Abstract

The patched (PTCH) mutation rate in nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome (NBCCS) reported in various studies ranges from 40 to 80%. However, few studies have investigated the role of PTCH in clinical conditions suggesting an inherited predisposition to basal cell carcinoma (BCC), although it has been suggested that PTCH polymorphisms could predispose to multiple BCC (MBCC). In this study, we therefore performed an exhaustive analysis of PTCH (mutations detection and deletion analysis) in 17 patients with the full complement of criteria for NBCCS (14 sporadic and three familial cases), and in 48 patients suspected of having a genetic predisposition to BCC (MBCC and/or age at diagnosis ⩽40 years and/or familial BCC). Eleven new germline alterations of the PTCH gene were characterised in 12 out of 17 patients harbouring the full complement of criteria for the syndrome (70%). These were frameshift mutations in five patients, nonsense mutations in five patients, a small inframe deletion in one patient, and a large germline deletion in another patient. Only one missense mutation (G774R) was found, and this was in a patient affected with MBCC, but without any other NBCCS criterion. We therefore suggest that patients harbouring the full complement of NBCCS criteria should as a priority be screened for PTCH mutations by sequencing, followed by a deletion analysis if no mutation is detected. In other clinical situations that suggest genetic predisposition to BCC, germline mutations of PTCH are not common.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome (NBCCS, or Gorlin's syndrome) is an autosomal dominant syndrome predisposing to basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) and numerous developmental abnormalities (Gorlin, 2004). The prevalence is estimated at one per 57 000 (Evans et al, 1991); approximately 0.4% of all cases of BCC and 2% of BCC patients under 45 years of age are affected by NBCCS (Farndon et al, 1992).

NBCCS has been linked to germline mutations in the human homologue of the Drosophila segment polarity gene patched (PTCH) (Hahn et al, 1996; Johnson et al, 1996), and the rate of neomutation is high (Shanley et al, 1994). The PTCH mutation frequency in NBCCS patients reported varies considerably in the different studies, ranging from 40 to 80% (Kimonis et al, 2004; Marsh et al, 2005).

The PTCH gene consists of 23 exons, and encodes a 1447-amino-acid integral membrane protein, with 12 transmembrane regions, two extracellular loops, and a putative sterol-sensing domain. Most PTCH germline mutations are predicted to lead to premature truncation of the Ptc1 protein, and assumed to represent null PTCH alleles (Wicking and Bale, 1997), suggesting that many aspects of the phenotype apart from BCC result from haploinsufficiency. Tumours in NBCCS patients are likely to arise when the remaining PTCH allele is inactivated, which would be consistent with PTCH acting as a tumour suppressor gene (Gailani et al, 1992).

In addition, deletions of interstitial chromosome 9q have been identified in some NBCCS patients (Olivieri et al, 2003; Haniffa et al, 2004; Boonen et al, 2005).

One problem that arises is the possibility of a misdiagnosis of NBCCS, because of the complex phenotype of this syndrome. Various clinical and radiological criteria have been used to diagnose NBCCS; these are categorised as major and minor criteria. Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome is considered to be certain when at least two of the four major criteria are present (multiple BCC (MBCCs), palmar and plantar epidermal pits, jaw keratocysts, and cerebral calcification) (Shanley et al, 1994). Patients may also display many other clinical features that are classified as minor criteria (Table 1) (Lo Muzio et al, 1999).

In addition to NBCCS, recent publications suggest that allelic variation of PTCH could also influence susceptibility to BCC (Strange et al, 2004a, 2004b; Asplund et al, 2005). In particular, some PTCH haplotypes, including polymorphisms in exon 23 (c.3944C), intron 15 (G2560+9), or exon 12 (c.1686C), seem to have a potentially protective effect against BCC (Strange et al, 2004a, 2004b).

The goal of this study was to search for PTCH germline abnormalities both in patients harbouring all the criteria for NBCCS and in those clinically suspected of having a genetic predisposition towards BCC (MBCC and/or BCC while under 40 years of age and/or familial BCC).

Patients and methods

Selection of patients

This study was performed from 2003 to January 2005. Patients were enrolled at the Saint Louis (60%), Ambroise Paré (25%), Bichat-Claude Bernard (5%), Tarnier (5%), and Henri Mondor (5%) hospitals, all of which are located in or near the city of Paris (France). Sixty-five patients were prospectively enrolled in the study, 10% of whom were newly diagnosed cases. Two different categories of patients were studied:

-

1)

Patients affected by the typical NBCCS (17 index cases: three familial and 14 sporadic) who displayed at least two of the major criteria (MBCC, palmo-plantar pits, cerebral calcifications, odontogenic keratocysts) or one major criterion plus at least two minor criteria as defined by Shanley et al (1994). In addition, seven additional NBCCS patients from the three enrolled families were also studied.

-

2)

Patients strongly suspected of having a genetic predisposition towards BCC (48 cases), characterised by either (i) MBCCs (35 cases), defined as the presence of at least two BCCs in the same patient confirmed by pathology reports, and/or (ii) BCC in patients under 40 years of age (28 cases) and/or (iii) familial BCC (10 cases), defined as the presence of at least two BCC cases in first- or second-degree relatives (all cases confirmed by pathology reports). For familial BCC cases, only the proband was enrolled. To exclude the presence of NBCCS features in this ‘BCC-predisposed’ non-NBCCS group, a careful clinical exam was realised to search for BCC, pits on palm and soles, facial, ocular, and limbs abnormalities. In addition, dental and crane X-rays were also performed in order to verify the absence of odontogenic keratocysts and intracranial calcifications.

Written informed consent, agreeing to peripheral blood sampling and genetic analysis, was obtained from each patient enrolled in the study. Genomic DNA was isolated from peripheral blood leucocytes of all the participants by routine methods (Miller et al, 1988).

PTCH sequencing

The 23 exons of the PTCH coding sequence were amplified using 23 primer pairs (Table 2). PCR conditions included 35 denaturing cycles at 95°C for 30 s, annealing at 60°C for 30 s, elongation at 72°C for 45 s for exons 1 and 4; and 35 denaturing cycles at 96°C for 30 s, annealing at 63°C for 30 s, elongation at 72°C for 1 min for exons 5–23. Sequence analysis was performed on an ABI-Prism 3100 automated DNA sequencer using 10 ng PCR purified products and Big-Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing kits (Perkin Elmer, Courtaboeuf cedex, France), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The functionality of the nonsynonymous variant was predicted using the Polyphen and SIFT informatics program (http://tux.EMBL-Heidelberg.DE/ramensky/; http://blocks.fhcrc.org/sift/SIFT_seq_submit2.html).

PTCH deletion analysis

Real-time quantitative PCR

Real-time quantitative PCR was performed using SYBR Green I dye as a fluorescent signal. This dye binds specifically to the minor groove of double-stranded DNA, making it possible to detect PCR product formation (Ginzinger, 2002).

In order to examine both ends of PTCH, two targets were initially chosen on PTCH exons 1 and 23, and then, to extend the analysis, two other PTCH targets on exons 4 and 15, respectively, were also examined (Table 2). Two single-copy sequences were used as reference sequences: MYH9, mapping at 22q13.1, and Rb, mapping at 13q. Five microlitres of DNA was added to the PCR reaction mixture containing 1 × SYBR Green buffer (Applied Biosystems, Courtaboeuf cedex, France), 300 nM forward and reverse primers, 5 mM MgCl2 (3 mM for 8q11 SST), 200 μ M dNTP, and 0.6 U of AmpliTaq Gold (Applied Biosystems) in a final volume of 25 μl.

Each series of PCR reactions included two negative controls, containing water in place of DNA, and a five-point standard curve. The standard curve was plotted using serial dilutions of normal PBMC in Tris (10 mM)–EDTA (1 mM) buffer, ranging from 10 to 0.02 ng μl−1 (corresponding to 50–0.1 ng of DNA analysed per well). The same dilutions were used for all targets and reference sequences. PCR was performed on the ABI PRISM 7700 Sequence detector system (Applied Biosystems). All analyses were performed in duplicate. The PCR amplification profile was as follows: initial denaturing at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 denaturing cycles at 95°C for 10 s, and a combined annealing and extension step at 65°C for 1 min. Detection of the fluorescent product was carried out at the end of the extension period. To confirm amplification specificity, the PCR products from each primer pair were subjected to a melting curve analysis, and subsequent agarose gel electrophoresis. The concentration of each gene was calculated based on the appropriate calibration curve. Relative copy numbers of PTCH were then obtained by calculating the ratio of the result obtained for each target to the MYH9 and Rb value. The normalised ratio of each target on MYH9 and Rb was expected to be close to 1, if no deletion had occurred.

Microsatellite analysis

Two microsatellite markers were studied: (i) a CGG repeat localised in the 5′UTR, which was genotyped by sequencing PTCH exon 1, and (ii) a CA repeat localised in intron 2 (Aboulkassim et al, 2003), which was genotyped by migration of the fluorescent-labelled PCR product on a 310 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems).

Multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification

PTCH deletion was also investigated by multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA), a quantitative, multiplex PCR method, as described previously (Gille et al, 2002). Multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification was used to determine the relative copy number of each of the 23 PTCH exons, and was performed using an available commercial kit (SALSA MLPA KIT P067 PTCH, mrc-Holland).

Results

Seventeen patients were considered to have NBCCS, on the basis of the presence of two major criteria, or of one major criterion plus two or more minor criteria. Three were nonrelated familial cases, and 14 were sporadic cases. The three families had, respectively, four, three, and two NBCCS patients, all first-degree related. Thirteen patients had two or more major NBCCS criteria (four patients with two major criteria, seven patients with three major criteria, and two patients with all four criteria). Four NBCCS patients had only one major criterion plus two, four or five minor criteria. The frequencies of the major criteria were as follows: MBCC (88%), palmo-plantar pits (78%), odontogenic keratocysts (70%), and cerebral calcifications (57%). The most frequent ‘minor’ criteria were macrocephaly (70%), epidermal cysts (60%), scoliosis (60%), hypertelorism (50%), and strabism (36%). The median age at the first BCC in this NBCCS group was 27 years.

Forty-eight patients suspected of being predisposed to BCC were characterised by either (i) the occurrence of MBCC (35 cases) and/or (ii) the occurrence of BCC before the age of 40 years (28 cases), and/or (iii) the presence of familial BCC (10 cases), defined as the presence of at least two BCC cases in first- or second-degree relatives. The median age at the first BCC in this group was 42 years.

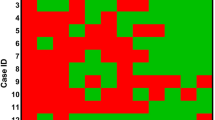

PTCH mutations were identified in 12 out of 17 patients harbouring the full complement of criteria for NBCCS. These were frameshift mutations in five patients, nonsense mutations in five patients, and one in frame deletion in one patient (see Table 3). An identical, nonsense mutation, W129X, was characterised in two unrelated patients. PTCH mutations were detected in all three familial cases, and were shown to segregate with the disease in the families, as they were detected in all the seven relatives affected by NBCCS (Table 3).

In addition, a large germline deletion was detected in another typical NBCCS patient. Quantitative PCR analysis showed that three of the four exons examined (4, 15, 23) were deleted, whereas the first exon was not. As the patient was heterozygous for a microsatellite localised in intron 2, this means that the deletion must begin after exon 2 of PTCH. These results were confirmed by MLPA, with a 50% reduction in signal intensity from exons 5 to 23, whereas exon 3 was normal. As the MLPA kit does not explore exon 4, both results are concordant and show the presence of a large PTCH deletion including exons 4–23. PTCH deletions were also looked for in the five remaining NBCCS patients who did not harbour any PTCH mutation, but none was found. To summarise, therefore, germline mutations or deletions of PTCH were present in 70% of NBCCS patients.

In contrast, in the BCC group without any other criterion for NBCCS, only one missense variant, G774R, was found in a patient affected with MBCC. This patient had five different BCCs, all localised in the head and neck region, the first BCC being diagnosed at the age of 46 years. This variant localised in the putative fourth extracellular domain, and is predicted to be damaging by the SNP prediction programs Polyphen and SIFT (http://tux.embl-heidelberg.de/ramensky/; http://blocks.fhcrc.org/sift/SIFT.html). No large deletions of PTCH were observed by real-time PCR or MLPA in the remaining patients with a suspected genetic predisposition to BCC.

Discussion

In this study, we identified PTCH mutations or deletions in 12 out of 17 patients with NBCCS (70%). As far as we know, only one study has been performed in the French population (Boutet et al, 2003). Of the 11 mutations identified in NBCCS patients, 10 resulted in truncation of the PTCH protein owing to frameshifts or nonsense mutations. This is consistent with the finding that most (86%) mutations lead to premature termination of the protein (Wicking et al, 1997; Fujii et al, 2003).

Previously, PTCH mutations have been found in 40–80% of NBCCS patients (Chidambaram et al, 1996; Wicking et al, 1997; Boutet et al, 2003). Although our group is quite small, the exhaustive screening for PTCH exons and flanking intronic regions by direct sequencing and deletion analysis may have increased the mutation detection rate.

We identified a large PTCH deletion in a patient harbouring the typical signs of NBCCS. In all, five patients that share NBCCS features were previously been reported to carry an interstitial chromosome 9q deletion identified by cytogenetic analysis (Shimkets et al, 1996; Sasaki et al, 2000; Haniffa et al, 2004; Midro et al, 2004). This indicates that large PTCH deletions are not a rare mechanism of PTCH inactivation, and this possibility should be investigated if no PTCH mutation is detected.

Despite the exhaustive analysis, no PTCH mutation or large deletion was found in five of the NBCCS patients. This is likely to be due to the existence of mutations outside the regions analysed possibly in introns or regulatory elements. An alternative hypothesis could be the presence of a somatic mosaicism, or the existence of mutations in another gene implicated in the sonic hedgehog pathway, as has been shown to occur in sporadic BCC (Reifenberger et al, 1998; Xie et al, 1998).

In the group of BCC patients without any other NBCCS criterion, only one missense mutation (G774R) was found in a patient with MBCC without any other NBCCS criteria (in particular, this patient had a normal head circumference, no facial or ocular abnormalities, and the chest and crane X-rays did not show any skeletal abnormality or intracranial calcification). Unfortunately, segregation could not be assessed because his parents were deceased. Therefore, the significance of this amino-acid substitution will not become completely clear until a functional analysis is performed. However, this could be a causative mutation, as (i) it is predicted to be damaging by two bioinformatic programs Polyphen and SIFT and (ii) it was not reported in any previous study or in the NCBI SNP database. On the other hand, we cannot exclude the possibility that this could be a rare polymorphism.

We did not found any other PTCH mutation in this group (P<0.0001), which indicates that when other NBCCS criteria are absent, PTCH mutations are rarely involved in predisposition to BCC. Nevertheless, it remains possible that PTCH polymorphisms located outside the coding sequence or intron–exon junctions could influence BCC susceptibility, as has been suggested by recent publications (Strange et al, 2004a, 2004b; Asplund et al, 2005).

In conclusion, germline abnormalities (mutations and deletions) of PTCH are very predominantly observed in patients with the full criteria for NBCCS. We therefore suggest that patients harbouring the full complement of NBCCS criteria should, as a priority, be screened for PTCH mutations by sequencing, followed by a deletion analysis if no mutation is detected. The finding of a PTCH mutation confirms the clinical diagnosis of NBCCS, therefore validating the clinical and radiological diagnostic criteria of this syndrome. The molecular confirmation of NBCCS diagnosis permits a better clinical monitoring (in particular, dermatological), a choice of the rational therapeutic (e.g. avoiding radiotherapy for treatment of BCCs). Moreover, it makes it possible to carry out a genetic council in the families concerned, and to offer the possibility of antenatal diagnosis if the families wish it.

Change history

16 November 2011

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Aboulkassim TO, LaRue H, Lemieux P, Rousseau F, Fradet Y (2003) Alteration of the PATCHED locus in superficial bladder cancer. Oncogene 22: 2967–2971

Asplund A, Gustafsson AC, Wikonkal NM, Sela A, Leffell DJ, Kidd K, Lundeberg J, Brash DE, Ponten F (2005) PTCH codon 1315 polymorphism and risk for nonmelanoma skin cancer. Br J Dermatol 152: 868–873

Boonen SE, Stahl D, Kreiborg S, Rosenberg T, Kalscheuer V, Larsen LA, Tommerup N, Brondum-Nielsen K, Tumer Z (2005) Delineation of an interstitial 9q22 deletion in basal cell nevus syndrome. Am J Med Genet A 132: 324–328

Boutet N, Bignon YJ, Drouin-Garraud V, Sarda P, Longy M, Lacombe D, Gorry P (2003) Spectrum of PTCH1 mutations in French patients with Gorlin syndrome. J Invest Dermatol 121: 478–481

Chidambaram A, Goldstein AM, Gailani MR, Gerrard B, Bale SJ, DiGiovanna JJ, Bale AE, Dean M (1996) Mutations in the human homologue of the Drosophila patched gene in Caucasian and African-American nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome patients. Cancer Res 56: 4599–4601

den Dunnen JT, Antonarakis SE (2001) Nomenclature for the description of human sequence variations. Hum Genet 109: 121–124

Evans DG, Farndon PA, Burnell LD, Gattamaneni HR, Birch JM (1991) The incidence of Gorlin syndrome in 173 consecutive cases of medulloblastoma. Br J Cancer 64: 959–961

Farndon PA, Del Mastro RG, Evans DGR, Kilpatrick MW (1992) Location of gene for Gorlin syndrome. Lancet 339: 581–582

Fujii K, Kohno Y, Sugita K, Nakamura M, Moroi Y, Urabe K, Furue M, Yamada M, Miyashita T (2003) Mutations in the human homologue of Drosophila patched in Japanese nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome patients. Hum Mutat 21: 451–452

Gailani MR, Bale SJ, Leffell DJ, DiGiovanna JJ, Peck GL, Poliak S, Drum MA, Pastakia B, McBride OW, Kase R, Greene M, Mulvihill JJ, Bale AE (1992) Developmental defects in Gorlin syndrome related to a putative tumor suppressor gene on chromosome 9. Cell 69: 111–117

Gille JJ, Hogervorst FB, Pals G, Wijnen JT, van Schooten RJ, Dommering CJ, Meijer GA, Craanen ME, Nederlof PM, de Jong D, McElgunn CJ, Schouten JP, Menko FH (2002) Genomic deletions of MSH2 and MLH1 in colorectal cancer families detected by a novel mutation detection approach. Br J Cancer 87: 892–897

Ginzinger DG (2002) Gene quantification using real-time quantitative PCR: an emerging technology hits the mainstream. Exp Hematol 30: 503–512

Gorlin RJ (2004) Nevoid basal cell carcinoma (Gorlin) syndrome. Genet Med 6: 530–539

Hahn H, Wicking C, Zaphiropoulous PG, Gailani MR, Shanley S, Chidambaram A, Vorechovsky I, Holmberg E, Unden AB, Gillies S, Negus K, Smyth I, Pressman C, Leffell DJ, Gerrard B, Goldstein AM, Dean M, Toftgard R, Chenevix-Trench G, Wainwright B, Bale AE (1996) Mutations of the human homolog of Drosophila patched in the nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome. Cell 85: 841–851

Haniffa MA, Leech SN, Lynch SA, Simpson NB (2004) NBCCS secondary to an interstitial chromosome 9q deletion. Clin Exp Dermatol 29: 542–544

Johnson RL, Rothman AL, Xie J, Goodrich LV, Bare JW, Bonifas JM, Quinn AG, Myers RM, Cox DR, Epstein Jr EH, Scott MP (1996) Human homolog of patched, a candidate gene for the basal cell nevus syndrome. Science 272: 1668–1671

Kimonis VE, Mehta SG, Digiovanna JJ, Bale SJ, Pastakia B (2004) Radiological features in 82 patients with nevoid basal cell carcinoma (NBCC or Gorlin) syndrome. Genet Med 6: 495–502

Lo Muzio L, Nocini PF, Savoia A, Consolo U, Procaccini M, Zelante L, Pannone G, Bucci P, Dolci M, Bambini F, Solda P, Favia G (1999) Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome. Clinical findings in 37 Italian affected individuals. Clin Genet 55: 34–40

Marsh A, Wicking C, Wainwright B, Chenevix-Trench G (2005) DHPLC analysis of patients with Nevoid Basal Cell Carcinoma Syndrome reveals novel PTCH missense mutations in the sterol-sensing domain. Hum Mutat 26: 283

Midro AT, Panasiuk B, Tumer Z, Stankiewicz P, Silahtaroglu A, Lupski JR, Zemanova Z, Stasiewicz-Jarocka B, Hubert E, Tarasow E, Famulski W, Zadrozna-Tolwinska B, Wasilewska E, Kirchhoff M, Kalscheuer V, Michalova K, Tommerup N (2004) Interstitial deletion 9q22.32–q33.2 associated with additional familial translocation t(9;17)(q34.11;p11.2) in a patient with Gorlin–Goltz syndrome and features of Nail–Patella syndrome. Am J Med Genet A 124: 179–191

Miller SA, Dykes DD, Polesky HF (1988) A simple salting out procedure for extracting DNA from human nucleated cells. Nucleic Acids Res 16: 1215

Olivieri C, Maraschio P, Caselli D, Martini C, Beluffi G, Maserati E, Danesino C (2003) Interstitial deletion of chromosome 9, int del(9)(9q22.31–q31.2), including the genes causing multiple basal cell nevus syndrome and Robinow/brachydactyly 1 syndrome. Eur J Pediatr 162: 100–103

Reifenberger J, Wolter M, Weber RG, Megahed M, Ruzicka T, Lichter P, Reifenberger G (1998) Missense mutations in SMOH in sporadic basal cell carcinomas of the skin and primitive neuroectodermal tumors of the central nervous system. Cancer Res 58: 1798–1803

Sasaki K, Yoshimoto T, Nakao T, Minagawa K, Takahashi Y, Watanabe Y, Tanabe C (2000) A nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome with chromosomal aberration. No To Hattatsu 32: 49–55

Shanley S, Ratcliffe J, Hockey A, Haan E, Oley C, Ravine D, Martin N, Wicking C, Chenevix-Trench G (1994) Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome: review of 118 affected individuals. Am J Med Genet 50: 282–290

Shimkets R, Gailani MR, Siu VM, Yang-Feng T, Pressman CL, Levanat S, Goldstein A, Dean M, Bale AE (1996) Molecular analysis of chromosome 9q deletions in two Gorlin syndrome patients. Am J Hum Genet 59: 417–422

Strange RC, El-Genidy N, Ramachandran S, Lovatt TJ, Fryer AA, Smith AG, Lear JT, Ichii-Jones F, Jones PW, Hoban PR (2004a) PTCH polymorphism is associated with the rate of increase in basal cell carcinoma numbers during follow-up: preliminary data on the influence of an exon 12–exon 23 haplotype. Environ Mol Mutagen 44: 469–476

Strange RC, El-Genidy N, Ramachandran S, Lovatt TJ, Fryer AA, Smith AG, Lear JT, Wong C, Jones PW, Ichii-Jones F, Hoban PR (2004b) Susceptibility to basal cell carcinoma: associations with PTCH polymorphisms. Ann Hum Genet 68: 536–545

Wicking C, Bale AE (1997) Molecular basis of the nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome. Curr Opin Pediatr 9: 630–635

Wicking C, Shanley S, Smyth I, Gillies S, Negus K, Graham S, Suthers G, Haites N, Edwards M, Wainwright B, Chenevix-Trench G (1997) Most germ-line mutations in the nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome lead to a premature termination of the PATCHED protein, and no genotype–phenotype correlations are evident. Am J Hum Genet 60: 21–26

Xie J, Murone M, Luoh SM, Ryan A, Gu Q, Zhang C, Bonifas JM, Lam CW, Hynes M, Goddard A, Rosenthal A, Epstein Jr EH, de Sauvage FJ (1998) Activating smoothened mutations in sporadic basal-cell carcinoma. Nature 391: 90–92

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Soufir, N., Gerard, B., Portela, M. et al. PTCH mutations and deletions in patients with typical nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome and in patients with a suspected genetic predisposition to basal cell carcinoma: a French study. Br J Cancer 95, 548–553 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6603303

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6603303

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Ocular manifestations in Gorlin-Goltz syndrome

Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases (2019)

-

Nevoid Basal Cell Carcinoma Syndrome (Gorlin Syndrome)

Head and Neck Pathology (2016)

-

PTCH1 duplication in a family with microcephaly and mild developmental delay

European Journal of Human Genetics (2009)

-

Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome (Gorlin syndrome)

Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases (2008)

-

Heterozygous mutations in the tumor suppressor gene PATCHED provoke basal cell carcinoma-like features in human organotypic skin cultures

Oncogene (2008)