Abstract

Study design:

A grounded theory study of 19 adults with spinal cord injury was conducted. Participants engaged in individual in-depth interviews, and took photographs of aspects of their environment that promoted and restricted participation. Analysis consisted of an inductive process of constant comparison. A focus group with participants was held to discuss and contribute to the credibility of findings.

Objectives:

To develop a theoretical understanding of the influences on self-perceived participation for individuals with SCI.

Setting:

Manitoba, Canada.

Results:

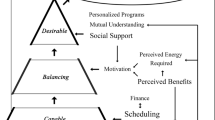

The constructed grounded theory model is summarized as follows: negotiating the body–environment interface is a continuous process for those living with a SCI. Despite the relative stability of their changed body, they live in a changed world, one that is perceived differently after SCI. People use various strategies to interact within their environment, to engage in a process of participation. Intervening conditions are the environmental aspects that serve as barriers or facilitators to this process of participation.

Conclusions:

Study findings lend support to the need for a self-perceived definition of participation. The theory constructed in this study can be used to target interventions intended to improve the participation experiences of individuals with SCI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Approximately 85 000 Canadians are living with a spinal cord injury or subjective terms.3 Society-perceived participation is based on societal imposed norms of what is expected of individuals of a particular age and culture.2 For example, the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health defines participation as ‘involvement in a life situation’7 and distinguishes objective involvement as the object of interest. Although there has been substantial recent research into society-perceived participation and its’ measurement, this body of literature is beyond the scope of this article. In contrast, the self-perceived perspective defines participation in terms of the belonging and connectivity individuals have with their environment.6 Participation is viewed as a continuous process rather than solely a rehabilitation outcome6, 8 and, consistent with the social model of disability, focuses on the lived experience of individuals participating in their lives and communities.9 Studies among individuals with SCI have predominately used society-perceived perspectives to explore participation. However, there are discrepancies in study findings that examine the relationship between participation and life satisfaction of adults with SCI, with some identifying a positive relationship,10, 11 and others a limited relationship.12 Some studies of adults with SCI have identified that participation is enabled as environmental barriers are removed,13, 14 while others have found that environmental barriers have a limited influence on participation.12 Differences in these studies may in part be attributed to the differing conceptualization and measurement of participation.

Two recent studies have examined self-perceived participation among people with SCI. Van de Velde et al.15 conducted a study of 11 men with SCI during the transition from hospital to home, and found that participation was depicted as a set of values that included occupying time, achievement, inclusion and having a sense of control through activity. These authors stressed the need for future research to explore the experiences of individuals with SCI who had with a greater range of diversity, including longer time living in the community, and augmenting findings using participatory research methods. Recently, Newman16 engaged 10 people with SCI in a photovoice study that explored the barriers and facilitators to community participation, and concluded that rehabilitation professionals need to better understand the communities in which people with disabilities live their lives.

Although there is a developing understanding of participation among adults with SCI, there is a pressing need to develop a more comprehensive theoretical rendering. Constructing an understanding of participation that privileges the perspectives of those who hold the lived experience of SCI, adds to the developing understanding of the construct of participation.14, 15, 17 The purpose of this study was to advance an understanding of how adults with SCI participate in their daily life and within their communities, to promote opportunity for participation.

Methods

Theoretical foundation

This study was theoretically guided by symbolic interactionism, with the assumption that humans act in a way consistent with the meaning they ascribe to a situation. Through naturalistic inquiry of inter-subjective experience and inductive analysis, researchers can come to understand this ascribed meaning conveyed through language and communication.18, 19 Constructivist grounded theory20 was used as a means to understand the social processes and structures, and to develop theory related to participation experiences of adults with SCI.

Participants

Participants in this study were adults residing in one Canadian province with SCIs and were recruited through advertisements directed toward service organizations and rehabilitation facilities. Initial sampling focused on recruiting participants who varied with respect to gender, age, rural versus urban-dwelling, socioeconomic status and length of time since injury. In keeping with development of grounded theory and the use of theoretical sampling,20 the researchers adopted an iterative process of data collection and analysis. Thus, subsequent sampling attempted to select participants based on their ability to expand on the emerging categories.20 An a priori sample size was not developed, rather saturation of categories achieved through constant comparative analysis, or when additional interviews were found to add little or no new information, dictated the final sample size. In total, 19 adults with SCI were recruited. Table 1 provides participant demographics.

The study was approved by a University Health Research Ethics Board, and all participants provided informed consent before data collection. As the data collection occurred over a prolonged period, a process of reaffirming consent was used to ensure participants’ interest in continuing. As a result, some participants chose not to continue the full study (n=19 completed the first interview; n=15 completed the second interview/contributed photographs; and n=13 contributed to verification of the findings).

Data collection

This study included three primary data collection methods. First, participants engaged in in-depth individual interviews to gain an understanding of each individual’s experience of disability, and to gather detailed descriptions of the meaning and experience of participation. Each interview was digitally recorded and transcribed in full, at which point personal identifiers were removed and pseudonyms assigned. Field notes were recorded to describe the context and perceptions of the interviews.

Second, photovoice was used to capture participants’ insider perspective on the meaning of, and influences on, participation. Photovoice is a participatory and empowerment focused method, whereby participants inform researchers of community assets and deficits using self-selected photographs.21 Participants were asked to photograph 10–15 relevant individual, family and community life experiences that illustrate the meaning and experience of social and community participation. Camera accessibility was addressed for those participants who required adaptations. Some participants required selection of specific commercially available equipment so that it was usable (such as larger, non-recessed shutter buttons), while other participants required mounting devices or adaptive switches. In consultation with a rehabilitation engineer, individualized assessments were completed with each participant, and subsequently cameras were purchased and/or modified to ensure independent use of the camera. In all, 9 of 19 participants required some type of camera modification.

The final method of data collection included a second interview that was focused using the SHOWED method,22 a technique that encourages discussion on the meaning of the photos to the participants. The photos and emergent ideas around participation were analyzed and presented back to participants in one of two focus groups or through a photo book conducted the interviews, camera assessments and focus groups.

Data analysis

Data analysis focused on the meanings, intentions and actions of the participants using a process of constant comparative analysis.20 Each interview transcript was subject to repeated readings to gain a sense of the whole and to code the processes occurring. Analytic ideas that emerged during the initial coding were manually recorded on the right side of the transcript and used to question subsequent interview transcripts. Next, a process of focused selective coding ensued, with an intent to select the most significant and relevant codes.20 This analysis was conducted through a process of posing and answering the question: Which topics were most important and relevant to the participant in the interview? This process resulted in the development of a focused coding summary for each participant. The focused coding summary of each participant was compared between participants, as each new participant entered the study, and as his or her data was added to the overall data. This process resulted in a combined analysis of focused coding, where the focused codes were no longer related only to an individual participant, but to the participants as a group. Through a process of memo writing, some codes were raised to the level of categories, and used to label generic processes. Next, categories were compared with examine linkages and relationships.20

Throughout the analysis, specific attention was given to terms or phrases that represented an experience.20 These codes aided in constructing and explicating analytic categories. For example, the term ‘whirlwind’ was used by a participant to describe the time after SCI, when the person returned home. Here, he described experiencing a different and altered embodied self while at the same time the environment he returned to was the same as before his injury, creating a feeling of turmoil and loss of autonomy. Eventually, the repeated recognition of this experience in the individual interviews led to the core phenomenon depicted in the study findings. To aid in the process of theoretical coding, a series of tables was developed as the categories were constructed. Finally, a model was developed and continuously refined throughout this process to conceptualize and relate the categories.

With intent to further elaborate on or explicate the emergent categories, focus group and follow-up interview data were added into the analysis. However, while the inclusion of this data was useful in theory refinement, the addition did not create a substantial change to the developed theory.

Rigor was addressed in several ways.23 Participants had a prolonged engagement in the topic area, promoting on-going reflection and development of the findings. Use of multiple data collection methods and sources contributed to triangulation of findings. In the focus groups, participants were presented with the findings and confirmed that the results reflected their participation experiences. Transferability was addressed by providing detailed descriptions of participants and reporting of data using the participants’ direct quotes.23 An audit trail was developed throughout the data analysis process, and the first author reviewed emergent interpretations with peers with expertise either in qualitative inquiry or in working with individuals with SCI. Reflexivity was maintained through on-going documentation in a research log and juxtaposing this reflection against the data in the analysis process.

Results

Overall, the categories that emerged held true regardless of the age, gender or length of time since injury of participants. However, some differences were evident between participants who had sustained their injury in childhood or as an adult, such as those described in the category living in a changed world. The variations in how the categories were expressed provided dimension and nuance to the constructed categories.

Living in a changed world

Living in a changed world was the core category, characterized as the time after SCI when the person has returned home from hospital. Although their world did not structurally change after SCI, their interaction within their world changed. One participant used the term ‘whirlwind’ to describe the time after SCI when this changed world was first experienced: ‘Yeah, um, to go from, you know, pretty much complete freedom in life, being able to do whatever you wanted … to having to, if you want to do something there’s so many more factors you have to take into account, you know. Ah, can I even get to the place I want to go?’ What was previously taken for granted became a barrier to community engagement. As Kevin said: ‘You don’t realize how inaccessible the world is until you are in one of these (wheelchair).’

Involvement in previously valued activities was altered to the point of losing the essence of the activity, and many did not return to previously important activities. For instance, Harrison stated:

I haven’t participated in, like, things I used to do before. Like I don’t really, I guess with the boxing for example. I’ve gone a few times just to watch fights and stuff like that, but I haven’t really done too much more other than that ... I guess I don’t, I don’t know, don’t really like going there too much. It’s just too different, I guess.

Although some barriers might be surmountable, the modifications required made engaging in the activity unacceptable, as David shared: ‘I’ve tried every which way to try to get back to golf. I was an avid golfer and I’ve tried different chairs and different ways to hold them it just wasn’t there.’

This experience was different, however, for those who grew up with a SCI, where the introduction of assistive technology often created a change in world perception. As a child, Vern was dependent for mobility and lived in an institutional setting. He describes first acquiring a power wheelchair: ‘But I get this electric wheelchair, suddenly I can go down the hallway and I can visit anybody and I can, I can go from one room to the other.’ Although facing the same environmental barriers as those who sustained an injury later in life, they had created their world around them through choice of accessible living situations, selection of career and engagement in leisure activities.

Negotiating the body/environment interface

The core psychosocial process constructed was in response to the question: ‘How do individuals with SCI create opportunities for participation?’ Participants engaged in a process of negotiating the body and environment interface to seek and create opportunities for participation. Part of the SCI experience related to bodily changes. Although a few participants expressed concern about pressure sore development and pain, it was not predominant. Rather than limiting participation, participants modified activities and made choices based on these physiological issues. Some reported engaging in only one extra activity beyond their daily routine per day, such as Tom, who described how his daily routine, travel arrangements and selection of AT are highly driven by his desire to prevent pressure ulcer development.

The individual’s biological or social interpretation of disability was based upon their ascription to the cause of disability. This belief system resulted in different ways of negotiating the body–environment interface. Wilson and Josef represented two extremes of this viewpoint. Wilson, who had a life-time experience of having had a SCI, was involved in advocacy at a policy level, sharing a picture of his participation in a political meeting around an accessibility issue, and describing it as follows: ‘So this photo to me in a sense means change can be done.’ On the other extreme, Josef took an individualized approach to addressing the barriers that existed, stating: ‘As I said before I also like the idea of trying to adapt yourself, so I, I wanted more training with going onto and off of curbs.’

Although participants acknowledged environmental barriers, they tended to address them in individual ways, often using technological or human resources. For example, Tom bought a new wheelchair: ‘And in most places … I can’t get into cause they just have 2 or 3 inch steps and this chair will … ... it states 4 inches.’

One aspect of negotiating the body–environment interface was recognition of accessibility issues. Considering how one would overcome barriers before going out became important, as Tom relayed: ‘I think once you land up in a chair, you think about it a lot more. What ah … where can I go? How can I get in there? Will I take someone to help me?’ Furthermore, considering whether a place would be accessible meant sometimes choosing not to go somewhere that is inaccessible, implementing strategies to enable access or limiting ones’ choice of activities. Despite increased societal awareness of the need for accessible public spaces, many inaccessible public buildings and facilities continue to exist. For participants in this study, these inaccessible public spaces now required consideration.

Societal attitudes, which before SCI were often unrecognized by participants, became a new concern. Elinor described dealing with negative attitudes as a new wheelchair user:

The worst thing that I always remember is when I first got out of the hospital I was at ... And this woman came barreling out and almost banged into me. She just looked at me and she says ‘You people shouldn’t be in stores like this. All you do is cause troubles for people like me’.

Even family and established friendships were not immune from the expression of hurtful attitudes. Fynn took a picture of a friend that he had recently re-established a friendship with, commenting: ‘The last time I seen him I was in the hospital bed fifteen years ago … it took a long time for him to accept my being in the chair.’

Engaging in a process of participation

Participants described participation as an experience, explaining what it meant ‘to participate’ rather than identifying specific activities or roles. Participation was viewed as the consequence of negotiating the body–environment interface, and was described in four ways: inclusion, opportunity for reciprocity, accomplishment and autonomy. Although these experiences were lived out in the context of a meaningful activity or relationship, the activity or relationship was a means, rather than an end, for achieving that experience. While nearly all of the participants described the experience of inclusion, the other three participation experiences were each described by greater than half of the participants.

Terms used to describe the sense of inclusion included: ‘feeling a part of something’, ‘feeling welcome’ and a ‘sense of belonging’. A social setting was the venue for these feelings, and included the sense of meaningful involvement in activities. The experience of inclusion was contrasted with segregation, a feeling experienced by one participant when visiting a restaurant with higher tables that prevented him from sitting with friends. A second participation experience was reciprocity, or giving back, and was accomplished through sharing ones’ life story, volunteer work or educating others. As Nancy described: ‘it’s dealing with ways or possibly improving your community and enriching, not only your own life, but other people’s.’ A third participation experience was a sense of accomplishment, described by Wilson as ‘contributing effort toward something.’ Sports and leisure activities were important venues for accomplishment to be actualized. For example, David conveyed how his involvement in antique car restoration resulted in a feeling of accomplishment. The final participation experience expressed was autonomy as described by Marlene: ‘to do what you want and where you want and when you want’. This included a sense of control over managing one’s time and the opportunity to make one’s own decisions.

Strategies

Participants in this study engaged in four main strategies to negotiate the body–environment interface: creating an accessible proximal environment; using AT and adaptations; advocating and educating; and gaining information and knowledge. Development of personal space and an accessible environment was a strategy engaged in by all participants. When financially possible, many modified, built or rented accessible homes. Wilson shared a photo, stating: ‘This is my apartment … which is universal design and level entry. This basically just shows how an apartment can be quite beautiful with also being accessible.’

All participants in this study used AT and adaptations, and participants in this study described AT as ‘freedom’ and ‘a way to overcome barriers’. David shared a picture of his leg braces, and captioned it: ‘ just really kept me going for 29 years … without them I would be totally lost.’ When not commercially available, participants developed new technologies to meet their needs, for example, Vern took a picture of a device he developed with rehabilitation engineers:

So I have this hand warmer that I can carry around with me … You know I used to be able to go out at ten above, now I go out at zero above because I know my, I know my hands are not going to get so cold they can’t move.

The importance of AT for leisure was emphasized, as participants used adaptations to engage in sledge hockey, curling, fishing, biking and sailing. The social value of leisure engagement was highlighted, and adaptations supported participants’ ability to engage in family-based activities. For those who owned their own van, the vehicle was viewed as essential for spontaneous community participation. Tom stated: ‘It’s a world of difference having your own vehicle, just get up and go when you want to.’ Having a vehicle allowed for independence and convenience that was not available though public transportation.

Most participants engaged in a wide variety of strategies intended to influence others. Some took a conciliatory approach, others an assertive approach, whereas others found ways to educate society around accessibility issues. Garrett described engaging with others to address accessibility barriers in this way: ‘so you need to do this, and I need to do this, so let’s figure it out’. Often, participants served as an informal resource to others, such as when sharing their experience of living with a SCI or describing how they addressed accessibility issues. Others took an assertive approach to ensuring needs were met and rights were not violated. As Elinor commented: ‘I’ve learned over the years that if you don’t open your mouth, people stomp all over you, they don’t care.’

Persistence and energy were required when engaging in advocacy efforts, as summed up by Vern: ‘ put the ideas out there, you put them out there, and put them out there, and put them out there.’ At times, participants chose not to advocate as they felt to do so would be futile, or they felt patronized. Jayna described one advocacy experience as ‘disheartening and demoralizing’, and Olivia reflected, ‘So many people with disabilities don’t complain … we’re worried about losing services.’

Depending on the situation, other strategies focused on gathering information required for decision making. For example, most participants conveyed how learning whether a space was accessible was an important strategy. Oftentimes a person would be told an environment was accessible only to find out that it was not; Marlene described how she ‘got burned once, didn’t bother getting burned again’. Most wanted to ‘see it for themselves’ and known inaccessible spaces were generally avoided.

Intervening conditions

Intervening conditions were the social, physical, financial and institutional resources of participants, which served as either supports or barriers to participation. The importance of family was evident in the participants’ interviews and pictures, as Olivia stated: ‘Family is like the most important part in my life.’ Beside providing emotional support, family and friends were an invaluable in providing the physical support to overcome accessibility barriers. Most described how friends ‘bumped’ stairs or curbs; such supports enabled access to inaccessible environments. Having these social resources available supported the ability to go wherever one desired. For instance, Nancy stated: ‘If you’ve got the right people around, anything is possible’.

Health care supports were a part of many peoples’ lives, assisting with personal care and home management. Many relayed stories of challenging situations with health or home care staff; finding a good person was a ‘godsend’ (Tom). For some, the local SCI support organization was identified as important, primarily in regard to a specific counselor who advised or assisted them with advocacy efforts.

For those without private transportation, the importance of disability-specific public transportation was stressed. Participants relied on this service, yet felt powerless to express concerns. ‘It puts a little bit of fear in me to say like if they’re going to take away from me, then what’s going to happen to me? My independence goes down so much’ (Olivia).

Funders were viewed as the gatekeepers to obtaining equipment and an adversarial relationship with funders was the norm. Fynn described ‘fighting tooth and nail’ to receive a modified van, illustrating the challenge of obtaining equipment that one needed. Funders wielded perceived power in other ways. For example, when participants tried to supplement their income to make purchases not prioritized by funders, they kept activities secretive for fear of repercussion. Funding policies often appeared unreasonable and lacked transparency, making it unclear how decisions were made, and thus what information should be shared with funders. Despite not knowing the rules, there was a perception that people needed to ‘follow the rules’, or face ramifications.

Community access was a key facilitator of participation for participants. Accessible environments supported people’s engagement in important and meaningful activities. Those with long-standing injuries commented on the improvements they had seen over the years in terms of architectural accessibility and attitudes, with more awareness of the rights of people with disabilities. Garrett, who had traveled internationally, stated he felt ‘blessed to live in North America because you can go somewhere and kind of expect that you’ll probably get in.’ However, photos also captured inaccessible public spaces. Accessibility was often limited by uneven sidewalks, poor parking options and the perceived misuse of assigned handicapped parking stalls, and features of building entrances such as high curbs, stairs and absent automatic door opener buttons. Additional barriers included washroom stalls that could not accommodate wheelchair users and narrow doorways, hallways and aisles. For example, Jayna shared a picture of a school: ‘My son’s school has three levels, and this is how everyone gets to the office, stairs. My son went to this school for seven years and I haven’t seen his desk or classroom in the last four years.’ Pseudo-accessible public spaces, spaces that had some aspects of accessibility yet remained inaccessible, were also frequently identified. For example, Vern identified a building with an automatic button door opener, but with a two-inch ledge into the building, stating: ‘What good is the button, when you can’t get into the building anyway?’

This study confirmed the existence of natural and climatic environment barriers. Public spaces such as parks and playgrounds were generally inaccessible, with ground surfacing identified as the most problematic feature. Sub-zero temperatures, snow and ice were an ongoing challenge. Some participants avoided or minimized outdoor activities, whereas others utilized strategies to address winter barriers, such as driving their wheelchairs on the road to avoid impassable sidewalks: ‘In the summer I’m a pedestrian and in the winter I’m a car’ (Wilson).

Accessibility for participants also addressed the social environment. In general, society was viewed as kind and accommodating, and most felt that if they asked for help it was provided. However, many reported negative interactions and some deemed assistance provided as overly helpful, particularly when unrequested or unsolicited. Tom described it this way: ‘Yeah, everybody wants to help somebody in a wheelchair. At least that’s what it seems to me.’ Others believed that the public lacked disability awareness and would not notice if assistance was needed, avoided interaction, made negative assumptions about the capacity of participants or acted with a sense of entitlement, such as failing to give up priority bus seating. Most participants relayed at least one incident when they were affected by someone’s lack of consideration or hurtful comments. Jayna stated, ‘It only takes one bad apple but still they, they have the loudest voice’ to describe how the negative comments would stand out in their mind.

Discussion

Using symbolic interaction as a framework, the researchers were able to understand both the micro- and macro-level interactions between person and environment as it pertained to his/her experience of participation.24 Participants’ self-selected photos provided an insider perspective of their experiences, consistent with Brown25 who stressed that what is perceived as a barrier or support ‘varies across insiders because it is shaped not by the fact of disablement per se but by that fact filtered through the person’s experiences, values and beliefs’. The interviews driven by the photos provided an enhanced understanding of how participation was perceived in the context of self-selected activities.

The study findings concur with the small body of previous work specifically focused on self-perceived participation among people with SCI,15 strategies people with SCI use to enhance autonomy,26 as well as research around environmental supports and barriers expressed by those with SCI.16 Taken together, the findings support the development of an interpretive theory20 to conceptualize self-perceived participation for individuals with SCI. The value of developing theory is in depicting the findings in a way that is reflects the experiences of the individuals who contribute to it, while organizing and relating findings in a manner that have broader societal application. The grounded theory model constructed from the data is summarized as follows: ‘negotiating the body/environment interface’ is a continuous process for those living with a SCI. Despite the relative stability of their changed body, they ‘live in a changed world’, one that is perceived differently after SCI. People use various strategies, to engage in a ‘process of participation’. Various intervening conditions serve as barriers or facilitators of participation, related to the physical, social and attitudinal environments. These conditions influence the persons’ ability to negotiate their body/environment interface and subsequently direct their selection of strategies.

Describing participation as a set of values is consistent with the findings of recent qualitative studies on the self-perceived meaning of participation15, 17, 27 and a mixed methods study that highlighted the importance of autonomy, and how perceived lack of choice and control that people with SCI experienced impacted social participation and quality of life.28 Participants in this study did not define participation by type, or amount, of engagement in activities, rather they sought ways to satisfy their participation needs of accomplishment, autonomy, opportunity for reciprocity and inclusion through the use of strategies they engaged in with support of, or in spite of, environmental factors.

Similar to other models,7, 29 the environment was experienced in a transactive manner that promoted opportunities and created challenges to participation. Individuals actively interacted within their environment to develop a sense of identity, establish meaning and engage in a process of participation. Engagement within personal and community environments was essential to negotiating the body–environment interface. Corbin and Strauss30 suggest that environmental changes that are supportive and enhance the ability of individuals with disabilities positively affect ‘body performance’ and reduce the ‘biographical work’ required to reconcile the body–environment interface. Accordingly, the findings in this study confirmed the research of others regarding the importance of a strong social network offering physical, social and emotional support.16, 28, 31 The physical barriers experienced by participants in this study have also been reported in other studies13, 16, 28, 31, 32 and the lack of appropriate transportation has been frequently identified as an environmental barrier for individuals with SCI.8, 12, 13 To address these barriers, certain technologies were found to be imperative in reconciling the body–environment interface: access to one’s own vehicle and assistive technology. The importance of a vehicle has been reported previously28, 31, 33 and an extensive body of literature on the importance of assistive technology in serving to ‘broaden the possibilities and opportunities of people with disabilities’27 is in existence.

Accessibility for participants referred to more than the physical environment, it involved ‘enabling dignified inclusion in services, activities and relationships’.34 Negative interactions and societal responses strikingly similar to those of the present study’s participants have been reported previously16, 27, 28, 31 and it was apparent from the study results that attitudinal barriers continue to exist. However, the participants in this study did not describe curtailing participation because of these responses, rather they enacted advocacy, education and/or information gathering strategies to address these attitudes and barriers they encountered.

Individual ascription to the source of disability for participants was on a continuum, anchored at one end with a belief system that society disables individuals through environmental barriers and exclusionary practices,35 and at the other end, attributing their own physical impairments as the barrier to participation. Although most of the participants did not hold extreme views, those with childhood and adolescent experiences of living with a SCI seemed more inclined to hold a social model of disability perspective than those who had experienced their injury as an adult. This variation in perspective has been previously reported in a study of 1356 individuals with cervical SCI in France, in which only one-third of participants felt that most environmental difficulties could be addressed through social or political action.33 It may be that the biographical disruption32, 36 in an individual’s life course created by an acute SCI influences this perspective, as those with an acute SCI experienced immersion in a bio-medical model of rehabilitation following injury that those with a lifetime experience of SCI did not.

Implications for practice

The grounded theory of self-perceived participation among individuals with SCI developed provides a framework for clinical application. As rehabilitation professionals, it is important to know what to work toward to promote, facilitate and enhance participation among individuals with SCI. Understanding participation as an experience given meaning through selected activities and roles will help in the crucial conversations service providers have with individuals who are living in a changed world. Rehabilitation professionals should seek to understand what participation means to their clients and explore their individual experience of participation, rather than relying solely on society-perceived measures. Rehabilitation professionals working with individuals after SCI can view their role in terms of enabling the individual to address the body–environment interface through discussion on the relevance of each of the strategies identified by participants in this study, and supporting development of these strategies as led by the individual.

Furthermore, those working with individuals after SCI must recognize the transactive nature of the individual and environment. As stated by Fougeyrollas et al.29 ‘the environment cannot be considered as an accessory or an added piece of information that can be taken into account after the active process of rehabilitation is completed’. Service providers have a responsibility to influence the intervening conditions at a societal level to create opportunity for participation. By working in collaboration with individuals with SCI, service providers can continue to address environmental barriers to participation. For example, service providers can advocate for improved community accessibility, promote the development of respectful and transparent policy and increase societal awareness of environmental barriers to participation.

Dijkers37 reminds us that ‘(p)articipation is a key outcome of rehabilitation and of other medical and social service programs.’ Consequently, substantial effort is currently being directed toward conceptualizing and measuring participation. However, constructing only society-perceived perceptions of participation is an ‘injustice to the values and goals of the person served’.38 It is clear that the self-perceived aspect of participation should not be excluded from this discourse.

Although several studies have identified barriers to, or explored influencing factors on, participation among individuals with SCI, most have used a lens of society-perceived participation. This grounded theory study sought to understand participation, as defined by the participants with SCI. By elucidating the strategies used by individuals to engage in a process of participation, and highlighting the factors that promote and prevent participation; we position ourselves to better support the full inclusion and participation of individuals with SCI, supporting efforts of working toward development of a more inclusive society.

Limitations

Despite the fact that the findings did not demonstrate age- or gender-related differences, with a larger sample size, some of these differences may become evident. Future studies could examine self-perceived participation among a narrower age range, or among one gender, to better understand how these aspects might influence the perspective of participation. All participants were of European descent and thus future studies should seek to gain insight into the perspectives of those with different ethnic backgrounds. Data were collected over a relatively short period, and thus does not represent participation experiences across the disability trajectory of these participants. By conducting longitudinal studies, knowledge of the process of participation for adults with SCI over time could be developed. Theoretical sampling in this study led to the inclusion of several participants who had sustained their SCI in infancy. The experiences shared by these participants had nuances that provided some different dimensions from others who had sustained their injury as adults. Repeating this study with individuals who held different experiences of disability than of those who share the common experience of sudden SCI as an adult, would help clarify the role these different experiences play.

References

Rick Hansen Institute and Urban Futures The incidence and prevalence of spinal cord injury in Canada: overview and estimates based on current evidence. Retrieved 23 February 2011 from http://www.urbanfutures.com/reports/Report%2080.pdf2010.

Cardol M, De Jong BA, Ward CD . On autonomy and participation in rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil 2002; 24: 970–974.

Noreau L, Fougeyrollas P, Boschen KA . Participation after spinal cord injury: the evolution of conceptualization and measurement. JNeurol Phys Ther 2005; 29: 147–156.

Cicerone KD . Participation as an outcome of traumatic brain injury rehabilitation. J Head Trauma Rehabil 2004; 19: 494–501.

Dijkers MPJM, Whiteneck G, El-Jaroudi R . Measures of social outcomes in disability research. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2000; 81: S63–S80.

Hammel J, Jones R, Gossett A, Morgan E . Examining barriers and supports to community living and participation after a stroke from a participatory action research approach. Top Stroke Rehabil 2006; 13: 43–58.

World Health Organization International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF). Retrieved on 8 March 2011 from http://apps.who.int/classifications/icfbrowser/2001.

Carpenter C, Forwell SJ, Jongbloed LE, Backman CL . Community participation after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2007; 88: 427–433.

Harris F . Conceptual issues in the measurement of participation among wheeled mobility device users. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol 2007; 2: 137–148.

Anderson CJ, Vogel LC, Betz RR, Willis KM . Overview of adult outcomes in pediatric-onset spinal cord injuries: implications for transition to adulthood. J Spinal Cord Med 2004; 17 (Suppl 1): S98–S106.

Lund ML, Nordlund A, Bernspång B, Lexell J . Perceived participation and problems in participation are determinants of life satisfaction in people with spinal cord injury. Disabil Rehabil 2007; 29: 1417–1422.

Whiteneck G, Meade MA, Dijkers M, Tate DG, Bushnik T, Forchheimer MB . Environmental factors and their role in participation and life satisfaction after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2004; 85: 1793–1803.

Lysack C, Komanecky M, Kabel A, Cross K, Neufeld S . Environmental factors and their role in community integration after spinal cord injury. Can J Occup Ther 2007; 74: 243–254.

Ward K, Mitchell J, Price P . Occupation-based practice and its relationship to social and occupational participation in adults with spinal cord injury. OTJR 2007; 27: 149–156.

Van de Velde D, Bracke P, Van Hove G, Josephsson S, Vanderstraeten G . Perceived participation, experiences from persons with spinal cord injury in their transition period from hospital to home. Int J Rehab Res 2010; 33: 346–355.

Newman SD . Evidence-based advocacy: using photovoice to identify barriers and facilitators to community participation after spinal cord injury. Rehabil Nurs 2010; 35: 47–59.

Hammel J, Magasi S, Heinemann A, Whiteneck G, Bogner J, Rodriguez E . What does participation mean? An insider perspective from people with disabilities. Disabil Rehabil 2008; 30: 1445–1460.

Dietz ML, Prus RC, Shaffir W . Doing Everyday Life: Ethnography as Human Lived Experience. Copp Clark Longman Ltd.: Missisauga, ON. 1994.

Prus R . Symbolic Interaction and Ethnographic Research: Intersubjectivity and the Study of Human Lived Experience. State University of New York Press: Albany, NY. 1996.

Charmaz K . Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis. SAGE Publications: Los Angeles. 2006.

Wang C, Burris MA . Photovoice: Concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Educ Behav 1997; 24: 369–387.

Dahan R, Dick R, Moll S, Salwach E, Sherman D, Vengris J et al Photovoice Hamilton 2007: Manual and resource kit 2007. http://photovoice.ca/manual.pdf.

Law M, MacDermid J . Evidence-Based Rehabilitation: A Guide to Practice. SLACK Incorporated: Thorofare. 2008.

Burbank PM, Martins D . Symbolic interactionism and critical perspective: divergent or synergistic? Nurs Philos 2009; 11: 25–41.

Brown M . Participation: the insider’s perspective. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2010; 91: S34–S37.

van de Ven L, Post M, de Witte L, van den Heuvel W . Strategies for autonomy used by people with cervical spinal cord injury: a qualitative study. Disabil Rehabil 2008; 30: 249–260.

van de Ven L, Post M, de Witte L, van den Heuvel W . It takes two to tango: The integration of people with disabilities into society. Disabil Soc 2005; 20: 311–329.

Boschen KA, Tonack M, Gargaro J . Long-term adjustment and community reintegration following spinal cord injury. Int J Rehab Res 2003; 26: 157–164.

Fougeyrollas P, Noreau L, Boschen KA . Interaction of environment with individual characteristics and social participation: theoretical perspectives and applications in persons with spinal cord injury. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil 2002; 7: 1–16.

Corbin J, Strauss A . Accompaniments of chronic illness: changes in body, self, biography, and biographical time. Res Sociol Health Care 1987; 6: 249–281.

Wee J, Paterson M . Exploring how factors impact the activities and participation of persons with disability: constructing a model through grounded theory. Qual Rep 2009; 14: 165–200.

Hammell KW . Quality of life after spinal cord injury: a meta-synthesis of qualitative findings. Spinal Cord 2007; 45: 124–139.

Ville I, Crost M, Ravaud JF . Disability and a sense of community belonging a study among tetraplegic spinal-cord-injured persons in France. Soc Sci Med 2003; 56: 321–332.

Semple K, Blowes B, Seggles E, Baptiste S . Inclusive environments: The role of occupational therapy. Occup Ther Now 2010; 12: 16–18.

Oliver M . Theories in health care and research: theories of disability in health practice and research. Br Med J 1998; 317: 1446–1449.

Bury M . Chronic illness as biographical disruption. Sociol Health Illness 1982; 4: 167–182.

Dijkers MP . Issues in the conceptualization and measurement of participation: An overview. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2010; 91: S5–S16.

Brown M, Dijkers MPJM, Gordon WA, Ashman T, Charatz H, Cheng Z . Participation objective, participation subjective: a measure of participation combining outsider and insider perspectives. J Head Trauma Rehabil 2004; 19: 459–481.

Acknowledgements

The Canadian Occupational Therapy Foundation, the Senior Women Academic Administrators of Canada, the Canadian Federation of Women Alice E Wilson award and the University of Manitoba Graduate Students’ Association supported the first author. Drs Emily Etcheverry, Joannie Halas and Maria Medved provided support as part of the first authors’ graduate committee. We thank the 19 participants who generously gave their time and experiences for this study. Art Quanbury completed the required camera adaptations for participants. A research grant was received from the Canadian Paraplegic Association Spinal Cord injury Research Committee to conduct the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ripat, J., Woodgate, R. Self-perceived participation among adults with spinal cord injury: a grounded theory study. Spinal Cord 50, 908–914 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2012.77

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2012.77

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Participation and autonomy, independence in activities of daily living and upper extremity functioning in individuals with spinal cord injury

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

‘I Feel Free’: the Experience of a Peer Education Program with Fijians with Spinal Cord Injury

Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities (2018)

-

Spinal cord injury rehabilitation patient and physical therapist perspective: a pilot study

Spinal Cord Series and Cases (2016)

-

Navigating uncharted territory: a qualitative study of the experience of transitioning to wheelchair use among older adults and their care providers

BMC Geriatrics (2015)