1995, “Forbidden Payment: Foreign Bribery and American Business After 1977,” NBER Working Paper No. 5266 (Cambridge, Massachusetts, National Bureau of Economic Research).

Husain, Aasim, Ashoka Mody, and Kenneth Rogoff, 2004, “Exchange Rate Regime Durability and Performance in Developing Versus Advanced Economies,” Journal of Monetary Economics, Vol. 52, No. 1, pp. 35–64.

Hutchinson, Michael, and Ilan Noy, 2005, “How Bad Are the Twins? Output Costs of Currency and Banking Crises,” Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, Vol. 37, No. 4, pp. 725–752.

Ishii, Shogo, and others 2002, Capital Account Liberalization and Financial Sector Stability, IMF Occasional Paper 211 (Washington, International Monetary Fund).

Javorcik, Beata S., 2004, “Does Foreign Direct Investment Increase the Productivity of Domestic Firms? In Search of Spillovers through Backward Linkages,” American Economic Review, Vol. 94, No. 3, pp. 605–627.

Jeanne, Olivier, 2003, “Why Do Emerging Economies Borrow in Foreign Currency?” IMF Working Paper 03/177 (Washington, International Monetary Fund).

Johnson, Simon, and Todd Mitton, 2002, “Cronyism and Capital Controls: Evidence from Malaysia,” Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 67, No. 2, pp. 351–382.

Jones, Benjamin F., and Benjamin A. Olken, 2008, “The Anatomy of Start-Stop Growth,” Review of Economics and Statistics, Vol. 90, No. 3, pp. 582–587.

Kalemli-Ozcan, Sebnem, Bent Sorensen, and Oved Yosha, 2003, “Risk Sharing and Industrial Specialization: Regional and International Evidence,” American Economic Review, Vol. 93, No. 3, pp. 903–918.

Kaminsky, Graciela, and Sergio Schmukler, 2003, “Short-Run Pain, Long-Run Gain: The Effects of Financial Liberalization,” NBER Working Paper 9787 (Cambridge, MA: National Bureau for Economic Research).

Karolyi, George Andrew, and René M. Stulz, 2003, “Are Assets Priced Locally or Globally?” in Handbook of the Economics of Finance, ed. by Milton Harris George and René M. Stulz (Elsevier, North-Holland).

Kaufmann, Daniel, Kraay Aart, and Mastruzzi Massimo, 2006, “Governance Matters V: Aggregate and Individual Governance Indicators for 1996–2005,” Policy Research Working Paper Series 4012 (Washington, World Bank).

Kim, E. Han, and Vijay Singal, 2000, “Stock Market Openings: Experience of Emerging Economies,” Journal of Business, Vol. 73, No. 1, pp. 25–66.

Klein, Michael, 2005, “Capital Account Liberalization, Institutional Quality and Economic Growth: Theory and Evidence,” NBER Working Paper No. 11112 (Cambridge, Massachusetts, National Bureau of Economic Research).

Klein, Michael, and Giovanni Olivei, 2006, “Capital Account Liberalization, Financial Depth, and Economic Growth,” Working Paper (unpublished; Boston, Tufts University).

Kose, M. Ayhan, Eswar S. Prasad, and Ashley Taylor, forthcoming, “Thresholds in the Process of International Financial Integration,” IMF Working Paper (Washington, International Monetary Fund).

Kose, M. Ayhan, Eswar S. Prasad, and Marco E. Terrones, 2003, “Financial Integration and Macroeconomic Volatility,” IMF Staff Papers, Vol. 50 (Special Issue), pp. 119–142.

Kose, M. Ayhan, EswarS. Prasad, and Marco E. Terrones, 2004, “Volatility and Comovement in an Integrated World Economy: An Exploration,” in Macroeconomic Policies in the World Economy, ed. by Horst Siebert (Berlin, Springer-Verlag).

Kose, M. Ayhan, Eswar S. Prasad and, and Marco E. Terrones, 2005, “Growth and Volatility in an Era of Globalization,” IMF Staff Papers, Vol. 52 (Special Issue), pp. 31–63.

Kose, M. Ayhan, EswarS. Prasad, and Marco E. Terrones, 2006, “How Do Trade and Financial Integration Affect the Relationship Between Growth and Volatility?” Journal of International Economics, Vol. 69, No. 1, pp. 176–202.

Kose, M. Ayhan, Eswar S. Prasad, and MarcoE. Terrones, 2008, “Does Openness to International Financial Flows Raise Productivity Growth?” IMF Working Paper 08/242 (Washington, International Monetary Fund).

Kose, M. Ayhan, Eswar S. Prasad, Kenneth Rogoff, and Shang-Jin Wei, 2006, “Financial Globalization: A Reappraisal,” NBER Working Paper No. 12484 (Cambridge, Massachusetts, National Bureau of Economic Research).

Kose, M. Ayhan, Guy Meredith, and Christopher Towe, 2005, “How Has NAFTA Affected the Mexican Economy? Review and Evidence,” in Monetary Policy and Macroeconomic Stabilization in Latin America, ed. by Rolf J. Langhammer and Lucio Vinhas de Souza (Berlin, Springer-Verlag).

Kraay, Aart, 1998, “In Search of the Macroeconomic Effects of Capital Account Liberalization,” (unpublished; Washington, World Bank).

Krugman, Paul, 2002, “Crises: The Price of Globalization?” paper presented at 2000 Symposium on Global Economic Integration, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City.

Lane, Philip R., and Gian Maria Milesi-Ferretti, 2001, “The External Wealth of Nations: Measures of Foreign Assets and Liabilities for Industrial and Developing Nations,” Journal of International Economics, Vol. 55, No. 2, pp. 263–294.

Lane, Philip R., and GianMaria Milesi-Ferretti, 2006, “The External Wealth of Nations Mark II: Revised and Extended Estimates of Foreign Assets and Liabilities, 1970–2004,” IMF Working Paper 06/69 (Washington, International Monetary Fund).

Leblebicioglu, Asli, 2006, “Financial Integration, Credit Market Imperfections and Consumption Smoothing,” North Carolina State University Working Paper.

Lensink, Robert, and Oliver Morrissey, 2006, “Foreign Direct Investment: Flows, Volatility, and the Impact on Growth,” Review of International Economics, Vol. 14, No. 3, pp. 478–493.

Levchenko, Andrei, 2005, “Financial Liberalization and Consumption Volatility in Developing Countries,” IMF Staff Papers, Vol. 52, No. 2, pp. 237–259.

Levine, Ross, 2001, “International Financial Integration and Economic Growth,” Review of International Economics, Vol. 9, No. 4, pp. 684–698.

Levine, Ross, 2005, “Finance and Growth: Theory and Evidence,” in Handbook of Economic Growth, ed. by Philippe Aghion and Steven Durlauf (Amsterdam, Elsevier Science).

Levine, Ross, and Sara Zervos, 1998, “Capital Control Liberalization and Stock Market Development,” World Development, Vol. 26, No. 7, pp. 1169–1183.

Lewis, Karen K., 1999, “Trying to Explain Home Bias in Equities and Consumption,” Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. 37 (June), pp. 571–608.

Li, Zhen, 2003, “Equity Market Liberalization and Economic Performance,” Princeton University Working Paper.

Lipsey, Robert E., 2004, “Home and Host Country Effects of FDI,” in Challenges to Globalization, ed. by Robert E. Baldwin and L. Alan Winters (Chicago, University of Chicago Press), pp. 333–379.

Lipsey, Robert E., and Fredrik Sjöholm, 2005, “The Impact of Inward FDI on Host Countries: Why Such Different Answers?” in Does Foreign Investment Promote Development? ed. by Theodore H. Moran, Edward M. Graham, and Magnus Blomström (Washington, Institute for International Economics).

López-Córdova, J. Ernesto, 2003, “NAFTA and Manufacturing Productivity in Mexico,” Economía, Vol. 4 (Fall), pp. 55–98.

Lucas, Robert E., 1987, Models of Business Cycles (Oxford, Blackwell Publishing Ltd.).

Lucas, Robert E. Jr., 1990, “Why Doesn’t Capital Flow from Rich to Poor Countries,” American Economic Review, Vol. 80, No. 2, pp. 92–96.

Magud, Nicolas, and Carmen Reinhart, 2007, “Capital Controls: An Evaluation,” in International Capital Flows, ed. by Sebastian Edwards (Chicago, University of Chicago Press), pp. 645–674.

Martin, Philippe, and Hélène Rey, 2006, “Globalization and Emerging Markets: With or Without Crash?” American Economic Review, Vol. 96, No. 5, pp. 1631–1651.

Martinez, Lorenza, Aaron Tornell, and Frank Westermann, 2004, “The Positive Link Between Financial Liberalization Growth and Crises,” NBER Working Paper No. 10293 (Cambridge, Massachusetts, National Bureau of Economic Research).

Mauro, Paolo, Nathan Sussman, and Yishay Yafeh, 2006, Emerging Markets and Financial Globalization: Sovereign Bond Spreads in 1870–1913 and Today (New York, Oxford University Press).

McKenzie, David J., 2001, “The Impact of Capital Controls on Growth Convergence,” Journal of Economic Development, Vol. 26, No. 1, pp. 1–24.

Melitz, Marc J., 2005, “Comment,” in Does Foreign Investment Promote Development? ed. by Theodore H. Moran, Edward M. Graham, and Magnus Blomström (Washington, Institute for International Economics).

Mendoza, Enrique G., Vincenzo Quadrini, and José-Victor Ríos-Rull, 2007, “On the Welfare Implications of Financial Globalization without Financial Development,” NBER Working Paper No. 13412 (Cambridge, Massachusetts, National Bureau of Economic Research).

Miniane, Jacques, 2004, “A New Set of Measures on Capital Account Restrictions,” IMF Staff Papers, Vol. 51, No. 2, pp. 276–308.

Mishkin, Frederic S., 2008, The Next Great Globalization: How Disadvantaged Nations Can Harness Their Financial Systems to Get Rich (Princeton, New Jersey, Princeton University Press).

Mitton, Todd, 2006, “Stock Market Liberalization and Operating Performances at the Firm Level,” Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 81, No. 3, pp. 625–647.

Mody, Ashoka, and Antu Panini Murshid, 2005, “Growing Up With Capital Flows,” Journal of International Economics, Vol. 65, No. 1, pp. 249–266.

Moran, Theodore H., Edward M. Graham, and Magnus Blomström, eds., 2005, Does Foreign Direct Investment Promote Development? (Washington, Institute for International Economics).

Morck, Randall, Daniel Wolfenzon, and Bernard Yeung, 2004, “Corporate Governance, Economic Entrenchment and Growth,” Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. 43, No. 3, pp. 657–722.

Obstfeld, Maurice, 1994, “Risk-taking, Global Diversification, and Growth,” American Economic Review, Vol. 84, No. 5, pp. 1310–1329.

Obstfeld, Maurice, and Kenneth Rogoff, 1995, “The Mirage of Fixed Exchange Rates,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 9, No. 4, pp. 73–96.

Obstfeld, Maurice, and Kenneth Rogoff, 2004, Foundations of International Macroeconomics (Cambridge, Massachusetts, MIT Press).

Obstfeld, Maurice, and Alan M. Taylor, 2004, Global Capital Markets: Integration, Crisis, and Growth (Cambridge, United Kingdom, Cambridge University Press).

O’Donnell, Barry, 2001, “Financial Openness and Economic Performance,” (unpublished; Trinity College Dublin).

Pallage, Stephane, and Michel A. Robe, 2003, “On the Welfare Cost of Economic Fluctuations in Developing Countries,” International Economic Review, Vol. 44, No. 2, pp. 677–698.

Prasad, Eswar S., Kenneth Rogoff, Shang-Jin Wei, and M. Ayhan Kose, 2003, Effects of Financial Globalization on Developing Countries: Some Empirical Evidence, IMF Occasional Paper 220 (Washington, International Monetary Fund).

Prasad, Eswar, and Shang-Jin Wei, 2007, “The Chinese Approach to Capital Inflows: Patterns and Possible Explanations,” in International Capital Flows, ed. by Sebastian Edwards (Chicago, University of Chicago Press), pp. 421–480.

Quinn, Dennis, 1997, “The Correlates of Changes in International Financial Regulation,” American Political Science Review, Vol. 91 (September), pp. 531–551.

Quinn, Dennis, 2003, “Capital Account Liberalization and Financial Globalization, 1890–1999: A Synoptic View,” International Journal of Finance and Economics, Vol. 8, No. 3, pp. 189–204.

Quinn, Dennis, and A. Maria Toyoda, 2008, “Does Capital Account Liberalization Lead to Growth?” Review of Financial Studies, Vol. 21, No. 3, pp. 1403–1449.

Quinn, Dennis, Carla Inclan, and A. Maria Toyoda, 2001, “How and Where Capital Account Liberalization Leads to Economic Growth,” paper presented at the 2001 Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association, San Francisco.

Rajan, Raghuram, and Luigi Zingales, 2003, “The Great Reversals: The Politics of Financial Development in the 20th Century,” Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 69 (July), pp. 5–50.

Razin, Assaf, and Andrew K. Rose, 1994, “Business-Cycle Volatility and Openness: An Exploratory Cross-Sectional Analysis,” in Capital Mobility: The Impact on Consumption, Investment, and Growth, ed. by Leonardo Leiderman and Assaf Razin (Cambridge, United Kingdom, Cambridge University Press).

Reinhart, Carmen M., and Kenneth Rogoff, 2004, “Serial Default And The ‘Paradox’ of Rich To Poor Capital Flows,” American Economic Review, Vol. 94, No. 2, pp. 52–58.

Reisen, Helmut, and Marcelo Soto, 2001, “Which Types of Capital Inflows Foster Developing-Country Growth?” International Finance, Vol. 4, No. 1, pp. 1–14.

Rodrik, Dani, 1998, “Who Needs Capital-Account Convertibility?” in Essays in International Finance, Vol. 207 (Princeton, New Jersey, Princeton University).

Schmukler, Sergio L., 2004, “Financial Globalization: Gain and Pain for Developing Countries,” Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta Economic Review (Second Quarter), pp. 39–66.

Stiglitz, Joseph, 2000, “Capital Market Liberalization, Economic Growth, and Instability,” World Development, Vol. 28, No. 6, pp. 1075–1086.

Stiglitz, Joseph, 2002, Globalization and Its Discontents (New York, W.W. Norton and Company).

Stiglitz, Joseph, 2004, “Capital-Market Liberalization, Globalization, and the IMF,” Oxford Review of Economic Policy, Vol. 20, No. 1, pp. 57–71.

Stulz, René, 1999a, “International Portfolio Flows and Security Markets,” in International Capital Flows, NBER Conference Report Series (Chicago and London, University of Chicago Press).

Stulz, René, 1999b, “Globalization of Equity Markets and the Cost of Capital,” NBER Working Paper No. 7021 (Cambridge, Massachusetts, National Bureau of Economic Research).

Stulz, René, 2005, “The Limits of Financial Globalization,” Journal of Finance, Vol. 60, No. 4, pp. 1595–1637.

Summers, Lawrence H., 2000, “International Financial Crises: Causes, Prevention, and Cures,” American Economic Review, Vol. 90, No. 2, pp. 1–16.

Tytell, Irina, and Shang-Jin Wei, 2004, “Does Financial Globalization Induce Better Macroeconomic Policies?” IMF Working Paper 04/84 (Washington, International Monetary Fund).

Vanassche, Ellen, 2004, “The Impact of International Financial Integration on Industry Growth,” (unpublished; Katholieke Universiteit Leuven).

Van Wincoop, Eric, 1999, “How Big are Potential Welfare Gains from International Risk Sharing?” Journal of International Economics, Vol. 47, No. 1, pp. 109–135.

Vlachos, Jonas, and Daniel Waldenström, 2005, “International Financial Liberalization and Industry Growth,” International Journal of Finance and Economics, Vol. 10, No. 3, pp. 263–284.

Wyplosz, Charles, 2004, “Financial Instability in Emerging Market Countries: Causes and Remedies,” paper presented at the Forum on Debt and Development (FONDAD) Conference “Stability, Growth and the Search for a New Development Agenda: Reconsidering the Washington Consensus,” Santiago, Chile.

Additional information

*M. Ayhan Kose is a senior economist with the IMF Research Department; Eswar Prasad is the Nandlal P. Tolani Senior Professor of Trade Policy at Cornell University and a Senior Fellow at the Brookings Institution; Kenneth Rogoff is the Thomas D. Cabot Professor of Public Policy and Professor of Economics at Harvard University; and Shang-Jin Wei is the N.T. Wang Professor of Chinese Business and Economy in the Graduate School of Business at Columbia University. The authors are grateful for helpful comments from numerous colleagues and participants at various seminars where earlier versions of this paper were presented. Lore Aguilar, Cigdem Akin, Dionysios Kaltis, and Ashley Taylor provided excellent research assistance.

Data Appendix

Data Appendix

This appendix lists the countries included in the analysis and also indicates the acronyms used for each country. The full sample of 71 countries is divided into three groups.Footnote 48

Advanced Economies

The 21 advanced industrial economies in our sample are Australia (AUS), Austria (AUT), Belgium (BEL), Canada (CAN), Denmark (DNK), Finland (FIN), France (FRA), Germany (DEU), Greece (GRC), Ireland (IRL), Italy (ITA), Japan (JPN), Netherlands (NLD), New Zealand (NZL), Norway (NOR), Portugal (PRT), Spain (ESP), Sweden (SWE), Switzerland (CHE), United Kingdom (GBR), and the United States (U.S.A.).

Emerging Market Economies

This group includes 20 countries—Argentina (ARG), Brazil (BRA), Chile (CHL), China (CHN), Colombia (COL), Egypt (EGY), India (IND), Indonesia (IDN), Israel (ISR), Korea (KOR), Malaysia (MYS), Mexico (MEX), Pakistan (PAK), Peru (PER), Philippines (PHL), Singapore (SGP), South Africa (ZAF), Thailand (THA), Turkey (TUR), and Venezuela (VEN).

Other Developing Economies

This group has 30 countries—Algeria (DZA), Bangladesh (BGD), Bolivia (BOL), Cameroon (CMR), Costa Rica (CRI), Dominican Republic (DOM), Ecuador (ECU), El Salvador (SLV), Fiji (FJI), Ghana (GHA), Guatemala (GTM), Honduras (HND), Iran (IRN), Jamaica (JAM), Kenya (KEN), Malawi (MWI), Mauritius (MUS), Nepal (NPL), Niger (NER), Papua New Guinea (PNG), Paraguay (PRY), Senegal (SEN), Sri Lanka (LKA), Tanzania (TZA), Togo (TGO), Trinidad and Tobago (TTO), Tunisia (TUN), Uruguay (URY), Zambia (ZMB), and Zimbabwe (ZWE).