Abstract

Understanding the microscopic mechanism is fundamental for function-oriented controlled chemical vapor deposition growth of two-dimensional (2D) materials. In this work, we reveal the growth kinetics of 2D MoS2 by capturing the nucleation seeds, evolving morphology, edge structure, and edge terminations at the atomic scale during chemical vapor deposition growth using the transmission electron microscopy and scanning transmission electron microscopy. The direct growth of few-layer and mono-layer MoS2 onto graphene-based transmission electron microscopy grids helped us to perform the subsequent transmission electron microscopy characterization without any solution-based transfer. Two seeding centers are observed: (i) Mo-oxysulfide (MoO x S2−y ) nanoparticles either in multi-shelled fullerene-like structures or as compact nanocrystals for the growth of fewer-layer MoS2; (ii) Mo-S atomic clusters. In the early stage growth, irregular polygons with two primary edge terminations, S-Mo Klein edges and Mo zigzag edges, appear approximately in equal numbers. The morphology evolves into a near-triangle shape in which Mo zigzag edges predominate. Results from density-functional theory calculations are consistent with the inferred growth kinetics, and thus support the growth mechanism we proposed. In general, the growth mechanisms found here should also be applicable in other 2D materials, such as MoSe2, WS2 and WSe2.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Two-dimensional molybdenum disulfide (2D MoS2), a representative member of the rediscovered transition metal dichalcogenide (TMDC) family, holds promising interest owing to their excellent performance in electronic, optoelectronic, catalytic and bio applications.1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10 However, many challenges remain to be overcome in realizing the potential applications, for instance, the carrier type and concentration, i.e., equivalent good performance for both n-type and p-type in electronic devices, the structure/morphology, wafer-size sample and in high quality. Out of these, the controlled growth seems to be a key issue. So far, chemical vapor deposition (CVD), as one of the most successful routes, has been widely adopted to grow 2D material from graphene,11, 12 hexagonal boron nitride13 to 2D TMDC materials,14,15,16,17 while the growth mechanisms, particularly in the CVD growth of 2D TMDC materials, is still poorly understood.

Previous studies have successfully revealed the roles of a number of important parameters determining the CVD growth behaviors of 2D MoS2, i.e., hydrogen carrier gas, precursors/promotors, and screw dislocations etc.18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26 Recently Rajan et al.22 have proposed a generalized mechanistic model to quantitatively explain the shape evolution of MoS2 monolayers observed experimentally. In spite of these successes, our knowledge on the microscopic process during the growth including nucleation and growth kinetics seems to be still limited, partly due to the few practical difficulties, i.e., the challenge in transferring ultra-fine clusters formed at an early stage of growth and possible loss of intermediate/by-products (some of them are aqueous soluble). As such, comprehensive studies to reveal the microscopic growth mechanism of 2D MoS2 are needed.

In this work, we carried out transmission electron microscopy (TEM) study to capture the nucleation and growth kinetics of 2D MoS2. Here few-layer and mono-layer MoS2 were grown directly on graphene-supported TEM grids,27,28,29,30 and then loaded into the microscope chamber for further microscopic characterizations. No solution was involved in the film transfer process, thus allowing us to visualize the seeding centers, shape morphology, edge structures, and the associated morphology evolved during the growth. We firstly confirmed there exists two forms of seeding centers: (1) Mo-oxysulfide (MoO x S2−y , y ≥ x) nanoparticles either in nested multi-shelled fullerene-like structures or compact nanocrystals, for few-layer MoS2; and (2) atomic scale MoS2 monolayer cluster. For the growth of mono-layer MoS2, the irregular polygon-shaped morphology comprised the following configurations: S-Mo Klein edges and Mo zigzag edges. As the growth proceeded, nearly-triangular shapes were found predominantly, terminated with Mo zigzag edges. Microscopic nucleation mechanism and the growth kinetics can be deduced based on our experimental finding, which were further supported by density-function theory (DFT) calculations.

Results and discussion

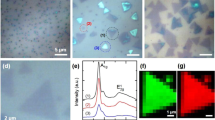

Figure 1a shows the schematic of our CVD system in which (home-made) graphene-supported TEM grids were placed facing-down towards a MoO2-containing boat. Figure 1b, c show two low-magnification annular dark field–scanning transmission electron microscopy (ADF-STEM) images of the as-grown MoS2 samples on graphene under two typical growth conditions where the argon (Ar) flow rates (carrier gas) are different: 200 sccm (Fig. 1b) and 500 sccm (Fig. 1c), respectively. In the former case (i.e., the low argon flow rate region), we observed two primary forms of products (Fig. 1b): few-layer regions bound with thicker/heavier nanoparticles (arrowed) or nanorods (marked with dotted circles in green) and monolayer MoS2 with a nearly-triangular shape (see dotted triangles in red). In contrast, in the latter case (the high argon flow rate region), as-grown samples contained predominating monolayer MoS2, as shown in Fig. 1c.

a Schematic illustration of our CVD system in which graphene-supported TEM grids were placed face down to the MoO2-containing boat. b A typical low-magnification ADF-STEM image representing as-grown products on graphene supports at 200 sccm Ar. The green dotted circles indicate few-layer MoS2 bound with thick/heavy nanoparticle and nanorods (arrowed), while the red dotted circles show monolayer MoS2. c A typical low-magnification ADF-STEM images representing as-grown products at 500 sccm Ar, where monolayer MoS2 predominates (in red dotted circles)

Further ADF-STEM imaging and X-ray energy dispersive spectroscopy (XEDS) analysis were carried out to probe the atomic structure and the chemical compositions of those nanoparticles-like or nanorods-like cores on few-layer MoS2 as shown in Fig. 2 and Fig. S1a, b. Two primary forms were observed: multi-shell fullerene structure (Fig. 2a) or multi-shelled tube (Fig. 2b), with either empty or partially (even completely) filled cores, similar to that of MoS2 inorganic fullerenes;18, 19 compact nanocrystals (Fig. 2c) with few-layer samples. Chemical analysis via STEM-XEDS mapping confirm that it was mostly composed of molybdenum (Mo), sulfur, and oxygen in the shells, while a higher concentration of oxygen was found in the compact core. As such, we can conclude that those nanoparticles or nanorods bound with few-layer flakes are MoS2 multi-shelled fullerenes (nanotubes)19 filled with Mo-oxysulfide (MoO x S2−y , y ≥ x) nanoparticles. During the preparation of this manuscript, we became aware of another work reporting similar fullerene as the seeding materials monolayer MoS x Se(2–x).31 Importantly, we additionally observe another form of nanoparticles, which further XEDS analysis has proved to be MoO x S2−y nanocrystals similar to those cores filled in the multi-shelled fullerene/tubular structure in Fig. 2a. More microscopic studies were carried out to understand the link between these particles and the few-layer MoS2 as shown in Fig. 3 and Fig. S1c in Supplementary Information. Fast fourier-transform (FFT) show the single crystalline nature of most of few-layer MoS2 with different crystallography orientations (see Fig. S1d). The MoS2 fullerene is filled with two MoO x S2−y nanocrystals. No obvious linking was found in crystallography orientation relationship between MoO x S2−y nanoparticles, MoS2 fullerene, and planar few-layer MoS2. The MoO x S2−y compact nanoparticle (red dotted circle) and the few layer MoS2 appear to share a certain crystal orientation relationship with (\(1\bar 10\)) MoOxS2−y // (\(1\bar 10\)) MoS2, and there are identical spacing in {\(1\bar 10\)} planes of few-layer MoS2 (yellow dotted circle) that of the MoOxS2-y compact nanoparticles, as shown in Fig. 3d and the corresponding FFT patterns. Based on these results, a microscopic process from MoO2 to MoS2 during the CVD growth may be speculated as follows: MoO2 belongs to tetragonal crystal system with the {\(1\bar 10\)} spacing of 0.34 nm. During the sulfurization, the intermediate products prefer to retain their tetragonal structure while undergoing a reduction of (\(1\bar 10\)) spacing from 0.34 nm (MoO2) to 0.27 nm (MoO x S2−y , MoS2). As the sulfurization proceeds, the MoO x S2−y was further transformed into hexagonal few-layer MoS2.

a ADF-STEM image of typical nanoparticles with the core-shell fullerene structure. b The corresponding bright field–scanning transmission electron microscopy (BF-STEM) image of typical nanoparticles with the core-shell fullerene structure. c BF-STEM image of structure of empty area of the core. d BF-STEM image of nanoparticles without the core-shell fullerene structure and the corresponding FFT patterns collected from selected regions on few-layer MoS2 (yellow dotted circle) and MoO x S2−y nanoparticle (red dotted circle). e Schematic represents the formation of MoS2 from MoO2 in a CVD process(blue sites are Mo atoms, red sites are S atoms, yellow sites are O atoms)

Given the results shown above, we could assign these nanoparticles (either fullerene/tubular like structure or compact MoO x S2−y nanocrystals) as the centers for the nucleation and feeding source for the growth of MoS2. Under this condition, the sublimated molecular clusters of MoO2 exit mostly in large sizes, and thus may not be completely sulfurized due to the limited reaction time before their deposition onto the graphene substrate. As such, MoO x S2−y nanoparticles are formed on the substrate, and serve as the heterogeneous nucleation sites for the growth of MoS2 in few-layer forms. Such nuclei should also facilitate the nucleation and growth of few-layer MoS2, rather than the monolayer form, either from a few-layer nuclei or through a layer-on-layer growth process. As reaction proceeds, the nanoparticles have two different routes, as the nucleation sites: (1) The chemical conversion occurs much faster than the diffusion of the sulfur gas into the MoO x S2−y nanoparticles, which will be further sulfurized to form the nested multiple-fullerene nanostructures as shown earlier.32 As the sulfurization proceeds, eventually these as-deposited MoO x S2−y nanoparticles may also serve as the feeding source for the growing MoS2. The fully or partially empty cores observed on those multiple fullerenes may be formed as a result of self-sacrifice as the seeding source. Other mechanisms such as Kirkendall effect33 during the sulfurization may also lead to the observed empty-core structures. In some cases, the outer shells in high qualities may block the mass transport and thus the sulfurization, leading the central core having a higher concentration of oxygen, as shown in Fig. 1b. (2) When the c-axis of these as-deposited MoO x S2−y nanoparticles is perpendicular to the graphene plane, the particles will serve as the center of epitaxial growth, so the multiple-fullerene nanostructures will not form.

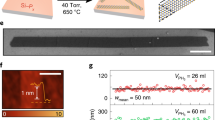

We now turn our attention to detail the case of monolayer MoS2 growth. Figure 4a–l presents the ADF-STEM images of the graphene-supported as-grown monolayer MoS2 with different sizes and morphology. Note here the MoS2 monolayers were grown on different regions of the graphene support under the same CVD condition, and then grouped in size. The varying size and morphology of these MoS2 monolayers on different regions of the same graphene substrate may result from the local fluctuations responsible for nucleation and growth. Of more than 100 samples we checked, it is clearly seen that there are no thick/heavy nanoparticles bound with the MoS2 monolayers, a situation distinctly different with that in few-layer MoS2. On the other hand due, to the unavoidable oxygen-containing PMMA residue (frequently found in Fig. 4a–l) on graphene membranes used during the graphene transferring; therefore it becomes impossible for us to identify residual oxygen within the lattice of MoS2, if any, particularly at the atomic level.

a–i ADF-STEM images of monolayer MoS2 with different sizes found on graphene, illuminating the shape evolution during CVD growth. A number of terraces with atomic steps can be found on the edge (arrowed, not all arrowed). j Low-mag ADF-STEM image of a triangle-shaped MoS2 monolayer, k atomic structure of the region highlighted in yellow dotted circle, l atomic structure of the local region highlighted in red dotted circle

We studied the evolution of shape morphology and edge structure of MoS2 monolayers, another key issue for the growth mechanism study. We treated size-dependent monolayer images, as seen in Fig. 4, as an approximated reflection of the structure evolution that would be followed by the same MoS2 monolayer at the different growth stages. The smallest one found in our experiments has a diameter of close to 3.0 nm (Fig. 4a), and an irregular polygon shape. As the size increases, MoS2 atomic clusters evolves into irregular hexagon shape (Fig. 4f–h); and then into near-triangle shape with truncated corners (Fig. 4i), before they finally form well-known triangular shape, which are decorated mainly with Mo-terminated zigzag edges14,15,16, 34 (written as Mo-zz edge hereafter, see Fig. 4k). Terraces and kinks (arrowed) can be frequently found along the edge of all MoS2 monolayers, serving as chemically active sites for the epitaxy addition of Mo–S molecules or atomic clusters from the supply, either by direct deposition in gas phase or in solids phase after a surface diffusion process. From the results shown above, we can infer that the morphology of MoS2 monolayers changes from irregular polygonal shape to triangular one with an increasing size (Fig. 4a–j).

Accompanying the evolution of structure and mophology during the growth, the edge structure and termination also changed as shown in Fig. 5. Here three MoS2 monolayer samples with different characteristic morphology (irregular polygon, near-hexagon and near-triangle) were chosen as an example for ease of display (Fig. 5a–c) and associated structural models (Fig. 5d–f). Over two primary types of edge structure were found: Mo-zz edge (highlighted with blue lines) and a bare Mo atom bound with zigzag terminated sulfur atoms, similar to the so-called Klein edge in graphite35, written as S–Mo (marked by red lines in Fig. 5a–c) with the corresponding structural models shown as inset in Fig. 5a (blue sites are Mo atoms and red sites are S atoms). For the smallest MoS2 cluster (Fig. 5a, 4b), these two types of edge structure are found approximately in equal number of quantities, and then the Mo-zz edge increases relative to the size of MoS2 and finally becomes predominant. Such an evolution can be more clealy read out from the quantitative analysis (Fig. 5g). In order to explain these experimentally observed edge structures and their evolution, we further performed DFT simulations to calculate the formation energies of four zigzag edge structures (S–Mo, Mo–zz, S–zz (S-terminated zigzag edges) and Mo–S (Mo-terminated zigzag edges attached with two bare S atoms)) as a function of the chemical potential difference-Δμ Mo, Δμ Mo = μ Mo − μ Mo(bulk)), where μ Mo and μ Mo(bulk) represent the chemical potential of Mo atoms in the source precursor and in MoS2 monolayer, respectively. Please refer to the computation details section in Supplementary Information for details of modeling used in this study. The calculated results are shown in Fig. 5h, from which one can read: (i) Mo-terminated edges (S–Mo and Mo–zz) have lower formation energies than those of S-terminated edges (S–S and Mo–S) under the Mo-rich condition (taken to be Δμ Mo > −0.3 eV); (ii) the formation energies of Mo-zz and S-Mo are quite close (i.e., differ only 0.01 eV at Δμ Mo = 0.1 eV).

a ADF-STEM image of irregular shaped monolayer MoS2 cluster with two primary types of edge structure: Mo-zz edge and S-Mo edge (denoted by blue and red lines separately) with the corresponding structural models (blue sites are Mo atoms and red sites are S atoms). b ADF-STEM image of hexagonal-shaped MoS2 c ADF-STEM image of triangle MoS2. d The edge structural model of the irregular MoS2, e the edge structural model of the near-hexagon MoS2. f the edge structural model of the near-triangle MoS2. g Histogram of the amount of the edge atoms with different size. h Results from DFT calculations for the formation energies of different edges as a function of Δμ Mo

The case of microscopic MoS2 monolayers seems to be different from that of the few-layer case. Since no residual MoO x S2−y nanostructures were observed on as-prepared MoS2 monolayers as shown in Fig. 1c and Fig. 4, we can infer that the sublimated MoO2 precursor should mostly form molecular clusters ((MoO2)n, (MoO3)n etc.),36 and sulfurized completely before its deposition on graphene substrate either as nucleation centers, or addition onto already formed nucleation center either directly from vapor ambient or via surface diffusion on graphene substrate. Relative ratios of these clusters can change as the carrier gas flow changes; the presence of MoO x S2−y reduces the sulfur concentration in the reaction zone. As such, it can also well explain the difference in the as-formed products where few-layer MoS2 or monolayer MoS2 dominates, as shown in Fig. 1b, c. According to the DFT calculations, S–Mo and Mo-zz edges are dominant and with comparable ratio at the initial stage during the growth, as shown in Fig. 4. Comparing to the Mo-zz edge, the S–Mo edge should possess relatively higher chemical reactivity due to the bare Mo atoms that will facilitate the incorporation of sourcing clusters, thus leading to a faster growth rate. According to the classic crystal growth theory,37 fast growing edges/facets gradually disappear, while slow-growing edges/facets remain. In this case, it will eventually lead to the formation of triangle-shaped MoS2 monolayer decorated with Mo-zz edges, as most frequently observed. The slightly truncated shape observed on MoS2 mono-layers shown in Fig. 4j, k may be formed due to insufficient growth time, which again provides clear evidence for the proposed kinetics in edge structures, as discussed previously.

Figure 6a–c presents a summarized schematic diagram showing the microscopic process during the growth of few-layer MoS2 under low gas flow (200 sccm) and Fig. 6d–f is the schematic of route for the nucleation and growth kinetics of MoS2 monolayers. We note that Li et al.38 proposed a three-step reaction pathway via examining the distribution of intermediate products in different forms.

From the results and discussions mentioned above, we could put forward some perspectives that may help us get high-quality MoS2. (1) A steady stream-containing partial pressure of Mo and sulfur-containing vapor can help one get a large area MoS2, and is essential towards the precisely controlled growth of MoS2 atomic layers with desired edge structures and shape morphology. (2) For the precisely controlled layer thickness, extra care should be taken to control the sublimation of Mo precursor, and restrain the formation of larger MoO x S2−y nanoparticles on the substrate for growth. (3) Given these considerations, the widely used strategy of the sulfurization of Mo–O precursor in a CVD furnace seems to be too simplistic to fulfill this requirement. Further improvements, including the use of metal-organic CVD39, 40 or molecular beam epitaxy,41 may be a better option. In summary, we directly probe the nucleation seeds, evolution of edge structures and shape of evolution of pristinely-prepared MoS2 materials. Two different types of nucleation centers were resolved: Mo-oxysulfide (MoO x S2−y ) nanoparticles on few-layer samples, and pure molybdenum sulfide clusters for monolayer samples. Nevertheless, it was proposed for a growing MoS2 monolayer that it originates from an irregular polygonal-shaped cluster decorated with S–Mo and Mo–zz edges in a comparable ratio under the Mo-rich condition; then triangle-like shapes with dominant Mo-zz edges are formed as its size increases. A deep understanding of the growth mechanisms of atomically thin MoS2 material via CVD, and other related two-dimensional TMD materials, will pave the way for specific function and property-oriented growth under precise control.

Methods

Graphene films used here were grown on polycrystalline copper foils, and then transferred onto molybdenum-based TEM grids via a PMMA-assisted wet chemistry process.8 Graphene-supported TEM grids were mounted onto a home-built ceramic carrier and loaded into a CVD system, facing down above a boat containing 1 mg of MoO2 precursors (Sigma-Aldrich, 99%). Here we choose MoO2, rather than MoO3 as the precursor for two considerations because of the single-step chemical reaction MoO2 + 3 S → MoS2 + SO2: (1) to reduce the reaction complexity, as a multi-step reduction reaction occurs for the sulfurization of MoO3, (2) to grow high quality MoS2 monolayer.13 The whole CVD setup is shown in Fig. 1a. Within a typical CVD process, the furnace was firstly heated to 300 °C for 10 min and held for additional 10 min, and then heated to 750 °C in 40 min and kept for next 25 min. At about 15 min after the furnace temperature reached 750 °C, heating of 300 mg of sulfur source (Aladdin, 99.999%) was started, with its temperature reaching 180 °C in 2 min, and then held for the next 10 min. During the whole process, argon (99.999%) was used as the carrier gas, with an optimized flow rate of 200 standard-state cubic centimeter per minute (sccm) for growing few-layer samples and of 500 sccm for monolayer samples. The total growth time lasts for about 10 min, and the furnace cooled down naturally. ADF-STEM was conducted with a FEI Chemi-STEM Titan G2 80–200, which was equipped with a probe-side spherical aberration-corrector and operated at an acceleration voltage of 200 kV. The convergent angle for illumination was set to 24 mrads with a probe current of 50–70 pA, and the collection angle was 50–100 mrads. XEDS was carried out on a Bruker super-X detection system.

References

Wilson, J. & Yoffe, A. The transition metal dichalcogenides discussion and interpretation of the observed optical, electrical and structural properties. Adv. Phys. 18, 193–335 (1969).

Kuc, A., Zibouche, N. & Heine, T. Influence of quantum confinement on the electronic sructure of the transition metal sulfide TS2. Phys. Rev. B 83, 245213 (2011).

Balendhran, S. et al. Two-dimensional molybdenum trioxide and dichalcogenides. Adv. Funct. Mater. 23, 3952–3970 (2013).

Sundaram, R. et al. Electroluminescence in single layer MoS2. Nano Lett. 13, 1416–1421 (2013).

Nørskov, J. K., Bligaard, T., Rossmeisl, J. & Christensen, C. H. Towards the computational design of solid catalysts. Nat. Chem. 1, 37–46 (2009).

Todorova, T., Prins, R. & Weber, T. A density functional theory study of the hydrogenolysis and elimination reactions of C2H5SH on the catalytically active (100) edge of 2H-MoS2. J. Catal. 246, 109–117 (2007).

Xie, J. et al. Defect-rich MoS2 ultrathin nanosheets with additional active edge sites for enhanced electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Adv. Mater. 25, 5807–5813 (2013).

Kalantar-zadeh, K. et al. Two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides in biosystems. Adv. Funct. Mater 25, 5086–5099 (2015).

Li, Z. et al. Active light control of the MoS2 monolayer exciton binding energy. ACS Nano 9, 10158–10164 (2015).

Kang, Y. et al. Plasmonic hot electron enhanced MoS 2 photocatalysis in hydrogen evolution. Nanoscale 7, 4482–4488 (2015).

Li, X. et al. Large-area synthesis of high-quality and uniform graphene films on copper foils. Science 324, 1312–1314 (2009).

Reina, A. et al. Few-layer graphene films on arbitrary substrates by chemical vapor deposition. Nano Lett. 9, 30–35 (2008).

Song, L. et al. Large scale growth and characterization of atomic hexagonal boron nitride layers. Nano Lett. 10, 3209–3215 (2010).

Lee, Y. H. et al. Synthesis of large-area MoS2 atomic layers with chemical vapor deposition. Adv. Mater. 24, 2320–2325 (2012).

Zhan, Y., Liu, Z., Najmaei, S., Ajayan, P. M. & Lou, J. Large-area vapor-phase growth and characterization of MoS2 atomic layers on a SiO2 substrate. Small 8, 966–971 (2012).

Bilgin, I. et al. Chemical vapor deposition synthesized atomically thin molybdenum disulfide with optoelectronic-grade crystalline quality. ACS Nano 9, 8822–8832 (2015).

Lin, Y. C. et al. Wafer-scale MoS 2 thin layers prepared by MoO3 sulfurization. Nanoscale 4, 6637–6641 (2012).

Sadan, M. B., Houben, L., Enyashin, A. N., Seifert, G. R. & Tenne, R. Atom by atom: HRTEM insights into inorganic nanotubes and fullerene-like structures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 105, 15643–15648 (2008).

Tenne, R. & Seifert, G. Recent progress in the study of inorganic nanotubes and fullerene-like structures. Annu. Rev. Mater. Sci. 39, 387–413 (2009).

Wang, S. et al. Shape evolution of monolayer MoS2 crystals grown by chemical vapor deposition. Chem. Mater. 26, 6371–6379 (2014).

Chen, L. et al. Step-edge-guided nucleation and growth of aligned WSe2 on sapphire via a layer-over-layer growth mode. ACS Nano 9, 8368–8375 (2015).

Govind Rajan, A., Warner, J. H., Blankschtein, D. & Strano, M. S. Model for the chemical vapor deposition of 2D transition metal dichalcogenide monolayers. ACS Nano 10, 4330–4344 (2016).

Ji, Q., Zhang, Y., Zhang, Y. & Liu, Z. Chemical vapour deposition of Group-VIB metal dichalcogenide monolayers: Engineered substrates from amorphous to single crystalline. Chem. Soc. Rev. 44, 2587–2602 (2015).

Shi, Y., Li, H. & Li, L.-J. Recent advances in controlled synthesis of two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides via vapour deposition techniques. Chem. Soc. Rev. 44, 2744–2756 (2015).

Cao, D., Shen, T., Liang, P., Chen, X. & Shu, H. Role of chemical potential in flake shape and edge properties of monolayer MoS2. J. Phys. Chem. C 119, 4294–4301 (2015).

Chen, L. et al. Screw-dislocation-driven growth of two-dimensional few-layer and pyramid-like WSe2 by sulfur-assisted chemical vapor deposition. ACS Nano 8, 11543–11551 (2014).

Yuk, J. M. et al. High-resolution EM of colloidal nanocrystal growth using graphene liquid cells. Science 336, 61–64 (2012).

Chen, Q. et al. 3D motion of DNA-Au nanoconjugates in graphene liquid cell electron microscopy. Nano Lett. 13, 4556–4561 (2013).

Yuk, J. M., Seo, H. K., Choi, J. W. & Lee, J. Y. Anisotropic lithiation onset in silicon nanoparticle anode revealed by in situ graphene liquid cell electron microscopy. ACS Nano 8, 7478–7485 (2014).

Nair, R. et al. Graphene as a transparent conductive support for studying biological molecules by transmission electron microscopy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 97, 153102 (2010).

Cain, J. D., Shi, F., Wu, J. & Dravid, V. P. On the growth mechanism of transition metal dichalcogenide monolayers: The role of self-seeding fullerene nuclei. ACS Nano 10, 5440–5445 (2016).

Kong, D. et al. Synthesis of MoS2 and MoSe2 films with vertically aligned layers. Nano Lett. 13, 1341–1347 (2013).

Wang, W., Dahl, M. & Yin, Y. Hollow nanocrystals through the nanoscale Kirkendall effect. Chem. Mater. 25, 1179–1189 (2012).

Zhou, W. et al. Intrinsic structural defects in monolayer molybdenum disulfide. Nano Lett. 13, 2615–2622 (2013).

Klein, D. J. Graphitic polymer strips with edge states. Chem. Phys. Lett. 217, 261–265 (1994).

Burns, R., DeMaria, G., Drowart, J. & Grimley, R. J. Mass spectrometric investigation of the sublimation of molybdenum dioxide. Chem. Phys. 32, 1363–1366 (1960).

Dhanaraj, G., Byrappa, K., Prasad, V.& Dudley, M. Springer Handbook of Crystal Growth (Harbin Institute of Technology Press, 2013).

Li, B. et al. Solid–vapor reaction growth of transition-metal dichalcogenide monolayers. Angew. Chem. 128, 10814–10819 (2016).

Van Der Zande, A. M. et al. Grains and grain boundaries in highly crystalline monolayer molybdenum disulphide. Nat. Mater 12, 554–561 (2013).

Kang, K. et al. High-mobility three-atom-thick semiconducting films with wafer-scale homogeneity. Nature 520, 656–660 (2015).

Diaz, H. C., Ma, Y., Chaghi, R. & Batzill, M. High density of (pseudo) periodic twin-grain boundaries in molecular beam epitaxy-grown van der Waals heterostructure: MoTe2/MoS2. App. Phys. Lett. 108, 191606 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Feng Ding for his critical comments, Zhepeng Zhang and Prof. Yanfeng Zhang for providing us highquality graphene samples and the Center of Electron Microscopy of Zhejiang University for the access to the microscope facilities. J.Y. acknowledges supports from Pao Yu-Kong International Foundation for a Chair Professorship in ZJU. H.B.S. acknowledged computational resources from the Shanghai Supercomputer Center. This work was financially supported by the National Basic Research Program of China (Grant No. 2014CB932500 and No. 2015CB921004), the National Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 51472215, No. 51222202, and No. 11404309) and the 111 project (No. B16402). J.Y. acknowledges the EPSRC (UK) funding EP/G070326.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.J. conceived the project; D.Z. carried out most of the experiments (CVD, Raman and TEM), and analyzed the data with the assistance of F.J. V.A. and D.L., under the supervision of C.J.; H.S. carried out the DFT calculations; O.O. J. Y. and Z.Z. contributed to the discussions; D.Z. and C.J. wrote the paper together with the inputs and suggestions from others.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, D., Shu, H., Jiang, F. et al. Capture the growth kinetics of CVD growth of two-dimensional MoS2 . npj 2D Mater Appl 1, 8 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41699-017-0010-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41699-017-0010-x

This article is cited by

-

Excitons in mesoscopically reconstructed moiré heterostructures

Nature Nanotechnology (2023)

-

Composition and phase engineering of metal chalcogenides and phosphorous chalcogenides

Nature Materials (2023)

-

Large area MoS2 thin film growth by direct sulfurization

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Broadband photodetection using one-step CVD-fabricated MoS2/MoO2 microflower/microfiber heterostructures

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Single-crystalline nanoribbon network field effect transistors from arbitrary two-dimensional materials

npj 2D Materials and Applications (2022)