Key Points

-

Provides a model surgical safety checklist for use in an outpatient oral surgery setting.

-

Discusses how patient safety incidents can be analysed and audit used to monitor use of an outpatient checklist.

-

Demonstrates how communication and teamwork can be improved to ensure safe management of patients.

Abstract

Extraction of the wrong tooth or teeth is a serious and avoidable clinical error causing harm to the patient. All NHS Trusts in England are required to use a surgical safety checklist in operating theatres to prevent incorrect site surgery and ensure safe management of patients. However, the majority of patients have dental extractions and other oral surgical procedures undertaken on an outpatient basis and these patients are also at risk of having an incorrect site surgical procedure such as a wrong tooth extraction. We describe our experience in developing, introducing and refining a surgical safety checklist for outpatient oral surgery along with the key strategic actions needed to ensure effective cultural change and optimum patient safety in the outpatient setting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background and our experience

The Dental Division of Central Manchester University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust undertakes extractions for approximately 3,500 patients over 5,000 treatment appointments per year, for single or multiple tooth extractions, with the majority of teeth being extracted under local anaesthesia and sedation at the University Dental Hospital of Manchester or Manchester Royal Infirmary. The patient will be seen by a number of different administrative, clinical and nursing staff in their journey from referral to consultation, treatment and at discharge. The oral surgery/oral and maxillofacial teams over this period has consisted of up to seven substantive and honorary consultants, up to five registrars, 12 foundation year 2 trainees, four career development trainees, up to 15 full- and part-time associate specialist and speciality dentists, together with each year approximately 20 new postgraduate students and 80 new undergraduate students and qualified and trainee nursing staff. In a hospital setting like this, with so many operators and nursing staff of different levels of experience potentially involved in the patient pathway from referral through to treatment, the majority of extractions are carried out by an operator who has not been involved in the treatment planning for the patient.

This phenomenon of having an operator who is different to the treatment planner has previously been identified as increasing the risk of wrong tooth extraction.1 In a paper from Israel analysing medical malpractice claims for wrong tooth extraction, most errors occurred during the extraction due to confusion and miscommunication between clinicians within and between clinics.2

Another paper analysing wrong tooth extractions in a hospital in Korea found the most frequent cause of wrong tooth extraction to be cognitive failure and miscommunication.3 The authors further identified risk factors of wrong site surgery to be multiple condemned teeth, partially erupted teeth mimicking third molars, and teeth with gross decay.

Risk factors for wrong site operations have been previously described.4 Several surgeons involved in the same operation, or multiple procedures for one operation, are known risk factors. Other factors such as time pressure due to unscheduled emergency appointments, unclear tooth notation, incorrect patient identification, a missing molar tooth resulting in ambiguity of nomenclature for the remaining molar teeth in the same quadrant, can all increase risk.

An analysis of malpractice claims for wrong tooth extraction in the United States of America however did not find a pattern regarding site and teeth involved.5 The authors noted that there had been no identifiable improvement in reduction of the number of wrong tooth extraction claims despite risk management seminars and online educational courses.

In England, under the Clinical Negligence Scheme for Trusts, the NHSLA recorded 64 claims (settled and outstanding) for wrong tooth extractions by NHS Trusts in England equating to damage costs of £239,919 and a total cost of £572,000 in the period 2007-2012.

Interestingly five of the incidents occurred between 2010 and 2011 in the operating theatre despite mandatory use of the World Health Organisation (WHO) checklist in operating theatres (personal communication).

It is clear that the sequence of events leading to patient harm are multifactorial and have been broadly classified into active failures such as human error, mistakes and violations and latent failures resulting from organisational and workplace conditions which can lead to active errors.

Organisational, managerial, individual performance, team leadership, team dynamics and work environment are all components of a safety culture crucial in managing patients safely.6,7,8,9

To focus improvement in patient safety within the NHS, the National Patient Safety Agency (NPSA), in 2009/2010, issued a list of eight kinds of never events, describing a never event as, 'A serious, largely preventable patient safety incident that should not occur if the available preventative measures have been implemented by healthcare providers'. They identified 111 such events reported to the National Reporting and Learning Agency, of which 57 were wrong site surgery.10 The annual publication by the Department of Health, lists 25 'Never Events', describing these as 'unacceptable and eminently preventable'.11 Wrong site surgery remains the first never event listed in this document.

We know that wrong tooth extractions continue to occur in dentistry.12,13,14 In our Dental Division, despite introduction of a checklist in 2009, between 2009 and 2012 there were five incidents of wrong tooth extraction in an outpatient setting. Of these cases two have resulted in financial settlements totalling £10,500 and two cases remain in legal progress.

While introduction of an outpatient correct site surgery checklist was an important step in the right direction, there was clearly more that was required. This paper describes the further process and strategy that was used to achieve the desired change within our dental services.

Introduction of correct site surgery (CSS) checklist

An outpatient correct site surgery checklist was introduced in 2009 (Fig. 1). The checklist was based on the WHO safer surgery checklist15 which was adapted by the NPSA.16 It consisted of three sections: the correct patient details, correct procedure and a pre-procedure pause when the operator and assistant would confirm that the instruments are applied to the correct tooth, before extraction.

Recognising and Quantifying the problem

Incident reporting and involvement of Clinical Effectiveness Board

All incidents of wrong tooth extraction at University Dental Hospital Manchester are incident reported and presented to the monthly Divisional Clinical Effectiveness Board meeting, along with root cause analysis to ensure actions arising are implemented within a defined timescale.

A culture of incident reporting within an organisation is to be encouraged as it allows identification of problems and subsequently the lowering of overall incidence of harm to patients.

However, it is worth bearing in mind that while incident reporting is essential to identify and act on identified risks, it is an example of a 'lagging indicator' that is, a reactive measure, after an incident has occurred. It does not per se mean that the incident rate of harm will be reduced in the future.17

Active monitoring and measurement, on the other hand, are examples of 'leading indicators'. They indicate that the organisation is taking action to reduce risks.18,19 This is a proactive approach which we undertake as part of our overall strategy towards achieving a reliable reduction in wrong tooth extraction.

Analysing the problem

In order to understand the varied processes leading to wrong tooth extraction we used four separate methods to analyse the problem:

-

1

Root cause analysis of incidents

-

2

Process mapping

-

3

Monthly audits to assess compliance in use of the correct site surgery checklist

-

4

Annual audit to assess compliance in use of the correct site surgery checklist.

Root cause analyses

This was undertaken for each incident of wrong tooth extraction. This helped us to identify the varying causal and key contributing factors leading to the incorrect extractions. These included administrative errors leading to pressures on clinic, inadequate staffing and changeover of supervisor and nurses during the patient's treatment. Lateralisation errors at consultation were not identified at the treatment appointment due to the records not being reviewed fully for consistency and diagnosis not being confirmed before treatment. In other incidents there was lack of communication between the operator and assistant to verify correct treatment on the consent form and an incident where a patient confirmed the incorrect tooth but the team did not undertake any other checks to verify the correct tooth to be extracted.

In all of the above examples the deficiencies contributing to the wrong tooth being extracted were in organisation and management of clinics, staffing, inadequate team communication, inadequacy and failure to check clinical information for consistency at all stages of the patient journey from referral, to consultation, to treatment and in the checking of diagnosis, radiographs, consent and treatment plan. In all cases of wrong tooth extraction there was a failure to follow the correct site surgery checklist by the team.

Process mapping

The aim of this process was to identify areas of weaknesses along the patient pathway from referral to treatment that could increase the risk of incorrect site surgery. An oral surgery consultant and lead nurse chaired this session. Representatives from staff at different levels of seniority, postgraduate and undergraduate students and trainees took part. Areas of concern included: induction of new staff, availability of patient records, patient consent and supervisor responsibility, and communication of treatment details to reception staff. The group identified solutions to the risk areas, which were implemented. The exercise served to engage, educate and raise awareness of the risks, which could lead to wrong tooth extraction. It was also an opportunity to communicate that prevention of wrong site surgery and patient safety was a top priority.

Annual audits

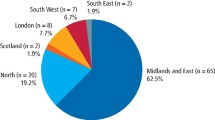

The aim of these audits was to assess compliance in completion of all aspects of the checklist. The target was to achieve 100% compliance with CSS policy. Results from the 2009 audit are shown in Figure 2.

It was noted that clinicians were attempting to follow the correct site policy and in 97% of the cases a form was present in the notes. Compliance, however, was poor as a whole. Reasons for failure to comply included: treatment not written on the white boards, team members did not sign the forms, and checklists being filled retrospectively.

Actions to ensure the purpose of and correct use of the checklist were reinforced with the whole dental team and compliance was re-audited on a monthly basis.

Monthly audits

These were undertaken by a nurse manager, who would intervene where needed, to ensure compliance and provide support in use of the checklist at the dental hospital site.

The results from the monthly repeat audits audit showed successive improvement so that in 2010 and 2011, 100% compliance in completion of the CSS checklist was achieved.

However, despite 100% compliance in use of the checklist, a further incident of wrong extraction occurred in May 2011. The oral surgery consultant had observed during walk around that there were occasions when distractions and deficiencies in teamwork and communication during patient treatment sessions would occur. Results of root cause analyses had already shown these aspects to be key contributors to the wrong teeth being extracted.

Therefore, in the next annual audit in 2011, emphasis was placed on assessing communication and teamwork during dental extraction treatment sessions, whereas previous audits had assessed only completion of the CSS checklist.

Key findings from audit assessing behaviour and communication in use of the correct site surgery checklist

It was apparent that the team were unclear about their roles in undertaking checks and there was a disjointed non-standardised approach with often only the operator verifying certain checks before the patient was treated. The verbal 'time-out' rarely took place and there was confusion around who should undertake checks and write up the whiteboard. Clarification of roles and responsibilities, more communication between the team members to ensure a minimum two persons undertook the checks, and appointment of a checklist coordinator who would confirm that consistent systematic checking of all relevant patient and clinical details had taken place before commencing treatment, was needed.

Clearly there was a need for further education and revision of the existing checklist and policy. This was discussed at the Divisional Clinical Effectiveness Board and the actions taken are detailed below.

Actions taken, lessons shared

Leadership, communication and staff engagement

Following this audit and the latest wrong tooth extraction incident in 2012, the oral surgery consultant called an emergency departmental meeting where outcomes of root cause analyses and lessons to be learnt from these, outcomes and actions from the process mapping sessions and audit outcomes were shared. The Division and Trust patient safety priority was reinforced.

The team were asked for their involvement in how we could ensure that further wrong tooth extractions would not occur.

Actions agreed with immediate implementation while the CSS policy was being revised

It was agreed that the action of calling a verbal 'time out' pause before surgery be implemented with immediate effect and the message, that should any member of the team, at any level of seniority, at any time, note cause for concern in relation to correct management of patients, they should speak up immediately. To ensure that lapses leading to wrong tooth extraction do not occur, a minimum of two person check must take place and where students are working in pairs a third person check to include the supervisor.

The team were made aware that 100% compliance with this process was expected and that this practice was to start with immediate effect with audit of compliance.

The oral surgery consultant revised the existing policy and checklist which was replaced with a Divisional Surgical Safety Checklist Policy (SSCLP) in 2012 for dental extractions under local anaesthesia and sedation. This was ratified at the Dental Division Clinical Effectiveness Board.

The associated surgical safety checklist (SSCL) is shown in Figure 3.

This is currently used for all oral surgical procedures undertaken for patients under local anaesthesia and sedation. It incorporates all of the lessons learnt from investigation of incidents of wrong tooth extractions, results of audits, outcomes of process mapping and staff views. Importantly, it incorporates the NPSA core standards for safer surgery19 and pre-and post-operative briefings identified by Patient Safety First to improve patient safety, enhanced team performance and reliability of key clinical processes.20 It clarifies the roles and responsibilities of team members, includes important pre, per and post-operative checks, communication between team members and between the team and patients to ensure safe management of patients undergoing oral surgical treatments.

The five key aspects of the outpatient Surgical Safety Checklist are:

Team brief

The team introduce each other and clarify their roles. Each member (as a minimum this may be a chairside assistant and operator) is given the chance to raise any concerns in relation to the proposed patient management.

A checklist coordinator is appointed whose role is to confirm with the operator and team that all checks on the checklist have taken place.

Sign in

The dentist completes a thorough review of clinical documentation from referral to treatment plan, patient medical history and relevant dental history, undertaking an intraoral check, ensures the diagnosis is consistent with all documentation and confirms consent with the patient. The assistant and operator agree the treatment on consent form, the correct patient is present and the dentist then completes patient and treatment details on the whiteboard.

Time out

The checklist coordinator calls the verbal 'time out' immediately before instruments are placed on the tooth or before surgery begins. At this point the team deliberately pause to reconfirm that the correct treatment is about to take place for the correct patient at the correct site. It gives all team members the final opportunity to identify and correct any potential error. During the time out stage, the whiteboard, as well as patient records, and for sedation patients the wristband, are used to reconfirm patient consent, ID and procedure details.

Sign out

The checklist coordinator confirms with the team that all safety checks have taken place before the patient is discharged and this is documented.

Debrief

After the patient has been discharged the team openly discuss whether the patient treatment could have been undertaken more safely or more efficiently. Resulting comments and actions are documented. The checklist forms part of the patient records, which are audited annually, whereas the correct use of the checklist is audited monthly in real time.

Any safety incidents are incidents reported by the usual mechanisms.

The policy document which accompanies the checklist also highlights important aspects such as: treatment must not begin or continue without the presence of a chairside assistant; assistant/nurse changeover during treatment must be avoided. If unavoidable the team pauses to allow handover to take place before continuing treatment; all clinicians and students of any professional group and seniority have equal responsibility to ensure patient safety.

SSCL implementation strategy

This was essential to ensure a standardised approach was adopted by all teams.

Communication and launch

The consultant oral surgeon introduced the revised SSCL policy and checklist to the surgical and dental divisions on 17.04.12 at hospital-wide clinical effectiveness meetings by delivering a series of lectures aimed at educating teams in lessons learnt from analysis of incidents of wrong tooth extractions.

Consistency of practice, education and training

To support teams in correct use of the SSCL and to ensure the patient safety message could be accessed by all NHS staff, trainees, university staff and students, a video was produced under the direction of the oral surgery consultant and a trainee. This involved surgical trainees, clinical staff and an undergraduate student demonstrating the key stages of the checklist in 'real-time' use in the management of a patient. The time taken to verify the checks from team brief to debrief was approximately three minutes. It was presented to hospital staff at the subsequent hospital Clinical Effectiveness Day and Audit Meeting in October 2012. The video and policy are accessed by staff via the Trust Intranet and for students via the electronic teaching blackboard and are incorporated in the divisional induction programme and oral surgery induction booklet for all new staff and trainees.

Enforcement and accountability

Departmental Clinical Effectiveness Lead (oral surgery consultant), Clinical Head of Division, Divisional Director and University Heads for undergraduate and postgraduate trainees communicated the importance of compliance with the SSCLP and individual accountability. 'Champions' for students, staff and surgical trainee groups were appointed.

Continual monthly snapshot audits are used to assess compliance and offer guidance in use of SSCL as well as the annual audits to assess correct use of the policy and checklist with now the added advantage of implementing relevant suggestions made by staff in the debrief section thus enabling the checklist to evolve and to enable us to further improve our processes to minimise risk of wrong tooth extraction.

Outcomes

No further wrong tooth extractions have taken place in the last 30 months since implementation of the interim measures contained within the new SSCLP.

In the previous audit poor team communication was highlighted. Now the team checked consent (not just the operator), a verbal 'time out' pause and confirmation was undertaken in all instances, and there were no occasions where an operator worked without an assistant. Communication and teamwork showed significant improvement. It is essential that a checklist coordinator is appointed but audit showed that this did not always happen. As such the checklist has been modified to highlight this aspect and ongoing education and audit will continue.

The team feedback via questionnaire has been very positive, with 52/53 team members stating that the checklist and policy if used correctly ensures safe management of patients and prevents wrong tooth extraction.

Additional benefits noted are that a number of near misses were reported which could have resulted in wrong tooth extraction were identified by the team through use of the checklist and harm was prevented.

Staff now appear to work as a team with more confidence about their roles and responsibilities in relation to safe management of patients, counterchecking patient and clinical details for consistency in a standard way and feel more empowered in the safe management of patients.

Staff, students and trainees have provided positive formal feedback on the video training. They are aware of their role in further suggestions to improve the SSCLP, however, from verbal discussion at departmental meetings and also via the debrief section of the checklist, it appears that staff are happy to continue to use the SSCLP in current format, finding this to be a valuable tool in ensuring the team work together to prevent any likelihood of clinical error.

Staff value use of the whiteboard as a communication and verification tool and see it as integral to the safe surgery process.

The team are periodically updated regarding our performance in the prevention of wrong tooth extractions by the oral surgery consultant and audit results are disseminated. The divisional clinical effectiveness dashboard continues to display absence of wrong tooth extraction since implementation of the SSCL and strategic approach described.

Discussion

Research into the monitoring and measurement of patient safety21 by the Health Foundation concluded that we need to beware of simple single measures such as presence or absence of safety incidents. For example simply recording absence of wrong tooth extractions can be too simplistic as there are many factors that can influence safety and we are in danger of falsely reassuring ourselves and becoming complacent while hazards and risks are not addressed. We agree with the authors that a proactive approach to patient safety is essential and that non-occurrence of adverse incidents can be regarded as a dynamic 'non-event'. Their model of interrelation of patient harm, reliability of systems and behaviours, monitoring of safety, anticipating and being prepared for problems, learning from past harm and responding to and improving safety culture, are all aspects which we have addressed in our approach to reducing the incidence of wrong tooth extraction.

Patient Safety First22 identified use of 'champions', staff inclusion, engagement, behavioural change, executive leadership and leadership walk arounds as the most common drivers for successful implementation of the WHO surgical safety checklist in NHS Trusts.

We have noted that simply introducing a surgical checklist did not prevent wrong tooth extraction. The methodology of audit, when closely scrutinised, showed that assessing completion of the checklist only was not enough to ensure patient safety. It was through observational audit of team behaviour that we were able to identify and address the greatest risks and improve reliability by standardising behaviour.23,24 The process mapping session brought different teams together to highlight weaknesses in our systems and processes which could contribute to wrong tooth extraction. An integral aspect of our approach was to ensure lessons learnt were shared at hospital wide and departmental clinical effectiveness meetings.

The development of a strong patient safety culture where all members of the team are accountable and engaged in the safe management of patients was important and encouragement for near miss incidents, as well as any incidents of wrong site surgery to be reported and investigated, with appropriate and timely actions, has helped to mitigate ongoing risks.25

Effective leadership is essential to managing patient safety.26 To ensure sustained improvement, strong leadership to direct change came from the oral surgery consultant, Division and oral surgery team. Regular 'leadership walkarounds' to effectively and openly engage with staff and provide support and development, took place. The need for such visible and engaging leadership is discussed by Provonost et al. who undertook several surveys of patient safety culture at John Hopkins institution in Baltimore.27

Leading change also meant setting the 'patient safety' tone within our organisation with regular communication to highlight that patient safety is an important and high priority.

We were mindful that while individuals involved in incorrect site surgery incidents are accountable, that we did not develop a blame culture and were able to support the team members involved.

Arriaga et al.28 described a 75% reduction in omission errors with use of a checklist but noted more than a five minute pre-operative training was needed. He also noted that diagnostic errors may lead to incidents. Through use of our training video and checklist emphasising the importance of reconfirming diagnosis and checks for consistency, we hope to reduce such errors. To support teams in implementation of the SSCL, we produced a training video which showed use of the checklist in real time. This was an inclusive process which involved a team of students, nursing staff and trainee surgeons with formal feedback by relevant groups. Representatives from each of these groups went on to become 'champions' in relation to safe surgery.

Mahar29 et al. in their systematic review concluded use of a specific educational intervention, targeting junior dental staff using a training session that included cases of wrong-site surgery, presentation of clinical guidelines and feedback by the instructor, was associated with a reduction in the incidence of wrong-site tooth extractions. While this approach was integral in our implementation strategy, we extended the process to include the whole team and hospital.

Robert et al.30 in 2007 reviewed the evidence to see if a behaviourally specific policy and procedure existed and found no scientific evidence which would guide hospitals in evaluating whether they have an effective policy which staff are aware of and which is being used appropriately to prevent never events. They highlighted the need for team and specifically 'two person' verification of pre- and perioperative checks. We provide a model behavioural checklist which incorporates these aspects in conjunction with an approach to improve safety culture within our division to reduce risk of wrong tooth extraction in an outpatient setting.

Bochard et al.31 conducted a systematic review of the literature to assess the effectiveness of, compliance with, and critical factors for the implementation of safety checklists in surgery. They found compliance between 12% and 100% and compliance with 'time out' of 70-100%.

They concluded that checklists are effective and economic tools that decrease mortality and morbidity but further research relating to implementation is needed. We have presented an implementation strategy which has proved to be successful in a teaching hospital setting. While compliance is essential, we have noted that it is the team communication and meaningful use of checklists that is key in avoidance of critical incidents such as wrong tooth extraction. NHS England recently published a report of the NHS England Never Events taskforce32 in which they conclude that in order to achieve continual reduction in harm we must reduce variation in practice, promote learning from mistakes and improvement activities and promote organisational and professional responsibility through a strategy of standardising operating procedures outside the theatre environment, education and training and harmonising activity to ensure a safer environment for patients. Their intention is to embed this approach widely within the NHS. We have shown how these elements can be implemented in a secondary care dental setting such as ours.

In our experience mere existence of a policy and checklist did not prevent wrong site surgery. We note that in an environment such as ours where team members are constantly changing, to be clinically effective, strong committed leadership in patient safety, standardisation of processes, cross checks, monitoring and measuring compliance, evaluating, sharing lessons from incidents, reviewing processes, educating and empowering our teams, measuring effective team communication, strategic direction and feedback from frontline staff were prerequisites to creating a strong patient safety culture. This is a managed, continuous, process requiring commitment from all stakeholders, and will need to be sustained to remain effective.

References

Wachter R M, McDonald K M . Making health care safer: a critical analysis of patient safety practices [Report Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 43]. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2001.

Peleg O, Givot N, Halamish-Shani T, Taicher S . Wrong tooth extraction: Root cause analysis. Quintessence Int 2010; 41: 869–872.

Chang H H, Lee J J, Cheng S J et al. Effectiveness of an educational programme in reducing the incidence of wrong-site tooth extraction. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2004; 98: 288–294.

Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. Sentinel Event Alert. A follow-up review of wrong site surgery. Report No. 24, 2001. Available at: http://www.jcaho.org.

Lee J S, Curley A W . Prevention of wrong-site tooth extraction: clinical guidelines. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2007; 65: 1793–1799.

Reason J . Human error: models and management. BMJ 2000; 320: 768–770.

Reason J . Beyond the organizational accident: the need for 'error wisdom' on the frontline. Quality and Safety in Health Care 2004; 13: 28–33.

Report for methods and measures working group of WHO patient safety, April 2009. Human factors in patient safety: review of topics and tools. WHO/IER/PSP/2009.05.

Carthey J, Clarke J . Patient safety first implementing human factors in healthcare 'how to' guide. Version 20100520.

National Patient Safety Agency never events annual report 2009/2010. The Stationery Office and available from: www.tsoshop.co.uk.

Department of Health U K. Policy document. The Department of Health Never Events list 2012/2013. www.dh.gov.uk/publications.

Dental Defence Union. Beware of wrong tooth extraction warns DDU. 22 April 2009.

Briggs L . Pitfalls of pulling teeth. The Probe February 2011.

National Health Services Litigation Authority http://www.nhsla.com.

World Health Organisation. Safe surgery saves lives. 2008. Available at: www.who.int/patientsafety/safesurgery/en/ (accessed 19 September 2014).

National Patient safety Agency. WHO surgical safety checklist 2009. Available at: www.nrls.npsa.nhs.uk/resources/?entryid45=59860 (accessed 19 September 2014).

Health Services Executive. Developing process safety indicators: a stepbystep guide for chemical and major hazard industries. HSG254. HSE Books, 2006. Available at: http://books.hse.gov.uk/hse/public (accessed 19 September 2014).

OECD. Guidance on Safety Performance Indicators. A Companion to the OECD Guiding Principles for Chemical Accident Prevention, Preparedness and Response. Guidance for Industry, Public Authorities and Communities for developing SPI programmes related to chemical accident prevention, preparedness and response. Paris: OECD Publications, 2005.

National Patient Safety Agency. Available at: http://www.nrls.npsa.nhs.uk/ (accessed 19 September 2014).

Patient Safety First. Improving communication and teamwork. Five steps to improving perioperative communications and teamwork using the WHO Surgical Safety Checklist. August 2009. Available at: http://www.patientsafetyfirst.nhs.uk/ashx/Asset.ashx?path=/Intervention-support/WHO%20Checklist%20five%20steps.pdf (accessed 19 September 2014).

Vincent C, Barnett S, Carthey J . The measurement and monitoring of safety. The Health Foundation, 2013.

Patient Safety First. Implementing the surgical safety checklist: the journey so far. June 2010. Available at: http://www.patientsafetyfirst.nhs.uk/ashx/Asset.ashx?path=/Implementing%20the%20Surgical%20Safety%20Checklist%20-%20the%20journey%20so%20far%202010.06.21%20FINAL.pdf (accessed 19 September 2014).

Baker D P, Day R, Salas E . Teamwork as an essential component of high-reliability organizations. Health Serv Res 2006; 41: 1576–1598.

Burnett S, Franklin B D, Moorthy K, Cooke M W, Vincent C . How reliable are clinical systems in the UK NHS? A study of seven NHS organizations. BMJ Quality Safety 2012; 21: 466–472.

National Patient Safety Agency. Seven steps to patient safety in primary care. 2006. Available at: http://www.nrls.npsa.nhs.uk/resources/collections/seven-steps-to-patient-safety/ (accessed 19 September 2014).

Reason J . Managing the risks of organizational accidents. Aldershot: Ashgate, 1997.

Pronovost P J, Weast B, Holzmueller C G et al. Evaluation of the culture of safety: survey of clinicians and managers in an academic medical centre. Qual Saf Health Care 2003; 12: 405–410.

Arriaga A F, Bader A M, Wong J M et al. A simulation-based trial of surgical-crisis checklists. N Engl J Med 2013; 368: 1459–1460.

Maher P, Wasiak J, Batty L, Fowler S, Cleland H, Gruen R L . Interventions for reducing wrong-site surgery and invasive procedures. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012; CD009404.

Robert K M, Martin A M, Yasser D et al. Achieving the National Quality Forum's 'Never Events': prevention of wrong site, wrong procedure, and wrong patient operations. Ann Surg 2007; 245: 526–532.

Bochard A, Schwappach D L, Barbir A, Bezzola P . A systematic review of effectiveness, compliance and critical factors for implementation of checklists in surgery. Ann Surg 2012; 256: 925–933.

NHS England. Standardise, educate, harmonise. Commissioning the conditions for safer surgery. Report of the NHS England Never Events Taskforce, February 2014. Available at: http://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/sur-nev-ev-tf-rep.pdf (accessed 19 September 2014).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Saksena, A., Pemberton, M., Shaw, A. et al. Preventing wrong tooth extraction: experience in development and implementation of an outpatient safety checklist. Br Dent J 217, 357–362 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2014.860

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2014.860

This article is cited by

-

High-reliability organisation principles implemented in dentistry

British Dental Journal (2022)

-

Surgical safety checklists for dental implant surgeries—a scoping review

Clinical Oral Investigations (2022)

-

How to create local safety standards for invasive procedures (LocSSIPs) by engaging the team in patient safety

British Dental Journal (2019)

-

The evolution of patient safety procedures in an oral surgery department

British Dental Journal (2019)

-

Developing agreement on never events in primary care dentistry: an international eDelphi study

British Dental Journal (2018)