Abstract

Objective The aim of this study was to determine the relationship between reported dental attendance patterns and the public's perception of how oral health impacts on quality of life (QoL).

Method A national UK study involving a random probability sample of 2,668 adults. Respondents were interviewed in their homes about how oral health affects their QoL and about their dental attendance pattern. Responses were coded as oral health having a negative impact, positive impact or impact in general (either positive and/or negative) on QoL.

Results The response rate was 70% with 1,865 adults participating in the study. 72% (1,340) reported that their oral health affected their QoL in general, 57% (1,065) reported that it had a positive effect, and 48% (902) that it had a negative effect. 61% (1,136) reported to have attended the dentist within the last year – 'regular attenders'. Bivaraite analysis identified association between perception of how oral health impacts on QoL and dental attendance pattern (P < 0.01). When socio-demographic factors (age, gender, and social class) were taken into account in the analysis, 'regular attenders' reported that oral health had greater impact in general on QoL (OR = 1.30, 95% CI = 1.04, 1.63) and, specifically, a greater positive impact (OR = 1.49, 95% CI=1.44, 1.77).

Conclusion Dental attendance is associated with perceptions of how oral health impacts on QoL, specifically enhanced life quality. This may have implications for understanding the health gain of regular dental attendance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The Scientific Basis of Dental Health Education was first produced in 1977 with the aim of defining clear, consistent information that was backed by scientific evidence for the guidance of all those concerned with promoting oral health.1 The recommendation to have 'an oral examination once a year' forms one of the four key messages. However, there is conflicting evidence on the value of regular dental attendance.2,3 Findings from the 1988 Adult Dental Health Survey in the UK revealed that 'regular dental attenders' – those who attended the dentist within the last year – had a higher dental caries experience (DMFT) and had fewer sound untreated teeth.4 In addition, other researchers have raised concerns about the financial implication, loss of time (loss of work hours, for example), discomfort experienced and over treatment associated with regular dental attendance.5,6 It has also been suggested that regular dental attendance may not help prevent the onset of further dental disease.6 On the other hand, there is a large amount of evidence about the benefit of regular dental attendance – for example, less untreated decay, a lower rate of tooth loss and a higher number of functioning teeth (restored or otherwise sound teeth).4,6 Furthermore, it has been argued that regular dental attenders experience less pain, have less 'gaps' from tooth loss and have less untreated disease.2

There is currently a growing interest in oral health outcomes in terms of how oral health affects quality of life. Oral diseases are not usually fatal, but can affect the 'ability to eat, speak and socialise without active disease or embarrassment and contribute to ones general well being'.7 In essence, oral disorders can affect interpersonal relationships and daily activities, and therefore the 'goodness' or 'quality of life'8 A central focus of dental care is to improve the quality of life, to increase survival (absence of oral cancer, presence of teeth) and enable appropriate physical, emotional and social functioning associated with performing normal roles.9 Therefore, understanding how oral health impacts on quality of life may hold the key to determining the value of regular dental attendance in terms of health gain and to understanding patients' behaviour, including dental attendance patterns.10

The aim of this study was to determine the relationship between dental attendance patterns and the public's perceptions of how oral health impacts on life quality, accounting for socio-demographic variations. The rationale for establishing such a link is to draw attention to the wider effects of oral health on life and to introduce a new perspective on the value of regular dental attendance.

Method

Study population

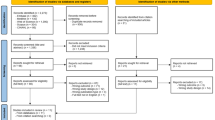

The vehicle for this study was the Office for National Statistics Omnibus Survey in Great Britain. The sampling frame was the British Postcode Address File (PAF). The PAF contains a list of household addresses in the UK, and is the most complete list of addresses in Britain. A random probability sample of 3,000 addresses was selected in a multistage sampling technique. One hundred postal sectors were selected and within each sector 30 addresses were selected randomly. Of the 3,000 selected addresses 2,668 were eligible addresses. Ineligible addresses included new and empty premises at which no private households were dwelling. Trained interviewers sought to carry out face-to-face interviews with an adult respondent (aged 16 or older) at eligible addresses. Only one adult household member was interviewed.

Data collection

Given the lack of agreement about the definition of oral health related quality of life (how oral health affects the quality of life) and what components should be included in its measurement, the approach taken in this research was qualitative. Respondents were asked simply 'In what way does the condition of your teeth, gums, mouth or false teeth reduce your quality of life (negative affects)?' and 'In what way does the condition of your teeth, gums, mouth or false teeth add to your quality of life (positive affects)?' The wording of the questions was developed in consultation with a group of medical sociologists, social scientists, health service researchers, a dental team and members of the public. Responses were recorded verbatim. In addition, information about respondents' dental attendance pattern was collected employing a closed question about time since last dental visit: 'How long ago was your last dental visit to a dentist?' Socio-demographic information was also collected: age, gender and social class background of respondents (based on occupation), information collected routinely collected in all Omnibus surveys.

Data analysis

Open questions allow respondents to use their own words and form their own response categories. This however involves the need for responses to be listed by after the data has been collected, and grouped by theme for development of an appropriate coding frame – 'coding up'. The coding frame was developed from subjecting the written responses from each respondent to content analysis; each response was searched for common themes or categories by both investigators. Conformity of coding was assessed and the data was cleaned to eliminate less obvious errors. The responses were coded as oral health having a negative impact (reducing QoL), positive impact (enhancing QoL), or impacting in general on QoL (either enhancing and/or reducing). In addition, the study group were classified according to dental attendance pattern; those who attended a dentist within the last year – ('regular dental attenders') and those who last attended the dentist over a year ago ('irregular attenders'). The data was weighted to correct for the unequal probability of selection caused by interviewing only one adult per household. Chi square statistics and logistic regression analysis was carried out to determine variations in impact by dental attendance pattern using the statistical package SPSS.

Results

Twenty one per cent (571/2,668) of the adults (16 years or older) refused to take part in the Omnibus Survey, 9% (232/2,268) of the households chosen were not contactable. Of the 1,865 who took part, 5% (87/1,865) declined to answer questions relating to oral health and quality of life. The overall response rate was thus 67%. The socio-demographic profile of the study group is presented in Table 1.

Sixty one per cent (1,136/1865) of the respondents reported to have attended the dentist within the last year – 'regular dental attenders'. Thirty nine per cent (724/1865) reported that it was over one year ago since they last attended the dentist – 'irregular dental attenders'. Five of the respondents did not know how long it was since their previous dental attendance.

Seventy two per cent (1,340/1865) reported that oral health affected their quality of life (in general) either in a positive and/or negative way. Fifty seven per cent (1,065/1865) stated that their oral health added to their quality of life (positive effect) and 48% (902/1865) stated that their oral health reduced their quality of life (negative effect). The most frequently perceived ways in which the British public perceived oral health as affecting quality of life (already reported) are presented in Table 2.

Cross tabulating perceived impacts of oral health on quality of life by dental attendance pattern using Chi Square statistics revealed that the prevalence of perceived impacts varied between regular and irregular dental attenders (Table 3). Regular dental attenders – those who attended the dentist within the last year – more frequently claimed that their oral health impacted on their life quality in general (P < 0.01) and more frequently reported that their oral health enhanced their quality of life (P < 0.01) compared with irregular dental attenders.

Further analysis, using logistic regression analysis demonstrated that dental attendance was a significant factor in perception of whether oral health had an impact on quality of life in general (P < 0.01) and in perception that oral health had a positive impact of life quality (P < 0.01) having accounted for socio-demographic factors: age, gender and social class background, Table 4. Having attended the dentist within the last year (regular dental attenders) was associated with a 30% more likelihood of perceiving that oral health impacted on quality of life (OR = 1.30, 95% CI = 1.04,1.63) and was associated with a 44% more likelihood of perceiving that oral health had a positive effect on quality of life compared to irregular dental attenders (OR = 1.44, 95% CI = 1.18, 1.77). Dental attendance was not a significant factor in the public's perception of how oral health negatively impacted on their quality of life.

Discussion

This study represents one of the first attempts to determine the relationship between dental attendance patterns and perceptions on how the public feel oral health affects quality of life. A qualitative approach was used to capture the public's perception of oral health and its influence of quality of life; whether negative, positive or a mixture of both. Previous measures of quality of life and oral health have predominantly focused only on the negative influences of oral health, the burden of oral disease.11 The current emphasis in health service research, social and clinical sciences is now on the measurement of positive as well as negative health, and its effect on quality of life.12

This study reveals that the British public perceives oral health as affecting quality of life in both positive and negative ways; over half the respondents perceived oral health as having a positive impact (enhancing) on quality of life. This finding highlights the importance of incorporating both positive and negative dimensions in the quality of life research in dentistry, as has been reported elsewhere.13 Oral health is both positive and negative and is likely to influence life quality on both positives and negative ways.

The study classified 'regular attenders' as those who reported attending the dentist within the last year, and all others as 'irregular dental attenders'. Sixty one per cent (1,136) of respondents reported to have attended the dentist within the last year – 'regular dental attenders'. Findings from the Adult Dental Health surveys in the UK have indicated an increase in regular dental attendance behaviour amongst the public over the past three decades and this trend appears to have continued. The high prevalence of reported dental attendance pattern is somewhat similar to that reported in other studies in the UK and US.14,15 However, 'reported' and 'actual' attendance patterns may vary somewhat.16

The value of regular dental attendance, in terms of quality of life, has rarely been investigated. Cushing et al. reported that attendance patterns had little effect on the social impact of dental disease, however, it used the Social Impact of Dental Disease indicator which focuses only on the negative effects of oral health on quality of life and thus was unlikely to tap into its 'positive' value.17 In another study involving older adults in South Australia, Ontario and North Carolina, it was reported that when dental attendance was problem-motivated it was associated with higher levels of social impact, and poorer oral health quality of life.18 In this study, bivariate analysis revealed association between dental attendance patterns and perception of how oral health impacts on life quality. Moreover, having accounted for socio-demographic variables; age, gender and social class background, which are widely reported confounding factors related to oral health quality of life, the association between dental attendance and quality of life remained evident. These findings have implications in highlighting the benefits of regular dental attendance, in terms of health gain, enhanced life quality. Such findings may have implications for those involved in oral health promotion and oral health education strategies, to encourage regular dental attendance, and provides a sound scientific basis for such strategies. However, it should be noted that these findings highlight the association between dental attendance and quality of life and that further investigations are required to investigate whether quality of life improves with dental attendance in a longitudinal study.

Conclusion

The study concludes that there is a relationship between dental attendance patterns and the public's perception of how oral health affects quality of life. Those who reported a dental attendance within the last year felt that oral health had a greater impact on their quality of life in general and, specifically, greater positive impact – enhancing their quality of life, having accounted for socio-demographic variables. This lends support to the Scientific Basis of Dental Health Education recommendation of an oral examination once a year.

References

The Health Education Authority. The Scientific Basis of Dental Health Education: A Policy Document. 4th edn. 1996.

Murray J J . Attendance patterns and oral health. Br Dent J 1996; 181: 339–342.

Kay E J . How often should we go to the dentist? Br Med J 1999; 319: 204–205.

Todd J, Lader D . Adult dental health in United Kingdom in 1988. London: HSMO, 1991.

Reekie D . Attendance patterns. Br Dent J 1997; 182: 169.

Sheiham A . Dental attendance and dental status. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1985; 13: 304–309.

Oral Health Strategy Group. An Oral Health Strategy for England. London: Department of Health, 1994.

Locker D . Oral health: a conceptual framework. Community Dental Health 1988; 5: 3–18.

Gift H C, Atchison K A . Oral health, health and health related quality of life. Med Care 1995; 33: NS57–77.

McGrath C, Bedi R . The value and use of 'quality of life' measures in the primary dental care setting. Primary Dent Care 1999; 6: 53–57.

Slade G D (Ed). Measuring oral health and quality of life. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 1997.

Bowling A . What things are important in people's lives? A survey of the publics judgement to inform scales on health related quality of life. Social Sci Med 1995; 10: 1447–1462.

McGrath C, Bedi R, Gilthorpe M S . Oral health related quality of life – views of the public in the United Kingdom. Community Dental Health 2000; 17: 3–7.

Gratix D, Taylor G O and Lennon M A . Mothers' dental attendance patterns and their children's dental attendance and dental health. Br Dent J 1990; 168: 441–443.

Hayward R A, Meetz H K, Sharpiro M F, Freeman H E . Utilisation of dental service: 1986 patterns and trends. J Public Health Dent 1989; 49: 147–152.

Nuttall N M, Davies J A . The frequency of dental attendance of Scottish dentate adults between 1978-1988. Br Dent J 1991; 171: 161–165.

Cushing A M, Sheiham A, Maizels J . Developing sociodental indicators - the social impact of dental diseases. Community Dent Health 1986; 3: 3–17.

Slade G D, Spenser A J, Locker D, Hunt R J, Strauss R P, Beck J D . Variations in the social impact of oral conditions among older adults in South Australia, Ontario and North Carolina. J Dent Res 1996; 75: 1439–1450.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mc Grath, C., Bedi, R. Can dental attendance improve quality of life?. Br Dent J 190, 262–265 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4800944

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4800944

This article is cited by

-

"Can I please postpone my dentist appointment?" - Exploring a new area of procrastination

Current Psychology (2023)

-

Behavioural intervention to promote the uptake of planned care in urgent dental care attenders: study protocol for the RETURN randomised controlled trial

Trials (2022)

-

Influence of cognitive impairment and dementia on oral health and the utilization of dental services

BMC Oral Health (2021)

-

Prevalence and Factors Associated with Visiting the Dentist Only for Emergency Care Among Indigenous People in Ontario

Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health (2020)

-

Investigating the relationship between multimorbidity and dental attendance: a cross-sectional study of UK adults

British Dental Journal (2019)