Abstract

Using data from families in which marker genotypes are known for the father, the mother and the affected offspring, a simple statistic for testing for imprinting effects is developed. The statistic considers whether the expected number of families in which the father carries more copies of a particular marker allele than the mother is equal to the expected number of families in which the mother carries more copies of the allele than the father. The proposed parent-of-origin effects test statistic (POET) is shown to be normally distributed and can be employed to test for imprinting in situations where the marker locus need not be a disease susceptibility locus and where the female and male recombination fractions are sex-specific. A simulation study is conducted to characterize the power of the POET and other properties, and its results show that it is appropriate to employ the POET.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Genomic imprinting, also known as ‘parent-of-origin’ effects, exists in many mammalian genes. Imprinting has been illustrated in several genetic disorders such as Beckwith–Wiedemann, Prader–Willi and Angleman syndromes (Falls et al., 1999). Morison et al. (2001) have constructed an imprinted-gene database, which contained more than 230 records at the time of submission (http://igc.otago.ac.nz). Reviews of the mechanisms and function of genomic imprinting have been conducted by Pfeifer (2000), Reik and Walter (2001) and Wilkins and Haig (2003).

As the usual statistical methods for linkage analysis may be ineffective or fail to detect linkage for an imprinted gene, several studies have been performed recently to test for imprinting for qualitative and quantitative traits or to incorporate imprinting effects into existing tests for linkage. Based on case–parents trios, Weinberg (1999) proposed some test statistics to test for imprinting and maternal effects when a marker locus is a disease susceptibility locus (DSL). A likelihood-based method, allowing for incorporation of ascertainment and differential male and female ascertainment probabilities, has been developed for testing for imprinting effects in complex diseases (Haghighi and Hodge, 2002). For the affected sib pairs analysis, Wu et al. (2005) have proposed a robust generalized minimax test for imprinting and linkage, based on alleles shared identity-by-descent for the incorporation of imprinting effects. For the quantitative trait locus, mixture models have been used to perform quantitative tests for maternal effects and imprinting effects with incomplete case–parents trios (Van den Oord, 2000). Hanson et al. (2001) and Shete and Amos (2002) have used the statistics constructed for linkage between the trait and the marker locus in the variance-components (Amos, 1994) and Haseman and Elston (1972) models, respectively, to test whether the effect of the maternally derived locus is equal to that of the paternally derived locus with sex-specific recombination fractions. Shete et al. (2003) have extended the variance-components model to test for imprinting by using extended pedigrees.

Human recombination fraction can differ between males and females. Feenstra et al. (2004) used the lod scores to detect sex differences in male–female recombination fractions. The recombination rate for human females is on average 60% higher than that for human males (Fann and Ott, 1995; Broman et al., 1998; Ott, 1999; Feenstra et al., 2004). In linkage analysis, sex-specific recombination rates will be a consequence of imprinting, and Smalley (1993) suggested that this information could be used to try to identify the traits undergoing imprinting. Hence, it is particularly important in testing for imprinting and conducting linkage analysis with imprinting effects to incorporate the sex-specific recombination fractions into the analysis.

The paper is organized as follows. Based on the case–parents trios, the same data used in the transmission disequilibrium test (TDT) for linkage (Spielman et al., 1993), we first propose a novel parent-of-origin effects test (POET) to test for imprinting in situations where the marker locus need not be a DSL per se and where the female and male recombination fractions are sex-specific. The POET tests the equality of the expected numbers of two groups of families that are in symmetry in terms of the mating type. The test statistic is shown to be asymptotically normal distributed. We then compare the type I error rates of the test statistic simulated by 10 000 replicates with the nominal level of 0.05 for a variety of parameter values, and find that they are highly consistent. The analytical power is derived and is compared with the power obtained by simulation. They are found to be almost the same. The simulation results illustrate that it is appropriate to use the POET.

Methods

Notations and data

Assume that at the marker locus there are two alleles M1 and M2 with population frequencies g and g′=1−g, respectively. Note that M1 and M2 may represent two groups of alleles. It is convenient to denote the marker genotypes M2M2, M1M2, and M1M1 by the numbers 0, 1, and 2, respectively (i.e. the number of copies of the marker allele M1 carried by an individual). At a DSL, there are two alleles D and d with population frequencies p and q=1−p, respectively. In order to take imprinting effects into account, it is necessary, for a heterozygote Dd, to specify the parental origin of the disease allele D. We therefore let D/D, D/d, d/D and d/d denote the four ordered genotypes at the DSL, where the left allele of the slash / is paternal and the right allele is maternal. We assume that there is no maternal effect (e.g. intrauterine effect, mitochondrial effect), so the risks for an individual with two copies, one paternal copy, one maternal copy, and no copies of the disease allele D at the DSL are denoted by φD/D, φD/d, φd/D and φd/d, respectively. The population disease prevalence is then φ=p2φD/D+pqφD/d+pqφd/D+q2φd/d. Without loss of generality, we assume that the risk for an individual with two copies of the disease allele D is greater than for an individual with one copy, either paternal or maternal, and similarly that the risk for an individual with one copy is greater than for one with no copies. φD/d=φd/d indicates that the paternally derived allele is completely silenced and φd/D=φd/d indicates that the maternally derived allele is completely silenced. The condition φD/d=φd/D holds if and only if there is no imprinting effect. φD/d>φd/D indicates that a paternally derived allele is associated with a greater increase in risk than a maternally derived allele. Similarly, φd/D>φD/d indicates that a maternally derived allele is associated with a greater increase in risk than a paternally derived allele. Imprinting effects can be measured by the degree of imprinting I=(φD/d−φd/D)/2 (Strauch et al., 2000), the half of the difference between the expression of the paternally derived allele and that of the maternally derived allele, which is the negative value of the ‘delta’ measure (Haghighi and Hodge, 2002). It follows that (φd/d−φD/D)/2⩽I⩽(φD/D−φd/d)/2. Note that here we allow genes to be partially imprinted, although genes are believed to be either completely imprinted or not at all. The case of I=(φd/d−φD/D)/2 corresponds to complete paternal imprinting or complete maternal expression and the case of I=(φD/D−φd/d)/2 corresponds to complete maternal imprinting or complete paternal expression. So the null hypothesis of no imprinting effects is equivalently expressed as I=0. The coefficient of linkage disequilibrium (LD) between the marker locus and the DSL is taken as  , where

, where  is the frequency of haplotype DM1. Suppose that the marker locus is in LD with the DSL (i.e. δ≠0). Let θf and θm denote, respectively, the female and male recombination fractions between the marker locus and the DSL.

is the frequency of haplotype DM1. Suppose that the marker locus is in LD with the DSL (i.e. δ≠0). Let θf and θm denote, respectively, the female and male recombination fractions between the marker locus and the DSL.

Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium in the parental generation and Mendelian transmission are assumed throughout this paper. There are n independent case–parents trios, each with known marker genotypes FMC, where F, M and C, respectively, denote the genotypes of the father, mother and affected child at the marker locus. Notice that in each case–parents trio, the child's disease phenotype is known (affected) and the marker genotypes of the trio are known. These families are classified jointly by the mating type FM, the paired parental genotypes and the genotype C of the affected child. The mating symmetry is assumed in the sense that P(F=i, M=j)=P(F=j, M=i) for all i, j=0, 1, 2. There are theoretically 33=27 types of combinations, but only 15 of these types are genetically possible. Let NFMC denote the number of families that fall into genotype category FMC. These 15 numbers {NFMC} follow a multinomial distribution. We are interested in the distribution of such a trio when the trio has been selected because the child is affected. Bayes' theorem is employed to calculate the conditional probability for a trio, given that the child is a case. Table 1 lists all 15 types of family and the corresponding conditional probabilities. Their derivations are outlined in Appendix A. An essential issue is to find out the informative families relevant to genomic imprinting from these 15 types of family.

Proposed statistic and power

In order to effectively exploit the information from trios relevant to imprinting effects, the trios are partitioned into three groups by the mating types FM. The first, second and third groups are characterized by F>M, M>F and F=M respectively (see the third column of Table 1). When the father and the mother carry the same number of copies of the marker allele M1, they have an equal chance of transmitting M1 to the affected offspring. Let NF>M=N100+N101+N201+N211+N212 denote the number of families in the first group and NM>F=N010+N011+N021+N121+N122 the number of families in the second group. If there is no imprinting effect, the difference between the numbers of families belonging to these two groups is expected to be zero by symmetry. Furthermore, NF>M>NM>F would provide a clue of paternal expression of the disease allele D and the reverse case NF>M<NM>F would provide a clue of maternal expression of the disease allele D. In fact, we obtain E(NF>M−NM>F)=2nδ(1−g+g2)I/φ from Table 1 after tedious algebra. So in the presence of LD, the expected numbers of families belonging to the first two groups are equal if and only if there is no imprinting effect (i.e. I=0), based on the fact that 1−g+g2 is greater than 3/4 whatever the g value. So the test for I=0 essentially tests for the equality of E(NF>M) and E(NM>F). Hence, we propose the following ‘parent-of-origin effects test’ (POET) statistic

where NF>M+NM>F is the minimum variance unbiased estimator for the variance of NF>M−NM>F. Notice that the (square of the) POET is a McNemar's test and has a similar form as the TDT (Spielman et al., 1993).

Based on the theorem in Appendix B, we can derive the asymptotic distribution of the POET. This is N(μ,σ2), where

e1 and e2 are the sums of the conditional probabilities of mating types 1 and 2 (see the last column of Table 1), respectively, e1−e2=2δ(1−g+g2)I/φ, e1+e2=2g(1−g)(2−3g+3g2)+2δΔ(1−2 g)(1−3g+3g2)−2Rδ2(1−3g+3g2)/φ, R=φD/D−φD/d−φd/D+φd/d is the difference between the sum of two homozygote risks and the sum of two heterozygote risks and Δ=(p(2φD/D−φD/d−φd/D)+q(φD/d+φd/D−2φd/d))/(2φ) is the difference between two ratios P(D∣affected child)/P(D∣random man) and P(d∣affected child)/P(d∣random man), where P(D∣affected child) represents the probability that a chromosome of an affected child has an allele D at the DSL, and the other three probabilities P(D∣random man), P(d∣affected child) and P(d∣random man) are similarly defined.

It is obvious that under the null hypothesis of no imprinting, we have μ=0 and σ2=1. So the corresponding rejection region about no genomic imprinting is ∣POET∣>zα/2, where α is the significance level and zα/2 is the upper α/2 point of a standard normal distribution. In this paper, the significance level is taken as 0.05 and z0.025=1.96. It follows immediately that the asymptotic power of the POET is

where Φ(·) is the cumulative distribution function of a standard normal random variable. The asymptotic normality of the POET and the accuracy of the power Equation (4) are assessed via simulations.

Remarks

It is obvious from the power expression (4) that there are numerous parameters that affect the power of the POET. Let γ2=φD/D/φd/d, γ1p=φD/d/φd/d, γ1m=φd/D/φd/d denote the genotypic relative risks (Risch and Merikangas, 1996), and γ1=(γ1p+γ1m)/2 denote the average of the two heterozygous genotypic relative risks, then Δ=(pγ2+(q−p)γ1−q)/(p2γ2+2pqγ1+q2), I/φ=(γ1p−γ1m)/(2(p2γ2+2pqγ1+q2)),R/φ=(γ2−2γ1+1)/(p2γ2+2pqγ1+q2). It is concluded from Equation (4) that the power depends on the four risks φD/D, φD/d, φd/D, φd/d only through γ2, γ1p and γ1m. So we fix the background risk φd/d at 0.05 in our simulation study. Notice that γ1p=1 means complete silencing of the paternally derived allele and γ1m=1 means complete silencing of the maternally derived allele.

It is noted that the power of the POET is independent of the designation of the two marker alleles M1 and M2. In fact, if we interchange M1 and M2, the coefficient of LD changes from δ to −δ. So, from the expressions of μ and σ2 in Equations (2) and (3), we find that the mean of the POET changes from μ to −μ while σ2 remains unchanged. Therefore, the power of the POET is invariant when the two marker alleles M1 and M2 are interchanged. As a result, we need only to consider the case where the marker allele frequency g is less than 0.5 in the simulation study.

Notice from Equations (2) and (3) that the analytical power of the POET is symmetric about the degree of imprinting I. Interpreted precisely, for the parameter vector (φD/d, φd/D), the power evaluated at φD/d=a, φd/D=b is just the same as that evaluated at φD/d=b, φd/D=a while all other parameters remain unchanged. In particular, we conclude that the silencing of the paternally derived allele and the complementary silencing of the maternally derived allele are equally easy or equally difficult to detect. We therefore need only to assess the performance of the POET in the case of I>0 in our simulation study.

Simulation methods

In order to assess the performance of the POET in finite samples, a number of parameter values are chosen for the simulation study, based on the following principles. The parameters γ2 and p are chosen as follows: γ2=2, 4, 8, 16 and p=0.01, 0.1, 0.5, 0.8 (Risch and Merikangas, 1996; Knapp, 1999; Deng and Chen, 2001). When γ2 is given, we take γ1=(3+γ2)/4, (1+γ2)/2, (1+3γ2)/4, equally spaced in the range of 1 and γ2. For a given γ1, the range of the degree of imprinting I according to the diamond of inheritance (Strauch et al., 2000) can be derived as follows: when γ1=(3+γ2)/4 or (1+3γ2)/4, φd/d(1−γ2)/4⩽I⩽φd/d(γ2−1)/4; when γ1=(1+γ2)/2, φd/d(1−γ2)/2⩽I⩽φd/d(γ2−1)/2. The coefficient of LD δ is taken as 0.9δmax (Deng and Chen, 2001), where δmax=min(p(1−g), g(1−p)). Remember that the analytical power of the POET is independent of the designation of the two marker alleles. So we choose g=0.2 or 0.4. For illustrative purposes, we adopt θf=0.146 and θm=0.084, which are the female and male recombination fractions between ABO and the locus for the nail–patella syndrome (NPS1) respectively (Ott, 1999). Once the parameter values and the sample size n are chosen, we randomly generate n trios according to the probability distribution listed in the last column of Table 1. For a given number of replicates (e.g. 10 000 replicates), the n trios are generated with 10 000 replicates, and so it follows 10 000 values of the POET. For the given significance level α, the actual power/type I error rate is then estimated as the proportion of rejecting the null hypothesis (i.e. ∣POET∣>zα/2), in 10 000 replicates performed when the alternative/null hypothesis holds.

Results

For a given significance level α=0.05, Table 2 exhibits the actual type I error rates of the POET with 10 000 replicates for a variety of parameter values, where the sample size n=100, g=0.2, θf=0.146 and θm=0.084. The entries in Table 2 show that the actual type I error rates are highly consistent with the nominal value of 0.05, which demonstrates the high accuracy of the asymptotic normality result of the POET under the null hypothesis of no imprinting. We also investigate the performance of the POET when the female and male recombination fractions take other values, when g=0.4, and when the sample size n=200 or 400. It is found that the corresponding type I error rates of the POET are again very close to the nominal value of 0.05 (results not shown here for brevity). All these results indicate that the POET controls the size very well, even though the sample size is not large.

Based on the power calculation formula (4) of the POET, we first obtain the sample size needed for the test to gain 80% analytical power, when there is imprinting. For this particular sample size, we then evaluate the actual power by simulation with 10 000 replicates. Table 3 lists the required sample sizes and the actual powers associated with them. It is observed that the sample sizes needed for the test to gain 80% power are very large in some scenarios but quite modest in others. However, for common diseases with large γ2, the sample sizes needed to gain 80% power are small to moderate and so it is practical to use this approach. We also conducted the simulation with marker allele frequency g=0.4 and with the other parameter values the same as those given in Table 3 (results omitted for brevity). All the simulation results show a very strong agreement between the analytical powers and the actual powers. So the power calculation Equation (4) appears very accurate.

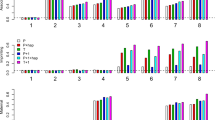

The sample sizes are chosen respectively as 100, 200 and 400 to exhibit the effect of the degree of imprinting I on the actual power of the POET via simulation with 100 000 replicates. Figure 1 depicts the actual power function of the POET when the degree of imprinting changes from the leftmost point φd/d(1−γ2)/2 to the rightmost point φd/d(γ2−1)/2. The power at I=0 (i.e. under the null hypothesis) is very close to 0.05, as expected. The symmetry of the power function about I=0 (as mentioned earlier) is confirmed in Figure 1.

As expected, we observe that the power is a monotonically increasing function of the sample size n or the absolute value of the degree of imprinting ∣I∣. The rightmost point of I, φd/d(γ2−1)/2, corresponding to γ1p=γ2 and γ1m=1, or equivalently φD/d=φD/D and φd/D=φd/d, means that the disease allele D is complete maternal imprinting or complete paternal expression. In this situation (and also at the leftmost point of I), the difference between the expression of the paternally derived allele and that of the maternally derived allele reaches its greatest extent. This kind of differential expression should be the easiest one to detect. The upper right part of Figure 1 shows that in our case, for moderate disease allele frequency p=0.1, the modest imprinting effects are easy to detect.

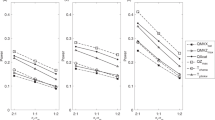

In addition to the simulation studies given above, we would also like to investigate the power of the POET for a small to medium sample size of 100 or 200, with parameters taking the following values: the disease allele frequency p∈[0.05, 0.35], the marker allele frequency g∈[0.1, 0.5], φd/d∈[0, 0.1], φD/D∈[0.8, 1], and the degree of imprinting I=(φD/D−φd/d)/2. More precisely, we calculate the power of the POET for p with increments of 0.01, g with 0.1, φd/d with 0.02, and φD/D with 0.04. Thus, we have 31 × 5=155 powers of the POET for given φd/d and φD/D. It is observed from the results that the bigger the difference between φD/D and φd/d, the more powerful the POET, assuming all other parameter values are fixed. The mean and standard deviation of those 155 powers with given φd/d and φD/D can be obtained accordingly. For a sample size n=100, when φd/d=0.1 and φD/D=0.8, the corresponding mean and standard deviation are 80.13 and 20.08% respectively. When φd/d=0.0 and φD/D=0.8, the corresponding values are 98.70 and 4.90%. For a bigger sample size n=200, the power increases considerably. For example, when the sample size n=200, φd/d=0.1 and φD/D=0.8, the mean and standard deviation of the corresponding powers of the POET are 93.70 and 12.08%, respectively. In summary, for the parameter values listed in the beginning of this paragraph, the power of the POET is relatively high. Notice that based on our Equation (4), it is possible to know the power of the POET for a given sample size and set of parameter values.

Discussion

The POET was developed to test for imprinting when association between the marker locus and a DSL is present. Furthermore, from the expression of E(NF>M−NM>F), we know that it is also appropriate to use the POET to test for association if there is imprinting. The POET can therefore be thought of as a test for imprinting in the presence of known association, or as a test for both imprinting and association.

The primary benefit of the POET is that it is appropriate in situations where the marker locus need not be the DSL per se and where the female and male recombination fractions are sex-specific. One attractive feature of the POET is that it uses the same marker genotype data (from affected children and their parents) collected for testing for linkage by the TDT, and so no extra data are needed. In fact, the TDT uses the families in which there is at least one heterozygous parent at the marker locus and tests for the equality of the expected number of times of the marker allele M1 transmitted and the expected number of times not transmitted from the heterozygous parents to the affected children. The POET uses the families in which the two parents' marker genotypes are different and tests for the equality of the expected number of families in which the father carries more copies of the marker allele M1 than the mother and the expected number of families in which the mother carries more copies of the marker allele M1 than the father. Our POET uses data of 10 family types of Table 1, namely types 1–10, while the TDT uses 11 types (1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 12, 13, and 14). The TDT has been commonly used and is a powerful tool for testing for linkage when the case–parents trios are available. We believe that the POET would be an equally effective way of testing for imprinting. These two tests are employed for different purposes, but both are simple and easy to use. Moreover, the POET, like the TDT, is also applicable to the population not in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (simulation results are omitted for brevity), for example, the population stratification demographic model.

The statistical methods for testing for linkage incorporating imprinting effects generally have greater power than the usual statistical methods ignoring imprinting effects, if the gene is actually imprinted (Wu et al., 2005). So it is important to test if the trait of interest is imprinted. Here we propose a simple test, using the case–parents trios, to detect imprinting effects. Many of the known imprinted genes influence fetal development, so incorporating imprinting effects into linkage analysis may be particularly useful for study of development-related traits such as birth weight (Bartolomei and Tilghman, 1997; Hanson et al., 2001). Notice that the POET is not valid when there are maternal effects (e.g. effects mediated through the intrauterine environment by the mother). In a future study, we will focus on the improvement of the TDT when there is a prior belief of imprinting for the trait of interest, and the development of test statistics for testing for imprinting effects in the presence of maternal effects.

References

Amos CI (1994). Robust variance-components approach for assessing genetic linkage in pedigrees. Am J Hum Genet 54: 535–543.

Bartolomei MS, Tilghman SM (1997). Genomic imprinting in mammals. Annu Rev Genet 31: 493–525.

Broman KW, Murray JC, Sheffield VC, White RL, Weber JL (1998). Comprehensive human genetic maps: individual and sex-specific variation in recombination. Am J Hum Genet 63: 861–869.

Deng HW, Chen WM (2001). The power of the transmission disequilibrium test (TDT) with both case–parent and control–parent trios. Genet Res 78: 289–302.

Falls JG, Pulford DJ, Wylie AA, Jirtle RL (1999). Genomic imprinting: implications for human disease. Am J Pathol 154: 635–647.

Fann CSJ, Ott J (1995). Parsimonious estimation of sex-specific map distances by stepwise maximum likelihood regression. Genomics 29: 571–575.

Feenstra B, Greenberg DA, Hodge SE (2004). Using lod scores to detect sex differences in male–female recombination fractions. Hum Hered 57: 100–108.

Haghighi F, Hodge SE (2002). Likelihood formulation of parent-of-origin effects on segregation analysis, including ascertainment. Am J Hum Genet 70: 142–156.

Hanson RL, Kobes S, Lindsay RS, Knowler WC (2001). Assessment of parent-of-origin effects in linkage analysis of quantitative traits. Am J Hum Genet 68: 951–962.

Haseman JK, Elston RC (1972). The investigation of linkage between a quantitative trait and a marker locus. Behav Genet 2: 3–19.

Knapp M (1999). A note on power approximations for the transmission/disequilibrium test. Am J Hum Genet 64: 1177–1185.

Morison IM, Paton CJ, Cleverley SD (2001). The imprinted gene and parent-of-origin effect database. Nucleic Acids Res 29: 275–276.

Ott J (1999). Analysis of Human Genetic Linkage, 3rd edn. The Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore and London.

Pfeifer K (2000). Mechanisms of genomic imprinting. Am J Hum Genet 67: 777–787.

Rao CR (1973). Linear Statistical Inference and Its Applications. John Wiley: New York.

Reik W, Walter J (2001). Genomic imprinting: parental influence on the genome. Nat Rev Genet 2: 21–32.

Risch N, Merikangas K (1996). The future of genetic studies of complex human diseases. Science 273: 1516–1517.

Shete S, Amos CI (2002). Testing for genetic linkage in families by a variance-components approach in the presence of genomic imprinting. Am J Hum Genet 70: 751–757.

Shete S, Zhou X, Amos CI (2003). Genomic imprinting and linkage test for quantitative-trait loci in extended pedigrees. Am J Hum Genet 73: 933–938.

Smalley SL (1993). Sex-specific recombination frequencies: a consequence of imprinting? Am J Hum Genet 52: 210–212.

Spielman RS, McGinnis RE, Ewens WJ (1993). Transmission test for linkage disequilibrium: the insulin gene region and insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM). Am J Hum Genet 52: 506–516.

Strauch K, Fimmers R, Kurz T, Deichmann KA, Wienker TF, Baur MP (2000). Parametric and nonparametric multipoint linkage analysis with imprinting and two-locus-trait models: application to mite sensitization. Am J Hum Genet 66: 1945–1957.

Van den Oord EJCG (2000). The use of mixture models to perform quantitative tests for linkage disequilibrium, maternal effects, and parent-of-origin effects with incomplete subject-parent triads. Behav Genet 30: 335–343.

Weinberg CR (1999). Methods for detection of parent-of-origin effects in genetic studies of case–parents triads. Am J Hum Genet 65: 229–235.

Wilkins JF, Haig D (2003). What good is genomic imprinting: the function of parent-specific gene expression. Nat Rev Genet 4: 359–368.

Wu CC, Shete S, Amos CI (2005). Linkage analysis of affected sib pairs allowing for parent-of-origin effects. Ann Hum Genet 69: 113–126.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the valuable comments made by the editor and two reviewers on an early draft of this paper. We thank David Wilmshurst for editorial assistance. This work was partially supported by a CRCG Seed Grant of The University of Hong Kong and funding from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (10329102, 10561008) and the Scientific Research Fund of Huaihua University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix A

Derivation of the conditional probabilities in

Table 1 The first family type 100 in Table 1 is taken as an example to illustrate how the conditional probabilities listed in the last column of Table 1 are derived. In order to find the conditional probability P(FMC=100∣child is affected), it is necessary to calculate P(F=M1M2, M=M2M2, C=M2M2, child is affected), which is the sum of the following four terms by the law of total probability: P(F=M1M2, M=M2M2, C=DM2/DM2)φD/D, P(F=M1M2, M=M2M2, C=DM2/dM2)φD/d, P(F=M1M2, M=M2M2, C=dM2/DM2)φd/D, P(F=M1M2, M=M2M2, C=dM2/dM2)φd/d where the left haplotype of the slash / is paternal and the right one is maternal. The first term (ignoring factor φD/D) can be further written as a product of two probabilities, P(F=M1M2, CP=DM2)P(M=M2M2, CM=DM2), where CP and CM denote respectively the paternal and maternal haplotypes at the marker locus and the DSL. For the first probability, considering all possible ordered genotypes at the marker locus and the DSL and seeing whether there is recombination between these two loci, we have

which is just w6 listed in the footnote of Table 1 after some transformations. The second probability is just w3 by the same principle. So P(F=M1M2, M=M2M2, C=DM2/DM2)=w3w6. Similarly, we have P(F=M1M2, M=M2M2, C=DM2/dM2)=w4w6, P(F=M1M2, M=M2M2, C=dM2/DM2)=w3w8 and P(F=M1M2,M=M2M2, C=dM2/dM2)=w4w8. Finally, we have the expression of the conditional probability P(FMC=100∣child is affected).

Appendix B

Proof for asymptotic normality of the POET

Theorem

-

Let u=(u1, …, um)T, v=(v1, …, vm)T, uivi=0, ui2=ui, vi2=vi (i.e. ui=0 or 1 and vi=0 or 1), for any i, (N1, ⋯, Nm, Nm+1)T be a multinomially distributed random variable of size n=∑i=1m+1Ni and with parameters (s1,…, sm, sm+1), where sm+1=1−∑i=1msi. Denote N=(N1, …, Nm)T, then the distribution of

tends to the normal distribution with mean

tends to the normal distribution with mean  and variance 1−(a1−a2)2/(4(a1+a2))−3(a1−a2)2/(4(a1+a2)2), where a1=uTs, a2=vTs, and s=(s1, …, sm)T.

and variance 1−(a1−a2)2/(4(a1+a2))−3(a1−a2)2/(4(a1+a2)2), where a1=uTs, a2=vTs, and s=(s1, …, sm)T.

Proof

-

Note that N/n is the maximum likelihood estimator of the parameter vector s and from the asymptotic normality of the maximum likelihood estimator, we have in law

where ∑=(σij)m × m, σii=si(1−si) and σij=−sisj for i≠j (Rao, 1973). It follows immediately that

Let

then we have

where the derivative ∂g/∂x is evaluated at x1=uTs and x2=vTs. After some matrix multiplication, we complete the proof.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, JY., Hu, YQ. & Fung, W. A simple method for detection of imprinting effects based on case–parents trios. Heredity 98, 85–91 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.hdy.6800906

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.hdy.6800906

tends to the normal distribution with mean

tends to the normal distribution with mean  and variance 1−(a1−a2)2/(4(a1+a2))−3(a1−a2)2/(4(a1+a2)2), where a1=uTs, a2=vTs, and s=(s1, …, sm)T.

and variance 1−(a1−a2)2/(4(a1+a2))−3(a1−a2)2/(4(a1+a2)2), where a1=uTs, a2=vTs, and s=(s1, …, sm)T.