Abstract

Efficient mRNA splicing is a prerequisite for protein biosynthesis and the eukaryotic splicing machinery is evolutionarily conserved among species of various phyla. At its catalytic core resides the activated splicing complex Bact consisting of the three small nuclear ribonucleoprotein complexes (snRNPs) U2, U5 and U6 and the so-called NineTeen complex (NTC) which is important for spliceosomal activation. CWC15 is an integral part of the NTC in humans and it is associated with the NTC in other species. Here we show the ubiquitous expression and developmental importance of the Arabidopsis ortholog of yeast CWC15. CWC15 associates with core components of the Arabidopsis NTC and its loss leads to inefficient splicing. Consistent with the central role of CWC15 in RNA splicing, cwc15 mutants are embryo lethal and additionally display strong defects in the female haploid phase. Interestingly, the haploid male gametophyte or pollen in Arabidopsis, on the other hand, can cope without functional CWC15, suggesting that developing pollen might be more tolerant to CWC15-mediated defects in splicing than either embryo or female gametophyte.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Angiosperms are the predominant group of land plants. A hallmark of this dominance in the course of evolution is the establishment of a reduced haploid phase (called gametophyte) in the life cycle of flowering plants. In free-living gametophytes of mosses, the gametophytic generation forms independently recognizable plants that can even be the dominant structure. In contrast, the gametophyte of flowering plants is reduced to a small dependent structure with an almost minimal number of cells and a short lifetime1. In Arabidopsis, the female gametophyte is deeply embedded in sporophytic tissue, whereas the male gametophyte or pollen has to be released from the sporophytic anther tissue for pollination to occur. Upon successful pollen-stigma interaction, the pollen tube grows inside the transmitting tract towards the ovule. Recent research has revealed that several signaling molecules including peptides play a role in the guidance of the pollen tube, attraction by the female gametophyte and burst of the pollen tube tip within one of the two synergid cells. If any of the aforementioned processes is disrupted, fertilization does not take place. Several mutants with disruptions in these processes have been isolated in the past1,2,3. Upon successful fertilization, the Arabidopsis zygote initiates a precise developmental program, which results in a heart-shaped embryo already comprising all major seedling organs: two primary leaves or cotyledons, a shoot meristem, a hypocotyl, and a primary root with a root meristem4. This invariant embryo patterning and development is impaired in mutants defective for various cellular response pathways e.g. responses to phytohormones, small RNA pathways, vesicular trafficking, cytoskeletal structure, and cell cycle control5,6,7,8,9. Furthermore, mutations in genes that are components of the RNA splicing machinery (spliceosome) affect gametophyte function and embryogenesis. For example, mutations such as gfa1/clotho, rtf2, sus2/prp8, or bud13 cause severely reduced transmission of the mutant alleles via the female gametophyte and cause embryo lethality in Arabidopsis10,11,12,13,14.

The pivotal step of splicing—intron removal—constitutes two trans-esterification reactions, mediated by the spliceosome, a dynamic protein complex containing more than 100 proteins and 5 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particles (snRNP)15, which is likely highly conserved among eukaryotes. The snRNPs consecutively interact with the pre-mRNA. First, U1 snRNP and U2 snRNP interact with the splice and the branch site, respectively. Then U4/U6-U5 snRNPs and the PRP19-CDCL5 complex (so-called NineTeen complex [NTC] in yeast) associate, thereby forming the pre-catalytic spliceosome16. After the dissociation of U4 snRNP, the Prp19 complex stabilizes the interaction of U5 snRNP and U6 snRNP with the spliceosome17,18. Recent studies using cryo-EM uncovered detailed spliceosomal structures during various steps of mRNA splicing. The NTC/PRP19 complex is highly conserved between yeast and human and contains six and seven core proteins, respectively19,20,21,22. Important for the function of the active spliceosome are also the so-called NTC-related (NTR) proteins, of which CWC15 is a member.

The developmental importance of Cwc15 was shown in yeast as a loss of function of Cwc15 confers lethality in Schizosaccharomyces pombe and it is synthetically lethal with prp19-1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae23. Furthermore, in S. cerevisiae it was shown that the core spliceosome components are not equally important for all pre-mRNAs, perhaps explaining why in Arabidopsis the absence of several components might affect tissues differently24. Regarding multicellular eukaryotes, CWC15 was suggested to be important for bovine embryo development25. In Arabidopsis thaliana, CWC15 was not found in a proteomic approach as a member of the NTC26. Many genes coding for components of the core splicing machinery are duplicated in Arabidopsis although mutations in single-copy genes frequently result in gametophytic cell death11,26. Interestingly, the phenotypic consequences of mutations in spliceosomal genes are different between female and male gametophytes. Mutations in CLOTHO, which is a homolog of the yeast U5-associated Snu114, and ATROPOS, whose homolog has a demonstrated role in U2 assembly27, result in defective female gametophytes, whereas male transmission is less severely affected11.

In this work, we address the importance of the predicted splicing factor CWC15 in the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Our results show that CWC15 is associated with homologs of core yeast and human spliceosome components. Furthermore, CWC15 is essential for plant development including embryo development as splicing is affected on a whole-genome level. CWC15 also plays some role in the female gametophyte, however, pollen development proceeds normally in the absence of CWC15.

Results

CWC15 encodes a highly conserved splicing factor with ubiquitous expression

CWC15 was initially described as a spliceosome-associated protein in yeast and human cells. Subsequent cryoEM studies placed it within the core machinery of the spliceosome15,28. Our thorough phylogenetic analysis revealed the evolutionary conservation of CWC15 across all eukaryotes (Supplementary Fig. 1). CWC15 protein appears to have diverged between plants and animals, with specific amino acid sequences distinguishing the clades (Supplementary Fig. 1A and B). Nevertheless, major domains especially in the N- and C-terminal parts of the protein homologs appear to be conserved, which suggests the general importance of CWC15 during splicing in all eukaryotes.

To assess CWC15 expression, we expressed a translational fusion of 3xGFP to a genomic rescue construct. The GFP signal was exclusively nuclear which is consistent with the potential role of CWC15 as a splicing factor. The fusion protein CWC15-3xGFP was ubiquitously expressed in all gametophyte, embryo, and seedling tissues and here too localized to the nucleus (Fig. 1). The integuments and all cells of the mature, unfertilized embryo sac showed GFP fluorescence, including central cell, synergids, and the egg cell (Fig. 1A). Likewise, the male gametophyte was marked by nuclear fluorescence during all developmental stages from unicellular microspore to tricellular, mature pollen (Fig. 1B, Supplementary Fig. 2A–C). Also, all cells of the embryo at the early globular (Supplementary Fig. 2D–F), globular and triangular (Fig. 1C, Supplementary Fig. 2G), late-heart or torpedo and bent-cotyledon stages (Supplementary Fig. 2H–J) showed clear nuclear fluorescent signals. We were also able to detect nuclear fluorescent signals in all cells of seedling tissues such as the cotyledon epidermis with stomata and pavement cells (Fig. 1D, Supplementary Fig. 2K), the primary root with all radially organized cell layers (Fig. 1E), the hypocotyl and the first rosette leaves including trichomes (Fig. 1F, Supplementary Fig. 2L). In summary, CWC15 encodes a ubiquitously expressed, nuclear-localized protein.

Expression pattern of genomic construct gCWC15-3xGFP during plant development. CWC15 expression pattern monitored with a genomic fusion to GFP is visible in all nuclei of gametophytes, embryo, and seedling. (A) Mature female gametophyte with nuclear GFP signal in all tissue types including central cell (asterisk), synergid (arrowhead), and egg cell (arrow). (B) Both vegetative and generative nuclei show CWC15-3xGFP signals in mature pollen grain. Inset: DAPI-stained nuclei in the mature pollen grain. (C) CWC15-3xGFP is present in all nuclei at globular embryo stage. (D) gCWC15-3xGFP expression in epidermal cells. The image is a maximum projection of z-stacks across abaxial cotyledon epidermal cells. Nuclear-localized CWC15-3xGFP is shown in green, cell outlines are stained with propidium iodide (magenta). (E) gCWC15-3xGFP expression in seedling root. Nuclear-localized CWC15-3xGFP is shown in green, cell outlines are stained with Renaissance SR2200 dye (grey). Transverse root section is shown as inset. (F) gCWC15-3xGFP expression in seedling shoot. Nuclear-localized CWC15-3xGFP in primary leaves of a 7-day-old seedling is shown in green, autofluorescence is shown in red. Scale bar: (A–D) 5 μm, (E,F) 100 μm.

CWC15 is closely associated with the Arabidopsis NTC

In yeast and human, CWC15 is an integral part of the core spliceosome20,21. To assess whether CWC15 is a component of the spliceosome in Arabidopsis, we performed immunoprecipitation experiments with GFP-tagged CWC15 and analyzed the precipitates by LC–MS/MS. As controls, we used GFP-tagged IMPORTIN-ALPHA 6 (IMPα6) and transcription factor AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR 5 (ARF5) and carried out immunoprecipitation followed by liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC–MS). Both IMPα6 and ARF5 are also localized to the nucleus, but functionally distinct from CWC1529,30. We looked for peptides that were specifically enriched in the CWC15 but absent in the two other immuno-precipitates. The most abundant peptides recovered were Arabidopsis counterparts of the human Prp19 complex (NTC), U5 snRNP, and NTC-related proteins (NTR) (Table 1). The majority of these mapped to Arabidopsis homologs of human spliceosomal proteins of the NTC such as Cdc5 and Prp19, two proteins that were well described in their function for NTC-related spliceosomal activation31. In addition to CWC15 itself (Ad-002 in human spliceosome), we found a homolog for the human NTC-related (NTR) protein Aquarius, which like CWC15 is required for embryo viability in Arabidopsis (EMB2765)32. Adding peptides with lower counts to our analysis, we detected a majority of all components of the U5 snRNP, NTC, NTR, and associated splicing factors (Supplementary Table 2) that were recently described in a multitude of structural cryo-EM reports for yeast and human spliceosomes15,28. These results suggest that CWC15 is potentially part of the NineTeen complex, which has an important general role in splicing in Arabidopsis thaliana26,33.

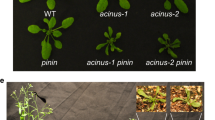

Down-regulation of CWC15 causes developmental defects

In an enhancer trap screen, we identified a T-DNA insertional mutant that displayed several phenotypic features reminiscent of auxin-related defects. Compared to wild type, mutant seedlings and adult plants were strongly reduced in size (Fig. 2A–C). Adult plants were fertile despite stunted growth when compared to Col-0 wild-type plants (Fig. 2C). Mutant seedlings displayed stunted primary roots (Fig. 2B,D) and cotyledon defects ranging from monocots or asymmetrically positioned cotyledons to seedlings with three cotyledons (Fig. 2D). Phenotypic defects were visible in all offspring seedlings from homozygous mother plants when grown on agar plates while heterozygous plants did not show any obvious defects.

Mis-regulation of CWC15 is causative for embryo and seedling phenotypes. (A,B) Normal wild-type (A) and cwc15-1 mutant seedling (B) with short primary root and three cotyledons. (C) Adult cwc15-1 mutant plants (marked by asterisks) grow smaller compared to wild type. (D) Range of cwc15-1 mutant seedling phenotypes with wild-type seedling on the left. Asterisk marks tricot seedling with normal root, arrows point to seedlings with asymmetrically positioned cotyledons, and arrowhead marks seedling with only one fully developed cotyledon. (E) The insertion site of the transgene is in the vicinity of 4 gene loci, among them CWC15 (At3g13200). Mutant alleles with corresponding insertion sites are depicted as cwc15-1 (promoter) and cwc15-2 (SALK insertion line, 3rd intron). Exons are shown as green arrows. Image of gene loci was exported from CLC Genomics Workbench software version 10.1.1 (https://digitalinsights.qiagen.com/products-overview/discovery-insights-portfolio/analysis-and-visualization/qiagen-clc-genomics-workbench/). (F) cwc15-1 rescue lines (at least 6 independent transgenic lines tested for each construct) with seedling phenotypes from left to right: (1) Wild type, (2) cwc15-1 mutant, (3) genomic rescue, (4) rescue with constitutive expression from ribosomal RPS5A promoter, (5) no rescue if expressed from putative promoter of gene At3g10100 which is only active during early embryogenesis. Scale bar: 2 mm.

To determine the genomic insertion site of the transgene that caused the mutant phenotype, we sequenced the entire genome and aligned DNA sequencing reads both to the T-DNA used and the Arabidopsis genome as was previously described34. The insertion was located on the upper arm of chromosome 3 directly upstream of the genomic locus CWC15/AT3G13200 (Fig. 2E). We tested the possible effects of the insertion on the expression of genes near the insertion site through semi-quantitative (sq) RT-PCR (Supplementary Fig. 3). We found that CWC15/AT3G13200 was downregulated and confirmed the strong down-regulation also by quantitative (q) RT-PCR (Supplementary Fig. 4A). Among the other genes flanking the insertion site, we observed additional bands for AT3G13190 and an up-regulation of AT3G13210. AT3G13205 is a predicted pseudogene. Both CWC15/AT3G13200 and AT3G13210 code for putative splicing factors and the additional transcripts observed for AT3G13190 suggested possible splicing defects in the mutant. Since multiple homozygous T-DNA insertion lines located in exons are available for AT3G13210 and therefore its absence is not deleterious for development, we focused on CWC15/AT3G13200, the homolog of the yeast/human splicing factor Cwc15/AD-002. We termed the mutant therefore cwc15-1. A genomic construct expressing the CWC15 gene from about 1 kb of the upstream sequence was able to fully complement the mutant seedling phenotypes (Fig. 2F). The same was observed when a strong ribosomal promoter RPS5A drove expression of CWC15. Interestingly, expression from a promoter only active during early embryogenesis35 did not rescue the observed seedling defects, suggesting that continued protein activity during later embryo and seedling development might be necessary (Fig. 2F).

To elucidate the earliest deviation in development, we analyzed embryos from 2-cell to mid-globular stages comparing wild type to the cwc15-1 mutant. In general, mutant embryos showed a variety of strongly pleiotropic embryo defects when compared to wild type. In Col-0 embryos, the division plane of the apical daughter cell of the zygote is vertical (Fig. 3A). In contrast, mutant embryos often showed a horizontal division plane (Fig. 3B). Also, we observed frequent erroneous divisions in the basal cell lineage of the embryo (Fig. 3C). These phenotypes are for example reminiscent of embryo phenotypes observed in yda or wrky2 mutants36,37. When the wild-type embryos were at the 16-cell stage (Fig. 3D), mutant embryos displayed altered division planes, to varying degrees exhibiting raspberry-like phenotypes38 (Fig. 3E,F). At mid-globular stage (Fig. 3G)—a time point when an asymmetric division of the so-called hypophysis establishes the root—apical and basal domains appeared strongly misshapen, resembling fass mutant phenotypes39 (Fig. 3H,I). In conclusion, mutant embryos displayed a range of phenotypic alterations, which are similar to already described embryo mutants and this suggested that there is potentially mis-regulation of multiple genes during early embryogenesis in the cwc15-1 mutant.

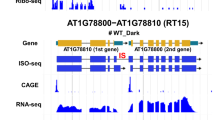

CWC15 is important for efficient splicing

To determine the extent of potential splicing defects in cwc15 mutants, we performed RNA sequencing on total RNA extracted from tissues representing the early and late stages of development. First, we analyzed RNA from wild-type and hypomorphic cwc15-1 seedlings, where we observed a clear phenotypic difference. Second, we did RNA-seq profiling on total RNA extracted from mature pollen tissue from wild-type and cwc15-1 mutants. To assess the comparability of biological replicates we used principal component analysis. Tissue/developmental difference was the major component of variation (accounting for ~ 81%) in expression levels (Supplementary Figure 5A).

To analyze whether specific splice sites across the genome are affected in cwc15-1 mutants, we utilized SpliSER40, which enables the quantification of splicing at the level of individual splice sites. We first compared the variation in splice-site strength of the splice-sites across both tissues through PCA analysis. The PCA analysis revealed that the within tissue/replicate variation is much lower in pollen compared to seedlings, which suggested that our ability to detect differential splicing would be higher in pollen compared to seedlings (Supplementary Figure 5B–D).

The analysis of differential splicing through diffSpliSE in SpliSER (Supplementary Dataset File 1) showed 620 splice sites to be differentially utilized in seedlings, corresponding to 564 genes. Most of the splice sites were canonical, consistent with the notion that CWC15 is an integral component of the core splicing machinery. We saw no clear bias in the prevalence of 5′ or 3′ splice site, 58%, and 42% respectively. SpliSER uses competition between splice sites as a parameter in assessing splice-site strength. The majority of differentially spliced sites (75%) had no competing splice sites observed in any sample, which indicates that they are constitutive splice sites undergoing intron retention (Supplementary Figure 4B). In pollen, we detected 3,997 splice sites to be differentially spliced, across 2,380 genes. 88 of these genes were common to both seedlings and pollen (Fig. 4A). Unlike in seedlings, where a vast majority of differentially-spliced sites showed a decrease in splice-site strength (99.7%), we saw an even distribution of up- and down-regulated splice sites in pollen, with no apparent bias towards a particular splicing event. Together these results suggest that the splicing defect observed in cwc15-1 mutant seedlings is primarily a reduced capacity for the splicing of some introns (i.e. intron retention), rather than a change in splice-site preference (i.e. alternative usage of 3′ and 5′ splice sites, exon skipping, etc.).

Down-regulation of CWC15 in cwc15-1 leads to global splicing defects and transcriptional differences. (A) Venn diagram showing number of genes differentially spliced in seedling and pollen tissue, between wild type and mutant. (B) Venn diagram comparing genes detected as differentially spliced and differentially expressed in pollen. (C) Venn diagram comparing genes detected as differentially spliced and differentially expressed in seedlings. Venn Diagram Plotter v1.5.5228 (https://omics.pnl.gov/software/venn-diagram-plotter) was used to generate Venn diagrams.

Since differences in splicing can indeed lead to changes in expression levels41,42, we compared transcripts that were differentially up- or down-regulated (Supplementary Dataset File 1). 324 genes were differentially expressed more than twofold in seedlings, and 3,864 in pollen. We saw a significant overlap between differentially spliced and differentially expressed genes in pollen (Fig. 4B), but not in seedlings (Fig. 4C), suggesting that the cwc15-1 splicing defects observed in seedlings may not be directly correlated with changes in gene expression. However, given that these results are derived from two RNA-seq replicates, we cannot rule out the tissue-specific differences observed in splicing and gene expression are due to differences in statistical power. To corroborate these results, we performed gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis for differentially spliced and expressed genes in pollen and seedlings (Supplementary Dataset File 2). For differentially spliced genes in both seedlings and pollen we found enrichment for a wide range of processes including numerous GO terms involving metabolism and response to various stimuli with functions in both protein and nucleotide binding. This was also the case for differentially expressed genes in pollen. The number of enriched GO terms for differentially expressed genes in seedlings was considerably lower and we saw enrichment of response terms, the top three hits being related to iron homeostasis which do not appear in any of the other lists.

Taken together, these findings reveal three aspects of CWC15 function. First, even a hypomorphic allele of CWC15 leads to changes in splicing patterns. Second, compromising CWC15 function has a direct and/or indirect effect on gene expression. Third, the effect of CWC15 differs between tissue types and/or stages of development.

Loss of CWC15 function is female gametophytic and embryo lethal

The pleiotropic phenotypes in cwc15-1 are caused by the downregulation of CWC15 transcript levels, indicating that cwc15-1 might be a hypomorphic allele. Therefore, we analyzed a T-DNA insertion allele, with the T-DNA residing in the third intron, termed cwc15-2. For this allele, we never recovered homozygous mutant progeny from heterozygous plants (cwc15-2+/+ n = 114, 48.3% vs. cwc15-2+/− n = 122, 51.7%). When we opened siliques of selfed cwc15-2+/− plants we found missing and shriveled ovules compared to WT, corresponding to aborted ovules (Supplementary Fig. 6). Reciprocal crosses of heterozygous cwc15-2+/− and wild-type plants showed that transmission of the mutant allele via the female gametophyte was reduced from the expected 50% to 29% whereas the male gametophyte seemed not affected at all (Supplementary Table 3).

Next, we analyzed cell type-specific fluorescent marker lines for the female gametophyte expressed in the central cell, the synergid cells, or the egg cell. However, we could not detect any differences in cwc15-2+/− compared to wild type in any of the marker crosses analyzed (n > 100), which suggested that cell identity was not affected in these lines (Supplementary Fig. 6, Supplementary Videos 1–3). This also suggests that the altered function of the female gametophyte rather than aborted development causes the observed decreased female transmission of cwc15-2+/−. To detect defects during pollen tube attraction and fertilization, we used a pollen multiple marker line. Sperm cell nuclei were labeled with a male gamete-specific Histone H3.3-YFP fusion protein (HTR10-YFP) and a centromeric CenH3-mCherry fusion protein (HTR12-mCherry). Upon fertilization, the HTR10-YFP protein is turned over while zygote and endosperm show mCherry fluorescence at the centromeric chromatin, resulting in distinct foci in the zygote and endosperm nuclei43. CWC15 loss of function resulted in a range of phenotypic consequences in pollen tube perception and fertilization (Fig. 5). After successful double fertilization, endosperm nuclei in wild-type plants showed 15 spots of nuclear-localized mCherry signal and no YFP signal could be detected (Fig. 5A). In ovules of cwc15-2+/− plants, however, we frequently observed pollen tubes without double fertilization as indicated by the absence of mCherry signal and the presence of nuclear YFP signal of unfused, persisting sperm cells (Fig. 5B). Also, we observed pollen tube overgrowth inside the ovule (Fig. 5B and C) as well as polytubey (Fig. 5D). Taken together, these observations suggest that CWC15 is required for efficient pollen tube reception and gamete interaction leading to successful double fertilization.

Loss of CWC15 function in cwc15-2 leads to defects in double fertilization. (A–D) Overlay images of wild-type control (A) or CWC15 deficient ovules (B–D) 20 h after pollination expressing pollen double marker visualizing histones of fertilized endosperm nuclei in red (A,C,D), sperm nuclei in green (B,C,D), and SR2200 counter-staining of pollen tube cell walls in white (A–D). Arrowheads mark endosperm nuclei (red), arrows point to sperm nuclei (green), and asterisks indicate pollen tubes (white). Scale bar: 20 µm.

The ratio of aborted ovules from crosses of cwc15-2+/− gynoecia pollinated with pollen from Col-0 anthers (13.6%, n = 132) indicated, as well as the aforementioned reciprocal crosses, that a low percentage of ovules in cwc15-2+/− plants and their egg cells within can be fertilized. To investigate at which stage cwc15-2−/− zygote/embryo development might be arrested, we looked at ovules in cwc15-2+/− plants in self-pollinated flowers 72 h after pollination. We were able to identify seemingly aborted or delayed embryos at zygote and the earliest embryo stages of development (Fig. 6A-D). These results show that CWC15 function is important for female gametophyte development and fertilization and essential for embryogenesis, whereas the male gametophyte is not affected.

Discussion

Although the eukaryotic spliceosome machinery is evolutionarily conserved, there are species-specific differences. The spliceosome and the activating NineTeen complex show differences in both the number and nature of proteins involved between yeast, human and Arabidopsis26,44,45. In Arabidopsis, for example, there seems to be a duplication and likely redundancy of factors playing major roles during splicing (e.g., Prp8 or Prp19)33. One of the single-copy genes previously associated with the splicing machinery is CWC15. Our thorough phylogenetic analysis indicated that CWC15 is present and conserved in virtually all eukaryotic genomes. Until recently, knowledge about the exact function of CWC15 has been scarce. Protein–protein interaction data revealed CWC15 as a protein associated with yeast and human spliceosomes23,46. CWC15 was later considered an integral part of the Prp19 complex/NTC through its direct interaction with CDC547,48. In Arabidopsis, however, co-precipitation with Prp19 could not be demonstrated and CWC15 was therefore deemed not being part of the NTC26,49. In contrast, our mass spectrometry-based analysis showed co-precipitation of most Arabidopsis NTC components with CWC15, indicating that there is a close interaction of CWC15 with the NTC in Arabidopsis. We also detected other components of the core spliceosomal machinery, which is in line with recent structural data gained from yeast and human spliceosomes. The yeast homolog Cwf15/Cwc15 interacts with several U5 snRNA components and together with Prp45 is thought to be important for the stability of the spliceosomal core or main body20,45,50,51,52. Like the yeast multi-protein complex, the human CWC15 counterpart Ad-002 is also present at the core region of the human spliceosome21,44,53 and might be modified by human spliceosome-specific peptidyl-prolyl isomerases for functional catalytic activity54. Structures of plant spliceosomes have yet to be determined, but Arabidopsis CWC15 possibly has a similarly central role in the spliceosomal multi-protein complex as do the homologous proteins in yeast and human.

Alternative splicing (AS) is very common in humans, where essentially 100% of the transcripts have at least two isoforms55. The prevalent form of AS in animals is exon skipping56. We have utilized an approach that allows the detection of specific splice-sites that show aberrant usage between samples40. It has been estimated that 61% of Arabidopsis genes undergo AS, with the majority of AS events being intron retention57 which in turn leads to nonsense-mediated decay (NMD) of the affected transcript56. However, in plants retained introns do not always trigger NMD58. In Arabidopsis, AS can be achieved by cell type-specific expression patterns of splicing factors59,60 and this has been studied mainly during flowering time61. In our work, RNA sequencing analysis in a hypomorphic mutant background with seedling and adult growth defects showed that a decrease in CWC15 protein abundance causes clear splicing defects. While differences in splicing can lead to expression differences, in cwc15 mutants, the observed differences in gene expression cannot be solely attributed to splicing defects. Additional changes in expression may be secondary effects resulting from splicing abnormalities. The phenotypic severity increased strongly in a putative knock-out mutant of CWC15 which showed pleiotropic fertilization defects and was embryo lethal. It has been previously shown that mutations in splicing factors primarily affect the viability of the female gametophyte11,12,62,63. Likewise, loss of the splicing factor CWC15 caused strongly decreased transmission via the female gametophyte while the pollen was entirely unaffected. Several studies detected new transcripts, differential splicing and even alternative transcriptional start sites in pollen when compared to leaf tissues64,65. However, transcripts enriched in pollen appear to have roles in splicing which could contribute to increased robustness of the pollen when compared to the egg cell. It has been shown that so-called housekeeping genes can be linked to specific mutant phenotypes as is the case for various splicing factors that affect the development of the female gametophyte66. This could explain why the loss of CWC15, and other splicing factors causes different phenotypes between male and female gametophytes. Curiously, recent research showed that a pair of splicing factors specifically affects the male gametophyte in double mutants but not the female gametophyte67. Future research will show if the composition of the splicing machinery in plants is indeed tissue-specific and is possibly involved in the different needs of various tissue types during development.

Material and methods

Plant material and in silico analysis

The wild-type plant line used was the Col-0 accession and plants were grown as previously described35. The T-DNA insertion line cwc15-2+/− (SALK_010555, Col-0) was provided by the Nottingham Arabidopsis Stock Centre (NASC). The transgenic marker lines for specific cell types in the female gametophyte pEC1:HTA6-3xeGFP, pNTA > > ntdTomato, and pMEA:3xGFP as well as the multi-color marker were previously described43,68.

Acquisition of protein sequences, sequence alignment, and generation of the phylogenetic tree was performed as shown before69. Representation of protein sequence alignment in RasMol color and sequence conservation was done with CLC Genomics Workbench software version 10.1.1.

Molecular cloning

The sequences of primers used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table 4. Both the CWC15 genomic rescue construct and the translational GFP fusion construct were generated by PCR amplifying a 2,825 bp fragment including 1,087 bp upstream of the CWC15 start codon and cloned into GIIK-tNOS (CWC15 genomic start and stop primers) and GIIK-3xeGFP-tNOS (CWC15 genomic start and -TAG stop primers), respectively, using restriction enzymes SalI/BclI. GIIK-pRPS5A:CWC15-tNOS was cloned by PCR amplifying the 693 bp CWC15 coding sequence (CDS) with CWC15 CDS start and stop primers and inserting the CDS into GIIK-pRPS5A-tNOS70 using restriction site BclI. The construct for early embryo expression was cloned by amplifying a 2 kb promoter element upstream of the AT3G10100 start codon35 with AT3G10100 start and stop primers and inserting the amplicon into GIIK-tNOS, using restriction enzymes XhoI/SmaI. The CWC15 CDS was subsequently amplified with CWC15 CDS start and stop primers, and restriction enzyme BclI was used for cloning into GIIK-pAT3G10100-tNOS.

Whole-genome sequencing

Genomic DNA was extracted from pooled cwc15-1 seedlings 6 days after germination (6 dag), using the Qiagen DNeasy Plant Mini Kit. Libraries for DNA Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) were prepared with 1 µg DNA, using the Illumina TruSeq DNA PCR-free Low Throughput Library Prep Kit and Single Indexes Set A, and sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 2000 machine. The transgenic insertion site in cwc15-1 was initially determined by aligning sequencing reads to the Arabidopsis genome (https://www.araport.org/data/araport11) and the border region of the transgenic construct, using CLC Genomics Workbench software version 10.1.1. The insertion site was confirmed by PCR genotyping of border regions, using transgenic and genomic primers (LB and cwc15-1 genotyping start primers, 341 bp; RB and cwc15-1 genotyping stop primers, 323 bp), and subsequently by Sanger sequencing of PCR products.

PCR genotyping

The cwc15-2 T-DNA allele was genotyped with primers cwc15-2 RP, cwc15-2 LP, and T-DNA-specific primer LBa1 (wild-type allele RP + LP 824 bp, T-DNA containing allele RP + LBa1 approximately 450 bp). The cwc15-2− insertion site was determined by sequencing the T-DNA allele PCR product, using primer LBb1.3.

sqRT-PCR and qRT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from Col-0 and cwc15-1 mature pollen or pooled seedlings 6 dag, using the Qiagen RNeasy Plant Mini Kit and on-column DNase digest (Qiagen RNase-free DNase Set). Reverse transcription was carried out with 1 µg total RNA using the RevertAid RT Reverse Transcription Kit (Thermo Scientific). For sqRT-PCR analysis, the following PCR conditions were used: 94° for 5 min followed by 30 or 35 cycles of 94° for 10 s, 58° for 30 s, and 72° for 1 min with a final extension step 72° for 5 min. For qRT-PCR analysis, we used the intronless and ubiquitously expressed control gene UBQ10 for normalization and the following PCR program: 95° for 3 min followed by 40 cycles of 95° for 10 s, 60° for 10 s, and 72° for 20 s. Gene AT3G08950 as an example for splice-site usage was randomly chosen from among the top sites from Supplementary Dataset 1. Example gene AT2G34060 was among the not statistically significant sites. All primers used can be found in Supplementary Table 4.

RNA sequencing, splicing, and GO enrichment analysis

Gene lists for differential expression and splicing analysis as well as GO terms can be found in the Supplementary Dataset Files 1 and 2. As described above, total RNA was extracted from two biological replicates for both pollen and seedlings and libraries for RNA NGS were prepared with 1 µg total RNA, using Illumina TruSeq RNA Library Prep Kit v2 and sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 2000 machine. RNA-seq data were mapped using STAR v2.5.271, taking only uniquely mapping reads, with minimum intron size 20, and maximum intron size 6,000. A splice junction BED file was generated using RegTools v0.5.272 with the same intron limits. Each mapped RNA-seq sample was processed with SpliSER v0.1.1 and analyzed using the diffSpliSE pipeline40. To maintain the accuracy of the quantification, a splice site would be filtered out unless each replicate being assessed had at least 10 reads showing evidence of its utilization, or non-utilization. When comparing RNA from wild-type and cwc15-1 seedlings, SpliSER detected 247,741 splice sites with sufficient read coverage in all samples; in pollen 66,191 splice sites were detected with sufficient read coverage in all samples.

For differential gene expression analysis, read counts were extracted from RNA-seq alignments using featureCounts v1.5.173. Differential gene expression was called using DESeq2 v1.22.274 with read counts normalized using the sizeFactors() function. Genes with a corrected p-value < 0.05 and log2FoldChange > ± 2 were taken as differentially expressed. Differential gene expression PCA plots used DESeq2 regularized-log transformation read counts (rlog() function). Overlaps between gene lists were tested through hypergeometric probabilities. Venn diagrams were generated with Venn Diagram Plotter Software v1.5.5228 (https://omics.pnl.gov/software/venn-diagram-plotter). For gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis, we took lists of genes that showed differential expression or that contained differentially spliced sites. Gene lists were uploaded to the AgriGO web portal (v2.0)75, and we performed singular enrichment analysis using the TAIR10_2017 background gene set. A corrected p-value less than 0.05 was considered to be significant.

Microscopy

Images of seedlings and plants were taken with a Canon EOS 1000D camera. Clearing of ovules or embryos and staining with SR2200 were done as previously described35,43. Images of embryos were taken with a Zeiss Axio Imager. Fluorescent proteins were imaged using Leica TCS SP8, Olympus FV1000, or Zeiss LSM780 NLO confocal laser scanning microscopes and LAS X, FLUOVIEW, or ZEN software respectively. Images were processed using ImageJ version 1.52i and Adobe Photoshop and Illustrator CS6.

Immunoprecipitation and LC–MS/MS analysis

Precipitation of GFP-tagged proteins from seedlings 6 dag and subsequent mass spectrometry analysis was in essence the exact same procedure as was described previously76,77. Briefly, 1–2 g fresh weight seedling material was ground in liquid nitrogen, using mortar and pestle. The resultant seedling powder was suspended in 2–3 ml lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 2 mM EDTA, 0.5% Triton X-100) containing 20–30 µl Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (P9599, Sigma-Aldrich). After centrifugation, the supernatant was filtered with Miracloth (Calbiochem) and 2 ml of the supernatant was incubated with 20 µl GFP-Trap beads (Chromotek) for 3 h at 4 °C, using a tube rotator. The magnetic beads were washed three times with wash buffer (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 0.1% Triton X-100) on a magnetic stand. Bead-bound proteins were eluted by boiling in 1 × Laemmli buffer and purified by SDS-PAGE followed by in-gel Trypsin digest. The digested peptides were subjected to LC–MS/MS analysis and MS spectra were processed with MaxQuant package software version 1.5.2.8 with integrated Andromeda search engine78.

References

Dresselhaus, T., Sprunck, S. & Wessel, G. M. Fertilization mechanisms in flowering plants. Curr. Biol.26, R125–R139 (2016).

Huck, N., Moore, J. M., Federer, M. & Grossniklaus, U. The Arabidopsis mutant feronia disrupts the female gametophytic control of pollen tube receptor. Development130, 2149–2159 (2003).

Takeuchi, H. & Higashiyama, T. Tip-localized receptors control pollen tube growth and LURE sensing in Arabidopsis. Nature531, 245–248 (2016).

Lau, S., Slane, D., Herud, O., Kong, J. & Jürgens, G. Early embryogenesis in flowering plants: setting up the basic body pattern. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol.63, 483–506 (2012).

Lukowitz, W., Mayer, U. & Jürgens, G. Cytokinesis in the Arabidopsis embryo involves the syntaxin-related KNOLLE gene product. Cell84, 61–71 (1996).

Hamann, T., Mayer, U. & Jürgens, G. The auxin-insensitive bodenlos mutation affects primary root formation and apical-basal patterning in the Arabidopsis embryo. Development126, 1387–1395 (1999).

Hemerly, A. S., Ferreira, P. C. G., Van Montagu, M., Engler, G. & Inzé, D. Cell division events are essential for embryo patterning and morphogenesis: Studies on dominant-negative cdc2aAt mutants of Arabidopsis. Plant J.1, 123–130 (2000).

Steinborn, K. et al. The Arabidopsis PILZ group genes encode tubulin-folding cofactor orthologs required for cell division but not cell growth. Genes Dev.16, 959–971 (2002).

Nodine, M. D. & Bartel, D. P. MicroRNAs prevent precocious gene expression and enable pattern formation during plant embryogenesis. Genes Dev.24, 2678–2692 (2010).

Schwartz, B. W., Yeung, E. C. & Meinke, D. W. Disruption of morphogenesis and transformation of the suspensor in abnormal suspensor mutants of Arabidopsis. Development120, 3235–3245 (1994).

Moll, C. et al.CLO/GFA1 and ATO are novel regulators of gametic cell fate in plants. Plant J.56, 913–921 (2008).

Liu, M. et al.GAMETOPHYTIC FACTOR 1, Involved in Pre-mRNA Splicing, Is Essential for Megagametogenesis and Embryogenesis in Arabidopsis. J. Integr. Plant Biol.51, 261–271 (2009).

Sasaki, T. et al. An Rtf2 Domain-containing protein influences pre-mRNA splicing and is essential for embryonic development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genetics200, 523–535 (2015).

Xiong, F. et al.AtBUD13 affects pre-mRNA splicing and is essential for embryo development in Arabidopsis. Plant J.98, 714–726 (2019).

Shi, Y. Mechanistic insights into precursor messenger RNA splicing by the spliceosome. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol.18, 655–670 (2017).

Will, C. L. & Lührmann, R. Spliceosome structure and function. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol.3, a003707 (2011).

Chan, S. P. & Cheng, S. C. The Prp19-associated complex is required for specifying interactions of U5 and U6 with pre-mRNA during spliceosome activation. J. Biol. Chem.280, 31190–31199 (2005).

Chan, S. P., Kao, D. I., Tsai, W. Y. & Cheng, S. C. The Prp19p-associated complex in spliceosome activation. Science302, 279–282 (2003).

Yan, C., Wan, R., Bai, R., Huang, G. & Shi, Y. Structure of a yeast activated spliceosome at 3.5 Å resolution. Science353, 904–911 (2016).

Wan, R., Yan, C., Bai, R., Huang, G. & Shi, Y. Structure of a yeast catalytic step I spliceosome at 3.4 Å resolution. Science353, 895–904 (2016).

Zhang, X. et al. An atomic structure of the human spliceosome. Cell169, 918-929.e14 (2017).

Fica, S. M., Oubridge, C., Wilkinson, M. E., Newman, A. J. & Nagai, K. A human postcatalytic spliceosome structure reveals essential roles of metazoan factors for exon ligation. Science363, 710–714 (2019).

Ohi, M. D. & Gould, K. L. Characterization of interactions among the Cef1p-Prp19p-associated splicing complex. RNA8, 798–815 (2002).

Pleiss, J. A., Whitworth, G. B., Bergkessel, M. & Guthrie, C. Transcript specificity in yeast pre-mRNA splicing revealed by mutations in core spliceosomal components. PLoS Biol.5, 745–757 (2007).

Sonstegard, T. S. et al. Identification of a nonsense mutation in CWC15 associated with decreased reproductive efficiency in Jersey cattle. PLoS ONE8, e54872 (2013).

Koncz, C., deJong, F., Villacorta, N., Szakonyi, D. & Koncz, Z. The spliceosome-activating complex: molecular mechanisms underlying the function of a pleiotropic regulator. Front. Plant Sci.3, 9 (2012).

Nesic, D. & Kramer, A. Domains in human splicing factors SF3a60 and SF3a66 required for binding to SF3a120, assembly of the 17S U2 snRNP, and prespliceosome formation. Mol. Cell. Biol.21, 6406–6417 (2001).

Nguyen, T. H. D. et al. CryoEM structures of two spliceosomal complexes: starter and dessert at the spliceosome feast. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol.36, 48–57 (2016).

Schlereth, A. et al. MONOPTEROS controls embryonic root initiation by regulating a mobile transcription factor. Nature464, 913–916 (2010).

Herud, O., Weijers, D., Lau, S. & Jürgens, G. Auxin responsiveness of the MONOPTEROS-BODENLOS module in primary root initiation critically depends on the nuclear import kinetics of the Aux/IAA inhibitor BODENLOS. Plant J.85, 269–277 (2016).

Chanarat, S. & Sträßer, K. Splicing and beyond: the many faces of the Prp19 complex. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res.1833, 2126–2134 (2013).

Jia, T. et al. The Arabidopsis MOS4-associated complex promotes microRNA biogenesis and precursor messenger RNA splicing. Plant Cell29, 2626–2643 (2017).

Meyer, K., Koester, T. & Staiger, D. Pre-mRNA splicing in plants: in vivo functions of RNA-binding proteins implicated in the splicing process. Biomolecules5, 1717–1740 (2015).

Polkoa, J. K. et al. Illumina sequencing technology as a method of identifying T-DNA insertion loci in activation-tagged Arabidopsis thaliana plants. Mol. Plant5, 948–950 (2012).

Slane, D. et al. Cell type-specific transcriptome analysis in the early Arabidopsis thaliana embryo. Development141, 4831–4840 (2014).

Lukowitz, W., Roeder, A., Parmenter, D. & Somerville, C. A MAPKK kinase gene regulates extra-embryonic cell fate in Arabidopsis. Cell116, 109–119 (2004).

Ueda, M., Zhang, Z. & Laux, T. Transcriptional activation of Arabidopsis axis patterning genes WOX8/9 links zygote polarity to embryo development. Dev. Cell20, 264–270 (2011).

Yadegari, R. et al. Cell differentiation and morphogenesis are uncoupled in Arabidopsis raspberry embryos. Plant Cell6, 1713–1729 (1994).

Torres-Ruiz, R. A. & Jürgens, G. Mutations in the FASS gene uncouple pattern formation and morphogenesis in Arabidopsis development. Development120, 2967–2978 (1994).

Dent, C. et al. Splice-site strength estimation: a simple yet powerful approach to analyse RNA splicing https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.02.12.946756 (2020).

Sureshkumar, S., Dent, C., Seleznev, A., Tasset, C. & Balasubramanian, S. Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay modulates FLM-dependent thermosensory flowering response in Arabidopsis. Nat. Plants2, 16055 (2016).

Hartmann, L. et al. Alternative splicing substantially diversifies the transcriptome during early photomorphogenesis and correlates with the energy availability in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell28, 2715–2734 (2016).

Musielak, T. J., Schenkel, L., Kolb, M., Henschen, A. & Bayer, M. A simple and versatile cell wall staining protocol to study plant reproduction. Plant Reprod.28, 161–169 (2015).

Haselbach, D. et al. Structure and conformational dynamics of the human spliceosomal Bact complex. Cell172, 454-464.e11 (2018).

Yan, C., Wan, R., Bai, R., Huang, G. & Shi, Y. Structure of a yeast step II catalytically activated spliceosome. Science355, 149–155 (2017).

Makarova, O. V. et al. A subset of human 35S U5 proteins, including Prp19, function prior to catalytic step 1 of splicing. EMBO J.23, 2381–2391 (2004).

Grote, M. et al. Molecular architecture of the human Prp19/CDC5L complex. Mol. Cell. Biol.30, 2105–2119 (2010).

Van Maldegem, F. et al. CTNNBL1 facilitates the association of CWC15 with CDC5L and is required to maintain the abundance of the Prp19 spliceosomal complex. Nucleic Acids Res.43, 7058–7069 (2015).

Monaghan, J. et al. Two Prp19-like U-box proteins in the MOS4-associated complex play redundant roles in plant innate immunity. PLoS Pathog.5, e1000526 (2009).

Yan, C. et al. Structure of a yeast spliceosome at 3.6-angstrom resolution. Science349, 1182–1191 (2015).

Bai, R., Yan, C., Wan, R., Lei, J. & Shi, Y. Structure of the post-catalytic spliceosome from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Cell171, 1589–1598 (2017).

Galej, W. P. et al. Cryo-EM structure of the spliceosome immediately after branching. Nature537, 197–201 (2016).

Bertram, K. et al. Cryo-EM structure of a human spliceosome activated for step 2 of splicing. Nature542, 318–323 (2017).

Zhang, X. et al. Structure of the human activated spliceosome in three conformational states. Cell Res.28, 307–322 (2018).

Lee, Y. & Rio, D. C. Mechanisms and regulation of alternative pre-mRNA splicing. Annu. Rev. Biochem.84, 291–323 (2015).

Kornblihtt, A. R. et al. Alternative splicing: a pivotal step between eukaryotic transcription and translation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol.14, 153–165 (2013).

Staiger, D. & Simpson, G. G. Enter exitrons. Genome Biol.16, 136 (2015).

Shaul, O. Unique aspects of plant nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. Trends Plant Sci.20, 767–779 (2015).

Fang, Y., Hearn, S. & Spector, D. L. Tissue-specific expression and dynamic organization of SR splicing factors in Arabidopsis. Mol. Biol. Cell15, 2664–2673 (2004).

Li, S., Yamada, M., Han, X., Ohler, U. & Benfey, P. N. High-resolution expression map of the Arabidopsis root reveals alternative splicing and lincRNA regulation. Dev. Cell39, 508–522 (2016).

Park, Y. J., Lee, J. H., Kim, J. Y. & Park, C. M. Alternative RNA splicing expands the developmental plasticity of flowering transition. Front. Plant Sci.10, 1–7 (2019).

Groß-Hardt, R. et al.LACHESIS restricts gametic cell fate in the female gametophyte of Arabidopsis. PLoS Biol.5, e47 (2007).

Ohtani, M., Demura, T. & Sugiyama, M. Arabidopsis root initiation defective1, a DEAH-box RNA helicase involved in pre-mRNA splicing, is essential for plant development. Plant Cell25, 2056–2069 (2013).

Loraine, A. E., McCormick, S., Estrada, A., Patel, K. & Qin, P. RNA-seq of Arabidopsis pollen uncovers novel transcription and alternative splicing. Plant Physiol.162, 1092–1109 (2013).

Estrada, A. D., Freese, N. H., Blakley, I. C. & Loraine, A. E. Analysis of pollen-specific alternative splicing in Arabidopsis thaliana via semi-quantitative PCR. PeerJ3, e919 (2015).

Tsukaya, H. et al. How do ‘housekeeping’ genes control organogenesis? Unexpected new findings on the role of housekeeping genes in cell and organ differentiation. J. Plant Res.126, 3–15 (2013).

Park, H. Y., Lee, H. T., Lee, J. H. & Kim, J. K. Arabidopsis U2AF65 regulates flowering time and the growth of pollen tubes. Front. Plant Sci.10, 569 (2019).

Kong, J., Lau, S. & Jürgens, G. Twin plants from supernumerary egg cells in Arabidopsis. Curr. Biol.25, 225–230 (2015).

Slane, D., Reichardt, I., El Kasmi, F., Bayer, M. & Jürgens, G. Evolutionarily diverse SYP1 Qa-SNAREs jointly sustain pollen tube growth in Arabidopsis. Plant J.92, 375–385 (2017).

Weijers, D., Geldner, N., Offringa, R. & Jürgens, G. Seed development: early paternal gene activity in Arabidopsis. Nature414, 709–710 (2001).

Dobin, A. et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics29, 15–21 (2013).

Feng, Y.-Y. et al. RegTools: integrated analysis of genomic and transcriptomic data for discovery of splicing variants in cancer (2018).

Yang, L., Smyth, G. K. & Wei, S. featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics30, 923–930 (2014).

Anders, S. & Huber, W. DEseq2: differential gene expression analysis based on the negative binomial distribution. Genome Biol.11, R106 (2010).

Tian, T. et al. agriGO v2.0: a GO analysis toolkit for the agricultural community, 2017 update. Nucleic Acids Res.45, 122–129 (2017).

Singh, M. K. et al. A single class of ARF GTPase activated by several pathway-specific ARF-GEFs regulates essential membrane traffic in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genet.14, e1007795 (2018).

Speth, C. et al. Arabidopsis RNA processing factor SERRATE regulates the transcription of intronless genes. Elife7, e37078 (2018).

Cox, J. et al. Andromeda: a peptide search engine integrated into the MaxQuant environment. J Proteome Res.10, 1794–1805 (2011).

Acknowledgements

We thank the Nottingham Arabidopsis Stock Centre for providing T-DNA insertion lines, Martin Vogt for his assistance, and the Genome Center of the Max Plank Institute for Developmental Biology for their support. Research in our lab was supported by the German Science Foundation (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft – DFG: SFB 1101/B01 to MB) and the Max Planck Society. Portions of this research (Venn Diagram Plotter Software) were supported by the W.R. Wiley Environmental Molecular Science Laboratory, a national scientific user facility sponsored by the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Biological and Environmental Research and located at PNNL. PNNL is operated by Battelle Memorial Institute for the U.S. Department of Energy under contract DE-AC05-76RL0 1830. Research on splicing in SB group is supported by Australian Research Council Discovery Project DP190101479. Open access funding provided by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.S., C.H.L., S.L., M.B., and G.J. designed the study. D.S., C.H.L., M.K., C.D., Y.M., M.F.W., and M.B. performed the experiments and evaluated the data. S.B. and B.M. analyzed and interpreted the experimental results. D.S. wrote the manuscript. All authors commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Slane, D., Lee, C.H., Kolb, M. et al. The integral spliceosomal component CWC15 is required for development in Arabidopsis. Sci Rep 10, 13336 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-70324-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-70324-3

This article is cited by

-

The spliceosome-associated protein CWC15 promotes miRNA biogenesis in Arabidopsis

Nature Communications (2024)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.