Abstract

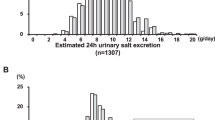

The purpose of this study was to evaluate long-term compliance with salt restriction in Japanese cardiology outpatients assessed by spot urine measurements. A total of 466 patients (72±10 years old, 216 females) who visited a cardiology outpatient clinic and were followed for at least 1 year were included in this study. Daily dietary salt intake was estimated based on the sodium and creatinine concentrations determined by spot urine at the time of enrollment, during an 8–26 week follow-up and at a long-term follow-up (>1 year). The average follow-up duration was 2.2±0.6 (1.0–3.4) years after enrollment, and spot urines were collected 5.2±2.8 times after 1 year. The baseline estimated salt excretion was 9.6±2.7 g per day, which was reduced to 8.7±2.3 g per day (P<0.01) at 8–26 weeks and remained unchanged at the long-term follow-up (8.9±2.0 g per day, P=0.36 vs. 8–26 weeks, P<0.01 vs. baseline). The percent of patients who achieved an average salt excretion<6.0 g per day was unchanged from baseline (6.9% vs. 7.7%, P=0.61). Among several variables (gender, age, body weight, salt excretion at enrollment) that might affect the incidence of salt excretion <6.0 g per day, salt excretion at baseline was the only determinant of successful salt restriction (P<0.01). In conclusion, compliance with salt restriction, assessed using a spot urine method, was maintained over the long term; however, achieving salt reduction to the level recommended by the guidelines remains a challenge.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Dietary salt restriction is recommended for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in patients with hypertension and heart failure as well as in the general population.1, 2 However, salt reduction is difficult to achieve without information regarding the daily salt intake of the patient. We have previously reported that the estimation of salt intake by a spot urine method may be a useful tool to motivate patients to reduce their salt intake within 8–26 weeks.3 However, short-term efficacy does not necessarily correlate with long-term efficacy, which contributes to the reduction in cardiovascular events. In this study, we prospectively evaluated the long-term efficacy of this spot urine-guided salt reduction approach.

Methods

This study was a prospective observational one of a previously reported cohort.3 A total of 524 patients (72±10 years, 246 females) who visited the outpatient cardiology clinic of Ueki Hospital, Kumamoto, Japan between September 2009 and November 2011 were described in a previous report. This cohort was followed until February 2013. Patients in whom salt excretion could be evaluated at least once after 1 year were included in this study. The average values of salt excretion and blood pressure obtained after 1 year were used as the long-term data if they were not otherwise specified. Unaveraged values were used for analysis at the time of enrollment and at 8–26 weeks (data collected at the first visit during this period). Blood pressure (sitting office blood pressure), body weight and laboratory tests, including urinary Na and creatinine (Cr), were taken at the time of enrollment and once at least every 6 months throughout the follow-up period. Attending physicians explained the individual data to the patients and encouraged them to reduce their salt intake by simple counseling. Dietary counseling by expert dietitians was provided to selected patients at the discretion of the attending physicians. The estimated glomerular filtration rate was calculated according to a modified version of the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study equation of the Japanese Society of Nephrology.4 Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure ⩾140 mm Hg, diastolic blood pressure ⩾90 mm Hg or treatments with antihypertensive medications. Changes in blood pressure were evaluated in patients in whom antihypertensive medications remained unchanged during follow-up. The study protocol was approved by the institutional ethics committee of the hospital and informed written consent was obtained from all patients.

Estimation of salt excretion

Daily salt excretion was estimated using the following equation:5, 6

Estimated 24 h urinary salt excretion (g per day)=1.285 × (Na (mEq l−1)/Cr (mg l−1) in spot urine × expected 24 h Cr excretion)0.392, where the expected 24 h Cr excretion (mg per day)= −2.04 × age (years old)+14.89 × weight (kg)+16.14 × height (cm)−2244.45.

Statistical analysis

The data are presented as the mean±s.d. The event frequencies were compared using the χ2-test. Differences in the variables were assessed using a one-way analysis of variance when at least three groups were being compared, followed by the Tukey–Kramer honestly significant different test. Comparisons between two groups of data were made using paired or unpaired Student’s t-tests. Logistic regression models were applied to assess the determinants of low salt excretion. A P-value <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. The statistical software package JMP (version 9, SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) was used for the analyses.

Results

Patient characteristics

After the initial enrollment of 524 patients, 58 patients, including 5 deaths and 1 disabling stroke, were lost to follow-up before 1 year. Thus, 466 (89%) patients (72±10 years old, 216 female) were included in this study. The baseline characteristics of the patients are presented in Table 1; these are similar to those previously reported.3 The average follow-up duration was 2.2±0.6 (range: 1.0–3.4) years after enrollment. Spot urines were collected 5.2±2.8 (range: 1–15) times after 1 year. Dietary counseling by expert dietitians was provided to only 33 (7.0%) patients.

Changes in daily salt excretion

Table 2 shows the changes in clinical parameters at the time of enrollment, at 8–26 weeks, and at a long-term follow-up (>1 year). Daily dietary salt excretion was reduced from 9.6±2.7 to 8.7±2.3 g per day (P<0.01) after 8–26 weeks. The average salt excretion after 1 year was not different (8.9±2.0 g per day) compared with 8–26 weeks (P=0.36) but remained significantly lower than baseline values (P<0.01). These results were almost identical when patients who were educated by the dieticians were excluded (n=433, 9.6±2.6, 8.7±2.3 and 8.9±1.9 g per day, at the time of enrollment, 8–26 weeks and after 1 year, respectively). Compared with the values at baseline and 8–26 weeks, the maximum salt excretion after 1 year was significantly (P<0.01) greater (10.9±2.7 g per day), whereas the minimum salt excretion after 1 year was significantly (P<0.01) lower (7.1±1.9 g per day). These results were similar among all gender and age, but long-term efficacy was not apparent in older (⩾75 years) males (P=0.076). For the disease-specific analysis, similar results were obtained in patients with hypertension, congestive heart failure and atrial fibrillation, but long-term efficacy was not observed in patients with diabetes mellitus (n=92, P=0.29, 87 patients had hypertension, congestive heart failure or atrial fibrillation). The percentage of patients who achieved a daily salt excretion <6.0 g per day demonstrated a trend of increase from 7.7 to 11.2% (P=0.073) at 8–26 weeks. The percentage of patients who achieved an average salt excretion <6.0 g per day decreased to 6.9% (P=0.022), showing no difference from the baseline value. The percentages of patients who achieved a salt excretion <6.0 g per day on all occasions or at least once were 3.4% and 29.6%, respectively.

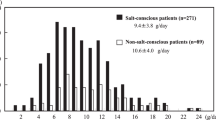

Determinants of patients who achieved salt restriction

Table 3 compares the characteristics of the patients who achieved an average salt excretion <6 g per day at the long-term follow-up to those who did not. Patients with low salt excretion were more likely to be female and older, with a lower body weight and lower salt excretion at enrollment. However, multiple logistic regression analysis (Table 4, left column) revealed that only salt excretion at enrollment was a significant determinant of long-term low salt excretion. When the cutoff value was arbitrarily defined as 7 g per day, older age was a determinant of low salt excretion. When the cutoff value was increased to 8 g per day, body weight was also a determinant of low salt excretion. However, female gender was not a determinant of low salt excretion when any of the cutoff values were used.

Effects of blood pressure on dietary salt restriction

Changes in blood pressure were assessed in 222 (48%) patients in whom antihypertensive medications were unchanged during follow-up (Table 2). Systolic blood pressure was not significantly decreased. Diastolic blood pressure decreased from 74.2±10.8 to 71.2±10.1 mm Hg (P<0.01) after 8–26 weeks, but at the long-term follow-up, it was not significantly different from baseline (P=0.084). However, when patients without optimal blood pressure control (systolic blood pressure >130 mm Hg and/or diastolic blood pressure 85 mm Hg) at the time of enrollment were selected (n=104), a reduction in both systolic and diastolic pressures by salt restriction was apparent at 8–26 weeks and remained unchanged over the long term (Table 2, bottom).

Discussion

This study demonstrated that the efficacy of using a spot urine method to encourage compliance with salt restriction was maintained long term; however, achieving salt reduction to the level recommended by the guidelines7 remained difficult in Japanese outpatients.

These trends were observed regardless of gender and age, but long-term efficacy was not apparent in older (⩾75 years) males and or patients with diabetes mellitus (Table 2), suggesting that repeated instruction to reduce salt intake is particularly needed in these populations.

Ohta et al.8 reported no relationship between the awareness of salt restriction and the actual salt intake evaluated by 24 h urine collection. Because subjective awareness of salt restriction may not necessarily reflect actual salt reduction, monitoring salt excretion appears to be very important for salt reduction. Yasutake et al.9 reported that subjects using a home self-monitoring device demonstrated reduced salt excretion from 8.44 to 8.04 g per day over 3 weeks without any specific educational program, which was consistent with our results.

The previously reported findings and those of the present study indicate that for instruction to reduce salt intake, assessing salt intake for the individual patient is essential as a first step, although it should be continued long term. Ohta et al.10 have previously conducted a similar long-term study using 24 h home urine collection. The results were similar to ours, although 45.2% of their subjects achieved a salt excretion <6.0 g per day at least once and 10.3% achieved an average salt excretion <6.0 g per day, which were higher than the rates reported in this study (29.6% and 6.9%, respectively). The reasons were not clear, although they might be partially explained by the lack of dietary counseling by expert dietitians for the majority (93%) of the patients included in this study.

We attempted to identify specific characteristics of the patients who were able to maintain a low salt intake. As shown in Table 3, female gender, older age, low body weight and salt excretion at baseline (no instruction of salt restriction) were possible determinants of successful achievement of low salt intake. However, multiple logistic regression analysis revealed that only salt excretion at enrollment was a significant determinant of long-term low salt excretion. This result may indicate that patients who habitually consume large amounts of salt at baseline find it difficult to reduce salt intake to the recommended level regardless of gender, age and body weight, thus further emphasizing the need for repeated instruction regarding salt restriction to all patients in whom salt excretion levels are very high.

Study limitations

First, the estimation of daily urinary salt excretion using a spot urine sample may be less accurate than using 24 h urine collection, as noted previously.3 Further, the second morning urine method is reported to be superior to the spot urine method for estimating daily salt intake.11 This is most likely due to the circadian rhythm of urinary salt excretion, which is characterized by lower excretion during morning compared with afternoon. Because the majority (>90%) of spot urine samples in this study were collected at the time of office visits, between 09:00 and 11:00 AM, the results of our study might be underestimated. Second, we did not collect data on lifestyle factors, such as habitual alcohol intake, smoking habits, physical activity and job status, which could potentially affect salt intake.12 Third, dietary counseling by expert dietitians was provided to a limited number of patients because only one dietitian was available at the time of enrollment. Two dieticians are now available, and the number of patients receiving dietary counseling for salt restriction is being increased. Fourth, the antihypertensive medications were changed in more than half of the patients included in this study during the follow-up periods; thus, the evaluation of the changes in blood pressure is of limited value. Finally, this was a single-center, unblinded study, and additional multicenter studies and outcome trials are needed.

Conclusions

The efficacy of using a spot urine method to encourage compliance with salt restriction was maintained over the long term; however, achieving the recommended level of salt reduction remains a challenge.

References

Appel LJ, Frohlich ED, Hall JE, Pearson TA, Sacco RL, Seals DR, Sacks FM, Smith SC Jr, Vafiadis DK, Van Horn LV . The importance of population-wide sodium reduction as a means to prevent cardiovascular disease and stroke. a call to action from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2011; 123: 1138–1143.

He FJ, MacGregor GA . A comprehensive review on salt and health and current experience of worldwide salt reduction programmes. J Hum Hypertens 2009; 23: 363–384.

Hirota S, Sadanaga T, Mitamura H, Fukuda K . Spot urine-guided salt reduction is effective in Japanese cardiology outpatients. Hypertens Res 2012; 35: 1069–1071.

Matsuo S, Imai E, Horio M, Yasuda Y, Tomita K, Nitta K, Yamagata K, Tomino Y, Yokoyama H, Hishida A, Collaborators developing the Japanese equation for estimated GFR. Revised equations for estimated GFR from serum creatinine in Japan. Am J Kidney Dis 2009; 53: 982–992.

Tanaka T, Okamura T, Miura K, Kadowaki T, Ueshima H, Nakagawa H, Hashimoto T . A simple method to estimate populational 24-h urinary sodium and potassium excretion using a casual urine specimen. J Hum Hypertens 2002; 16: 97–103.

Kawano Y, Tsuchihashi T, Matsuura H, Ando K, Fujita T, Ueshima H . Working Group for Dietary Salt Reduction of the Japanese Society of Hypertension. Report of the Working Group for Dietary Salt Reduction of the Japanese Society of Hypertension: (2) Assessment of salt intake in the management of hypertension. Hypertens Res 2007; 10: 887–893.

Ogihara T, Kikuchi K, Matsuoka H, Fujita T, Higaki J, Horiuchi M, Imai Y, Imaizumi T, Ito S, Iwao H, Kario K, Kawano Y, Kim-Mitsuyama S, Kimura G, Matsubara H, Matsuura H, Naruse M, Saito I, Shimada K, Shimamoto K, Suzuki H, Takishita S, Tanahashi N, Tsuchihashi T, Uchiyama M, Ueda S, Ueshima H, Umemura S, Ishimitsu T, Rakugi H, Japanese Society of Hypertension Committee. The Japanese society of hypertension guidelines for the management of hypertension (JSH 2009). Hypertens Res 2009; 32: 3–107.

Ohta Y, Tsuchihashi T, Ueno M, Kajioka T, Onaka U, Tominaga M, Eto K . Relationship between the awareness of salt restriction and the actual salt intake in hypertensive patients. Hypertens Res 2004; 27: 243–246.

Yasutake K, Sawano K, Yamaguchi S, Sakai H, Amadera H, Tsuchihashi T . Self-monitoring urinary salt excretion in adults: a novel education program for restricting dietary salt intake. Exp Ther Med 2011; 2: 615–618.

Ohta Y, Tsuchihashi T, Onaka U, Eto K, Tominaga M, Ueno M . Long-term compliance with salt restriction in Japanese hypertensive patients. Hypertens Res 2005; 12: 953–957.

Kawamura M, Ohmoto A, Hashimoto T, Yagami F, Owada M, Sugawara T . Second morning urine method is superior to the casual urine method for estimating daily salt intake in patients with hypertension. Hypertens Res 2012; 35: 611–616.

Ohta Y, Tsuchihashi T, Kiyohara K . Relationship between blood pressure control status and lifestyle in hypertensive outpatients. Intern Med. 2011; 50: 2107–2112.

Acknowledgements

We thank Yasuo Kansui, MD, PhD, Fukuoka Dental College and Takuya Tsuchihashi, MD, PhD, Division of Hypertension, Clinical Research Institute, National Kyushu Medical Center for reviewing our manuscript and making helpful suggestions. We also thank Shun Kohsaka, MD, Department of Cardiology, Keio University School of Medicine for providing statistical assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hirota, S., Sadanaga, T., Mitamura, H. et al. Long-term compliance with salt restriction assessed using the spot urine method in Japanese cardiology outpatients. Hypertens Res 36, 1096–1099 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2013.138

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2013.138

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Self-management of salt intake: clinical significance of urinary salt excretion estimated using a self-monitoring device

Hypertension Research (2016)

-

Estimated urinary salt excretion by a self-monitoring device is applicable to education of salt restriction

Hypertension Research (2015)

-

Relationship between salt intake as estimated by a brief self-administered diet-history questionnaire (BDHQ) and 24-h urinary salt excretion in hypertensive patients

Hypertension Research (2015)