Abstract

Enterococcus faecium is a commensal of the mammalian gastrointestinal tract, but is also found in non-enteric environments where it can grow between 10 °C and 45 °C. E. faecium has recently emerged as a multi-drug resistant nosocomial pathogen. We hypothesized that genes involved in the colonization and infection of mammals exhibit temperature-regulated expression control and we therefore performed a transcriptome analysis of the clinical isolate E. faecium E1162, during mid-exponential growth at 25 °C and 37 °C. One of the genes that exhibited differential expression between 25 °C and 37 °C, was predicted to encode a peptidoglycan-anchored surface protein. The N-terminal domain of this protein is unique to E. faecium and closely related enterococci, while the C-terminal domain is homologous to the Streptococcus agalactiae surface protein BibA. This region of the protein contains proline-rich repeats, leading us to name the protein PrpA for proline-rich protein A. We found that PrpA is a surface-exposed protein which is most abundant during exponential growth at 37 °C in E. faecium E1162. The heterologously expressed and purified N-terminal domain of PrpA was able to bind to the extracellular matrix proteins fibrinogen and fibronectin. In addition, the N-terminal domain of PrpA interacted with both non-activated and activated platelets.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Enterococci are Gram-positive, facultative anaerobic bacteria that are ubiquitously present in nature and which can grow in a wide range of temperatures between 10 °C and 45 °C1. The genus Enterococcus comprises around forty different species, including Enterococcus faecium and Enterococcus faecalis2. These two species are common commensals of the mammalian gastrointestinal tract, but in the last decades they have become important causes of nosocomial infections, ranging from urinary tract infections to infective endocarditis3.

In the late 1970s, E. faecalis was responsible for almost 95% of the Enterococcus-associated infections, with E. faecium being a comparatively rare cause of disease. In the last three decades this pattern has shifted and now E. faecium is becoming an increasingly frequent cause of hospital-associated infections4,5. Furthermore, the infections caused by E. faecium are often more difficult to treat than those caused by E. faecalis. This is due to the antibiotic resistance determinants that have recently accumulated in nosocomial E. faecium strains and which confer resistance to clinically important antibiotics, including β-lactams and vancomycin6.

E. faecium hospital-acquired bloodstream infections are often associated with the use of invasive medical devices such as catheters and implants, which disrupt the continuity of the epithelium. Notably, patients with a bacteremia caused by E. faecium have a worse prognosis than patients with bacteremias caused by other enterococci7,8. Bacterial surface-exposed proteins which can potentially interact with exposed host tissues, for instance due to the use of indwelling medical devices, have been studied in E. faecium to clarify the interactions of the bacterial cell with its host9. Several E. faecium surface proteins that are anchored to the peptidoglycan through a motif composed of leucine-proline-X-threonine/serine/alanine-glycine10,11, have been identified and characterized. These include pili12,13, surface proteins involved in biofilm formation14,15 and proteins that recognize the components of the extracellular matrix (ECM)10, including microbial surface components recognizing adhesive matrix molecules (MSCRAMMs)16,17.

Platelets, which are normally responsible for maintaining the balance in blood between fluidity and coagulation18, can contribute to binding of bacteria to host tissues which promote disease19. Gram-positive bacteria can attach to platelets either through direct binding of bacterial surface proteins to platelets20,21,22 or by indirect interactions mediated through plasma molecules like fibrinogen and fibronectin23. Fibrinogen and fibronectin are not only essential in the coagulation cascade for the clotting of blood, but can also be found as constituents of the host ECM24,25. In enterococci, several proteins have previously been described to interact with fibrinogen and fibronectin26,27,28, but only the Ebp-type pilus of E. faecalis has been shown to have a role in adherence to platelets29.

In this study we aimed to identify and characterize novel E. faecium proteins that may contribute to host-cell interactions. In order to successfully establish colonization or an infection, commensal and pathogenic bacteria need to adapt to the conditions that prevail in the host. Temperature is an important environmental signal that is frequently linked to the differential expression of bacterial virulence genes30,31. Consequently, we first performed comparative transcriptome profiling of E. faecium growing at 25 °C and 37 °C, to identify genes that exhibited higher expression at mammalian temperatures. We subsequently focused on a gene, encoding a surface protein (termed PrpA), that exhibited higher expression at 37 °C than at 25 °C. PrpA was further characterized in terms of its capacity to bind to ECM components and platelets.

Results

Thermo-regulated expression of a gene encoding a previously uncharacterized E. faecium surface protein

To identify E. faecium genes which exhibit thermo-regulated gene expression and consequently may have a role in virulence or colonization, we performed a transcriptome analysis of E. faecium E1162 during mid-exponential growth at 25 °C and 37 °C. In the transcriptome analysis, the differences in gene expression observed between 25 °C and 37 °C were relatively limited, reflecting the homeostatic nature of enterococcal physiology under permissive growth conditions. Nevertheless, thirty-three genes showed significantly higher expression at 37 °C compared to 25 °C. Supplementary Table 1 shows the genes that were up-regulated at 37 °C. The transcriptome analysis results were confirmed by qPCRs, in which we measured the expression of the four genes that exhibited the largest fold-difference in their expression at 37 °C versus 25 °C, as determined by the microarray analysis (Fig. 1). One of the genes that were differentially regulated during growth at 37 °C (4.4-fold, compared to growth at 25 °C), is predicted to encode a surface protein (locus-tag: EfmE1162_0376). The up-regulated expression of EfmE1162_0376 at 37 °C, combined with the observation that surface-exposed proteins frequently have a role in host-bacterial cell interactions in enterococci and other Gram-positives11,32, led us to further study the function of EfmE1162_0376.

Differences in relative gene expression of E. faecium E1162 between 25 °C and 37 °C.

Expression levels of four genes exhibiting higher expression (in the transcriptome analysis) during mid-exponential growth at 37 °C compared to 25 °C were determined by qRT-PCR. The data from the qRT-PCR were normalized using tufA as housekeeping gene. The differences in gene expression between 37 °C and 25 °C are shown. Error bars correspond to the standard deviation of four biological replicates.

After PCR amplification, cloning and sequencing of EfmE1162_0376 from E. faecium E1162 in an overexpression construct (see below), we noticed that the sequence that was originally deposited to Genbank for E. faecium E1162 (accession number: EFF35774) was inaccurate as one of the repeats in EfmE1162_0376 was lacking. Presumably, DNA repeats in the coding sequence of EfmE1162_0376 could not be correctly resolved using the pyrosequencing technology that was previously used to sequence the E. faecium E1162 genome33. The corrected sequence of EfmE1162_0376 has been deposited to Genbank (accession number: KF475784). EfmE1162_0376 (which was previously designated orf884 by Hendrickx et al.34) is present ubiquitously in E. faecium strains from different environments, including bloodstream infections and feces of hospitalized patients, healthy individuals and farm animals34.

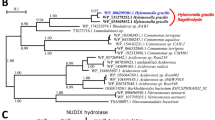

The genes that flank EfmE1162_0376 are transcribed in opposite directions, suggesting that EfmE1162_0376 is transcribed monocistronically (Fig. 2A). An overview of the protein encoded by EfmE1162_0376 is provided in Fig. 2B. The N-terminal domain of the protein encoded by EfmE1162_0376 contains a signal sequence, which is predicted to be required for the targeting of the protein to the cell wall. Based on currently available genome sequences, orthologous domains of the N-terminal region of this protein only exist in E. faecium and closely related species, like E. hirae, E. mundtii and E. durans, but not in E. faecalis or other bacteria. The C-terminal part of EfmE1162_0376 contains a predicted LPxTG-type anchor (LPKSG), which is expected to be required for the cell-wall anchoring of the protein to peptidoglycan by sortases32. Furthermore, the C-terminal part contains repeat regions that are rich in proline, aspartic acid and glutamic acid residues. The high number of proline residues (41 of 370 amino acids in the surface-anchored protein) present in the protein led us to name the protein PrpA, for proline-rich protein A. The C-terminal region of PrpA is similar (35% amino acid identity) to the C-terminal repeat motif of BibA, an adhesin of Streptococcus agalactiae35. Like in BibA, the proline-rich repeats of PrpA might serve to protrude the N-terminal domain to the outside.

The genetic context of prpA and overview of the PrpA protein.

Panel A shows the genetic environment of the prpA gene (in red). Arrows indicate the direction of transcription. The amino acid sequence of the PrpA protein is shown in Panel B. The N-terminal signal sequence is underlined and the LPxSG-motif is boxed. The position of the overexpressed and purified PrpA27-167 protein fragment is indicated in bold. The region of the protein that is highlighted in yellow is homologous to BibA of S. agalactiae (further details in the text) and repeats in this region are in italics. Proline residues in PrpA are indicated in orange.

The N-terminal domain of surface exposed proteins is of primary importance for their function in enterococci36,37 and other gram positive bacteria38. Therefore, we decided to focus on the role of the of the previously uncharacterized N-terminal domain of PrpA and its ability to interact with host components.

Determination of the transcriptional start site of prpA

In order to better understand the mechanism of the thermo-regulation of prpA expression, we performed 5’ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (5′ RACE) to map the 5′-end of prpA and to identify the promoter region of prpA. Upon gel electrophoresis of the 5′ RACE reactions, a band was observed at approximately 520 bp in the reaction that was performed with RNA isolated at 37 °C (Fig. 3A). The 5′ RACE reaction performed on RNA isolated during mid-exponential growth at 25 °C was considerably weaker, perhaps reflecting the lower expression of prpA at this temperature. Cloning and sequencing of the product revealed the transcriptional start site of prpA (Fig. 3B). Upstream of the prpA promoter, we identified two inverted repeats that may play a role in the transcriptional regulation of prpA.

Mapping of the transcriptional start site of prpA by 5′ RACE.

(A) Agarose gel electrophoresis of 5′ RACE PCRs shows the product at approximately 520 bp obtained during 5′RACE after nested amplification of cDNA (reverse transcribed from RNA isolated at 25 °C and 37 °C). (B) The upstream region of the prpA gene is shown. The transcriptional start site determined by 5′ RACE is indicated in bold. The boxes indicate the inverted repeats that are discussed in the text. Putative −35 and −10 promoter regions are underlined. The ATG start codon of prpA is shown in italics.

PrpA is a surface protein that is most abundant during exponential growth at 37 °C

In order to further characterize the function of the N-terminal fragment of PrpA, we heterologously overexpressed and purified PrpA27–167, corresponding to the N-terminal domain of PrpA, minus the signal sequence. We also constructed a markerless prpA mutant (ΔprpA) and a strain in which the mutation was complemented in trans (ΔprpA + prpA). No growth defect was observed in the mutant and complemented strain compared to the E1162 wild-type (Fig. S1A and S1B) when grown at 25 °C and 37 °C. Subsequently, we quantified surface-exposed levels of PrpA in exponential, stationary phase and overnight cultures of E1162 at 37 °C by flow cytometry, using polyclonal anti-PrpA antibodies. Levels of surface-exposed PrpA were highest in E1162 during early stages of exponential growth, when cells were harvested at A660 = 0.3 during growth at 37 °C. Quantities of surface-exposed PrpA declined at later stages of growth (Fig. 4A). Additionally, we measured the production of PrpA in E1162, ΔprpA and ΔprpA + prpA at 25 °C and 37 °C. Since we observed the highest levels of surface-exposed PrpA in E1162 at A660 = 0.3, we chose this condition for our subsequent experiments. In Fig. 3B we show that cells of E1162 grown at 25 °C had significantly lower levels of PrpA at the surface than cells grown at 37 °C, indicating that the lower expression of prpA at 25 °C observed in the transcriptome analysis translates to lower levels of surface-associated PrpA protein. As expected, in ΔprpA no signal was detected on the surface of cells. PrpA production is restored in the complemented strain, but also in this strain, levels of PrpA are higher at 37 °C than at 25 °C. Subsequently, we used transmission electron microscopy (TEM), to visualize the surface localization of PrpA in E. faecium, using polyclonal anti-PrpA antibodies and a protein A-10 nm gold particle conjugate (Fig. 5A,D). TEM showed that PrpA localized to the ‘old’ hemispheres of dividing cells of E1162 (Fig. 5B) and of ΔprpA + prpA (Fig. 5D). No apparent change in cellular morphology due to either the deletion or the overexpression of prpA was observed.

Analysis of surface-exposed PrpA levels.

PrpA was detected on the surface of the bacterium by flow cytometry using rabbit anti-PrpA IgG and FITC-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG. Panel A shows PrpA-levels on the surface of wild-type E. faecium E1162 grown at 37 °C. Samples were taken throughout exponential phase (A660 0.3, A660 0.5), transition phase (A660 0.7) and early stationary phase (A660 1.0). Levels of surface-exposed PrpA in an overnight culture of E1162 and during mid-exponential growth of ∆prpA are also shown. Panel B shows levels of surface-exposed PrpA in E. faecium E1162, ∆prpA and ∆prpA + prpA at 25 °C and 37 °C during mid-exponential growth (A660 0.3). The data presented were obtained in three independent experiments and significant differences (p < 0.01, Student’s t-test) are indicated by three asterisks. The geometrical mean of the fluorescence detected in the FITC channel is shown on the y-axis in both panels.

Cellular localization of PrpA assessed by transmission electron microscopy.

E. faecium E1162, ∆prpA and ∆prpA + prpA were grown at 37 °C to A660 0.3. Panel A shows cells incubated with pre-immune serum (negative control). Figure B to D show the localization of PrpA in the wild type, ∆prpA and complemented strain, respectively. PrpA was detected using rabbit anti-PrpA IgG and a subsequent incubation with 10 nm protein A-gold beads. The scale bar corresponds to 200 nm.

Thermo-regulation of PrpA is observed in other E. faecium strains

After characterizing the temperature-dependent production of PrpA in strain E1162, we studied the production of PrpA in fourteen E. faecium strains, of which the genomes were previously sequenced and which together covered the different phylogenetic clades of E. faecium, i.e. clade A1 representing clinical isolates, clade A2 representing animal strains and clade B representing human commensals39. All tested strains contained a copy of the prpA gene that was ≥79% identical to prpA in E. faecium E1162, with the difference mainly being introduced through the variable number of proline-rich repeats. We found that none of the clade B strains produced PrpA during mid-exponential growth (A660 = 0.3) at 25 °C or at 37 °C (Fig. 6). Besides E1162 (a clade A1 strain), we found that one additional strain from clade A1 and three strains from clade A2, were able to produce PrpA when grown at 37 °C. Interestingly, in all these strains the production of PrpA was found to be thermo-regulated, with higher levels at 37 °C, as observed before for E1162, when compared with 25 °C (Fig. 6). In the strains (n = 10) in which we were not able to demonstrate production of PrpA at the cell surface, sequence analysis of the prpA gene revealed that four strains (E2560, E1575, E2620 and E1007) contained mutations in prpA that led to a truncation of the gene.

Production of PrpA in E. faecium strains.

Production of PrpA is shown in fifteen different E. faecium strains isolated from diverse environments and belonging to different clades of the E. faecium species. Bacteria were grown to mid-exponential phase at either 25 °C or 37 °C and PrpA production was determined by flow cytometry. White and black bars indicate the production of PrpA at 25 °C and 37 °C, respectively. The horizontal line indicates the signal obtained from ∆prpA, where no PrpA is produced. Error bars indicate the standard deviation of the results in three independent experiments.

Alignment of the prpA promoter regions of the clade A strains did not provide evidence to why E1644, E1731 and E1636, which contain an intact copy of prpA, failed to produce this protein. The promoter sites, including the inverted repeat upstream of prpA promoter in E. faecium E1162, were completely identical to all of these three strains. In contrast to clade A strains, the same region in clade B strains contained several SNPs, which may affect the transcriptional regulation of the prpA gene in the clade B strains (Fig. S2).

PrpA27-167 binds to fibrinogen and fibronectin

In Gram-positive bacteria, surface-exposed proteins can mediate adherence to host tissues, often involving interactions with ECM components40,41,42. Therefore we studied whether PrpA could have a role in the adhesion to ECM proteins. Using ELISA, we found that PrpA27-167 binds to immobilized fibrinogen and fibronectin (Fig. 7A). Binding of PrpA27-167 to collagen types I, II and IV was also observed but at approximately three-fold lower levels compared to binding to fibrinogen and fibronectin. By ligand affinity blotting, we confirmed that PrpA27-167 binds to fibrinogen and fibronectin (Fig. 7B), but binding to collagen I could not be demonstrated (Fig. 7B) and identical, negative results were observed for collagen II and collagen IV (data not shown). Based on these data, we conclude that, among the tested ECM proteins, the N-terminal domain of PrpA only mediates binding to fibrinogen and fibronectin.

Binding of PrpA to ECMs proteins.

Panel A shows the binding of PrpA27-167 to immobilized extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins fibrinogen (Fg), fibronectin (Fn) and collagen type I (C I), II (C II) and IV (C IV) as determined by ELISA. These data are averages of two independent experiments performed with two technical replicates each. Panel B shows ligand-affinity blots of the binding of PrpA27-167 to ECMs proteins transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Binding of PrpA27-167 to ECMs proteins was detected using anti-PrpA IgG and HRP-goat anti-rabbit IgG. ECM proteins were also visualized after SDS – PAGE by staining with Coomassie. The different subunits of fibrinogen, collagen I and marker sizes (in kDa) are indicated.

Binding of E. faecium E1162 and ΔprpA to fibrinogen and fibronectin was also assessed by ELISA. E1162 was able to bind both fibrinogen and fibronectin however no significant difference between wild-type and mutant was found (data not shown), which could be due to the functional redundancy of multiple fibrinogen binding proteins in E. faecium43.

PrpA27-167 binds to human platelets

Apart from acting as extracellular matrix components, fibrinogen and fibronectin are also found in soluble forms in blood where they play an important role in the coagulation cascade25. Since the N-terminal domain of PrpA was found to mediate binding to fibrinogen, we examined the possibility whether PrpA27-167 could interact with platelets. The binding of FITC-labeled PrpA27-167 to resting platelets and platelets that were activated using the thrombin receptor-activating peptide TRAP, was assayed by flow cytometry. These experiments were performed with washed platelets, thereby minimizing the amount of fibrinogen in the assay and with resting and activated platelets in whole blood (RP-WP and AP-WB, respectively). Levels of surface-bound fibrinogen in each condition are shown in Fig. S3A for washed platelets and in Fig. S3B for platelets in whole blood. Activation of the washed platelets (Fig. S3C) and platelets in whole blood (Fig. S3D) was measured by the detection of the activation marker P-selectin on the surface of the platelets. PrpA27-167 was able to bind to RP (Fig. 8A) and to RP-WB (Fig. 8B), but activation of platelets considerably increased binding of PrpA27-167 to platelets, resulting in 3.0-fold higher binding to AP and 10.8-fold to AP-WB, compared to resting platelets in both conditions (Fig. 8A,B).

Binding of PrpA27-167 to platelets.

Binding of the protein to platelets was measured by flow cytometry. PrpA27-167 was labeled with FITC. Binding of PrpA27-167 to resting (RP) and TRAP-activated washed platelets (AP) is shown in panel A and to resting (RP-WB) and TRAP-activated platelets (AP-WB) in whole blood in panel B. In panels A and B, D-arginyl-glycyl-L-aspartyl-L-tryptophane (RGD) was used to block the fibrinogen receptor (GPIIb-IIIa αIIbβ3) in resting (RP + RGD) and activated (AP + RGD) washed platelets and in resting (RP-WB + RGD) and activated platelets (AP-WB + RGD) in whole blood. The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) is shown. The figures represent data from three independent experiments and the error bars indicate the standard deviation. Data were analyzed by Student’s t-test and significant differences are indicated by one (p < 0.05) or two (p < 0.01) asterisks.

The increased binding of PrpA27-167 to activated platelets could be due to the increase in surface area of platelets upon activation44,45. Alternatively, binding of PrpA27-167 to activated platelets may be mediated by the release and subsequent binding of fibrinogen to the platelet surface during activation, which would reflect the ability of PrpA to bind this ECM protein. Blocking the fibrinogen receptor α(IIb)β3 on the platelet surface using D-arginyl-glycyl-L-aspartyl-L-tryptophane (RGD)46, did not affect binding of PrpA27-167 to RP or RP-WB. Blocking the fibrinogen receptor upon platelet activation (AP + RGD and AP-WB + RGD) decreased, but did not abolish, binding of PrpA27-167 to platelets (Fig. 8A,B). In AP + RGD, no fibrinogen was detected on the platelet surface (Fig. S3A), but binding of PrpA27-167 to the platelet surface was still observed. These observations suggest that both direct and fibrinogen-mediated interactions of PrpA27-167 contribute to binding of this protein to platelets.

The ability of E. faecium E1162 cells and the prpA deletion mutant to bind to platelets was also assayed. Both E1162 and the prpA deletion mutant were able to bind to platelets but no differences were observed (data not shown). This result probably reflects redundancy of multiple platelet-binding proteins that are important for the interaction of E. faecium with platelets, as previously described for E. faecalis29,47,48.

Discussion

E. faecium is a commensal of the gastrointestinal tract but due to the accumulation of antibiotic resistance determinants and other adaptive elements, it has become an important nosocomial pathogen3,5,39,49. For opportunistic pathogens like E. faecium, which live in a wide variety of ecological niches ranging from plants and insects to the gastrointestinal tract of mammals, temperature is a particularly important environmental cue1,30,50. Under these different conditions, E. faecium needs to adjust its gene expression to survive in the environment and to be successful when interacting with the host31. Surface-exposed proteins in enterococci can facilitate bacterial interactions with host factors9, that might become exposed due to the use of indwelling medical devices in hospitalized patients. In the present study, we describe a thermo-regulated surface-exposed protein in E. faecium, termed PrpA, of which the N-terminal domain interacts with ECM components.

The presence of the C-terminal LPKSG motif in PrpA is predicted to allow anchoring of this protein to peptidoglycan. We hypothesized that in its peptidoglycan-anchored form, the proline-rich repeat region of PrpA may adopt a poly-proline helix-like conformation, similar to surface proteins with proline-rich repeat regions of streptococci35,51, thereby extending the functional N-terminal domain to the exterior milieu. For this reason, we focused on the function of the N-terminal domain of PrpA. However, the exact contribution of the C-terminal domain still needs to be investigated.

In accordance with the prediction that PrpA is a surface protein, we were able to detect surface-exposed PrpA on E. faecium E1162 cells, at higher levels when cultured at 37 °C than at 25 °C. E. faecium strains originating from healthy individuals that were previously assigned to clade B39, did not produce PrpA under the conditions tested. On the other hand, strains from clade A39, which covers strains of clinical and animal origins, can produce PrpA in a thermo-regulated fashion. Strains from E. faecium clade A are genetically distinct from the human commensal clade B strains and have been following distinct evolutionary trajectories39. In clade B strains, the role of PrpA remains to be determined and the expression of prpA may be regulated by environmental triggers other than temperature.

Using ELISA and ligand affinity blotting, we showed that the N-terminal domain of PrpA (PrpA27-167) binds to fibrinogen and fibronectin. We also observed that PrpA27-167 is able to interact with activated and resting platelets. Upon activation, fibrinogen bound to the platelet surface seems to facilitate the interaction of PrpA27-167 with the platelets, congruent with the ECM-binding characteristic of this protein. However, the binding of PrpA27-167 to activated washed platelets upon treatment with RGD, blocking the fibrinogen receptor, suggests that PrpA27-167 can also bind directly to platelets, in a fibrinogen-independent manner as has previously been described for other bacterial proteins29,47,48. The observation that deletion of prpA does not impair binding of E. faecium E1162 to fibrinogen, fibronectin and platelets, could reflect the functional redundancy of surface-exposed proteins of E. faecium in binding ECM components15,27,28.

Surface proteins of E. faecium are studied to understand the roles these proteins play in mediating interactions between the bacterial cell and its environment. PrpA is a surface protein that is characteristic for E. faecium and closely related enterococci, as it contains a unique N-terminal domain. In this study, we show that the N-terminal domain of PrpA interacts with fibrinogen, fibronectin and platelets. The thermo-regulated production of PrpA by clinical E. faecium isolation suggests that this protein may have a specific, but as yet undetermined, role in the colonization and infection of mammals.

Methods

Bacterial isolates, construction of a markerless prpA deletion mutant and in trans complementation

Information on the strains and plasmids that were used in this study is provided in Table S2. E. faecium was grown in Brain Heart Infusion (BHI; Oxoid, Basingstoke, United Kingdom) broth, unless otherwise noted. Escherichia coli was grown in Luria-Bertani Broth (LB; Oxoid). When needed, appropriate antibiotics were used at the following concentrations: gentamicin 300 μg ml−1 for E. faecium and 25 μg ml−1 for E. coli, spectinomycin 300 μg ml−1 for E. faecium and 100 μg ml−1 for E. coli and erythromycin 25 μg ml−1 for E. faecium and 150 μg ml−1 for E. coli. All antibiotics were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Saint Louis, MO, USA).

To generate a markerless prpA deletion mutant in E. faecium E1162, we used a previously described technique52. In brief, the 5′ and 3′ flanking regions (approximately 500 bp each) of the prpA gene were PCR amplified with two sets of primers: Up-PrpA-F-XhoI and Up-PrpA-R- EcoRI at the 5′ end and down-PrpA-F- EcoRI and down-PrpA-R-SmaI at the 3′ end of prpA (primer sequences are listed in Table S3). The two flanking regions were then fused together by PCR and cloned into pWS353. A gentamicin-resistance cassette flanked by lox66 and lox71 sites was PCR amplified (oligonucleotides listed in Table S3) and cloned into the EcoRI site that was generated between the 5′ and 3′ flanking regions of prpA in the pWS3 construct as described previously52. Finally, the construct, named pMP1, was electrotransformed into E. faecium E1162 and a markerless deletion of prpA (termed ΔprpA) was generated as described before52.

For in trans complementation of ΔprpA, prpA with its native promoter was amplified by PCR using Accuprime High Fidelity Taq Polymerase (Life Technologies, Bleiswijk, The Netherlands) with primers Comp-prpA-F-BamHI and Comp-prpA-R-PstI, which introduced BamHI and PstI restriction sites. The resulting product was cloned into pMSP353554. The construct was sequenced to confirm the absence of mutations in prpA. This plasmid was electrotransformed into ΔprpA as described previously52, generating the complemented strain ΔprpA + prpA. The expression of prpA in ΔprpA + prpA is under the control of its native promoter, as the inducible promoter on pMSP3535 is not activated by the addition of nisin in these experiments.

Determination of growth curves

E. faecium E1162, its isogenic ΔprpA mutant, the in trans complemented ΔprpA + prpA strain and E1162 carrying the vector pMSP353554, which was used for complementation, were grown overnight at 37 °C and 25 °C in BHI containing appropriate antibiotics. Cultures were diluted 1:50 in pre-warmed BHI at the appropriate temperature and the A660 was recorded for every 30 min until stationary phase was reached. Each experiment was performed in triplicate.

Transcriptome analysis of E. faecium E1162

To determine thermo-regulated gene expression, RNA was isolated from E. faecium E1162 grown in BHI until the mid-exponential growth phase (A660 = 0.3) at 25 °C and 37 °C in a shaking (200 rpm) water bath. Further details of growth conditions, RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis and labeling, microarray hybridization and data analysis have been described previously52.

Microarray data have been deposited in ArrayExpress (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/arrayexpress) under accession number E-MEXP-3941.

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis of prpA expression

Total RNA was isolated as described before and used to confirm the transcriptome analysis by qRT-PCR55. cDNA was synthesized using the Superscript III First-Strand Synthesis System (Life Technologies, Breda, The Netherlands) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Using synthesized cDNAs, qRT-PCR was performed using the Maxima SYBR Green/ROX qPCR Master Mix (Thermo Scientific, Breda, The Netherlands) and a StepOnePlus instrument (Life Technologies). The expression of tufA was used as a housekeeping control. Ct values were calculated using the StepOne analysis software v2.2. REST 2009 V2.0.13 (Qiagen, Venlo, The Netherlands) was used to determine the transcript levels, relative to tufA, of the assayed genes and for statistical analysis. We also performed qPCRs on reaction mixtures that lacked reverse transcriptase. In these negative control samples Ct values were consistently higher (>34) than in the samples in which reverse transcriptase was added (Ct values ranging between 15 and 26), indicating that residual or contaminant DNA was present at minimal quantities and did not influence the determination of gene expression levels by qPCR. This experiment was performed with four biological replicates.

Determination of the 5′ end of the prpA transcript

We used 5′RACE (Life Technologies) to map the 5′-end of the prpA mRNA, following the manufacturer’s instructions using two prpA-specific primers (GSP1 and GSP2) (Table S3). The amplified product was cloned using the CloneJET PCR cloning kit (Thermo Scientific) and sequenced by Sanger sequencing.

Heterologous overexpression and purification of PrpA

A gene fragment of prpA, encoding the N-terminal domain of PrpA excluding the N-terminal signal sequence, was amplified with the primers PrpA-BamHI and PrpA27-167-R-NotI-STOP. The purified protein is referred to in this manuscript as PrpA27-167. The PCR products were digested with BamHI and NotI and then cloned into the similarly digested overexpression vector pEF11056, resulting in pMP2 which is an overexpression construct encoding the proteins with an N-terminal polyhistidine tag. The overexpression construct was transformed into E. coli BL21 (DE3) and further overexpression and purification of the recombinant proteins was performed as described previously56.

Production of anti-PrpA polyclonal antibodies

Polyclonal antibodies against PrpA were raised by Eurogentec (Belgium) according to their rabbit immunization protocol. From the rabbit serum, IgG was purified using a 1-ml HiTrap Protein G HP column (GE Healthcare, Zeist, The Netherlands) and dialyzed overnight in phosphate buffered saline (PBS; 138 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 140 mM Na2HPO4, 1.8 mM KH2PO4, adjusted to pH 7.4 with HCl).

Quantification of surface-exposed PrpA by flow cytometry

Levels of surface-exposed PrpA were determined by flow cytometry, essentially as described previously57 with some minor modifications. In brief, E. faecium strains were grown overnight in BHI at 37˚C and 25˚C. The cells were then diluted (1:50) in pre-warmed media and cultured further at the appropriate temperature. Samples of the cultures were taken during different time points of the growth curve (A660 = 0.3, 0.5, 0.7, 1.0) and pelleted by centrifugation at 6,500 g for 1 min. PrpA was detected using 1:100 anti-PrpA rabbit IgG and 1:50 FITC-labeled goat anti rabbit IgG (Sigma-Aldrich). Flow cytometry was performed using the FACS Calibur system (BD Biosciences, Breda, The Netherlands). The geometric mean fluorescence was used as a measure for cell surface-exposed PrpA. This experiment was performed with three biologically independent replicates and statistical analysis of the data was performed using a two-tailed Student’s t-test.

Sequence analysis of prpA in E. faecium strains

The prpA gene of different E. faecium strains was amplified by PCR and sequenced using the primers PrpA_Fw and PrpA_Rv (Table S3). Analysis of the sequences was performed using Serial Cloner version 2.6 and alignments were made using Clustal Omega (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo/). The sequences have been deposited in Genbank under the following accession numbers: KP030673 (E980), KP030674 (E1007), KP030675 (E1071), KP030676 (E1574), KP030677 (E1575), KP030678 (E1578), KP030679 (E1636), KP030680 (E1644), KP030681 (E1731), KP030682 (E1972), KP030683 (E2560), KP030684 (E2620), KP030685 (E3548), KP030686 (E7345).

Determination of PrpA localization by transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

The cellular localization of PrpA in E. faecium E1162 was determined by transmission EM with immunogold labeling as described previously58. Bacteria were grown to mid-exponential phase (A660 = 0.3) and PrpA was detected using purified anti-PrpA rabbit IgG labeled with 1:60 diluted Protein A-gold (10 nm). Microscopy was performed on a JEOL 1010 transmission electron microscope (JEOL Europe, Nieuw-Vennep, The Netherlands).

ELISAs to determine binding of PrpA to ECM components

ELISAs to determine binding of PrpA27-167 to ECM components were performed as previously described15. After coating with ECM proteins, 50 μl of a 25 μg/ml solution in PBS of PrpA27-167 was used in the binding experiment. All ECMs proteins were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Binding of PrpA to ECM proteins was detected by anti-PrpA IgG (1:1000) and peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG-horseradish peroxidase 1:10000 from Southern Biotech (Birmingham, AL; USA) and measuring absorbance at 450 nm.

Ligand affinity blotting

Ligand affinity blotting was carried out as described by Hendrickx et al.15. 1 μg of ECM protein was loaded per well onto a 7.5% SDS gel. PVDF membranes (Merck Millipore) were incubated with purified PrpA27-167 at a concentration of 1 nM.

FITC labeling of PrpA

FITC was dissolved at a concentration of 1 mg/ml in 1 M sodium carbonate buffer pH 9.6. A 2 mg/ml solution of PrpA27-167 was prepared in the same buffer and 500 μl of this solution was mixed with 55 μl of FITC solution. This mixture was incubated for 2 h at 4 °C in the dark. After labeling, the solution was desalted using Polyacrylamide Spin Desalting Columns (Thermo Scientific). FITC labeling of the protein was assessed by SDS-PAGE, running both labeled and unlabeled protein onto a 12% gel and imaging the gel under the GFP channel of an Image Quant LAS4000. FITC was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich.

Binding of PrpA27-167 to human platelets

Whole blood was collected from three healthy volunteers using vacuum blood collection system tubes containing 3.2% sodium citrate. Platelets were isolated and washed as previously described59. The protocol for blood collection was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University Medical Center Utrecht. Written informed consent was obtained from all donors in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki. For each donor, the mean platelet volume (MPV) was measured using the cell analyzer CELL-DYN 1800 (Abbott) in both whole blood and in washed platelets (WP) to exclude that activation of the platelets had occurred during isolation. Platelets were left at room temperature for at least 30 min to ensure a resting state before they were used in the experiments.

In a final volume of 200 μl, FITC-labeled PrpA27-167 (50 μg/ml) were mixed with 20 μl of either whole blood or washed platelets (adjusted to 200,000 platelets/μl). Whole blood and platelets were activated with 200 μM of the thrombin receptor-activating peptide SFLLRN (TRAP-6) from Bachem (Bubendorf, Switzerland). Platelet activation was monitored through binding of phycoerythrin-labelled mouse anti-human P-selectin antibodies (diluted 1:50; BD Biosciences) to the activation marker P-selectin on the platelet surface60. Binding of fibrinogen to platelets was detected using FITC labeled rabbit anti-human fibrinogen antibodies (Dako-Agilent Technologies, Heverlee, Belgium, diluted 1:50). The fibrinogen receptor (αIIbβ3) was blocked using 100 μM of D-arginyl-glycyl-L-aspartyl-L-tryptophane (RGD)46, synthesized at the Department of Membrane Enzymology, Faculty of Chemistry, Utrecht University (Utrecht, The Netherlands). All samples were incubated for 30 min at room temperature and then fixed in a 0.2% paraformaldehyde, 0.9% NaCl solution. Flow cytometric detection of the binding of PrpA27-167 to platelets was performed on a FACSCanto II system (BD Biosciences). Statistical analysis of the data was performed using a two-tailed Student’s t-test.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Guzmán Prieto, A. M. et al. The N-terminal domain of the thermo-regulated surface protein PrpA of Enterococcus faecium binds to fibrinogen, fibronectin and platelets. Sci. Rep. 5, 18255; doi: 10.1038/srep18255 (2015).

References

Byappanahalli, M. N., Nevers, M. B., Korajkic, A., Staley, Z. R. & Harwood, V. J. Enterococci in the environment. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 76, 685–706 (2012).

Lebreton, F., Willems, R. J. L. & Gilmore, M. S. In Enterococci: From Commensals to Leading Causes of Drug Resistant Infection (ed Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary) Ch. 1, (2014).

Gilmore, M. S., Lebreton, F. & van Schaik, W. Genomic transition of enterococci from gut commensals to leading causes of multidrug-resistant hospital infection in the antibiotic era. Curr Opin Microbiol 16, 10–16 (2013).

de Kraker, M. E. et al. The changing epidemiology of bacteraemias in Europe: trends from the European Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System. Clin Microbiol Infect 19 (2013).

Willems, R. J. & van Schaik, W. Transition of Enterococcus faecium from commensal organism to nosocomial pathogen. Future Microbiol 4, 1125–1135 (2009).

Arias, C. A. & Murray, B. E. The rise of the Enterococcus: beyond vancomycin resistance. Nat Rev Microbiol 10 (2012).

Chou, Y. Y. et al. Vancomycin-resistant enterococcal bacteremia: comparison of clinical features and outcome between Enterococcus faecium and Enterococcus faecalis. J Microbiol Immunol Infect 41, 124–129 (2008).

Hayakawa, K. et al. Comparison of the clinical characteristics and outcomes associated with vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis and vancomycin-resistant E. faecium bacteremia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56, 2452–2458 (2012).

Hendrickx, A. P., van Schaik, W. & Willems, R. J. The cell wall architecture of Enterococcus faecium: from resistance to pathogenesis. Future Microbiol 8, 993–1010 (2013).

Ton-That, H., Marraffini, L. A. & Schneewind, O. Protein sorting to the cell wall envelope of Gram-positive bacteria. Biochim Biophys Acta 1694, 269–278 (2004).

Hendrickx, A. P., Willems, R. J., Bonten, M. J. & van Schaik, W. LPxTG surface proteins of enterococci. Trends Microbiol 17, 423–430 (2009).

Kim, D. S. et al. The fms21 (pilA)-fms20 locus encoding one of four distinct pili of Enterococcus faecium is harboured on a large transferable plasmid associated with gut colonization and virulence. J Med Microbiol 59, 505–507 (2010).

Sillanpaa, J. et al. Characterization of the ebp(fm) pilus-encoding operon of Enterococcus faecium and its role in biofilm formation and virulence in a murine model of urinary tract infection. Virulence 1, 236–246 (2010).

Heikens, E., Bonten, M. J. & Willems, R. J. Enterococcal surface protein Esp is important for biofilm formation of Enterococcus faecium E1162. J Bacteriol 189, 8233–8240 (2007).

Hendrickx, A. P. et al. SgrA, a nidogen-binding LPXTG surface adhesin implicated in biofilm formation and EcbA, a collagen binding MSCRAMM, are two novel adhesins of hospital-acquired Enterococcus faecium. Infect Immun 77, 5097–5106 (2009).

Nallapareddy, S. R., Weinstock, G. M. & Murray, B. E. Clinical isolates of Enterococcus faecium exhibit strain-specific collagen binding mediated by Acm, a new member of the MSCRAMM family. Mol Microbiol 47, 1733–1747 (2003).

Sillanpaa, J. et al. Identification and phenotypic characterization of a second collagen adhesin, Scm and genome-based identification and analysis of 13 other predicted MSCRAMMs, including four distinct pilus loci, In Enterococcus faecium. Microbiology 154, 3199–3211 (2008).

Heemskerk, J. W., Bevers, E. M. & Lindhout, T. Platelet activation and blood coagulation. Thromb Haemost 88, 186–193 (2002).

Jung, C. J. et al. Platelets enhance biofilm formation and resistance of endocarditis-inducing streptococci on the injured heart valve. J Infect Dis 205, 1066–1075 (2012).

Plummer, C. et al. A serine-rich glycoprotein of Streptococcus sanguis mediates adhesion to platelets via GPIb. Br J Haematol 129, 101–109 (2005).

de Haas, C. J. et al. Staphylococcal superantigen-like 5 activates platelets and supports platelet adhesion under flow conditions, which involves glycoprotein Ibα and αIIbβ3 . J Thromb Haemost : JTH 7, 1867–1874 (2009).

Miajlovic, H. et al. Direct interaction of iron-regulated surface determinant IsdB of Staphylococcus aureus with the GPIIb/IIIa receptor on platelets. Microbiology 156, 920–928 (2010).

Fitzgerald, J. R. et al. Fibronectin-binding proteins of Staphylococcus aureus mediate activation of human platelets via fibrinogen and fibronectin bridges to integrin GPIIb/IIIa and IgG binding to the FcγRIIa receptor. Mol Microbiol 59, 212–230 (2006).

Cho, J. & Mosher, D. F. Role of fibronectin assembly in platelet thrombus formation. J Thromb Haemost 4, 1461–1469 (2006).

Mosesson, M. W. Fibrinogen and fibrin structure and functions. J Thromb Haemost 3, 1894–1904 (2005).

Sillanpaa, J. et al. A family of fibrinogen-binding MSCRAMMs from Enterococcus faecalis. Microbiology 155, 2390–2400 (2009).

Galloway-Pena, J. R. et al. The identification and functional characterization of WxL proteins from Enterococcus faecium reveal surface proteins involved in extracellular matrix interactions. J Bacteriol 197, 882–892 (2015).

Rozdzinski, E., Marre, R., Susa, M., Wirth, R. & Muscholl-Silberhorn, A. Aggregation substance-mediated adherence of Enterococcus faecalis to immobilized extracellular matrix proteins. Microb Pathog 30, 211–220 (2001).

Nallapareddy, S. R. et al. Conservation of Ebp-type pilus genes among Enterococci and demonstration of their role in adherence of Enterococcus faecalis to human platelets. Infect Immun 79, 2911–2920 (2011).

Konkel, M. E. & Tilly, K. Temperature-regulated expression of bacterial virulence genes. Microbes Infect 2, 157–166 (2000).

Steinmann, R. & Dersch, P. Thermosensing to adjust bacterial virulence in a fluctuating environment. Future microbiol 8, 85–105 (2013).

Navarre, W. W. & Schneewind, O. Surface proteins of gram-positive bacteria and mechanisms of their targeting to the cell wall envelope. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 63, 174–229 (1999).

van Schaik, W. et al. Pyrosequencing-based comparative genome analysis of the nosocomial pathogen Enterococcus faecium and identification of a large transferable pathogenicity island. BMC genomics 11, 239 (2010).

Hendrickx, A. P., van Wamel, W. J., Posthuma, G., Bonten, M. J. & Willems, R. J. Five genes encoding surface-exposed LPXTG proteins are enriched in hospital-adapted Enterococcus faecium clonal complex 17 isolates. J Bacteriol 189, 8321–8332 (2007).

Santi, I. et al. BibA: a novel immunogenic bacterial adhesin contributing to group B Streptococcus survival in human blood. Mol Microbiol 63, 754–767 (2007).

Nallapareddy, S. R., Sillanpaa, J., Ganesh, V. K., Hook, M. & Murray, B. E. Inhibition of Enterococcus faecium adherence to collagen by antibodies against high-affinity binding subdomains of Acm. Infect Immun 75, 3192–3196 (2007).

Tendolkar, P. M., Baghdayan, A. S. & Shankar, N. The N-terminal domain of enterococcal surface protein, Esp, is sufficient for Esp-mediated biofilm enhancement in Enterococcus faecalis. J Bacteriol 187, 6213–6222 (2005).

Zong, Y. et al. A ‘Collagen Hug’ model for Staphylococcus aureus CNA binding to collagen. EMBO J 24, 4224–4236 (2005).

Lebreton, F. et al. Emergence of epidemic multidrug-resistant Enterococcus faecium from animal and commensal strains. mBio 4, (2013).

Nallapareddy, S. R., Qin, X., Weinstock, G. M., Hook, M. & Murray, B. E. Enterococcus faecalis adhesin, ace, mediates attachment to extracellular matrix proteins collagen type IV and laminin as well as collagen type I. Infect Immun 68, 5218–5224 (2000).

Schwarz-Linek, U., Hook, M. & Potts, J. R. The molecular basis of fibronectin-mediated bacterial adherence to host cells. Mol Microbiol 52, 631–641 (2004).

Rivera, J., Vannakambadi, G., Hook, M. & Speziale, P. Fibrinogen-binding proteins of Gram-positive bacteria. Thromb Haemosts 98, 503–511 (2007).

Teng, F., Kawalec, M., Weinstock, G. M., Hryniewicz, W. & Murray, B. E. An Enterococcus faecium secreted antigen, SagA, exhibits broad-spectrum binding to extracellular matrix proteins and appears essential for E. faecium growth. Infect Immun 71, 5033–5041 (2003).

Frojmovic, M. M. & Milton, J. G. Human platelet size, shape and related functions in health and disease. Physiol Rev 62, 185–261 (1982).

Jennings, L. K. Mechanisms of platelet activation: need for new strategies to protect against platelet-mediated atherothrombosis. Thromb Haemost 102, 248–257 (2009).

Basani, R. B. et al. RGD-containing peptides inhibit fibrinogen binding to platelet αIIbβ3 by inducing an allosteric change in the amino-terminal portion of αIIb . J Biol Chem 276, 13975–13981 (2001).

Rasmussen, M., Johansson, D., Sobirk, S. K., Morgelin, M. & Shannon, O. Clinical isolates of Enterococcus faecalis aggregate human platelets. Microbes Infect 12, 295–301 (2010).

Maddox, S. M., Coburn, P. S., Shankar, N. & Conway, T. Transcriptional regulator PerA influences biofilm-associated, platelet binding and metabolic gene expression in Enterococcus faecalis. PLoS One 7, e34398 (2012).

Willems, R. J. et al. Global spread of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium from distinct nosocomial genetic complex. Emerg Infect Dis 11, 821–828 (2005).

Martin, J. D. & Mundt, J. O. Enterococci in insects. Appl Microbiol 24, 575–580 (1972).

Fischetti, V. A. Streptococcal M protein: molecular design and biological behavior. Clin Microbiol Rev 2, 285–314 (1989).

Zhang, X. et al. Genome-wide identification of ampicillin resistance determinants in Enterococcus faecium. PLoS Genet 8, e1002804 (2012).

Zhang, X., Vrijenhoek, J. E., Bonten, M. J., Willems, R. J. & van Schaik, W. A genetic element present on megaplasmids allows Enterococcus faecium to use raffinose as carbon source. Environ Microbiol 13, 518–528 (2011).

Bryan, E. M., Bae, T., Kleerebezem, M. & Dunny, G. M. Improved vectors for nisin-controlled expression in gram-positive bacteria. Plasmid 44, 183–190 (2000).

Zhang, X. et al. A LacI-family regulator activates maltodextrin metabolism of Enterococcus faecium. PLoS One 8, e72285 (2013).

Bardoel, B. W., van Kessel, K. P., van Strijp, J. A. & Milder, F. J. Inhibition of Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence: characterization of the AprA-AprI interface and species selectivity. J Mol Biol 415, 573–583 (2012).

Van Wamel, W. J. et al. Growth condition-dependent Esp expression by Enterococcus faecium affects initial adherence and biofilm formation. Infect Immun 75, 924–931 (2007).

Hendrickx, A. P. et al. Expression of two distinct types of pili by a hospital-acquired Enterococcus faecium isolate. Microbiology 154, 3212–3223 (2008).

Korporaal, S. J. et al. Platelet activation by oxidized low density lipoprotein is mediated by CD36 and scavenger receptor-A. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 27, 2476–2483 (2007).

Merten, M. & Thiagarajan, P. P-selectin expression on platelets determines size and stability of platelet aggregates. Circulation 102, 1931–1936 (2000).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the European Union Seventh Framework Programme (FP7-HEALTH-2011-single-stage) “Evolution and Transfer of Antibiotic Resistance” (EvoTAR) under grant agreement number 282004 and by an NWO-VENI grant (916.86.044) and NWO-VIDI grant (917.13.357) to W.v.S. The authors thank Mark Roest for critical discussions, Thijs C. van Holten and Valentina De Angelis for the training they provided for the isolation and handling of platelets, Claudia M.E. Schapendonk for her technical assistance in the transcriptome analyses and Wouter van Leeuwen for his technical support in the flow cytometry experiments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.v.S. designed the study. A.M.G.P., R.T.U., X.Z., D.B., A.K., M.v.L.A., J.P.O., M.P., F.L.P., D.W. and J.H. performed experiments. All authors contributed to data interpretation. The manuscript was written by A.M.G.P., A.P.A.H., M.J.M.B., R.J.L.W. and W.v.S.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Guzmán Prieto, A., Urbanus, R., Zhang, X. et al. The N-terminal domain of the thermo-regulated surface protein PrpA of Enterococcus faecium binds to fibrinogen, fibronectin and platelets. Sci Rep 5, 18255 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep18255

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep18255

This article is cited by

-

Gut microbiome alterations in patients with COVID-19-related coagulopathy

Annals of Hematology (2023)

-

The human blood parasite Schistosoma mansoni expresses extracellular tegumental calpains that cleave the blood clotting protein fibronectin

Scientific Reports (2017)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.