Abstract

Background:

HPV DNA-based screening is more effective than a Pap test in preventing cervical cancer, but the test is less specific. New HPV tests have been proposed for primary screening. The HPV mRNA test showed a similar or slightly lower sensitivity than the HPV DNA tests but with a higher specificity. We report the results of an organised HPV mRNA-based screening pilot program in Venice, Italy.

Methods:

From October 2011 to May 2014, women aged 25–64 years were invited to undergo a HPV mRNA test (Aptima). Those testing positive underwent cytological triage. Women with positive cytology were referred to colposcopy, whereas those with negative cytology were referred to repeat the HPV mRNA test 1 year later. The results of the HPV mRNA test program were compared with both the local historical cytology-based program and with four neighbouring DNA HPV-based pilot projects.

Results:

Overall, 23 211 women underwent a HPV mRNA test. The age-standardised positivity rate was 7.0%, higher than in HPV DNA programs (6.8%; relative rate (RR) 1.11, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.05–1.17). The total colposcopy referral was 5.1%, double than with cytology (2.6%; RR 2.02, 95% CI 1.82–2.25) but similar to the HPV DNA programs (4.8%; RR 1.02; 95% CI 0.96–1.08). The cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2+ detection rate with HPV mRNA was greater than in the HPV DNA programs at baseline (RR 1.50; 95% CI 1.19–1.88) and not significantly lower at the 1-year repeat (RR 0.70; 95% CI 0.40–1.16). The overall RR was 1.29 (95% CI 1.05–1.59), which was much higher than with cytology (detection rate 5.5‰ vs 2.1‰; RR 2.50, 95% CI 1.76–3.62).

Conclusions:

A screening programme based on the HPV mRNA obtained results similar to those observed with the HPV DNA test. In routine screening programmes, even a limited increase in HPV prevalence may conceal the advantage represented by the higher specificity of HPV mRNA.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

There is extensive evidence that the tests used in researching the high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) types perform better than cytology in terms of sensitivity, and reduced incidence and mortality (Sankaranarayanan et al, 2009; Arbyn et al, 2012; Ronco et al, 2014).

HPV DNA tests showed a low specificity for CIN2+ lesions. Therefore, the adoption of triage strategies for women who tested HPV-positive has been recommended (Health Council of the Netherlands, 2011; Ronco et al, 2012; von Karsa et al, 2015; Arbyn et al, 2015a).

The performance of many new tests is being evaluated (Arbyn et al, 2015b), including tests based on targets other than virus DNA. Most of these tests target the expression of the E6 and E7 oncoproteins. The rationale of these tests is to identify only those infections that are relevant to oncogenesis and not target infections that do not express oncogenic proteins. For this reason, they are expected to be more specific, while ideally not missing any or very few of the relevant lesions.

However, since such markers consider events that might be subsequent in time to infection reflected by HPV DNA detectability, the screening interval defined by the available knowledge on the low-risk period after a negative HPV DNA test cannot be automatically applied to non- HPV DNA tests (Mejier et al, 2009; Arbyn et al, 2015b).

The Aptima HPV mRNA test detects the expression of the two oncoproteins of the 12 HPV types classified as oncogenic for humans by the IARC (IARC, 2005).

Different studies have shown that the Aptima HPV mRNA test has a similar or slightly lower sensitivity than the HPV DNA tests, with a higher specificity, as a test in both a referral population and a screening population (Monsonego et al, 2011; Monsonego et al, 2012; Cuzick et al, 2013; Nieves et al, 2013; Heideman et al, 2013; Reid et al, 2015; Iftner et al, 2015).

The first evidence of longitudinal protection after a negative HPV mRNA test has recently been published and has shown that, for up to 3 years after a negative HPV mRNA test, the risk of CIN3+ was low (<0.3%) and similar to that observed after a negative HC2 test (Reid et al, 2015). However, the need for longitudinal data over longer periods and with larger samples has been affirmed (Arbyn et al, 2015b).

Evidence is lacking regarding the performance of HPV mRNA testing in the routine setting of organised, population-based cervical screening programmes, outside of the ‘ideal’ research context.

In this paper, we report the results of implementing a HPV mRNA test in an organised screening programme, in comparison with the HPV DNA pilot programs carried out in screening programmes in the neighbouring areas.

Materials and methods

Setting

The Venice Local Health Authority (LHA) is situated in northeastern Italy in the Veneto Region, (298 481 inhabitants in 2011) includes the city of Venice and suburbs. Organised cervical screening programmes were conducted throughout the Veneto Region LHAs between1997 and 2002, inviting all women between 25–64 years of age for a Pap test every 3 years, according to the European guideline recommendations (Coleman et al, 1993; Arbyn et al, 2010).

The Venice LHA program began in 1999. Since then, the target population (82 127 women in 2011) has been invited to undergo a liquid-based cytology (ThinPrep system, Hologic, Marlborough, MA, USA) every 3 years.

In 2010 the Veneto region initiated some pilot projects to examine the feasibility and performance of the HPV DNA test for use in primary screening using the results from the New Technology for Cervical Cancer (NTCC) study. The NTCC study was an Italian multicentre trial that compared the performance of the HPV DNA test vs the Pap test as a cervical cancer screening test (Ronco et al, 2010). In October 2011, the Venice cervical screening program introduced a HPV mRNA-based protocol. The Aptima HPV Assay, a test to detect HR-HPV E6/E7 mRNA (Hologic), replaced cytology as the primary test for the entire target population (women aged 25–64 years).

An ad hoc database was constructed and for each patient data relevant to invitations, appointments, responses, management and histological results was uploaded.

All the tests and treatments were free of charge. The principle results of the programme are available for consultation in the reports of the regional screening programme (Zorzi et al, 2013a).

The study had a pre-post design with geographical controls. The results of the Venice screening program with the HPV mRNA test (October 2011–May 2014) have been compared with those obtained with the DNA HPV in the four pilot projects (2010–2013) that had completed the first round by the end of the study. The HPV mRNA was also compared with the Pap test results obtained in Venice in the period immediately before (2009–2011).

In order to assess differences in background risk of women living in Venice and the other geographical areas covered by the other pilot project, referral and detection rates (DR) of Pap test-based screening programs in the two areas before HPV implementation are compared.

Screening protocols

HPV-based screening

The screening algorithm for all the pilot studies in the Veneto Region, including Venice, is in line with the guidelines of the Italian Association of Cervical Screening Programs (GISCi) (Gruppo Italiano Screening Citologico (GISCi), 2010) and the Health Technology Assessment Report’s recommendations (Ronco et al, 2012), as regards HPV DNA-based primary screening.

Three years after the previous screening episode, eligible women received a letter of invitation to participate in the new round of screening. The invitation letter included a leaflet with information about HPV. In Venice, the invitation included additional information about the experimental HPV mRNA test.

The Venice screening program’s midwives collected cervical cells in a ThinPrep transport device. The midwives had undergone specific training before the new strategy was implemented. The other LHAs collected a double sample (Qiagen Standard Transport Medium for HPV DNA testing (Leinonen et al, 2009) plus a conventional smear for cytological triage).

Samples were first processed for HPV, with HPV-negative women referred to a new screening episode after 3 years. For HPV-positive women, a cytological slide was prepared and stained. Women with atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASC-US), low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (LSIL) or worse cytologies were directly referred for colposcopy. Women who tested HPV-positive and Pap-negative (HPV+/Pap−) were informed of the result by mail. A written invitation to repeat the HPV test was sent to them 12 months later. Women who tested HPV-negative were referred to a new screening after 3 years, whereas women with a positive HPV mRNA test were referred to colposcopy. The latter’s cytologies were processed and the related diagnoses were made available to the gynaecologists who performed the colposcopies.

Pap test-based screening

During the historical comparison period between 2009 and 2011, cervical samples were collected in liquid samples (ThinPrep) in Venice. Women with a LSIL or a worse cytology were directly referred for colposcopy. A triage with HPV testing of women with ASC-US was introduced in 2009, with women who tested negative at triage being referred to repeat the cytology after 1 year.

In the other LHAs, conventional smears were collected. Women with ASC-US, LSIL or worse cytology were directly referred for colposcopy.

In all LHAs, women with inadequate samples were invited to repeat the cytology and women negative for intraepithelial lesions or malignancy were referred to a new screening test after 3 years.

Molecular tests

The HPV mRNA tests were performed by the Pathology Unit of the Ospedale all’Angelo in Mestre.

Women with a negative HPV mRNA test were informed of the result by letter and referred to the next screening episode after 3 years.

The HPV DNA test used in the other pilot programs was the Hybrid Capture 2 test (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), with a relative light unit/positive control ratio ⩾1 as the positivity threshold. Molecular analyses were performed in the program’s reference laboratories, as described by Zorzi et al, 2013b.

Management of positive women and end points

All Pap tests were performed in the reference pathology units of the screening programmes. Throughout the entire study period, cytological triage was performed at the Mestre Pathology Unit in Venice. The women who tested HPV mRNA-positive had their cytology read by a cytologist who was not blinded to the HPV positivity. Diagnoses were reported according to the Bethesda System (Luff, 1992; Solomon et al, 2002; Herbert et al, 2007). Positive cytology (ASC-US or worse) were reviewed by the same cytologist and two pathologists using a multi-view microscope.

Colposcopies were performed in the reference clinics of the screening programmes. Colposcopy-guided biopsies were collected for all positive areas. Histological findings of colposcopy-directed biopsies were classified as negative, CIN1, CIN2, CIN3, or squamous cell or adeno cell carcinoma. Women with a CIN2+ diagnosis were referred for excisional treatment. Women with a negative colposcopy and/or biopsy were referred to a follow-up colposcopy 6 months later.

Main performance indicators

The following parameters were calculated both at baseline (including post-colposcopy follow up) and at the 1-year re-testing of women who were HPV+/Pap−, stratified by age (25–29, 30–34 and over 35 years):

-

Compliance with invitation (women screened/women invited);

-

HPV mRNA test positivity (HPV+ tests/HPV tests);

-

Pap smear distribution by diagnostic category;

-

Colposcopy referral rate (women screened who were referred for colposcopy/ all women screened);

-

Positive predictive value (PPV) for CIN2+ at colposcopy (colposcopies with histologically confirmed CIN2+/colposcopies);

-

CIN2+ DR (women with histologically confirmed CIN2+/screened women).

In order to assess the differences in background risk, we compared the Pap test detection and referral rates in the period before the introduction of the HPV test for women residing in Venice vs those in the areas covered by the four HPV DNA programs. Then we compared the results of the two HPV-based strategies by calculating the relative rates (RR) of the main indicators, with 95% confidence interval (CIs). The P-value was fixed at 0.05.

We have reported the results for women screened with the HPV mRNA test from October 2011 to May 2014, and who were followed up until May 31, 2015, in order to include the results of 1-year repeat for HPV+/Pap− women at the baseline.

Results

The HPV mRNA test program at baseline and at the 1-year repeat

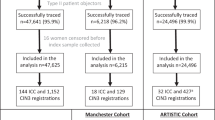

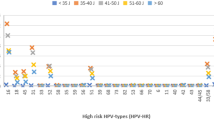

The study flowchart and principal data are reported in Figure 1. During the study period, 52 862 women were invited to participate in the screening programme. Of these, 23 217 complied with the invitation (45.2%) (Table 1). Six virgins underwent only a Pap smear. The HPV mRNA overall test positivity rate was 7.0%, with values decreasing from 15.5% in the group 25–29 years old to 3.4% in the group 60–64 years old (Figure 2A). The positivity rate in women aged 35–64 years was 5.7%.

Cumulative: baseline+1-year repeat after HPV+/pap−. Proportion of positive HPV tests at the baseline (%) (A) and cumulative detection rates of CIN2+ (‰) (B) in women screened with the HPV mRNA and the HPV DNA tests, by age. * standardised by age. Below the age strata, the number of screened women in each age stratum is reported.

The positivity rate of cytological triage was 53.1%. The referral rate to colposcopy at baseline was 3.9%, whereas 3.1% of the women screened were referred to a 1-year repeat. The CIN2+ DR was 4.4‰ at baseline, and was highest in the youngest age group (11.7‰), decreasing with age. The DR in the group aged 35–64 years was 3.5‰. Overall, the PPV for CIN2+ at colposcopy was 13.5%.

Among HPV+/pap− women at baseline, compliance with the invitation to repeat the HPV after 1 year was 81.7% (Table 1). Of these, there were 51.2% with a persistent infection at repeat who were invited to a colposcopy. The CIN2+ DR was 0.7 per 1000 screened women, with higher values in the younger age groups (25–29 years: 1.1‰, 30–34 years: 1.6‰ and 35–64 years: 0.6‰).

Comparison of cytology-based programs before the introduction of the primary HPV mRNA and HPV DNA tests

Before the introduction of the HPV mRNA test, compliance with the cytological screening invitation in Venice was 35.6% and was significantly lower than in the areas where the HPV DNA was introduced later (48.0, P<0.0001) (Table 2). The proportion of ASC-US+ was higher in Venice (3.7% vs 2.7%, P<0.0001) but after the ASC-US triage, the colposcopy referral rate was similar.

The CIN2+ DR was slightly but not significantly higher in Venice (RR 1.09, 95% CI 0.75–1.54).

Comparison between the HPV mRNA and the HPV DNA test programs

Comparing the HPV mRNA test program study results with the HPV DNA pilot programs, invitation compliance in Venice was confirmed as being lower (RR 0.80, 95% CI 0.78–0.81) (Table 1).

The baseline HPV test positivity rates were similar (RR 1.02; 95% CI 0.96–1.08), although women aged 35–64 years had higher rates with the HPV mRNA test (RR 1.16; 95% CI 1.09–1.25). Moreover, the cytological triage positivity rate was higher in the HPV mRNA test program (RR 1.38; 95% CI 1.25–1.52). At the 1-year repeat, the proportion of positive HPV mRNA tests was lower than for the HPV DNA tests (RR 0.76; 95% CI 0.63–0.92).

The HPV mRNA test program showed a significantly higher age-standardised CIN2+ DR at baseline (RR 1.50; 95% CI 1.19–1.88), as well as among women 35–64 years old (RR 1.46; 95% CI 1.08–1.95). At the 1-year repeat, its DR was not significantly lower (RR 0.70; 95% CI 0.40–1.16).

Thus, the cumulative (baseline+1-year repeat) DR was higher with the HPV mRNA test overall (RR 1.29; 95% CI 1.05–1.59) and in women of 35–64 years old (RR 1.30; 95% CI 1.00–1.69). Figure 2B shows that there was no excess of cumulative CIN2+ DR with the HPV mRNA test in women older than 50 years.

The proportion of all CIN2+ diagnosed at the 1-year repeat with the HPV mRNA test was significantly lower than the HPV DNA (14.4% vs 26.2%; RR 0.47; 95% CI 0.25–0.82).

Finally, the cumulative referral rate to colposcopy of the HPV mRNA test program demonstrates a small increment (5.1% vs 4.8%; RR 1.07; 95% CI 1.00–1.14).

Moving from a Pap test-based program to a HPV-based one, the colposcopy referral rate doubled in Venice (RR 2.02; 95% CI 1.82–2.25) and increased by 82% in the HPV DNA programs (RR 1.82; 95% CI 1.72–1.92) (Table 3). Similarly, the CIN2+ DR more than doubled both in Venice (RR 2.50; 95% CI 1.76–3.62) and in the HPV DNA programs (RR 2.31; 95% CI 1.90–2.81). Finally, the PPV for CIN2+ increased by ∼25% in both programmes (HPV mRNA program: RR 1.22; 95% CI 0.84–1.79; HPV DNA programs: RR 1.27; 95% CI 1.04–1.57).

Discussion

The Venice screening program concluded one screening round with HPV mRNA test as the primary screening tool. The results were substantially similar to those of the pilot programs in the same region, which used the HPV DNA test in the same period.

Diversely, the HPV prevalence and CIN2+ DR was higher than that reported by other European studies, possibly due to the inclusion of women aged 25–30 years.

As many studies reported a higher specificity for the HPV mRNA test compared with the HPV DNA tests (Monsonego et al, 2011; Monsonego et al, 2012; Cuzick et al, 2013; Nieves et al, 2013; Heideman et al, 2013; Reid et al, 2015; Iftner et al, 2015), we expected to observe a lower referral rate in Venice. Surprisingly, we did not observe such an effect. On the other hand, the DR was highest in the programme using the HPV mRNA test than in the others. This result was surprising also because the HPV mRNA test has shown a lower sensitivity than the HPV DNA tests in most studies (Monsonego et al, 2011; Monsonego et al, 2012; Cuzick et al, 2013; Nieves et al, 2013; Heideman et al, 2013; Reid et al, 2015; Iftner et al, 2015) although not in all (Wu et al, 2010).

As reported by other Italian HPV-based screening pilot projects, we observed a higher participation in the programme compared with the historical participation rate in the Pap test screening program (Confortini et al, 2010; Zorzi et al, 2013b; Pasquale et al, 2015). The new test could be more appealing, making the public screening programme more competitive than the opportunistic screening in the private sector, which did not have the possibility to offer the HPV test at reasonable prices during the study period. Obviously, participation can increase only if effective communication strategies are used. In Venice the invitation letter was accompanied by an information leaflet about HPV testing. Furthermore, during the actual period of the study, a community-level HPV vaccination campaign was simultaneously conducted, which also disseminated information on the HPV virus and cervical cancer to mothers of girls targeted for vaccination.

Given the study’s non-randomised design, we cannot directly infer differences in the clinical accuracy of the two tests from differences in the detection and referral rates. In order to evaluate if the two target populations might differ in their baseline risk of infection and of pre-cancerous lesions, we compared the screening programmes’ main performance indicators for the period before the introduction of HPV tests as the first-line test. The comparison suggests a slightly higher CIN2+ risk in the Venice area, even if the difference could be attributed to a higher prevalence of abnormal cytology. The latter suggests a higher prevalence of HPV infections (Giorgi Rossi et al, 2012). This figure could also be the effect of differences in the interpretation of some cytological findings, that is, cytology specificity being highly dependent on the cytologist (Giorgi Rossi et al, 2011). However, the proportion of HPV-positive women among the ASC-US in 2010 and 2011 was ∼60%, suggesting that the Venice pathology unit’s cytologists had a specificity comparable to or even higher than that of the cytologists in the NTCC trial (Ronco et al, 2007) and the ALTS study (Solomon et al, 2001). Although big differences in HPV prevalence have been observed in Italy, surveys from nearby areas rarely showed large differences (Zorzi et al, 2013a, 2013b). Among programmes adopting the same test in the Veneto region, figures range from 6.0 to 7.5%. Furthermore, as the Venice participation rate was much lower than in the other LHAs, the target population invited to each round included a higher proportion of women who had never been or were underscreened. This situation may favour a higher prevalence of lesions in women screened in Venice. In conclusion, the comparison of the screening programmes’ performance in the two areas before the introduction of the HPV tests suggests a slightly higher risk of lesions and HPV infections in Venice.

In the light of these differences in background risk, any comparison of the HPV mRNA and HPV DNA tests must be interpreted cautiously.

Surprisingly, test positivity was slightly higher in Venice with the HPV mRNA test than in the HPV DNA programs. This is not expected for a test that has been reported to be more specific (Monsonego et al, 2011; Monsonego et al, 2012; Cuzick et al, 2013; Nieves et al, 2013; Heideman et al, 2013; Reid et al, 2015; Iftner et al, 2015). On the other hand, triage positivity among HPV-positive women was also higher, suggesting a more specific first-level test. The excess positivity rate was only for women over 35 years old, a group where persistent infection is usually proportionately higher. From our data, we can surmise that the advantage in the mRNA’s specificity, outside the research context, is not that high. In addition, the positivity rate can be higher than that of the HPV DNA even for a small increase in HPV prevalence. Other studies have quantified the gain in HPV mRNA test specificity as compared with DNA tests and found approximately a 15% decrease in test positivity in a screening population (Cuzick et al, 2013). Differences in HPV prevalence among Italian screening programs adopting the same HPV DNA test are definitely greater, ranging from 4–12% (Baussano et al, 2013; Ronco et al, 2015). Therefore, Venice’s slightly higher positivity as compared with neighbouring programmes cannot be considered anomalous, even if the HPV mRNA test is slightly more specific.

Venice’s DR was higher than in the HPV DNA-based programs, an unexpected result for a test that should have a minor or equal sensitivity than the HPV DNA according to its rationale and to most published studies (Monsonego et al, 2011; Monsonego et al, 2012; Cuzick et al, 2013; Nieves et al, 2013; Heideman et al, 2013; Reid et al, 2015; Iftner et al, 2015). It must be noted that recent studies have questioned whether the Aptima mRNA test is less sensitive than the HPV DNA tests especially for clinically relevant lesions (Haedicke and Iftner, 2016). Actually, we observed an excess in DR only among older women for whom regressive lesions are less frequent.

Our data suggest that if the HPV mRNA test is associated with a decrease in sensitivity, this decrease is likely to be quite small. In fact, when the programme shifted from cytology to the HPV mRNA test, the improvement in DR was similar to that of the neighbouring programmes that had adopted the HPV DNA.

Finally, the proportion of lesions found at the 1-year follow up was significantly lower than in the HPV DNA-based programs. This could be the effect of a less specific triage referring to immediate colposcopy in more than 50% of HPV mRNA women, or of a lower prospective sensitivity of the HPV mRNA test compared with the HPV DNA test. In fact, lesions detected at the 1-year follow up included small, cytologically negative lesions already present at baseline or lesions that had developed during the 12 months. The test’s different target could justify a lower sensitivity for the second type of lesions.

Conclusions

The results of a screening programme which adopted the HPV mRNA test as the primary screening tool followed by cytology triage were similar to those observed with the HPV DNA test. In comparison with the previous Pap test screenings, the CIN2+ DR increased 2.5 times and the referral rate doubled. Further research is needed to measure the test’s longitudinal sensitivity and to determine a safe and efficient screening interval.

Change history

23 August 2016

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Arbyn M, Anttila A, Jordan J, Ronco G, Schenck U, Segnan N, Wiener H, Herbert A, von Karsa L (2010) European guidelines for quality assurance in cervical cancer screening. Second edition-summary document. Ann Oncol 21: 448–458.

Arbyn M, Ronco G, Anttila A, CJLM Meijer, Poljak M, Ogilvie G, Koliopoulos G, Naucler P, Sankaranarayanan R, Peto J (2012) Evidence regarding HPV testing in secondary prevention of cervical cancer. Vaccine 30 (Suppl 5): F88–F99.

Arbyn M, Haelens A, Desomer A, Verdoodt F, Thiry N, Francart J, Hanquet G, Robays J (2015a) Cervical cancer screening program and Human Papillomavirus (HPV) testing, part II: update on HPV primary screening. Health Technology Assessment (HTA). Brussels: Belgian Health Care Knowledge Centre (KCE). KCE Reports 238: D/2015/10.273/17.

Arbyn M, Snijders PJ, Meijer CJ, Berkhof J, Cuschieri K, Kocjan BJ, Poljak M (2015b) Which high-risk HPV assays fulfil criteria for use in primary cervical cancer screening? Clin Microbiol Infect 21: 817–826.

Baussano I, Franceschi S, Gillio-Tos A, Carozzi F, Confortini M, Dalla Palma P, De Lillo M, Del Mistro A, De Marco L, Naldoni C, Pierotti P, Schincaglia P, Segnan N, Zorzi M, Giorgi-Rossi P, Ronco G (2013) Difference in overall and age-specific prevalence of high-risk human papillomavirus infection in Italy: evidence from NTCC trial. BMC Infect Dis 13: 238.

Coleman D, Day N, Douglas G, Farmery E, Lynge E, Philip J, Segnan N (1993) European guidelines for quality assurance in cervical cancer screening. Europe against cancer programme. Eur J Cancer 29A (Suppl 4): S1–S38.

Confortini M, Giorgi Rossi P, Barbarino P, Passarelli AM, Orzella L, Tufi MC (2010) Screening for cervical cancer with the Human papillomavirus test in an area of central Italy with no previous active cytological screening program. J Med Screen 17 (2): 79–86.

Cuzick J, Cadman L, Mesher D, Austin J, Ashdown-Barr L, Ho L, Terry G, Liddle S, Wright C, Lyons D, Szarewski A (2013) Comparing the performance of six human papillomavirus tests in a screening population. Br J Cancer 108: 908–913.

Giorgi Rossi P, Chini F, Bisanzi S, Burroni E, Carillo G, Lattanzi A, Angeloni C, Scalisi A, Macis R, Pini MT, Capparucci P, Guasticchi G, Carozzi FM Prevalence Italian Working Group HPV (2011) Distribution of high and low risk HPV types by cytological status: a population based study from Italy. Infect Agent Cancer 6: 2.

Giorgi Rossi P, Franceschi S, Ronco G (2012) HPV prevalence and accuracy of HPV testing to detect high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Int J Cancer 130: 1387–1394.

Gruppo Italiano Screening Citologico (GISCi) (2010) Raccomandazioni sul test HR-HPV come test di screening primario e rivisitazione del ruolo del Pap test. Belluno: Evidenzia, pp. 19 (Italian). Available at www.gisci.it/documenti/documenti_gisci/documento_hpv.pdf (accessed August 7 2015).

Health Council of the Netherlands (2011) Population screening for cervical cancer. The Hague: Health Council of the Netherlands; publication no. 2011/07E.

Haedicke J, Iftner T (2016) A review of the clinical performance of the Aptima HPV assay. J Clin Virol 76 (Suppl 1): S40–S48.

Heideman DA, Hesselink AT, van Kemenade FJ, Iftner T, Berkhof J, Topal F, Agard D, Meijer CJ, Snijders PJ (2013) The Aptima HPV assay fulfills the cross-sectional clinical and reproducibility criteria of international guidelines for human papillomavirus test requirements for cervical screening. J Clin Microbiol 51: 3653–3657.

Herbert A, Bergeron C, Wiener H, Schenck U, Klinkhamer P, Bulten J, Arbyn M (2007) European guidelines for quality assurance in cervical cancer screening: recommendations for cervical cytology terminology. Cytopathology 18: 213–219.

IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Human papillomaviruses (2005) IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans Vol 90. Lyon: IARC.

Iftner T, Becker S, Neis KJ, Castanon A, Iftner A, Holz B, Staebler A, Henes M, Rall K, Haedicke J, von Weyhern CH, Clad A, Brucker S, Sasieni P (2015) Head-to-head comparison of the RNA-based aptima human papillomavirus (HPV) assay and the DNA-based hybrid capture 2 HPV test in a routine screening population of women aged 30 to 60 years in Germany. J Clin Microbiol 53: 2509–2516.

Leinonen M, Nieminen P, Kotaniemi-Talonen L, Malila N, Tarkkanen J, Laurila P, Anttila A (2009) Age-specific evaluation of primary human papillomavirus screening vs conventional cytology in a randomized setting. J Natl Cancer Inst 101: 1612–1623.

Luff RD (1992) The Bethesda System for reporting cervical-vaginal cytologic diagnoses: a report of the 1991 Bethesda Workshop. Hum Pathol 23: 719–721.

Meijer CJ, Berkhof J, Castle PE, Hesselink AT, Franco EL, Ronco G, Arbyn M, Bosch FX, Cuzick J, Dillner J, Heideman DA, Snijders PJ (2009) Guidelines for human papillomavirus DNA test requirements for primary cervical cancer screening in women 30 years and older. Int J Cancer 124 (3): 516–520.

Monsonego J, Hudgens MG, Zerat L, Zerat JC, Syrjänen K, Halfon P, Ruiz F, Smith JS (2011) Evaluation of oncogenic human papillomavirus RNA and DNA tests with liquid-based cytology in primary cervical cancer screening: the FASE study. Int J Cancer 129 (3): 691–701.

Monsonego J, Hudgens MG, Zerat L, Zerat JC, Syrjänen K, Smith JS (2012) Risk assessment and clinical impact of liquid-based cytology, oncogenic human papillomavirus (HPV) DNA and mRNA testing in primary cervical cancer screening (the FASE study). Gynecol Oncol 125 (1): 175–180.

Nieves L, Enerson CL, Belinson S, Brainard J, Chiesa-Vottero A, Nagore N, Booth C, Pérez AG, Chávez-Avilés MN, Belinson J (2013) Primary cervical cancer screening and triage using an mRNA human papillomavirus assay and visual inspection. Int J Gynecol Cancer 23 (3): 513–518.

Pasquale L, Giorgi Rossi P, Carozzi F, Pedretti C, Ruggeri C, Scalvinoni V, Cotti Cottini M, Tosini A, Morana C, Chiaramonte M, Sacristani MF, Cirelli R, Chiudinelli D, Piccolomini M, Marchione R, Romano L, Domenighini S, Pieracci G, Confortini M (2015) Screening for cervical cancer with HPV testing: performance and organizational impact of the Valcamonica screening programme, Northern Italy. J Med Screen 22 (1): 38–48.

Reid JL, Wright TC Jr, Stoler MH, Cuzick J, Castle PE, Dockter J, Getman D, Giachetti C (2015) Human papillomavirus oncogenic mRNA testing for cervical cancer screening: baseline and longitudinal results from the CLEAR Study. Am J Clin Pathol 144 (3): 473–483.

Ronco G, Cuzick J, Segnan N, Brezzi S, Carozzi F, Folicaldi S, Dalla Palma P, Del Mistro A, Gillio-Tos A, Giubilato P, Naldoni C, Polla E, Iossa A, Zorzi M, Confortini M, Giorgi-Rossi P the NTCC Working Group (2007) HPV triage for low grade (L-SIL) cytology is appropriate for women over 35 in mass cervical cancer screening using liquid based cytology. Eur J Cancer 43: 476–480.

Ronco G, Giorgi-Rossi P, Carozzi F, Confortini M, Dalla Palma P, Del Mistro AR, Ghiringhello B, Girlando S, Gillio-Tos A, De Marco L, Naldoni C, Pierotti P, Rizzolo R, Schincaglia P, Zorzi M, Zappa M, Segnan N, Cuzick J the New Technologies for Cervical Cancer screening (NTCC) Working Group (2010) Efficacy of human papillomavirus testing for the detection of invasive cervical cancers and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 11 (3): 249–257.

Ronco G, Biggeri A, Confortini M, Naldoni C, Segnan N, Sideri M, Zappa M, Zorzi M, Calvia M, Accetta G, Giordano L, Cogo C, Carozzi F, Gillio Tos A, Arbyn M, Mejier CJ, Snijders PJ, Cuzick J, Giorgi Rossi P (2012) [Health technology assessment report: HPV DNA based primary screening for cervical cancer precursors]. Epidemiol Prev 36 (3–4 Suppl 1): e1–e72.

Ronco G, Dillner J, Elfström KM, Tunesi S, Snijders PJ, Arbyn M, Kitchener H, Segnan N, Gilham C, Giorgi-Rossi P, Berkhof J, Peto J, Meijer CJ International HPV screening working group (2014) Efficacy of HPV-based screening for prevention of invasive cervical cancer: follow-up of four European randomised controlled trials. Lancet 383: 524–532.

Ronco G, Giorgi-Rossi P, Giubilato P, Del Mistro A, Zappa M, Carozzi F the HPV screening survey working group (2015) A first survey of HPV-based screening in routine cervical cancer screening in Italy. Epidemiol Prev 39: 77–83.

Sankaranarayanan R, Nene BM, Shastri SS, Jayant K, Muwonge R, Budukh AM, Hingmire S, Malvi SG, Thorat R, Kothari A, Chinoy R, Kelkar R, Kane S, Desai S, Keskar VR, Rajeshwarkar R, Panse N, Dinshaw KA (2009) HPV screening for cervical cancer in rural India. N Engl J Med 360: 1385–1394.

Solomon D, Schiffman M, Tarone R ALTS Study group (2001) Comparison of three management strategies for patients with atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance: baseline results from a randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst 93: 293–299.

Solomon D, Davey D, Kurman R, Moriarty A, O'Connor D, Prey M, Raab S, Sherman M, Wilbur D, Wright T Jr, Young N Forum Group Members; Bethesda 2001 Workshop (2002) The 2001 Bethesda System: terminology for reporting results of cervical cytology. JAMA 287: 2114–2199.

von Karsa L, von Karsa L, Arbyn M, H, Dillner J, Dillner L, Franceschi S, Patnick J, Ronco G, Segnan N, Suonio E, Törnberg S, Anttila A (2015) European guidelines for quality assurance in cervical cancer screening. Summary of the supplements on HPV screening and vaccination. Papillomavirus Res 1: 22–31.

Wu R, Belinson SE, Du H, Na W, Qu X, Wu R, Liu Y, Wang C, Zhou Y, Zhang L, Belinson JL (2010) Human papillomavirus messenger RNA assay for cervical cancer screening: the Shenzhen Cervical Cancer Screening Trial I. Int J Gynecol Cancer 20: 1411–1414.

Zorzi M, Fedato C, Cogo C, Baracco S, Da Re F (2013a) I programmi di screening oncologici del Veneto Rapporto 2011-2012 Padova: CLEUP, (Italian) Available at www.registrotumoriveneto.it/screening/presentazione.php (accessed August 7 2015).

Zorzi M, Del Mistro A, Farruggio A, de' Bartolomeis L, Frayle-Salamanca H, Baboci L, Bertazzo A, Cocco P, Fedato C, Gennaro M, Marchi N, Penon M, Cogo C, Ferro A (2013b) Use of a high-risk human papillomavirus DNA test as the primary test in a cervical cancer screening programme: a population-based cohort study. BJOG 120: 1260–1268.

Acknowledgements

The study was approved on 16 September, 2010 by the Institutional Ethics Committee in the Province of Venice, Decision number 2 CEP/2010.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Dr Paolo Giorgi Rossi, the Principal Investigator of an independent study funded by the Italian Ministry of Health, is negotiating with Roche Diagnostics, Hologic-Genprobe, Qiagen and Abbott to obtain reagents at a reduced price or free of charge. The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 4.0 Unported License.

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 4.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Maggino, T., Sciarrone, R., Murer, B. et al. Screening women for cervical cancer carcinoma with a HPV mRNA test: first results from the Venice pilot program. Br J Cancer 115, 525–532 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2016.216

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2016.216

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Meta-analysis of downregulated E-cadherin as a diagnostic biomarker for cervical cancer

Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics (2022)