Abstract

Despite intensive multimodal therapies, the overall survival rate of patients with ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreas is still poor. The chemo- and radioresistance mechanisms of this tumor entity remain to be determined in order to develop novel treatment strategies. In cancer, endocytosis and membrane trafficking proteins are known to be utilized and they also critically regulate essential cell functions like survival and proliferation. On the basis of these data, we evaluated the role of the endosomal proteins adaptor proteins containing pleckstrin homology domain, phosphotyrosine binding domain and a leucine zipper motif (APPL)1 and 2 for the radioresistance of pancreatic carcinoma cells. Here, we show that APPL2 expression in pancreatic cancer cells is upregulated after irradiation and that depletion of APPL proteins by small interfering RNA (siRNA) significantly reduced radiation survival in parallel to impairing DNA double strand break (DSB) repair. In addition, APPL knockdown diminished radiogenic hyperphosphorylation of ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM). Activated ATM and APPL1 were also shown to interact after irradiation, suggesting that APPL has a more direct role in the phosphorylation of ATM. Double targeting of APPL proteins and ATM caused similar radiosensitization and concomitant DSB repair perturbation to that observed after depletion of single proteins, indicating that ATM is the central modulator of APPL-mediated effects on radiosensitivity and DNA repair. These data strongly suggest that endosomal APPL proteins contribute to the DNA damage response. Whether targeting of APPL proteins is beneficial for the survival of patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma remains to be elucidated.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Although the incidence is quite low relative to other cancer types, ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreas (PDAC) is the fourth most common cause of cancer-related death worldwide.1, 2 There are several reasons hampering the cure of this disease. In addition to early symptoms being absent, resulting in late diagnosis and confining surgical removal, radio- and chemoresistance contributes to a 5-year survival rate of <5%.3 Not much is known about the molecular background of these resistance mechanisms. Our group and others have shown that growth factor receptors, integrins and integrin-associated molecules4, 5, 6, 7, 8 as well as proteins involved in endocytosis have a significant role in radiation survival of different tumor entities including PDAC.4, 9

The multifunctional adaptor proteins containing pleckstrin homology domain, phosphotyrosine binding domain and a leucine zipper motif (APPL) protein family controls the activity of membrane receptors by regulating endosomal trafficking and interacts with nuclear factors to modulate gene transcription and chromatin remodeling.10, 11 Two isoforms, that is, APPL1 and APPL2, are localized in a subset of early endosomes as well as in the cytoplasm and in the nucleus.10, 12 APPL1 participates in epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor internalization13 and in EGF-mediated promitotic signaling through its cytoplasmic-nuclear translocation after EGF stimulation.10 Prosurvival and radioresistance might be potentially conferred by APPL1 via its regulation of the activity and substrate specifity of the serine/threonine kinase AKT.5, 12, 14, 15 Specifically in the pancreas, loss of APPL1 results in insulin secretion deficiency via AKT.16 The nuclear functions of APPL1, that is, for gene transcription and chromatin remodeling, involve the β-catenin/T-cell factor17 and the Reptin/β-catenin/HDAC1/2 pathway, respectively,10 both signaling cascades, which have been shown to modulate cell death and cellular radiosensitivity.18, 19, 20, 21

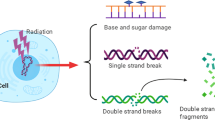

Central to radioresistance mechanisms is DNA damage repair—in particular, the repair of DNA double strand breaks (DSBs). DSBs are probably the most severe lesions of radiation-induced DNA damage.22 As a cellular response to DSBs, p53 binding protein (53BP1) is recruited to damage sites and functions as a promotor of DNA repair processes. 53BP1 has also been shown to have a role in the activation of the serine/threonine kinase ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM).23

ATM belongs to the family of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases. Following irradiation, ATM is phosphorylated at different residues including the autophosphorylation site S1981, which indicates ATM kinase activity.24 Although the molecular mechanisms are complex and far from being completely understood, several targets of ATM have been revealed. By regulating proteins like the checkpoint kinases (Chks) and p53, ATM affects the cell cycle and cell cycle arrest.25, 26 ATM is also associated with the Mre11–Rad50–NBS1 (MRN) complex as a central part of the DSB repair response.27 Interestingly, ATM has been previously shown to localize not only in the nucleus but also in the cytoplasm and in vesicles, although whether there are localization-specific functions remains unknown.28, 29

Because of the multifunctional nature of APPL proteins, we addressed whether APPL1 and APPL2 are critical for radiation survival and DSB damage response in human pancreatic cancer cells. We uncovered that APPL proteins serve as important determinants of ATM function, the DSB repair process and cellular radiosensitivity.

Results

APPL2 expression is increased after irradiation

We commenced this study by evaluating the subcellular expression and radioinducibility of APPL1 and APPL2 in the pancreatic carcinoma cell lines MiaPaCa2 and Capan-1. Both APPL1 and APPL2 proteins were localized in the cytoplasm as well as in the nucleus (Figure 1a). Moreover, we observed colocalization of about 45% of APPL2 vesicles to APPL1, whereas only 30% of APPL1 vesicles localized to APPL2 vesicles (Supplementary Figure 1). Irradiation did not change the subcellular localization of APPL1 and APPL2 but resulted in a fast and significant increase of APPL2 expression in both MiaPaCa2 and Capan-1 cell lines relative to unirradiated controls as measured by western blot (Figures 1b and c). Whereas APPL1 expression was not affected, the radiogenic APPL2 induction maintained at higher levels over the 24-h observation period. These data indicate a differential role of these proteins in both normal cell physiology and cellular radiation response.

APPL1 and APPL2 are differentially expressed upon X-ray irradiation. (a) Immunofluorescence staining of APPL1 (green) and APPL2 (red) in MiaPaCa2 and Capan-1 cells (DAPI, blue) without irradiation or after irradiation with 6 Gy. (b) Western blots and (c) densitometric analysis of APPL expression in unirradiated cells and 6-Gy-irradiated cells at indicated time points. β-Actin served as the loading control. Results show mean±S.D. (n=3; t-test; *P<0.05, **P<0.01). Statistics were calculated to compare unirradiated MiaPaCa2 (orange) or Capan-1 (red) cells with irradiated cells at indicated time points after irradiation

APPL depletion enhances the cellular sensitivity to X-rays and leads to an increased number of residual DNA DSBs

Next, we analyzed whether APPL proteins are essential in the radiation survival response by silencing APPL1 and/or APPL2 using small interfering RNA (siRNA) technology. We found that depletion of APPL proteins significantly enhanced the radiosensitivity of both MiaPaCa2 and Capan-1 cells, whereas basal cell survival was similar to siRNA controls (Figures 2a and b, Supplementary Figure 2). Supporting this, stable overexpression of APPL1 in Capan-1 cells resulted in enhanced radioresistance (Figure 2c). In addition to the pancreatic cancer cell lines, we assessed the effects of APPL1 knockdown in cancer cell lines originating from the lung, colorectum, head and neck, stomach and cervix and found no modification of their cellular radiosensitivity (Supplementary Figure 3).

APPL knockdown sensitizes pancreatic cancer cells to X-rays and impairs DSB repair. (a) Protein expression of APPL1 and APPL2 after siRNA-mediated knockdown in human MiaPaCa2 and Capan-1 cells analyzed by western blotting. β-Actin was used as the loading control. (b) Clonogenic radiation survival of APPL1 and APPL2 single or double knockdown cell cultures. Data are mean±S.D. (n=3; t-test; *P<0.05, **P<0.01). (c) Western blot from whole cell lysates and stably transfected with Cherry or Cherry-APPL1 fusion constructs. β-Actin served as the loading control. Clonogenic survival of Cherry or Cherry-APPL1 Capan-1 transfectants. Cells were irradiated 24 h after plating with 2–6 Gy or left unirradiated. Results show mean±S.D (n=3; t test; *P<0.05). (d) Representative immunofluorescence staining (53BP1, green; γH2AX, red; DAPI, blue) and quantification of foci numbers in 6-Gy-irradiated MiaPaCa2 cells after APPL1 or/and APPL2 depletion (see also Supplementary Figure 3). Data are mean±S.D. (n=3; t-test; *P<0.05, **P<0.01). Co, nonspecific siRNA control

As cellular radiation survival is strongly influenced by DNA damage repair, we next examined the number of residual DSBs dependent on APPL1 and APPL2 expression. As shown in Figure 2, APPL knockdown cultures had significantly more radiation-induced 53BP1 foci compared with controls (Figure 2d, Supplementary Figure 4). The effect of a combined downregulation of APPL1 and APPL2 on radiation survival and DNA damage was only slightly more pronounced than that caused by single knockdown of either APPL1 or APPL2 (Figures 2b and d). Interestingly, there was no effect on radiation-induced caspase-3 cleavage (Figure 3a, Supplementary Figure 5), indicating that the observed differences in cell survival are not due to increased apoptosis. Nevertheless, these data suggest that APPL1 and APPL2 are both essential regulators of the DNA damage survival and repair response and that loss of one protein cannot be fully compensated by the other.

The endosomal proteins APPL1 and APPL2 regulate the activation and phosphorylation of the DNA repair enzyme ATM. (a) Western blot and cleaved caspase-3 staining of irradiated MiaPaCa2 cells after knockdown of APPL1 and APPL2. (b) Foci analysis of pATM S1981 1 h or 24 h after irradiation with 6 Gy. Data indicate mean±S.D. (n=2). (c) Western blots and (d) densitometric analysis of indicated proteins in MiaPaCa2 cells after knockdown of APPL1 and APPL2. Whole-cell lysates from knockdown cell cultures were harvested 30 min after a 6 Gy irradiation. β-Actin served as loading control. Densitometric values of irradiated knockdown cultures were normalized to corresponding irradiated controls. Data indicate mean±S.D (n=3; t-test; *P<0.05, **P<0.01). Co, nonspecific siRNA control

APPL1 impacts radiation-induced ATM phosphorylation

The increased and similar induction of 53BP1-positive foci after irradiation resulting from APPL protein depletion (Figure 2d) is suggestive of a function of these proteins in DNA damage repair. Therefore, we evaluated the effect of APPL knockdown on ATM, a serine/threonine kinase well known to be a key regulator of DSB repair.30 After depletion of APPL1 and APPL2, the number of radiation-induced phosphorylated ATM S1981 foci—indicative of the ATM activity status24—decreased when compared with control cultures (Figure 3b). Accordingly, downregulation of APPL1 alone and in combination with APPL2, but not APPL2 alone, led to a significant reduction of ATM S1981 phosphorylation as measured by western blotting (Figures 3c and d). In contrast, proteins associated with ATM such as radiogenic phosphorylation of Chk2 and the expression of meiotic recombination 11(Mre11), Rad50 and NBS1 were not robustly affected upon APPL protein silencing (Figures 3c and d).

ATM is essential to APPL-mediated radioresistance

To evaluate whether the observed APPL1-related reduction in ATM phosphorylation upon irradiation is critically involved in APPL knockdown-mediated radiosensitization, we performed ATM siRNA transfections alone or in combination with APPL depletion. As shown in Figure 4, efficient downregulation of ATM radiosensitized the pancreatic carcinoma cells and resulted in an increase in residual 53BP1-positive foci (Figures 4a–d, Supplementary Figure 6). Additional knockdown of APPL proteins revealed no further effect on clonogenic radiation survival and radiogenic foci (Figures 4a–d), indicating that ATM, APPL1 and APPL2 are part of the same signaling axis. In addition, depletion of ATM in Capan-1 transfectants diminished the radioprotective effect of APPL1 overexpression (Figure 4e), suggesting that ATM is the key mediator of APPL1-mediated radioresistance. These findings provide evidence that APPL proteins modulate DNA repair processes by regulating ATM, thereby having an impact on cell survival after irradiation.

ATM is a major effector of radiosensitization through APPL knockdown. (a) Western blots of APPL1, APPL2 and ATM in MiaPaCa2 knockdown cell cultures. β-Actin served as the loading control. (b) Representative images and (c) corresponding clonogenic radiation survival of MiaPaCa2 cells depleted of ATM, APPL1 or APPL2 alone or in combination. Results show mean±S.D. (n=3; t-test; *P<0.05, **P<0.01). (d) DSB analysis by means of 53BP1-positive foci was performed in MiaPaCa2 upon indicated knockdown 24 h after irradiation. Data are mean±S.D. (n=3; t-test; *P<0.05, **P<0.01). (e) Western blot and radiation survival of Capan-1 Cherry- or Cherry-APPL1-expressing transfectants after ATM knockdown. Data are mean±S.D (n=3; t-test; **P<0.01). Co, nonspecific siRNA controls; n.s., not significant

APPL proteins and ATM are important modulators of DNA repair during the first hours after irradiation

To detect a differential function of APPL proteins in the early versus late phase of the DNA repair process, we next explored ATM phosphorylation and foci removal kinetics at time points ranging from 30 min to 24 h after irradiation in cells silenced for APPL1, APPL2 and ATM. In addition, we observed strongly diminished levels of phosphorylated ATM S1981 between 30 min and 2 h after 6 Gy in APPL1+2 knockdown cultures compared with controls (Figure 5a). This time interval also comprised the maximum of ATM activation, as after 24 h ATM phosphorylation was decreased to the control level (Figure 5a). In parallel, removal of 53BP1-positive foci was significantly delayed in APPL1+2, ATM and APPL1+2/ATM knockdown cultures already 2 h after irradiation (Figures 5b–d). The early time points, that is, 30 min and 2 h, indicated no significant difference in foci number of APPL1- or APPL2-depleted cells relative to controls (Figure 5d). These data show a major impact of APPL proteins on the DNA repair process conducted between 2 and 24 h, which is marginally altered by additional ATM inhibition at earlier time points than 24 h (Figures 5c and d).

APPL proteins and ATM are important modulators throughout the first 24 h of DNA repair. (a) Western blot kinetics of ATM S1981 autophosphorylation in MiaPaCa2 cells after siRNA-mediated depletion of APPL proteins and irradiation with 6 Gy. β-Actin served as loading control. (b) Western blots and (c) immunofluorescence staining of 53BP1 (green) in MiaPaCa2 knockdown cultures at indicated time points after irradiation with 2 Gy (DAPI, blue). (d) Foci analysis in 2-Gy-irradiated MiaPaCa2 cells depleted of ATM, APPL1 or/and APPL2. Statistics compare ATM, APPL1 and APPL2 single knockdown as well as APPL1+2 double knockdowns with control siRNA cultures (I–III) and ATM+APPL1, ATM+APPL2 and ATM+APPL1+2 knockdown with ATM single knockdown cultures (IV–VI). Data are mean±S.D. (n=3; t-test; *P<0.05, **P<0.01). Co, nonspecific siRNA controls; n.s., not significant

APPL1 interacts with ATM

To explore mechanistically how APPL1 modulates ATM phosphorylation, we analyzed the localization of ATM upon irradiation and additionally utilized a proximity ligation assay to detect a possible interaction between the two proteins. After irradiation, the nuclear expression of ATM and phosphorylated ATM strongly increased (Figures 6a and b). Additionally, we found a significantly enhanced interaction of phospho-ATM with APPL1 30 min after irradiation, which was mainly found in the nucleus (Figure 6c). In contrast, radiation-induced colocalization of total ATM and APPL1 occurred in the cytoplasm as well as in the nucleus (Figure 6d, Supplementary Figure 7).These data suggest that the observed APPL1/ATM interaction might be important for ATM activation and ATM-mediated DNA repair processes.

After irradiation, APPL1 interacts with ATM. Immunofluorescense staining of APPL1 and phospho-ATM (a) or ATM (b) 30 min after irradiation with 6 Gy. Unirradiated cells were used as control. Proximity ligation assay for APPL1 and phosphorylated ATM (c) or total ATM (d) in MiaPaCa2 cells. Data are mean±S.D. (n=3; t-test; **P<0.01)

Discussion

To develop strategies to overcome resistance to therapy, tumor cell biology requires further unraveling. Although DNA repair mechanisms seem to be well understood, the cellular response to genotoxic injury induced by conventional chemotherapies and radiotherapy appears to be more complex. In this study, we investigated the endosomal APPL proteins and report on their essential function in ATM-dependent DNA repair and radiation survival of human pancreatic cancer cells. Our results provide evidence that the endosomal APPL proteins regulate ATM activity and thereby influence radioresistance and DNA repair of pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells, revealing a new link between endocytic pathways and DNA repair mechanisms.

Endocytic proteins control essential cell functions like proliferation and cell survival.10, 12, 31, 32 In addition to Caveolin-1 being a key factor in caveolae-mediated endocytosis and its modulatory role in the radiation survival and DNA damage response,4, 9, 33, 34 APPL proteins also seem to be essential in this context. The first line of evidence is based on the observation that total APPL2 but not APPL1 expression is inducible by X-ray radiation, while the subcellular localization of APPL proteins remains unchanged in the pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells. Interestingly, there did not exist a 100% overlap of APPL1- and APPL2-positive vesicles either. In cervix carcinoma cells, however, both APPL proteins largely colocalized, particularly in defined structures near the plasma membrane,10 leading to the assumption that APPL-mediated endocytosis is differentially regulated in these two tumor entities.

On the basis of these findings, we hypothesize a differential role of APPL1 and APPL2 in radiation survival and DSB repair response. Both proteins significantly enhanced radiosensitivity to a similar degree in the tested pancreatic cancer cell lines when depleted using siRNA. Combined silencing of APPL1 and APPL2 conferred no further radiosensitization compared with either single knockdown. These results are in line with several studies showing a role of APPL proteins in the regulation of survival mechanisms including apoptosis.10, 12, 31 In line with cellular radiosensitization, MiaPaCa2 and Capan-1 cells showed a higher number of 53BP1-positive foci 24 h after irradiation, especially under concomitant APPL protein depletion. This observation corroborates data from others that 53BP1 foci numbers correlate with radiation survival.30, 35

Despite the fact that APPL proteins interact with a variety of promitotic and prosurvival protein kinases such as EGFR and AKT, a recently published protein sequence analysis suggested a possibility for APPL1/ATM interactions,36 which we confirm with the PLA experiments. Our experiments, based on significant downregulation of ATM S1981 autophosphorylation under APPL1 silencing, point to a possible regulatory association of both proteins. Intriguingly, the MRN complex, although undoubtedly an important factor in DNA repair processes,27, 37 was unaffected by both irradiation and APPL knockdown. One possible explanation for these observations could be the R248W mutation within the p53 protein sequence, which is present in MiaPaCa2 cells.38 Song and Hollstein39 found that this specific p53 mutation results in diminished binding of Mre11-Rad50-NBS1 to DSBs causing reduced activation of the DNA repair machinery.

Taking current knowledge into account, it was expected to see an increase in radiosensitivity and 53BP1 foci in the pancreatic carcinoma cells after ATM knockdown. Not only do data from patients with ataxia telangiectasia but also a large amount of in vitro and in vivo studies give evidence for ATM’s central function in the cellular radiation response.37, 40, 41, 42 As additional depletion of APPL proteins had equal effects as with ATM knockdown alone, we concluded that ATM and APPL proteins are part of the same signaling axis. The strongest induction of ATM phosphorylation could be observed between 30 min and 2 h after irradiation, whereas after 24 h phospho-ATM expression declined to the level of unirradiated cells. Similar findings were previously obtained in cells of other tumor entities such as lung cancer.18 A further indication for an interrelation between APPL proteins and ATM was given by the analysis of the DNA repair kinetics. Single depletion of APPL1, APPL2 and ATM modulated early and late DSB repair phases and displayed analogous time kinetics of foci removal, and this was even more pronounced upon the combined knockdown of APPL1/ATM and APPL2/ATM.

In summary, our study shows a critical function of the endosomal APPL proteins on radiation survival and DNA repair mechanisms of pancreatic carcinoma cells. The presented data indicate a regulatory interaction of APPL proteins with the DNA repair kinase ATM, thus providing novel insights into molecular processes controlling cell fate and tumor cell resistance.

Materials and Methods

Antibodies and reagents

Antibodies against APPL1 (western blot), ATM S1981 (immunofluorescence, western blot), ATM (western blot), Chk2, Chk2 Th68, Mre11, NBS1/p95, Rad50, cleaved caspase-3 (Cell Signaling, Frankfurt, Germany), 53BP1 (Novus Biologicals, Herford, Germany), ATM (immunofluorescence) (GeneTex, Irvine, CA, USA), APPL2, β-Actin (Sigma, Taufkirchen, Germany), ATM S1981 (PLA) (Rockland, Gilbertsville, PA, USA), APPL1 (immunofluorescence) (Zerial lab) and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit and sheep anti-mouse (Amersham, Freiburg, Germany), AlexaFluor 594 anti-mouse and AlexaFluor 488 anti-rabbit (Invitrogen, Darmstadt, Germany) antibodies were purchased as indicated. Complete protease inhibitor cocktail was from Roche (Mannheim, Germany), SuperSignal West Dura Extended Duration Substrate was from Thermo Scientific (Bonn, Germany), nitrocellulose membranes were from Schleicher and Schuell (Dassel, Germany), Vectashield/DAPI mounting medium from Alexis (Gruenberg, Germany), oligofectamine from Invitrogen (Karlsruhe, Germany), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) from AppliChem (Darmstadt, Germany) BSA from Serva (Heidelberg, Germany).

Cell culture and radiation exposure

Pancreatic carcinoma cell line MiaPaCa2 was purchased from DMSZ (Braunschweig, Germany). The pancreatic cancer cell line Capan-1 was kindly provided by C. Pilarsky (Department of Surgery, University Hospital, Dresden, Germany). Cells were cultured in DMEM GlutaMAX 1 medium (Gibco, Karlsruhe, Germany) supplemented with 10% (MiaPaCa2) or 20% (Capan-1) FCS (PAA, Cölbe, Germany) and 1% nonessential amino acids (PAA) at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 7% CO2. In all experiments, asynchronously growing cell cultures were used. Irradiation was delivered at room temperature using single doses of 200 kV X-rays (Yxlon Y.TU 320; Yxlon, Copenhagen, Denmark) filtered with 0.5 mm Cu. The absorbed dose was measured using a Duplex dosimeter (PTW, Freiburg, Germany). The dose rate was ∼1.3 Gy/min at 20 mA and applied doses ranged from 0 to 6 Gy.

siRNA transfection

APPL1 siRNA (sequence: 5′-GGGUGGAAAUUUAAUGAGUtt-3′), APPL2 siRNA (sequence: 5′-GGAUCUCACAGAAGUAAGCtt-3′), ATM siRNA (sequence: 5′-GGCACAAAAUGUGAAAUUCtt-3′) and the nonspecific control siRNA (sequence: 5′-GCAGCUAUAUGAAUGUUGUtt-3′) were obtained from MWG (Ebersberg, Germany). Cells were transfected as recently published43 using oligofectamine and 20 nM siRNA under serum-free cell culture conditions. At 48 h after transfection, cells were irradiated as indicated. Colony formation assay, western blotting or immunofluorescence staining was performed.

Stable transfection

Capan-1 cells were stably transfected with pCherry empty vector control or pCherry-APPL1 using Lipofectamine 2000 as previously published.6 Selection of stable transfectants was performed with G418 (Calbiochem, Darmstadt, Germany) for 6 weeks. Expression of Cherry-APPL1 or Cherry was confirmed by western blotting or fluorescence microscopy.

Colony formation assay

This assay was applied for measurement of clonogenic cell survival as published.5 Cells were plated 24 h after siRNA transfection. After another 24 h, that is, 48 h after siRNA transfection, the time of maximum silencing of protein expression, cells were irradiated with 2–6 Gy or left unirradiated. Cell colonies were stained with Coomassie blue and colonies of >50 cells were counted 9 days (Capan-1, MiaPaCa2) after plating. Plating efficiencies were calculated as follows: numbers of colonies formed/numbers of cells plated. Surviving fractions (SF) were calculated as follows: numbers of colonies formed/(numbers of cells plated (irradiated) × plating efficiency (unirradiated)). Each point on survival curves represents the mean surviving fraction from at least three independent experiments.

Total protein extractions and western blotting

Adherent cells were rinsed with ice-cold 1XPBS before harvesting total proteins by scraping using modified RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 1% Nonidet-P40, 0.25% sodium deoxycholate, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, Complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Mannheim, Germany), 1 mM Na3VO4, 2 mM NaF). Samples were stored at −80 °C. Amounts of total protein extracts were determined using BCA assay (Pierce, Bonn, Germany). After SDS-PAGE and transfer of proteins onto nitrocellulose membranes (Schleicher and Schuell), probing and detection of specific proteins was accomplished with indicated antibodies and SuperSignal West Dura Extended Duration Substrate as published.43

Immunofluorescence staining

A total number of 5 × 103 cells were plated. After 24 h, cells were irradiated with 6 Gy and fixed, by using 3% formaldehyde/PBS, 15 min or 1 h after X-ray irradiation. For control, unirradiated cells were used. Permeabilization was carried out with 0.25% Triton X-100/PBS. Immunostaining was performed using anti-APPL1 or -APPL2 antibodies and secondary Alexa Fluor594 anti-mouse or Alexa Fluor488 anti-rabbit antibodies. Fluorescence images were obtained using a laser scanning microscope (LSM) equipped with Axiovert 200 M, LSM 510 Meta from Carl Zeiss (Jena, Germany). To provide further mechanistic insight into the enhanced radiosensitivity after APPL1/APPL2/APPL1+2 and ATM silencing, we measured DNA DSBs by using the foci assay. For detection of DSBs, p53 binding protein 1 (53BP1) foci assay was performed as described.44 53BP1-positive nuclear foci of at least 150 cells were counted microscopically with an Axiscope 2 plus fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss) and defined as marker for residual DSBs.

Colocalization image analysis

Fluorescence images were taken using a Zeiss Duoscan Laser Scanning Microscope (63X oil, 1.4, 1 Airy unit). These images were then processed using MotionTracking.45 Briefly, this first involved vesicle identification and then statistical analysis.46 For colocalization, the threshold was set at 0.35 using the volume of the vesicles, and for each condition >15 000 vesicles were analyzed per experiment. Second, to determine the intensity of APPL1 in the ATM channel, the cells were first masked to show only the nuclei using the DAPI channel as a reference. Following this, the median intensity of APPL1 was found only within the ATM intensity and vice versa. This was also performed to measure the amount of APPL1 in the cytoplasm in ATM by using a mask for the inverse nucleus (i.e. masking the nuclei) and again measuring ATM in the APPL1 channel. In each experiment, the median intensity was normalized to the value at 0 Gy.

Analysis of cleaved caspase-3 and pATM S1981 foci

After siRNA-mediated knockdown and irradiation, cells were fixed in 4% PFA, permeabilized with Triton X-100, blocked in 10% fFCS and then incubated with the cleaved caspase-3 or pATM S1981 antibody in 5% FCS. DAPI was included during the secondary antibody incubation. Fluorescence images were taken using the Zeiss Duoscan Laser Scanning Microscope (63X oil, 1.4, 1 Airy unit). Visual inspection and number of cells positive for pATM foci were manually counted for the 0 Gy condition at both time point 0 and time point 24 due to the low number. At the 24 h-6 Gy condition, the nuclei were outlined in ImageJ using the DAPI channel, and the number of foci/nuclei was manually determined in the pATM channel. At the 1 h-6 Gy condition, nuclei were also outlined in ImageJ using the DAPI channel. Then using the 3D Objects Counter,47 foci/‘objects’ were identified in each image by using the same threshold conditions and size settings (10–100 voxel). The number of foci/nuclei was then counted. Incomplete nuclei were not analyzed. Approximately 100 cells per condition were examined.

Proximity ligation assay

To analyze APPL1/ATM interactions, we performed a Proximity ligation assay using the Duolink Detection Kit (Olink Bioscience, Uppsala, Sweden) according to the manufacturer’s protocol and as previously described.6 Cells were plated 24 h before irradiation with 6 Gy. Unirradiated cells were used as control. After 30 min, cells were fixed, permeabilized and stained with primary antibodies for APPL1 and ATM. After incubation with PLA probes, ligation and amplification steps, samples were analyzed with an LSM 510 meta (Carl Zeiss). Interactions of at least 34 cells per experiment were counted.

Data analysis

Mean±S.D. of at least three independent experiments was calculated with reference to untreated controls defined in a 1.0 scale. To test statistical significance, Student’s t-test was performed using Microsoft Excel 2003 (Redmond, WA, USA). Results were considered statistically significant if a P-value of <0.05 was reached. Densitometry of western blots was performed by scanning of the exposed film and using ImageJ analysis software (www.nih.gov).

Abbreviations

- 53BP1:

-

p53 binding protein

- APPL:

-

adaptor proteins containing pleckstrin homology domain, phosphotyrosine binding domain and a leucine zipper motif

- ATM:

-

ataxia telangiectasia mutated

- Chk:

-

checkpoint kinase

- DSB:

-

double strand break

- EGF:

-

epidermal growth factor

- HDAC:

-

histone deacetylase

- LSM:

-

laser scanning microscope

- Mre11:

-

Meiotic recombination 11

- MRN:

-

Mre11–Rad50–NBS1 complex

- NBS1:

-

Nijmegen breakage syndrome protein 1

- PDAC:

-

ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreas

References

Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A . Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 2012; 62: 10–29.

Hariharan D, Saied A, Kocher HM . Analysis of mortality rates for pancreatic cancer across the world. HPB (Oxford) 2008; 10: 58–62.

Penchev VR, Rasheed ZA, Maitra A, Matsui W . Heterogeneity and targeting of pancreatic cancer stem cells. Clin Cancer Res 2012; 18: 4277–4284.

Hehlgans S, Eke I, Storch K, Haase M, Baretton GB, Cordes N . Caveolin-1 mediated radioresistance of 3D grown pancreatic cancer cells. Radiother Oncol 2009; 92: 362–370.

Eke I, Koch U, Hehlgans S, Sandfort V, Stanchi F, Zips D et al. PINCH1 regulates Akt1 activation and enhances radioresistance by inhibiting PP1alpha. J Clin Invest 2010; 120: 2516–2527.

Eke I, Deuse Y, Hehlgans S, Gurtner K, Krause M, Baumann M et al. beta(1)Integrin/FAK/cortactin signaling is essential for human head and neck cancer resistance to radiotherapy. J Clin Invest 2012; 122: 1529–1540.

Morgan MA, Parsels LA, Kollar LE, Normolle DP, Maybaum J, Lawrence TS . The combination of epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors with gemcitabine and radiation in pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2008; 14: 5142–5149.

Eke I, Storch K, Krause M, Cordes N . Cetuximab attenuates its cytotoxic and radiosensitizing potential by inducing fibronectin biosynthesis. Cancer Res 2013; 73: 5869–5879.

Cordes N, Frick S, Brunner TB, Pilarsky C, Grutzmann R, Sipos B et al. Human pancreatic tumor cells are sensitized to ionizing radiation by knockdown of caveolin-1. Oncogene 2007; 26: 6851–6862.

Miaczynska M, Christoforidis S, Giner A, Shevchenko A, Uttenweiler-Joseph S, Habermann B et al. APPL proteins link Rab5 to nuclear signal transduction via an endosomal compartment. Cell 2004; 116: 445–456.

Hupalowska A, Pyrzynska B, Miaczynska M . APPL1 regulates basal NF-kappaB activity by stabilizing NIK. J Cell Sci 2012; 125: 4090–4102.

Schenck A, Goto-Silva L, Collinet C, Rhinn M, Giner A, Habermann B et al. The endosomal protein Appl1 mediates Akt substrate specificity and cell survival in vertebrate development. Cell 2008; 133: 486–497.

Lee JR, Hahn HS, Kim YH, Nguyen HH, Yang JM, Kang JS et al. Adaptor protein containing PH domain, PTB domain and leucine zipper (APPL1) regulates the protein level of EGFR by modulating its trafficking. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2011; 415: 206–211.

Mitsuuchi Y, Johnson SW, Sonoda G, Tanno S, Golemis EA, Testa JR . Identification of a chromosome 3p14.3-21.1 gene, APPL, encoding an adaptor molecule that interacts with the oncoprotein-serine/threonine kinase AKT2. Oncogene 1999; 18: 4891–4898.

Deng R, Tang J, Ma JG, Chen SP, Xia LP, Zhou WJ et al. PKB/Akt promotes DSB repair in cancer cells through upregulating Mre11 expression following ionizing radiation. Oncogene 2010; 30: 944–955.

Cheng KK, Lam KS, Wu D, Wang Y, Sweeney G, Hoo RL et al. APPL1 potentiates insulin secretion in pancreatic beta cells by enhancing protein kinase Akt-dependent expression of SNARE proteins in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2012; 109: 8919–8924.

Rashid S, Pilecka I, Torun A, Olchowik M, Bielinska B, Miaczynska M . Endosomal adaptor proteins APPL1 and APPL2 are novel activators of beta-catenin/TCF-mediated transcription. J Biol Chem 2009; 284: 18115–18128.

Storch K, Eke I, Borgmann K, Krause M, Richter C, Becker K et al. Three-dimensional cell growth confers radioresistance by chromatin density modification. Cancer Res 2010; 70: 3925–3934.

Watson RL, Spalding AC, Zielske SP, Morgan M, Kim AC, Bommer GT et al. GSK3beta and beta-catenin modulate radiation cytotoxicity in pancreatic cancer. Neoplasia 2010; 12: 357–365.

Bolden JE, Shi W, Jankowski K, Kan CY, Cluse L, Martin BP et al. HDAC inhibitors induce tumor-cell-selective pro-apoptotic transcriptional responses. Cell Death Dis 2013; 4: e519.

Abu-Baker A, Laganiere J, Gaudet R, Rochefort D, Brais B, Neri C et al. Lithium chloride attenuates cell death in oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy by perturbing Wnt/beta-catenin pathway. Cell Death Dis 2013; 4: e821.

Khanna KK, Jackson SP . DNA double-strand breaks: signaling, repair and the cancer connection. Nat Genet 2001; 27: 247–254.

Noon AT, Goodarzi AA . 53BP1-mediated DNA double strand break repair: insert bad pun here. DNA Repair (Amst) 2011; 10: 1071–1076.

Bakkenist CJ, Kastan MB . DNA damage activates ATM through intermolecular autophosphorylation and dimer dissociation. Nature 2003; 421: 499–506.

Chaturvedi P, Eng WK, Zhu Y, Mattern MR, Mishra R, Hurle MR et al. Mammalian Chk2 is a downstream effector of the ATM-dependent DNA damage checkpoint pathway. Oncogene 1999; 18: 4047–4054.

Sinha S, Ghildiyal R, Mehta VS, Sen E . ATM-NFkappaB axis-driven TIGAR regulates sensitivity of glioma cells to radiomimetics in the presence of TNFalpha. Cell Death Dis 2013; 4: e615.

Williams RS, Williams JS, Tainer JA . Mre11-Rad50-Nbs1 is a keystone complex connecting DNA repair machinery, double-strand break signaling, and the chromatin template. Biochem Cell Biol 2007; 85: 509–520.

Watters D, Khanna KK, Beamish H, Birrell G, Spring K, Kedar P et al. Cellular localisation of the ataxia-telangiectasia (ATM) gene product and discrimination between mutated and normal forms. Oncogene 1997; 14: 1911–1921.

Lim DS, Kirsch DG, Canman CE, Ahn JH, Ziv Y, Newman LS et al. ATM binds to beta-adaptin in cytoplasmic vesicles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1998; 95: 10146–10151.

Burma S, Chen BP, Murphy M, Kurimasa A, Chen DJ . ATM phosphorylates histone H2AX in response to DNA double-strand breaks. J Biol Chem 2001; 276: 42462–42467.

Pyrzynska B, Banach-Orlowska M, Teperek-Tkacz M, Miekus K, Drabik G, Majka M et al. Multifunctional protein APPL2 contributes to survival of human glioma cells. Mol Oncol 2013; 7: 67–84.

Meyer C, Liu Y, Kaul A, Peipe I, Dooley S . Caveolin-1 abrogates TGF-beta mediated hepatocyte apoptosis. Cell Death Dis 2013; 4: e466.

Zhang Y, Yu S, Zhuang L, Zheng Z, Chao T, Fu Q . Caveolin-1 is involved in radiation-induced ERBB2 nuclear transport in breast cancer cells. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technolog Med Sci 2012; 32: 888–892.

Dittmann K, Mayer C, Kehlbach R, Rodemann HP . Radiation-induced caveolin-1 associated EGFR internalization is linked with nuclear EGFR transport and activation of DNA-PK. Mol Cancer 2008; 7: 69.

Pilch DR, Sedelnikova OA, Redon C, Celeste A, Nussenzweig A, Bonner WM . Characteristics of gamma-H2AX foci at DNA double-strand breaks sites. Biochem Cell Biol 2003; 81: 123–129.

Matsuoka S, Ballif BA, Smogorzewska A, McDonald ER 3rd, Hurov KE, Luo J et al. ATM and ATR substrate analysis reveals extensive protein networks responsive to DNA damage. Science 2007; 316: 1160–1166.

Jeggo PA, Lobrich M . DNA double-strand breaks: their cellular and clinical impact? Oncogene 2007; 26: 7717–7719.

Berrozpe G, Schaeffer J, Peinado MA, Real FX, Perucho M . Comparative analysis of mutations in the p53 and K-ras genes in pancreatic cancer. Int J Cancer 1994; 58: 185–191.

Song H, Hollstein M, Xu Y . p53 gain-of-function cancer mutants induce genetic instability by inactivating ATM. Nat Cell Biol 2007; 9: 573–580.

Mavrou A, Tsangaris GT, Roma E, Kolialexi A . The ATM gene and ataxia telangiectasia. Anticancer Res 2008; 28: 401–405.

Ziv Y, Bar-Shira A, Pecker I, Russell P, Jorgensen TJ, Tsarfati I et al. Recombinant ATM protein complements the cellular A-T phenotype. Oncogene 1997; 15: 159–167.

Lundholm L, Haag P, Zong D, Juntti T, Mork B, Lewensohn R et al. Resistance to DNA-damaging treatment in non-small cell lung cancer tumor-initiating cells involves reduced DNA-PK/ATM activation and diminished cell cycle arrest. Cell Death Dis 2013; 4: e478.

Eke I, Schneider L, Forster C, Zips D, Kunz-Schughart LA, Cordes N . EGFR/JIP-4/JNK2 Signaling Attenuates Cetuximab-Mediated Radiosensitization of Squamous Cell Carcinoma Cells. Cancer Res 2013; 73: 297–306.

Eke I, Leonhardt F, Storch K, Hehlgans S, Cordes N . The small molecule inhibitor QLT0267 Radiosensitizes squamous cell carcinoma cells of the head and neck. PLoS One 2009; 4: e6434.

Rink J, Ghigo E, Kalaidzidis Y, Zerial M . Rab conversion as a mechanism of progression from early to late endosomes. Cell 2005; 122: 735–749.

Collinet C, Stoter M, Bradshaw CR, Samusik N, Rink JC, Kenski D et al. Systems survey of endocytosis by multiparametric image analysis. Nature 2010; 464: 243–249.

Bolte S, Cordelières FP . A guided tour into subcellular colocalization analysis in light microscopy. J Microsc 2006; 224: 213–232.

Acknowledgements

This work is partially funded by the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung 03ZIK041 (to NC) and the EFRE Europäische Fonds für regionale Entwicklung, Europa fördert Sachsen (100066308). We thank C. Pilarsky (Department of Surgery, University Hospital, Dresden) for providing Capan-1 pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells and A Giner, C Förster and I Lange for excellent technical assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Edited by A Stephanou

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on Cell Death and Disease website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Cell Death and Disease is an open-access journal published by Nature Publishing Group. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Hennig, J., McShane, M., Cordes, N. et al. APPL proteins modulate DNA repair and radiation survival of pancreatic carcinoma cells by regulating ATM. Cell Death Dis 5, e1199 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/cddis.2014.167

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/cddis.2014.167

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

APPL2 Negatively Regulates Olfactory Functions by Switching Fate Commitments of Neural Stem Cells in Adult Olfactory Bulb via Interaction with Notch1 Signaling

Neuroscience Bulletin (2020)

-

Adaptor Protein APPL2 Affects Adult Antidepressant Behaviors and Hippocampal Neurogenesis via Regulating the Sensitivity of Glucocorticoid Receptor

Molecular Neurobiology (2018)

-

ATM-deficiency increases genomic instability and metastatic potential in a mouse model of pancreatic cancer

Scientific Reports (2017)

-

Sodium glycididazole enhances the radiosensitivity of laryngeal cancer cells through downregulation of ATM signaling pathway

Tumor Biology (2016)