Abstract

In 1985 Fridriech and Wintgen proposed a mechanism for bound states in the continuum based on full destructive interference of two resonances which can be easily applied to the two- and three-dimensional wave systems. Here we explicitly show that this mechanism can be realized in one-dimensional quantum potential well, owing to destructive interference of electron paths with different spin in tilted magnetic field. Due to one-by-one correspondence between the spin of the electron and the polarization state of light, we have found numerous bound states in the continuum in the one-dimensional photonic system and experimentally confirmed them. The experimental set-up consists of the one-dimensional photonic crystal conjugated with a liquid-crystalline anisotropic defect layer and covered by metal film.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In 1929, von Neumann and Wigner1 discovered that the long-range oscillating attractive one-dimensional (1D) potential can support localized solutions that correspond to isolated discrete eigenvalues embedded in the continuum of positive energy states. Extension and some correction of this work was done by Stillinger and Herrick2, who presented a few examples of attractive local potentials with bound states embedded in the continuum (BICs) of scattering states. The BIC is a classical paradox of a quantum particle with the energy enough to escape from the potential well and nevertheless remaining spatially confined. The BIC emerges due to precise destructive interference of waves scattered by a bound potential in such a way that, after enough distance, we obtain a localized state. The physics of localization is similar to Anderson localization in random potential3. However, the specially selected long-range bounded 1D potentials in refs. 1,2 have not been realized experimentally to consider the phenomenon of BICs as mathematical curiosity for a long time. In 1985, Friedrich and Wintgen4 in the framework of generic two-state effective non-Hermitian Hamiltonian formulated the concept of the BIC as the result of complete destructive interference of two resonances undergoing an avoided crossing. When two resonant states approach each other as a function of a certain continuous parameter, the width of one of them vanishes. Since the energy remains above the threshold for decay into the continuum, this state becomes a BIC although each resonant state has a finite width.

This concept was applied to two-dimensional plane microwave open resonator5 and two-dimensional photonic crystal (PhC) waveguide with two off-channel resonators6. In what follows, we define such a BIC as the Friedrich–Wintgen (FW) BIC. After the first experimental observation of the symmetry-protected (SP) BICs in two-dimensional PhC by Plotnik et al.7, the studies of BICs were intensively grown (see the review by Hsu et al.8). Recently, the BICs have found many applications, including sensing9, lasing10,11,12, terahertz magneto-optics13, photonic integrated circuits14, and topological photonics15,16,17,18,19,20. Although the individual dielectric resonator cannot support BIC, the concept of the avoided crossing of resonances is turned out to be very fruitful even with one or two subwavelength high-index dielectric resonators allowing to achieve resonant modes with high Q (quality) factor21,22,23,24.

When Maxwell’s equations are decoupled over transverse electric (TE) and transverse magnetic (TM) polarizations, they can be written in the form of the Helmholtz equations25 to result in one-by-one equivalence with quantum mechanics26. Therefore, layered one-dimensional PhC is equivalent to the 1D quantum mechanical problem with a stepwise potential profile for each polarization. However, in the 1D quantum mechanics with an arbitrary bounded potential, there are no transmittance zeros27, and respectively there are no FW BICs because of the absence of degeneracy and thereby of avoided crossing of resonances, which could result in the complete destructive interference. Thus, in the 1D-layered PhC structure, FW BICs cannot occur if the polarizations can be separated. However, if the PhC structure holds a defect layer that mixes polarizations of light, the FW BICs can occur because of complete destructive interference of two channels with different polarizations in the defect layer28,29,30. Similar FW BICs were also reported in a dielectric slab on a surface31, 1D solid–fluid phononic crystal32, and elastic layer in liquid33.

In this paper, we show that BICs occur even in 1D quantum well potential owing to destructive interference of electron paths with different spin in a tilted magnetic field. Moreover, due to the one-by-one correspondence between the spin of the electron and the polarization of light, we report numerous BICs in the one-dimensional PhC structure with anisotropic defect layer (ADL) that plays a role of the quantum well with a tilted magnetic field. In the experimental setup, the ADL is presented by liquid-crystalline anisotropic defect layer. We propose to replace one of the PhC arms with a metallic mirror in order to facilitate fabrication, decrease the structure size, and govern the BIC by external fields applied to liquid crystal. In the reflectance spectra, we show numerous events of the Fano resonance collapse34, which unambiguously witness the FW BICs. Thus, the 1D-layered structures pave the way to novel tunable high-quality devices both in spintronics and photonics.

Results

Friedrich–Wintgen BICs in a one-dimensional spin model

Due to the one-by-one correspondence between the spin of the electron and the polarization state of light (Table 1),

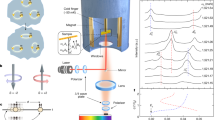

we illustrate the one-dimensional FW BICs first in a toy quantum model of spin-polarized electron transmission. Let us consider three domains in which the external stationary magnetic field is applied as sketched in Fig. 1a. Assume that the external magnetic field B inside the central layer is tilted relative to the x-oriented outer magnetic field. We also assume that the inner layer has the potential shifted relative to the outer layers by a value U0. Outside of the central layer, an electron has two split-energy spectra \(E={k}_{\sigma }^{2}\mp B\), σ = ↑, ↓ which specify the continua by the wave vector kσ. In the central layer, the spin-dependent spectra have the following form \(E={k}_{s}^{2}+{U}_{0}\mp B,\ s=1,2\) which specifies spin-dependent channels by the vector ks. The energy band structure is given in Supplementary Note 1. Owing to the choice of the potential step (U0 = −20) as depicted in Fig. 1a by green, both spin channels are open in the central layer, while outside only the spin-up continuum is open for E < B. Therefore, only the electron with spin up can transmit and reflect by the central layer. The solution of the scattering problem is given in Supplementary Note 2.

a Beyond the central layer, the magnetic field B is directed along the x axis, inside the central layer B that is tilted by angle ϕ. The spin-up electron falls by angle θ with the energy below the spectrum of spin-down and splits into two channels specified by k1 and k2. b Reflectance of the spin-up electron for B = 10 tilted by angle ϕ = π/4 and U0 = −20, vs incident energy E and central layer thickness L at angle of incidence θ = π/3. Magenta pluses mark the BIC solutions symmetric with respect to the center of the layer, while crosses mark the antisymmetric BICs. The wave function ψ for both symmetric and antisymmetric BIC solutions is plotted in (c). d Reflectance of the spin-up electron for B = 10 tilted by angle ϕ = π/4 and U0 = −20 vs angle of incidence θ and central layer thickness L at incident energy E = 30.

Figure 1b shows the electron reflectance in dependence on energy E. One can see numerous points of collapse of Fano resonances that are the unambiguous signatures of the BICs5,34. These points coincide with the analytic solutions for the BICs as the solution that has zero coupling with the spin-up continuum, but is coupled with the evanescent spin-down channel. These conditions and the corresponding equations for the BICs are presented in Supplementary Note 2, and two examples of the solutions are shown in Fig. 1c. Similarly, the numerous Fano resonance collapses appear for dependencies on such parameter as the angle of incidence θ (Fig. 1d).

Friedrich–Wintgen BICs in a one-dimensional photonic model

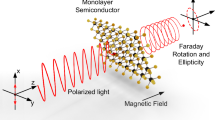

Although this spin model cannot be directly applied for electrons because of neglecting the orbital motion of electrons in the magnetic field, it has one-by-one correspondence to the polarized light reflection from an anisotropic defect layer (ADL). The aim of this paper is realization of the FW BICs in the optical analog of the spin model, in a 1D-layered PhC structure where the TE and TM polarizations of the light play the role of spin up and -down, and the defect layer with optical anisotropy plays the role of the layer with a tilted magnetic field. What is more remarkably predicted is that FW BICs are certified experimentally.

There are also some differences between the spin model and its optical analog. First of all, there is no counterpart of Zeeman interaction in optics, which could split the frequency of light with different polarizations. Instead, we use the optical materials in which propagation bands are split by the polarization of light. In particular, one way is the use of anisotropic optical waveguides28,30,35. Another way is 1D-alternating PhC that supports continua specified by light polarization29 having close correspondence with the spin model. The ADL conjugated with two 1D PhC arms is equivalent to the central layer with the tilted magnetic field (see Fig. 2a), while the 1D- alternating PhC arms respond for the continua split by polarization as shown in Fig. 2b. Similar to the spin model, we expect that the FW BICs of superposed polarizations are embedded into the TM continua of the 1D PhC arms specified by wave number kx or angle of incidence θ.

a 1D photonic crystal (PhC) with the anistropic defect layer (ADL). Optical properties of the ADL are defined by refractive indices n⊥, n∥ and direction of the anisotropy axis (a). The transverse magnetic (TM)-polarized light is incident at Brewster's angle θB. Local intensity of the electric field distribution for the transverse electric (TE) (blue) and TM wave (red) near the FW BIC: asymmetric solution (ϕ = 53. 5°, λ = 568 nm) in (c). b Photonic band structure for TE (blue) and TM wave (red). The solid black line corresponds to Brewster's angle. Magenta pluses correspond to the symmetric analytical solutions for BICs; crosses correspond to the asymmetric solutions for ϕ = 0. c Numerical TM-polarized reflectance spectra vs anisotropy axis rotation angle ϕ. d Quality (Q) factor for one of the resonant curves in (c) containing FW BIC (ϕ = 52.4°, λ = 568 nm) (black). The Q factor for twice-reduced scheme (1D PhC conjugated with twice-thinner ADL), covered by a metal film with refractive index nM = 0.14 + 20i (magenta).

A fabrication of the 1D anisotropic PhC is technologically difficult because of the necessity to exploit highly anisotropic materials. The exploitation of low-anisotropic material would increase the total number of layers, and elongate the structure, leading to fabrication inaccuracies. Here we suggest a different fabrication-friendly photonic structure for observing FW BICs. In order to split the propagation bands into the polarization of light outside the ADL, we use semi-infinite 1D PhC arms (Fig. 2a) composed of alternating isotropic layers A and B with refractive indices na and nb and thicknesses da and db. The polarization-dependent band structure in these 1D PhC arms is given in Supplementary Note 3 and shown in Fig. 2b.

The 1D PhC arms are conjugated with the uniaxial ADL with thickness L. The optical properties of the ADL are determined by the longitudinal n∥ and transverse n⊥ refractive indices with the unit vector of the direction of the optical axis \({\bf{a}}=(\sin (\phi ),\cos (\phi ),0)\). In Fig. 2b, the TM continuum (shown by red) is open with the appropriate choice of kx, while the TE continuum (shown by blue) is closed. Similar to the layer with a tilted magnetic field in the spin model, the ADL supports two orthogonal eigenmodes whose polarization vectors are tilted relative to the polarization vector of TM-wave light propagating in the 1D PhC arm. These modes can also be identified as the ADL channels. As a result, we obtain the one-by-one correspondence between the spin toy model in Fig. 1a and the present photonic system as illustrated in Table 1.

If a TM plane wave ei(kr−ωt) is injected, both eigenmodes of the ADL become observable as resonances in the TM reflectance spectra. Here wave vector k = (kx, 0, kz) and kx is fitted into the propagation band of the 1D PhC shown by red in Fig. 2b. Figure 2c demonstrates how the reflectance depends on wavelength and anisotropy axis tilt ϕ. Similar to the spin model, one can plot the dependencies on the angle of incidence θ and the ADL thickness L. Both analytical and numerical routines are presented in Supplementary Notes 3, 4 and “Methods”. Under variation of the parameters (Fig. 2c), the resonant width turns to zero similar to the spin behavior shown in Figs. 1b,d. Thereby, we realize the FW BICs with zero resonant widths as the result of complete destructive interference of TE and TM polarizations. The BICs are decoupled from the continua of the 1D PhC arms. The coupling can be easily tuned by rotating the optical axis given by the azimuthal angle ϕ. In this study, we observe two types of BICs: SP (at ϕ = 0, 90°) and nontrivial FW BICs (at ϕ ≠ 0, 90°). The value of the Q factor is plotted in Fig. 2d. Three BICs correspond to the infinite Q factor.

Experimental realization of Friedrich–Wintgen BICs

For experimental verification, the model was modified to facilitate fabrication and measurement (Fig. 3a) where the right 1D PhC arm was replaced by a gold mirror film with refractive index nM (thickness = 300 nm). The left 1D PhC arm consists of eight pairs of SiO2 (da = 145 nm) and TiO2 (db = 94 nm) layers. The ADL with length d = L/2 = 1.375 μm is filled by planar-aligned E7 nematic liquid crystal. Such a setup allows us to eliminate the right 1D PhC and optical prism collimating the light beam at the right of ADL, and control the angle ϕ of the anisotropy axis of the ADL through the voltage applied to the gold film. That setup brings unnecessary material losses in metals and sets the limit to the Q factor as shown in Fig. 2d even for low-loss metal. The number of BICs with the metal mirror case (Figs. 3b, 4a) is two times less than that in the symmetric setup (Fig. 2c). It stems from the fact that the metal mirror can support only anti-symmetric solutions in the ADL. In the case of the ideal metal mirror (nM = i∞), the electric field has its node at the interface.

a 1D photonic crystal (PhC) conjugated with the anisotropic defect layer (ADL) and a metallic mirror. Local intensity of the electric field distribution for the transverse electric (TE) (blue) and transverse magnetic (TM) wave (red) near the FW BIC: asymmetric solution (ϕ = 50.6°, λ = 573.6 nm) in (b). b Numerical TM-polarized reflectance spectra vs anisotropy axis rotation angle ϕ for structures depicted in (a) with low-loss metal (refractive index nM = 0.14 + 20i). Magenta crosses correspond to the asymmetric solutions for BICs.

A vivid example of the difference in the 1D PhC band structures for the TE- and TM waves is the presence of a certain wave propagation direction in which the photonic bandgaps for the TM waves vanish at the Brewster’s angle36. In Fig. 2b, the Brewster’s direction is shown by the black solid line. In this situation, the angles of propagation in alternating layers A and B satisfy the relation θa + θb = π/2, where \({\theta }_{{\rm{a}}}=\arctan ({n}_{{\rm{b}}}/{n}_{{\rm{a}}})\). The radiation was introduced into the structure using a glass lens to implement the Brewster’s effect for the 1D PhC arm. The sample was mechanically rotated to change the tilt angle ϕ of the optical axis relative to the plane of incidence. The measured reflectance spectra of the structure are presented in Fig. 4a, b right panel. The details of sample preparation and measurement techniques are presented in Methods. For comparison, the results of the numerical calculation with the Berreman matrix method37 are shown in Fig. 4a, b left panel.

a Experimental (right panel) and numerical (left panel) transverse magnetic (TM)-polarized reflectance spectra vs liquid-crystal anisotropy axis rotation angle ϕ. Magenta crosses correspond to the asymmetric analytical solutions for BICs and experimental points of resonance collapse. b Spectral branch shows one FW and another symmetry-protected BIC. The blue dashed line shows the analytical dispersion curve for the transverse electric (TE)-polarized microcavity mode. c Experimental (dashed line) and numerical (solid line) TE-polarized reflectance spectra present no resonances.

There are no resonances in the TE-polarized spectra (Fig. 4c), indicating that the TE continuum is closed. The position and width of the resonances corresponding to microcavity modes in the TM spectra (Fig. 4a) depend on the angle ϕ. The blue shift of the wavelength of the microcavity mode localized in the ADL is qualitatively explained by a decrease in the effective refractive index nd of the ADL and consequently by its optical thickness. Under variation of the angle of the optical axis in the range of 0° ≤ ϕ ≤ 90°, the effective refractive index of the ADL for the electric component Ey of the localized TE mode takes the values between n∥ ≥ nd ≥ n⊥.

The change in the spectral width of the microcavity mode is caused by the change in the coupling between the TE-polarized localized mode (the analog of the state with \(\left|\downarrow \right\rangle\)) and the TM-polarized continuum (the analog of the state \(\left|\uparrow \right\rangle\)) through the mixing of the polarizations in the ADL. The situation is qualitatively explained by the fact that, in the general case, in the ADL upon rotation of the optical axis a, there exist two types of eigensolutions: the extraordinary (e) (the analog of the state \(\left|2\right\rangle\)) and ordinary (o) (the analog of the state \(\left|1\right\rangle\)) waves. The electric field vectors of the e- and o waves are mutually orthogonal ((Eea) ≠ 0, (Eoa) = 0) and, generally, make the nonzero contributions to the TE- and TM waves, thereby ensuring the coupling between them. One can see from the spectra that at certain values of the parameters, the resonance collapses that is an unambiguous signature of the BIC.

The collapse of the resonance mode width at ϕ = 0° and ϕ = 90° indicates the existence of the SP BICs. At ϕ = 0°, the ADL optical axis a = (0, 1, 0) is oriented along the y axis, and the localized TE mode with the electric field component Ey excites the e wave with the electric field vector directed along the y axis and does not contribute to the continuum of the propagating TM waves. Inversely, the propagating TM wave with the electric field component Ex excites only the o wave in the ADL, the electric field vector of which is directed along the x axis and does not contribute to the localized TE mode. Thus, the localized TE mode is decoupled to the continuum of the TM waves; it can be neither excited through the continuum nor decays into it, since the coupling between the localized mode and the continuum turns to zero. Similarly, at ϕ = 90°, the optical axis a = (1, 0, 0) of the anisotropic layer is oriented along the x axis, so the e wave makes the nonzero contribution to the TM-wave only, and the o wave contributes to the TE-mode only.

The collapse of the resonant mode width in the experimental spectra at ϕ = 55° and ϕ = 40° evidences for the existence of the FW BICs as shown in Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 8. The occurrence of the FW BIC is explained by complete destructive interference of the e- and o waves at the output from the ADL. The rotation of the ADL optical axis a, which is analogous to the rotation of the direction of the magnetic field, changes the absolute value and direction of the e-wave vector ke = ke(ϕ), as well as the electric fields Ee = Ee(ϕ) and Eo = Eo(ϕ) of both the e- and o waves. As a result, at certain angle ϕ at the ADL output (at z = d), the conditions Eey + Eoy ≠ 0 and Eex + Eox = 0 are satisfied. The contribution to the TE mode is nonzero, and that to the propagating TM wave turns to zero, i.e., the resonant mode becomes a BIC again.

The field distributions for the TE- and TM-polarized waves near the FW BIC are shown in Figs. 2a and 3a. One can see that the localized field near the FW BIC has both TE- and TM components, in contrast to the TE-polarized SP BIC. It is worth noting that, in contrast to the SP BICs, which exist for every resonant branch at ϕ = 0° and 90° only, the number and position of the FW BICs may be arbitrarily tuned. This depends not only on the angle ϕ of rotation of the optical axis, but also on the thickness d and anisotropy n∥/n⊥ of the ADL.

For the qualitative description, we analytically solved the eigenvalue problem with reflectionless boundary conditions, and found the dispersion equation for the microcavity modes (Supplementary Note 4). The solution has a complex eigenfrequency ω = ωr + iγ, meaning that the corresponding microcavity mode has the spectral position λr = 2π/ωr and the quality factor Q = ωr/2γ. The analytical dispersion curves λr(ϕ) fit well with the experimental and numerical spectra (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Figs. 2, 4, 9). The Q factor of the resonant mode is determined by two components: the material loss 1/QM, which is the absorption of light by the metallic layer, and the TE-mode leakage into the continuum of TM waves 1/Q(ϕ): 1/Q = 1/QM + 1/Q(ϕ). At 1/Q(ϕ) = 0, the total Q factor is limited by the material loss. The experimental Q factors were found to be lower by an order of magnitude in comparison with the theoretical Q factor limited by QM (see Supplementary Fig. 10). The reason is the liquid-crystal layer thickness variation, which can potentially be eliminated by replacing liquid ADL by metasurface38,39,40,41 at the price of tunability.

It should be noted that for the normal incidence29, the FW BICs are described by relation 2d(ke − ko) = 2πm. Physically, it means that the FW BICs occur when the ADL acts as a full-wave phase plate42. The TE-polarized light incident onto such a full-wave phase plate preserves its original polarization at the layer output, without being converted into the continuum of the orthogonal TM waves. To the best of our knowledge, the FW BICs in a 1D PhC-layered structure were experimentally observed in this study for the first time.

Discussion

The proposed scheme has an important advantage over the previous schemes of BIC observation in layered media28,29,30, it requires the only one 1D PhC arm and a defect layer holding a liquid-crystal cell. In addition, the Brewster’s angle is less than the angle of total internal reflection28,30, providing easier excitation and increased confinement of the radiation. The sensitivity of a liquid crystal to external influence43,44,45 allows one to control the coupling between the continuum and localized modes by heating or application of electric or magnetic fields.

A decrease in the ADL thickness leads to the reduction of the number of leaky bands up to the single one. In the last case, we face with Tamm plasmon–polariton46,47 widely used in photonics and optoelectronics48,49, as an optical analog of the electronic Tamm state in condensed matter physics50. The Tamm state is transformed into the BIC in the present setup 1DPhC arm+ADL+metal when the ADL is sufficiently thin.

Owing to the one-by-one equivalence between quantum mechanics and optics, the Brewster-tilted BICs have been observed experimentally in the 1D PhC with a defect anisotropic layer. The possibility of controlling of the Q factor of the quasi-BIC modes is demonstrated by rotating the optical axis of the liquid crystal. One can use an all-dielectric structure 1D PhC arm+ADL+1D PhC (Fig. 1a) in order to diagnose BIC with an extremely high Q factor. We propose to replace one of the PhC arms with a metallic mirror in order to facilitate fabrication, decrease the structure size, and govern the BIC by external fields applied to liquid crystal. The experimental data obtained from reflectance spectra of E7-liquid-crystal cell placed between a PhC and a gold mirror are in good agreement with the theoretical and numerical results. We underline that the 1D-layered structures pave the way to novel tunable high-quality devices both in spintronics and photonics.

Methods

Berreman’s transfer-matrix method

To calculate the reflection spectra of the layered structure, the transfer-matrix method is used, which is generalized by Berreman to anisotropic media37, a detailed description of which is given in ref. 42. The system of Maxwell’s equations is written in the form of wave equation for the 4 × 1 vector field amplitudes \({\bf{J}}={({E}_{x},{H}_{y},{E}_{y},-{H}_{x})}^{T}\)

where \(\hat{\Delta }\) is a differential matrix of propagation whose elements are expressed in terms of elements of the permittivity tensor. If the permittivity tensor does not depend on z within the jth layer with a thickness of dj, then integration (1) gives a connection of fields on the right (z = zj + dj) and the left (z = zj) boundaries of the layer: \({\bf{J}}({z}_{j}+{d}_{j})={\hat{L}}_{j}{\bf{J}}({z}_{j})\), \({\hat{L}}_{j}={e}^{i{k}_{0}{d}_{j}{\hat{\Delta }}_{j}}\). That allows to relate fields at the entrance to the fields at the first layer of the structure and further to the exit from the last, Nth layer, in the form

The field on the left boundary of the structure can be represented as a sum of the incident and reflected waves J(z1) = Ji(z1) + Jr(z1); the field on the right boundary is the field of the transmitted wave \({\bf{J}}({z}_{1}+\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{j = 1}^{N}{d}_{j})={{\bf{J}}}_{{\rm{t}}}({z}_{1}+\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{j = 1}^{N}{d}_{j})\). Substituting these boundary conditions into (2), we link the amplitudes Ji, Jr, Jt. After that, reflection coefficients Rs,s, Rs,p, Rp,p, Rp,s are naturally expressed, as well as transmission coefficients Ts,s, Ts,p, Tp,p, Tp,s through the elements of the matrix \(\hat{{\mathscr{L}}}\). The s index corresponds to the TE wave, and the p index corresponds to the TM wave. The Berreman’s method is implemented in the MATLAB software (license # 984723).

Finite-difference time-domain method

To simulate the Brewster-tilted BIC resonance with tunable Q factors, the Finite-difference time-domain (FDTD, Lumerical) method51 is used. In the modeling, the BIC structure includes the substrate, PhC, alignment layer, anisotropic layer, and the gold layer. The refractive indices of the anisotropic layer are set to (x, y, z) = (no, no, ne). Boundary conditions (BCs) in the form of the perfectly matching layers (PML) are set in the y direction, and the Bloch boundaries are set in the x direction. The Bloch BCs allow us to find the solution of the entire system by simulating the one- unit cell by a phase shift of the fields. The source of the plane wave is illuminated from the substrate in the Brewster angle (53.13°). The monitor of frequency-domain fields and power is used to calculate the reflectance spectrum of the structure. The schematic diagram of FDTD simulation is given in Supplementary Fig. 5.

Calculation parameters

To calculate the band structure, dispersion curves and reflectance spectra of the finite structure, frequency-dependent refractive indices for gold (Aurum) (nM = nAu)52, silicon dioxide (\({n}_{{\rm{a}}}={n}_{{{\rm{SiO}}}_{2}}\))53, titanium dioxide (\({n}_{{\rm{b}}}={n}_{{{\rm{TiO}}}_{2}}\))54, E7 liquid-crystal mixture (n⊥,∥ = no, eE7)55,56, and poly(methyl methacrylate) (nc = nPMMA)57 were used. The tangent component of the wave vector is \({k}_{x}={n}_{{\rm{in}}}{k}_{0}\sin ({\theta }_{{\rm{in}}})\), where the RI of the prism is nin = 1.52 and the angle of incidence in the prism satisfies the Brewster condition for the PhC \({\theta }_{{\rm{in}}}={\theta }_{{\rm{B}}}=\arcsin (({n}_{{\rm{b}}}/{n}_{{\rm{in}}})\sin ({\theta }_{{\rm{b}}}))\approx 53.{1}^{\circ }\). The geometrical parameters of the layers used for the calculation correspond to the real structure described in the “Experimental setup” section. To obtain the realistic Q-factor and reflection spectra, the simulated spectra were averaged over the E7-layer thicknesses ±10 nm.

Experimental setup: fabrication and measurements

To fabricate the BIC sample, the gold film (thickness = 300 nm) and the PhC (8 pairs of SiO2 (da = 145 nm) and TiO2 (db = 94 nm)) are deposited on two substrates separately. Polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) (dc = 200 nm) is spin-coated on the PhC as the alignment layer. In order to make a smaller gap, the plano-convex curvature substrate (f = 5000 mm) is used for the gold film. Then, the optical fixture is used to clamp the two substrates, and the Newton’s ring will appear and make the cell gap (~1.375 μm) in the structure. Then, the anisotropic material (liquid crystal E7) is filled into the small gap. The schematic diagram of the experimental sample is given in Supplementary Fig. 6. In characterization, the Brewster-titled spectral measurement system is set up. The excitation light source is a halogen lamp. The light incidents from the prism in the Brewster angle. The pinhole (aperture stop) is used to control beam size, and the linear polarizer is used to set the polarization state (TE or TM). The sample can be rotated in azimuthal angles to measure reflectance spectra from ϕ = 0° to ϕ = 180° with the Brewster-angle incident cone. The schematic diagram of the experimental setup is given in Supplementary Fig. 7.

Data availability

All essential data are available in the paper and Supplementary Information. Further supporting data can be provided from the corresponding author upon request.

References

von Neumann, J. & Wigner, E. P. Über merkwürdige diskrete Eigenwerte. Z. Phys. 30, 465–467 (1929).

Stillinger, F. H. & Herrick, D. R. Bound states in the continuum. Phys. Rev. A 11, 446–454 (1975).

Anderson, P. W. Absence of diffusion in certain random lattices. Phys. Rev. 109, 1492–1505 (1958).

Friedrich, H. & Wintgen, D. Interfering resonances and bound states in the continuum. Phys. Rev. A 32, 3231–3242 (1985).

Sadreev, A. F., Bulgakov, E. N. & Rotter, I. Bound states in the continuum in open quantum billiards with a variable shape. Phys. Rev. B 73, 235342 (2006).

Bulgakov, E. N. & Sadreev, A. F. Bound states in the continuum in photonic waveguides inspired by defects. Phys. Rev. B 78, 75105 (2008).

Plotnik, Y. et al. Experimental observation of optical bound states in the continuum. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 28–31 (2011).

Hsu, C. W., Zhen, B., Stone, A. D., Joannopoulos, J. D. & Soljačić, M. Bound states in the continuum. Nat. Rev. Mater. 1, 16048 (2016).

Romano, S. et al. Tuning the exponential sensitivity of a bound-state-in-continuum optical sensor. Opt. Express 27, 18776–18786 (2019).

Kodigala, A. et al. Lasing action from photonic bound states in continuum. Nature 541, 196–199 (2017).

Song, Y., Jiang, N., Liu, L., Hu, X. & Zi, J. Cherenkov radiation from photonic bound states in the continuum: towards compact free-electron lasers. Phys. Rev. Appl. 10, 64026 (2018).

Huang, C. et al. Ultrafast control of vortex microlasers. Science 367, 1018–1021 (2020).

Chen, G. Y., Zhang, W. X. & Zhang, X. D. Strong terahertz magneto-optical phenomena based on quasi-bound states in the continuum and fano resonances. Opt. Express 27, 16449 (2019).

Yu, Z. et al. Photonic integrated circuits with bound states in the continuum. Optica 6, 1342 (2019).

Zhen, B., Hsu, C. W., Lu, L., Stone, A. D. & Soljačić, M. Topological nature of optical bound states in the continuum. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 257401 (2014).

Bulgakov, E. N. & Maksimov, D. N. Topological bound states in the continuum in arrays of dielectric spheres. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 267401 (2017).

Mukherjee, S., Gomis-Bresco, J., Pujol-Closa, P., Artigas, D. & Torner, L. Topological properties of bound states in the continuum in geometries with broken anisotropy symmetry. Phys. Rev. A 98, 063826 (2018).

Doeleman, H. M., Monticone, F., denHollander, W., Alù, A. & Koenderink, A. F. Experimental observation of a polarization vortex at an optical bound state in the continuum. Nat. Photonics 12, 397 (2018).

Liu, W. et al. Circularly polarized states spawning from bound states in the continuum. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 116104 (2019).

Jin, J. et al. Topologically enabled ultrahigh-q guided resonances robust to out-of-plane scattering. Nature 574, 501–504 (2019).

Wiersig, J. Formation of long-lived, scarlike modes near avoided resonance crossings in optical microcavities. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 253901 (2006).

Rybin, M. V. et al. High-Q supercavity modes in subwavelength dielectric resonators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 243901 (2017).

Chen, M., Jiang, L. & Sha, W. Orbital angular momentum generation and detection by geometric-phase based metasurfaces. Appl. Sci. 8, 362 (2018).

Pichugin, K. N. & Sadreev, A. F. Interaction between coaxial dielectric disks enhances the Q factor. J. Appl. Phys. 126, 093105 (2019).

Jackson, J.D. Classical Electrodynamics 3 edn. (Wiley Inc., New York, 1998).

Joannopoulos, J.D., Johnson, S.G., Winn, J.N. & Meade, R.D. Photonic Crystals: Molding the Flow of Light 2nd edn (Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, 2008).

Lee, H.-W. Generic transmission zeros and in-phase resonances in time-reversal symmetric single channel transport. Phys. Rev. Lett. 82, 2358–2361 (1999).

Gomis-Bresco, J., Artigas, D. & Torner, L. Anisotropy-induced photonic bound states in the continuum. Nat. Photonics 11, 232–236 (2017).

Timofeev, I. V., Maksimov, D. N. & Sadreev, A. F. Optical defect mode with tunable Q factor in a one-dimensional anisotropic photonic crystal. Phys. Rev. B 97, 24306 (2018).

Mukherjee, S., Gomis-Bresco, J., Pujol-Closa, P., Artigas, D. & Torner, L. Angular control of anisotropy-induced bound states in the continuum. Opt. Lett. 44, 5362 (2019).

Bezus, E. A., Bykov, D. A. & Doskolovich, L. L. Bound states in the continuum and high-Q resonances supported by a dielectric ridge on a slab waveguide. Photonics Res. 6, 1084–1093 (2018).

Quotane, I., ElBoudouti, E. H. & Djafari-Rouhani, B. Trapped-mode-induced Fano resonance and acoustical transparency in a one-dimensional solid-fluid phononic crystal. Phys. Rev. B 97, 024304 (2018).

Mizuno, S. Fano resonances and bound states in the continuum in a simple phononic system. Appl. Phys. Express 12, 35504 (2019).

Kim, C. S., Satanin, A. M., Joe, Y. S. & Cosby, R. M. Resonant tunneling in a quantum waveguide: effect of a finite-size attractive impurity. Phys. Rev. B 60, 10962 (1999).

Razzaz, F. & Alkanhal, M. A. S. Resonances in bianisotropic layers. IEEE Photonics J. 10, 1–12 (2017).

Born, M. & Wolf, E. Principles of Optics: Electromagnetic Theory of Propagation, Interference and Diffraction of Light (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1999).

Berreman, D. W. Optics in stratified and anisotropic media: 4 × 4-matrix formulation. J. Optical Soc. Am. 62, 502–510 (1972).

Glybovski, S. B., Tretyakov, S. A., Belov, P. A., Kivshar, Y. S. & Simovski, C. R. Metasurfaces: from microwaves to visible. Phys. Rep. 634, 1–72 (2016).

Jahani, S. & Jacob, Z. All-dielectric metamaterials. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 23 (2016).

Kildishev, A. V., Boltasseva, A. & Shalaev, V. M. Planar photonics with metasurfaces. Science 339, 1232009 (2013).

DellaValle, G. et al. Nonlinear anisotropic dielectric metasurfaces for ultrafast nanophotonics. ACS Photonics 4, 2129–2136 (2017).

Azzam, R.M.A. & Bashara, N.M. Ellipsometry and Polarized Light (North-Holland personal library, North-Holland Pub. Co., Amsterdam, 1977).

Arkhipkin, V. G. et al. One-dimensional photonic crystals with a planar oriented nematic layer: temperature and angular dependence of the spectra of defect modes. J. Exp. Theor. Phys. 106, 388–398 (2008).

Pankin, P. S., Vetrov, S. Y. & Timofeev, I. V. Tunable hybrid Tamm-microcavity states. JOSA B 34, 2633–2639 (2017).

Cheng, H.-C., Kuo, C.-Y., Hung, Y.-J., Chen, K.-P. & Jeng, S.-C. Liquid-crystal active tamm-plasmon devices. Phys. Rev. Appl. 9, 64034 (2018).

Vinogradov, A. P. et al. Surface state peculiarities in one-dimensional photonic crystal interfaces. Phys. Rev. B 74, 1–8 (2006).

Kaliteevski, M. et al. Tamm plasmon-polaritons: Possible electromagnetic states at the interface of a metal and a dielectric Bragg mirror. Phys. Rev. B 76, 165415 (2007).

Yang, Z.-Y. et al. Narrowband wavelength selective thermal emitters by confined tamm plasmon polaritons. ACS Photonics 4, 2212–2219 (2017).

Afinogenov, B. I., Bessonov, V. O., Nikulin, A. A. & Fedyanin, A. A. Observation of hybrid state of Tamm and surface plasmon-polaritons in one-dimensional photonic crystals. Appl. Phys. Lett. 103, 061112 (2013).

Tamm, I. On the possible bound states of electrons on a crystal surface. Phys. Z. Sowjetunion 1, 733–735 (1932).

Taflove, A. & Hagness, S.C.Computational Electrodynamics: The Finite-Difference Time-Domain Method (Artech house, Boston, London, 2005).

Johnson, P. B. & Christy, R. W. Optical constants of the noble metals. Phys. Rev. B 6, 4370–4379 (1972).

Gao, L., Lemarchand, F. & Lequime, M. Refractive index determination of SiO2 layer in the UV/Vis/NIR range: spectrophotometric reverse engineering on single and bi-layer designs. J. Eur. Opt. Soc.-Rapid. 8, 13010 (2013).

Siefke, T. et al. Materials pushing the application limits of wire grid polarizers further into the deep ultraviolet spectral range. Adv. Optical Mater. 4, 1780–1786 (2016).

Li, J., Wen, C.-H., Gauza, S., Lu, R. & Wu, S.-T. Refractive indices of for display applications. J. Disp. Technol. 1, 51–61 (2005).

Tkachenko, V. et al. Nematic liquid crystal optical dispersion in the visible-near infrared range. Mol. Cryst. Liq. Cryst. 454, 263–665 (2006).

Beadie, G., Brindza, M., Flynn, R. A., Rosenberg, A. & Shirk, J. S. Refractive index measurements of poly (methyl methacrylate)(PMMA) from 0.4–1.6 μm. Appl. Opt. 54, F139–F143 (2015).

Acknowledgements

The reported study was funded by Russian Foundation for Basic Research project Nos. 19-52-52006 and 19-02-00055. This project is also supported by the Higher Education Sprout Project of the National Chiao Tung University and Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST No. 107-2221-E-009-046-MY3; No. 108-2923-E-009-003-MY3). S.A.F. thanks RFBR for the research project No. 19-02-00055. The authors are thankful to D.N. Maksimov for valuable discussions and comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.I.V. and S.A.F. proposed the idea of BIC in 1D PhC. S.A.F. proposed and developed analytics for the spin model. P.S.P. developed analytics for the optical model. P.S.P. and T.I.V. performed Berreman’s method numerical simulations. W.B.R., J.H.Y. and K.P.C. fabricated the experimental samples and performed the spectral measurements. W.B.R. and J.H.Y. ran FDTD method simulations. T.I.V., K.P.C. and S.A.F. supervised the investigation. All authors proofread the paper, made comments, and approved the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pankin, P.S., Wu, BR., Yang, JH. et al. One-dimensional photonic bound states in the continuum. Commun Phys 3, 91 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-020-0353-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-020-0353-z

This article is cited by

-

Bound states in the continuum in anisotropic photonic crystal slabs

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Applications of bound states in the continuum in photonics

Nature Reviews Physics (2023)

-

Bound states in the continuum and Fano resonances in photonic and plasmonic loop structures

Optical and Quantum Electronics (2022)

-

Photonic bandgap engineering using second-order supersymmetry

Communications Physics (2021)

-

Polarization-selective modulation of supercavity resonances originating from bound states in the continuum

Communications Physics (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.