Abstract

Background:

Evidence concerning the influence of ethnic diversity on clinical encounters in cancer care is sparse. We explored health providers' experiences in this context.

Methods:

Focus groups were conducted with a purposeful sample of 106 health professionals of differing disciplines, in 18 UK primary and secondary care settings. Qualitative data were analysed using constant comparison and processes for validation.

Results:

Communication and the quality of information exchanged with patients about cancer and their treatment was commonly frustrated within interpreter-mediated consultations, particularly those involving a family member. Relatives' approach to ownership of information and decision making could hinder assessment, informed consent and discussion of care with patients. This magnified the complexity of disclosing information sensitively and appropriately at the end of life. Professionals' concern to be patient-centred, and regard for patient choice and autonomy, were tested in these circumstances.

Conclusion:

Health professionals require better preparation to work effectively not only with trained interpreters, but also with the common reality of patients' families interpreting for patients, to improve quality of cancer care. Greater understanding of cultural and individual variations in concepts of disclosure, patient autonomy and patient-centredness is needed. The extent to which these concepts may be ethnocentric and lack universality deserves wider consideration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Care involving health professionals and patients of differing culture and ethnicity is increasingly the norm in developed countries. Ethnic inequalities in health and health care across disease settings present many challenges (Davey Smith et al, 2000; Smedley et al, 2003). Disparities in care of cancer and its outcomes for minority ethnic groups are no exception (Selby, 1996). These include, for example, ethnic differences in receipt of appropriate tests (McMahon et al, 1999), analgesia (Bernabei et al, 1998) and access to palliative care (Gaffin et al, 1996; Karim et al, 2000; Ahmed et al, 2004; Koffman et al, 2007). Such disparities may be associated with higher cancer mortality and lower survival (Bach et al, 1999; Ward et al, 2004).

Although cancers appear less common in minority ethnic groups, cancer is the foremost or second most common cause of death across virtually all populations (Bhopal and Rankin, 1996). Given the relatively young age structure of many minority populations in Western societies, and their adoption of indigenous lifestyle, such as diet and smoking, their experience of cancer and associated health-care needs can also be expected to rise in coming decades (Wild et al, 2006).

As part of informing strategies to respond, the influence of cultural diversity on day-to-day clinical encounters requires further study (Smedley et al, 2003). Patients' understanding and preferences for care should be based on appropriate exchange of information with health professionals. However, the acquisition and use of such information may be influenced by the context and process of communication. In the UK, National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) Cancer Services Guidance (2004) underlined the need for cancer care practitioners to develop skills in communication generally, and noted professionals may be poorly skilled in communicating effectively in ethnically diverse settings. However, there is a surprising lack of relevant published data on how professionals perceive and experience such encounters to inform practice or policy (Skelton et al, 2001; Smedley et al, 2003).

This qualitative study formed part of a wider initiative to enhance health professionals' responses to cancer and ethnic diversity (Kai, 2005). This has identified professionals' uncertainty and apprehension in responding to the needs of patients of differing ethnicities to their own, and how this can create a disabling hesitancy and inertia in their clinical practice (Daniels and Swartz, 2007; Kai et al, 2007). We aimed to explore health professionals' experiences of caring for patients with cancer from diverse ethnic communities to inform practice and quality of care interventions. This paper reports data on the contemporary practical challenges of communication, disclosure and patient autonomy faced by professionals in providing cross-cultural cancer care.

Methods

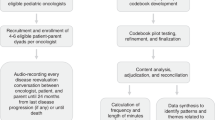

The study protocol was reviewed by a UK multi-centre research ethics committee, which had no ethical objections. Participants were sampled purposefully from a range of health service settings across the West and East Midlands regions of the UK. They were chosen to include health professionals of differing disciplines and cancer care settings, with varying experience of working with ethnically diverse patients, serving populations with varying minority ethnic composition (low, average or high proportions of local community). Participants were drawn from 18 care settings (six primary care or general practice settings, three community health services, four hospices and five departments in three general hospitals).

Data generation

We used focus groups rather than one-to-one interviews to seek insights into attitudes, opinions and underlying assumptions that group interaction can enable (Kitzinger, 1995). Invitation with information about the study was sent to potential participants via local service contacts and leads. Professionals willing to participate were selected so that each focus group was either generally homogenous by discipline to promote sharing of experiences, and equality of professional power (13 groups), or multidisciplinary to encourage exploration of views from members of the same care team (five groups).

A pilot focus group was used to develop our interview topic guide with prompts to generate discussion of participants' experiences based on recall of actual patient cases. This explored perceived strengths, concerns and any other issues of relevance to their practice working with patients of differing ethnicity to themselves in cancer care. In all, 18 focus groups (range 5–11 participants) involving 106 respondents were undertaken, mostly in participants' work settings, using recognised methods (Kitzinger, 1995). All respondents gave written informed consent to their participation and completed brief information about themselves, including self-assigned ethnicity. Group discussions lasted between 1.5 and 3 h, and were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim. The characteristics of participants (74 women, 32 men) and their range of experience of working with patients from ethnic ‘minorities’ are shown in Table 1.

Data analysis and validation

We used constant comparison, in which data were collected and analysed concurrently enabling emergent themes and ideas to be incorporated and explored in subsequent interviews, to develop categories (Strauss and Corbin, 1990). The authors, of differing discipline (JB, a research fellow with linguistics background, JK, an academic family physician and CF, a consultant physician in palliative care medicine), each coded data independently, before discussing and agreeing a final interpretation and the presentation of broad categories, developed from coding, as themes in this paper. Organisation of data was assisted by use of the N-Vivo software given the large size of the data set. New data were used and deviant cases (Strauss and Corbin, 1990) sought to assess the integrity of the categories identified, with data generation continuing until no new categories were emerging suggesting saturation (Strauss and Corbin, 1990).

Preliminary findings were fed back and discussed with a group of seven health-care advocates from minority ethnic communities who worked with cancer patients, and an eight-strong multidisciplinary advisory group with health service and academic expertise in cultural diversity. All focus group participants were also sent and invited to comment on a summary of results, and seven attended a further focus group facilitated by JB and JK to discuss and check validity of our interpretation of the data (Bloor, 1997). These processes confirmed and helped further refine analysis.

Results

Caring for patients of differing ethnicity to their own provided positive experiences and opportunities for respondents. Health professionals perceived patients' needs to be generally similar across ethnic groups, whatever their background. However, they encountered a range of challenges, particularly in encounters with a third party interpreting. Professionals found families' mediation of communication with patients, and approach to ownership of information about their relatives, could make achieving appropriate assessment, informed consent and discussion of care with patients more difficult. This also magnified dilemmas for health professionals about disclosure of cancer diagnosis and prognosis, especially when poor. Professionals' concern to be patient-centred and their regard for patient autonomy were tested in these circumstances.

Opportunities from working with ethnically diverse patients

Respondents gave examples of how they found caring for patients of differing ethnicity to their own to be positive, stimulating and rewarding. These were reflected in aspects of their therapeutic relationship, facilitating patient access to services, developing communication skills and realising opportunities for personal and professional development. For example:

I feel that (having more ethnic minority patients) stimulated personally a learning need in me that I didn't quite appreciate I had and I always thought I'd never get round to doing anything about it (General Practitioner).

Compromise of communication

Participants spoke of a range of constraints on communication with patients where language was not shared or English speaking was limited. Communication often remained unsatisfactory where others acted as interpreter. Professionals identified how establishing concerns, assessing needs, checking understanding or negotiating treatment were more challenging when interactions involved patients with little or no English, with potentially negative consequences for patient care (Box 1). In addition to language, gauging non-verbal communication and cultural differences in expression and perception were further sources of difficulty, even where English was spoken by both parties, leading to misunderstandings (Box 1).

Communication with patients facilitated by trained interpreters, bilingual link workers or advocates was familiar to some respondents. However, experience of family members interpreting for patients was much more common. Here, participants highlighted concerns that information may be filtered or inaccurately translated with consequences not only for the patient, but also with the further potential for conflict between the family member interpreting and the health professional (Box 2).

Some participants found that relatives were not willing to have a professional interpreter present. Determining the patient's wishes for an interpreter in this situation was problematic. Other respondents underlined further concern about the appropriateness of the age or gender of family members acting as interpreters, or the possibility of other aspects of family relationships compromising communication in this context (Box 2).

Working with trained bilingual professionals

Participants with experience of working with a trained professional interpreter usually valued the benefit of their support. Some had worked with bilingual link workers and appreciated their assistance not only with communication during encounters, but also outreach and education. However, working with trained interpreters still posed difficulties. This included planning, resource and practical issues such as lacking a supporting budget or need to anticipate patients' language needs and book interpreting services in advance. When an interpreter was available, health professionals sometimes lacked confidence in their skills or were uncertain about their precise role. Respondents identified general concerns about accurate exchange of information, how gender of interpreters in relation to patients might compromise communication and highlighted how difficult it was to explore how patients were feeling (Box 3).

Working with bilingual colleagues also presented respondents with a sense of changes in their power and control during interactions, including cultural variation in gender relationships. However, some professionals noted that they had no formal training in working with interpreters effectively nor understood what appropriate expectations of interpreters might be, including of interpreters' own training (Box 3).

Correspondingly, respondents who were interpreters or link workers emphasised that many health professionals did not know enough about their role, or about how to work effectively with them. Like some other respondents, they identified a critical need for relevant health professional training. For example:

P5: We have to clarify why it takes so long to explain this word…For example there is no Asian word for cervical smear, so you have to explain what smear is. And probably the doctor will think, ‘oh my god, answer yes or no, why is she taking so long?’, then we have to explain to the doctor why…. So there are difficulties, you know, word to word (Bilingual link workers, G10).

Professional interpreters reflected on the further challenges of their own work and its quality. Their involvement in breaking bad news was frequently problematic, for example, when interpreters had not been briefed about the purpose of the consultation or felt unprepared for this demanding role. Sometimes this reflected tensions they experienced between personal roles expected of them by patients and families, including collusion on non-disclosure of information, and their professional roles. For example:

We go there and the doctor will tell us that the patient's got cancer. And it's like, as soon as you hear that word, we think ‘My god, how are we going to tell the patient? … how are they going to take it and how should we pass it on? (Bilingual link workers, G10)

… and then father-in-law coming in…And basically they were saying to lie to him (patient). That, you know, he will live. But professionally we can't do that, can you? Because while you're interpreting, if you're interpreter you interpret what they (other health professionals) say…and you know, it is hard, I know it is hard for them (family) and for us… (Community health centre/interpreters G5).

Challenges for disclosure, patient autonomy and relationship with patient

Participants perceived the care needs of people from ethnic minority communities with cancer to be generally similar to anyone else with cancer. There was, for example, little discussion of the impact of differing religious or health beliefs. However, they found that how needs were identified and negotiated could be more challenging when relatives mediated communication, creating concerns about whether and how information was disclosed to the patient.

Respondents recognised that families of any background may wish to withhold a diagnosis of cancer from the patient because they wanted the patient to maintain some hope and to fight the disease. However among some minority ethnic communities, they perceived that information about their relative could appear to be more a matter for the family rather than the patient alone. This tended to amplify dilemmas about disclosure. Professionals experienced tension between their regard for individual patient autonomy and being patient-centred on the one hand, and some families' approaches to ownership of information and decision making about care on the other (Box 4).

Participants' perceived involvement of the patient's family could make it difficult to locate the voice of the patient. This had consequences for obtaining informed consent and open discussion of treatment options or end of life plans (Box 5). Set against the competing needs and preferences of the family, respondents found a one-to-one relationship between themselves and the patient more difficult to achieve. Nevertheless, some respondents were more open to less familiar shifts in control of care to the family (Box 5).

Discussion

This study highlights health professionals' experience of frustrated communication with patients from cultures different to their own, particularly when third parties are interpreting. This had potentially negative consequences for cancer care. We identify professionals' concerns about achieving appropriate assessment, discussion and informed consent with patients. When patients' families were involved in encounters, our findings suggest how notions of patient-centredness and patient autonomy may be tested.

Methodological considerations

Our participants' perceptions may not be typical of all health professionals or other settings. It was also recognised that they were actively interested in discussing and reflecting on their cross-cultural work. The findings must be interpreted with regard to the study context and sample as described. However, we engaged a broad range of health professionals with varying characteristics, data generation continued to saturation, negative cases were sought (Strauss and Corbin, 1990) and we undertook validation with participants (Bloor, 1997) and other groups. This increases the likely relevance and transferability of findings beyond the immediate study.

Professionals related their experiences in the context of care of cancer, which might have particularly foregrounded issues of communication. However, the reported challenges of communicating through a third party are likely to be similar in other settings. Although findings concerning disclosure and patient choice may be more particular to cancer care, they might be anticipated in care of other serious illness, and at the end of life, such as advanced cardiovascular or renal disease (Murray et al, 2002). The study adds to limited data on health professional experiences of cross-cultural clinical encounters (Murphy and Clark, 1993; Gerrish, 2001), particularly in the context of cancer and other life-limiting illness (Smith et al, 2009; Worth et al, 2009).

Challenges of intercultural communication

The problems of communicating effectively because of language and cultural differences have long been recognised, but largely informally known in health care. Arguably, one reason that training to work with professional interpreters, or to handle family involvement in interpreting, is still not routinely taught or commissioned is because there have been little published data to expose the need (Jones, 2007). The current findings illustrate, from health professional perspectives, how patient care might continue to suffer as a result of poor, often mediated, communication. This may be at critical points in cancer care, such as assessing level of pain, discussing treatment or exploring concerns and feelings. The danger of professionals relying on prior beliefs or stereotypes about patients may be increased when communication is frustrated by differences in language, culture or communication style. This may also include how language is spoken (Roberts et al, 2005). Moreover, patients might seek and secure less information from professionals when relying on an interpreter. Patient diversity in preferences for information are likely to add further complexity, with variation in desire for details about illness or full disclosure (Muthu Kumar et al, 2004).

These factors may all contribute to care based on partial or inaccurate information, particularly within the reality of service time pressures. Although explanations for ethnic disparities in cancer care, and other settings, are likely to be multifactorial, compromise of communication may play a significant part. This may be further compounded by the uncertainty health professionals may experience in responding to ethnic diversity and the disempowerment this may create in their practice. Distracted by cultural difference, professionals may not employ the interpersonal skills they habitually use in exploring their uncertainty and connecting with other patients (Daniels and Swartz, 2007; Kai et al, 2007).

Enhancing communication through a third party

The nature, efficacy and consequences of interpreter-mediated communication in health encounters have received surprisingly little attention (Kaufert and Putsch, 1997; Skelton et al, 2001; Flores, 2005). The ability to speak, read and write English varies considerably between ethnic groups, but interpreting will remain crucial for significant proportions of populations.

Use of a trained professional interpreter rather than a family member, friend or untrained member of staff is recommended as preferable, ethically and to reduce mistranslation, with use of children seen as particularly inappropriate (Flores et al, 2003; Flores, 2005), and with growing recognition of its critical importance in end of life care (Smith et al, 2009). In this study, communication usually relied on the patient's family, suggesting that achieving this in practice can be more problematic. Family involvement might be the only option where interpreting services are unavailable. There may also be patient or family preference for family interpretation, for example, because of concerns about confidentiality, although reports are conflicting (Chamba and Ahmad, 2000) and further research is needed.

Trained interpreters have been routinely underused (Jones, 2007). Some of our respondents lacked familiarity with interpreting roles and processes, or lacked confidence in the accuracy of translation by both trained interpreters and family members. This is supported by evidence of common errors in interpretation (Flores et al, 2003). The UK's Cancer Reform Strategy (Department of Health, 2007), while highlighting the need for effective communication, does not include the skills to communicate with patients where shared language is lacking or its relevance to reducing inequalities in cancer care. This study underlines need to improve and support professionals' understanding of trained interpreters' roles, and ability to access and work with them effectively, including reducing mistranslation (Bischoff et al, 2003; Kai et al, 2006). This will be crucial if the benefits of better provision of physically present and remote telephone access interpreting services in health care are to be realised.

Given the common reality of family members interpreting for patients, guidance for professionals should incorporate how this might be negotiated in practice, recognising its potential limitations. Professionals should be sensitive to individual patient or family preferences and be prepared for how their sense of control in any triadic encounter may alter. Study data highlight a range of practical questions that guidance and training for professionals should address. Examples are shown in Box 6.

Our findings also suggest a need to support bilingual workers in handling complex information, and tasks such as breaking bad news. Other work has highlighted the concern that interpreters might underestimate psychological concerns (Roy et al, 2005). This may be helped by professionals, where possible, briefing interpreters before consultations about their likely content or purpose. Support for professionals might be complemented with methods to empower patients to communicate their concerns and needs, for example, using audiovisual information (Harmsen et al, 2005), whereas models of advocacy may also offer promise.

Testing notions of patient-centredness and autonomy

Providing information when patients vary in how much and when they wish to know, or relatives seeking to avoid disclosure of bad news, are common challenges (Leydon et al, 2000). These were amplified for professionals in their experience of cross-cultural care. Our respondents found establishing their patient's desire for information about their illness, and informed consent for care was more difficult when families' mediation of communication and decision making in relation to a patient intersected.

Our findings highlight two dilemmas for professionals. Firstly, being less able to achieve direct exploration with some patients, professionals felt, and were by definition, less able to be patient-centred in their approach (Stewart, 2001). This poses a formidable challenge where further development of practical guidance on working with a third-party interpreter or family member may help. Nevertheless, the cross-cultural transferability of patient-centredness remains unclear (Skelton et al, 2001).

Secondly, should negotiation with a patient and their family always require acquiescence to ‘Western’ views of truth telling, and ethical frames of respect for individual rights and patient autonomy? (Kaufert and Putsch, 1997). A framework based on social relationships may be equally valid (Surbone, 2006). Empirical evidence is sparse but, as may be reflected in professionals' experience here, some patients may prefer to give control of decision making to family members (Blackhall et al, 1995; Davis, 1996; Kagawa-Singer and Blackhall, 2001). Adopting an alternative ethical perspective, avoiding telling bad news to a patient may be perceived as reducing harm, with harmful information managed by the family.

Professionals should be sensitive to individual variations in perspectives and avoid stereotyping patients and their families, for example, by assuming a patient would or would not want to be told bad news, or have particular styles of coping (Culver et al, 2002) or use of denial (Roy et al, 2005). They should seek, as far as possible, to explore each patient and family's wishes and attitudes to sharing of information and decision making as a generic principle. Discussion of case examples by health professionals may enhance skills in these crucial areas of assessment for cancer care (Kagawa-Singer and Blackhall, 2001; Kai, 2005).

Our findings underline the need for better awareness and understanding of cultural variation concerning concepts such as patient centredness, patient autonomy and how families might approach disclosure and decision making. The extent to which these concepts may be ethnocentric and lack universality deserves wider consideration. Substantive further research exploring these issues from patient, family and professional perspectives, and by empirical observation of relevant interactions, is needed.

This study suggests a range of ways in which cross-cultural communication and thus quality of care may be compromised when third parties are interpreting for patients. Health professionals require much better support and practical guidance to work effectively both with trained interpreters and with the common reality of patients' families interpreting for patients. Recent initiatives such as the National Communication Skills Programme for health professionals in cancer care (www.connected.nhs.uk) and current review of the NHS Cancer Reform Strategy may present opportunities to include relevant training in the UK, with resources to facilitate learning and discussion becoming available (Kai, 2005). Family involvement in mediation of communication and decision making for patients is particularly challenging, testing notions of patient-centredness and patient autonomy. Barriers of language expose need for great sensitivity to individual variations in these concepts to achieve culturally appropriate care. In these contexts, professionals should explore desire for and attitudes to sharing of information and decision making with each patient and family.

References

Ahmed N, Bestall JC, Ahmedzai SH, Payne SA, Clark D, Noble B (2004) Systematic review of the problems and issues of accessing specialist palliative care by patients, carers and health and social care professionals. Palliat Med 18: 525–542

Bach PB, Cramer LD, Warren JL, Begg CB (1999) Racial differences in the treatment of early-stage lung cancer. N Engl J Med 341: 1198–1205

Bernabei R, Gambassi G, Lapane K, Landi F, Gatsonis C, Dunlop R, Lipsitz L, Steel K, Mor V (1998) Management of pain in elderly patients with cancer. SAGE Study Group. Systematic assessment of geriatric drug use via epidemiology. JAMA 279: 1877–1882

Bhopal RS, Rankin J (1996) Cancer in minority ethnic populations: priorities from epidemiological data. Br J Cancer 74: S22–S32

Bischoff A, Perneger TV, Bovier PA, Loutan L, Stalder H (2003) Improving communication between physicians and patients who speak a foreign language. Br J Gen Pract 53: 541–546

Blackhall L, Murphy S, Frank G, Michel V, Azen S (1995) Ethnicity and attitudes toward patient autonomy. JAMA 276: 1652–1656

Bloor M (1997) Techniques of validation in qualitative research: a critical commentary. In Context and Method in Qualitative Research, Miller D, Dingwall R (eds). Sage: London

Chamba R, Ahmad W (2000) Language, communication and information: the needs of parents caring for a severely disabled child. In Ethnicity, Disability and Chronic Illness, Ahmad W (ed), pp 85–102. Open University Press: Buckingham

Culver JL, Arena PL, Antoni MH, Carver CS (2002) Coping and distress among women under treatment for early stage breast cancer: comparing African Americans, Hispanics and non-Hispanic Whites. Psycho-Oncology 11: 495–504

Daniels K, Swartz L (2007) Understanding health care workers' anxieties in a diversifying world. PLoS Med (Public Library of Science) 4: e319

Davey Smith G, Chaturvedi N, Harding S, Nazroo J, Williams R (2000) Ethnic inequalities in health: a review of UK epidemiological evidence. Crit Pub Health 10: 375–408

Davis A (1996) Ethics and ethnicity: end-of-life decisions in four ethnic groups of cancer patients. Med Law 15: 429–432

Department of Health (2007) Cancer Reform Strategy. Department of Health: London

Flores G (2005) The impact of medical interpreter services on the quality of health care: a systematic review. Med Care Res Rev 62: 255–299

Flores G, Laws MB, Mayo SJ, Zuckerman B, Abreu M, Medina L, Hardt EJ (2003) Errors in medical interpretation and their potential clinical consequences in pediatric encounters. Pediatrics 111: 6–14

Gaffin H, Hill D, Penso D (1996) Opening doors: improving access to hospice and specialist palliative care services by members of the black and minority ethnic communities. Commentary on palliative care. Br J Cancer 29: S51–S53

Gerrish K (2001) The nature and effect of communication difficulties arising from interactions between district nurses and South Asian patients and their carers. J Adv Nurs 33: 566–574

Harmsen H, Bernsen R, Meeuwesen L, Thomas S, Dorrenboom G, Pinto D, Bruijnzeels M (2005) The effect of educational intervention on intercultural communication: results of a randomised controlled trial. Br J Gen Pract 55: 343–350

Jones D (2007) Should the NHS curb spending on translation services? BMJ 334: 399

Kagawa-Singer M, Blackhall LJ (2001) Negotiating cross-cultural issues at the end of life: ‘You got to go where he lives’. JAMA 286: 2993–3001

Kai J (ed) (2005) PROCEED: Professionals Responding to Cancer and Ethnic Diversity. Cancer Research UK: London

Kai J, Beavan J, Faull C, Dodson L, Gill P, Beighton A (2007) Professional uncertainty and disempowerment responding to ethnic diversity in health care: a qualitative study. PLoS Med (Public Library of Science) 4: e323

Kai J, Briddon D, Beavan J (2006) Working with interpreters and advocates. In Valuing Diversity: A Resource for Health Professional Training to Respond to Cultural Diversity, Kai J (ed) 2nd edn, pp 201–224. Royal College of General Practitioners: London

Karim K, Bailey M, Tunna K (2000) Nonwhite ethnicity and the provision of specialist palliative care services: factors affecting doctors' referral patterns. Palliat Med 14: 471–478

Kaufert JM, Putsch RW (1997) Communication through interpreters in healthcare: ethical dilemmas arising from differences in class, culture, language, and power. J Clin Ethics 8: 71–87

Kitzinger J (1995) Qualitative research: introducing focus groups. BMJ 311: 299–302

Koffman J, Burke G, Dias A, Raval B, Byrne J, Gonzales J, Daniels C (2007) Demographic factors and awareness of palliative care and related services. Palliat Med 21: 145–153

Leydon GM, Boulton M, Moynihan C, Jones A, Mossman J, Boudioni M, McPherson K (2000) Cancer patients' information needs and information seeking behaviour: in depth interview study. BMJ 320: 909–913

McMahon Jr LF, Wolfe RA, Huang S, Tedeschi P, Manning Jr W, Edlund MJ (1999) Racial and gender variation in use of diagnostic colonic procedures in the Michigan Medicare population. Med Care 37: 712–717

Murphy K, Clark JM (1993) Nurses' experiences of caring for ethnic-minority clients. J Adv Nurs 18: 442–450

Murray SA, Boyd K, Kendall M, Worth A, Benton TF, Clausen H (2002) Dying of lung cancer or cardiac failure: prospective qualitative interview study of patients and their carers in the community. BMJ 325: 929–932

Muthu Kumar D, Symonds RP, Sundar S, Ibrahim K, Savelyich BSP, Miller E (2004) Information needs of Asian and White British cancer patients and their families in Leicestershire: a cross-sectional survey. Br J Cancer 90: 1474–1478

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) (2004) NICE Cancer Service Guidance on Supportive and Palliative Care. NICE: London

Roberts C, Moss B, Wass V, Sarangi S, Jones R (2005) Misunderstandings: a qualitative study of primary care consultations in multilingual settings, and educational implications. Med Educ 39: 465–475

Roy R, Symonds RP, Kumar DM, Ibrahim K, Mitchell A, Fallowfield L (2005) The use of denial in an ethnically diverse British cancer population: a cross-sectional study. Br J Cancer 92: 1393–1397

Selby P (1996) Cancer clinical outcomes for minority ethnic groups. Br J Cancer 29: S54–S60

Skelton JR, Kai J, Loudon RF (2001) Cross-cultural communication in medicine: questions for educators. Med Educ 35: 257–261

Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR (2003) Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Institute of Medicine: Washington, DC

Smith A, Sudore R, Perez-Stable E (2009) Palliative care for Latino patients and their families: ‘whenever we prayed, she wept’. JAMA 301 (10): 1047–1057, E1

Stewart M (2001) Towards a global definition of patient centred care. BMJ 322: 444–445

Strauss A, Corbin J (1990) Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. Sage Publications Inc.: Newbury Park, CA

Surbone A (2006) Telling the truth to patients with cancer: what is the truth? Lancet Oncol 7: 944–950

Ward E, Jemal A, Cokkinides V, Singh G, Cardinez C, Ghafoor A, Thun M (2004) Cancer disparities by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status. CA Cancer J Clin 54: 78–93

Wild SH, Fischbacher CM, Brock A, Griffiths C, Bhopal R (2006) Mortality from all cancers and lung, colorectal, breast and prostate cancer by country of birth in England and Wales, 2001–2003. Br J Cancer 94: 1079–1085

Worth A, Irshad T, Bhopal R, Brown D, Lawton J, Grant E, Murray S, Kendall M, Adam J, Gardee R, Sheikh A (2009) Vulnerability and access to care for South Asian Sikh and Muslim with life limiting illness in Scotland: prospective qualitative study. BMJ 338: b183

Acknowledgements

We thank study participants; Angela Beighton for assisting with data analysis; Lynn Dodson, Hilda Parker, Paramjit Gill, community and study advisory group members for project support and help with recruitment; Linda Hudson for clerical support; and Jean King, Charlotte Moore and Lesley Walker of Cancer Research UK for their support throughout this project. This work was supported by Cancer Research UK, and ethically approved by Lothian Multi-Centre Research Ethics Committee.

Author Contributions

JB led data generation and, with CF, facilitated recruitment, contributed to data analysis and critically drafting the paper. JK was principal investigator, designed the study, facilitated recruitment, contributed to data generation and analysis, and led writing of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Kai, J., Beavan, J. & Faull, C. Challenges of mediated communication, disclosure and patient autonomy in cross-cultural cancer care. Br J Cancer 105, 918–924 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2011.318

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2011.318

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Factors influencing terminal cancer patients’ autonomous DNR decision: a longitudinal statutory document and clinical database study

BMC Palliative Care (2022)

-

Linguistic barriers in communication between oncologists and cancer patients with migration background in Germany: an explorative analysis based on the perspective of the oncologists from the mixed-methods study POM

Research in Health Services & Regions (2022)

-

Palliative Care Utilization Among Non-Western Migrants in Europe: A Systematic Review

Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health (2022)

-

Exploring access to end of life care for ethnic minorities with end stage kidney disease through recruitment in action research

BMC Palliative Care (2016)

-

Uterine leiomyoma: understanding the impact of symptoms on womens’ lives

Reproductive Health (2014)