Abstract

Background:

For patients with symptoms of possible cancer who do not fulfil the criteria for urgent referral, initial investigation in primary care has been advocated in the United Kingdom and supported by additional resources. The consequence of this strategy for the timeliness of diagnosis is unknown.

Methods:

We analysed data from the English National Audit of Cancer Diagnosis in Primary Care on patients with lung (1494), colorectal (2111), stomach (246), oesophagus (513), pancreas (327), and ovarian (345) cancer relating to the ordering of investigations by the General Practitioner and their nature. Presenting symptoms were categorised according to National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance on referral for suspected cancer. We used linear regression to estimate the mean difference in primary-care interval by cancer, after adjustment for age, gender, and the symptomatic presentation category.

Results:

Primary-care investigations were undertaken in 3198/5036 (64%) of cases. The median primary-care interval was 16 days (IQR 5–45) for patients undergoing investigation and 0 days (IQR 0–10) for those not investigated. Among patients whose symptoms mandated urgent referral to secondary care according to NICE guidelines, between 37% (oesophagus) and 75% (pancreas) were first investigated in primary care. In multivariable linear regression analyses stratified by cancer site, adjustment for age, sex, and NICE referral category explained little of the observed prolongation associated with investigation.

Interpretation:

For six specified cancers, investigation in primary care was associated with later referral for specialist assessment. This effect was independent of the nature of symptoms. Some patients for whom urgent referral is mandated by NICE guidance are nevertheless investigated before referral. Reducing the intervals between test order, test performance, and reporting can help reduce the prolongation of primary-care intervals associated with investigation use. Alternative models of assessment should be considered.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

There are an estimated 300 million consultations in general practice in England annually (90% of all patient contacts with health care) (Hippisley-Cox and Vinogradova, 2009). A major challenge for primary-care clinicians is to discriminate, often on the basis of undifferentiated or non-specific symptoms, between patients with self-limiting illness and those with significant disease. Cancer symptoms typically have low positive predictive values and present a particular challenge in this respect (Hamilton, 2009). Nevertheless, prompt identification and referral for investigation of patients with suspected cancer is a major public and policy concern (Department of Health, 2007; Macmillan Cancer Support, 2014), based on a widely held view that delays have a detrimental effect on outcome. The evidence is not as yet definitive. Although some studies have shown an association between longer time to diagnosis and poorer clinical outcomes (Richards et al, 1999; Torring et al, 2013), confounding by patients with advanced disease at presentation can make their interpretation problematic (Neal, 2009). Meanwhile, prolonged time to diagnosis results in psychological distress and sub-optimal patient experience (Risberg et al, 1996; Rarer Cancer Foundation, 2011). Clinical guidance for general practitioners (GPs) on high-risk features warranting urgent referral for suspected cancer has been produced in a number of countries, and in England by NICE in 2005 (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2005)). Many cancer patients, however, present to their GP with lower-risk features (Hamilton, 2010). A more recent approach to improving cancer outcomes in England has been to increase access for GPs to diagnostic tests supported by guidance on their use (Department of Health, 2012a).

In the 3 months before diagnosis, Danish patients with cancer have around 10 times as many diagnostic investigations as the reference population, some instigated by GPs (Christensen et al, 2012). Most studies of GPs’ use of investigations has addressed issues of test use (Jellema et al, 2010) and efficiency (Verstappen et al, 2003; Schoen et al, 2004). It is uncertain, however, whether initial investigation of cancer symptoms in primary care delays referral for specialist assessment. This question is central to clinical practice and cancer diagnosis.

In order to answer the question of whether, in patients with symptoms suggestive of cancer, primary-care investigations are associated with less prompt referral, we analysed data from the English National Audit of Cancer Diagnosis in Primary Care, conducted during 2009/10 and containing information on 18 879 patients diagnosed with cancer in that period (Rubin et al, 2011).

Patients and methods

The methods used in collection of the source data are described in detail elsewhere (Rubin et al, 2011). In brief, anonymous data were collected by GPs or other primary-care professionals in an estimated total of 1170 general practices (∼14% of all practices in England) that participated voluntarily in an audit of cancer diagnosis in primary care. All patients of those practices, who were diagnosed with cancer, typically during a defined period of up to 12 months, were included in the audit. Patients with screen-detected cancer, in situ cancer, and non-melanoma skin cancer were excluded. The age, gender, and cancer diagnosis case-mix of the audited population is representative of the population-based cancer incidence statistics, and participating practices are similar to non-participating practices in their (former) cancer networks (Lyratzopoulos et al, 2013a).

We analysed data on patients with lung (1494), colorectal (2111), stomach (246), oesophagus (513), pancreas (327), and ovarian (345) cancer. These six cancer sites were selected because they each have a range of presenting symptoms from high to low risk, and because for each there is one or more investigation that may be appropriately ordered as part of the patient’s assessment in primary care and that is generally available to GPs in England.

We analysed data on patients aged 15 years or older with completely observed information on primary-care interval values from 0 to 730 days (Lyratzopoulos et al, 2013b). We defined primary-care interval as the period in days from first presentation to a GP with a relevant symptom to the date of first specialist referral for further assessment. The audit also collected the date of the first appointment with a specialist, but did not collect the date of diagnosis.

Gender and age were recorded from the patient medical records, the latter categorised for this study into six groups 15–44, 45–54, 55–64, 65–74, 75–4 and 85+.

Data were extracted from the audit data set in relation to two questions ‘Did the GP order any investigations’ and ‘If yes, please list the investigations in order’. Practice staff were asked to identify any investigations undertaken prior to referral. Responses to the first question were coded as yes, no, or missing, and responses to the second question were used to create five binary variables coding whether or not the patient had had any of five common investigations: blood test; chest X-ray; ultrasound scan; CT or MRI scan; endoscopic investigation.

Clinical presentation

Free text audit records in response to the question ‘What was the main presenting symptom?’ were categorised in two stages. First, and separately by cancer, the presenting symptom(s) was classified into between 20 and 37 groups (Appendix Table A1). These were agreed by three clinicians (GPR, RDN, GL) and then independently assigned by them. Disagreements were resolved by discussion between coders. Where more than one symptom was described, the main symptom was taken as the first stated, unless a NICE Clinical Guideline (CG)27-mandated (‘alarm’) symptom appeared later in the list.

Second, patients were classified on the basis of their presenting symptom(s) and age into five groups according to CG27; mandated referral; possibly mandated referral (insufficient information provided on qualifying conditions (e.g., severity, duration, frequency) to be definitive); mandated investigation; possibly mandated investigation (as above); no mandated action. Some presenting symptoms (e.g., ascites, haematemesis) were not specifically mentioned in CG27 as requiring urgent referral, but the clinical consensus was that this would be best practice. These were included in the ‘mandated referral’ group. Coding was age specific for those symptoms for which CG27 recommendations were age-conditional. For multivariable analysis, ‘possible referrals’ were grouped with ‘no action’ for ovarian and oesophageal cancers because of small numbers.

Statistical analysis

We describe the primary-care interval distribution using the mean, median, 25th, 75th, and 90th centiles. Stratified by cancer diagnosis, we calculated the percentages of patients investigated by their GP in each of the five NICE CG27 referral recommendation groups.

We calculated the mean difference in primary-care interval among those patients investigated in primary care and those who were not. To determine whether the association between primary-care investigations and primary-care interval can be attributed to different clinical presentations (i.e., whether patients who are most likely to be investigated are simply those who present with non-specific symptoms and have a longer primary-care interval for this reason), we used linear regression to estimate the mean difference in primary-care interval by investigation status, adjusting for age, gender, and the NICE referral category, separately by cancer.

95% Confidence intervals were estimated using bias corrected and accelerated bootstrap estimation, and where they exclude zero, the differences between the two groups were taken to be significant at P<0.05. Analyses were repeated for 99.99% confidence intervals.

We performed a number of sensitivity analyses investigating the impact of how the primary-care interval, primary-care investigation use and clinical presentation were parameterised (see Appendix Tables for details). Further, we performed a supplementary analysis to explore the possibility that primary-care investigation may decrease the referral interval (defined as the number of days between referral from primary care and first patient contact in secondary care). We therefore explored the adjusted association of overall pre-hospital interval (defined as the total time from first presentation to primary care to first being seen in secondary care, i.e., referral interval plus primary-care interval) with investigation use.

Results

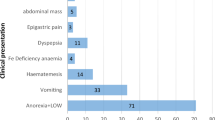

The derivation of the analysis sample is shown in Figure 1. In descriptive analyses, primary-care investigations were undertaken in 3198/5036 of included cases (64%), ranging from 43% for oesophageal cancer to 80% for lung cancer. The median primary-care interval across all six cancer sites was 16 (IQR 5–45) days for those who had one or more investigation, and 0 (IQR 0–10) days for those who had no investigation. The corresponding mean intervals were 41 days and 17 days, and did not differ by age or gender. The difference in the median interval by investigation status was considerably greater at the 75th (10 days non-investigated, 44 days investigated patients) and 90th centiles (45 days and 106 days, respectively) (Table 1).

In unadjusted analyses, individual investigations lengthened the mean primary-care interval by between 5 days (chest X-ray) and 32 days (endoscopy), whereas undertaking more than one test in primary care added a mean of 8 days (Table 2). For individual cancer sites, any investigation significantly extended the mean primary-care interval by between 20 days (ovarian) and 30 days (stomach) (Table 2). When individual cancers were considered by NICE referral category, investigation was more likely if NICE CG27 mandated this or if no action was mandated. The proportion of patients presenting with symptoms for which NICE CG27 mandates urgent referral was 10%, 9%, 5%, 64%, 24%, and 37% for colorectal, ovarian, lung, oesophageal, pancreatic, and stomach cancer, respectively. Nevertheless, a substantial proportion of patients whose symptoms mandated urgent referral were investigated in primary care, ranging from 37% (oesophagus) to 75% (pancreas) (Table 3).

In linear regression analyses, stratified by cancer, that adjusted for age, sex, and the NICE referral category, adjustment for these factors explained very little of the mean observed additional days associated with investigation, but the effect for pancreatic cancer ceased to be significant (Table 4). Alternative parameterisations of the primary-care interval, investigation use, or clinical presentation categories made minimal difference to these findings (Appendix Tables A3–A5).

Among those patients for whom data on number of consultations prior to referral were available, 965/2095 (46.1%) of those consulting once were investigated, while 1058/1240 (85.3%) of those consulting 3+ times were investigated.

Finally, in order to address the possibility that longer primary-care intervals might be offset by shorter referral intervals, we examined the association between investigations in primary care and the combined primary care and referral interval (i.e., from first presentation in primary care to first being seen in a specialist clinic). For all cancers, except pancreatic cancer, the pre-hospital interval is longer among investigated patients, compared with those who were not investigated. We find no evidence that longer primary-care intervals are offset by shorter referral intervals in patients who are investigated in primary care (Appendix Table A6). Because date of diagnosis did not form part of the data items collected for the audit, we were unable to examine the effect of investigations on total diagnostic interval.

Discussion

We found that for six specified cancers, investigation in primary care of the presenting symptom(s) was associated with later referral for specialist assessment. This difference in the mean primary-care interval ranged from an additional 20 to 30 days depending on the cancer site, and was independent of whether the patient presented with alarm symptoms. For four of the six cancers studied, the difference increased with the number of tests undertaken.

The principle that patients with symptoms are initially assessed in primary care in order that only a proportion are then more extensively assessed by specialists (the gatekeeping function) is a key feature of health-care systems in which primary care features strongly. It contributes to their better health outcomes and efficiencies (Starfield et al, 2005), although an ecological association with poorer cancer 1-year survival has also been described (Vedsted and Olesen, 2011). Investigation in primary care is most strongly associated with perceived medical need, although a minority of investigations are a consequence of patient preference (Little et al, 2004). Where the alternative is specialist referral, investigation in primary care may result in the primary-care interval being prolonged, since additional consultations are needed to communicate results, and multiple consultations are associated with longer primary-care intervals (Lyratzopoulos et al, 2013b). We found that 85% of patients consulting three or more times had undergone investigation, compared with 46% of those consulting once. The literature is sparse on the effect of investigations in primary care on time to diagnosis, although a study of patients with colorectal cancer found that those who were not investigated by the faecal occult blood test had a significantly shorter median diagnostic interval than those who were (Hogberg et al, 2013). Further, a qualitative study of patients with testicular cancer identified waiting time for GP-requested ultrasonography as a factor in late diagnosis (Chapple et al, 2004). However, failure to investigate may be also associated with referral being deferred. In a study of GP-reported quality deviations in 5711 patients with cancer, failure to order relevant investigations was associated with a prolonged diagnostic interval (Jensen et al, 2014), whereas diagnostic delay for tuberculosis has been associated with failure of the first doctor consulted to order a sputum test or chest X-ray (Calder et al, 2000).

Strategies have been developed to expedite the investigation of patients with symptoms that could indicate cancer. In Denmark, ambulatory care facilities exist for the prompt investigation of patients with non-specific symptoms, alongside an urgent referral pathway for those with higher-risk symptoms (Danish National Board of Health, 2010) Walk-in access to chest X-ray for symptomatic members of the public aged >50 years has been provided through a local initiative in Leeds, UK, resulting in 8.6% of all community-ordered chest X-rays being taken this way (Cheyne et al, 2012). Dedicated centres that allow patients to access specialist assessment without physician referral have also been proposed by a panel of cancer experts in the United States, as a response to their Institute of Medicine report ‘Crossing the Quality Chasm’ (Bowles et al, 2008). The initiatives described address a range of constraints to prompt diagnosis, and they operate within complex health systems. Their impact can only be fully understood in the context of the overall diagnostic pathway, something we were unable to do in this study.

Strengths and limitations

This is the first study to explicitly determine the effect of GP-initiated investigations on speed of referral for specialist assessment. Its strengths include the relatively large number of cases for each cancer site, the completeness of data on presenting symptom(s) and consultations, and the direct extraction of information from the primary-care record. The study team included experienced clinicians, ensuring that the complex task of coding clinical data was accurately completed.

There are several limitations that we acknowledge. Because participation of general practices in the audit was voluntary and potentially biased towards those most interested in cancer care, the findings may represent ‘better’ practice. However, the audit patient population was similar to the incident cancer cases in England (Rubin et al, 2011) while the characteristics of participating practices were similar to non-participating practices of the same (former) cancer network (Lyratzopoulos et al, 2013b). Nevertheless, these practices may have been more interested in cancer diagnosis and management and more likely to investigate patients with suspicious symptoms. Practices were typically required to audit a continuous sample of cases occurring in a specified period, and there was no evidence of significant exclusion of cases (Rubin et al, 2011).

Data were extracted from clinical records and hospital correspondence. There was no validation of the data, but in all cases data were reviewed at a practice meeting and checked for completeness and face validity by a cancer network clinical lead. There is scope for errors of interpretation during data extraction, for example, in deciding on the date of first consultation. The potential sources of error in studies of diagnostic intervals have been well described (Weller et al, 2012), but the methodology used by the audit conformed to best practice in the field Weller et al, 2012). Finally, 1100 (17.9%) cases were excluded because both of the dates required to estimate the primary-care interval were not available. Many of these were patients whose pathway to diagnosis bypassed primary care, for example, through direct presentation to an emergency department. Others may have been seen by the GP, but the omission of dates of the first encounter and/or referral was not identified during the checking process prior to submission of data to the audit.

All investigations included were part of the primary-care appraisal process, but no judgement was made on their appropriateness or their context within the episode of care. It is possible that some were unhelpful or irrelevant to the diagnostic process and unnecessarily prolonged the primary-care interval. Details of the precise nature of blood or urine tests or the sites examined by CT, MRI, or endoscopy were not a specific requirement of practices participating in the audit.

Because the audit data were provided in an anonymous form, we were unable to link them to cancer registration and hospital record-derived data. This would have allowed us to determine, for those patients not investigated in primary care, whether investigation(s) were then undertaken in secondary or tertiary care and the effect of investigations in different settings on the total diagnostic interval. However, we observed that use of investigations, although adding to the length of the primary-care interval, did not result in a shorter referral interval. Moreover, for the hypothesis to be true that patients investigated in primary-care experience shorter secondary-care delays, and therefore no overall lengthening of the total diagnostic interval, either or both of the referral interval and the within-hospital interval to diagnosis would need to be substantially shorter for those patients with primary-care investigations compared with those without. These conditions are unlikely. First, we have observed a net lengthening of referral interval resulting from investigations for five out of six cancers. Second, as use of investigations is associated with extending of the primary-care interval by a median of +16 days and a mean of +24 days, within-hospital diagnostic processes would need to be extraordinarily fast to compensate for these prolonged intervals. It should also be noted that in 2011/12 87.3% of patients commenced treatment within 62 days of referral, and 98.4% commenced treatment within 31 days of a diagnosis being made (Department of Health, 2012b). Moreover, the most frequent primary-care investigations were blood tests and chest X-rays, tests that do not typically provide the definitive diagnostic information necessary to establish the diagnosis of cancer, and would be unlikely to result in any substantial shortening of diagnostic intervals within secondary or tertiary care.

We selected the NICE referral category as our primary method for categorising patients’ presenting symptoms. We adjusted for symptom status using a range of complementary analytical approaches, all of which indicated that the degree of confounding by symptom status (in respect of the association between investigation and prolonged primary-care interval) is trivial. In other words, whether patients present with non-specific symptoms or obvious alarm symptoms, investigations are always associated with a longer primary-care interval.

Implications for practice

Our findings are generalisable to health systems in which GPs act as gatekeepers to specialist care, but may be modified by differences in access to diagnostic tests. A substantial proportion of patients underwent investigation when their symptoms fulfilled NICE CG27 criteria for urgent referral. There are several possible explanations for this. Disparaging views from specialists about ‘abuse’ by GPs of the urgent referral pathway may make some prefer to have additional evidence in the form of a confirmatory test result before making a referral (Mathew and Desai, 2009). The NICE criteria typically represent a risk of cancer in the region of 5–10%, the large majority not having the disease, and some GPs may use investigations as means of increasing the probability of cancer prior to making a decision about referral. It is also possible that some patients present in a context that causes the GP to modify their preferred course of action. For example, the patient may have been investigated in the past for the same problem, have severe co-morbidities, or may be reluctant to be referred to a specialist. Some GPs may consider it desirable, or have been advised that it is, for the results of baseline investigations to be available at the first specialist attendance (Barking, Havering and Redbridge University Hospital, 2014). Significant event analyses and case-note review studies are required to further establish the circumstances surrounding such ‘guideline violations’ (Mitchell et al, 2013; Singh et al, 2013).

Finally, certain investigations available to GPs are the definitive diagnostic tests, e.g., gastroscopy for suspected oesophagogastric cancer, and may be as readily available in primary as in specialist care. Other diagnostic tests, however, take longer to complete when ordered from primary care and may not be sufficiently comprehensive. In England, the median time from request to test for non-obstetric ultrasound investigation is longer for GP requests (19–27 days) than for all request sources combined (12–16 days) (NHS England, 2013). If investigations are undertaken in patients for whom urgent referral is indicated, the request should be concurrent with referral.

Because tests ordered in primary care may not be done or reported as promptly as those ordered from secondary care, our findings point to a need for investigative services to be provided to a comparable standard regardless of source of request. This should be accompanied by improved systems in primary care that ensure that a patient is rapidly reviewed once results are received. They also provide some support for models of service delivery in England that permit the rapid specialist assessment of patients with lower-risk symptoms, either by a lowering of the thresholds for urgent (2 weeks) referral for suspected cancer or the provision of diagnostic centres.

Time may be used as a diagnostic tool in primary care (Heneghan et al, 2009). Symptoms are seen by GPs at an earlier stage of development than in secondary care, and time allows the clinician to observe whether relatively undifferentiated symptoms develop more specific characteristics or resolve spontaneously. Investigations may form a part of this temporising approach while also being part of a safety-netting strategy (Almond et al, 2009).

These findings are the first step in determining the most effective diagnostic strategies for managing patients with symptomatic presentation of cancer. It will be important to understand the impact of primary-care investigation on secondary-care intervals, since these may plausibly be shortened, and on total diagnostic delay. Until then, no firm recommendations can be made on the merits or demerits of primary-care investigation. There is a need to understand the comparative clinical and health economic efficiency of strategies that encourage early primary-care investigation, compared with those that encourage either expectant management with limited testing and urgent referral if symptoms persist or worsen, or early referral without prior investigation.

References

Almond S, Mant D, Thompson M (2009) Diagnostic safety-netting. Br J Gen Pract 59: 872–874.

Barking, Havering and Redbridge University Hospital (2014) Guidelines for referral of suspected upper GI cancer http://www.bhrhospitals.nhs.uk/Downloads/services/bhrut-cancer-form-uppergi-0409.pdf.

Bowles EJA, Tuzzio L, Wiese CJ, Kirlin B, Greene SM, Clauser SB, Wagner EH (2008) Understanding high quality cancer care. Cancer 112: 934–942.

Calder L, Gao W, Simmons G (2000) Tuberculosis: reasons for diagnostic delay in Auckland. NZ Med J 113: 83–85.

Chapple A, Ziebland S, McPherson A (2004) Qualitative study of men’s perceptions of why treatment delays occur in the UK for testicular cancer. Br J Gen Pract 54: 25–32.

Cheyne L, Foster C, Lovatt V, Hewitt F, Cresswell L, Fullard B, Fear J, Darby M, Robertson R, Plant PK, Milton R, Callister MEJ (2012) Improved lung cancer survival and reduced emergency diagnoses resulting from an early diagnosis campaign in Leeds 2011. Thorax 67 (Suppl 2): A44.

Christensen KG, Fenger-Gron M, Flarup KR, Vedsted P (2012) Use of general practice, diagnostic investigations and hospital services before and after cancer diagnosis—a population-based nationwide registry study of 127000 incident adult cancer patients. BMC Health Serv Res 12: 224.

Danish National Board of Health (2010) Kræftplan III. Styrket indsats på kræftområdet – et sundhedsfagligt oplæg. The Danish National Board of Health: Copenhagen, Denmark.

Department of Health (2007) Cancer Reform Strategy. Department of Health: London, UK.

Department of Health (2012a) Direct Access to Diagnostic Tests for Cancer: Best Practice Referral Pathways for General Practitioners (Gateway Ref 16913). Department of Health: London, UK.

Department of Health (2012b) Waiting Times for Cancer Services 2011-2012. Department of Health: London, UK.

Hamilton W (2009) The CAPER studies: five case-control studies aimed at identifying and quantifying the risk of cancer in symptomatic primary care patients. Br J Cancer 101: S80–S86.

Hamilton W (2010) Cancer diagnosis in primary care. Br J Gen Pract 60: 121–128.

Heneghan C, Glasziou P, Thompson M, Rose P, Balla J, Lasserson D, Scott C, Perera R (2009) Diagnostic strategies used in primary care. BMJ 338: b946.

Hippisley-Cox J, Vinogradova Y (2009) Trends in Consultation Rates in General Practice 1995 to 2008: Analysis of the QResearch® database. NHS Information Centre: London.

Hogberg C, Karling P, Rutefgard J, Lilja M, Ljung T (2013) Immunochemical faecal occult blood tests in primary care and the risk of delay in the diagnosis of colorectal cancer. Scand J Primary Health Care 31: 209–214.

Jellema P, van der Windt D, Bruinvels DJ, Mallen CD, van Weyenberg SJ, de Vet HC (2010) Value of symptoms and additional diagnostic tests for colorectal cancer in primary care: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 340: 795.

Jensen H, Nissen A, Vedsted P (2014) Quality deviations in cancer diagnosis. BrJ Gen Pract 64: e92–e98.

Little P, Dorward M, Warner G, Stephens K, Senior J, Moore M (2004) Importance of patient pressure and perceived pressure and perceived medical need for investigations, referral, and prescribing in primary care: nested observational study. BMJ 328: 444.

Lyratzopoulos G, Abel GA, McPhail S, Neal RD, Rubin GP (2013a) Gender inequalities in the promptness of diagnosis of bladder and renal cancer after symptomatic presentation: evidence from secondary analysis of an English primary care audit survey. BMJ Open 3: e002861.

Lyratzopoulos G, Abel GA, McPhail S, Neal RD, Rubin GP (2013b) Measures of promptness of cancer diagnosis in primary care: secondary analysis of national audit data on patients with 18 common and rarer cancers. Br J Cancer 108: 686–690.

Macmillan Cancer Support (2014) Cancer in the UK. Macmillan Cancer Support: London, UK http://www.macmillan.org.uk/Documents/AboutUs/WhatWeDo/CancerintheUK2014.pdf.

Mathew A, Desai KM . An audit of urology two week wait referrals in a large teaching hospital in England. Ann R Coll Surg Engl (2009); 91: 310–312.

Mitchell ED, Rubin G, Macleod U . Understanding diagnosis of lung cancer in primary care: qualitative synthesis of significant event audit reports. Br J Gen Pract (2013); 63 (606): e37–e46.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2005) Clinical Guideline 27: Referral Guidelines for Suspected Cancer. NICE: London, UK.

Neal RD . Do diagnostic delays in cancer matter? Br J Cancer (2009); 101 (Suppl 2): S9–S12.

NHS England (2013) Diagnostic Imaging Dataset Statistical Release 2013. NHS England: London, UK.

Rarer Cancer Foundation (2011) Primary cause? An Audit of the Experience in Primary Care of Rarer Cancer Patientshttp://www.rarercancers.org.uk/images/stories/cdf/p8and9/primary%20cause%20-%20final.pdf.

Richards MA, Westcombe AM, Love SB, Littlejohns P, Ramirez AJ . Influence of delay on survival in patients with breast cancer: a systematic review. Lancet (1999); 353 (9159): 1119–1126.

Risberg T, Sørbye SW, Norum J, Wist EA . Diagnostic delay causes more psychological distress in female than in male cancer patients. Anticancer Res (1996); 16 (2): 995–999.

Rubin GP, Elliott K, McPhail S (2011) National Audit of Cancer Diagnosis in Primary Care. Royal College of General Practitioners: London, UK.

Schoen C, Osborn R, Huynh PT, Doty M, Davis K, Zapert K, Peugh J (2004) Primary care and health system performance: adults’ experiences in five countries. Health Affairs W4: 487–503.

Singh H, Giardina TD, Meyer AN, Forjuoh SN, Reis MD, Thomas EJ . Types and origins of diagnostic errors in primary care settings. JAMA Intern Med (2013); 173 (6): 418–425.

Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J (2005) Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Quarterly 83: 457–502.

Torring ML, Frydenberg M, Hansen RP, Olesen F, Vedsted P (2013) Evidence for increasing mortality with longer diagnostic intervals for five common cancers: a cohort study in primary care. Eur J Cancer 49: 2187–2198.

Vedsted P, Olesen F (2011) Are the serious problems in cancer survival partly rooted in gatekeeper principles? An ecologic study. Br J Gen Pract 61: e508–e512.

Verstappen WH, van der Wijden T, Sijbrandij J, Smeele I, Hermsen J, Grimshaw J, Grol RP (2003) Effect of a practice-based strategy on test ordering performance of primary care physicians: a randomised trial. JAMA 289: 2407–1412.

Weller D, Vedsted P, Rubin G, Walter FM, Emery J, Scott S, Campbell C, Andersen RS, Hamilton W, Olesen F, Rose P, Nafees S, Hiom S, Muth C, Beyer M, Neal RD (2012) The Aarhus Statement: improving design and reporting of studies on early cancer diagnosis. Br J Cancer 106: 1262–1267.

Acknowledgements

RDN receives funding from Public Health Wales and Betsi Cadwaladr University Health Board. GL is supported by a Post-Doctoral Fellowship by the National Institute for Health Research (PDF-2011-04-047). We are grateful to all primary-care professionals in participating practices for collecting, collating and submitting anonymous data to the National Audit of Cancer Diagnosis in Primary Care; Cancer Networks, the Royal College of General Practitioners and the National Cancer Action Team for supporting the audit, and the National Clinical Intelligence Network (NCIN) for providing the data. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the RCGP, the National Institute for Health Research or the Department of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

From March 2012 to March 2014 GPR was the Royal College of General Practitioners Clinical Lead for Cancer and was a national advocate for the role of the GP in cancer diagnosis. The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Author contributions

GPR, GL, RDN, GAA and CS designed the study. GL, GAA and CLS analysed the data and all authors interpreted it. GPR wrote the first draft with additions and revisions by all authors.

Appendix

Appendix

Sensitivity analysis

We performed several sensitivity analyses for key analytical aspects, using alternative parameterisations of the three variables:

-

Primary-care interval

-

Investigation use in primary care

-

Clinical presentation

Primary-care interval is positively skewed, with a large number of zero values. The analysis (presented in the main text) examines ‘mean differences’ in primary-care interval associated with investigation use. Although the use of bootstrap estimation means that inference is appropriate, we also performed a sensitivity analysis based on a binary categorisation of primary-care interval into 0–14 and 15+ days. Results are presented in Appendix Table A3.

Investigation use can be parameterised as a binary yes/no variable (as in the main text)—or as an ordered categorical variable based on the number of investigations (used in sensitivity analysis). Specifically, the number of investigations was parameterised as an ordered categorical variable (0, 1, 2 or more investigations) based on counts of the five individual investigations (blood tests, chest X-rays, ultrasound, CT/MRI, or endoscopy). Results are presented in Appendix Table A4.

In the main analysis presented, we adjust for clinical presentation using five groups based on NICE guideline referral categories (Appendix Table A2). In sensitivity analysis adjustment for clinical presentation was made on the basis of presenting symptom(s) (Appendix Table A1) and based on this classification, but allowing the effect of symptom to vary by age. We also explored adjusting for the more detailed 14-group classification based on NICE guidelines (Appendix Table A2). Results are presented in Appendix Table A6.

Supplementary analysis

We performed a supplementary analysis to explore the possibility that primary-care investigation may decrease the referral interval (defined as the number of days between referral from primary care and the first patient contact in secondary care). If this hypothesis were true, it might offset the differences in primary-care interval. We therefore explored the adjusted association of overall pre-hospital interval (defined as the total time from first presentation to primary care to first being seen in secondary care, i.e., referral interval plus primary-care interval) with investigation use. Results are presented in Appendix Table A6.

For ovarian and oesophageal cancers ‘possible referrals’ were grouped with ‘no action’ in multivariable analysis because of small numbers, similarly age 15–44 years is grouped with age 55–64 years for pancreatic cancer because of small numbers.

In order to address the possibility that longer primary-care intervals might be offset by shorter referral intervals among investigated patients, we examined the association between investigations in primary care and the referral interval, and the combined primary care and referral interval (i.e., from first presentation in primary care to first being seen in a specialist clinic).

Although the differences in referral interval among investigated and non-investigated patients are small they are positive for all cancers except for pancreatic (i.e., referral intervals are not shorter among investigated patients). Consequently, the pre-hospital interval is longer among investigated patients, compared with those who were not investigated for all cancers except pancreatic cancer. Therefore, overall there is no evidence that longer primary-care intervals are offset by shorter referral intervals among patients who were investigated in primary care.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 4.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Rubin, G., Saunders, C., Abel, G. et al. Impact of investigations in general practice on timeliness of referral for patients subsequently diagnosed with cancer: analysis of national primary care audit data. Br J Cancer 112, 676–687 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2014.634

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2014.634

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Protocol for a feasibility study incorporating a randomised pilot trial with an embedded process evaluation and feasibility economic analysis of ThinkCancer!: a primary care intervention to expedite cancer diagnosis in Wales

Pilot and Feasibility Studies (2021)

-

The burden of cancer on primary and secondary health care services before and after cancer diagnosis in New South Wales, Australia

BMC Health Services Research (2019)

-

Reimagining the diagnostic pathway for gastrointestinal cancer

Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology (2018)

-

Improving early diagnosis of symptomatic cancer

Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology (2016)