Abstract

Quantum mechanics imposes a limit on the precision of a continuous position measurement of a harmonic oscillator, due to backaction arising from quantum fluctuations in the measurement field. This standard quantum limit can be surpassed by monitoring only one of the two non-commuting quadratures of the motion, known as backaction-evading measurement. This technique has not been implemented using optical interferometers to date. Here we demonstrate, in a cavity optomechanical system operating in the optical domain, a continuous two-tone backaction-evading measurement of a localized gigahertz-frequency mechanical mode of a photonic-crystal nanobeam cryogenically and optomechanically cooled close to the ground state. Employing quantum-limited optical heterodyne detection, we explicitly show the transition from conventional to backaction-evading measurement. We observe up to 0.67 dB (14%) reduction of total measurement noise, thereby demonstrating the viability of backaction-evading measurements in nanomechanical resonators for optical ultrasensitive measurements of motion and force.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In a continuous measurement of the position \(\hat x\) of a harmonic oscillator, quantum backaction (QBA) of the measuring probe on the momentum \(\hat p\) ultimately limits the attainable precision1,2, restricting ultrasensitive measurements of force or motion. For an interferometric position measurement, in which a mechanical oscillator is parametrically coupled to a cavity, the trade-off arising from measurement imprecision (i.e., detector shot noise) and QBA force noise on the mechanical oscillator, dictates a minimum added noise equivalent to the oscillator’s zero-point fluctuations, \(x_{\mathrm{zpf}} = \sqrt {\hbar {\mathrm{/}}2m\Omega_{\mathrm{m}}}\), referred to as the standard quantum limit (SQL), originally studied in the context of gravitational wave detection1,3 (here m is the mass and Ωm the angular frequency of the mechanical oscillator). Recent advances in the field of cavity optomechanics4, which utilizes a nano- or micromechanical oscillator coupled to an optical or superconducting microwave cavity, have allowed reaching the regime where the QBA arising from radiation pressure quantum fluctuations becomes relevant. In particular, imprecision noise far below that at the SQL has been obtained5,6, thus entering the QBA-dominated regime; QBA has been observed7,8,9 and sensitivities approaching the SQL have been demonstrated9,10,11,12.

Quantum non-demolition (QND) techniques, first proposed by Thorne, Braginsky, and colleagues13,14,15, allow beating the SQL by minimizing or evading the effects of QBA. One technique to surpass the SQL, applicable to measurements far from the mechanical resonance frequency Ωm, utilizes quantum correlations in the probe (due to ponderomotive squeezing16,17,18,19), known as “variational readout”20,21. This technique has recently been demonstrated in a cryogenic micromechanical oscillator coupled to an optical cavity22 and in a room-temperature nano-optomechanical system for quantum-enhanced force measurements23. Another possibility is utilizing squeezed light, a technique applied to gravitational wave detectors21,24,25. More recent schemes include measurements of the collective motion in a hybrid system composed either of two mechanical oscillators (as demonstrated for an electromechanical system26,27) or a mechanical and a “negative mass” oscillator (demonstrated using an atomic ensemble28,29).

Another type of QND measurement, backaction-evading (BAE) measurements introduced by Thorne et al.13, allow avoiding QBA entirely by measuring only one of the two slowly varying amplitude and phase quadratures \(\hat X\) and \(\hat Y\), defined by \(\hat x(t) \equiv \sqrt 2 x_{{\mathrm{zpf}}}[\hat X(t)\cos\Omega _{\mathrm{m}}t + \hat Y(t)\sin\Omega _{\mathrm{m}}t]\), which constitute QND observables. Unlike \(\hat x\) and \(\hat p\), the conjugate observables \(\hat X\) and \(\hat Y\) are decoupled from each other during free dynamic evolution. By exclusively measuring \(\hat X\), e.g., all QBA is diverted to \(\hat Y\) and is completely absent from the measurement record. By increasing coupling to the system (probe power), one can then arbitrarily reduce the imprecision noise, allowing in principle unlimited sensitivity in the measurement of one quadrature. In a cavity optomechanical system, such BAE measurement is possible by amplitude-modulating a cavity-resonant probe at frequency Ωm14,15,30, equivalent to two-tone probing on the upper and lower mechanical sidebands of the cavity. It has been pointed out22 that single-quadrature measurement may also be realized using synodyne detection31. Two-tone BAE is applicable in the well-resolved sideband regime \(\Omega _{\mathrm{m}} \gg \kappa\), where \(\kappa\) is the cavity linewidth. In the opposite regime of a fast cavity \(\kappa \gg \Omega _{\mathrm{m}}\), one must resort to stroboscopic QND measurements, requiring interaction times \(\ll \Omega _{\mathrm{m}}^{ - 1}\) (refs 1,14).

To date, such two-tone BAE measurements have exclusively been demonstrated in microwave optomechanical systems32,33, where they have also been utilized to perform tomography of states produced by schemes that produce reservoir-engineered squeezed34,35,36,37,38 and entangled39,40 mechanical states. Yet, in all these experiments, noise resulting from the use of a microwave amplifiers at elevated temperatures resulted in substantially decreased efficiency and hindered beating the SQL33. In addition, thermal noise at microwave frequencies can be non-negligible even at cryogenic temperatures and requires careful calibration41. In contrast, optical homodyne or heterodyne detection is quantum-limited and light is effectively a zero-temperature bath, allowing self-calibrated measurements of motion42,43,44. Optomechanical systems using laser light have demonstrated quantum effects up to room temperature23,45. Despite advances in operating in the QBA-dominated regime in cavity optomechanics, BAE measurements in the optical domain have not been reported.

Here we demonstrate a two-tone BAE measurement in the optical domain of an oscillator in a thermal state, using quantum-limited balanced heterodyne detection (BHD). We observe explicitly the reduction of thermomechanical noise due to cancellation of QBA from the measuring probes. We analyze the effect of extraneous heating due to optical absorption, which limits the attainable sensitivity in the present sample.

Results

Theoretical model

We first consider theoretically the scenario depicted in Fig. 1b–d, in which a cavity optomechanical system is interrogated with two tones detuned by \(\pm (\Omega _{\mathrm{m}} + \delta )\) from the cavity resonance and the two sidebands are detected using BHD. The mechanical oscillator is in a thermal state with mean occupation \(\bar n\). In the case of a quantum-limited laser, in the well-resolved sideband regime \(\Omega _{\mathrm{m}} \gg \kappa\), and within the rotating-wave approximation (RWA), the measured photocurrent power spectral density (PSD) is given by (Methods section)

where \(\chi _{\mathrm{m}}(\omega ) = ( - i\omega + \Gamma _{{\mathrm{eff}}}{\mathrm{/}}2)^{ - 1}\) is the mechanical susceptibility of the oscillator with total mechanical linewidth Γeff, \(\eta\) the overall detection efficiency, and \({\cal{C}} = 4g_0^2n_{\mathrm{p}}{\mathrm{/}}\kappa \Gamma _{{\mathrm{eff}}}\) the optomechanical cooperativity proportional to the input power. Here, g0 is the vacuum optomechanical coupling strength and np the mean number of intracavity photons due to each probe.

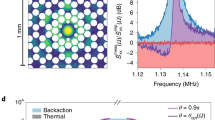

Backaction-evading measurement. a Illustration of a cavity optomechanical system. Light in a cavity with optical resonance ωc and full linewidth κ (of which κi are intrinsic losses) is coupled to the position \(\hat x\) of a mechanical oscillator that has frequency Ωm and linewidth Γm. In a backaction-evading (BAE) measurement, the probe is amplitude-modulated at the mechanical frequency Ωm, coupling to the quadrature \(\hat X\). b Frequency space configuration slightly detuned from BAE measurement, where the probe is modulated at Ωm + δ. c Resulting power spectral density of the cavity output field for an oscillator in a thermal state (mean occupation \(\bar n\)), showing the asymmetric Stokes and anti-Stokes scattered sidebands, plus the heating due to QBA. d When tuning to the BAE scheme δ = 0, the two sidebands coalesce and the QBA is cancelled, see Eq. (1). The remaining imprecision noise \(\overline n _{{\mathrm{imp}}}\) can be arbitrarily reduced by increasing probe power

The PSD in Eq. (1) is normalized to the vacuum noise level, given by the constant 1 in the first term. The first and second terms in brackets correspond to the anti-Stokes and Stokes scattered motional sidebands, respectively, having the Lorentzian shape of the mechanical susceptibility. These exhibit the well-known motional sideband asymmetry2,41,42,43,44,46,47,48, resulting from the ratio \((\bar n + 1){\mathrm{/}}\bar n\) between absorption and emission rates. The last term in brackets is the QBA due to quantum noise in the probe light. When \(\delta \gg \Gamma _{{\mathrm{eff}}}\), QBA appears as heating of the oscillator, adding \(\overline n _{{\mathrm{BA}}} = {\cal{C}}\) mean quanta (Fig. 1c). The two QBA components have opposite phase. When δ = 0, QBA is cancelled, yielding a pristine measurement of the oscillator with PSD \(\bar S_{II}(\omega ) = 1 + \eta \Gamma _{{\mathrm{eff}}}{\cal{C}}\bar S_{XX}(\omega )\) where \(\bar S_{XX}(\omega ) = (\Gamma _{{\mathrm{eff}}}{\mathrm{/}}2)(2\bar n + 1)\left| {\chi _{\mathrm{m}}(\omega )} \right|^2\) is the noise spectral density of quadrature \(\hat X\) (Fig. 1d). In this case, \(2\overline n _{{\mathrm{BA}}}\) quanta are added to the complementary quadrature30 (it is noteworthy that our definition of \(\overline n _{{\mathrm{BA}}}\) is half that of ref. 30, in order to facilitate comparison with conventional position measurement using homodyne detection). In principle, one can then increase signal-to-noise ratio (i.e., measurement sensitivity) indefinitely, with no deleterious effects on the measurement, simply by increasing probing power. In Eq. (1) we have neglected bad-cavity effects where photons scattered out of resonance interact with counter-propagating terms (neglected in the RWA) to induce QBA30, resulting in \(\bar n_{{\mathrm{bad}}} = (\kappa {\mathrm{/}}4\Omega _m)^2{\cal{C}}\) added quanta. In our experiment, \({\cal{C}}\, \lesssim\, 10\) and thus \(\bar n_{{\mathrm{bad}}}\,\, \lesssim\, 10^{ - 2}\) is completely negligible.

Experimental setup

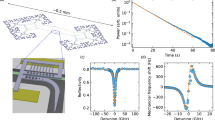

We performed a BAE measurement in a silicon nanobeam optomechanical crystal49, shown in Fig. 2a. Optically, the device functions as a single-sided cavity with a partially transmitting input mirror. Light is evanescently coupled from a tapered optical fiber into a waveguide that forms part of the nanobeam, with a coupling efficiency exceeding 50%. The optical resonance is at 1540 nm with a linewidth of \(\kappa {\mathrm{/}}2\pi = 1.7\,{\mathrm{GHz}}\), of which \(\kappa _{{\mathrm{ex}}} = 0.3\kappa\) are extrinsic losses to the input mirror. The optical mode is optomechanically coupled to a mechanical breathing mode of frequency Ωm/2π = 5.3 GHz, strongly confined due to a phononic bandgap, and an intrinsic linewidth of Γint/2π = 84 kHz. This places the system in the resolved sideband regime50. The optomechanical coupling parameter is g0/2π = 780 kHz. Full details of the device design, the setup, and the system are given elsewhere44.

Optomechanical crystal and experimental setup. a False-color SEM image of the silicon optomechanical crystal cavity with a waveguide for laser input coupling. The path of the tapered fiber is indicated. b SEM image detail of the cavity. c Illustration of the mechanical breathing mode and optical mode. d Experimental setup. AOM, acousto-optical modulator; BHD, balanced heterodyne detector; ECDL, external-cavity diode laser; PLL, phase-locked loop; PM, phase modulator; VOA, variable optical attenuator

The system is placed in a 3He buffer-gas cryostat (Oxford Instruments HelioxTL), allowing cryogenic operation down to 0.5 K. As detailed in ref. 44, the buffer-gas environment allows us to overcome the prohibitive optical absorption heating in vacuo that has limited operation with these devices to very low photon numbers51 or pulsed operation52,53,54,55. We are thus able to operate at high probe powers where QBA is observable. The buffer gas causes additional damping, increasing the mechanical linewidth to Γm = Γint + Γgas. In addition to the BAE probes, we also apply a cooling tone red-detuned from the optical resonance, to lower the thermal occupation \(\bar n\) through optomechanical sideband cooling50, \(\bar n \simeq \bar n_{{\mathrm{th}}}{\mathrm{/}}(1 + {\cal{C}}_{{\mathrm{cool}}})\) with \(\overline n _{{\mathrm{th}}}\) the occupation of the thermal environment. The cooling tone also provides additional damping due to dynamical backaction, \(\Gamma _{{\mathrm{eff}}} = \Gamma _{\mathrm{m}}(1 + {\cal{C}}_{{\mathrm{cool}}})\), which is the effective linewidth seen by the BAE probes. It is noteworthy that the probes, equal in power and oppositely detuned from cavity resonance, do not produce such dynamical backaction. Here, \({\cal{C}}_{{\mathrm{cool}}} = {\cal{C}}_0n_{\mathrm{c}}\) is the cooling tone cooperativity defined similar to \({\cal{C}}\) but relative to the original linewidth Γm, with the single photon cooperativity \({\cal{C}}_0 \equiv 4g_0^2{\mathrm{/}}\kappa \Gamma _{\mathrm{m}}\), and nc the mean intracavity photons due to the cooling tone. The cooling tone is tuned 2π × 220 MHz away from the red-detuned BAE probe to mitigate recently reported Kerr-type effects44.

The experimental setup is shown in Fig. 2d. The two BAE probes (as well as the cooling tone) are derived from two phase-locked lasers (Methods section). The three tones are combined in a free-space setup and coupled with the same polarization into a single-mode fiber. By blocking each beam path we ascertain equal power for each probe, stable to within 1%. The light reflected from the oscillator is directed to a BHD setup, where it is mixed with a local oscillator (LO) generated by a third laser. As detailed in ref. 44, by carefully characterizing our lasers we have determined that classical laser noise is negligible in our system. Specifically, we operate far from the relaxation-oscillation peak of our diode laser56. Thus, our detection is quantum-limited, as in Eq. (1). In order to accurately tune the probes across the optical resonance, we temporarily switch the reflected light to a coherent response measurement setup (Methods section).

Observation of backaction evasion

Figure 3 shows BAE measurement of the mechanical oscillator, taken at a cryostat temperature of 2.0 K (\(\overline n _{{\mathrm{th}}} \sim 7.9\)) and buffer-gas pressure of 46 mbar. In this experiment, we vary the detuning δ/2π from +3 to −3 MHz. The total mechanical linewidth across the measurement is Γeff/2π = 607 ± 7 kHz and the other measurement parameters are np = 290, nc = 320, and \({\cal{C}}_{{\mathrm{cool}}} = 3.8\). When the probes are tuned away from the mechanical sidebands, δ/2π = 3 MHz, the PSD exhibits motional sideband asymmetry that can be used to self-calibrate the measurement in terms of mechanical quanta (including QBA heating; see left inset of Fig. 3c), yielding \(\bar n + \bar n_{{\mathrm{BA}}} = 6.3\) in this case42,43,44,48. When tuning the probes on the mechanical sidebands, δ/2π = 0 MHz, the total thermomechanical noise is reduced by 0.7 mechanical quanta, in perfect agreement with independently calculated \({\cal{C}} = 0.7\). Thus, more than 11% of the noise in the non-BAE case is due to QBA. This constitutes the first BAE measurement in the optical domain and the first with quantum-limited detection.

Experimental observation of backaction evasion. a, b Non-BAE and BAE measurements, respectively, as explained in the main text (see also Fig. 1c, d). c Data traces, normalized to the vacuum noise level, for non-BAE (cyan) and BAE measurements (purple) are shown with Lorentzian fits. The non-BAE sidebands exhibit motional asymmetry, used to self-calibrate the measurement in units of mechanical quanta. The sum of the non-BAE sidebands, indicated in dashed cyan, is larger than in the BAE case (purple) by 0.7 mechanical quanta. The right inset is a zoom of the indicated region. The left inset shows the inferred occupation \(\bar n\) as a function of the detuning δ, with an analytic curve based on Eq. (1) with no free parameters. In this measurement, nP = 290, nc = 320, and \({\cal{C}}_{{\mathrm{cool}}} = 3.8\)

We now turn to discuss technical limitations of BAE measurement imposed by our system. In conventional cavity-based position measurements employing homodyne detection11,12, one refers the on-resonance readout to mechanical quanta, i.e., expressing the peak of the measured PSD as \(\bar S_{II}^{{\mathrm{hom}}}(\Omega_{\mathrm{m}}) \propto \bar n_{{\mathrm{imp}}}^{{\mathrm{hom}}} + \overline n _{{\mathrm{BA}}} + (\bar n + \frac{1}{2})\), where \(\overline n _{{\mathrm{imp}}}^{{\mathrm{hom}}} = (16\eta {\cal{C}})^{ - 1}\) is the measurement imprecision due to shot noise (cf. Fig. 1d). The Heisenberg uncertainty relation requires \(4\sqrt {\overline n _{{\mathrm{imp}}}^{{\mathrm{hom}}}\overline n _{{\mathrm{BA}}}} \ge 1\). The SQL is achieved by minimizing the total added noise \(\overline n _{{\mathrm{add}}} = \overline n _{{\mathrm{imp}}}^{\hom } + \overline n _{{\mathrm{BA}}}\) subject to this constraint, yielding \(\overline n _{{\mathrm{add}}}^{{\mathrm{SQL}}} = (4\eta )^{ - 1/2}\) (\(\frac{1}{2}\) for ideal measurement). In a BAE measurement, there is no QBA component; however, any device suffers extraneous heating due to optical absorption, adding excess heating backaction \(\overline n _{{\mathrm{BA}}}^{{\mathrm{th}}} = \beta {\cal{C}}\) analogous to \(\overline n _{{\mathrm{BA}}}\). In addition, in heterodyne detection \(\overline n _{{\mathrm{imp}}} = (8\eta {\cal{C}})^{ - 1}\), due to twice the vacuum noise compared with homodyne detection (“image band”). The minimum added noise is \(\bar n_{{\mathrm{add}}}^{{\mathrm{th}}} = \sqrt {\beta {\mathrm{/}}2\eta }\). When \(\beta \, < \, \frac{1}{2}\), BAE outperforms conventional measurement of the same efficiency.

Figure 4 shows a set of measurements done at 1.6 K (\(\overline n _{{\mathrm{th}}} \simeq 6.3\)) and buffer-gas pressure of 30 mbar with variable probe power nP and constant cooling tone power nc = 420 (set by the maximum probe power). Both \(\bar n\) and \(\overline n _{{\mathrm{BA}}}\) are plotted against the independently measured cooperativity \({\cal{C}}\), with \(\overline n _{{\mathrm{BA}}}\) in excellent agreement with theory (blue solid line, slope of 1). The maximum QBA cancellation reached is \(\overline n _{{\mathrm{BA}}} = 1.4\) out of \(\bar n + \overline n _{{\mathrm{BA}}} = 9.8\) quanta, or 14% (reduction of 0.67 dB). The linear fit to \(\bar n\) yields β = 3.85. Thus, although QBA is evaded in our measurement, extraneous heating is still a limiting factor, as can be seen directly from Fig. 4. The imprecision noise is also in excellent agreement with theory and yields η = 0.04, in agreement with previous measurements of the same system44. Thus, \(4\sqrt {\overline n _{{\mathrm{imp}}}\overline n _{{\mathrm{BA}}}^{{\mathrm{th}}}} = \sqrt {2\beta {\mathrm{/}}\eta } = 13.88\). Compared with a measurement at the SQL with the same efficiency, the optimal added noise is \(\overline n _{{\mathrm{add}}}^{{\mathrm{th}}} = 2.78 \times \overline n _{{\mathrm{add}}}^{{\mathrm{SQL}}}\).

Effect of probe power on quantum backaction and optical absorption heating. The measurements were carried out at 1.6 K and 3He buffer-gas pressure of 30 mbar, with \(n_c \simeq 420\) (\({{\cal{C}}_{{\mathrm{cool}}} \simeq 5.0}\)). The occupation \(\bar n\) and the number of evaded quantum backaction phonons \(\overline n _{{\mathrm{BA}}}\) vs. independently measured \({\cal{C}}\) are plotted on the left axis. For each value of \({\cal{C}}\), a sweep similar to Fig. 3 was performed, consisting of 7 noise spectra with δ/2π = {0, ±0.5, ±3, ±4} MHz. Each sweep was self-calibrated using motional sideband asymmetry applied to the four outermost spectra (non-backaction-evading, see Fig. 3), taking the mean and SD of the four calibrations to infer data and error bars, respectively. The solid blue line plots \(\overline n _{{\mathrm{BA}}} = {\cal{C}}\). The dashed red line is a linear fit to \(\bar n\) with slope \(\beta {\cal{C}}\) where β = 3.85. The right axis shows the imprecision noise with a fit \(\overline n _{{\mathrm{imp}}} = 1{\mathrm{/}}8\eta {\cal{C}}\) yielding η = 0.04

Discussion

We have explicitly demonstrated evasion of QBA in the optical domain. Our measurements are limited by extraneous absorption heating, which currently prohibits surpassing the SQL. This highlights the challenge to overcome such effects in optical measurements. Further improvements in device design and fabrication (to be published) increased the intrinsic optical Q, reducing the intrinsic cavity losses. This diminishes the effect of heating, while at the same time increases the detection efficiency. This may allow reaching the performance of microwave experiments, while taking advantage of quantum-limited detection, which is easily accessible in the optical domain. For example, in the microwave domain, ref. 33 reported backaction evasion of 10.7 dB, but suffered from low efficiency owing to classical amplifier noise. We note that for very strong probing, extremely accurate tuning of the probes must be achieved in order to avoid the recently reported optomechanical two-tone instability57. Our measurement opens the path for creating motional squeezed states through reservoir engineering34 demonstrated so far only in the microwave domain35,36,37,38 and generation of squeezed light through mechanical dissipation58,59.

Methods

Theory

The theory of two-tone BAE measurements in optomechanics is already well established30, but we repeat the key elements here for convenience of the reader. The system is described by the Hamiltonian

where \(\hat a\) and \(\hat b\) are the annihilation operators of a cavity photon and a mechanical phonon, respectively. The cavity is driven by a coherent drive \(\alpha _{{\mathrm{in}}}(t) = (\alpha _ + e^{ - i\Omega t} + \alpha _ - e^{i\Omega t})e^{ - i\omega _{\mathrm{l}}t}\) with carrier frequency ωl = ωc + Δ and amplitude-modulated at frequency Ω = Ωm + δ, giving \(\hat H_{{\mathrm{drive}}} = i\sqrt \kappa [\alpha _{{\mathrm{in}}}(t)\hat a^\dagger - \alpha _{{\mathrm{in}}}^ \ast (t)\hat a]\).

We follow standard procedure in cavity optomechanics4. We move to the interaction picture with respect to the Hamiltonian \(\hat H_0 = \hbar \omega _{\mathrm{l}}\hat a^\dagger \hat a + \hbar \Omega \hat b^\dagger \hat b\) and linearize the operators \(\hat a \to \bar a + \delta \hat a\), \(\hat b \to \bar b + \delta \hat b\). In this rotating frame, we can write \(\hat H = \hat H_{{\mathrm{RWA}}} + \hat H_{{\mathrm{CR}}}\) with

with \(g_ \pm = g_0\bar a_ \pm\) the drive-enhanced coupling, where \(\bar a_ \pm\) is the intracavity amplitude due to each drive tone. The counter-rotating Hamiltonian

contains off-resonant terms. Their effect has been studied perturbatively30 and through an exact solution60, but they can be neglected in resolved sideband regime \(\Omega _{\mathrm{m}} \gg \kappa\), relevant for the present experiment. Including the coupling to the mechanical and optical baths, and using standard input–output theory leads to the quantum Langevin equations61

where Γeff is the dissipation rate of the mechanical oscillator and we have introduced the optical (\(\delta \hat a_{{\mathrm{in}}}\)) and mechanical (\(\delta \hat b_{{\mathrm{in}}}\)) input noise operators. We have assumed for simplicity no intrinsic optical losses (highly overcoupled cavity). In the rotating frame, the mechanical quadrature operators are given by \(\hat X = \frac{1}{{\sqrt 2 }}(e^{i\delta t}\delta \hat b^\dagger + e^{ - i\delta t}\delta \hat b)\) and \(\hat Y = \frac{i}{{\sqrt 2 }}(e^{i\delta t}\delta \hat b^\dagger - e^{ - i\delta t}\delta \hat b)\). When g+ = g− and δ = 0, the optical field couples exclusively \(\hat X\) [Eq. (5)], the key feature of BAE measurement.

By transforming the Langevin Eqs. (5) and (6) to Fourier space, we can relate the field operators in simple matrix form \({\mathbf{d}}(\omega ) = \mathbf{\chi} (\omega ){\mathbf{L}}{\kern 1pt} {\mathbf{d}}_{{\mathrm{in}}}(\omega )\) with \({\mathbf{d}} = (\delta \hat a,\delta \hat a^\dagger ,\delta \hat b,\delta \hat b^\dagger )^T\), \({\mathbf{d}}_{{\mathrm{in}}} = (\delta \hat a_{{\mathrm{in}}},{\kern 1pt} \delta \hat a_{{\mathrm{in}}}^\dagger ,\delta \hat b_{{\mathrm{in}}},{\kern 1pt} \delta \hat b_{{\mathrm{in}}}^\dagger )^T\), \({\mathbf{L}} = {\mathrm{diag}}(\sqrt \kappa ,\sqrt \kappa ,\sqrt {\Gamma _{{\mathrm{eff}}}} ,\sqrt {\Gamma _{{\mathrm{eff}}}} )\), and

with \(\chi_c(\omega)=(-i\omega+\kappa/2)^{-1}\) and \(\chi_m(\omega)=(-i\omega+\Gamma_{\mathrm{eff}}/2)^{-1}\). The output fields are given by the input–output relations, e.g., \(\delta \hat a_{{\mathrm{out}}} = \delta \hat a_{{\mathrm{in}}} - \sqrt \kappa \delta \hat a\), yielding the matrix equation \({\mathbf{d}}_{{\mathrm{out}}} = [1 - {\mathbf{L}}{\kern 1pt} {\mathbf{\chi (\omega )}}{\kern 1pt} {\mathbf{L}}]{\mathbf{d}}_{{\mathrm{in}}}\), with \({\mathbf{d}}_{{\mathrm{out}}} = (\delta \hat a_{{\mathrm{out}}},\delta \hat a_{{\mathrm{out}}}^\dagger ,\delta \hat b_{{\mathrm{out}}},\delta \hat b_{{\mathrm{out}}}^\dagger )^T\).

The output optical field is detected using BHD, mixing it with a strong LO with frequency ωl + ΔLO (in the lab frame) on a beamsplitter and subtracting the detected intensity from the two beamsplitter output arms. This yields photocurrent with symmetrized PSD62

Using the solutions for \(\delta \hat a_{{\mathrm{out}}}\), \(\delta \hat a_{{\mathrm{out}}}^\dagger\), and the correlations of the input noise operators

where \(\bar n\) denotes the mean thermal occupation of the environment seen by the oscillator, the photocurrent PSD (8) can be evaluated. Apart from a white noise floor due to shot noise (10), both PSDs \(S_{\delta \hat a_{{\mathrm{out}}}\delta \hat a_{{\mathrm{out}}}}(\omega )\) and \(S_{\delta \hat a_{{\mathrm{out}}}^\dagger \delta \hat a_{{\mathrm{out}}}^\dagger }(\omega )\) contain information near \(\omega \approx \Gamma _{{\mathrm{eff}}},\delta \ll \Delta _{{\mathrm{LO}}}\), and appear shifted by ΔLO in the photocurrect PSD (8). We refer the measured PSD to ΔLO by setting ΔLO = 0 (see Fig. 1c, d).

We now specialize to the case Δ = 0 and g+ = g−, as in our experiment. We can also approximate \(\chi _{\mathrm{c}}(\omega ) \approx \chi _{\mathrm{c}}(0)\), as for our frequencies of interest \(\omega \ll \kappa\). Including finite detection efficiency η finally yields the PSD given in the main text, normalized to the vacuum noise level,

with optomechanical cooperativity \({\cal{C}} = 4g_0^2n_{\mathrm{p}}{\mathrm{/}}\kappa \Gamma _{{\mathrm{eff}}}\) and \(n_{\mathrm{p}} = |\bar a_\pm|^2\). For δ = 0, the quadrature \(\hat X\) is given by \(\hat X(\omega) = \sqrt {\Gamma _{{\mathrm{eff}}}/2} \chi _{\mathrm{m}}(\omega )[b_{{\mathrm{in}}}^\dagger (\omega ) + b_{{\mathrm{in}}}(\omega )]\) with PSD \(\bar S_{XX}(\omega ) = (\Gamma _{{\mathrm{eff}}}/2)(2\bar n + 1)\left| {\chi _{\mathrm{m}}(\omega )} \right|^2\).

Frequency setup and phase lock

Figure 5a shows the complete picture of the various laser tones applied in the experiment. A master laser generates the red-detuned probe and, via an acousto-optic frequency shifter, the cooling tone. Two other lasers are referenced to the master laser through a phased-locked loop and are locked at a higher frequency. One laser, locked at an offset ~ Ωm, generates the LO for the BHD. The second laser, locked at an offset ~ 2Ωm, generates the blue-detuned probe.

Complete frequency setup and phase-locked loop beat note. a The frequencies of the various tones used in the experiment. The cavity has resonance frequency ωc and linewidth κ. The mechanical resonance frequency is Ωm. The probes are applied with small detuning δ from the upper and lower mechanical sidebands. An additional cooling tone is applied as shown. The local oscillator (LO), which does not enter the cavity, is detuned by ΔLO from cavity resonance. b A typical out-of-loop PLL beat note, relative to the offset frequency. The resolution bandwidth (RBW) is 6.25 kHz. The inset shows a zoom-in with RBW of 31.25 Hz

We perform the phase-lock using a PID controller with 10 MHz bandwidth to control the current of the diode lasers. A typical beat note is shown in Fig. 5b. The residual phase error63,64,65, computed from the ratio coherent to total power, is \(\langle \sigma _\varphi ^2\rangle \simeq 5 \times 10^{ - 3} \,\, {\mathrm{rad}}^2\), limited by the resolution bandwidth.

Optomechanical cooling and absorption heating

At low temperatures, intracavity photons shift the optical resonance to higher frequencies, due to a combination of thermo-optic and thermal expansion effects in silicon. Excess blue-detuned pumping can cause thermal run-off, making operation unstable when the cavity is driven with the BAE probes alone (due to the presence of the blue-detuned probe). An additional red-detuned (cooling) tone of sufficient power is required. With the sample used in this experiment, we have found empirically that we need \(n_{\mathrm{c}} \,\gtrsim \, n_{\mathrm{p}}{\mathrm{/}}2\) for stable operation, where nc denotes the intracavity photons due to the cooling tone and nP denotes the intracavity photons due to each probe.

Probe tuning via coherent response

In experiments such as this, it is of utmost importance to tune the probes accurately around the optical resonance. Active locking to the cavity (e.g., using a Pound–Drever–Hall technique) are inappropriate for a single-sided cavity and also result in driving the cavity on resonance. We use passive tuning of our master laser, from which the other tones are derived, using the cavity coherent response, similar to previous experiments66. From the response curve we extract accurate values of both Δ and κ. Here we give details on the method. A simplified setup is shown in Fig. 6a. The laser is phase-modulated using RF output of a network analyzer (NA). The carrier and sidebands reflected from the cavity interfere on a fast photodetector and the photocurrent fed to the NA input, measuring the magnitude of the S21 parameter. The amplitude incident on the cavity is given by

with β the modulation index and the reflected light is

with

the amplitude reflection coefficient at detuning Δ and \(\eta _{\mathrm{c}} \equiv \kappa _{{\mathrm{ex}}}{\mathrm{/}}\kappa\) the cavity coupling parameter. The magnitude of the S21 parameter, the Ω frequency component of the photocurrent \(\left| {a_{{\mathrm{out}}}(t)} \right|^2\), is given by (here and below we omit a constant scale factor)

Coherent response determination of detuning and linewidth. a Simplified setup for optical measurements using coherent response (part of the full experimental setup). b An example of a measurement with a fit Eq. (17), yielding cavity linewidth κ and detuning Δ. A correction due to extraneous frequency-dependent response, measured and shown in the inset, is included in the fit

Figure 6b shows a typical coherent response measurement, which deviates significantly from a Lorentzian when Δ ~ κ, as in our case. In addition, when scanning over a wide bandwidth, one has to take into account the frequency dependence of β (due to phase modulator, rf cables, detector response, etc.). A robust and reliable procedure to calibrate the frequency dependence of the entire detection chain is to take several traces at various detunings and fit all of them simultaneously to Eq. (17) with only Δ variable across traces, and with a high-order polynomial in Ω as a prefactor. This prefactor is then applied in all subsequent fits. The inset in Fig. 6b shows the frequency dependence of β given by the polynomial. We adjust probe detuning using this method before each data point acquisition. By repeatedly acquiring Δ in a single instance, we estimate our accuracy to be ±20 MHz (±0.01 κ).

Data availability

The code and data used to produce the plots within this paper are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.2563797. All other data used in this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Caves, C. M. Quantum-mechanical radiation-pressure fluctuations in an interferometer. Phys. Rev. Lett. 45, 75–79 (1980).

Clerk, A. A., Devoret, M. H., Girvin, S. M., Marquardt, F. & Schoelkopf, R. J. Introduction to quantum noise, measurement, and amplification. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 1155–1208 (2010).

Pace, A. F., Collett, M. J. & Walls, D. F. Quantum limits in interferometric detection of gravitational radiation. Phys. Rev. A 47, 3173 (1993).

Aspelmeyer, M., Kippenberg, T. J. & Marquardt, F. Cavity optomechanics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 86, 1391–1452 (2014).

Teufel, J. D., Donner, T., Castellanos-Beltran, M. A., Harlow, J. W. & Lehnert, K. W. Nanomechanical motion measured with an imprecision below that at the standard quantum limit. Nat. Nanotechnol. 4, 820–823 (2009).

Anetsberger, G. et al. Measuring nanomechanical motion with an imprecision below the standard quantum limit. Phys. Rev. A 82, 061804 (2010).

Murch, K. W., Moore, K. L., Gupta, S. & Stamper-Kurn, D. M. Observation of quantum-measurement backaction with an ultracold atomic gas. Nat. Phys. 4, 561–564 (2008).

Purdy, T. P., Peterson, R. W. & Regal, C. A. Observation of radiation pressure shot noise on a macroscopic object. Science 339, 801–804 (2013).

Teufel, J., Lecocq, F. & Simmonds, R. Overwhelming thermomechanical motion with microwave radiation pressure shot noise. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 013602 (2016).

Schreppler, S. et al. Optically measuring force near the standard quantum limit. Science 344, 1486–1489 (2014).

Wilson, D. J. et al. Measurement-based control of a mechanical oscillator at its thermal decoherence rate. Nature 524, 325–329 (2015).

Rossi, M., Mason, D., Chen, J., Tsaturyan, Y. & Schliesser, A. Measurement-based quantum control of mechanical motion. Nature 563, 53–58 (2018).

Thorne, K. S., Drever, R. W. P., Caves, C. M., Zimmermann, M. & Sandberg, V. D. Quantum nondemolition measurements of harmonic oscillators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 40, 667–671 (1978).

Braginsky, V. B., Vorontsov, Y. I. & Thorne, K. S. Quantum nondemolition measurements. Science 209, 547–557 (1980).

Caves, C. M., Thorne, K. S., Drever, R. W. P., Sandberg, V. D. & Zimmermann, M. On the measurement of a weak classical force coupled to a quantum-mechanical oscillator. I. Issues of principle. Rev. Mod. Phys. 52, 341–392 (1980).

Braginsky, V. B. & Manukin, A. B. Ponderomotive effects of electromagnetic radiation. JETP 25, 653–655 (1967).

Purdy, T. P., Yu, P.-L., Peterson, R. W., Kampel, N. S. & Regal, C. A. Strong optomechanical squeezing of light. Phys. Rev. X 3, 031012 (2013).

Safavi-Naeini, A. H. et al. Squeezed light from a silicon micromechanical resonator. Nature 500, 185–189 (2013).

Sudhir, V. et al. Appearance and disappearance of quantum correlations in mmeasurement-based feedback control of a mechanical oscillator. Phys. Rev. X 7, 011001 (2017).

Vyatchanin, S. P. & Zubova, E. A. Quantum variation measurement of a force. Phys. Lett. A 201, 269–274 (1995).

Kimble, H. J., Levin, Y., Matsko, A. B., Thorne, K. S. & Vyatchanin, S. P. Conversion of conventional gravitational-wave interferometers into quantum nondemolition interferometers by modifying their input and/or output optics. Phys. Rev. D 65, 022002 (2001).

Kampel, N. et al. Improving broadband displacement detection with quantum correlations. Phys. Rev. X 7, 021008 (2017).

Sudhir, V. et al. Quantum correlations of light from a room-temperature mechanical oscillator. Phys. Rev. X 7, 031055 (2017).

Jaekel, M. T. & Reynaud, S. Quantum limits in interferometric measurements. Europhys. Lett. 13, 301 (1990).

The LIGO Scientific Collaboration. A gravitational wave observatory operating beyond the quantum shot-noise limit. Nat. Phys. 7, 962 (2011).

Woolley, M. J. & Clerk, A. A. Two-mode back-action-evading measurements in cavity optomechanics. Phys. Rev. A 87, 063846 (2013).

Ockeloen-Korppi, C. et al. Quantum backaction evading measurement of collective mechanical modes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 140401 (2016).

Polzik, E. S. & Hammerer, K. Trajectories without quantum uncertainties. Ann. Phys. 527, A15–A20 (2015).

Møller, C. B. et al. Quantum back-action-evading measurement of motion in a negative mass reference frame. Nature 547, 191–195 (2017).

Clerk, A. A., Marquardt, F. & Jacobs, K. Back-action evasion and squeezing of a mechanical resonator using a cavity detector. New J. Phys. 10, 095010 (2008).

Buchmann, L., Schreppler, S., Kohler, J., Spethmann, N. & Stamper-Kurn, D. Complex squeezing and force measurement beyond the standard quantum limit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 030801 (2016).

Hertzberg, J. B. et al. Back-action-evading measurements of nanomechanical motion. Nat. Phys. 6, 213–217 (2010).

Suh, J. et al. Mechanically detecting and avoiding the quantum fluctuations of a microwave field. Science 344, 1262–1265 (2014).

Kronwald, A., Marquardt, F. & Clerk, A. A. Arbitrarily large steady-state bosonic squeezing via dissipation. Phys. Rev. A 88, 063833 (2013).

Lecocq, F., Clark, J., Simmonds, R., Aumentado, J. & Teufel, J. Quantum nondemolition measurement of a nonclassical state of a massive object. Phys. Rev. X 5, 041037 (2015).

Wollman, E. E. et al. Quantum squeezing of motion in a mechanical resonator. Science 349, 952–955 (2015).

Pirkkalainen, J.-M., Damskägg, E., Brandt, M., Massel, F. & Sillanpää, M. Squeezing of quantum noise of motion in a micromechanical resonator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 243601 (2015).

Lei, C. et al. Quantum nondemolition measurement of a quantum squeezed state beyond the 3 dB limit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 100801 (2016).

Woolley, M. J. & Clerk, A. A. Two-mode squeezed states in cavity optomechanics via engineering of a single reservoir. Phys. Rev. A 89, 063805 (2014).

Ockeloen-Korppi, C. F. et al. Stabilized entanglement of massive mechanical oscillators. Nature 556, 478–482 (2018).

Weinstein, A. et al. Observation and interpretation of motional sideband asymmetry in a quantum electromechanical device. Phys. Rev. X 4, 041003 (2014).

Purdy, T. P. et al. Optomechanical Raman-ratio thermometry. Phys. Rev. A 92, 031802 (2015).

Underwood, M. et al. Measurement of the motional sidebands of a nanogram-scale oscillator in the quantum regime. Phys. Rev. A 92, 061801 (2015).

Qiu, L. et al., Motional sideband asymmetry in quantum optomechanics in the presence of Kerr-type nonlinearities. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/1805.12364 (2018).

Purdy, T. P., Grutter, K. E., Srinivasan, K. & Taylor, J. M. Quantum correlations from a room-temperature optomechanical cavity. Science 356, 1265–1268 (2017).

Safavi-Naeini, A. H. et al. Observation of quantum motion of a nanomechanical resonator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 033602 (2012).

Khalili, F. Y. et al. Quantum back-action in measurements of zero-point mechanical oscillations. Phys. Rev. A 86, 033840 (2012).

Børkje, K. Heterodyne photodetection measurements on cavity optomechanical systems: Interpretation of sideband asymmetry and limits to a classical explanation. Phys. Rev. A 94, 043816 (2016).

Chan, J., Safavi-Naeini, A. H., Hill, J. T., Meenehan, S. & Painter, O. Optimized optomechanical crystal cavity with acoustic radiation shield. Appl. Phys. Lett. 101, 081115 (2012).

Schliesser, A., Rivière, R., Anetsberger, G., Arcizet, O. & Kippenberg, T. J. Resolved-sideband cooling of a micromechanical oscillator. Nat. Phys. 4, 415–419 (2008).

Meenehan, S. M. et al. Silicon optomechanical crystal resonator at millikelvin temperatures. Phys. Rev. A 90, 011803 (2014).

Meenehan, S. M. et al. Pulsed excitation dynamics of an optomechanical crystal resonator near its quantum ground state of motion. Phys. Rev. X 5, 041002 (2015).

Riedinger, R. et al. Non-classical correlations between single photons and phonons from a mechanical oscillator. Nature 530, 313–316 (2016).

Hong, S. et al. Hanbury Brown and Twiss interferometry of single phonons from an optomechanical resonator. Science 358, 203–206 (2017).

Riedinger, R. et al. Remote quantum entanglement between two micromechanical oscillators. Nature 556, 473–477 (2018).

Kippenberg, T. J., Schliesser, A. & Gorodetsky, M. L. Phase noise measurement of external cavity diode lasers and implications for optomechanical sideband cooling of GHz mechanical modes. New J. Phys. 15, 015019 (2013).

Shomroni, I. et al., Two-tone optomechanical instability in backaction-evading measurements. Preprint at http://arXiv.org/abs/1812.11022 (2018).

Kronwald, A., Marquardt, F. & Clerk, A. A. Dissipative optomechanical squeezing of light. New J. Phys. 16, 063058 (2014).

Ockeloen-Korppi, C. et al. Noiseless quantum measurement and squeezing of microwave fields utilizing mechanical vibrations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 103601 (2017).

Malz, D. & Nunnenkamp, A. Optomechanical dual-beam backaction-evading measurement beyond the rotating-wave approximation. Phys. Rev. A 94, 053820 (2016).

Gardiner, C. W. & Zoller, P., Quantum Noise, 3rd ed. (Springer, 2004).

Bowen, W. P. & Milburn, G. J., Quantum Optomechanics (CRC Press, 2016)

Zhu, M. & Hall, J. L. Stabilization of optical phase/frequency of a laser system: application to a commercial dye laser with an external stabilizer. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 10, 802–816 (1993).

Prevedelli, M., Freegarde, T. & Hänsch, T. W. Phase locking of grating-tuned diode lasers. Appl. Phys. B 60, S241–S248 (1995).

Marino, A. M. & Stroud, C. R. Phase-locked laser system for use in atomic coherence experiments. Rev. Sci. Inst. 79, 013104 (2008).

Verhagen, E., Deléglise, S., Weis, S., Schliesser, A. & Kippenberg, T. J. Quantum-coherent coupling of a mechanical oscillator to an optical cavity mode. Nature 482, 63–67 (2012).

Acknowledgements

I.S. acknowledges support by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under Marie Skołodowka-Curie IF grant agreement number 709147 (GeNoSOS). L.Q. acknowledges support by Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) under Grant Number 163387. D.M. acknowledges support by the UK Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) under Grant Number EP/M506485/1. AN acknowledges a University Research Fellowship from the Royal Society and support from the Winton Programme for the Physics of Sustainability. T.J.K. acknowledges financial support from an ERC AdG (QuREM). This work was further supported by SNSF-NCCR Quantum Science and Technology (QSIT) under Grant Number 51NF40-160591, and the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant agreement number 732894 (FET Proactive HOT). All samples were fabricated in the Center of MicroNanoTechnology (CMi) at EPFL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

I.S. and L.Q. designed the experiment and performed the measurements and data analysis. D.M. and A.N. contribtued to the theoretical framework. T.J.K. supervised the research. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Journal peer review information: Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shomroni, I., Qiu, L., Malz, D. et al. Optical backaction-evading measurement of a mechanical oscillator. Nat Commun 10, 2086 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-10024-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-10024-3

This article is cited by

-

Coherent optical control of a superconducting microwave cavity via electro-optical dynamical back-action

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Entanglement-enhanced optomechanical sensing

Nature Photonics (2023)

-

Dissipative optomechanics in high-frequency nanomechanical resonators

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Enhanced nonlinear optomechanics in a coupled-mode photonic crystal device

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Optimal squeezed cooling of a mechanical oscillator using measurement-based vector feedback

Science China Physics, Mechanics & Astronomy (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.