Key Points

-

The lack of access to NHS dental services has been highlighted recently.

-

This study sets out a framework for analysing and interpreting data to assess the extent of access to health care services.

-

The results show that almost 80% of adults in Scotland have had access to NHS GDS over a six-year period, a higher rate than conventional estimates suggest.

Abstract

Objective Recently the issue of access to health services has been brought into sharp focus by clear evidence of rationing — patients queuing for NHS registration — in the NHS General Dental Services (GDS). Conventional estimates suggest that about 50% of adults are registered per annum. This paper demonstrates that these conventional measures of access and utilisation can generate potentially misleading inferences.

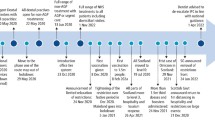

Design By analysing individual-level claims data from over 35,000 patients over six years we are able to: identify the underlying patterns of utilisation that generate the aggregate 50% registration rate; provide more detailed estimates of utilisation and access; and suggest possible determinants of the patterns of utilisation we observe.

Setting Primary care health services.

Results In contrast to conventional estimates of access we find that close to 80% of the adult population in Scotland has had access to GDS over a six year period. Moreover, we find that the population is comprised of a relatively large group of patients (30% of the population) who access GDS at least once a year and a substantial group (19% of the adult population) who access services only once in six years. The groups who access services at intermediate frequencies are less numerous.

Conclusions Assessing the effectiveness of the public provision of health care services requires accurate information regarding access to those services. This paper sets out a framework for analysing and interpreting longitudinal data to provide information on the extent of access to health care services.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ensuring access to health services is a key objective of health care policy. Access was a central component of both the recent Office of Fair Trading investigation into pharmacy services in the UK and the new GMS contract.1,2 Recently the issue of access has been brought into sharp focus by clear evidence of rationing in the form of patients queuing for NHS registration in the NHS General Dental Services.3 The purpose of this paper is to assess the extent of access to the publicly funded General Dental Service (GDS) by adults in Scotland. A number of sources indicate that approximately 50% of the population of Scotland is registered with an NHS dentist at any point in time. This observation does not, however, provide evidence regarding the extent to which the stock of registered individuals changes over time. Thus, the observation of 50% of the population being registered is consistent with a broad range of patterns of access including either the same group of individuals accessing NHS dental services at least once every year, or a greater proportion of the population accessing services but doing so infrequently. In planning dental services and assessing the effectiveness of public provision, it is important to know which of the competing possibilities corresponds to the true position.

This paper demonstrates that conventional measures of access and utilisation can generate potentially misleading inferences. Using data on individual patients, observed over a six year period, we are able to identify the underlying patterns of utilisation. These generate the aggregate 50% registration rate and thus provide more detailed estimates of utilisation and access, and suggest possible determinants of the patterns of utilisation we observe.

Method

In the context of NHS General Dental Services, contact with a GDP results in a claim. The source for our data is MIDAS@DHSRU, which is an anonymised dataset containing all NHS GDS claims in Scotland. Our analysis is based on a 1% random sample of patients for whom a claim is recorded at any time during the period January 1997 to December 2002. The sample consists of 35,863 patients for whom there are a total of 172,552 claims for treatment. Table 1 provides some descriptive statistics for this sample. Table 1 shows, for example, that: the average age of a patient claiming for NHS dental treatment is 45; 57% of claims were made on behalf of female patients; and 79% of all courses of treatment had at least one 'diagnosis' claim.

Conventional estimates of utilisation

In the analysis that follows we adopt a specific measure of utilisation. To conform with some of the previous empirical literature in this area and in order to ensure comparability across other data sets, the empirical measure of utilisation we adopt is participation: whether an individual uses any General Dental Services at least once in a year.4

Of the 35,863 patients in the sample, Table 2 shows that about 52% participated in 1997 and about 47% participated in 2002. These figures correspond closely to the suggestion5 that approximately 50% of the adult population is registered or receiving treatment at any point in time.

While useful in providing cross sectional information on the aggregate use of NHS dental services, Table 2 fails to exploit the underlying individual-level dynamic data that generate the aggregate data. In particular this table does not reveal whether the participants are the same individuals in each time period or an ever changing stock of patients. For example, an observed 50% participation rate is consistent with half the population receiving treatment every year and the other half never receiving any NHS treatment, but is also consistent with every individual in the population receiving treatment once every two years. In the first case there may be a substantial access problem in that half the population never sees an NHS dentist, whereas in the second case there is 100% access to NHS services, albeit at reduced frequency. From the perspective of planning and formulating policy towards the GDS these two cases are clearly substantially different.

In addition to these extreme examples there are a number of other configurations of individual participation behaviour that may generate an aggregate participation rate of 50%. To discriminate between these configurations, and thus be in a position to assess the effectiveness of services delivery, longitudinal or panel data are required which record individuals' participation histories over a (usually) relatively short time period.

The composition of use using panel data

Our data source — MIDAS@DHSRU — permits the decomposition of the aggregate participation rates from Table 2 into each individual patient's pattern of participation over time. Table 3 illustrates the seven most frequent patterns of participation in the GDS in Scotland over six years. A '1' in the 'Pattern' column indicates that a patient participated in that year while a '0' indicates that they did not. Therefore, of the 35,863 patients identified over the six years of the sample, 5,847 (16.3% of the sample) patients attended in each of the six years. In contrast, 3,125 (8.7%) patients participated in 1997 but were not observed in the sample thereafter.

Table 3 illustrates that the most frequent pattern of claims — accounting for about 16% patients in our sample — is for patients to claim at least once every year. In contrast, the next six most frequent patterns of claims — accounting for almost 35% of patients in our sample — comprise those patients that receive treatment in only one year over the six-year period. Thus participation is split between 'highly regular users' and 'highly irregular' users.

The frequency of participation

The patterns of participation in Table 3 may be influenced by a number of determinants and will almost certainly vary for a given individual over time. However, in order to provide some insight into the nature of participation, we estimate the percentage of the population who participate at different frequencies — once a year, once every two years, and so on — using the simplified model outlined in the Appendix. These estimates are reported in Table 4.

Providing that our sample is representative, Table 4 suggests that an estimate of the percentage of non-users in Scotland is 18.7% — considerably smaller than the often assumed 50%. Moreover, this figure overstates the prevalence of NHS 'non-users' for two reasons. First, access to NHS dental services can occur through utilisation of both community dental (CDS) and hospital dental (HDS) services that are excluded from this analysis. Second, data limitations have restricted our period of investigation to a six year period. Hence, individuals who participate at frequencies lower than once every six years are under-represented in our data.

The determinants of participation

The analysis in the previous paragraph is limited by the assumptions we have imposed upon the determinants of participation. In particular we have assumed that participation patterns are constant over time and are determined exogenously. Clearly this assumption is unrealistic. Indeed, the existing literature suggests a number of possible determinants of participation including health state, demographics, preferences, prices and income.4,6

The precise impact of these determinants on the patterns of participation remains to be identified by future research. However, collecting panel data allows the estimation of (at least) two other determinants of participation that conventional cross sectional or aggregate data are unable to identify: state dependence and individual heterogeneity. State dependence refers to the impact of participation today upon participation tomorrow and is easy to conceptualise within a health context: for example, preventive treatment today may make participation tomorrow less likely. Individual heterogeneity refers to the extent to which a patient's participation rate may depend upon their specific characteristics such as, for example, their preferences for oral health. Our own preliminary, and other4,7 research suggests both factors are large and significant determinants of patterns of participation.

Conclusion

The observation of a relatively fixed proportion of individuals registered with GDPs does not provide reliable information about the extent of access to General Dental Services because of turnover amongst those registered. In this paper we have set out a framework for analysing and interpreting longer run claims data with a view to eliciting information upon overall utilisation and the pattern of access to GDP services in Scotland. This information may be used to assist in planning dental services and assessing the effectiveness of public provision.

We find that, whereas only approximately 50% of the adult population is registered at any point in time, a much larger percentage of the population — close to 80% — has had access to GDP services over a six year period. Our framework permits a more detailed breakdown of the pattern of access than that previously available. We find that the population is comprised of a relatively large group of individuals (30% of the adult population) who access GDP services at least once per year and a substantial group (19% of the adult population) who access services only once in six years. The groups within the population who access services at intermediate frequencies are less numerous. These observations would appear to have important implications for policy reform and beg questions regarding the likely impact of changes in patient charges, changes in the frequency of dental recall, changes in service availability and changes in GDP contracts for the overall impact of GDP services. Finally, while we have identified a number of the potential determinants of participation rates, the impact of these determinants and whether the pattern of participation we observe is optimal — in the sense that it is either cost-effective or equitable — remain questions for further research.

References

OFT (Office of Fair Trading). The control of entry regulations and retail pharmacy services in the UK: A report of an OFT market investigation. London, January 2003.

NHS Confederation. Investing in General Practice — The New General Medical Services Contract. London, February 2003.

Half of Britain has no dentist. The Guardian Wednesday February 18, 2004. http://society.guardian.co.uk/primarycare/story/0,8150,1151018,00.html)

Propper C . The demand for private health care in the UK. J Health Economics 2000; 19: 855–876.

Scottish Executive Health Department. An action plan for dental services in Scotland. Edinburgh, August 2000.

Carr-Hill RA, Rice N, Roland M . Socioeconomic determinants of rates of consultation in general practice based on the fourth national morbidity survey of general practices. Br Med J 1996; 312: 1008–1012.

Jordan K, Ong BN, Croft P . Previous consultation and self reported health status as predictors of future demand for primary care. J Epid Pub Health 2003; 57: 109–113.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Appendix

Appendix

We assume that there are I + 1 groups of individuals within the population. We use i = 0, 1, 2, .., I to indicate a specific group and assume that group i has ni constituent members. For groups i > 0 we assume that each of these individuals accesses the services of a GDP every i years while for group i = 0, we assume that the individuals never visit a dentist. To account for population dynamics, we augment the framework to allow for a fixed proportion δ of the population to exit (death and out-migration) each year, offset by fixed proportion ρ entrants (births and in-migrants).We are interested in knowing how important each of these groups is as a percentage of the population and in order to obtain a closed-form solution for the population groups ni we assume that δ = ρ, which is approximately true for the Scottish population. Hence the number of distinct patients observed in year 1 is:

while in the following year the new patients will be comprised of:

In subsequent years, account must be taken of both the survival of the births from previous years appearing for the first time (in proportion to their treatment group) to be treated and the exit of those as yet untreated members of infrequent treatment groups.

The resulting equations can be summarised as:

or in matrix notation:

N = Mn.

The solution of these equations can then be obtained from:

n = M−1N.

We apply this method to data on N derived from our sample and the results, which express the importance of the different groups of participants as a percentage of the total population, are reported in Table 4.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tilley, C., Chalkley, M. Measuring access to health services: General Dental Services in Scotland. Br Dent J 199, 599–601 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4812905

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4812905

This article is cited by

-

Delivering alcohol screening and alcohol brief interventions within general dental practice: rationale and overview of the evidence

British Dental Journal (2011)

-

General dental practitioner views on providing alcohol related health advice; an exploratory study

British Dental Journal (2010)

-

Access to dental health services in Scotland

British Dental Journal (2005)