Abstract

Despite the significant increase in pediatric funding, an important question is whether recent changes in the burden of disease and conditions (child and adolescent mortality and nonfatal health loss) are reflected in the National Institutes of Health’s (NIH) allocation process. As it sets future priorities, NIH acknowledges “a need to scan the landscape for unmet needs and emerging challenges” so that supported “research translates into meaningful health benefits.” Our focus is to scan the pediatric budgetary landscape, report research funding for childhood adversity and adverse childhood experiences, and to illuminate gun violence, suicide, and drug abuse/overdose as prime examples of pediatric unmet needs and emerging challenges. Our findings suggest that pediatric researchers must reconceptualize gun violence as a form of childhood adversity and adverse childhood experiences, as we also need to do for other leading causes of child and adolescent mortality such as suicide and drug abuse/overdose. As it relates to the leading cause of death for children and adolescents, pediatric-related gun violence research spending remains only 0.0017% of the NIH pediatric portfolio.

Impact

-

New data on NIH spending on ACEs and childhood adversity.

-

New data to assess the relationship of spending to pediatric burden of disease.

-

New data on pediatrics-related gun violence, suicide and drug abuse/overdose spending.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) pediatric research portfolio is defined as funding relating to diseases, disorders, and other conditions in children and adolescents, including pediatric pharmacology.1 As the authors reported in a 2022 Pediatric Research special article,2 NIH pediatric funding has increased from $3.3 to $5.5 billion—a 67% increase over the last decade (FY 2011–2021). The pediatric portfolio rose from a low of 10.6% to a high of 12.9% as a percentage of the NIH overall budget during this period.2 Despite the significant increase in pediatric funding, an important question is whether recent changes in the burden of disease and conditions (child and adolescent mortality and nonfatal health loss) are reflected in the NIH allocation process. As it sets future priorities, NIH acknowledges “a need to scan the landscape for unmet needs and emerging challenges” so that supported “research translates into meaningful health benefits.”3 Our focus here is to scan the landscape, report research funding for childhood adversity (CA), and adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), and to illuminate limited funding for gun violence, suicide, and drug abuse as prime examples of unmet needs and emerging pediatric challenges.

In the last few years, pediatric researchers have found that NIH funding across childhood diseases and conditions has been unresponsive to the changing burden of disease.4,5,6 Burden of disease is the impact of a health problem as measured by prevalence, incidence, mortality, morbidity, extent of disability, financial cost, or other indicators, each of which can be measured in different ways.7 The sum of child and adolescent mortality and morbidity is referred to as the burden of disease and can be measured by a metric—Disability Adjusted Life Years (DALYs). The DALY combines years of life lost because of premature mortality and years lost because of disability. If a disease results in premature death one can calculate how many years of life are lost in each population because of that disease. In the same way, it is possible to calculate how many years are lost in terms of quality of life because of years lived with a certain disease.8

NIH funding priorities and burden of disease

The NIH affirms that the alignment of funding to disease burden is one of the many factors it considers for setting funding priorities, but it acknowledges that there is no comprehensive, standard approach for measuring burden across diseases.7 In sum, the NIH claims that there is no one-size-fits-all approach to measuring and comparing the burden across different diseases.9 The NIH reports its annual research funding in the Research, Disease, and Condition Categorization (RCDC) system.10 The RCDC displays the annual support level for various research, conditions, and disease categories according to grants, contracts, and other funding mechanisms used across the NIH, as well as disease burden data that the National Center for Health Statistics at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) publishes. However, estimates of mortality and prevalence are not available for all NIH spending categories. The RCDC spending categories are historically reported categories of conditions, or research areas (a total of 309 as of May 2022), but NIH claims that existing categories will “be refined periodically to reflect scientific advances.”11

In a cross-sectional analysis of pediatric grants in the United States, Rees et al. evaluated NIH grants that funded pediatric research in the U.S. from 2015 to 2018.4 Pediatric grants were classified according to disease categories studied.4 Rees et al. concluded that funding for pediatric research was correlated with several measures of disease burden, but some conditions were overfunded or underfunded relative to predicted funding levels based on disease burden.4 Reasoning from the different impacts of diseases and distribution of disease burden among children, Rees et al. concluded that pediatric-specific consideration of NIH funding allocation is needed.4

Responding to Rees et al.,4 Gordon and Corwin suggested that the authors neglected the “pediatric pandemic of child maltreatment” and the importance of childhood trauma and adversity in the development of mental and physical disease and behavioral morbidities (i.e., domestic violence, homelessness, criminality, mass shootings, and unemployment) across the life course.”5 This might have been a missed evidence-based opportunity for pediatric and other researchers, for the NIH reports data on child abuse and neglect funding (which declined by $10 million last fiscal year), and new federal child abuse and neglect data show an increase the first time since 2015 in the number of victims who suffered maltreatment.12

Cunningham et al. quantified federal spending on research on the leading causes of death in the U.S. for children and adolescents (ages 1–18) in 2008–2017.13 On average, $88 million per year was allocated to study motor vehicle crashes, the (prior) leading cause of death. Cancer, the third leading cause of mortality, received $335 million per year. In contrast, $12 million—only 32 grants, averaging $597 in research dollars per death—went to firearm injury prevention research among children and adolescents. Using their model, research on firearm injury prevention among children and adolescents would need to be funded at approximately $37 million per year to be on par with the level of funding allocated to the other leading causes of death when considering the pediatric mortality burden associated with each cause. The model suggests that research on firearm injury prevention is 96.7% underfunded or funded at one-thirtieth of the predicted amount—given the typical research funding response in the U.S. to disease and injury epidemics.13

Although death among children and adolescents is rare statistically, there have been increases in childhood mortality from a range of injury-related causes, including motor vehicle crashes, firearm injuries, and opioid overdoses. Cunningham et al. reported on the leading causes of death in children and adolescents in 2016: motor vehicle crashes were the leading cause of death (20% of all deaths); firearm-related injuries were the second leading cause of death (15%).14 Among firearm deaths, 59% were homicides, 35% were suicides, and 4% were unintentional injuries (i.e., accidental discharge). The intent was undetermined in 2% of firearm deaths.

Goldstick et al.15 updated the findings of Cunningham et al.13,14 on the leading causes of death among children and adolescents. The prior analysis showed that firearm-related injuries were second only to motor vehicle crashes (traffic-related and nontraffic-related) as the leading cause of death among children and adolescents. Since 2016, the gap has narrowed and, in 2020, firearm-related injuries became the leading cause of death.15 Drug overdose and poisoning increased by 83.6% from 2019 to 2020, becoming the third leading cause of death among children and adolescents. As firearm-related injury (including suicide) emerges as the leading cause of pediatric death in the U.S., gun violence (and exposure to gun-related violence) is now the greatest unmet pediatric health need and emerging challenge of our time.

The NIH portfolio: childhood adversity and adverse childhood experiences

The NIH estimates of funding for various RCDC has reported pediatrics as a category since 2008 and has subsequently added other childhood-related subcategories (i.e., pediatric cancer in 2014; childhood obesity in 2018). RCDC funding is reported for pediatric subcategories such as childhood injury (and unintentional childhood injury), child abuse and neglect, and youth violence and prevention.16 The childhood injury category includes research on injuries suffered from the fetal period to age 21, including physical child abuse and youth violence. The unintentional childhood injury category includes research on unintentional injuries, including accidents, suffered from the fetal period to age 21. All the projects in unintentional childhood injury are reported in the childhood injury category.17 Firearms research was only added as an RCDC category in 2020.

Currently, the NIH does not report funding on research related to CA or ACEs. CA is a concept that refers to a range of circumstances or events that pose a threat to a child’s physical or psychological well-being.”18 Traditional examples include child abuse and neglect, domestic violence, bullying, accidents or injuries, discrimination, extreme poverty, and community violence. Grummitt et al. defined CA as experiences involving threat (i.e., abuse, domestic violence) and deprivation (i.e., neglect, parental separation) occurring before adulthood that are likely to require significant adaptation by a child.6 Exposure to CA is a predictor of mental and physical illness across the lifespan,19,20 is associated with greater annual healthcare costs in adulthood,21,22 and has been linked to earlier all-cause mortality.23,24

Grummitt et al. examined the degree to which CA contributes to preventable causes of morbidity and mortality in the U.S.6 The results of their review suggest that CA is a leading contributor to morbidity and mortality,6 and they highlight the importance of preventing exposure to CA and intervening early (with those who have experienced CA) to prevent disease onset. A total of 19 meta-analyses (over 20 million) participants were reviewed. CA accounted for 15% of the total mortality in 2019 in the U.S., through associations with leading causes of death (including heart disease, cancer, and suicide). The greatest proportion of outcomes attributable to CA was for suicide attempts and sexually transmitted infections, for which CA accounted for up to 38% and 33%, respectively.

ACEs—a concept defined by Felitti et al.—are a subset of CAs.19 Felitti et al. grouped childhood adversities into categories: (a) physical abuse, (b) sexual abuse, (c) emotional abuse, (d) having a mother who was treated violently, (e) living with someone who was mentally ill, (f) living with someone who abused alcohol or drugs, and (g) incarceration of a member of the household.19 Most of the literature conceptualizes ACEs as stressful or traumatic events that impact the healthy development of children through adolescence and into adulthood.25 Researchers have highlighted the adverse and lasting physiological and psychosocial consequences that can result from ACE exposure.26,27,28,29 Historically, research on ACEs focused on child maltreatment, sexual abuse, parental mental illness, and family members who have been incarcerated. However, ACEs are now understood to include a broader range of adverse events, including youth experiences with bullying, the juvenile justice system, and parental absence.30,31,32,33 The CDC have expanded ACEs to include “potentially traumatic events that occur in childhood such as neglect, experiencing or witnessing violence, and having a family member attempt or die by suicide.”34

Although childhood and adolescent experiences with violence are captured in some ACE measures, Rajan et al. concluded that childhood exposure to gun violence has not been included in the operationalizing and scientific study of ACEs.35 The authors conducted a systematic review of peer-reviewed articles on (a) the assessment of and response to ACEs in the context of violence exposure; and (b) the assessment of and response to youth exposure to violence with a gun to determine whether gun violence exposure should be classified as an ACE. Rajan et al. illustrated similarities between the nature of gun violence exposure and other ACEs, the impact of gun violence exposure and ACEs on a range of health outcomes, and the need for interventions and resources to support children and adolescents who have had ACEs, and similarly for individuals who have been exposed to gun violence.35 In sum, a review of the existing literature provided reasonable evidence that supports classifying pediatric gun violence exposure as an ACE.35

Although gun violence and exposure has been understudied as a form of ACE, recent research has focused attention on this now leading cause of death in children and adolescents. Goldstick et al. reported that firearm-related injuries became the leading cause of death in the pediatric age group in 2020.15 These statistics are focused only on childhood and adolescent mortality attributable to gun violence and not on the additional childhood burden of exposure to gun violence. These updated findings require us to reconceptualize gun violence as a form of CA and ACE, as we also need to do for other leading causes of child and adolescent death such as suicide and drug abuse/overdose.

For more than two decades, no dedicated federal research funding existed for gun violence and injury prevention until 2020 when the U.S. House of Representatives included $25 million for gun violence research, split evenly between the CDC and NIH.36 The NIH has funded firearms research for only the past 2 years, investing a modest $14 and $19 million in funding in 2020 and 2021.37 One analysis, using other major diseases and history of federal funding as a guide, demonstrates that approximately $37 million per year over the next decade is needed to realize a reduction in pediatric firearm mortality that is comparable to that observed for other pediatric causes of death.13

NIH funding update: emerging challenges and unmet needs

The NIH RePORT Expenditures and Results (RePORTER) module allows researchers to search a repository of NIH-funded research projects and access publications and patents resulting from NIH funding.10,11 The authors rely on the NIH RePORT matchmaker to enter keywords and retrieve a list of similar projects from the RePORTER database. The NIH RePORT matchmaker was searched for the following keywords or concepts: “childhood adversity,” “adverse childhood experiences,” gun violence,” “suicide,” and “drug overdose.” To identify pediatric-related spending on gun violence, suicide, and drug overdose, we used a Stata (statistical software for data science) command to identify funded grants within each category (drug overdose, suicide, gun violence) whose project terms include “adolescent,” “child,” youth” or “pediatric” as well as within each category (ACE, Childhood Injury” whose project terms include “gun violence.”

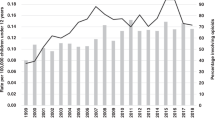

Figure 1 reports NIH research funding on CA, ACEs, and childhood injury between FY 2010 and FY 2021. Childhood injury spending increased by 220% ($101–$324 million), CA by 3739% ($2.87–$110 million), and ACEs by 1675% ($4.27–$75.75 million). However, as a percentage of the NIH pediatric budget portfolio ($5.4 billion), these funding investments remain modest: childhood injury is at 5.9% ($324 million), CA at 2% ($110 million), and ACEs at 1.4% ($75 million) in FY 2021. Table 1 reports all spending between FY 2010 and 2021.

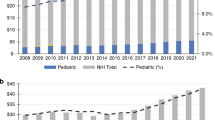

Figure 2 reports on NIH research funding on pediatric-related gun violence, suicide, and drug overdose between FY 2016 and 2021. Pediatric-related gun violence spending increased by 401% ($1.81–$9.09 million), pediatric-related suicide spending by 205% ($77.02–$235 million), and pediatric-related drug overdose spending by 563% ($12.99–$86.12 million). However, pediatric research investment remains modest compared to overall spending: pediatric-related gun violence is 45.9% of all gun violence spending, pediatric-related suicide is 43.8% of all suicide spending, and pediatric-related drug overdose is only 14.1% of all drug overdose spending. Table 2 reports all spending between FY 2010 and 2021.

Table 3 reports “suicide” funding within the ACEs portfolio and highlights “gun violence” within the childhood injury portfolio. On average, “suicide” represented only 4% of all ACE funding, and “gun violence” only represented 1% of all childhood injury funding. If a suicide attempt or suicide death of a parent or other household member is a major ACE, there is an urgent need for pediatric mental health research. Moreover, if firearm injuries and deaths adversely and directly affect children and adolescents, and if in addition to physical harm direct and indirect exposure to gun violence can negatively affect pediatric mental health and well-being, pediatric and public researchers must address the most significant unmet need and challenge of our time.

The need for increased specific NIH research funding for childhood gun violence is critical.38 From 2019 to 2020, the relative increase in the rate of firearm-related deaths (including suicide, homicide, unintentional, and undetermined) among children and adolescents was 29.5%—more than twice as high as the relative increase in the general population. The increase was observed across most demographic characteristics and types of firearm-related death.15 Indeed, exposure to gun violence is not evenly distributed. In 2021, the rate of firearm-related deaths among Black children and adolescents was 12.0 per 100,000–higher than any other racial and ethnic group and six times higher than the rate among White children. Although Black children made up 14% of the youth population in the U.S. in 2021, they accounted for 46% of firearm deaths. In addition, from 2018 to 2021, the rate of firearm-related deaths doubled among Black children and increased by 50% among Hispanic children and adolescents. Although firearm death rates for American Indian and Alaska Native children and adolescents fluctuated during the same period, they also remained higher than the rates for White children. White children and adolescents experienced stable and lower firearm mortality rates from 2018 to 2021 (from 2.0 to 2.3 per 100,000), while Asian children and adolescents had the lowest firearm mortality rates.39 As Morral and Smart noted, there is no comprehensive national resource that documents firearm-related morbidity and mortality, including the distribution among individuals and local populations from all types of diverse backgrounds.40 Therefore, research funding should also address the epidemiology of the exceptionally high rates of firearm injury and related morbidity and mortality that are unique in the U.S. among developed countries.41

Conclusion

We need more and better publicly available data. The authors advocate for the NIH to include new RCDC categories on CA and ACEs as well as pediatric subcategories on gun violence, mental health/suicide, and drug overdose/abuse. If NIH is committed to “scan the landscape for unmet needs and emerging challenges” and to refine RCDC categories “periodically to reflect scientific advances,” pediatric researchers must have access to newly available data from such efforts to conduct new research on CA and ACEs and their burden of disease. To decrease the childhood and adolescent morbidity and mortality rate, there must be a substantial increase in NIH research funding on CA and ACEs, as well as pediatric-related gun violence, mental health, and drug abuse.

Numerous articles reinforce associations among gun violence, suicide, and drug overdose/abuse in childhood as likely causes of increasing disease burden among children and adolescents, during those periods of life and throughout adulthood. It is critical, though, to move from research on associations with adverse outcomes to investments in identification, prevention, and treatment. What is needed from NIH, CDC and other federal health funding agencies is research into the mechanisms for these associations that might lead to more specific preventions and treatments.42 The recent increase NIH funding for CA, despite the limited amounts that are far less than for other adverse health conditions in children, is a step in the right direction. Research specifically addressing the basic characteristics of gun violence, gun-related injuries, deaths, and interventions remains far behind other areas of research. Such limited NIH- and CDC-funded gun violence research has hampered the development of evidence-based approaches to prevent or at least decrease firearm injuries and deaths in American children.13,43,44 As Lee et al. noted, such research should include determining risks and protective factors, intervention strategies, the impact of gun safety technology, and the influence of media.45 Better data sources for such research (e.g., a real-time data surveillance system for injuries caused by guns) are critical to more fundamentally understand the dynamics of firearm injuries and deaths.46 NIH and other federal research investments are fundamental to help resolve the unaddressed and unanswered questions about how to reduce substantially the adverse outcomes of gun violence, as well as the many other forms of CA noted in this and other reviews, that burden children for their lifetime. As it relates to the leading cause of death for children and adolescents, pediatric-related gun violence research spending remains only 0.0017% of the NIH pediatric portfolio.

Data availability

The data generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available at https://report.nih.gov/funding/categorical-spending#/; https://reporter.nih.gov/matchmaker.

References

National Institutes of Health, Division of Loan Repayment, Program Eligibility and Review Process. https://www.lrp.nih.gov/program/applicants/extramural/pediatric-research.

Gitterman, D. P., Hay, W. W., & Langford, W. S. Making the case for pediatric research: a life-cycle approach and the return on investment. Pediatr. Res. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-022-02141-5 (2022).

Wolinetz, C., & Rockey, S. Burden of disease and NIH funding priorities. National Institutes of Health, Office of Science Policy. https://osp.od.nih.gov/2015/06/18/burden-of-disease-and-nih-funding-priorities/ (2015).

Rees, C. A., Monuteaux, M. D., Herdell, V., Fleegler, E. W. & Bourgeois, F. T. Correlation between National Institutes of Health funding for pediatric research and pediatric disease burden in the US. JAMA Pediatr. 175, 1236–1243, https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapediatrics/article-abstract/2783700?utm_source=twitter&utm_medium=social_jamapeds&utm_term=5475620300&utm_campaign=amplification&linkId=131466955 (2021).

Gordon, J. B. & Corwin, D. L. National Institutes of Health funding priorities. JAMA Pediatr. 176, 323–324, https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapediatrics/article-abstract/2787155 (2022).

Grummitt, L. R. et al. Association of childhood adversity with morbidity and mortality in US adults: a systematic review. JAMA Pediatr. 175, 1269–1278 (2021).

National Institutes of Health, RePORT. Report on NIH Funding vs. Global Burden of Disease. https://report.nih.gov/report-nih-funding-vs-global-burden-disease (2017).

Murray, C. J. & Lopez, A. D. Global mortality, disability, and the contribution of risk factors: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet 349, 1436–1442 (1997).

Rockey, S. & Wolinetz, C. Burden of disease and NIH funding priorities. Under the Polyscope. https://nexus.od.nih.gov/all/2015/06/19/burden-of-disease-and-nih-funding-priorities/ (2015).

National Institutes of Health, RePORT. RCDC: Categorization Process: The Research, Condition, and Disease Categorization (RCDC) System. https://report.nih.gov/funding/categorical-spending/rcdc-process.

National Institutes of Health, RePORT. Frequently Asked Questions about the NIH Research, Condition, and Disease Categorization (RCDC) System. https://report.nih.gov/funding/categorical-spending/rcdc-faqs.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families. Child abuse, neglect data released: 29th edition of the Child Maltreatment Report. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/media/press/2020/2020/child-abuse-neglect-data-released (2020).

Cunningham, R. M. et al. Federal funding for research on the leading causes of death among children and adolescents. Health Aff. 38, 1653–1661 (2019).

Cunningham, R. M., Walton, M. A. & Carter, P. M. The major causes of death in children and adolescents in the United States. N. Engl. J. Med. 379, 2468–2475 (2018).

Goldstick, J. E., Cunningham, R. M. & Carter, P. M. Current causes of death in children and adolescents in the United States. N. Engl. J. Med. 386, 1955–1956, https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc2201761 (2022).

Gitterman, D. P., Hay, W. W., & Langford, W. S. 2022: The national institute of health and responding to new forms of childhood adversity. Children’s Health Care, Editorial. https://doi.org/10.1080/02739615.2022.2132949 (2022).

RCDC Team Email. (2022).

Bartlett, J. D., & Sacks, V. Adverse childhood experiences are different than child trauma, and it’s critical to understand why. Child Trends. https://www.childtrends.org/blog/adverse-childhood-experiences-different-than-child-trauma-critical-to-understand-why#:~:text=Common%20examples%20of%20childhood%20adversity,extreme%20poverty%2C%20and%20community%20violence (2019).

Felitti, V. J. et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am. J. Prev. Med. 14, 245–258 (1998).

Dube, S. R., Felitti, V. J., Dong, M., Giles, W. H. & Anda, R. F. The impact of adverse childhood experiences on health problems: evidence from four birth cohorts dating back to 1900. Prev. Med. 37, 268–277 (2003).

Bonomi, A. E. et al. Health care utilization and costs associated with childhood abuse. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 23, 294–299 (2008).

Fang, X., Brown, D. S., Florence, C. S. & Mercy, J. A. The economic burden of child maltreatment in the United States and implications for prevention. Child Abus. Negl. 36, 156–165 (2012).

Chen, E., Turiano, N. A., Mroczek, D. K. & Miller, G. E. Association of reports of childhood abuse and all-cause mortality rates in women. JAMA Psychiatry 73, 920–927 (2016).

Kuhlman, K. R., Robles, T. F., Bower, J. E. & Carroll, J. E. Screening for childhood adversity: the what and when of identifying individuals at risk for lifespan health disparities. J. Behav. Med. 41, 516–527 (2018).

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Adverse Childhood Experiences. https://www.samhsa.gov/capt/practicing-effective-prevention/prevention-behavioral-health/adverse-childhood-experiences (2018).

Kim, P. et al. Effects of childhood poverty and chronic stress on emotion regulatory brain function in adulthood. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 18442–18447 (2013).

Marusak, H. A., Martin, K. R., Etkin, A. & Thomason, M. E. Childhood trauma exposure disrupts the automatic regulation of emotional processing. Neuropsychopharmacol 40, 1250–1258 (2015).

Wilson, R. S. et al. Emotional neglect in childhood and cerebral infarction in older age. Neurology 79, 1534–1539 (2012).

Parnes, M. F. & Schwartz, S. E. O. Adverse childhood experiences: examining latent classes and associations with physical, psychological, and risk-related outcomes in adulthood. Child Abus. Negl. 127, 105562 (2022).

Blodgett, C. & Lanigan, J. D. The association between adverse childhood experience (ACE) and school success in elementary school children. Sch. Psychol. Quart. 33, 137–146 (2018).

Garrido, E. F., Weiler, L. M. & Taussig, H. N. Adverse childhood experiences and health-risk behaviors in vulnerable early adolescents. J. Early Adolesc. 38, 661–680 (2018).

Mersky, J. P., Janczewski, C. E. & Topitzes, J. Rethinking the measurement of adversity: moving toward second-generation research on adverse childhood experiences. Child Maltreat. 22, 58–68 (2017).

Wade, R., Shea, J. A., Rubin, D. & Wood, J. Adverse childhood experiences of low-income urban youth. Pediatrics 134, e13–e20 (2014).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Office of the Associate Director for Policy and Strategy. Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs). https://www.cdc.gov/policy/polaris/healthtopics/ace/index.html (2021).

Rajan, S., Branas, C. C., Myers, D. & Agrawal, N. Youth exposure to violence involving a gun: evidence for adverse childhood experience classification. J. Behav. Med. 42, 646–657 (2019).

Wadman, M. NIH quietly shelves gun research program: agency says it might still renew funding opportunity, which answered Obama call after school shooting. Science Insider. https://www.science.org/content/article/nih-quietly-shelves-gun-research-program (2017).

National Institutes of Health. Estimates of funding for various research, condition, and disease categories (RCDC). https://report.nih.gov/funding/categorical-spending#/ (2022).

The Johns Hopkins Center for Gun Violence Solutions, Bloomberg School of Public Health. A Year in Review: 2020 Gun Deaths in the U.S. (2022).

Panchal, N. The impact of gun violence on children and adolescents. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/other/issue-brief/the-impact-of-gun-violence-on-children-and-adolescents/ (2022).

Morral, A. R. & Smart, R. A. new era for firearm violence prevention research. JAMA 328, 1197–1198 (2022).

Kaufman, E. J. & Delgado, M. K. The epidemiology of firearm injuries in the US: the need for comprehensive, real-time, actionable data. JAMA 328, 1177–1178 (2022).

Sathya, C., Dreier, F. L. & Ranney, M. L. To prevent gun injury, build better research. Nature 610, 30–33 (2022).

Health Management Associates. Cost Estimate of Federal Funding for Gun Violence Research and Data Infrastructure. https://assets.joycefdn.org/content/uploads/CostEstimateofFederalFundingforGunViolenceResearch.pdf?mtime=20210712175851&focal=none (2021).

Alcorn, T. Trends in research publications about gun violence in the United States, 1960 to 2014. JAMA Intern. Med. 177, 124–126 (2017).

Lee, L. K. et al. Firearm-related injuries and deaths in children and youth: injury prevention and harm reduction. [Policy Statement]. Pediatrics. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2022-060070 (2022).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS): National Conference: 20 Years of Linking Data to Save Lives. (16–18 May 2023, Milwaukee, WI). https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/datasources/nvdrs/index.html.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.P.G. drafted article and oversaw analysis. W.W.H. wrote on implications for pediatric-related research. W.S.L. completed analysis and created figures and tables.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Gitterman, D.P., Hay, W.W. & Langford, W.S. The NIH childhood adversity portfolio: unmet needs, emerging challenges. Pediatr Res (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-022-02440-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-022-02440-x