Abstract

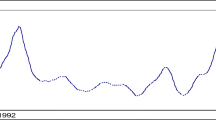

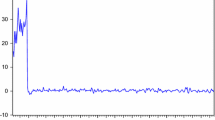

We investigate the persistence in the inflation series for 13 OECD countries that explicitly adopted an inflation targeting (IT) regime before 1992. Mean reversion and stationarity as well as mean reversion and non-stationarity exist in the pre-IT period, while mean reversion and stationarity characterize the post-IT period. Inflation exhibits fractional integration behavior over the entire sample period, the pre-IT period, and, in most cases, also in the post-IT period. The adoption of IT coincides with a structural break in all inflation series and marks a decrease in the point estimates of inflation persistence in most countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Recent contributions on inflation persistence in the US include Kumar and Okimoto [2007], Pivetta and Reis [2007], and Mehra and Reilly [2009]. Beechey and Österholm [2009], Batini [2006] and Meller and Nautz [2012] consider inflation persistence in the euro area, while Gadea and Mayoral [2006] examine inflation persistence in 21 OECD countries

Whether inflation follows a stationary or nonstationary process possesses theoretical implications, since a number of macroeconomic models [Dornbusch 1976; Taylor 1979, 1980; Calvo 1983; and Ball 1993] assume stationary inflation. Additionally, models such as Fuhrer and Moore [1995] and Blanchard and Galí [2007] suggest that inflation persistence captures structural characteristics of the economy that do not likely respond to policy actions. Thus, a policy of IT should exert no effect on inflation persistence. Others such as Batini [2006], Beechey and Österholm [2009], Benati [2008], and Mehra and Reilly [2009] present evidence that inflation persistence varies across monetary regimes

Examples include Nelson and Plosser [1982], Fuhrer and Moore [1995], Cogley and Sargent [2001], Stock [2001], Cecchetti and Debelle [2006], Pivetta and Reis [2007], and Zhang et al. [2008] for the US; O’Reilly and Whelan [2005] and Beechey and Österholm [2009] for Europe and Levin and Piger [2004] and Levin et al. [2004] for a group of OECD countries. Barsky [1987], Ball and Cecchetti [1990], and Brunner and Hess [1993] suggest that the US inflation contains a unit root. The unit-root property appears to occur in a wide array of countries examined in O’Reilly and Whelan [2005] and Cecchetti et al. [2007].

Baillie [1996] provides an extensive review of the concepts of fractional integration in economic series. Long-memory processes are defined in both time and frequency domains. In the time domain, a process exhibits long memory, if its autocorrelation function, k=1, 2, …, decreases at a hyperbolic rate rather than the exponential decay in a covariance-stationary ARMA process. In the frequency domain, the spectrum for a long-memory process diverges to infinity at the zero frequency. In practical applications, long memory emerges when the series possesses a pole on a part of the spectrum close to the zero frequency [Granger and Joyeux 1980].

The misspecification of the short-run dynamics of the ARFIMA model may invalidate the estimation of the fractional integration parameter [Gil-Alana 2004]. The task of identifying p and q for an ARMA process by a simple analysis of the autocorrelation and partial autocorrelation functions proves nearly impossible. Schmidt and Tscherning [1993], Crato and Ray [1996], and Smith et al. [1997] consider various information criteria and assess, by Monte Carlo simulations, the performance of these criteria for a fractionally integrated true model against ARMA and ARFIMA alternative models. Their results suggest that for an ARFIMA(p, d, q) data-generating process (DGP), the identification of the true model may not occur for small or moderate sample size.

We transform the seasonally adjusted price data P t into annualized monthly (quarterly) percentage rate of inflation using π t =12 × 100log(P t /P t−1) for monthly data and π t =4 × 100log(P t /P t−1) for quarterly data.

Prior to switching to IT, six of the 13 countries in the sample (Chile, Iceland, Israel, Norway, Sweden, and the UK) used exchange rates as nominal anchors in stabilization programs, while four (South Korea, Mexico, South Africa, and Switzerland) used the money supply. Australia, Canada, and New Zealand did not specify a nominal anchor before switching to IT.

Baillie [1996] considers four possible outcomes when considering the PP and KPSS tests jointly. First, reject the PP, but not the KPSS statistic, which provides evidence of a stationary series. Second, reject the KPSS, but not the PP statistic, suggesting a unit-root process. Third, do not reject both statistics, suggesting insufficient information on the long-memory characteristics of the series. Fourth, reject both statistics, which provides evidence of a process between I(0) and I(1) or a fractionally integrated process.

The PP test uses Newey–West [1987] standard errors to account for serial correlation and adopts lags chosen deterministically following the rule of thumb int[4(T/100)2/9] [Newey and West 1994]. The KPSS test uses the quadratic spectral kernel. Andrews [1991] and Newey and West [1994] indicate that the latter kernel yields more accurate estimates of the long-run variance than the Bartlett kernel in finite samples. The bandwidth comes from an automatic bandwidth selection routine. Hobijn et al. [2004] find that the combination of the automatic bandwidth selection and the quadratic spectral kernel yields the best small sample test performance in Monte Carlo simulations.

Sample autocorrelations also indicate long memory as all inflation series reveal a slow rate of decay. None exhibit exponential decay like stationary data. For Chile, Israel, and Mexico, the autocorrelations fall at a faster rate, while those corresponding to the remaining countries exhibit sinusoidal behavior that decays slowly. In either case, the autocorrelations exhibit a persistent pattern of moderately high values. Mexico displays the largest autocorrelation at lag 1 (0.92), followed by Israel (0.869) and Chile (0.864), while Switzerland displays the lowest autocorrelation at lag 30 (0.127), followed by Korea (0.154) and Australia (0.178).

From an empirical perspective, the estimates of d usually vary significantly with the choice of m. Too small an m leads to imprecise estimates because of a large standard deviation. Too large an m leads to a biased estimate of d. A large literature focuses on the choice of optimal bandwidth [Delgado and Robinson 1996 and Hurvich et al. 1998].

Hurvich et al. [1998] find that the choice of α=0.5, originally suggested by Geweke and Porter-Hudak [1983], and extensively used in empirical applications, leads to inferior performance to the optimal choice in reasonable samples.

Although Phillips [2007] suggests that we remove deterministic linear trends from the series before the application of the MLP estimator, we also estimate the persistence of the inflation series before and after the IT adoption without detrending the data at the suggestion of a referee. For all countries, the estimates of d without detrending rise relative to their values with detrended data in the pre-IT period. In the post-IT period, the estimates rise only for Canada, Israel, and Mexico. For the remaining countries, the estimates instead fall slightly using the detrended model. The Kumar-Okimoto and Hassler-Olivares test results are also generally invariant to detrending. The main exceptions are Australia (the Kumar-Okimoto test results reverse from insignificant to significant), Chile (both test results reverse from insignificant to significant), and South Africa (both test results reverse from significant to insignificant). Without detrending, the difference in the estimates of persistence for the pre- and post-IT periods are much smaller than we previously found, resulting in the failure to reject the null hypothesis of equality. We note, however, that the regression of the rate of inflation on time in these three countries as well as in the remaining ten countries produces a significantly negative linear trend estimate. We interpret this to imply that ignoring the trend in the MLP regressions leads to misspecification problems.

The frequency of observations does not affect our findings, since similar results also occur using quarterly data.

Since 1980, monetary policy implemented three distinct regimes in South Africa. From 1980 to 1989, monetary policy did not successfully contain inflation. From 1990 to 2000, a significant improvement in the performance of the South African Reserve Bank (SARB) occurred as average inflation fell from 13.06 to 8.87 percent. Since the SARB did not pursue an explicit inflation target, we can characterize this period as implicit IT. From 2000 till the present, the SARB pursues low inflation with an average inflation equal to 5.21 percent. This period differs from the second in that the SARB pursues an official and explicitly stated inflation target. Consequently, we conduct additional tests to assess the importance of the second period. First, we include the second period in the IT period. The results do not differ qualitatively from those reported in the tables. We can reject the nulls of d=0 and d=1 at the 1 percent level, and the MLP regression estimates of d vary from 0.539 for α=0.70 to 0.420 for α=0.80. Second, we test whether the explicit IT regime proved marginally more successful than the implicit targeting regime. We do not find that that occurs. We reject the null of d=1 at the 1 percent level, but we cannot reject the null of d=0 for α=0.70, 0.75, and 0.80. The MLP estimates of d vary from 0.170 for α=0.70 to 0.289 for α=0.80. Thus, persistence in the explicit IT regime, where the SARB wanted to keep inflation within the target band of 3-6 percent, exceeds its actual level under the assumption that the SARB followed the more eclectic and heterogeneous policy of the previous period. This perverse outcome could occur, ceteris paribus, because of the wide targeting band. A lower and narrower target band could improve the credibility of the SARB [Gupta and Uwilingiye 2012], causing inflationary expectations to converge to a focal point [Demertzis and Viegi 2008], resulting in an increase in monetary policy credibility and a decline in inflation persistence.

The Kumar-Okimoto and Hassler-Olivares test results are also generally invariant to detrending. The main exceptions are Australia (the Kumar-Okimoto test results reverse from insignificant to significant), Chile (both test results reverse from insignificant to significant), and South Africa (both test results reverse from significant to insignificant). Without detrending, the difference in the estimates of persistence for the pre- and post-IT periods are much smaller than we previously found, resulting in the failure to reject the null hypothesis of equality.

We thank an anonymous referee for this suggestion.

References

Agiakloglou, Cristos, Paul Newbold, and Mark Wohar. 1993. Bias in an Estimator of the Fractional Difference Parameter. Journal of Time Series Analysis, 14(3): 235–246.

Andersen, Torben G., Tim Bollerslev, Francis X. Diebold, and Paul Labys. 2003. Modeling and Forecasting Realized Volatility. Econometrica, 71(2): 579–625.

Andrews, Donald W.K. 1991. Heteroskedasticity and Autocorrelation Consistent Covariance Matrix Estimation. Econometrica, 59(3): 817–858.

Bai, Jushan. 1994. Least Squares Estimation of a Shift in Linear Processes. Journal of Time Series Analysis, 15(5): 453–470.

Bai, Jushan, and Pierre Perron. 1998. Estimating and Testing Linear Models with Multiple Structural Changes. Econometrica, 66(1): 47–78.

Bai, Jushan, and Pierre Perron. 2003. Computation and Analysis of Multiple Structural Change Models. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 18(1): 1–22.

Baillie, Richard T. 1996. Long-Memory Processes and Fractional Integration in Econometrics. Journal of Econometrics, 73(1): 5–59.

Baillie, Richard T., Ching-Fan Chung, and Margie A. Tieslau. 1996. Analyzing Inflation by the Fractionally Integrated ARFIMA-GARCH Model. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 11(1): 23–40.

Ball, Laurence. 1993. How Costly is Disinflation? The Historical Evidence. Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia. Business Review, November/December: 17–28.

Ball, Laurence, and Stephen G. Cecchetti. 1990. Inflation and Uncertainty at Short and Long Horizons. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 1: 215–254.

Ball, Laurence, and Niahm Sheridan. 2005. Does Inflation Targeting Matter? in The Inflation Targeting Debate. edited by S. Ben, Bernanke, and Michael Woodford. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 249–276.

Baum, Christopher F., John T. Barkoulas, and Mustafa Caglayan. 1999. Persistence in International Inflation Rates. Southern Economic Journal, 65(4): 900–913.

Barsky, Robert B. 1987. The Fisher Hypothesis and the Forecastability and Persistence of Inflation. Journal of Monetary Economics, 19(1): 3–24.

Batini, Nicoletta. 2006. Euro Area Inflation Persistence. Empirical Economics, 31(4): 977–1002.

Batini, Nicoletta, and Douglas Laxton. 2007. Under What Conditions Can Inflation Targeting Be Adopted? The Experience of Emerging Markets. in Monetary Policy under Inflation Targeting. edited by Frederic Mishkin, and Klaus Schmidt-Hebbel. Central Bank of Chile, 467–506.

Beechey, Meredith, and Pär Österholm. 2009. Time-varying Inflation Persistence in the Euro Area. Economic Modelling, 26(2): 532–535.

Benati, Luca. 2008. Investigating Inflation Persistence Across Monetary Regimes. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 123(3): 1005–1060.

Bernanke, Ben S., Thomas Laubach, Frederic S. Mishkin, and Adam S. Posen. 1999. Inflation Targeting: Lessons from the International Experience. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Blanchard, Olivier, and Jordi Galí. 2007. Real Wage Rigidities and the New Keynesian Model. Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking, 39(Supplement s1): 35–66.

Brito, Ricardo D., and Brianne Bystedt. 2010. Inflation Targeting In Emerging Economies: Panel Evidence. Journal of Development Economics, 91(2): 312–318.

Brunner, Allan D., and Gregory D. Hess. 1993. Are Higher Levels of Inflation Less Predictable? A State-Dependent Conditional Heteroscedasticity Approach. Journal of Business and Economic Statistics, 11(2): 187–197.

Burger, P., and M. Marinkov. 2008. Inflation Targeting and Inflation Performance in South Africa. TIPS Working Paper.

Calvo, Guillermo A. 1983. Staggered Prices in a Utility Maximization Framework. Journal of Monetary Economics, 12(3): 383–393.

Cecchetti, Stephen G., and Guy Debelle. 2006. Has the Inflation Process Changed? Economic Policy, 21(46): 311–316.

Cecchetti, Stephen G., Peter Hooper, Bruce C. Kasman, Kermit L. Schoenholtz, and Mark W. Watson. 2007. Understanding the Evolving Inflation Process. U.S. Monetary Policy Forum Report No. 1, Rosenberg Institute for Global Finance, Brandeis International Business School and Initiative on Global Financial Markets, University of Chicago Graduate School of Business.

Choi, Kyongwook, and Eric Zivot. 2007. Long Memory and Structural Changes in the Forward Discount: An Empirical Investigation. Journal of International Money and Finance, 26(3): 342–363.

Chow, Gregory C. 1960. Tests of Equality between Sets of Coefficients in Two Linear Regressions. Econometrica, 28(3): 591–605.

Cogley, Timothy, and Thomas J. Sargent. 2001. Evolving Post-World War II U.S. Inflation Dynamics. NBER Macroeconomics Annual, 16: 331–373.

Crato, Nuno, and Bonnie K. Ray. 1996. Model Selection and Forecasting for Long-Range Dependent Processes. Journal of Forecasting, 15(2): 107–125.

Delgado, Miguel A., and Peter M. Robinson. 1996. Optimal Spectral Bandwidth for Long Memory. Statistica Seneca, 6(1): 97–112.

Demertzis, Maria, and Nicola Viegi. 2008. Inflation Targets as Focal Points. International Journal of Central Banking, 4(1): 55–87.

Dickey, David A., and Wayne A. Fuller. 1979. Distributions of the Estimators for Autoregressive Time Series with a Unit Root. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 74(366): 427–431.

Diebold, Francis X., and Glenn D. Rudebusch. 1991. On the power of Dickey-Fuller Tests Against Fractional Alternatives. Economics Letters, 36(2): 155–160.

Dornbusch, Rudiger. 1976. Expectations and Exchange Rate Dynamics. Journal of Political Economy, 84(6): 1161–1176.

Erceg, Christopher J., and Andrew T. Levin. 2003. Imperfect Credibility and Inflation Persistence. Journal of Monetary Economics, 50(4): 915–944.

Fang, Wen-Shwo, Stephen M. Miller, and Chun-Shen Lee. 2010. Short- and Long-Run Differences in the Treatment Effects of Inflation Targeting on Developed and Developing Countries. Working Paper, Las Vegas: University of Nevada.

Fracasso, Andrea, Hans Genberg, and Charles Wyplosz. 2003. How Do Central Banks Write? An Evaluation of Inflation Targeting. Central Banks Geneva Reports on the World Economy Special Report 2, London: Center for Economic Policy Research.

Fuhrer, Jeffrey C. 1995. The Persistence of Inflation and the Cost of Disinflation. New England Economic Review, January/February: 3–16.

Fuhrer, Jeffrey C., and George Moore. 1995. Inflation Persistence. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 110(1): 127–160.

Gadea, María Dolores, and Laura Mayoral. 2006. The Persistence of Inflation in OECD Countries: A Fractionally Integrated Approach. International Journal of Central Banking, 2(1): 51–104.

Geweke, John, and Susan Porter-Hudak. 1983. The Estimation and Application of Long Memory Time Series Models. Journal of Time Series Analysis, 4(4): 221–237.

Gil-Alana, Luis A. 2004. Estimation of the Order Of Integration in the UK and the US Interest Rates Using Fractionally Integrated Semiparametric Techniques. European Research Studies, 7(1–2): 29–40.

Gonçalves, Carlos Eduardo S, and João M. Salles. 2008. Inflation Targeting in Emerging Economies: What Do the Data Say? Journal of Development Economics, 85(1–2): 312–318.

Gonzalo, Jesús, and Tae-Hwy Lee. 2000. On the Robustness of Cointegration Tests when the Series are Fractionally Cointegrated. Journal of Applied Statistics, 27(7): 821–827.

Granger, C.W.J., and Roselyne Joyeux. 1980. An Introduction to Long-Memory Models and Fractional Differencing. Journal of Time Series Analysis, 1(1): 15–39.

Gupta, Rangan, and Josine Uwilingiye. 2012. Comparing South African Inflation Volatility across Monetary Policy Regimes: An Application of Saphe Cracking. Journal of Developing Areas, 46(1): 45–54.

Gupta, Rangan, Alain Kabundi, and Mompho P. Modise. 2010. Has the SARB Become More Effective Post Inflation Targeting? Economic Change and Restructuring, 43(3): 187–204.

Hassler, Uwe, and Barbara Meller. 2014. Detecting Multiple Breaks in Long Memory: The Case of US Inflation. Empirical Economics, 46(2): 653–680.

Hassler, Uwe, and Maya Olivares. 2008. Long Memory and Structural Change: New Evidence from German Stock Market Returns. Discussion Paper, Frankfurt, Germany: Goethe University.

Hobijn, Bart, Philip Hans Franses, and Marius Ooms. 2004. Generalizations of the KPSS-Test for Stationarity. Statistic Neerlandica, 58(4): 483–502.

Hosking, J.R.M. 1981. Fractional Differencing. Biometrika, 68(1): 165–176.

Hsu, Yu-Chin, and Chung-Ming Kuan. 2008. Change-Point Estimation of Nonstationary I(d) Processes. Economics Letters, 98(2): 115–121.

Hurvich, Clifford M., Rohit Deo, and Julia Brodsky. 1998. The Mean Squared Error of Geweke and Porter Hudak’s Estimator of the Memory Parameter of a Long Memory Time Series. Journal of Time Series Analysis, 19(1): 19–46.

Kaseeram, Irrshad, and Eleftherios Contogiannis. 2011. The Impact of Inflation Targeting on Inflation Volatility in South Africa. The African Finance Journal, 13(Special issue 1): 34–52.

Kellard, Neil, and Nicholas Sarantis. 2008. Can Exchange Rate Volatility Explain Persistence in the Forward Premium? Journal of Empirical Finance, 15(4): 714–728.

Kiliĉ, Rehim. 2004. On the Long Memory Properties of Emerging Capital Markets: Evidence from Istanbul Stock Exchange. Applied Financial Economics, 14(13): 915–922.

Kim, Chang Sik, and Peter C.B. Phillips. 2000. Modified Log Periodogram Regression. Department of Economics, Yale University.

Kim, Chang Sik, and Peter C.B. Phillips. 2006. Log Periodogram Regression: The Nonstationary Case. Cowles Foundation. Discussion Paper (CFDP) No. 1587, Cowles Foundation for Research in Economics, Yale University.

Kouretas, Georgios P., and Mark E. Wohar. 2012. The Dynamics of Inflation: A Study of a Large Number of Countries. Applied Economics, 44(16): 2001–2026.

Kuan, Chung-Ming, and Chih-Chiang Hsu. 1998. Change-Point Estimation of Fractionally Integrated Processes. Journal of Time Series Analysis, 19(6): 693–708.

Kumar, Manmohan S., and Tatsuyoshi Okimoto. 2007. Dynamics of Persistence in International Inflation Rates. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 39(6): 1457–1479.

Kuttner, Kenneth N., and Adam S. Posen. 2001. Beyond Bipolar: A Three-Dimensional Assessment of Monetary Frameworks. International Journal of Finance and Economics, 6(4): 369–387.

Kwiatkowski, Denis, Peter C.B. Phillips, Peter Schmidt, and Yongcheol Shin. 1992. Testing the Null Hypothesis of Stationarity Against the Alternative of a Unit Root: How Sure Are We that Economic Time Series Have a Unit Root. Journal of Econometrics, 54(1–3): 159–178.

Levin, Andrew T., Fabio M. Natalucci, and Jeremy M. Piger. 2004. The Macroeconomic Effects of Inflation Targeting. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review, 86(4): 51–80.

Levin, Andrew T., and Jeremy M. Piger. 2004. Is Inflation Persistence Intrinsic in Industrial Economies? Working Paper No. 334, European Central Bank.

Li, Kai. 2002. Long Memory Versus Option-Implied Volatility Predictions. Journal of Derivatives, 9(3): 9–25.

Luu, James C., and Martin Martens. 2003. Testing the Mixture-of-Distributions Hypothesis Using “Realized” Volatility. Journal of Futures Markets, 23(7): 661–679.

Mandelbrot, Benoit B. 1971. When Can Price Be Arbitraged Efficiently? A Limit to the Validity of the Random Walk and Martingale Models. Review of Economics and Statistics, 53(3): 225–236.

Mandelbrot, Benoit B., and John W. Van Ness. 1968. Fractional Brownian Motions, Fractional Noises and Application. SIAM Review, 10(4): 422–437.

Maynard, Alex, and Peter C.B. Phillips. 2001. Rethinking an Old Empirical Puzzle: Econometric Evidence on the Forward Discount Anomaly. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 16(6): 671–708.

Mehra, Yash P., and Devin Reilly. 2009. Short-Term Headline-Core Inflation Dynamics. Economic Quarterly, 95(Summer): 289–313.

Meller, Barbara, and Dieter Nautz. 2012. Inflation Persistence in the Euro Area Before and After the European Monetary Union. Economic Modelling, 29(4): 1170–1176.

Mishkin, Federic S., and Klaus Schmidt-Hebbel. 2001. One Decade of Inflation Targeting in the World: What Do We Know and What Do We Need to Know? Working Paper No. 8397, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Nelson, Charles R., and Charles R. Plosser. 1982. Trends and Random Walks in Macroeconomics Time Series: Some Evidence and Implications. Journal of Monetary Economics, 10(2): 139–162.

Newey, Whitney K., and Kenneth D. West. 1987. A Simple, Positive Semi-Definite, Heteroskedasticity and Autocorrelation Consistent Covariance Matrix. Econometrica, 55(3): 703–708.

Newey, Whitney K., and Kenneth D. West. 1994. Automatic Lag Selection in Covariance Matrix Estimation. Review of Economic Studies, 61(4): 631–653.

O’Reilly, Gerard, and Karl Whelan. 2005. Has Euro-Area Inflation Persistence Changed Over Time? The Review of Economics and Statistics, 87(4): 709–720.

Orphanides, Athanasios, and John C. Williams. 2005. Imperfect Knowledge, Inflation Expectations, and Monetary Policy. in The Inflation-Targeting Debate. edited by Ben S. Bernanke, and Michael Woodford. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 201–234.

Pétursson, Thórarinn G. 2005. The Effects of Inflation Targeting on Macroeconomic Performance. The European Money and Finance Forum (SUERF Studies), no. 5.

Phillips, Peter C.B. 2007. Unit Root Log Periodogram Regression. Journal of Econometrics 138(1): 104–124. The original version circulated in March, 1999 as Cowles Foundation Discussion Paper (CFDP) No. 1243, Cowles Foundation for Research in Economics, Yale University.

Phillips, Peter C.B. 2005. Econometric Analysis of Fisher’s Equation. The American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 64(1): 125–168.

Phillips, Peter C.B., and Pierre Perron. 1988. Testing for a Unit Root in a Time Series Regression. Biometrika, 75(2): 335–346.

Pivetta, Frederic, and Ricardo Reis. 2007. The Persistence of Inflation in the United States. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 31(4): 1326–1358.

Rangasamy, Logan. 2009. How Persistent Is South Africa’s Inflation? Economic Research Southern Africa (ERSA) Working Paper no. 115.

Schaechter, Andrea, Mark R. Stone, and Mark Zelmer. 2000. Practical Issues in the Adoption of Inflation Targeting by Emerging Market Countries. Occasional Paper 202, International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Schmidt, Christopher M., and Rolf Tscherning. 1993. The Identification of Fractional ARIMA Models in the Presence of Long Memory. Working Paper No. 4, Germany: University of Munich.

Shimotsu, Katsumi. 2006. Simple (But Effective) Tests of Long Memory Versus Structural Breaks. Queen’s Economics Department Working Paper No. 1101.

Siklos, Pierre L. 1999. Inflation-Target Design: Changing Inflation Performance and Persistence in Industrial Countries. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review, 81(2): 47–58.

Smith, Jeremy, Nick Taylor, and Sanjay Yadav. 1997. Comparing the Bias and Misspecification in ARFIMA Models. Journal of Time Series Analysis, 18(5): 507–527.

Sowell, Fallaw. 1992. Maximum Likelihood Estimation of Stationary Univariate Fractionally Integrated Time Series Models. Journal of Econometrics, 53(1–3): 165–188.

Stock, James H. 2001. Comment on ‘Evolving Post-World War II U.S. Inflation Dynamics. NBER Macroeconomics Annual, 16: 379–387.

Taylor, John B. 1979. Staggered Wage Setting in a Macro Model. American Economic Review, 69(2): 108–113.

Taylor, John B. 1980. Output and Price Stability: An International Comparison. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 2: 109–132.

Truman, Edwin M. 2003. Inflation Targeting in the World Economy. Working Paper, Peterson Institute for International Economics.

Yigit, Taner M. 2010. Inflation targeting: An indirect approach to assess the direct impact. Journal of International Money and Finance, 29(7): 1357–1368.

Zhang, Chengsi, Denise R. Osborn, and Dong Heon Kim. 2008. The New Keynesian Phillips Curve: From Sticky Inflation to Sticky Prices. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 40(4): 667–699.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the helpful comments of two anonymous referees. Any remaining errors reflect our own work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Canarella, G., Miller, S. Inflation Persistence Before and After Inflation Targeting: A Fractional Integration Approach. Eastern Econ J 43, 78–103 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1057/eej.2015.36

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/eej.2015.36