Abstract

Since 1989, China has established a system of powerful laws and regulations aimed to preserve its rich natural flora and fauna. However, this legislative framework still has shortcomings, in terms of sentencing standards across related crimes and the extent of scientific basis for sentences. Here, we review Chinese biodiversity protection laws and some example cases with the goal of suggesting ways to increase law compliance and thus better protect biodiversity. In particular, our suggestions involve regular updates of threat assessments based on scientific evidence including herbaceous plants, fungi and algae; considering ecological differences among the species groups and ensuing ecological damage and financial profit gained; and a differentiation of punishment between organized and individual crimes, with a preference for custodial sentences for the former and monetary fines for the latter, to comply better with international standards and to minimize the incentive to engage in such conduct.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services highlights a global extinction risk for 1 million species1. IPBES member governments, including China, agreed to counteract and implement suitable policies and laws for the protection of species and ecosystems. With one-tenth of global species2, China’s responsibility is particularly high. However, China’s population grew by 250% between 1950 and 20173,4, with an ensuing exploitation of natural resources that led to the degradation of natural ecosystems5,6 and overall biodiversity. The country now has numerous extinct or increasingly threatened species7,8,9, with large mammals particularly threatened by hunting10,11,12, and wild plants, especially Chinese medicinal herbs and orchids, subject to over-collection13. Consequently, China requires a strong and efficient legislative system. Since 1989, several national nature protection laws and regulations have been set in place (Box 1). Their critical role in wildlife protection is indicated by the recovery of many threatened species, but overall biodiversity is still declining14,15,16.

To further improve biodiversity conservation in China, the implementation of a systematic legal framework has been proposed17,18 in addition to improving public awareness and efficiency of law execution19. Based on long-term experience of environmental law enforcement, we identified five shortcomings in the current legislative framework. We believe that addressing these can improve overall wildlife protection while simultaneously avoiding overly harsh sentences (Fig. 1). In this Perspective, we discuss these shortcomings on the basis of case studies and propose remedial measures to increase effectiveness of biodiversity protection in species-rich countries such as China.

Colours under ‘shortcomings’ and ‘consequences’ match the components of the legal framework. Protected species are listed in the Catalogue of Wildlife under Special State Conservation (CW) and the Catalogue of Wild Plants under Special State Conservation (CWP) as the basis of law enforcement regulated by the Wildlife Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China (WPL) and the Forestry Law of the People’s Republic of China (FL). The catalogues also inform the Judicial Interpretation of Several Questions Concerning the Application of Law in the Trial of Criminal Cases of Destruction of Wildlife Resources (JIW) and the Judicial Interpretation of Several Questions Concerning the Specific Application of Law in the Trial of Criminal Cases of Destruction of Forest Resources (JIF), which stipulate the number of specimens harmed, killed, transported or sold to define the ‘seriousness’ of a crime (Box 1). On this basis, the Criminal Law of the People’s Republic of China (CL) sets the sentencing standards. The Regulations on the Protection and Management of Wild Medicinal Resources (RWR) and the Regulations of the People’s Republic of China on the Protection of Wild Plants (RWP) stipulate measures and legal responsibilities for biodiversity protection but do not have law status. Instead, analogies from the Judicial Interpretation of Several Questions Concerning the Specific Application of Law in the Trial of Criminal Cases of Destruction of Forest Resources are applied. Shortcomings of the different aspects of the legal framework have direct consequences on biodiversity protection, balanced sentencing and appropriateness of deterrence strategies, but also indirect impacts when, for example, imbalanced sentencing leads to inappropriate deterrence strategies which, in turn, can lead to a lack of biodiversity protection. Also, uncertainty in law execution, for example, expressed by frequent revocation of sentences, can lead to inappropriate deterrence on the one hand or lack of protection on the other.

Shortcomings of China’s biodiversity protection framework

Here we present five current shortcomings identified in China’s biodiversity protection framework.

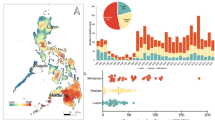

Varying threat-assessment quality and uniform treatment of species

In this section, we highlight how the threat classifications of the Catalogue of Wildlife under Special State Conservation can lead to sentences that are not commensurate with the species’ threat level. In recent amendments to the catalogue, insect species occur in the highest protection classes (3 species out of 234 in Class I and 72 species out of 746 in Class II; Fig. 2) with similar sentencing standards as for large mammals and birds. For instance, killing more than six individuals of Class I protected insects is treated equally to killing one giant panda, with a punishment of at least ten years’ imprisonment according to the Judicial Interpretation of Several Questions Concerning the Application of Law in the Trial of Criminal Cases of Destruction of Wildlife Resources.

In June 2002, 10 poachers captured 263 adults of the butterfly Teinopalpus aureus, meant to be sold on the black market. As T. aureus is listed in Class I of the Catalogue of Wildlife under Special State Conservation, based on the assumption of being rare, the punishment was 5 to 13 years’ imprisonment20. However, recent observations indicate both a wider distribution range21,22 and larger population sizes than initially assumed23. Further, the reproduction rate of insects is generally much higher than that of mammals, which usually makes insects more resistant to the removal of specimens. This case raised some controversy about the scientific basis for classification and the financial profit that can be made with insects compared with mammals24. On the black market, T. aureus can be sold for 700 Chinese yuan per male (~US$100; US$1 = 6.9932 yuan, 21 July 2020; gross domestic product (GDP) per capita: 30,808 yuan in 2010, 54,139 yuan in 2016) and 3,500 yuan per female (~US$500; personal communication with collectors in 2011), while a pair of giant pandas is usually rented to abroad zoos for about 7 million yuan (~US$1 million) per year25.

In 2015, a college student and a farmer took 16 fledglings of the Eurasian hobby (Falco subbuteo), a Class II protected species, and were sentenced to 10.5 and 10 years’ imprisonment and fines of 10,000 and 5,000 yuan, respectively26. However, ecological studies indicate that the distribution range, population density and reproduction rate of F. subbuteo in China seem sufficient for sustaining viable populations27, highlighting the potential of overly harsh punishment when classification lacks scientific basis.

In contrast to valuation according to (black) market prices, wild species also provide higher-level socioeconomic benefits28. For instance, the value of insect pollination services in China was estimated to be 886.5 billion yuan (US$131 billion) in 201529. In comparison, the ecosystem services related to the giant panda were estimated at between 18 billion and 48 billion yuan per year (US$2.6–6.9 billion) in 2010, but they seem more indirect via regulating, provisioning and cultural services provided by the panda reserves30. However, pollination services are provided by multiple species within a highly flexible network31,32 and the impact of removing a particular amount of specimens is hard to assess, whereas large mammals, such as the giant panda, are irreplaceable in ecosystems and their roles as umbrella species. Thus, differences between insects and mammals are striking not only in terms of direct financial profit but also in terms of ecological and socioeconomic damage, and therefore it is questionable that they are both listed in the highest protection class with the same stringent punishment.

Lack of quantitative sentencing standards for herbaceous plants, fungi and algae

Here, we discuss how limited scientific knowledge for particular species groups can lead to legal uncertainties and consequently to limited protection or overly harsh punishment. The Regulations of the People’s Republic of China on the Protection of Wild Plants identify the legal responsibilities for the protection of wild plants (excluding trees), but have not yet reached the status of a law and thus are without judicial interpretation of the Supreme People’s Court and respective sentencing standards. Instead, stipulations of ‘seriousness’ are used with regard to the sentences used for trees, defined in the Judicial Interpretation of Several Questions Concerning the Specific Application of Law in the Trial of Criminal Cases of Destruction of Forest Resources (Box 1), and respective sentencing standards, defined in the Criminal Law of the People’s Republic of China, are applied (up to seven years’ imprisonment). With this analogy, an offender was sentenced to three years in prison in 2016 (suspended sentence) and a fine of 1,000 yuan for digging out three stems of Cymbidium faberi33, an orchid listed in Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES34; Fig. 3d) but with high market value. Some uncertainty in the legal position regarding herbaceous plants is expressed by another case in the same year, in which an offender was sentenced to one year of imprisonment (fine of 5,000 yuan) for digging out 55 stems of C. faberi35, and the later revocation of the sentences given that C. faberi is not listed in the Catalogue of Wild Plants under Special State Conservation36.

a–d, Wildlife protection laws need to be adaptive to reflect the recovery of formerly threatened species, such as the snow leopard (Panthera uncia; a) or the kiang (E. kiang; b), or the increasing endangerment of initially non-threatened species, such as the butterfly Bhutanitis lidderdalii (c) or the orchid C. faberi (d). Credit: Zhi Lu (a, b); Lixin Zhu (c); Yu Ren (d).

Similar to the non-discrimination of large mammals and insects, we find such an approach also questionable for precious trees and other plants. Such analogies might become almost impossible when applied to algae such as Nostoc flagelliforme, an important water and soil conservation and high-priced food algae but under Class I protection37. The main reason for the lack of quantitative sentencing standards for these organisms is limited evidence. Therefore, we think it is necessary to raise the Regulations of the People’s Republic of China on the Protection of Wild Plants to become law with respective judicial interpretations and to establish comprehensive scientific assessments targeting herbaceous plants, fungi and algae to provide a solid basis for the development of sentencing standards.

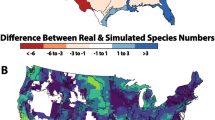

Lack of legislative flexibility to reflect dynamic changes in status and taxonomy

We identified a lack of regular updates of the Catalogues of Wildlife and Wild Plants under Special State Conservation needed to address the dynamic changes in taxonomy and threat status. Since its promulgation, the Wildlife Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China has been revised four times and the Regulations of the People’s Republic of China on the Protection of Wild Plants was amended once in 200138, but the Catalogues of Wildlife and Wild Plants under Special State Conservation have basically remained unchanged for the past 32 and 20 years, respectively, with the exception of a recent amendment of the Catalogue of Wildlife in February 2021 and a pending amendment of the Catalogue of Wild Plants (Box 1). Taxonomies change dynamically, which can lead to considerable incongruences among scientifically accepted species names and those in the respective protection lists39. Until this recent amendment, there has been a mismatch in the names of 25 threatened species as listed under CITES compared with the Catalogue of Wildlife under Special State Conservation, putting them at particular risk because their protection status might be questioned, for example, when species such as the Himalayan goral (Naemorhedus goral), or even genera such as the leaf monkeys (Presbytis spp.), have been split into different units with different names that are not listed in the respective catalogues40. Although the Catalogue of Wildlife under Special State Conservation has been updated very recently, it is still recommended that such updates are done regularly and in a coordinated manner, not only in China but across all CITES signatory nations40.

Additional legislative flexibility is also needed when formerly endangered species have recovered11, while others have become endangered16,41 (Fig. 3). Recently, several mammals such as the giant panda, snow leopards or the kiang (Equus kiang)11,42 have considerably recovered and their threat status has been reduced by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN)11. Although the Chinese government does not follow such a downgrade because of precautionary reasons, we think that the sentencing threshold for such species should be adapted in the Judicial Interpretation of Several Questions Concerning the Application of Law in the Trial of Criminal Cases of Destruction of Wildlife Resources. On the other hand, species whose endangerment has increased since the promulgation of the Catalogues of Wildlife and Wild Plants under Special State Conservation, such as the narrow-ridged finless porpoise43, many birds44, snakes45, turtles46, frogs40, butterflies47 or herbaceous (medicinal) plants2, have long been with low or no protection until the recent amendment. Cultivation can also increase endangerment of wild species by hybridization between the cultivars and the wild populations (for example, rice, wheat, soybean and cotton)48.

Outdated punishment standards based on economic profits

Similar to the lack of flexibility covering species’ taxonomic and threat status, here we highlight that punishment standards are outdated and regular updates are required to reflect economic developments and guarantee balanced sentencing. For instance, according to the Judicial Interpretation of Several Questions Concerning the Application of Law in the Trial of Criminal Cases of Destruction of Wildlife Resources, the illegal purchase, transport and sale of precious and endangered wildlife products will be considered as a ‘serious crime’ if the financial profit is more than 100,000 yuan and as an ‘extremely serious crime’ if the profit is 200,000 yuan or more. The sentencing standard was developed in the year 2000, but with the rapid development of China’s economy, nationwide per capita income has increased more than fourfold from 6,279 yuan in 2000 to 28,228 yuan in 201849. To reflect economic developments, the penalty standards need to be adjusted to comply with the principle of balanced sentencing. In comparison, the Chinese standards for corruption and bribery have been increased from 4,886 yuan in 1997 to currently 30,715 yuan for crimes involving a ‘relatively large amount’, which might serve as a guideline for adapting the sentencing standards for wildlife protection50.

Potential for excessive punishment because of non-discrimination between organized and individual wildlife crime

In this section, we highlight that ignoring the motivational, educational and economic backgrounds of offenders is against the principle of proportionality and may lead to inappropriate deterrence strategies. China’s laws are very strict with quite harsh penalty sentencing; for example, 10.5 years’ imprisonment and a fine of 10,000 yuan for a student taking birds26, 12 years and a fine of 10,000 yuan for a farmer killing a giant panda51 or 13 years and a fine of 2,000 yuan for a farmer taking butterflies20, all cases representing ‘extremely serious crimes’ with a minimum sentencing standard of 10 years’ imprisonment (no maximum defined). Even in comparison with other criminal fields in China and internationally, these standards seem very stringent. For instance, sentences of more than 10 years’ imprisonment apply to larceny only if the value of the stolen goods is larger than 500,000 yuan, or to the theft of first-class cultural relics (all valued in the millions; Criminal Law of the People’s Republic of China, Article 264). Also in comparison, the United Nations Convention Against Transnational Organized Crime52 defines much lower sentencing standards, with at least four years’ imprisonment for a ‘serious crime’. In contrast to China, the wildlife protection laws of Western and many other developing countries prioritize monetary fines over imprisonment. Under European wildlife law53, for example, hunting or destroying Class I protected species is generally punishable by a fine and will be sentenced with fixed-term imprisonment only if the case is ‘extremely serious’. In the United States, the maximum imprisonment is a year, with fines of up to US$50,000 (340,000 yuan)54; in the UK, 6 months and fines of up to £20,000 (177,000 yuan)55,56; in India, 3–7 years and a minimum fine of 25,000 rupees (2,300 yuan)57; or in Brazil, 3 months to a year plus fines58.

The wildlife protection laws of such countries may provide useful examples for China, but to adhere to the principle of proportionality, motivational, educational and economic backgrounds, in particular a differentiation between organized wildlife crimes and individual violations needs to be considered. Individual and organized crimes are currently not differentiated in the Criminal Law of the People’s Republic of China. Historically, wildlife crime was considered a local activity performed by single individuals. However, at present criminal networks are highly involved59 and resulting economic damage from environmental crime has been estimated to range between US$91 billion and US$259 billion globally60, with the profits of illegal wildlife trade ranging between US$7 billion and US$23 billion61, which is of similar orders to human trafficking, and arms and drug dealing62. In China, the consumption of illegal wildlife products has increased with growing economic wealth63, while China has also been identified as one of the major exporters of such products64. Key players in both cases are organized crime groups65,66, causing severe ecological damage while making enormous financial profits67. In such cases, high fines might be simply factored in as part of the ‘business model’. Thus, the current focus on severe jail sentences seems appropriate, and the level is comparable to other Southeast Asian countries (Indonesia: 10 years; Singapore: 2 years; Thailand: 7 years; Vietnam: 15 years)68,69.

In contrast to organized wildlife crime, we also noticed that many cases of harvesting or poaching protected wildlife happened in remote and less-developed regions, conducted by individuals seeking to earn some extra income but without good knowledge of the protection laws20,51. The resulting ecological damage and profits gained are much lower compared with cases of organized wildlife crime, and thus applying the same harsh punishments, as shown in our earlier examples, is clearly against the principle of proportionality. Moreover, it has been shown that the mentality of different types of offender and how they perceive different punishments (imprisonment, fines or both) need to be considered for designing appropriate deterrence strategies for different offence categories, suggesting that imprisonment as the main policy instrument is inappropriate70. Imprisonment is not necessarily a deterrent for every offender, especially when the price of time in prison falls relative to the price of time outside71. Consequently, a penalty that eliminates any financial gain should eliminate the incentive to engage in such conduct72. A shift in focus from imprisonment to fines, at best coupled with local or regional GDP per capita and in combination with raising public awareness, might not only increase proportionality and effectiveness of environmental laws but also comply with other international standards, where, for example, the Council of Europe’s Recommendation (92)17, concerning consistency in sentencing, paragraph B5(2), states that “custodial sentences should be regarded as a sanction of last resort, and should therefore be imposed only in cases where, taking due account of other relevant circumstances, the seriousness of the offence would make any other sentence clearly inadequate”.

Recommendations for improvement

The Chinese government has recognized the risks of biodiversity decline and the importance of its conservation, and international expectations that China will take a prominent role are high73. The recent decision of the National People’s Congress of China to ban trade and consumption of wildlife, to curb the spread of the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-274, also bears great potential for nationwide wildlife protection by amendments to the respective laws. These developments provide the unique opportunity to considerably strengthen the legislative framework for effective wildlife and biodiversity protection in China, while simultaneously avoiding overly harsh sentencing and providing reference for the protection of biodiversity in the world, reflecting international responsibility.

To this end, we recommend the establishment of a committee comprising scientists, environmental lawyers and government agencies to identify ways to strengthen the existing laws. This committee should work in close collaboration with other institutions such as the IPBES, national and international non-governmental organizations (for example, the World Wildlife Fund) or the IUCN (for example, the World Commission on Environmental Law) to elaborate the benefits and potential implementation of the following recommendations. First, we recommend enhancing the use of scientific evidence for threat status assessments by applying international standards, such as those provided by the IUCN Red Lists. We acknowledge a precautionary principle for data-deficient species, but these gaps should be closed as much as possible to avoid unnecessarily harsh punishment. We suggest an expansion of threat assessments to include herbaceous plants, fungi and algae, and adoption of the respective sentencing criteria in the Criminal Law of the People’s Republic of China and the Judicial Interpretation of Several Questions Concerning the Specific Application of Law in the Trial of Criminal Cases of Destruction of Forest Resources. We also recommend more flexibility in the categorization of species to account for dynamic changes in status, such as those that occur via targeted monitoring, and taxonomy. This would need to be achieved in collaboration with the IUCN Red List and CITES as a basis to regularly adjust the Catalogues of Wildlife and Wild Plants under Special State Conservation. We further suggest accounting better for ecological differences among the species groups and ensuing ecological damage, financial profit gained, and, where possible, socioeconomic damage for more proportional sentencing. This would need respective revision of almost all the relevant laws and regulations detailed in Box 1. We also recommend binding sentencing standards to overall economic developments, considering local or regional differences in GDP per capita, with regular updates of the Wildlife Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China, the Criminal Law of the People’s Republic of China and the respective judicial interpretations. Furthermore, we suggest differentiating punishment between organized and individual crimes, with a preference for custodial sentences for the former and monetary fines for the latter, to comply better with international standards by revising the Wildlife Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China, the Criminal Law of the People’s Republic of China and the respective judicial interpretations. Finally, we recommend improving public knowledge about the protected species and related penalties as a responsibility of local governments but in collaboration with national and international non-governmental organizations.

References

Díaz, S. et al. Summary for Policy Makers of the Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services of the Intergovernmental Science–Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES Secretariat, 2019).

Gao, J., Xue, D. & Ma, K. (eds) China’s Biodiversity: A Country Study (Environmental Publishing Group of China, 2017).

Ministry of Forestry of China National Forestry Historical Data, 1950–1953 (Forestry Press of China, 1956).

National Bureau of Statistics of China China Statistical Year Book (Statistic Press of China, 2018).

Results of the Second National Wetland Resources Survey. People’s Daily (14 January 2014); http://env.people.com.cn/n/2014/0114/c1010-24110911.html

Zhang, Y. & Zhou, J. Grassland status and productivity improvement in China. Democr. Sci. 172, 26–28 (2018).

Li, B., Jia, Z., Pan, R. & Ren, B. in Primates in Fragments (ed. Marsh, L. K.) 29–51 (Springer, 2003).

Turvey, S. T. et al. First human-caused extinction of a cetacean species? Biol. Lett. 3, 537–540 (2007).

Zhang, H. et al. Extinction of one of the world’s largest freshwater fishes: lessens for conserving the endangered Yangtze fauna. Sci. Total Environ. 710, 136242 (2020).

Zu, X. How the wild South China tiger endangered - the hope of protection and rescue of South China tiger. Sichuan J. Zool. 22, 190–184 (2003).

The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2020-2 (IUCN, 2020); https://www.iucnredlist.org

Gao, E., Yu, D. & Li, Q. Current situation and protection measures of musk resources in China. Forest Resour. Manag. 1, 33–47 (2005).

Ministry of Environmental Protection, Chinese Academy of Sciences Red List of Biodiversity in China - Higher Plant Volume (Environmental Press, 2013).

Liu, J. et al. Forest fragmentation in China and its effect on biodiversity. Biol. Rev. 94, 1636–1657 (2019).

Xu, Y. et al. Tropical birds are declining in the Hainan island of China. Biol. Conserv. 210, 9–18 (2017).

Liu, X., Qin, J., Xu, Y., Ouyang, S. & Wu, X. Biodiversity decline of fish assemblages after the impoundment of the Three Gorges Dam in the Yangtze River basin, China. Rev. Fish. Biol. Fish. 29, 177–195 (2019).

Yang, R. et al. Transformative changes and paths toward biodiversity conservation in China. Biodivers. Sci. 27, 1032–1040 (2019).

Wang, W., Feng, C., Liu, F. & Li, J. Biodiversity conservation in China: a review of recent studies and practices. Environ. Sci. Ecotechnol. 2, 100025 (2020).

Sun, Y. Research on rule of law guarantee of the mainstreaming biodiversity conservation. J. CUPL 5, 38–49 (2019).

Criminal Judgement Jinxiu Yao Judicial Criminal First Instance Document No.38 (People’s Court of Jinxiu autonomus County, 2002).

Zeng, J., Zhou, S., Luo, B., Tan, K. & Liang, Y. Morphology and bionomics of the endangered butterfly golden Kaiser-i-Hind, Teinopalpus aureus. Chin. Bull. Entomol. 45, 457–464 (2008).

Igarashi, S. Life history of Teinopalpus aureus in Vietnam in comparison with T. imperialis. Butterflies 30, 4–23 (2001).

Zhou, et al. in Research on the Ecology of Fauna and Flora in Guangxi (eds Liang, S. & Ma, J.) 101–103 (Forestry Press of China, 2013).

Li, X. et al. Evidence-based environmental laws for China. Science 341, 958 (2013).

Berlin Zoo will welcome a pair of giant pandas with an annual rent of about one million dollars. Global Network (4 May 2016); https://world.huanqiu.com/article/9CaKrnJV8F1

Criminal Judgement Hui Xingchu No.409 (People’s Court of Huixian City, 2014).

Xue, L., Li, Y. & Meng, X. Some ecological data of Falcon subbuteo. Sichuan J. Zool. 12, 41–42 (1993).

Hiron, M., Pärt, T., Siriwardena, G. M. & Whittingham, M. J. Species contributions to single biodiversity values under-estimate whole community contribution to a wider range of values to society. Sci. Rep. 8, 7004 (2018).

Ouyang, F., Wang, L., Yan, Z., Men, X. & Ge, F. Evaluation of insect pollination and service value in China’s agricultural ecosystem. Acta Ecol. Sinica 39, 131–145 (2019).

Wei, F. et al. The value of ecosystem services from giant panda reserves. Curr. Biol. 28, 2174–2180.e7 (2018).

Cara Donna, P. J. & Waser, N. M. Temporal flexibility in the structure of plant–pollinator interaction networks. Oikos 129, 1369–1380 (2020).

Schleuning, M. et al. Ecological networks are more sensitive to plant than to animal extinction under climate change. Nat. Commun. 7, 13965 (2016).

Criminal Judgement Henan Judicial Criminal First Instance Document, Xingchu No. 209, Yu No. 1224 (Lushi County People’s Court, 2016).

Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora Appendix I, II (IUCN, 1973).

Criminal Judgement Henan Judicial Criminal First Instance Document, Xingchu No.171, Yu No. 1224 (Lushi County People’s Court, 2016).

Criminal Judgement Xingshen No. 4, Yu No. 1224 Re-Trial Decision (Lushi County People’s Court, 2018).

Tang, J., Zhao, M., Zhang, D. & Zhang, J. Biological characteristics and resource protection of Nostoc flagelliforme. Chin. Wild Plant Resour. 19, 20–24 (2000).

Revision on the Regulations on the Protection of Wild Plants of China Decree No. 687 (State Council, 2017).

Zhou, Z. Outdated listing puts species at risk. Nature 525, 187–187 (2015).

Zhou, Z. et al. Revised taxonomic binomials jeopardize protective legislation. Conserv. Lett. 9, 313–315 (2016).

Dai, J. et al. Decline of farmland and pond frogs in thirteen provinces in China. J. Nanjing Norm. Univ. 34, 80–85 (2011).

Lu, F. et al. Number and distribution of Tibetan antelope, Tibetan wild donkey and wild yak in Altun Mountain nature reserve. J. Beijing Norm. Univ. 51, 374–381 (2015).

Announcement of the Results of the Ecological Scientific Expedition of the Yangtze Finless Porpoise in 2017 (Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Areas of China, 2018); http://news.sciencenet.cn/htmlnews/2018/9/417176.shtm?id=417176

Chen, S., Fan, S., Lu, Z. & Huang, Q. Conservation and restoration of Zhejiang population of critically endangered birds: Sterna bernsteini. Zhejiang S1, 20–21 (2014).

Li, P., Wang, W. & Lu, X. Snake conservation and sustainable utilization in China: history, status and future. J. Shenyang Norm. Univ. 31, 129–135 (2013).

Chen, J. et al. Research advance on research of Rafetus swinhoei. Mod. Agric. Sci. Technol. 11, 224–226 (2017).

Zhang, Z., Jiang, Z. & Wang, Z. Habitat, life history and oviposition choice of the endangered Bhutan glory swallowtail Bhutanitis lidderdalii (Lepidoptera: Papilionidae) in Yunnan, China. J. Insect Conserv. 23, 921–931 (2020).

Ellstrand, N. C., Prentice, H. C. & Hancock, J. F. Gene flow and introgression from domesticated plants into their wild relatives. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 30, 539–563 (1999).

National Bureau of Statistics of China China Statistical Yearbook (China Statistics Press, 2019).

Interpretation of Several Issues Concerning the Application of Law in Handling Criminal Cases of Corruption and Bribery (Supreme People’s Court and the Supreme People’s Procuratorate, 2016).

Criminal Order Yun 06 Xingzhong (Criminal Ruling Final) No. 152 (Intermediate People’s Court, Zhaotong City, 2016).

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime United Nations Convention Against Transnational Organized Crime and the Protocols Thereto (United Nations, 2004).

Gesetz über Naturschutz und Landschaftspflege: 69, 71, 71a (Deutscher Bundestag, 2009).

Endangered Species Act of 1973 (The 93rd United States Congress, 1973).

Countryside and Rights of Way Act 2000 (UK Parliament, 2000).

The Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 (UK Parliament, 1981).

Wild Life Protection Act, 1972 (Parliament of India, 1972).

Article 32 of the Federal Environmental Crimes Law (Government of Brazil, 1998).

Wyatt, T., van Uhm, D. & Nurse, A. Differentiating criminal networks in the illegal wildlife trade: organized, corporate and disorganized crime. Trends Organ. Crime 23, 350–366 (2020).

Gore, M. L. et al. Transnational environmental crime threatens sustainable development. Nat. Sustain. 2, 784–786 (2019).

Nellemann, C. et al. (eds) The Rise of Environmental Crime – A Growing Threat To Natural Resources Peace, Development and Security: A UNEPINTERPOL Rapid Response Assessment (United Nations Environment Programme and RHIPTO Rapid Response–Norwegian Center for Global Analyses, 2016).

Wildlife Crime Worth USD 8–10 Billion Annually, Ranking it Alongside Human Trafficking, Arms and Drug Dealing in Terms of Profits: UNODC Chief (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2014); https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/frontpage/2014/May/wildlife-crime-worth-8-10-billion-annually.html

Zhang, S. X. & Chin, K. Snakeheads, mules, and protective umbrellas: a review of current research on Chinese organized crime. Crime Law Soc. Change 50, 177–195 (2008).

Petrossia, G. A., Pires, S. F. & van Uhm, D. P. An overview of seized illegal wildlife entering the United States. Glob. Crime 17, 181–201 (2016).

van Uhm, D. in Organized Crime and Corruption Across Borders (eds Wing, L. T. et al.) 114–133 (Routledge, 2019).

van Uhm, D. & Wong, R. Establishing trust in the illegal wildlife trade in China. Asian J. Criminol. 14, 23–40 (2019).

TRAFFIC Southeast Asia & van Asch, E. in Transnational Organized Crime in East Asia and the Pacific - A Threat Assessment (eds Lale-Domoz, A. et al.) 75–86 (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2013).

The Illegal Wildlife Trade in Southeast Asia: Institutional Capacities in Indonesia, Singapore (OECD, 2019).

The Illegal Wildlife Trade in Southeast Asia: Institutional Capacities in Indonesia, Singapore, Thailand and Viet Nam (OECD, 2019).

Braslavskiy, E., Doko Tchatoka, F. & Masson, V. The importance of punishment substitutability in criminometric studies. Bull. Econ. Res. 71, 491–507 (2019).

Hylton, K. N. Whom should we punish, and how? Rational incentives and criminal justice reform. William Mary Law Rev. 59, 2513 (2018).

Hylton, K. N. Deterrence and antitrust punishment: firms versus agents. Iowa Law Rev. 100, 2069–2072 (2015).

Mallapaty, S. China takes centre stage in global biodiversity push. Nature 578, 245–346 (2020).

The legislative affairs working committee of the National People’s Congress. Xinhua (24 February 2020); http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2020-02/24/c_138814139.htm

Acknowledgements

X.L. and Y.W. acknowledge support from the Alexander von Humboldt foundation. X.L. was supported by the initial scientific research project of China West Normal University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.L. conceived and designed the study. Y.W., X.L. and O.S. wrote the manuscript. Y.W., Y.L. and O.S. represented the legal, national and international point of view. J.W., H.L., E.G. and J.S. contributed to revising the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Ecology & Evolution thanks Zhiyun Ouyang, Arie Trouwborst, Tianbao Qin and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Li, X., Wang, Y., Luo, Y. et al. Opportunities to improve China’s biodiversity protection laws. Nat Ecol Evol 5, 726–732 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-021-01422-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-021-01422-2