Abstract

Various studies have demonstrated that the two leaflets of cellular membranes interact, potentially through so-called interdigitation between the fatty acyl groups. While the molecular mechanism underlying interleaflet coupling remains to be fully understood, recent results suggest interactions between the very-long-chain sphingolipids in the outer leaflet, and phosphatidylserine PS18:0/18:1 in the inner leaflet, and an important role for cholesterol for these interactions. Here we review the evidence that cross-linking of sphingolipids may result in clustering of phosphatidylserine and transfer of signals to the cytosol. Although much remains to be uncovered, the molecular properties and abundance of PS 18:0/18:1 suggest a unique role for this lipid.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lipids are grouped into different classes mainly based on their head groups, whereas various hydrophobic chains give rise to different species within the class (Table 1 and Fig. 1). It is estimated that cells comprise several thousands lipid species, whereas current mass spectrometry (MS) based analyses allow us to quantify ~1000 species1,2,3. Glycerophospholipids are the main constituents of cell membranes. Their amphiphilic character is due to the hydrophilic head and the hydrophobic fatty acyl tails. Generally referred to as phospholipids, glycerophospholipids can form a bilayer. Cellular membranes are such bilayers, where the hydrophobic tails of the phospholipids are located in the middle of the membrane with the hydrophilic head groups facing the hydrophilic surroundings on both sides. Most phospholipids contain ester-bound fatty acyl groups (although also ether-linked phospholipids are common in most tissues) with 16 or 18 carbon atoms and zero, one or two double bonds in cis configuration. However, other fatty acyl groups like C20:4 (arachidonic acid) and C22:6 (docosahexanoic acid; DHA) are also common in the sn-2 position. In this review much of the emphasis will be put on phosphatidylserine (PS), which is a phospholipid with serine bound via a phosphodiesther linkage to glycerol (Fig. 1). For a new and detailed review article about the diversity of membrane lipid composition, see ref. 4.

Structures of glycerophospholipids and sphingolipids. The lipids shown are PS 18:0/18:1 (top) and SM d18:1/24:0 (bottom). Different head groups are giving rise to the various lipid classes (Table 1) and different fatty acyl groups result in various species within the class. Note that sphingolipids often contain N-amidated fatty acyl groups much longer than those most common in glycerophospholipids. The sphingoid base of SM d18:1/24:0 is highlighted in red. It should be noted that the double bond C18:1 (oleic acid) is in cis configuration and that the double bonds of all fatty acyl groups of phospholipids and sphingolipids have a cis configuration. The structures have been made by using the structure drawing tools available at Lipid Maps (www.lipidmaps.org)

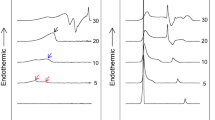

Sphingolipids are also present in cellular membranes but are different from the phospholipids in that their backbone is composed of a sphingoid base (Fig. 1). Whereas the phospholipids are synthesised from glycerol, the sphingolipids are synthesised from serine. The sphingolipids contain N-amidated fatty acyl groups (N originating from serine) that often are much longer than the fatty acyl groups of the phospholipids (Fig. 1). The sphingolipids frequently have a “bimodal” species distribution, meaning that they contain mainly N-amidated C16:0 as the shortest species and C22-C24 as the longest species5,6,7,8,9, with very little present of N-amidated C18 and C20 species. In cells the major sphingolipids species are C16:0, C24:0 or C24:110,11 (more details are given below). The reason for this bimodal distribution is not known. For the purpose of the present discussion it should be noted that C16 and C18 hydrophobic chains are able to reach approximately to the middle of the membrane bilayer, whereas C24 chains are so long that they should be able to reach far into the opposite layer (Fig. 2) and thus be able to give a larger interleaflet coupling as described below.

Illustration of interdigitation between the two membrane leaflets. a Multicomponent bilayer where SM d18:1/24:0 molecules are shown as yellow sticks with the last eight carbon atoms depicted as red balls. Lipids in the outer leaflet are shown as transparent blue glass, while lipids in the inner leaflet are described as transparent grey glass. For clarity SM d18:1/24:0 molecules are marked only in the central part. b Model for a bilayer with PS 18:0/18:1 and cholesterol in the inner leaflet and SM d18:1/16:0 and cholesterol in the outer leaflet. c Similar to B, but SM d18:1/16:0 has been exchanged with SM d18:1/24:0. Blue colour is used for the outer leaflet and yellow for the inner monolayer. Note that the N-amidated fatty acyl group med 24 carbon atoms (in C) are penetrating deeper into the opposite leaflet than the species with 16 carbon atoms (in b). For more details see ref. 52, from where this figure is reproduced

The plasma membrane and the concept of interleaflet coupling

The plasma membrane is known to have an asymmetric distribution of lipids between the two leaflets. Almost all sphingolipids and phosphatidylcholine (PC), a phospholipid with a choline headgroup, are present in the outer leaflet, whereas most of the other plasma membrane phospholipids, such as phosphatidylserine (PS), phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) and phosphatidylinositol (PI), are present in the cytosolic leaflet. It should be noted that cholesterol constitutes 30–40% of all lipids in the plasma membrane. The distribution of cholesterol between the two leaflets have been heavily discussed for many years, but recent data indicate that it is close to evenly distributed in the two leaflets. Although a lot of information about the intracellular distribution of lipids is available1, there is still much to learn about both the distribution of the different lipid classes and their species. As discussed in this review there are several lines of evidence for interactions between the two membrane leaflets in cells and the importance of the length of fatty acyl chains (Fig. 2). Here we discuss the available data relating to transmembrane coupling of lipids (the interaction between fatty acyl chains originating from the two opposing leaflets) and its importance for different cellular processes. We especially focus on the evidence suggesting that the phosphatidylserine species PS 18:0/18:1 play a singular role for membrane function.

Signalling through ligand binding to the outer leaflet

Membrane domains with a high lipid order, including lipid rafts (often referred to as membrane rafts) have been reported to show interactions between the two membrane leaflets and to be important for transmembrane signalling, endocytosis and intracellular transport12,13,14,15,16,17. Such domains are enriched in cholesterol and glycosphingolipids which as mentioned above often have long fatty acyl chains, thus facilitating interactions with the inner leaflet. The binding of multivalent bacterial toxins to glycosphingolipid receptors on host cells results in intracellular signalling18,19,20,21,22,23. This raises the question of how binding of a protein toxin to lipids in the extracellular leaflet of the plasma membrane could result in signalling on the other side of the membrane. One possibility is that toxin-induced signalling is due to cross-linking and clustering of glycolipids.

The bacterially produced Shiga toxin (Stx) and cholera toxin, so called AB5 toxins, contain one enzymatically active A-chain and five B-chains binding to glycosphingolipids on the host cell’s outer membrane. Stx has three binding sites for globotriaosylceramides (Gb3) on each B-chain, but it is not known how many of these binding sites that normally are occupied when Shiga toxin is bound to cells. In contrast, the five B-chains of cholera toxin each bind one monosialotetrahexosylganglioside (GM1); for reviews see24,25,26,27. Also, the SV40 virus multivalently binds to GM128, and there are additionally several toxins and viruses that require glycosphingolipids to interact with cells and induce signalling29.

Consistent with the idea that toxin-induced signalling is due to cross-linking of glycosphingolipids on the plasma membrane, cross-linking of these lipids with antibodies or lectins results in a similar signalling30,31,32. Several possibilities exist for how this might occur. (i) An unknown transmembrane protein could be interacting with the toxins and be involved in this signalling, somewhat similar to what is known for many protein receptors in the plasma membrane. However, no such protein has yet been identified for Stx binding to Gb3 at the cell surface. (ii) The sphingolipids often contain a high fraction of very-long-chain N-amidated fatty acyl groups, e.g. with 22–24 carbon atoms, such that they theoretically should be able to penetrate almost halfway into the inner leaflet. The toxin-induced binding and clustering of these very-long-chain sphingolipids in the outer leaflet by interleaflet coupling could therefore cluster lipids such as PS or phosphorylated phosphatidylinositols (PIPs)11,33,34 in the inner leaflet. The accumulation of PS or PIPs would in turn provide an increased avidity for binding of cytosolic proteins and thus possibly initiate a signalling cascade. (iii) The multivalent binding of these toxins to the cell by cross-linking of lipids could change the conformation of a transmembrane protein, and create Ca-channels resulting in intracellular signalling and downstream effects. In such a scenario, transbilayer coupling may be required.

Cholera toxin might trigger intracellular signalling via multiple pathways, since it can also bind to surface glycoproteins35,36,37. Furthermore, GM1 is able to interact with membrane proteins38. Thus, we will focus on Shiga toxin binding to its lipid receptor Gb3 to provide a basis for discussing interleaflet coupling.

How Stx triggers intracellular signalling

Gb3, the lipid receptor for Stx, consists of a mixture of species with different N-amidated fatty acyl groups containing mainly between 16 and 26 carbon atoms8. The length of the N-amidated fatty acyl groups of Gb3 has been suggested to play a role not only in the binding to Gb325, but also for transport of Stx to the Golgi apparatus and for the Stx toxicity on cells39,40,41,42. Thus, there may be a communication between Gb3 in the outer leaflet and the sorting machinery at the cytosolic side of the plasma membrane, e.g., due to interleaflet coupling between Gb3 and lipids in the inner leaflet.

Theoretically, a high fraction of the Gb3 species should be able to reach approximately halfway into the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane and thus contribute to interleaflet coupling8. It should be noted that the dominant Gb3 species (C24:1) in HEp-2 cells is the only major Gb3 species with a double bond10,43. Since C24:1 (nervonic acid; cis-15) has its double bond between carbon atoms 15 and 16, the double bond of Gb3 d18:1/24:1 will be almost exactly at the centre of the membrane bilayer. Why do biological membranes contain such high amounts of very-long-chain sphingolipids, including one with a double bond placed close to the middle of the bilayer? We speculate that the bimodal distribution of sphingolipids species (mainly C16:0 and the much longer C22:0, C24:0 and C24:1) in cells is important to have such lipids reaching both to the centre of the double layer and far into the other leaflet, thereby creating flexibility for interactions of different strengths between sphingolipids in one leaflet with lipids in the other leaflet.

Gb3 is found both in detergent resistant membranes (DRMs) and non-DRM membrane fractions of many cell lines44. Although DRMs as a tool to study lipid rafts is under debate45, the lipid composition of DRMs may to some extent reflect the composition in lipid rafts. Different studies, including studies using DRMs, indicate that Gb3 present in high lipid-order membrane fractions such as lipid rafts are involved in retrograde transport (i.e., transport to the Golgi apparatus and ER) and toxicity of Stx following transport of the A-chain to cytosol25,41. In particular, nanodomains containing cholesterol were reported to be important for the Stx induced intracellular signalling18 since addition of filipin (which binds to cholesterol) had an inhibitory effect, and extraction of cholesterol with methyl-β-cyclodextrin reduced Golgi transport of Stx46. One can, however, not exclude that such treatments have unspecific effects.

Interleaflet coupling between sphingolipids and PS

While many proteins span the membrane bilayer and are important for its stability, we will focus on interleaflet coupling due to the less well understood interactions between lipids in the two leaflets47,48. Those interactions are often investigated using model membranes lacking the complexity and asymmetry of biological membranes. To our knowledge the first study where quantification of many lipid species of biological membranes was followed up with molecular simulation, was the investigation of exosomes released from PC-3 cells11. Exosomes are small extracellular vesicles released from cells upon fusion of multivesicular bodies (late endosomes) with the plasma membrane. Mass spectrometry (MS) analyses of PC-3 cells and exosomes released from these cells, revealed that cholesterol—the very-long-chain SM species (mainly SM d18:1/24:0 and SM d18:1/24:1) and PS 18:0/18:1 (which is the main PS species making up ~40% of PS species in these exosomes)—were enriched to a very similar extent between cells and exosomes. Furthermore, if one compensates for the different surface areas of the inner and outer leaflet of exosomes with a diameter of 70 nm, PS constitutes approximately half of the phospholipids of the inner leaflet, and PS 18:0/18:1 in the inner leaflet could theoretically cover ~80% of the area covered by the very-long-chain sphingolipids (mainly SM) in the outer leaflet11. These data lead to the idea that these lipids might be sorted together due to interactions (“hand-shaking”) between the very-long-chain SM in the outer leaflet and the PS 18:0/18:1 in the inner leaflet11.

A follow up study performed with PC-3 cells treated with the ether lipid precursor hexadecylglycerol resulted in major changes in the cell lipids, including large increases in the ether lipids. The exosomes released from these cells still had a similar ratio of PS 18:0/18:1 to the very-long-chain SM as in exosomes isolated from untreated cells49. Furthermore, a recent study of exosomes purified from urine of 15 prostate cancer patients and 13 healthy volunteers50 revealed a lipid composition different from that observed in PC-3 cells, but PS 18:0/18:1 in the inner leaflet could still theoretically occupy 78 ± 18% (mean ± SD) and 66 ± 22% of the area covered by the very-long-chain sphingolipids in the outer leaflet in patients and controls, respectively50. It should be noted that the cholesterol content has been reported to be above 40% of total lipids in several exosome preparations45. In the studies discussed above the cholesterol content was 44% of total lipids in exosomes released from PC-3 cells11 and 63% of total lipids in the urinary exosomes50. The last number is close to the maximum solubility reported for cholesterol in model membranes51.

As mentioned above, initial molecular dynamic simulation studies indicated a hand-shaking between the very-long-chain (C24) SM species and PS 18:0/18:111. Later, a simulation study using 14 asymmetric lipid membranes52, demonstrated that in asymmetric models the very-long-chain N-amidated fatty acyl groups of SM were able to penetrate deeply into the inner leaflet. Interestingly, the conformational order of these amide-linked acyl chains was found to increase as they penetrated into the opposing leaflet, revealing that the acyl chains interact with lipids in the inner leaflet. Furthermore, cholesterol was shown to modulate the effect of SM interdigitation by influencing the conformational order of lipid chains in the inner leaflet52. The strongest interdigitation was observed between SM d18:0/24:0 and PS 18:0/18:1 (it should be noted that also PS 16:0/18:1 was included in that study). Notably, the interaction between these two species was the only one that increased in the presence of cholesterol. The strongest interdigitation was observed when there was a little more cholesterol in the SM containing leaflet than in the inner leaflet52.

The lipidomic analyses and the molecular dynamic simulation studies discussed above suggest a co-sorting and hand-shaking between the sphingolipids in the outer leaflet and PS 18:0/18:1 in the inner leaflet of exosomes. The fact that PS 18:0/18:1 is a major lipid species in exosomes excreted from many cell types led us to propose the model shown in Fig. 3, and investigate the membrane composition of other structures. It turns out that there are major similarities between the lipid composition of exosomes, HIV particles and DRMs45, and there is a high enrichment of PS, SM and cholesterol from the mother cell to both the HIV particles53 and the DRMs54,55. Moreover, PS 18:0/18:1 was the dominant PS in these preparations (PS 36:1 quantified in the HIV particles)53. Assuming that HIV particles have a diameter of 120 nm53, the PS 36:1 in the inner leaflet could theoretically cover ~60% of the very-long-chain sphingolipids in the outer leaflet, indicating that there could be a similar hand-shaking between the very-long-chain sphingolipids and PS 18:0/18:1 also in HIV particles45. It has for many years been stated that DRMs are highly enriched in saturated phospholipids. This may be due to the fact that DRMs used in an early and detailed study of their lipid composition were reported to be enriched in saturated phospholipids, the caveat that “a phospholipid was deemed saturated if containing no more than one double bond”55 might often be overlooked. It should also be noted that recycling endosomes have been shown to be enriched in SM, PS and cholesterol, but lipid species were not reported in that study56.

Schematic model of the lipid bilayer of exosomes. The number of lipid molecules (excluding cholesterol) shown in the outer (29) and inner (21) leaflet is close to the ratio for the outer and inner surface of exosomes with a diameter of 70 nm. The lipid composition of the membrane in this simplified illustration is based on the quantitative lipidomic data reported for 22 lipid classes of exosomes excreted from PC-3 cells11, i.e.,16 SM, 13 PC, 12 PS, 6 PE, 3 PE O (PE ethers) and 39 molecules of cholesterol (assuming a close to symmetric distribution of cholesterol between the two leaflets). In the right part of the membrane, a possible handshaking between the very-long-chain sphingolipids in the outer leaflet and PS 18:0/18:1 in the inner leaflet in the presence of cholesterol is illustrated. In the rest of the membrane, the lipids are distributed more or less evenly. Nine out of the 16 SM molecules shown contain a very-long-chain N-amidated fatty acyl group in accordance with the data published11. The figure is reproduced from ref. 45

In summary, it appears that interaction between long-chain and especially the very-long-chain sphingolipids in one leaflet and PS 18:0/18:1 in the opposing leaflet is important for cellular membranes, not only for exosomes. Data showing interactions between PS 18:0/18:1 and cholesterol57 are discussed below. One may wonder why C18:1 (oleic acid; cis-9) in PS seems to be important for such interactions. Is this due to the fact that this double bound is located approximately in the middle of the inner leaflet, and close to the end of the very-long-chain N-amidated fatty acyl group penetrating from the other leaflet? Is the position of this double bound also important for cholesterol induced packing of cell membranes? It should be noted that cells contain much more PS 18:0/18:1 than e.g. PS 16:0/18:1 or PS 18:0/16:1 (Table 2).

Clustering of PS in one membrane leaflet

To our knowledge, a study published in 2011 was the first to indicate a possible interaction between sphingolipids in the outer leaflet and PS in the inner leaflet. The groups of Grinstein and Parton demonstrated topologically distinct cellular pools of PS58, using a PS-binding fluorescent probe and light microscopy, as well as electron microscopy (EM) after gold immune-labelling of this probe. They showed that PS on the cytosolic side of the plasma membrane forms clusters with a diameter of ~11 nm. PS clusters were also observed at the trans-Golgi network and at endocytic organelles. Importantly, PS clusters were observed at 60–80 nm vesicular profiles with the morphology of caveolae, which are known to be enriched in sphingolipids and cholesterol and can be regarded as raft-like structures9,59. Very recently another study showed that PS in fact dictates the assembly and dynamics of caveolae, indicating that membrane leaflet coupling is a prerequisite for their formation60. Grinstein and colleagues also showed that polarisation of PS into the bud of Saccharomyces cerevisiae was required for proper Cdc42 localisation and for development of cell polarity61. However, whether this polarisation is associated with membrane leaflet coupling has to our knowledge not been investigated.

Clustering of PS in the inner leaflet and coupling to GPI

The Mayor group has shown that glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored proteins (GPI-AP) could form nanoscale domains in living cell membranes62. More recently the same group (Raghupathy et al.) reported clustering and interaction between analogues of GPI-AP in the outer leaflet and PS in the inner leaflet of the Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cell line PSA3, which carries a mutation in the PS synthase 1 gene63. Most of the reported experiments were performed using synthetic fluorescent GPI-AP analogues carrying glucosamine inositol linked phosphatidic acid (PA) with a fluorescent label linked to glucosamine, i.e. without any protein part. The clustering of the GPI analogue was reduced when cholesterol was extracted with methyl-β-cyclodextrin or by disrupting actin activity. Based on these data the authors concluded that both cholesterol and actin were important for this clustering63. In such experiments, it is however difficult to exclude that removal of cholesterol induces secondary effects that might be affecting the clustering. The clustering was observed when the lipid part of the GPI analogue contained two saturated long-chain fatty acyl chains (16:0/16:0 and 18:0/18:0 were used), but not when it contained two unsaturated (18:1/18:1) or short chains (8:0/8:0). Thus, the clustering was observed with GPI-AP analogues having fatty acyl chains close to those found in mature endogenous GPI-APs which contains an alkyl chain in the sn-1 position64. Moreover, Raghupathy et al.63 showed that PS in the inner leaflet was required for this clustering, whereas PI(4,5)P2 was shown not to be involved.

By using a protein construct that connect PS to actin they could recruit endogenous GPI-APs in the outer leaflet, thus indicating that actin filaments at the inner leaflet have the capacity to link to PS and immobilise and stabilise local lipid-ordered domains in the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane63. There are some similarities between those observations and some earlier reports that cross-linking of GPI-AP resulted in a cholesterol-dependent intracellular signalling33,65.

As mentioned above, it has for many years been assumed that phospholipid species in rafts mainly contain saturated fatty acyl groups, and in most of the studies performed by Raghupathy et al.63 they compared the results obtained using PS with two saturated fatty acyl groups with those obtained with PS 18:1/18:1. Atomistic molecular dynamic simulation studies with asymmetric bilayers (GPI-analogues in one leaflet and PS species in the other leaflet) showed the strongest transbilayer interdigitation obtained with the GPI analogue carrying two fatty acyl groups with C16:0 and with PS 18:0/18:0; the interdigitation was much less when exchanging PS 18:0/18:0 with PS 18:1/18:1 or PS 12:0/12:0. Furthermore, Raghupathy et al.63 studied the effect of different PS species on the GPI-AP clustering; various PS species were added to the medium, and shown to be incorporated into the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane. Also when measuring the clustering of endogenous GPI-AP on the cell surface by adding PS species in the presence of a PLA2 inhibitor, PS 18:0/18:0 was much more effective than PS 18:1/18:1 or PS 12:0/12:063. For these clustering experiments they also added PS 18:0/18:1 as they found PS 36:1 to be the dominant PS species in these cells. Since PS 18:0/18:1 gave a similar effect on clustering of GPI-AP as PS 18:0/18:0, it was concluded that long-chain PS species were needed to obtain this clustering63. As discussed further below, none of the 9 PS species reported to be present in PSA3 cells contained two saturated FAs (Table 2). Raghupathy et al.63 therefore suggested a general mechanism for the generation of cholesterol-dependent and actin-mediated lipid nanoclusters of GPI-APs and long-chain PS species in biological membranes. Their data for clustering of the GPI-AP analogues and PS in the plasma membrane fit well with the proposal of transbilayer coupling of sphingolipids and PS. Although interleaflet coupling was observed with C16 and C18 fatty acyl groups in the GPI-AP study63 and with SM with 16 carbon atoms in the N-amidated fatty acyl group in the exosome study52, much stronger interleaflet coupling was observed in the exosome study with the very-long-chain SM containing 24 carbon atoms.

PS species found in cells

Considering the role of PS species in interleaflet coupling, it is of interest to quantify PS species in various cell lines. In Table 2 we summarise such data for seven cells lines, including all cell lines discussed in this review, in addition to three other cell types, i.e., MT4 (a human T-cell leukaemia cell line), A549 cells (a human alveolar basal epithelial cell line) and mouse fibroblasts. Furthermore, we have included data for PS 16:0/18:1 as the discussion in the next chapter shows that it is not only the C18:1 in the sn-2 position of PS that is of importance, but also that the length of the saturated fatty acyl group in the sn-1 position plays a role. Table 2 reveals that PS 18:0/18:1 is the dominating PS species in all these cell lines and that there is very little of PS species with two saturated fatty acyl groups. The quantification of other phospholipid classes in the publications listed in Table 2 and other studies reviewed in66, shows very small amounts of lipid species with two saturated fatty acyl groups. Quantitative analyses of lipid species of other cells are warranted to see if the species distribution shown in Table 2 is representative for most cell types. With the present knowledge about lipid species in cells, we conclude that the view that lipid rafts contain large amounts of phospholipids with two saturated fatty acyl groups should be questioned, including recent models containing only saturated PS species in the inner leaflet of rafts17.

The importance of PS 18:0/18:1 and interactions with cholesterol

Maekawa and Fairn57 demonstrated that PS and especially PS18:0/18:1 is important for the proper transbilayer distribution of cholesterol. They used a fluorescent probe, D4H, which recognises cholesterol in the cytosolic leaflet of plasma membrane and organelles. This enabled them to estimate the distribution of cholesterol in the inner and outer leaflet of the plasma membrane of PSB-2 cells. These cells have only 11% of PS synthase activity compared to the CHO cells they were derived from, which resulted in 80% less PS in the PSB-2 cells than in the CHO cells. The transbilayer distribution of cholesterol in the plasma membrane was disturbed in the PSB-2 cells as relatively more cholesterol was present in the outer compared to the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane. The balance between cholesterol in the two leaflets could be normalised by supplementing the medium with PS, but not by adding PE or PC. Thus, their data are consistent with a redistribution of cholesterol from the inner to the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane when the PS level of the plasma membrane is reduced.

These authors also used giant unilamellar liposomes (GUVs) to study phase separation of cholesterol and PS57. Phase separation was achieved when using PS 18:0/18:1, but not when using PS 16:0/18:1, PS 18:1/18:1 or PS 16:0/18:2. Furthermore, PS 18:0/18:1 was the most efficient of these PS species in shielding cholesterol from being oxidised by cholesterol oxidase, and PS 18:0/18:1 also provided a better protection against cholesterol oxidation than egg SM, brain PI(4,5)P2, PC 18:0/18:1, PE 18:0/18:1 and PA 18:0/18:1. Thus, this data represent another example of the importance of PS 18:0/18:1, and indicates a role for interactions between PS 18:0/18:1 and cholesterol57. A summary of data obtained for PS 18:0/18:1 with those obtained for other PS species is given in Table 3.

It was also recently reported that interactions between PS and cholesterol is important for control of membrane curvature67. It was proposed that cholesterol associates with PS to form clusters where the headgroups of PS are sufficiently separated to limit the curvature otherwise caused by the negative charges of PS67. Also, addition of PS 10:0/10:0 was sufficient to increase endocytosis, and removal of cholesterol with methyl-β-cyclodextrin resulted in PS-rich tubules emanating from the plasma membrane67.

PS-binding proteins involvement in transport and signalling

As several lines of evidence support that PS can be clustered in the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane57,58,61,63, one may wonder if PS clustering is important to increase interactions between PS and several cytosolic PS-binding proteins. It should be kept in mind that translocation of proteins from the cytosol to the membrane may depend on the PS density in the binding area, such that it is not only the binding affinity between one PS molecule and the PS-binding protein that is important, but the high avidity created by the accumulated strength of interactions occurring close to each other in the membrane. Also the observation that HeLa cells have a significant fraction of PS with limited mobility, and that cortical actin contributes to the confinement of PS in the plasma membrane68 suggests that “immobilisation” of a fraction of PS could be due to binding of other cytosolic proteins as well. Although several PS-binding proteins are known34,69, more information is needed about this type of proteins and their interaction with PS in order to evaluate their importance for intracellular signalling. A search for proteins (SMART-EMBL database) with pleckstrin homology (PH) domains revealed 259 verified PH-containing proteins and 696 proteins containing the predicted sequences of PH domains thus being candidates for binding to PS. It is not our goal to discuss in detail what is known about PS-binding proteins, but Table 4 contains examples of PS-binding proteins which may contribute to intracellular transport or signalling and perhaps be influenced by PS clustering.

PS in intracellular membranes

Our discussion so far has to a large extent focused on the structure of the plasma membrane, but several of the issues discussed are also relevant for other cell membranes. PS was found in the luminal side of ER, the Golgi complex and mitochondria58, and PS is also exposed to the cytosol during transport from the trans-Golgi to the plasma membrane, as well as in endosomes and lysosomes70. The flipping of PS to the cytosolic leaflet of trans-Golgi has been shown to be due to Arl1 activation of the flippase Drs2 in the trans-Golgi network, and has recently been reviewed71. It should be noted that sphingolipids and cholesterol are selectively enriched in membranes from trans-Golgi to the plasma membrane72,73, and it has been proposed that rafts containing cholesterol and sphingolipids are important for sorting of proteins from the trans-Golgi to the plasma membrane74. Thus, flipping of PS to the cytosolic side of the trans-Golgi71 and interleaflet coupling may be important for sorting of at least of some of these proteins.

For more information about the asymmetry of PS, the importance of flippases, floppases and scramblases as well as other probes for intracellular detection of PS, we refer to the following articles: asymmetry1,13, flippases etc.75,76, and PS-probes75,77. The formation and some functional aspects of PS have recently been reviewed78.

Discussions in the literature about interactions between protein and lipids in the plasma membrane and endosomal vesicles have until now mainly been related to interactions with PIPs. The rapid metabolism of PIPs and their importance for the function of Rab proteins make them suitable for regulating intracellular transport79. The headgroup of PS is not metabolised as fast as PIPs, but on the other hand PS is often present in much higher amounts than the PIPs.

There are examples of PS-binding proteins being important for intracellular transport, e.g., that evectin-2 is important for retrograde transport of cholera toxin from endosomes to the Golgi apparatus80, EHD1 is important for transport through recycling endosomes to the Golgi apparatus, and it has been suggested that EHD1 not only binds to PA but also to PS81. The flippase ATP9A, which is colocalized with PS in early and recycling endosomes, plays a crucial role for recycling from endosomes to the plasma membrane82. Thus, it is clear that PS can play a role for intracellular transport.

Molecular dynamic simulation studies and membrane models

Recently molecular dynamic simulation has proven to be a useful tool to study membrane structures. Although we focused in this review on interleaflet interactions between the very-long-chain sphingolipids and PS 18:0/18:1, it is important to be aware of that interleaflet coupling is found in almost all membrane models. Thus, although we reported the highest interdigitation in asymmetric models with SM d18:1/24:0 and PS 18:0/18:1 in the presence of cholesterol, it should be noticed that interdigitation was measured both when using the shorter SM species with N-amidated C16:0, and with other lipids species and headgroups than PS 18:0/18:152. Although a significant interdigitation has been observed in the symmetric models, a considerably stronger interdigitation was observed when using asymmetric models52, thus stressing the importance of using asymmetric membrane models, i.e. models that are more similar to biological membranes1,13. For more information about simulation studies we refer to recent reviews discussing cholesterol and sphingolipids in raft-like membranes83, the role of charged lipids in membrane structures84, and to two reviews discussing different theories of leaflet coupling and various methods used to study such interactions47,85. Of special interest for the present discussion is that these reviews all stress the importance of using asymmetric models and the ability of the very-long-chain sphingolipids to cross the membrane midplane.

In the two last-mentioned reviews47,85 there are also discussions about the possible contribution of interleaflet coupling due to membrane curvature, line tension, electrostatic interactions and cholesterol flip-flop between membrane leaflets. It has been suggested that the so-called cholesterol flip-flop may give important contributions to the leaflet coupling, but it is argued in the review by Nickels et al.85 that the flip-flop contributes more than a magnitude less than that due to the acyl chain interactions.

Also several interesting studies have been performed using vesicles with an asymmetric membrane. Thus, Chiantia and London86 measured diffusion (using fluorescent correlation spectroscopy) in each membrane leaflet of vesicles containing various SM species in the outer leaflet and various PC species in the inner leaflet. They observed the largest reduction of diffusion in the inner leaflet when using SM C24:0 in the outer one, indicating that this very-long-chain species gave the strongest coupling between the leaflets. The largest reduction of diffusion in the outer leaflet was obtained when the inner leaflet contained PC with one saturated fatty acyl group (either C14, C16 or C18) and one unsaturated fatty acyl group (C18:1)86. They also postulated that van der Waals interactions between the terminal portions of acyl chains from the two leaflets meeting near the midplane is likely to contribute to chain interdigitation effects. Such effects may thus be important for bilayer coupling between membrane areas containing mainly C16 or C18 fatty acyl groups. Later, the same group, using vesicles containing 37% cholesterol and asymmetric membranes with an SM-rich outer leaflet demonstrated the formation of ordered domains in the inner leaflet containing only PC with two unsaturated fatty acyl groups (PC 18:1/18:1)87. Thus, such interactions were demonstrated even with two unsaturated fatty acyl groups in the glycerophospholipids in the inner leaflet, i.e., at conditions expected to be less optimal for such interactions.

The knowledge of making asymmetric liposomes is relatively new and one should expect more studies using such liposomes in the future. It would be useful if one could develop an asymmetric vesicle system with cholesterol, with defined species of both a glycosphingolipid such as Gb3 in the outer leaflet and PS in the inner leaflet and include a reporter kinase to determine whether crosslinking of Gb3 could induce a transmembrane signalling similarly to what was reported by Iwabuchi et al.88.

Despite that asymmetric membrane models are more similar to biological membranes, most studies are still performed with symmetric models containing only one or a few lipid species. Moreover, the lipid species used in such models are often present in very low amounts in cells. These models typically contain identical saturated, monounsaturated or diunsaturated fatty acyl groups, whereas mammalian cells contain high levels of phospholipid species with one saturated and one unsaturated fatty acyl group10,11,66. Even fatty acyl groups much shorter than those found in biological membranes are often used in such models. Thus, a critical discussion of the biological significance of the data obtained in such studies should be included, but are most often lacking. Although the use of giant plasma membrane vesicles have several advantages compared to liposomes regarding similarity with cellular membranes66, it should be noted that these large membrane vesicles have been reported to lose their PS asymmetry89, a change that might affect membrane properties, including interdigitation.

Conclusion

Here we have summarised recent studies which demonstrate coupling between the two leaflets in cellular membranes with a special focus on the importance of the ability of PS 18:0/18:1 present in the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane to interact with very-long-chain sphingolipids in the outer leaflet in a cholesterol dependant manner. The role of coupling between the two membrane leaflets for association with cytosolic proteins and intracellular signalling is discussed. Membrane domains referred to as lipid rafts are often described to be enriched in phospholipid species with two saturated fatty acyl groups. However, such saturated species normally constitute a very small fraction of cellular lipids, and the view that lipid rafts mainly contain phospholipids with two saturated fatty acyl groups should therefore be reconsidered. PS 18:0/18:1 is the major PS species in many cell types and the only species where addition of cholesterol in molecular dynamic simulation studies revealed increased interleaflet coupling with sphingolipids. Although more has to be learnt, the molecular properties and abundance of PS 18:0/18:1 suggest a unique role for this lipid species in cell membranes. Some ideas for future studies in this field are included in Box 1.

References

van Meer, G., Voelker, D. R. & Feigenson, G. W. Membrane lipids: where they are and how they behave. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 112–124 (2008).

Shevchenko, A. & Simons, K. Lipidomics: coming to grips with lipid diversity. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11, 593–598 (2010).

Jung, H. R. et al. High throughput quantitative molecular lipidomics. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1811, 925–934 (2011).

Harayama, T. & Riezman, H. Understanding the diversity of membrane lipid composition. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 19, 281–296 (2018).

Merrill, A. H. Jr. Sphingolipid and glycosphingolipid metabolic pathways in the era of sphingolipidomics. Chem. Rev. 111, 6387–6422 (2011).

Slotte, J. P. Molecular properties of various structurally defined sphingomyelins—Correlation of structure and function. Progr. Lip. Res. 52, 206–219 (2013).

Park, J. W., Park, W. J. & Futerman, A. H. Ceramide synthases as potential targets for therapeutic intervention in human diseases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1841, 671–681 (2014).

Sandvig, K., Bergan, J., Kavaliauskiene, S. & Skotland, T. Lipid requirements for entry of protein toxins into cells. Prog. Lipid Res. 54, 1–13 (2014).

Sonnino, S. & Prinetti, A. Sphingolipids and membrane environments for caveolin. FEBS Lett. 583, 597–606 (2009).

Kavaliauskiene, S. et al. Cell density-induced changes in lipid composition and intracellular trafficking. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 71, 1097–1116 (2014).

Llorente, A. et al. Molecular lipidomics of exosomes released by PC-3 prostate cancer cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1831, 1302–1309 (2013).

Simons, K. & Toomre, D. Lipid rafts and signal transduction. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 1, 31–39 (2000).

Devaux, P. F. & Morris, R. Transmembrane asymmetry and lateral domains in biological membranes. Traffic 5, 241–246 (2004).

Lingwood, D. & Simons, K. Lipid rafts as a membrane-organizing principle. Science 327, 46–50 (2010).

Suzuki, K. G. Lipid rafts generate digital-like signal transduction in cell plasma membranes. Biotechnol. J. 7, 753–761 (2012).

Varshney, P., Yadav, V. & Saini, N. Lipid rafts in immune signalling: current progress and future perspective. Immunology 149, 13–24 (2016).

Sezgin, E., Levental, I., Mayor, S. & Eggeling, C. The mystery of membrane organization: composition, regulation and roles of lipid rafts. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 18, 361–374 (2017).

Katagiri, Y. U. et al. Activation of Src family kinase yes induced by Shiga toxin binding to globotriaosyl ceramide (Gb3/CD77) in low density, detergent-insoluble microdomains. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 35278–35282 (1999).

Takenouchi, H. et al. Shiga toxin binding to globotriaosyl ceramide induces intracellular signals that mediate cytoskeleton remodeling in human renal carcinoma-derived cells. J. Cell Sci. 117, 3911–3922 (2004).

Walchli, S. et al. The Mitogen-activated protein kinase p38 links Shiga Toxin-dependent signaling and trafficking. Mol. Biol. Cell 19, 95–104 (2008).

Utskarpen, A. et al. Shiga toxin increases formation of clathrin-coated pits through Syk kinase. PLoS ONE 5, e10944 (2010).

Spiegel, S., Fishman, P. H. & Weber, R. J. Direct evidence that endogenous GM1 ganglioside can mediate thymocyte proliferation. Science 230, 1285–1287 (1985).

Schnitzler, A. C., Burke, J. M. & Wetzler, L. M. Induction of cell signaling events by the cholera toxin B subunit in antigen-presenting cells. Infect. Immun. 75, 3150–3159 (2007).

Simons, K. & Gerl, M. J. Revitalizing membrane rafts: new tools and insights. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11, 688–699 (2010).

Lingwood, C. A. et al. New aspects of the regulation of glycosphingolipid receptor function. Chem. Phys. Lipids 163, 27–35 (2010).

Bergan, J., Dyve Lingelem, A. B., Simm, R., Skotland, T. & Sandvig, K. Shiga toxins. Toxicon 60, 1085–1107 (2012).

Wernick, N. L., Chinnapen, D. J., Cho, J. A. & Lencer, W. I. Cholera toxin: an intracellular journey into the cytosol by way of the endoplasmic reticulum. Toxins 2, 310–325 (2010).

Ewers, H. et al. GM1 structure determines SV40-induced membrane invagination and infection. Nat. Cell Biol. 12, 11–18 (2010).

Russo, D., Parashuraman, S. & D’Angelo, G. Glycosphingolipid-protein interaction in signal transduction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 17, e1732 (2016).

Ravichandra, B. & Joshi, P. G. Regulation of transmembrane signaling by ganglioside GM1: interaction of anti-GM1 with Neuro2a cells. J. Neurochem. 73, 557–567 (1999).

Wang, J. et al. Cross-linking of GM1 ganglioside by galectin-1 mediates regulatory T cell activity involving TRPC5 channel activation: possible role in suppressing experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J. Immunol. 182, 4036–4045 (2009).

Klokk, T. I., Kavaliauskiene, S. & Sandvig, K. Cross-linking of glycosphingolipids at the plasma membrane: consequences for intracellular signaling and traffic. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 73, 1301–1316 (2016).

Chen, Y., Thelin, W. R., Yang, B., Milgram, S. L. & Jacobson, K. Transient anchorage of cross-linked glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol-anchored proteins depends on cholesterol, Src family kinases, caveolin, and phosphoinositides. J. Cell Biol. 175, 169–178 (2006).

Lu, S. M. & Fairn, G. D. Mesoscale organization of domains in the plasma membrane—beyond the lipid raft. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 53, 192–207 (2018).

Wands, A. M. et al. Fucosylation and protein glycosylation create functional receptors for cholera toxin. eLife 4, e09545 (2015).

Cervin, J. et al. GM1 ganglioside-independent intoxication by Cholera toxin. PLoS Pathog. 14, e1006862 (2018).

Monferran, C. G., Roth, G. A. & Cumar, F. A. Inhibition of cholera toxin binding to membrane receptors by pig gastric mucin-derived glycopeptides: differential effect depending on the ABO blood group antigenic determinants. Infect. Immun. 58, 3966–3972 (1990).

Ledeen, R. W. & Wu, G. The multi-tasked life of GM1 ganglioside, a true factotum of nature. Trends Biochem. Sci. 40, 407–418 (2015).

Sandvig, K. et al. Retrograde transport of endocytosed Shiga toxin to the endoplasmic reticulum. Nature 358, 510–512 (1992).

Sandvig, K., Garred, O., van Helvoort, A., van Meer, G. & van Deurs, B. Importance of glycolipid synthesis for butyric acid-induced sensitization to shiga toxin and intracellular sorting of toxin in A431 cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 7, 1391–1404 (1996).

Falguieres, T. et al. Functionally different pools of Shiga toxin receptor, globotriaosyl ceramide, in HeLa cells. FEBS J. 273, 5205–5218 (2006).

Arab, S. & Lingwood, C. A. Intracellular targeting of the endoplasmic reticulum/nuclear envelope by retrograde transport may determine cell hypersensitivity to verotoxin via globotriaosyl ceramide fatty acid isoform traffic. J. Cell. Physiol. 177, 646–660 (1998).

Bergan, J. et al. The ether lipid precursor hexadecylglycerol causes major changes in the lipidome of HEp-2 cells. PLoS ONE 8, e75904 (2013).

Legros, N. et al. Colocalization of receptors for Shiga toxins with lipid rafts in primary human renal glomerular endothelial cells and influence of D-PDMP on synthesis and distribution of glycosphingolipid receptors. Glycobiology 27, 947–965 (2017).

Skotland, T., Sandvig, K. & Llorente, A. Lipids in exosomes: current knowledge and the way forward. Prog. Lipid Res. 66, 30–41 (2017).

Falguieres, T. et al. Targeting of Shiga toxin B-subunit to retrograde transport route in association with detergent-resistant membranes. Mol. Biol. Cell. 12, 2453–2468 (2001).

Fujimoto, T. & Parmryd, I. Interleaflet coupling, pinning, and leaflet asymmetry-major players in plasma membrane nanodomain formation. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 4, 155 (2016).

Zhou, Y. & Hancock, J. F. Deciphering lipid codes: K-Ras as a paradigm. Traffic 19, 157–165 (2018).

Phuyal, S. et al. The ether lipid precursor hexadecylglycerol stimulates the release and changes the composition of exosomes derived from PC-3 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 4225–4237 (2015).

Skotland, T. et al. Molecular lipid species in urinary exosomes as potential prostate cancer biomarkers. Eur. J. Cancer 70, 122–132 (2017).

Huang, J., Buboltz, J. T. & Feigenson, G. W. Maximum solubility of cholesterol in phosphatidylcholine and phosphatidylethanolamine bilayers. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1417, 89–100 (1999).

Rog, T. et al. Interdigitation of long-chain sphingomyelin induces coupling of membrane leaflets in a cholesterol dependent manner. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1858, 281–288 (2016).

Lorizate, M. et al. Comparative lipidomics analysis of HIV-1 particles and their producer cell membrane in different cell lines. Cell Microbiol. 15, 292–304 (2013).

Pike, L. J., Han, X., Chung, K. N. & Gross, R. W. Lipid rafts are enriched in arachidonic acid and plasmenylethanolamine and their composition is independent of caveolin-1 expression: a quantitative electrospray ionization/mass spectrometric analysis. Biochemistry 41, 2075–2088 (2002).

Pike, L. J., Han, X. & Gross, R. W. Epidermal growth factor receptors are localized to lipid rafts that contain a balance of inner and outer leaflet lipids: a shotgun lipidomics study. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 26796–26804 (2005).

Gagescu, R. et al. The recycling endosome of Madin-Darby canine kidney cells is a mildly acidic compartment rich in raft components. Mol. Biol. Cell 11, 2775–2791 (2000).

Maekawa, M. & Fairn, G. D. Complementary probes reveal that phosphatidylserine is required for the proper transbilayer distribution of cholesterol. J. Cell Sci. 128, 1422–1433 (2015).

Fairn, G. D. et al. High-resolution mapping reveals topologically distinct cellular pools of phosphatidylserine. J. Cell Biol. 194, 257–275 (2011).

Ortegren, U. et al. Lipids and glycosphingolipids in caveolae and surrounding plasma membrane of primary rat adipocytes. Eur. J. Biochem. 271, 2028–2036 (2004).

Hirama, T. et al. Phosphatidylserine dictates the assembly and dynamics of caveolae in the plasma membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 14292–14307 (2017).

Fairn, G. D., Hermansson, M., Somerharju, P. & Grinstein, S. Phosphatidylserine is polarized and required for proper Cdc42 localization and for development of cell polarity. Nat. Cell Biol. 13, 1424–1430 (2011).

Sharma, P. et al. Nanoscale organization of multiple GPI-anchored proteins in living cell membranes. Cell 116, 577–589 (2004).

Raghupathy, R. et al. Transbilayer lipid interactions mediate nanoclustering of lipid-anchored proteins. Cell 161, 581–594 (2015).

Kinoshita, T. & Fujita, M. Biosynthesis of GPI-anchored proteins: special emphasis on GPI lipid remodeling. J. Lipid Res. 57, 6–24 (2016).

Stefanova, I., Horejsi, V., Ansotegui, I. J., Knapp, W. & Stockinger, H. GPI-anchored cell-surface molecules complexed to protein tyrosine kinases. Science 254, 1016–1019 (1991).

Levental, I. & Veatch, S. The continuing mystery of lipid Rafts. J. Mol. Biol. 428, 4749–4764 (2016).

Hirama, T. et al. Membrane curvature induced by proximity of anionic phospholipids can initiate endocytosis. Nat. Commun. 8, 1393 (2017).

Kay, J. G., Koivusalo, M., Ma, X., Wohland, T. & Grinstein, S. Phosphatidylserine dynamics in cellular membranes. Mol. Biol. Cell. 23, 2198–2212 (2012).

Stace, C. L. & Ktistakis, N. T. Phosphatidic acid- and phosphatidylserine-binding proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1761, 913–926 (2006).

Yeung, T. et al. Membrane phosphatidylserine regulates surface charge and protein localization. Science 319, 210–213 (2008).

Yu, C. J. & Lee, F. J. Multiple activities of Arl1 GTPase in the trans-Golgi network. J. Cell Sci. 130, 1691–1699 (2017).

Klemm, R. W. et al. Segregation of sphingolipids and sterols during formation of secretory vesicles at the trans-Golgi network. J. Cell Biol. 185, 601–612 (2009).

Slotte, J. P. Biological functions of sphingomyelins. Prog. Lipid Res. 52, 424–437 (2013).

Surma, M. A., Klose, C. & Simons, K. Lipid-dependent protein sorting at the trans-Golgi network. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1821, 1059–1067 (2012).

Leventis, P. A. & Grinstein, S. The distribution and function of phosphatidylserine in cellular membranes. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 39, 407–427 (2010).

Hankins, H. M., Baldridge, R. D., Xu, P. & Graham, T. R. Role of flippases, scramblases and transfer proteins in phosphatidylserine subcellular distribution. Traffic 16, 35–47 (2015).

Kay, J. G. & Grinstein, S. Sensing phosphatidylserine in cellular membranes. Sensors 11, 1744–1755 (2011).

Vance, J. E. & Tasseva, G. Formation and function of phosphatidylserine and phosphatidylethanolamine in mammalian cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1831, 543–554 (2013).

Schink, K. O., Tan, K. W. & Stenmark, H. Phosphoinositides in control of membrane dynamics. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 32, 143–171 (2016).

Lee, S. et al. Impaired retrograde membrane traffic through endosomes in a mutant CHO cell defective in phosphatidylserine synthesis. Genes Cells 17, 728–736 (2012).

Lee, S. et al. Transport through recycling endosomes requires EHD1 recruitment by a phosphatidylserine translocase. EMBO J. 34, 669–688 (2015).

Tanaka, Y. et al. The phospholipid flippase ATP9A is required for the recycling pathway from the endosomes to the plasma membrane. Mol. Biol. Cell 27, 3883–3893 (2016).

Rog, T. & Vattulainen, I. Cholesterol, sphingolipids, and glycolipids: what do we know about their role in raft-like membranes? Chem. Phys. Lipids 184, 82–104 (2014).

Poyry, S. & Vattulainen, I. Role of charged lipids in membrane structures—Insight given by simulations. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1858, 2322–2333 (2016).

Nickels, J. D., Smith, J. C. & Cheng, X. Lateral organization, bilayer asymmetry, and inter-leaflet coupling of biological membranes. Chem. Phys. Lipids 192, 87–99 (2015).

Chiantia, S. & London, E. Acyl chain length and saturation modulate interleaflet coupling in asymmetric bilayers: effects on dynamics and structural order. Biophys. J. 103, 2311–2319 (2012).

Lin, Q. & London, E. Ordered raft domains induced by outer leaflet sphingomyelin in cholesterol-rich asymmetric vesicles. Biophys. J. 108, 2212–2222 (2015).

Iwabuchi, K. et al. Reconstitution of membranes simulating “glycosignaling domain” and their susceptibility to lyso-GM3. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 15174–15181 (2000).

Levental, K. R. & Levental, I. Isolation of giant plasma membrane vesicles for evaluation of plasma membrane structure and protein partitioning. Methods Mol. Biol. 1232, 65–77 (2015).

Li, G. et al. Efficient replacement of plasma membrane outer leaflet phospholipids and sphingolipids in cells with exogenous lipids. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 14025–14030 (2016).

Ogiso, H., Taniguchi, M. & Okazaki, T. Analysis of lipid-composition changes in plasma membrane microdomains. J. Lipid Res. 56, 1594–1605 (2015).

Boureux, A., Vignal, E., Faure, S. & Fort, P. Evolution of the Rho family of ras-like GTPases in eukaryotes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24, 203–216 (2007).

Ridley, A. J. Rho GTPase signalling in cell migration. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 36, 103–112 (2015).

Haupt, A. & Minc, N. Gradients of phosphatidylserine contribute to plasma membrane charge localization and cell polarity in fission yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell 28, 210–220 (2017).

Baetz, N. W. & Goldenring, J. R. Distinct patterns of phosphatidylserine localization within the Rab11a-containing recycling system. Cell. Logist. 4, e28680 (2014).

Niv, H., Gutman, O., Kloog, Y. & Henis, Y. I. Activated K-Ras and H-Ras display different interactions with saturable nonraft sites at the surface of live cells. J. Cell Biol. 157, 865–872 (2002).

Jansen, J. M. et al. Inhibition of prenylated KRAS in a lipid environment. PLoS ONE 12, e0174706 (2017).

Cho, K. J. et al. Inhibition of acid sphingomyelinase depletes cellular phosphatidylserine and mislocalizes K-Ras from the plasma membrane. Mol. Cell. Biol. 36, 363–374 (2015).

Newton, A. C. Protein kinase C: structure, function, and regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 28495–28498 (1995).

Huang, B. X., Akbar, M., Kevala, K. & Kim, H. Y. Phosphatidylserine is a critical modulator for Akt activation. J. Cell. Biol. 192, 979–992 (2011).

McKenzie, J. E. et al. Retromer guides STxB and CD8-M6PR from early to recycling endosomes, EHD1 guides STxB from recycling endosome to Golgi. Traffic 13, 1140–1159 (2012).

Zhang, Z., Hui, E., Chapman, E. R. & Jackson, M. B. Regulation of exocytosis and fusion pores by synaptotagmin-effector interactions. Mol. Biol. Cell. 21, 2821–2831 (2010).

Kovtun, O., Tillu, V. A., Ariotti, N., Parton, R. G. & Collins, B. M. Cavin family proteins and the assembly of caveolae. J. Cell. Sci. 128, 1269–1278 (2015).

Stoeber, M. et al. Model for the architecture of caveolae based on a flexible, net-like assembly of Cavin1 and Caveolin discs. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, E8069–E8078 (2016).

Hoop, C. L., Sivanandam, V. N., Kodali, R., Srnec, M. N. & van der Wel, P. C. Structural characterization of the caveolin scaffolding domain in association with cholesterol-rich membranes. Biochemistry 51, 90–99 (2012).

Ariotti, N. et al. Caveolae regulate the nanoscale organization of the plasma membrane to remotely control Ras signaling. J. Cell. Biol. 204, 777–792 (2014).

Mazerik, J. N. & Tyska, M. J. Myosin-1A targets to microvilli using multiple membrane binding motifs in the tail homology 1 (TH1) domain. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 13104–13115 (2012).

An, X., Guo, X., Wu, Y. & Mohandas, N. Phosphatidylserine binding sites in red cell spectrin. Blood. Cells Mol. Dis. 32, 430–432 (2004).

Machnicka, B. et al. Spectrins: a structural platform for stabilization and activation of membrane channels, receptors and transporters. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1838, 620–634 (2014).

Maeda, K. et al. Interactome map uncovers phosphatidylserine transport by oxysterol-binding proteins. Nature 501, 257–261 (2013).

Chung, J. et al. PI4P/phosphatidylserine countertransport at ORP5- and ORP8-mediated ER-plasma membrane contacts. Science 349, 428–432 (2015).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the valuable discussions with Dr. Kim Ekroos and Dr. Ilpo Vattulainen during our collaboration of articles cited in this review. We thank Anders Øverbye for performing the search for PH domains, and Simona Kavaliauskiene for producing Fig. 1. The authors were supported by the Research Council of Norway through the funding scheme NANO2021 (project number 228200/O70), The Norwegian Cancer Society (project number 41889), and the South Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority (project number 2015023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.S. and K.S. co-wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information: Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Skotland, T., Sandvig, K. The role of PS 18:0/18:1 in membrane function. Nat Commun 10, 2752 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-10711-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-10711-1

This article is cited by

-

Phosphatidylserine-exposing extracellular vesicles in body fluids are an innate defence against apoptotic mimicry viral pathogens

Nature Microbiology (2024)

-

Antibody binding reports spatial heterogeneities in cell membrane organization

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Fatty acid fingerprints in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and its extracellular vesicles reflect equine asthma severity

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Lipidomic and Membrane Mechanical Signatures in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: Scope for Membrane-Based Theranostics

Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry (2022)

-

Phospholipid Compositions in Portunus trituberculatus Larvae at Different Developmental Stages

Journal of Ocean University of China (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.