Abstract

Studies comparing Billroth-I (B-I) with Roux-en-Y (R-Y) anastomosis are still lacking and inconsistent. The aim of this trial was to compare the quality of life (QoL) of B-I with R-Y reconstruction after curative distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer. A total of 140 patients were randomly assigned to the B-I group (N = 70) and R-Y group (N = 70) with the comparable baseline characteristics. The overall postoperative morbidity rates were 18.6% and 25.7% in the B-I group and R-Y group without significant difference. More estimated blood loss and longer surgical duration were found in the R-Y group. At the postoperative 1 year time point, the B-I group had a higher score in pain, but lower score in global health. However, the R-Y anastomosis was associated with lower incidence of reflux symptoms at postoperative 6 months (P = 0.002) and postoperative 9 months (P = 0.007). The multivariable analyses of variance did not show any interactions between the time trend and grouping. For the results of endoscopic examination, the degree and extent of remnant gastritis were milder significantly in the R-Y group. The stronger anti-reflux capability of R-Y anastomosis contributes to the higher QoL by reducing the reflux related gastritis and pain symptoms, and promotes a better global health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gastric cancer remains a disease with high incidence and is responsible for about 10% of all cancer-related deaths in the world1. Although the incidence of gastric cancer at the upper third of stomach has gradually increased over the years, distal gastric cancers as well as distal gastrectomy are still the mainstream2. In recent years, the overall survival of patients with gastric cancer has improved as the increase of proportion of early gastric cancer detection, the implementation of standard D2 lymphadenectomy, the development of chemotherapy and new targeted drugs3,4,5. Accompanied with the improved survival, the quality of life (QoL) has attracted more attentions than before. One of the most associated factors with QoL of patients after gastrectomy is the type of digestive tract reconstruction.

Billroth-I (B-I) and Roux-en-Y (R-Y) reconstruction after distal gastrectomy have been widely applied. Both B-I and R-Y have their own advantages and disadvantages. B-I has merits of technical simplicity and preservation of physiological food passage. However, patients undergoing B-I reconstruction frequently suffer from the reflux symptoms, which could cause remnant gastritis and esophagitis, even increase the possibility of remnant gastric cancer or esophageal cancer6, 7. In the contrast, R-Y reconstruction has strong capacity to prevent bile reflux theoretically8. Nevertheless, patients with R-Y reconstruction often complain so-called stasis syndrome, which has the significant postoperative symptoms including abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting9, 10. Furthermore, the difficulty of postoperative duodenal endoscopic examination makes surgeons reluctant to perform R-Y reconstruction.

Currently, although a few studies have compared the morbidity, mortality and QoL of B-I with R-Y anastomosis, their findings are still inconsistent11,12,13,14,15,16. Moreover, most of the studies which compared B-I with R-Y anastomosis were carried out in Japan and Korea where the proportions of early gastric cancer are more than 50%17. Therefore, the generalizability of such evidence to other countries where most of the patients has advanced gastric cancer still needs addressing. In addition, there was no study to dynamically compare the QoL of B-I with R-Y reconstruction by standard questionnaires at multiple time points.

Therefore, we performed a prospective randomized controlled trial (RCT) to compare B-I with R-Y reconstruction after curative distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer in China. Here, we reported the results of 1-year interim analysis.

Materials and Methods

Patients

The inclusion criteria were the following: patients aged 18 to 75 with tolerance of the operation; the score of World Health Organization performance status being less than 2; preoperative diagnosis of gastric adenocarcinoma was confirmed by gastric endoscopy and biopsy; the tumors located at lower third of stomach for which distal gastrectomy was feasible; the preoperative staging of potential curative resectable tumors was less than T4aN2M0 according to the 3rd English edition of Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma18; either open gastrectomy or laparoscopic assisted gastrectomy was included. The exclusion criteria consisted of: patients with history of previous laparotomy (except appendectomy and laparoscopic cholecystectomy); patients needed receiving total gastrectomy or combined organ resection (except cholecystectomy) for curative purpose; patients were diagnosed with other gastric malignances, such as lymphoma and gastrointestinal stromal tumor etc, any previous malignancies or synchronous malignancies; emergency cases because of perforation or bleeding of tumor; patients had neo-adjuvant chemotherapy or perioperative radiotherapy.

This study was registered on Chinese Clinical Trial Register (ChiCTR), WHO (SN. ChiCTR-TRC-10001434, date of registration: November 24th, 2010), and approved by the West China Hospital research ethics committee, and the study was done in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent were obtained from all patients.

Study design

After being generated by random number table, the random allocation sequence was concealed and sealed in sequential numbered and opaque envelopes, which were uncovered following the initial laparotomy to assess the eligibility of patients. Then, included patients were randomly assigned to the B-I or R-Y group in a 1:1 ratio intraoperatively. In this study, patients, surgeons, staffs who collected data and analyzed outcomes were not blinded. During the study period, the study protocol was not amended.

Surgical technique

The nasogastric tube was placed routinely before the operation. All the patients underwent distal gastrectomy with D2 lymphadenectomy according to the Japanese gastric cancer treatment guideline19. All the anastomoses were completed by using the mechanical staplers and reinforced by interrupted full-thickness sutures. Briefly, the end-to-side gastroduodenostomy was made by 25 mm circular stapler between the duodenal stump and posterior wall of the remnant stomach in the B-I group. And the gastric stump was closed by linear stapler. In the R-Y group, the duodenum was divided and closed by a linear stapler 3 cm distal to the pylorus. Then, the duodenal stump was reinforced by interrupted full-thickness sutures and interrupted seromuscular sutures. For reconstruction, the proximal jejunum was identified and divided 15–20 cm distant from the Treitz ligament firstly. Next, the gastrojejunostomy was performed between posterior wall of the remnant stomach and antimesenteric border of the distal jejunums with a 25 mm circular stapler in a side-to side fashion. Then, a side-to-side jejunojejunostomy was created between the antimesenteric borders of the proximal and distal jejunums 45 cm below the gastrojejunostomy. The gastric stump and two jejunal stumps were closed by linear staplers. The mesenteric defect was closed with interrupted sutures.

In the patients who received laparoscopic surgery, we performed laparoscopic assisted distal gastrectomy. After the lymph nodes dissection by using laparoscopy, a mini-incision at length of 5–8 cm was made above the umbilicus. Then specimen was removed and extracorporeal digestive tract reconstruction was performed through the incision. The procedures and staplers used for specimen removal and anastomosis were as same as the open cases.

The drain was also placed routinely through the Winslow foramen. All the surgeons adhered with the protocol. The adherence and the quality of operation were evaluated by the study group through scanning the intraoperative photos.

Postoperative care protocol

After the operation, a standardized postoperative care protocol was applied. Intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis and parenteral nutritional support were given to all patients. The nasogastric tube was removed after the first gas-passing, and sips of water started thereafter. Liquid diet and soft diet were given over the next 2 days gradually. The drain was usually removed on postoperative day 5 if there were no complications. If there was no complications after 1 day of soft diet, discharge of patients was encouraged. If there were any compilations, treatments were given individually.

Outcome measurements

The primary end point of this RCT was QoL. The data of QoL was collected by the validated European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) core questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30, version 3.0), and stomach module questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-STO22)20. The EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaire contains 30 items, which could be used to assess the QoL of all kinds of cancer patients. The 30 items could be incorporated into five functional scales (physical, role, cognitive, emotional, and social), three symptom scales (pain, fatigue, nausea and vomiting), six single items (dyspnea, insomnia, appetite loss, constipation, diarrhea and financial difficult) and one global health status scale. Except for the global health scale in which the item values range from 1 to 7, other items are scored 1 to 4, corresponding to the four response categories, namely “Not at all”, “A little”, “Quite a bit” and “Very much”21. The EORTC QLQ-STO22 questionnaire comprises 22 items, which could be divided into five symptom scales (dysphagia, pain, eating restrictions, reflux symptoms, and anxiety) and four single items (having a dry mouth, taste, body image, and hair loss)22. A high score represents a high/healthy level of functioning or QoL for a functional scale or the global health status; whereas a high level of symptomatology/problems for symptom scales/items21. The preoperative baseline of QoL was obtained 3 days before the operation. Postoperative QoL, recurrence and survival status were collected every 3 months after the operation by telephone calls, letters or outpatient visits. No patient was lost to follow-up.

The secondary end points were operative safety, postoperative recovery and severity of postoperative gastritis. Clinicopathologic terminology was based on the 3rd English edition of Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma18. Morbidity, spectrum of complications and mortality were compared. The complications were classified according to the Clavien-Dindo Classification23. The estimated blood loss, operative duration, postoperative hospital stay, mean time to the first flatus and mean time to the first food intake were also compared. The severity of postoperative gastritis was evaluated by endoscopic examination at postoperative 12 months and graded according to the “residue, gastritis, bile” classification24.

Statistical analyses

The sample size was calculated by using a two-sided alpha error of 5% under the normal distribution with a standard deviation of 0.1. And the effect size was determined according to Kojima’s study which showed that the heartburn rates of the B-I group and R-Y group were 37% and 8% at the postoperative 1 year respectively15. The planned sample size was calculated as 56 in each arm. Finally, we enrolled 70 patients in each arm, allowing for a 15–20% dropout rate.

SPSS 19.0 software (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analysis. All QLQ-C30 and QLQ-STO22 responses were linearly transformed to scores from 0 to 100 according to EORTC scoring manuals21. Quantitative data was expressed as means ± standard deviation (SD) and tested by One-way ANOVA test. For categorical data, the Chi-square was used to compare frequencies. Non-parametric tests were performed for non-normal distribution data. Multivariable analysis of variance was applied to investigate the interaction of time and grouping. A P value of less than 0.05 (two-sided) was considered statistically significant. An intention-to-treat analysis was applied as the main statistical method to avoid potential biases.

Results

Characteristics of patients

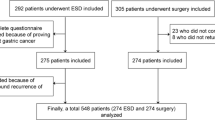

From May, 2011 to May, 2014, a total of 140 gastric cancer patients who underwent distal gastrectomy were randomly assigned to the B-I group (N = 70) and R-Y group (N = 70). In B-I group, there were 6 patients converting to the R-Y anastomosis because of the presence of tension between the duodenum and remnant stomach. In R-Y group, 6 patients underwent the B-I anastomosis due to the willingness or economical consideration of patients’ families. As of postoperative 1 year, 2 patients in the B-I group and 1 patient in the R-Y group recurred, 1 patient in the R-Y group died due to chemotherapy associated hepatic failure. Figure 1 shows the trial profile. The baseline characteristics of patients were comparable between the two groups (Table 1).

Operative variable and Postoperative recovery

There was no perioperative mortality. The overall postoperative morbidity rates were 18.6% (13/70) and 25.7% (18/70) in the B-I group and R-Y group without significant difference (P = 0.309). Postoperative pulmonary infection was the most frequent complication in both groups. There was no anastomosis-related complications. The constitution of complications between the two groups had no significant difference. The estimated blood loss and surgical duration were significantly less in the B-I group. There were no significant differences in terms of postoperative hospital stay, time to first gas-passing, time to first oral intake, time to nasogastric decompression removal and time to drain removal between the two groups. The details can be seen in Table 2.

Assessment of QoL

Except for the insomnia item, there was no significant difference of baseline QoL between the groups (Table 3). With respect to the EORTC QLQ-C30 items, no significant differences were identified between the two groups at the postoperative 3 months and 6 months. For insomnia, a better outcome was observed in the B-I group with difference about 7 points at postoperative 9 months; however, this difference turned to not significant at postoperative 1 year. At the postoperative 1 year time point, a higher score of global health status and a lower score of pain were detected in the R-Y group compared with the B-I group, which showed an overall average difference of 3 points and 6 points respectively. And R-Y group had showed a better trend for the dyspnea item without significant difference. The other scales, such as physical functioning, fatigue, diarrhea, and financial difficulties, were not significantly different between the two groups (Table 3, Fig. 2).

The scores of physical functioning, role functioning and global health status increased; while the scores of pain, nausea and vomiting showed decreased trends from the postoperative 3 months to the postoperative 1 year. However, there were no significant variations of other scales accompanied with the time trend. The multivariable analyses of variance did not show any interactions between the time trend and grouping, which meant that the variation of each scale accompanied with the time trend did not depend on the grouping (Fig. S1, supporting information).

Regarding to the QLQ-STO22 items, R-Y anastomosis was associated with lower incidence of reflux symptoms at postoperative 6 months (P = 0.002) and postoperative 9 months (P = 0.007). However, these differences discontinued to postoperative 1 year. A significant lower score of pain was noted in the R-Y group at postoperative 1 year (P = 0.008). However, there were no significant differences on symptoms such as dysphagia, eating restrictions, having a dry mouth, change of taste, anxiety, body image and hair loss (Table 4, Fig. 2).

The dysphagia, pain, reflux symptoms and eating restrictions became better from the postoperative 3 months to the postoperative 1 year. However, these trends were not observed in other scales. The multivariable analyses of variance also demonstrated no interaction between the time trend and grouping (Fig. S2, supporting information).

Endoscopic findings

No significant differences were found in terms of food residual and bile reflux between the two groups. However, the severity of remnant gastritis was milder significantly in the R-Y group, compared with the B-I group. There was only 32.6% of patients in the B-I group suffering from gastritis less than grade 2. The corresponding percentage in the R-Y group was 58.7% (Table 5).

Discussion

Our results showed that there was no perioperative mortality in either group, and the morbidity and postoperative recovery were comparable between the two groups. However, the estimated blood loss and surgical duration were significantly less in the B-I group, which was accordance with the previous reports. One multicenter RCT in Japan found that there was 34 minutes longer of average operation time in the R-Y group than B-I group, but the overall morbidity were not significantly different (13.6% vs. 8.6%)13. Kitagami et al. also observed the similar results in the cohorts with laparoscopic distal gastrectomy16. The technical-simplicity of B-I anastomosis, which has only one anastomosis and the exemption of duodenal stump handling compared with R-Y group, might attribute to the less blood loss and operation time. However, Ishikawa and Kojima et al. demonstrated that there were no significant differences in terms of operation time and blood loss between the two groups, either in open surgery or laparoscopic surgery11, 15. These discrepancies could be partly explained by the different operative habits of surgeons, procedures of anastomoses (e.g. hand-sewn or stapling) and surgical instruments (e.g. linear or circular stapler). Some previous researches pointed out that there might be a higher possibility of anastomotic leakage in the B-I anastomosis13, 15, 25, which was associated with the impaired blood supply of duodenal stump and excessive tension of anastomotic site15, 25. However, there were no anastomosis related complications in the present study. Two cases of intraperitoneal infections were observed in the R-Y group, which might be caused by a longer exposure of digestive tract since longer operation time and more anastomosis were needed.

The R-Y stasis syndrome, which is characterized by the stasis symptoms of upper gastrointestinal tract after R-Y anastomosis, might be induced by an ectopic pace which arises from the proximal part of the Roux limb after the division of small intestine and separates the normal pace from the duodenum26, 27. Ishikawa et al. found that 20.8% of patients in the R-Y group developed stasis in the early postoperative period11. Otsuka et al. also demonstrated that 11.6% of patients experienced R-Y stasis syndrome28. Therefore, some surgeons advocated to perform the uncut R-Y anastomosis, in order to keep the continuity of digestive tract and decrease the incidence of R-Y stasis syndrome29, 30. Nevertheless, the results remained inconsistent even though the uncut R-Y anastomosis was performed. The reason might be not only the continuity of digestive tract, but also the vagus nerve was divided in the operation for gastric cancer. In our study, however, there was only 1 patient suffering from stasis in each group and no significant differences were found in terms of food residual between the two groups, which was consistent with other reports15.

Quality of life has been regarded as an important outcome measurement parameter and emphasized in cancer patients. If the same oncological outcomes could be achieved, the postoperative QoL would be an influence factor of the selection of surgical procedures. The clinical practicability and validity of EORTC QLQ-C30 and stomach module QLQ-STO22 questionnaires to assess the QoL of patients with gastric cancer have been proven in many studies22, 31,32,33, including the Chinese version of QLQ-C30 and QLQ-STO22 for Chinese patients32, 33.

The present study found that physical functioning, role functioning and global health improved while pain, nausea and vomiting, dysphagia, pain, reflux symptoms and eating restrictions attenuated from the postoperative 3 months to 1 year. Furthermore, these variations accompanied with the time trend did not depend on the grouping. These results suggested that the removal of tumor could improve the QoL and alleviate the digestive symptoms. Moreover, these improvements were independent on the anastomotic methods, which was supported by the findings of Katagami’s study16. At the same time, our study showed that the change of QoL could continue to the postoperative 1 year even longer. Nakamura et al. also found that symptom scales at 12 months were not significantly different, but were significantly better in the B-I group at 36 months after gastrectomy34. These were different from the previous studies indicating that the postoperative 6 months was a cut-point of QoL35, 36.

Regarding the reflux symptom, many studies have showed that R-Y anastomosis could reduce the reflux symptom and reflux-related gastritis and esophagitis, and improve the QoL accordingly8, 11, 12, 15, 37,38,39. In this study, we also noticed a decreased incidence of reflux symptom in the R-Y group at postoperative 6 months and 9 months. As time went by, however, the differences of QoL between the two groups diminished. Therefore, there were no statistical differences between the two groups at postoperative 1 year although still better in the R-Y group. In fact, the endoscopic examination found no significant difference in terms of reflux between the two groups at postoperative 1 year. Nevertheless, the degree and extent of remnant gastritis were milder in the R-Y group since more severe reflux has already existed in the B-I group for a long time.

Our results showed that the R-Y group had a marginal better control of dyspnea symptom (P = 0.053). The Japanese RCT also found the superior dyspnea symptom scale in the R-Y group14. However, the authors considered that this symptom seemed to be physiologically unrelated to postoperative complications14. Insomnia was also considered more as psychological issues than physiological ones40. This may be one of the reasons why the scores of insomnia item fluctuated.

Pain is a kind of subjective feeling, which is influenced by many factors, such as postoperative intraperitoneal adhesions20, the incidence and severity of reflux symptom and cholelithiasis etc. Mathias et al. demonstrated that the pain symptoms was the secondary to a defect in motor function of Roux limb and could be observed almost in all the patients undergoing R-Y reconstruction9. Takiguchi et al. showed that there was no significant difference in terms of pain scale until postoperative 3 years between the two kinds of anastomoses14. Nunobe et al. also reported that no significant difference on pain was noted between the B-I group and R-Y group at postoperative 5 years37. However, the present study found that R-Y anastomosis could result in milder pain significantly at postoperative 1 year, which might benefit from the alleviated reflux-related remnant gastritis. Decreased reflux and pain could contribute to a better global health status at postoperative 1 year in the R-Y group.

There are some limitations of this study. Firstly, the QoL data was obtained by questionnaires, which was a kind of subjective data and easy to be biased by patients’ feeling, cultural background and educational level. Although inevitable in the studies about QoL, using questionnaires to evaluate the QoL is an internationally accepted research approach. Secondly, our interim analysis only reported the 1 year results of this study. We would continue to follow up the patients and evaluate the long-term QoL. Furthermore, more outcome measurements including anemia, stone of gallbladder and long-term survival would be reported in the future. Finally, although being a popular reconstruction method after distal gastrectomy, the Billroth-II anastomosis was considered to be inferior to its counterparts in terms of the postoperative complications, anti-reflux capability and potential risk of remnant gastric cancer8, 39. Therefore, the Billroth-II anastomosis was not considered in the design of the trial.

In conclusion, both B-I and R-Y anastomosis are safe and feasible which could be applied in the clinical practice. The stronger anti-reflux capability of R-Y anastomosis contributes to a higher QoL by reducing the reflux related gastritis and pain symptoms, and promoting a better global health.

Change history

25 April 2018

A correction to this article has been published and is linked from the HTML and PDF versions of this paper. The error has not been fixed in the paper.

References

Torre, L. A. et al. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin 65, 87–108 (2015).

Colquhoun, A. et al. Global patterns of cardia and non-cardia gastric cancer incidence in 2012. Gut 64, 1881–1888 (2015).

Songun, I., Putter, H., Kranenbarg, E. M., Sasako, M. & van de Velde, C. J. Surgical treatment of gastric cancer: 15-year follow-up results of the randomised nationwide Dutch D1D2 trial. Lancet Oncol 11, 439–449 (2010).

Noh, S. H. et al. CLASSIC trial investigators. Adjuvant capecitabine plus oxaliplatin for gastric cancer after D2 gastrectomy (CLASSIC): 5-year follow-up of an open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 15, 1389–1396 (2014).

Bang, Y. J. et al. ToGA Trial Investigators. Trastuzumab in combination with chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for treatment of HER2-positive advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer (ToGA): a phase 3, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 376, 687–697 (2010).

Richter, J. E. Duodenogastric reflux-induced (alkaline) esophagitis. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol 7, 53–58 (2004).

Fein, M. et al. Duodenoesophageal reflux induces esophageal adenocarcinoma without exogenous carcinogen. J Gastrointest Surg 2, 260–268 (1998).

Fukuhara, K. et al. Reconstructive procedure after distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer that best prevents duodenogastroesophageal reflux. World J Surg 26, 1452–1457 (2002).

Mathias, J. R., Fernandez, A., Sninsky, C. A., Clench, M. H. & Davis, R. H. Nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain after Roux-en-Y anastomosis: motility of the jejuna limb. Gastroenterology 88, 101–107 (1985).

Woodward, A., Sillin, L. F., Wojtowycz, A. R. & Bortoff, A. Gastric stasis of solids after Roux gastrectomy: is the jejunal transection important? J Surg Res 55, 317–322 (1993).

Ishikawa, M. et al. Prospective randomized trial comparing Billroth I and Roux-en-Y procedures after distal gastrectomy for gastric carcinoma. World J Surg 29, 1415–1421 (2005).

Namikawa, T. et al. Roux-en-Y reconstruction is superior to billroth I reconstruction in reducing reflux esophagitis after distal gastrectomy: special relationship with the angle of his. World J Surg 34, 1022–1027 (2010).

Imamura, H. et al. Morbidity and mortality results from a prospective randomized controlled trial comparing Billroth I and Roux-en-Y reconstructive procedures after distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer. World J Surg 36, 632–637 (2012).

Takiguchi, S. et al. Osaka University Clinical Research Group for Gastroenterological Study. A comparison of postoperative quality of life and dysfunction after Billroth I and Roux-en-Y reconstruction following distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer: results from a multi-institutional RCT. Gastric Cancer 15, 198–205 (2012).

Kojima, K., Yamada, H., Inokuchi, M., Kawano, T. & Sugihara, K. A comparison of Roux-en-Y and Billroth-I reconstruction after laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy. Ann Surg 247, 962–967 (2008).

Kitagami, H. et al. Evaluation of the delta-shaped anastomosis in laparoscopic distal gastrectomy: midterm results of a comparison with Roux-en-Y anastomosis. Surg Endosc 28, 2137–2144 (2014).

Yang, K. et al. Strategies to improve treatment outcome in gastric cancer: A retrospective analysis of patients from two high-volume hospitals in Korea and China. Oncotarget 7, 44660–44675 (2016).

Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma: 3rd English edition. Gastric Cancer 14, 101–112 (2011).

Japanese gastric cancer association. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2010 (ver. 3). Gastric Cancer 14, 113–123 (2011).

Liu, J. et al. Quality of life following laparoscopic-assisted distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Hepatogastroenterology 59, 2207–2212 (2012).

Fayers, P. M. et al. On behalf of the EORTC Quality of Life Group. The EORTC QLQ-C30 Scoring Manual (3rd Edition). European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer; Brussels, (2001).

Vickery, C. W. et al. Development of an EORTC disease-specific quality of life module for use in patients with gastric cancer. Eur J Cancer 37, 966–971 (2001). EORTC Quality of Life Group.

Clavien, P. A. et al. The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: five-year experience. Ann Surg 250, 187–196 (2009).

Kubo, M. et al. Endoscopic evaluation of the remnant stomach after gastrectomy: proposal for a new classification. Gastric Cancer 5, 83–89 (2002).

Fujiwara, M. et al. Laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy with systemic lymph node dissection for early gastric carcinoma: a review of 43 cases. J Am Coll Surg 196, 75–81 (2003).

Morrison, P., Miedema, B. W., Kohler, L. & Kelly, K. A. Electrical dysrhythmias in the Roux jejunal limb: cause and treatment. Am J Surg 160, 252–256 (1990).

Miedema, B. W. & Kelly, K. A. The Roux stasis syndrome. Treatment by pacing and prevention by use of an ‘uncut’ Roux limb. Arch Surg 127, 295–300 (1992).

Otsuka, R., Natsume, T., Maruyama, T., Tanaka, H. & Matsuzaki, H. Antecolic reconstruction is a predictor of the occurrence of roux stasis syndrome after distal gastrectomy. J Gastrointest Surg 19, 821–824 (2015).

Park, J. Y. & Kim, Y. J. Uncut Roux-en-Y Reconstruction after Laparoscopic Distal Gastrectomy Can Be a Favorable Method in Terms of Gastritis, Bile Reflux, and Gastric Residue. J Gastric Cancer 14, 229–237 (2014).

Yun, S. C., Choi, H. J., Park, J. Y. & Kim, Y. J. Total laparoscopic uncut Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy after distal gastrectomy. Am Surg 80, E51–E53 (2014).

Aaronson, N. K. et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst 85, 365–376 (1993).

Wan, C. et al. Validation of the simplified Chinese version of EORTC QLQ-C30 from the measurements of five types of inpatients with cancer. Ann Oncol 19, 2053–2060 (2008).

Huang, C. C., Lien, H. H., Sung, Y. C., Liu, H. T. & Chie, W. C. Quality of life of patients with gastric cancer in Taiwan: validation and clinical application of the Taiwan Chinese version of the EORTC QLQ-C30 and EORTC QLQ-STO22. Psychooncology 16, 945–949 (2007).

Nakamura, M. et al. Randomized clinical trial comparing long-term quality of life for Billroth I versus Roux-en-Y reconstruction after distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Br J Surg 103, 337–347 (2016).

Zieren, H. U., Jacobi, C. A., Zieren, J. & Müller, J. M. Quality of life following resection of oesophageal carcinoma. Br J Surg 83, 1772–1775 (1996).

Barbour, A. P. et al. Health-related quality of life among patients with adenocarcinoma of the gastro-oesophageal junction treated by gastrectomy or oesophagectomy. Br J Surg 95, 80–84 (2008).

Nunobe, S. et al. Billroth 1 versus Roux-en-Y reconstructions: a quality-of-life survey at 5 years. Int J Clin Oncol 12, 433–439 (2007).

Zong, L. & Chen, P. Billroth I vs. Billroth II vs. Roux-en-Y following distal gastrectomy: a meta-analysis based on 15 studies. Hepatogastroenterology 58, 1413–1424 (2011).

Lee, M. S. et al. What is the best reconstruction method after distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer? Surg Endosc 26, 1539–1547 (2012).

Tomaszewski, K. A. et al. Main influencing factors and health-related quality of life issues in patients with oesophago-gastric cancer - as measured by EORTC tools. Contemp Oncol (Pozn) 17, 311–316 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This work was internal supported by Volunteer Team of Gastric Cancer Surgery (VOLTGA), West China Hospital, Sichuan University, P.R.China. The authors thank Dr. Li-Fei Sun (Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery, West China Hospital, China), for his kind language modification of the manuscript. Domestic support from (1) National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81301867, 81372344); (2) Sichuan Province Youth Science & Technology Innovative Research Team (No. 2015TD0009); (3) 1. 3. 5 project for disciplines of excellence, West China Hospital, Sichuan University; (4) The Scientific Research Program of Public Health Department of Sichuan Province, China (No. 120196).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study conception and design: Yang, Zhang, Chen, Hu; Acquisition of data: Yang, Zhang, Liu, Chen; Analysis and interpretation of data: Yang, Zhang, Zhou, Hu; Drafting of manuscript: Yang; Critical revision: Yang, Zhang, Hu.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, K., Zhang, WH., Liu, K. et al. Comparison of quality of life between Billroth-І and Roux-en-Y anastomosis after distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer: A randomized controlled trial. Sci Rep 7, 11245 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-09676-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-09676-2

This article is cited by

-

Higher incidence of cholelithiasis with Roux-en-Y reconstruction compared with Billroth-I after laparoscopic distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer: a retrospective cohort study

Langenbeck's Archives of Surgery (2024)

-

Stapler insertion angle toward the esophagus reduces the incidence of early postoperative Roux stasis syndrome after distal gastrectomy in minimally invasive surgery

BMC Surgery (2023)

-

Comparison of the gastric microbiome in Billroth I and Roux-en-Y reconstructions after distal gastrectomy

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Dynamics of glucose levels after Billroth I versus Roux-en-Y reconstruction in patients who undergo distal gastrectomy

Surgery Today (2022)

-

Techniques for reconstruction after distal gastrectomy for cancer: updated network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials

Langenbeck's Archives of Surgery (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.