Abstract

Water scarcity represents one of the most serious global problems of our time and challenges the advancements in desalination techniques. Although water-filtering architectures based on graphene have greatly advanced the approach to high performance desalination membranes, the controlled-generation of nanopores with particular diameter is tricky and has stunted its wide applications. Here, through molecular dynamic simulations and first-principles calculations, we propose that the recently reported graphene-like carbon nitride (g-C2N) monolayer can serve as high efficient filters for water desalination. Taking the advantages of the intrisic nanoporous structure and excellent mechanical properties of g-C2N, high water transparency and strong salt filtering capability have been demonstrated in our simulations. More importantly, the “open” and “closed” states of the g-C2N filter can be precisely regulated by tensile strain. It is found that the water permeability of g-C2N is significantly higher than that reported for graphene filters by almost one order of magnitude. In the light of the abundant family of graphene-like carbon nitride monolayered materials, our results thus offer a promising approach to the design of high efficient filteration architectures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Because of the surging growth of population, rapid urban development and industrialization progress, the augmentation in available freshwater resources is dwindling in many water-stressed countries of the world1. Seawater represents a plentiful resource to compensate the stress of potable water supply through desalination. As one representative desalination methods, reverse osmosis (RO) technique has been commonly adopted2. In this strategy, a semi-permeable membrane is placed at the interface between seawater and pure water. Pressure applied at the seawater side forces water flow towards the pure water side, while ions are blocked. The pure water production rate of the RO method is typically low, which is ~0.1 Lcm−2day−1MPa−1 for commercially used RO membranes3,4. The sustainability of water resource through desalination, therefore, highly depends on the development of new desalination membranes.

A promising approach is graphene filter which is first proposed from computer simulations3,4,5,6 and eventually realized in recent experiments7,8. Thanks to the ultrathin thickness (only one atomic layer) of graphene, the energy consumption in seawater desalination is greatly reduced because water flux scales inversely with the filter thickness. This approach may also works for other two-dimensional (2D) materials, such as such as hexagonal boron nitride9, silicene10,11, phosphorene12,13,14,15 and molybdenum disulfide (MoS2)16. Recently, the MoS2-based filter was reported to have high performance given that nanopores are introduced to the MoS2 monolayer through bombardment or chemical treatment17,18. However, to be used as filtering membranes, these materials face the same limitation: they do not have inherent nanopores for water flow and thus post-treatment is essential. The shape and size of the nanopores generated during nanoengineering process are decisive factors for water transparency and ion selectivity. However, the successful experimental realization of proper nanopores still remains challenging at present, which becomes to be a major obstacle to the design of advanced filteration architectures based on these 2D materials.

It is noteworthy that there are various types of graphinic carbon nitrides with inherent nanopores in different shapes, which are potential filteration material candidates19,20,21,22,23,24. In particular, the nanopores in the recently-synthesized graphene-like carbon nitride25 (referred to as g-C2N, as shown in Fig. 1) has diameter of ~4.1 Å (determined by the N atoms and minus the diameter of a N, ~1.5 Å); the size is very close to that of the water molecule (~4 Å). The C-C and C-N covalent bond-based framework result in excellent mechanical properties of the g-C2N which is almost comparable to graphene. The stability of g-C2N monolayer at high temperature has also been demonstrated experimentally25. Thus, the intrisic porous structure implies high prospect of using porous g-C2N monolayer as desalination filter without post-treatment to generate nanopores.

In this work, we report the seawater desalination performance of the g-C2N membrane through molecular dynamics (MD) simulations and first-principles calculations. It is found that tensile strain can effectively modulate the permeation of water through the g-C2N filter continuously from “closed” to “open” states. The water permeability is about two orders of magnitude higher than the commercial RO membranes, while ion transmission is totally blocked. The high water transparency and vigorous salt filtering capability are attributed to the steric hindrance and electrostatic interactions on the translocations of water molecules and ions through nanoscaled confinements. Our results thus highlight the significance of a new 2D material family for high performance seawater desalination filters.

Methods

MD simulations

As illustrated in Fig. 1a, the MD simulation model is composed of a seawater region and a pure water region, separated by a g-C2N filter. A graphene sheet mimicing the piston is placed on the top of the seawater and force is loaded on it (at 20, 40, 60, 80 and 100 MPa pressure equivalents) in the z direction to push water flow towards the pure water region. The g-C2N filter (Fig. 1b) containing 30 nanopores has a dimension of roughly 4.16 × 4.33 nm2 at the strain-free state. The structure of nanopore is illustrated in Fig. 1c, for which the framework is composed of sp2 hybridized C and pore edges are terminated by N atoms. Strain on the g-C2N filter is modulated by increasing and fixing the size of the cross sectional area.

All the simulations were performed with the GROMACS package26. The AMBER03 force field27 was used in the simulations. The seawater region contains 50 Na+ and Cl− ions and 7000 TIP3P water molecules28, corresponding to a salt concentration of 27 g L−1, slightly lower than the salinity of seawater (~35 g L−1). A lower salinity was chosen for the consideration that water flowing towards the pure water region will effectively increase the salinity in seawater side during the simulation. For the g-C2N filter, the atom types of CA and NB were assigned to C and N atoms. The RESP point charges were calculated using the Gaussian 09 code29 at the HF/6–31G* level, yielding a value of 0.24 |e| and −0.48 |e| for C and N atoms, respectively. SHAKE constraints30 were applied to all bonds involving hydrogen atoms. The long-range electrostatic interactions were treated with the Particle Mesh Ewald method31,32 and atypical distance cutoff of 12 Å was adopted for the van der Waals (vdW) interactions. The non-bonded interaction pair list was updated every 10 fs. The cross section in the x-y plane of the simulation box was fixed to a certain value in order to mimic the strained filter. The box was coupled to a constant at 1.0 atm only along the z direction. Canonical sampling was performed through velocity rescaling method at constant temperature 300 K33. A movement integration step of 1 fs was used in the simulations. Each system was first equilibrated for 10 ns, followed by 300 ns productive simulation for the data collection.

First-principles calculations

First-principles calculations were further performed to check the structure stability using the Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP)34,35,36,37. The electron-electron interactions are treated using a generalized gradient approximation (GGA) in the form of Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) for the exchange-correlation functional38. The energy cutoff of the plane waves was set to 520 eV with an energy precision of 10−8 eV. Vacuum space larger than 15 Å was used to avoid the interaction between adjacent images. The Monkhorst-Pack meshes of 9 × 9 × 1 were used in sampling the Brillouin zone for the g-C2N lattice. Tensile strain was applied by fixing the lattice constants to different values. Atomic coordinates were optimized using the conjugate gradient (CG) scheme until the maximum force on each atom was less than 0.01 eVÅ−1. Phonon spectra were calculated using a supercell approach within the PHONON code39.

Results and Discussion

Structural stability of g-C2N membrane

The structural stability of g-C2N membrane under tensile strain is an important issue. The strain energy (Es) of g-C2N under tensile strain (τ) was firstly calculated using first-principles calculations. As shown in Fig. 2a, with the increase of tensile strain, Es increases monotonously as τ < 20%. However, it is found that the derivate of strain energy (dEs/dτ) reaches the maximum at tensile strain of around 13%, suggesting that the g-C2N lattice becomes softer beyond this point. This is futrher confirmed by the features of phonon spectra. When the tensile strain is smaller than 12%, the phonon spectra are free from imaginary frequency modes (Fig. 2b), which indicates the stability of the filter at this critical point. When the tensile strain exceeds 12%, imaginary frequency branch appears as demonstrated in Fig. 2c, which reveals the fact that the g-C2N lattice becomes unstable, as external disturbance may destroy the g-C2N framework due to the imaginary frequency mode. Both the energy evolution and phonon spectra confirm that the g-C2N has excellent mechanical stability which can bear tensile strain of up to 12%. The high structural stability of the g-C2N sheets fulfills the requirement of filters working at high pressure.

Water permeability performance

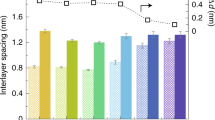

We first tested the water transparency of the g-C2N filter under the pressure of 100 MPa. The cumulative numbers of water molecules transferred through the g-C2N filter are summarized in Fig. 3a. For g-C2N filter at the equilibrium state (without tensile strain) and under weakly strained (τ ≤ 1%) conditions, no event of water passage is observed during the entire simulations, indicating that the filter is at “closed” state. The transition point from “closed” to “open” appears at a strain level near 2%, for which 16 water molecules were found to pass through the filter during the 300 ns simulation. As the strain is further increased, the g-C2N filter becomes more transparent. For τ ≥ 6%, each curve in Fig. 3a begins with a linear region and eventually reaches a saturation point (around 6500 water molecules) where the entire reservoir of water molecules on the seawater region is completely depleted. This indicates that tensile strain can effectively modulate the permeation of water through the g-C2N filter.

(a) Number of water filtered by g-C2N membrane as a function of simulation time under piston pressure of 100 MPa, (b) Water flow at various pressure through the 12%-stretched g-C2N, (c) Pore diameter and water permeability with respect to tensile strain and (d) Water permeability with respect to the charges of nitrogen of the g-C2N filter under tensile strain of 6% and 11%.

Notably, for all the simulations at different tensile strain, the water flow (the slope of curves in Fig. 3a) is constant in time, confirming that well-converged statistics is obtained for all the simulations. The water flow with respect to external pressure for the 12%-strained filter is summarized in Fig. 3b. It is seen that the water flow is proportional to the strength of applied pressure. This allows us to evaluate the water permeability of g-C2N filter by extrapolating the dynamic quantities derived here down to the operating condition that is more typical of RO plants (usually several MPa). We expressed the water permeability in liters of output per square centimeter of the filter per day and per unit of applied pressure. As shown in Fig. 3c, it varies from zero (for the unstrained g-C2N) to 35.1 Lcm−2day−1MPa−1 (for the extremely strained case). The high performance benefits from the densely packed nanopores in g-C2N filter (with density of 1.6 × 1014 cm−2). For comparison, the highest performance that has been achieved for graphene filter is around 6 Lcm−2day−1MPa−1 which is only 1/6 of that of g-C2N filter reported here7. It is also noteworthy that the performance of commercial RO is only in the order of 0.1 Lcm−2day−1MPa−1 5,40. This solidly highlights the importance of the unique porous structure of g-C2N as a filter material. More interestingly, there exists a strain window (6–11%) where the water permeability scales almost linearly with strain strength. This property allows a precise control of the g-C2N filter which is quite crucial for the design of tunable devices for filtration and other applications.

As illustrated in Fig. 3c, for the 6%-strained filter, the diamater of the permeable pores reaches 4.6 Å, compared to a value of 4.1 Å for strain-free g-C2N. For even larger strain, the pore diameter increases almost linearly with respect to the strain strength. The tunable water permeation through the g-C2N filter is mainly attributed to the expanded nanopores upon stretching which effectively decrease the steric confinement effect for water passage.

For graphene based filter, it has been evidenced that the edge morphology of the nanopores, especially the hydrophobicity, would significantly regulate the water flow5. In view that stretching of chemical bonds may cause slight electron re-distribution between adjacent elements, we examined the effect from atomic charges of the g-C2N filter on the water flux. For N, we have considered values from 0.4 to 0.6 |e| in our simulations (the atomic charge of C was changed accordingly). The water permeabilities under tensile strain of 6% and 11% are summarized in Fig. 3d. It is clear that the nanopores with less-charged edge atoms have larger water permeability. On the contrary, accumulation of electrons at the nanopores will decrease the water permeability. In general, the change of water permeability in response to the N charge is only 1.0 Lcm−2day−1MPa−1 per 0.1 |e|, which is much lower than the strain effect. Therefore, it is safe to propose that the regulation of the water flux by strain is mainly determined by the changes of steric hindrance upon modulations of the nanopore size.

Salt rejection performance

The desalination efficiency is determined by the trade-off between water permeability and salt ion selectivity. Beside high water permeability, a desalination filter should effectively hinder the passage of salt ions. For graphene, the nanopores generated during pre-treatment always have a broad range of diameter, resulting in lower salt rejection performance. For the g-C2N, it is exciting that no events of ion passage through the filter have been observed throughout all the simulations with serious of strain and pressure. It is worth noticing that during the simulation, the effective salinity in seawater region keeps increasing because the piston pressure depletes the water molecules in seawater side. This indicates that the salt rejection performance of g-C2N filter is robust, which is quite crucial for desalination performance improvement. This should be attributed to the considerable small size of the nanopores, which can efficiently block the ion transmission, corresponding to the maximal water desalination efficiency.

Free energy profiling analysis

The physical origins of the high performance of g-C2N filter can be explained by the potential of mean force (PMF) analysis through umbrella sampling. The PMF curves for Na+, Cl− and water to across the g-C2N filter were obtained by sampling the force experienced by the salt ions or water molecules when passing through the nanopores. Without losing the validity, we have only calculated the PMF curves for the 12%-strained filter. As shown in Fig. 4, the PMF for water molecules is most shallow, with no energy barrier (peak) exceeding 3.32 kBT. Typically, an energy barrier of around 5 kBT is considered to be low enough for water permeation to happen41,42,43. Hence water molecules can pass through the nanopores easily, leading to high water transparency. Na+ is blocked because of the high energy barrier of 12.27 kBT near the nanopore center. The probability (Kr) for certain solution component to overcome an energy barrier (Eb), Kr ∝ exp((−Eb)/kBT), indicates that the water molecules have approximately 8 × 103 times higher chance to pass through the nanopores compared to Na+ ions at room temperature. For Cl− to approach the nanopores from the seawater side, an energy barrier of larger than 35 kBT is predicted which is almost inaccessible for transmission to happen.

In experiments, there are several approaches available for applying tensile strain to the 2D monolayer. For instance, g-C2N membrane can be deposited on flexible substrate like polymethyl methacrylate. Strain can be directly applied on the substrate to induce deformation of the substrate and accordingly the stretching of the g-C2N. Such approach has been adopted for the tuning of electronic structure of MoS2 monolayer by strain44. Other than direct mechanical stretching, novel substrates which have large thermal expansion coefficient would also serve as the necessary support and introduce strain on the g-C2N filter45.

Conclusions

In summary, through molecular dynamics simulations we demonstrate that the recently reported g-C2N monolayer can serve as an efficient filter material for seawater desalination. Under tensile strain, the inherent nanopores of g-C2N sheets can conduct water in a high transparency manner, while salt ions are completely rejected. The high water transparency and vigorous salt filtering capability are attributed to the steric hindrance and electrostatic interactions on the translocations of water molecules and ions through nanoscaled confinements. The highest water permeability is about two orders of magnitude higher than the commercially-used RO membranes and six times higher than that reported for graphene-based filters. More importantly, the “open” and “closed” states for water flow can be accurately regulated by applying tensile strain. The advantage of the g-C2N filter over graphene filter is the inherent porous framework with permeable pores. The easy regulation of the filter with tensile strain and the precise pressure responsive behavior make the g-C2N on the horizon to advance the development of desalination filter. Our results also support the design and proliferation of tunable devices for filtration and other applications working at nanoscale.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Yang, Y. et al. Tunable C2N Membrane for High Efficient Water Desalination. Sci. Rep. 6, 29218; doi: 10.1038/srep29218 (2016).

References

Elimelech, M. & Phillip, W. A. The future of seawater desalination: energy, technology and the environment. Science 333, 712–717 (2011).

Sidney, L. & Srinivasa, S. In Saline Water Conversion - II Vol. 38 Advances in Chemistry Ch. 9, 117–132 (American Chemical Society, 1963).

Sint, K., Wang, B. & Král, P. Selective ion passage through functionalized graphene nanopores. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 16448–16449 (2008).

Suk, M. E. & Aluru, N. Water transport through ultrathin graphene. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 1, 1590–1594 (2010).

Cohen-Tanugi, D. & Grossman, J. C. Water desalination across nanoporous graphene. Nano Lett. 12, 3602–3608 (2012).

Sun, C. et al. Mechanisms of molecular permeation through nanoporous graphene membranes. Langmuir 30, 675–682 (2014).

Surwade, S. P. et al. Water desalination using nanoporous single-layer graphene. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 459–464 (2015).

O’Hern, S. C. et al. Selective ionic transport through tunable subnanometer pores in single-layer graphene membranes. Nano Lett. 14, 1234–1241 (2014).

Watanabe, K., Taniguchi, T. & Kanda, H. Direct-bandgap properties and evidence for ultraviolet lasing of hexagonal boron nitride single crystal. Nat. Mater. 3, 404–409 (2004).

Lalmi, B. et al. Epitaxial growth of a silicene sheet. Appl. Phys. Lett. 97, 223109 (2010).

Vogt, P. et al. Silicene: compelling experimental evidence for graphenelike two-dimensional silicon. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 155501 (2012).

Liu, H. et al. Phosphorene: an unexplored 2D semiconductor with a high hole mobility. ACS Nano 8, 4033–4041 (2014).

Reich, E. S. Phosphorene excites materials scientists. Nature 506, 19–19 (2014).

Li, W., Zhang, G. & Zhang, Y.-W. Electronic properties of edge-hydrogenated phosphorene nanoribbons: a first-principles study. J. Phys. Chem. C 118, 22368–22372 (2014).

Li, W., Yang, Y., Zhang, G. & Zhang, Y.-W. Ultrafast and directional diffusion of lithium in phosphorene for high-performance lithium-ion battery. Nano Lett. 15, 1691–1697 (2015).

Coleman, J. N. et al. Two-dimensional nanosheets produced by liquid exfoliation of layered materials. Science 331, 568–571 (2011).

Li, W., Yang, Y., Weber, J. K., Zhang, G. & Zhou, R. Tunable, strain-controlled nanoporous MoS2 filter for water desalination. ACS Nano 10, 1829–1835 (2016).

Heiranian, M., Farimani, A. B. & Aluru, N. R. Water desalination with a single-layer MoS2 nanopore. Nat. Commun. 6 (2015).

Wang, A. & Zhao, M. Intrinsic half-metallicity in fractal carbon nitride honeycomb lattices. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 17, 21837–21844 (2015).

Zhang, X. & Zhao, M. Prediction of quantum anomalous Hall effect on graphene nanomesh. RSC Adv. 5, 9875–9880 (2015).

Zhang, X., Wang, A. & Zhao, M. Spin-gapless semiconducting graphitic carbon nitrides: A theoretical design from first principles. Carbon 84, 1–8 (2015).

Li, H. et al. Tensile strain induced half-metallicity in graphene-like carbon nitride. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 17, 6028–6035 (2015).

Wang, A., Zhang, X. & Zhao, M. Topological insulator states in a honeycomb lattice of s-triazines. Nanoscale 6, 11157–11162 (2014).

Li, F., Qu, Y. & Zhao, M. Efficient helium separation of graphitic carbon nitride membrane. Carbon 95, 51–57 (2015).

Mahmood, J. et al. Nitrogenated holey two-dimensional structures. Nat. Commun. 6 (2015).

David Van Der, S. et al. GROMACS: Fast, flexible and free. J. Comput. Chem. 26, 1701–1718 (2005).

Duan, Y. et al. A point-charge force field for molecular mechanics simulations of proteins based on condensed-phase quantum mechanical calculations. J. Comput. Chem. 24, 1999–2012 (2003).

Jorgensen, W. L., Chandrasekhar, J., Madura, J. D., Impey, R. W. & Klein, M. L. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 79, 926–935 (1983).

Frisch, M. et al. Gaussian 09, Revision A. 02, Gaussian. Inc., Wallingford, CT200 (2009).

Ryckaert, J. P., Ciccotti, G. & Berendsen, H. J. C. Numerical integration of the cartesian equations of motion of a system with constraints: molecular dynamics of n-alkanes. J. Comput. Phys. 23, 327–341 (1977).

Essmann, U. et al. A smooth particle mesh Ewald method. J. Chem. Phys. 103, 8577–8593 (1995).

Darden, T., Perera, L., Li, L. & Pedersen, L. New tricks for modelers from the crystallography toolkit: the particle mesh Ewald algorithm and its use in nucleic acid simulations. Structure 7, R55–R60 (1999).

Bussi, G., Donadio, D. & Parrinello, M. Canonical sampling through velocity rescaling. J. Chem. Phys. 126, 014101 (2007).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for open-shell transition metals. Phys. Rev. B 48, 13115–13118 (1993).

Kresse, G. & Furthmuller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmuller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Parlinski, K., Li, Z. Q. & Kawazoe, Y. First-principles determination of the soft mode in cubic ZrO2 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 78, 4063–4066 (1997).

Pendergast, M. M. & Hoek, E. M. V. A review of water treatment membrane nanotechnologies. Energ Environ. Sci. 4, 1946–1971 (2011).

de Groot, B. L. & Grubmüller, H. The dynamics and energetics of water permeation and proton exclusion in aquaporins. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 15, 176–183 (2005).

Borgnia, M. J. & Agre, P. Reconstitution and functional comparison of purified GlpF and AqpZ, the glycerol and water channels from Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 98, 2888–2893 (2001).

Won, C. Y. & Aluru, N. Water permeation through a subnanometer boron nitride nanotube. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 2748–2749 (2007).

He, K., Poole, C., Mak, K. F. & Shan, J. Experimental demonstration of continuous electronic structure tuning via strain in atomically thin MoS2. Nano Lett. 13, 2931–2936 (2013).

Plechinger, G. et al. Control of biaxial strain in single-layer molybdenite using local thermal expansion of the substrate. 2D Mater. 2, 015006 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Basic Research Program of China (No. 2012CB932302), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos 11304214, 21405108 and 21433006). A Project Funded by the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PAPD) and Jiangsu Provincial Key Laboratory of Radiation Medicine and Protection.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Y., W.L., H.Z. and X.Z. carried out the simulations and analysis; W.L. and M.Z. initiated the idea and checked the results. All the authors wrote and reviewed the manuscript text.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, Y., Li, W., Zhou, H. et al. Tunable C2N Membrane for High Efficient Water Desalination. Sci Rep 6, 29218 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep29218

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep29218

This article is cited by

-

A simple and efficient process for the synthesis of 2D carbon nitrides and related materials

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Towards the realisation of high permi-selective MoS2 membrane for water desalination

npj Clean Water (2023)

-

Water desalination across functionalized silicon carbide nanosheet membranes: insights from molecular simulations

Structural Chemistry (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.