Abstract

Fitness costs associated with resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) toxins critically impact the development of resistance in insect populations. In this study, the fitness costs in Trichoplusia ni strains associated with two genetically independent resistance mechanisms to Bt toxins Cry1Ac and Cry2Ab, individually and in combination, on four crop plants (cabbage, cotton, tobacco and tomato) were analyzed, in comparison with their near-isogenic susceptible strain. The net reproductive rate (R0) and intrinsic rate of increase (r) of the T. ni strains, regardless of their resistance traits, were strongly affected by the host plants. The ABCC2 gene-linked mechanism of Cry1Ac resistance was associated with relatively low fitness costs, while the Cry2Ab resistance mechanism was associated with higher fitness costs. The fitness costs in the presence of both resistance mechanisms in T. ni appeared to be non-additive. The relative fitness of Bt-resistant T. ni depended on the specific resistance mechanisms as well as host plants. In addition to difference in survivorship and fecundity, an asynchrony of adult emergence was observed among T. ni with different resistance mechanisms and on different host plants. Therefore, mechanisms of resistance and host plants available in the field are both important factors affecting development of Bt resistance in insects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Transgenic crops expressing the environmentally benign insecticidal toxins from Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) are now widely planted in over 70 million hectares worldwide for pest control1. However, the benefits of Bt-crops can be diminished if insects develop resistance to the Bt toxins. Bt resistance has been well documented in a number of insect pests under laboratory selections and in the field2. It is known that insect resistance to Bt toxins is often associated with fitness costs, the reduction of fitness relative to susceptible individuals, which lead to reduced competitiveness of resistant insects on non-Bt host plants and consequently critically impact the selection of Bt resistant alleles in insect populations3. Therefore, with the increasing application of Bt toxins in transgenic crops, studies on Bt resistance-associated fitness costs have been increasingly reported since the 1990s.

Bt resistance associated fitness costs have been studied on artificial diet in several lepidopteran pests, including Helicoverpa armigera4, Heliothis virescens5, Ostrinia nubilalis6, Pectinophora gossypiella7, Plutella xylostella8, Spodoptera exigua9 and Trichoplusia ni10, or on their primary host plants cabbage for P. xylostella8,11,12,13, tomato, cucumber and pepper plants for T. ni14, cotton plants for H. armigera15, H. virescens16 and P. gossypiella17, maize for Busseola fusca18, O. nubilalis19, H. zea20 and S. frugiperda21 and tobacco for S. litura22. The fitness costs can be affected by the genetic backgrounds of the insects, mechanisms of resistance, host plants, and other dietary and ecological factors7,11,12,13,14, which complicate the fitness cost analysis and could lead to spurious data interpretations3. Fitness costs associated with Bt resistance in insects often become higher when food quality decreases, e.g. feeding alternative plants3,11. In the field, insects feed on various host plants, depending on the host ranges of the insects and field situations, and most agriculturally important lepidopteran pests are polyphagous herbivores feeding on a range of host plants. Different host plants vary in their nutritional quality for insects and also vary in their insecticidal secondary metabolites that impose chemical stress on the insects, both of which could affect the fitness costs associated with insect resistance11,12,14. Therefore, to understand the fitness costs associated with Bt resistance, it is important to dissect the fitness costs associated with specific resistance mechanisms on specific host plants in insect populations in the same genetic background.

The cabbage looper, T. ni, is a highly polyphagous insect with an exceptionally broad and diverse range of host plants, including over 160 plant species in 36 families23. In T. ni, more than 70 cases of resistance to 14 different insecticides have been documented (http://www.pesticideresistance.org). More notably, T. ni is one of the only two insect pests that have developed resistance to Bt formulations in agricultural settings24. From a greenhouse-evolved Bt-resistant T. ni population, two genetically independent Bt resistance traits, Cry1Ac resistance and Cry2Ab resistance, have been isolated and introgressed into a highly homozygous susceptible laboratory T. ni strain25,26. The Cry1Ac resistance in T. ni has been identified to be conferred by the same major genetic mechanism for Cry1Ac resistance shared by several lepidopteran pests27,28,29, enabling T. ni to survive on Bt-cotton plants expressing the Cry1Ac toxin30. Combining the resistance mechanisms to Cry1Ac and Cry2Ab in T. ni allows the insects to survive on the widely planted major pyramided dual-toxin transgenic Bt-cotton plants (Bollgard II)30. The broad host range of T. ni makes this insect a pest of numerous important agricultural crops, from cruciferous vegetables to the field crop cotton23, but also provides an ideal system to study the effects of crop plants with different nutritional quality and different secondary metabolites on the fitness costs associated with specific Bt resistance mechanisms. In this study, we used the unique near-isogenic T. ni strains25,26,30,31 as a biological system to dissect the fitness costs associated with the mechanisms of Cry1Ac resistance, Cry2Ab resistance and a combination of both mechanisms of resistance to Cry1Ac and Cry2Ab in T. ni. on artificial diet, on their preferred host plant (cabbage) and on alternative host plants (cotton, tobacco and tomato).

Results

Population growth of T. ni is affected by the mechanisms of resistance to Bt and host plants

Both the Bt-susceptible Cornell strain30 and three near-isogenic T. ni strains resistant to Cry1Ac, strain GLEN-Cry1Ac-BCS25, to Cry2Ab, strain GLEN-Cry2Ab-BCS26, and to both Cry1Ac and Cry2Ab, strain GLEN-Cry1Ac+Cry2Ab-BCS30, all survived and completed their life cycles on the foliage of four host plants (cabbage, cotton, tobacco and tomato) tested. The net reproductive rate (NRR) (R0) for each strain was far greater than the critical value 1 (ranging from 31.0 to 347.9) on the four host plants. However, the NRRs were affected by both host plants and the Cry toxin resistance traits (Table 1). Compared to feeding on artificial diet as control, feeding on plant foliage reduced the population growth, showing a decrease of the R0 values from 252.3–347.9 to 31.0–98.7. On cabbage, all strains showed a similar NRR reduction to 32–35% of that on artificial diet. The T. ni strains resistant to Cry2Ab, GLEN-Cry2Ab-BCS and GLEN-Cry1Ac+Cry2Ab-BCS, showed a greater decrease of R0 (decreased to 11–18% and 13–18%, respectively for the two strains) on cotton, tobacco and tomato leaves than the Cry1Ac-resistant strain GLEN-Cry1Ac-BCS (decreased to 18–22%) and the Cornell strain (decreased to 26–35%). The decrease of fitness of T. ni associated with the resistance was relatively low on artificial diet (relative fitness w = 0.72–0.80) and cabbage (w = 0.78–0.89) but was high on cotton (w = 0.36–0.54), tobacco (w = 0.46–0.78) and tomato (w = 0.25–0.50) leaves (Table 1). The fitness cost measured by w values associated with Cry2Ab resistance was greater than that with Cry1Ac resistance on the three plants (Table 1).

Analysis of population growth of the T. ni strains using the intrinsic rate of increase (IRI) (r) (Table 2) showed similar patterns as those from the analysis based on NRR described above (Table 1). The r values for the T. ni strains on four plants were all >0, ranging from 0.116 to 0.297, indicating that the T. ni populations could grow on the foliage of the four plants. T. ni strains showed a higher reduction of r values on the foliage of cotton, tobacco and tomato plants than on cabbage and artificial diet, and the fitness cost associated with Cry2Ab resistance was greater than that with Cry1Ac resistance (Table 2).

Fecundity of T. ni is affected by the mechanisms of resistance and host plants

A generalized linear model analysis indicated that females of T. ni fed on plant foliage laid significantly less eggs than those on artificial diet (“plant effect”, df = 4, p < 2.2 × 10−16) (Table 3, Fig. S1). Feeding on cabbage had the smallest negative effect comparing to feeding on the plants tested, causing 17–22% reduction of the total number of eggs as compared to the control feeding artificial diet; while feeding on tomato foliage had the greatest effect, causing a 38–54% reduction of egg numbers. The reduction of egg laying associated with the resistance to Cry1Ac and Cry2Ab in T. ni was minimal on artificial diet (reduction of 5–8%) and cabbage (reduction of 3–8%). However, feeding the other three plants resulted in a 11–17%, 13–26% and 20–30% reduction of egg laying, respectively, in the strains GLEN-Cry1Ac-BCS, GLEN-Cry2Ab-BCS and GLEN-Cry1Ac + Cry2Ab BCS (“strain effect”, df = 3, p < 2.2 × 10−16) (Table 3, Fig. S1). The greatest reduction of egg laying observed was in the GLEN-Cry2Ab-BCS strain on tomato foliage, which also showed the most notable effect of interaction of the two factors (“plant × strain”, df = 12, p < 2.2 × 10−16) (Fig. S1).

The kinetics of egg laying were significantly affected by host plants (“plant effect”, df = 4, p < 2.2 × 10−16) and by the resistance traits (“strain effect”, df = 3, p < 2.2 × 10−16) (Fig. 1, Fig. S1). No significant difference in egg laying dynamics between the four strains was observed when the T. ni were grown on artificial diet, and on cabbage and cotton foliage (Fig. 1) (two-sample two-sided Kolmogorov-Smirnov analysis, p > 0.05). However, a significant difference was observed in Cry2Ab-resistant T. ni on tobacco (D = 9.37%, p = 0.015 for GLEN-Cry2Ab-BCS; D = 8.33%, p = 0.036 for GLEN-Cry1Ac+Cry2Ab-BCS) and on tomato (D = 8.13%, p = 0.042 for GLEN-Cry2Ab-BCS; D = 8.96%, p = 0.021 for GLEN-Cry1Ac+Cry2Ab-BCS). This is consistent with the statistically significant interaction between host plants and resistance traits by GLM analysis (“plant x strain”, df = 11, p < 2.2 10−16) (Table 3, Fig. S1). The total number of egg laying days was also significantly affected by the host plants (“plant effect”, df = 4, p = 2.3 10−14), showing a decrease of 2.6–4.1 days of egg laying days on tomato for all strains regardless of resistant trait (“strain effect”, df = 3, p = 0.61) (Fig. 1F, Fig. S1). A decrease in egg hatching rate was observed in all resistant strains (“strain effect”, df = 3, p < 2.2 10−16) (Table 3, Fig. S1). However, the level of decrease in hatchability was very minimal, with the largest reduction to be only 6.2% to 8.9% observed in eggs from the GLEN-Cry1Ac+Cry2Ab-BCS strain on cabbage and cotton plants (“plant x strain”, df = 12, p = 1.6 10−03) (Table 3, Fig. S1).

Kinetics of egg laying by females from the susceptible (white diamond, black line), Cry1Ac (cross, dotted line), Cry2Ab (grey square, grey line) and Cry1Ac-Cry2Ab resistant strains (black triangle, black line) reared on artificial diet (A), cabbage (B), cotton (C), tobacco (D) or tomato (E). (F). Total number of egg laying days for the susceptible (white), Cry1Ac (striped), Cry2Ab (grey) and Cry1Ac-Cry2Ab resistant strains (black) reared on each plant. The observations from different T. ni strains on the same plant that were not statistically different from each other are indicated by the same letter in lower case above the bars. The observations from the same T. ni strain on different plants that were not statistically different from each other are indicated by the same letter in upper case above the bars. Values are indicated as mean ± SE.

Development of T. ni is affected by the mechanisms of resistance and host plants

The duration of larval development was affected by T. ni strains (“strain effect”, df = 3, p < 2.2 10−16) and host plants (“plant effect”, df = 4, p = 5.1 10−04) without statistically significant interaction of the two factors (“plant x strain”, df = 12, p = 0.27) (Fig. S1, Table 4). The larval stage was 2.4 − 3.2, 8.3 −12.9, 8.1 − 9.9 and 6.5 − 8.8 days longer on cabbage, cotton, tobacco and tomato foliage, respectively, than that on artificial diet (Table 4). On artificial diet, the pupal stage was 8 days, regardless of the T. ni strains (“strain effect”, df = 3, p = 0.23) (Table 4). The duration of pupal stage varied within 1 day among the treatments (“plant effect”, df = 4, p = 1.0 10−10), with the only exception for the Cry2Ab resistant strains on cotton (the pupal stage was 3 days shorter than susceptible strain) (“plant x strain”, df = 12, p = 9.2 10−05) (Table 4, Fig. S1).

The gender had no significant effect on pupal weight (“sex effect”, df = 1, p = 0.84) (Fig. S1). Pupae from cabbage showed no difference in weight from those on artificial diet, while those from cotton, tobacco and tomato plants showed a 55–70% decrease in pupal weight (“plant effect”, df = 4, p = 5.2 10−02) (Table 5, Fig. S1). Similarly, the rate of adult emergence from pupae was affected by the host plants (“plant effect”, df = 4, p = 2.6 10−03) (Fig. S1), with the most significant reduction of emergence observed on tomato (64–84%) (Table 5). The sex ratio of adults varied among replications but was not affected by host plants (“plant effect”, df = 3, p = 0.15) nor by the resistance traits (“strain effect”, df = 3, p = 0.48) (Fig. S1, Table S2).

Survivorship of T. ni is affected by the mechanisms of resistance and host plants

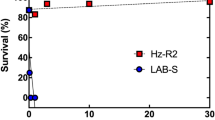

On artificial diet, 80.3% of the larvae from the susceptible strain completed pupation, but the pupation rate decreased to 39.3–49.7% on plants (“plant effect”, df = 4, p < 2.2 10−16) (Fig. 2, Fig. S1). The resistant strains had a pupation rate of 74.3–79.7% on artificial diet and of 25.3–39.7% when fed on the plant foliage. The effects of the host plants on survival of T. ni showed different larval stage specific patterns (“stage x plant”, df = 4, p < 2.2 10−16) (Fig. 2, Fig. S1). For T. ni on artificial diet, mortality mainly occurred during pre-pupation and at pupal stage (Fig. 2A). However, mortality predominantly occurred at 5th instar and pupal stage on cabbage (Fig. 2B). T. ni larvae fed on cotton had high mortality at 4th and 5th larval instars and moderate mortality (about 10%) during prepupal and pupal stages (Fig. 2C). High mortality happened at 1st and 2nd larval instars on tobacco (Fig. 2D) and at 3rd larval instar and pupal stage on tomato (Fig. 2E). The effect of different strains on mortality was also observed to be developmental stage-specific (“strain effect”, df = 3, p = 1.5 10−03) (Fig. S1), showing a generally higher mortality in GLEN-Cry2Ab-BCS and GLEN-Cry1Ac+Cry2Ab-BCS resistant strains as compared with the susceptible strain in nearly all instars on all plants (Fig. 2).

Cumulative percentage of mortality at each developmental stage for the susceptible (white), Cry1Ac (striped), Cry2Ab (grey) and Cry1Ac-Cry2Ab resistant strains (black) reared on artificial diet (A), cabbage (B), cotton (C), tobacco (D) or tomato (E). The inserts show the percentage of mortality at each stage. Values are presented as mean ± SE.

Discussion

In this study, the fitness costs associated with two independent resistance mechanisms to two agriculturally important Bt toxins, individually and in combination, on four different crop plants were determined under the same genetic background in a lepidopteran pest, using the unique near-isogenic T. ni strains in the same genetic background of a laboratory T. ni strain. The laboratory strain has been maintained on artificial diet in laboratory and is well adapted to artificial diet, which may lead to their response to plant materials different from the T. ni from field populations. However, use of T. ni strains in the genetic background of the laboratory strain helps minimize the influence on insect performance by the unknown heterogeneous backgrounds of T. ni in the field populations that may have differential preference to different host plants. This experimental approach allowed examination of fitness costs on specific host plants associated with particular resistance mechanisms in an insect pest. Mechanisms of insect resistance to Bt toxins may vary from case to case, but are known not to be insect species-specific29,32. The Cry1Ac resistant T. ni individuals can survive on Cry1Ac-broccoli and Cry1Ac-cotton plants25,30 and the resistance is conferred by a mutation in the ABCC2 gene locus region of the genome28. Such a high level of Cry1Ac resistance with genetic linkage to the ABCC2 gene has also been identified in H. virescens27, P. xylostella28 and B. mori33. Therefore, the fitness costs determined in this study may represent the characteristics of fitness costs associated with the specific resistance mechanisms to Cry1Ac and to Cry2Ab in Lepidoptera.

Similar to many lepidopteran pests, T. ni is highly polyphagous. Although the mechanisms of Cry1Ac- and Cry2Ab-resistance in T. ni are associated with fitness costs, the resistant T. ni larvae can survive and complete their life cycle on their preferred primary host plant as well as on the secondary host plants cotton, tobacco and tomato, with their NRR and IRI values (Ro and r) far above the critical values (Ro > 1; r > 0) for population growth. The fitness of T. ni was always higher on artificial diet than on the host plants tested, irrespective of the T. ni strains, which is similar to the observations made in P. xylostella8 and Pseudaletia sequax34. Cabbage is a preferred host plant for T. ni and, as a crucifer, it produces glucosinolates as major anti-herbivory metabolites; whereas tobacco, tomato and cotton plants are known to produce alkaloids (e.g. nicotine), phenolics, protease inhibitors, and other insecticidal secondary metabolites35. Among the four host plants tested, cabbage was the one on which T. ni laid the largest number of eggs, developed the fastest, had the lowest mortality and the highest pupal weight, irrespective of the resistance traits. Cabbage appears to be the best-adapted host plant for T. ni, which is in agreement with the preference of T. ni on plants of the Brassicaceae family for host plant choice. These results are also consistent with the previous report that DiPel-resistant T. ni developed faster, survived better and weighed more when feeding on cucumber (family: Brassicaceae) plants than on tomato (family: Solanaceae) and pepper (family: Piperaceae) plants14. The results in this study showed that the T. ni strains all developed more slowly on cotton, tobacco and tomato foliage than on cabbage. The slower larval development on the secondary host plants resulted in the life cycle of T. ni to be 3.6 to 7.9 days longer and in asynchrony in adult emergence and egg laying than those feeding on cabbage (Fig. 3). Such a significant difference in developmental time to reach adult emergence between the primary and secondary host plants has also been observed in S. frugiperda on maize, cotton and soybean21, in S. litura on tobacco, sweet potato, cabbage and cow pea22 and in T. ni on cucumber, tomato and pepper plants14. The slower larval development of T. ni is associated with a lower pupal weight on cotton, tobacco and tomato as compared to feeding on cabbage. Interestingly, the patterns of mortality occurrence in T. ni at different developmental stages differed when T. ni were on different host plants. The difference observed on the four plants may reflect differential adaptation of T. ni larvae to these host plants. The results from this study and previous reports of similar studies in T. ni14, H. armigera15 and P. xylostella11,13 consistently show that the level of fitness costs is affected by the host plants on which the resistant insects feed on.

Adult stage duration (dotted) was fixed at 13 days as adults were not reared until death in this study. The median, which is the number of days when 50% of total amount of eggs are laid, is indicated by a thick black line. A dotted box indicates the range of days around the median in which 50% of eggs are laid (between the 1st and 3rd quartiles).

Mechanisms of insect resistance to Cry1Ac have been studied in several species of Lepidoptera32. Cry1A resistance may involve changes of proteases that affect the proteolytic processing of toxins36, but high levels of resistance usually involve changes of a midgut receptor for Cry toxins32. The Cry1Ac resistance in T. ni is associated with down-regulation of the APN1 gene expression genetically linked to a mutation in the ABCC2 gene locus region which acts in trans28,37. At present, genetic mechanisms for Cry2Ab resistance in T. ni is unknown, but it is known that the resistance to Cry1Ac and that to Cry2Ab are conferred by two genetically independent mechanisms26,30. The results from this study determined that the Cry1Ac resistance mechanism with a genetic linkage to the ABCC2 locus is associated with a low fitness cost in T. ni. In comparison with the Cornell strain, the GLEN-Cry1Ac-BCS strain only shows a moderately extended larval development time, an increased mortality on cotton, and a slight decreased percentage of egg hatching. In contrary, the fitness costs associated with the Cry2Ab resistance mechanism were higher with significantly reduced fecundity and increased mortality. The GLEN-Cry1Ac+Cry2Ab-BCS strain is resistant to both Cry1Ac and Cry2Ab toxins, but no significant additive effect from the Cry1Ac and Cry2Ab resistance on the fitness costs was observed in this T. ni strain. Therefore, the fitness costs observed in the GLEN-Cry1Ac+Cry2Ab-BCS strain were not the result of addition of the costs associated with the two distinct resistance mechanisms. The effects of the different crop plants on the Bt resistance-associated fitness costs were determined in T. ni in this study, but the information could be extended to other lepidopterans which often have similar midgut physiology and may share the same Bt resistance mechanisms32.

The “high dose-refuge” strategy is a major tactic used to delay the development of insect resistance to Bt crops in the field38. This resistance management strategy relies on extensive mating between resistant insects from Bt crop fields and susceptible insects from non-Bt refuge zones39. The observations on adult emergence and egg laying of T. ni with a different Bt resistant trait and growing on different host plants showed both host plant-dependent and resistance trait-dependent asynchrony in adult emergence and egg laying dynamics (Fig. 3). Particularly important was the effect associated with Cry2Ab resistance in T. ni when fed on tobacco and tomato: the peak of egg laying was delayed 4–8 days, compared to the susceptible strain (Fig. 3). Given that T. ni females mostly mate within 3–5 days after emergence40, an asynchrony of adult emergence and egg laying of several days between the susceptible and resistant individuals on different plants per generation could potentially lead to significant phenological changes of the susceptible and resistant populations after multiple generations. This can be sufficient to affect the mating between resistant and susceptible insects and reduce the efficacy of the “high dose-refuge” strategy. This phenomenon might be amplified by the natural tendency of assortative mating between insects developing on the same plants and of transgenerational adaptation to the plant that can be at the basis of host plant shifts41,42. Altogether, the results from this study indicate that the relative fitness of Bt resistant insects compared to the susceptible insects depends on the specific resistance mechanisms and on host plants. Both insect resistance mechanisms and host plants available to the insects in the field are important factors affecting selection of resistance alleles in the field and therefore need be taken into account for development of resistance management strategies20,43.

Materials and Methods

Insect Strains

A highly inbred laboratory T. ni strain, the Cornell strain30, was used as the Bt susceptible control strain. A Cry1Ac resistant strain, GLEN-Cry1Ac-BCS25, a Cry2Ab resistant strain, GLEN-Cry2Ab-BCS26, and a strain resistant to both Cry1Ac and Cry2Ab, GLEN-Cry1Ac+Cry2Ab-BCS30, were used in this study to examine the fitness costs associated with the resistance traits on different crop plants. The Cry resistance traits in these three strains were originated from the greenhouse-derived GLEN-DiPel strain31 and the strains were all near-isogenic to the Cornell strain by introgression of the Cry resistance traits into the Cornell strain25,26. The T. ni strains were routinely maintained on artificial diet without exposure to Bt toxins30.

Plants

Plants of cabbage variety Quisor (Stokes Seeds, Buffalo, NY), cotton variety Stoneville 47430, tobacco variety Wisconsin 38 (provided by Dr. Susheng Gan of Cornell University) and tomato variety Better Boy (Harris Seeds, Rochester, NY) were grown in formulated soil, the Cornell Mix, in 6 L plastic pots in the greenhouse at 27 ± 2 °C under a light and dark regime of 16:8 h30.

Examination of Fitness Costs

Performance of T. ni larvae from the susceptible Cornell strain and three resistant strains was examined by rearing the larvae on artificial diet and on detached leaves of the cabbage, cotton, tobacco and tomato plants in 8.0 cm (diameter) ×6.5 cm (height) paper cups. A total of 300 neonates of each strain were placed in 30 cups (10 larvae per cup), provided with artificial diet or detached leaves of a test plant. Plant leaves were replaced daily or more frequently as necessary when the larvae reached 5th instar. The cups were placed in an insect rearing chamber at 25 ± 1 °C, 50 ± 10% relative humidity, and 16:8 h photoperiod. Larval development and mortality were recorded every 12 h till completion of pupation. Pupae were collected daily and weighed. The sex of pupae was visually determined following the criteria described by Butt and Cantu44.

For examination of fecundity, one female moth and two male moths from the same cup were placed in a wire cage (12 cm in diameter and 11 cm in height) which was wrapped with wax paper for egg collection. The moths were provided with 10% sugar solution. For each treatment, 30 “1-female+2-males” cages (one “1-female+2-males” cage for each cup) were used for replications. The wax paper was replaced daily from each cage. Eggs on the wax paper were counted and hatching of the eggs was examined daily afterwards.

Two demographic parameters, net reproductive rate (R0) and intrinsic rate of increase (r), were calculated for each strain on each test plant using the formula described by Carey45. The net reproductive rate was calculated as R0 = Nn+1/Nn, where Nn is the population quantity of the parent generation (neonate number = 300) and Nn+1 is that of the next generation. A R0 value of 1 indicates that females are having exactly enough offspring females to replace them in the next generation and R0 > 1 indicates that more daughters than mothers are present in the population. The intrinsic rate of increase was calculated as r = ln(R0)/((x * lx * mx)/R0), where x is the females age in days, lx the age-specific survival, mx the age-specific fecundity and R0 the net reproductive rate. A strictly positive r value indicates that the population size is increasing while r < 0 is indicative of a collapsing population. The relative fitness (w) of the resistant strain was calculated as the ratio of R0 or r of the resistant strain to R0 or r of the susceptible strain.

Statistical Analysis

The fitness parameters recorded from the experiments were analyzed using a generalized linear model (GLM) to measure the effect of different factors (i.e. strain, host plant) on the fitness of T. ni and the interactions between the factors. In all data analyses, the individual cups were considered as independent units to be analyzed, using the mean of data from 10 larvae in each cup or from a “1-female+2-males” for each mating group. Normality of the data was verified by using a Shapiro-Wilk test. In order to determine the most suitable distribution model for the GLM, a one-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test against the corresponding model was used. A binomial error family was used for traits expressed as percentages (hatching, emergence and survival) while a Poisson error family was used for all other traits. When a significant effect was found, an ANOVA followed by multiple pairwise comparisons of means (Tukey’s HSD test) was performed in order to determine the effect of each strain and each host plant on the fitness parameters analyzed. Pairwise comparisons of egg laying kinetics were performed with a two-sample two-sided Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. All statistical analyses were performed using the software R 3.0.246.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Wang, R. et al. Effect of crop plants on fitness costs associated with resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis toxins Cry1Ac and Cry2Ab in cabbage loopers. Sci. Rep. 6, 20959; doi: 10.1038/srep20959 (2016).

References

James, C. Global Status of Commercialized Biotech/GM Crops. In ISAAA Brief 46 (International Service for the Acquisition of Agri-Biotech Applications, 2013).

Tabashnik, B. E., Brevault, T. & Carriere, Y. Insect resistance to Bt crops: lessons from the first billion acres. Nat. Biotechnol. 31, 510–521 (2013).

Gassmann, A. J., Carriere, Y. & Tabashnik, B. E. Fitness Costs of Insect Resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis . Annu. Rev. Entomol. 54, 147–163 (2009).

Liang, G.-M. et al. Changes of inheritance mode and fitness in Helicoverpa armigera (Hubner) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) along with its resistance evolution to Cry1Ac toxin. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 97, 142–149 (2008).

Gould, F. & Anderson, A. Effects of Bacillus thuringiensis and HD-73 delta-endotoxin on growth, behavior, and fitness of susceptible and toxin-adapted strains of Heliothis virescens (Lepidoptera, Noctuidae). Environ. Entomol. 20, 30–38 (1991).

Crespo, A. L. B., Spencer, T. A., Tan, S. Y. & Siegfried, B. D. Fitness Costs of Cry1Ab Resistance in a Field-Derived Strain of Ostrinia nubilalis (Lepidoptera: Crambidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 103, 1386–1393 (2010).

Williams, J. L. et al. Fitness Cost of Resistance to Bt Cotton Linked with Increased Gossypol Content in Pink Bollworm Larvae. Plos One 6, e21863 (2011).

Shirai, Y., Tanaka, H., Miyasono, M. & Kuno, E. Low intrinsic rate of natural increase in Bt-resistant population of Diamondback Moth, Plutella xylostella (L.) (Lepidoptera: Yponomeutidae). Jpn. J. Appl. Entomol. Z. 42, 59–64 (1998).

Dingha, B. N., Moar, W. J. & Appel, A. G. Effects of Bacillus thuringiensis Cry1C toxin on the metabolic rate of Cry1C resistant and susceptible Spodoptera exigua (Lepidoptera : Noctuidae). Physiol. Entomol. 29, 409–418 (2004).

Janmaat, A. F. & Myers, J. H. Genetic variation in fitness parameters associated with resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis in male and female Trichoplusia ni . J. Invertebr. Pathol. 107, 27–32 (2011).

Raymond, B., Sayyed, A. H. & Wright, D. J. Host plant and population determine the fitness costs of resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis . Biol. Letters 3, 82–85 (2007).

Raymond, B., Sayyed, A. H. & Wright, D. J. Genes and environment interact to determine the fitness costs of resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis . P. Roy. Soc. B-Biol. Sci. 272, 1519–1524 (2005).

Raymond, B., Wright, D. J. & Bonsall, M. B. Effects of host plant and genetic background on the fitness costs of resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis . Heredity 106, 281–288 (2011).

Janmaat, A. F. & Myers, J. H. The cost of resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis varies with the host plant of Trichoplusia ni . P. Roy. Soc. B-Biol. Sci. 272, 1031–1038 (2005).

Bird, L. J. & Akhurst, R. J. Effects of host plant species on fitness costs of Bt resistance in Helicoverpa armigera (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Biol. Control 40, 196–203 (2007).

Blanco, C. A. et al. Plant Host Effect on the Development of Heliothis virescens F. (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Environ. Entomol. 37, 1538–1547 (2008).

Carriere, Y. et al. Effects of cotton cultivar on fitness costs associated with resistance of pink bollworm (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae) to Bt cotton. J. Econ. Entomol. 98, 947–954 (2005).

Kruger, M., Van Rensburg, J. B. J. & Van den Berg, J. No fitness costs associated with resistance of Busseola fusca (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) to genetically modified Bt maize. Crop Prot. 55, 1–6 (2014).

Petzold-Maxwell, J. L. et al. Effect of Maize Lines on Larval Fitness Costs of Cry1F Resistance in the European Corn Borer (Lepidoptera: Crambidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 107, 764–772 (2014).

Gustafson, D. I., Head, G. P. & Caprio, M. A. Modeling the impact of alternative hosts on Helicoverpa zea adaptation to Bollgard cotton. J. Econ. Entomol. 99, 2116–2124 (2006).

Jakka, S. R. K., Knight, V. R. & Jurat-Fuentes, J. L. Fitness Costs Associated With Field-Evolved Resistance to Bt Maize in Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 107, 342–351 (2014).

Xue, M., Pang, Y.-H., Wang, H.-T., Li, Q.-L. & Liu, T.-X. Effects of four host plants on biology and food utilization of the cutworm, Spodoptera litura. J. Insect Sci. 10, 1–14 (2010).

Sutherland, D. W. S. & Greene, G. L. In Suppression and management of cabbage looper populations (eds P. D. Lingren & G. L. Greene ) 1–13 (United States Department of Agriculture, 1984).

Janmaat, A. F. & Myers, J. Rapid evolution and the cost of resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis in greenhouse populations of cabbage loopers, Trichoplusia ni . P. Roy. Soc. B-Biol. Sci. 270, 2263–2270 (2003).

Wang, P. et al. Mechanism of resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis toxin Cry1Ac in a greenhouse population of the cabbage looper, Trichoplusia ni . Appl. Environ. Microb. 73, 1199–1207 (2007).

Song, X., Kain, W., Cassidy, D. & Wang, P. Resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis toxin Cry2Ab in Trichoplusia ni is conferred by a novel genetic mechanism. Appl. Environ. Microb. 81, 5184–5195 (2015).

Gahan, L. J., Pauchet, Y., Vogel, H. & Heckel, D. G. An ABC Transporter Mutation Is Correlated with Insect Resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis Cry1Ac Toxin. PLoS Genetics 6, e1001248 (2010).

Baxter, S. W. et al. Parallel Evolution of Bacillus thuringiensis Toxin Resistance in Lepidoptera. Genet. 189, 675–679 (2011).

Heckel, D. G. Learning the ABCs of Bt: ABC transporters and insect resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis provide clues to a crucial step in toxin mode of action. Pestic. Biochem. Phys. 104, 103–110 (2012).

Kain, W. et al. Resistance of Trichoplusia ni populations selected by Bacillus thuringiensis sprays to cotton plants expressing pyramided Bacillus thuringiensis toxins Cry1Ac and Cry2Ab. Appl. Environ. Microb. 81, 1884–1890 (2015).

Kain, W. C. et al. Inheritance of resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis Cry1Ac toxin in a greenhouse-derived strain of cabbage looper (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 97, 2073–2078 (2004).

Pardo-Lopez, L., Soberon, M. & Bravo, A. Bacillus thuringiensis insecticidal three-domain Cry toxins: mode of action, insect resistance and consequences for crop protection. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 37, 3–22 (2013).

Atsumi, S. et al. Single amino acid mutation in an ATP-binding cassette transporter gene causes resistance to Bt toxin Cry1Ab in the silkworm, Bombyx mori . P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, E1591–E1598 (2012).

Marchioro, C. A. & Foerster, L. A. Performance of the Wheat Armyworm, Pseudaletia sequax Franclemont, on Natural and Artificial Diets. Neotrop. Entomol. 41, 288–295 (2012).

Furstenberg-Hagg, J., Zagrobelny, M. & Bak, S. Plant Defense against Insect Herbivores. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 14, 10242–10297 (2013).

Oppert, B. Protease interactions with Bacillus thuringiensis insecticidal toxins. Arch. Insect Biochem. 42, 1–12 (1999).

Tiewsiri, K. & Wang, P. Differential alteration of two aminopeptidases N associated with resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis toxin Cry1Ac in cabbage looper. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 14037–14042 (2011).

Gryspeirt, A. & Gregoire, J. C. Effectiveness of the high dose/refuge strategy for managing pest resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) plants expressing one or two toxins. Toxins 4, 810–835 (2012).

Carriere, Y. et al. Sources, sinks, and the zone of influence of refuges for managing insect resistance to Bt crops. Ecol. Appl. 14, 1615–1623 (2004).

Shorey, H. H. Sex Pheromones of Noctuid Moths. II. Mating Behavior of Trichoplusia ni (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) with Special Reference to the Role of the Sex Pheromone. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 57, 371–377 (1964).

Thoming, G., Larsson, M. C., Hansson, B. S. & Anderson, P. Comparison of plant preference hierarchies of male and female moths and the impact of larval rearing hosts. Ecology 94, 1744–1752 (2013).

Cahenzli, F. & Erhardt, A. Transgenerational acclimatization in an herbivore - host plant relationship. P. Roy. Soc. B-Biol. Sci. 280, 20122856 (2013).

Jin, L. et al. Large-scale test of the natural refuge strategy for delaying insect resistance to transgenic Bt crops. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 169–174 (2015).

Butt, B. A. & Cantu, E. Sex determination of lepidopterous pupae. Vol. 33–75 (U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, 1962).

Carey, J. R. Applied Demography for Biologists with Special Emphasis on Insects. (Oxford University Press, 1993).

R Development Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. (2007) Available at: http://www.R-project.org.

Acknowledgements

We thank Wendy Kain for her excellent technical assistance and Jérôme Boissier for fruitful discussions on statistical analyses. This work was supported by the Biotechnology Risk Assessment Grant Program (competitive grant no. 2012-33522-19791) from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture and Agricultural Research Service, and the Cornell University Agricultural Experiment Station federal formula funds received from the USDA Cooperative State Research, Education, and Extension Service.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.W. and P.W. designed the experiments. R.W. performed the experiments. G.T. performed the statistical analyses. G.T. and P.W. analyzed the data. R.W., G.T. and P.W. wrote the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, R., Tetreau, G. & Wang, P. Effect of crop plants on fitness costs associated with resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis toxins Cry1Ac and Cry2Ab in cabbage loopers. Sci Rep 6, 20959 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep20959

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep20959

This article is cited by

-

Fitness costs associated with spinetoram resistance in Spodoptera frugiperda is driven by host plants

Journal of Pest Science (2023)

-

First documentation of major Vip3Aa resistance alleles in field populations of Helicoverpa zea (Boddie) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in Texas, USA

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

Transgenic cotton co-expressing chimeric Vip3AcAa and Cry1Ac confers effective protection against Cry1Ac-resistant cotton bollworm

Transgenic Research (2017)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.