Abstract

Progress in thermonuclear fusion energy research based on deuterium plasmas magnetically confined in toroidal tokamak devices requires the development of efficient current drive methods. Previous experiments have shown that plasma current can be driven effectively by externally launched radio frequency power coupled to lower hybrid plasma waves. However, at the high plasma densities required for fusion power plants, the coupled radio frequency power does not penetrate into the plasma core, possibly because of strong wave interactions with the plasma edge. Here we show experiments performed on FTU (Frascati Tokamak Upgrade) based on theoretical predictions that nonlinear interactions diminish when the peripheral plasma electron temperature is high, allowing significant wave penetration at high density. The results show that the coupled radio frequency power can penetrate into high-density plasmas due to weaker plasma edge effects, thus extending the effective range of lower hybrid current drive towards the domain relevant for fusion reactors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Driving current in high-density plasmas is essential for the progress of thermonuclear fusion energy research based on the tokamak concept1. The externally launched lower hybrid (LH) wave, producing the lower hybrid current drive (LHCD) effect2,3,4, is potentially the most suitable tool for driving current at large radii of fusion relevant plasmas, consistent with the needs of the International Thermonuclear Experiment Reactor (ITER), now in construction phase5. An important requirement in ITER is that a high fraction of non-inductive current be driven sufficiently off-axis, complementing the inductive current that tends to peak at the magnetic axis after plasma start-up. This requirement can be satisfied by the bootstrap current (that is, the non-inductive current self-generated by particle Coulomb scattering) produced with a relatively radially broad pressure and density profile. ITER will require relatively high densities at the periphery of the plasma column: ne_0.8≈0.7−1×1020 m−3 at normalized minor radius r/a≈0.8, where r=a is the plasma minor radius at the last closed magnetic field surface; similar values are also required at the magnetic axis (that is, ne0≈ne_0.8). However, it is presently unknown whether the bootstrap current can by itself fulfil the required non-inductive current in the outer half of the plasma cross-section. In fact, the nuclear self-heating determines the plasma power density profiles, mostly by collisional slowing down of fusion alphas on thermal electrons. These profiles, in turn, dictate the character of turbulence and turbulent transport and, eventually, the thermal plasma and fusion product profiles. This circumstance would occur on the characteristic spatio-temporal scales of burning plasmas, which represent complex self-organized systems6. Thus, for a successful development of reactor-graded plasma operations, it would be very important to have different and flexible tools capable of producing and controlling steady-state profiles with a high fraction of non-inductive plasma current driven in the outer half of the plasma column. These tools would work compatibly with the aforementioned constraints of ITER on plasma density profile.

LH waves, coupled to plasmas by means of phased waveguide array antennas7, would in principle propagate and damp in high-density, high-temperature fusion plasmas through Landau damping on electrons at relatively high velocity in the tail of the distribution function. This implies that, for wave-phase velocity7, vΦ//≡c/n//≈(2.5–4)vthe, where the suffix '||' refers to the direction parallel to the equilibrium magnetic field, n// is the wavenumber component, vthe and c are the electron thermal velocity and light speed, respectively. This mechanism produces the LHCD effect2,4 confirmed in many experiments3,8,9 using antennas that launch LH waves with n|| low enough to satisfy the Landau damping resonance condition. Consequently, the experimental observations of LH power absorption have been interpreted as the consequence of an upshift and broadening of the launched n// spectrum produced by wave propagation in the toroidal geometry10 and by wave plasma interactions occurring at the plasma periphery11,12.

Unfortunately, the LH waves may not penetrate the plasma core of ITER13,14,15 because of plasma density fluctuations11,12,16,17,18,19,20,21,22. In the Joint European Torus (JET), signatures of LH wave penetration into the plasma core disappear at plasma edge densities in the range of ne_0.8≈0.3×1020 m−3 (and ne0≈0.5×1020 m−3), significantly lower than those necessary for ITER13,14,15. In previous experiments at Frascati Tokamak Upgrade (FTU)23, LH wave penetration occurred only up to a line-averaged density of ne_av≈1.3×1020 m−3 and edge density of ne_0.8≈0.4×1020 m−3, still too low to be ITER relevant24. Similarly, in Alcator C-Mod, the LHCD was not seen at ne_av≥1.5×1020 m−3 and was weaker than expected at ne_av≥0.8–1.0×1020 m−3 (depending on the choice of other plasma parameters)14. Such poor penetration of the coupled LH power cannot be attributed to mode conversion of LH waves into fast waves7 (favoured at high plasma density), as all these experiments were performed with the LH-accessibility condition satisfied because of the use of sufficiently high values of launched n// and plasma toroidal magnetic field strength.

To explain the experimentally observed lack of LH wave penetration at high edge densities, we must invoke either wave damping due to ionization and resistive losses7 or interactions with plasma density fluctuations16,17,18,19,20,21,22, including the nonlinear parametric instability (PI) effect11,12,16,17,20,21. The present work mainly considers the latter effect, and the results of this approach have led to experiments on FTU that successfully demonstrate the penetration of LH power in high-density plasmas.

Results

Pioneering work has been performed at Frascati with the aim of producing suitable conditions for LH wave penetration into the core of high-density plasmas by mitigation of the PI effect20,25,26. More recently, numerical investigations of PI11,12 have shown the following: (1) PI can broaden the launched n// spectrum, which strongly affects the LH power deposition profile in LHCD experiments; (2) PI effects can become so strong at high density that they prevent the coupled LH power from penetrating the plasma core; (3) high electron temperatures in the plasma periphery (at r/a≈0.8, hereafter referred to as Te_outer) should have a key role in mitigating the PI-induced spectral broadening and, consequently, allow LH wave penetration into the core of reactor-grade plasmas; (4) relatively high Te_outer may be produced in high-density plasmas by means of low particle recycling from the vessel wall (as diagnosed by the D-alpha spectroscopic signal detected in the vacuum vessel chamber during experiments). These conditions have been obtained in experiments by using a lithium-coated vessel interior, optimized gas fuelling (also assisted by pellet injection) and plasma shapes that minimize plasma–wall interactions. In these conditions, high temperatures are achieved in the plasma periphery as a consequence of the concomitant reduced particle flux and lower radiative losses in the scrape-off layer27. For typical tokamak plasma parameters, the LH spectral broadening should be strongly reduced when operating with high electron temperatures in the plasma periphery (roughly Te≥0.2 keV at r/a≈0.8) and with low Te values (≤30 eV) only within a very narrow layer (typically of a few centimetres) at the antenna–plasma interface. These model predictions and guidelines for operation have been used to design the new experiments performed in FTU. As a result, the coupled radio frequency power has been combined with a diminished spectral broadening, resulting in current drive in the plasma core.

Experiments

The experimental results that will be presented here confirm the theoretical predictions and extend the range of usefulness of the LHCD effect to regimes of importance for fusion power-plants.

High-density plasmas have been produced in a wide range of parameters (toroidal magnetic field: BT=5T–8T, plasma current: IP=0.36–0.7 MA) and in standard conditions, consisting in the plasma displaced towards the toroidal (internal) limiter, the vessel wall coated with boron and the plasma fuelled by gas injection. The FTU plasma major radius on the axis is R0=0.935 m and the minor radius of main plasma at the last closed magnetic field surface is a=0.285 m. The generation of LH-accelerated supra-thermal electrons has been detected by a fast electron Bremsstrahlung (FEB) camera using hard X-ray emission detection28. Figure 1a shows the trend of the hard X-ray emission level due to LH-accelerated electrons at different plasma densities. The experimental points connected by dashed lines refer to plasmas with three different sets of plasma current and magnetic field in the standard conditions. The dotted line refers to plasmas in a new regime described later in the paper. In the standard regime, the FEB signal remains at the noise level for ne_av≥1.3×1020 m−3. In these conditions, the coupled LH power appears to be fully deposited at the very edge of the plasma. This behaviour cannot be explained in terms of LH wave inaccessibility, as these experiments have an antenna spectrum higher than the critical value (n//crit≈1.75) for LH wave mode conversion into fast waves.

(a) The fast electron Bremsstrahlung (FEB) camera on the central equatorial chord has been used. The standard (dashed lines) and high Te_outer (dotted line) regimes are shown. Different operating conditions are used in the standard regime: toroidal magnetic field BT=5.2 T and plasma current IP=0.36 MA (red squares), BT=5.9 T, IP=0.51 MA (black triangles), BT=7.1 T, IP=0.51 MA (blue triangles). The circles and triangle in green refer to the high Te_outer regime, performed with BT=5.9 T and IP=0.59 MA. The coupled LH power is PLH≈0.35 MW in all cases, except PLH≈0.52 MW in the case indicated by the green triangle. The error bar corresponds to 1 s.d. (b) Radial profiles of the hard X-ray level in high-density plasmas performed in high Te_outer regime. r/a is the normalized plasma radius, a is the plasma minor radius at the last closed magnetic field surface. The cases of three different operating plasma densities are shown: ne_av=1.6×1020 m−3 (red curves), ne_av=1.7×1020 m−3 (blue curves), ne_av=1.9×1020 m−3 (green curves). PLH=0.35 MW. Toroidal magnetic field: BT=0.59 T, plasma current: IP=0.59 MA. The error bar corresponds to 1 s.d.

To produce higher Te_outer, the flexibility of FTU has been exploited to use a lithium-coated vessel and proper gas fuelling operations, as described in the Methods section. For these conditions, hereafter referred to as the 'high Te_outer regime', experimental points denoted by dotted lines in Figure 1a were produced, indicating a change in the behaviour of the accelerated electrons compared with the standard regime. In this new regime, the LH effect persists to densities that are a factor two higher than those in standard regime.

Figure 1b shows the radial profiles of the hard X-ray signal detected for three high-density plasmas (ne_av>1.5×1020 m−3) in the high Te_outer regime. The energy range of the LH-accelerated plasma electrons is 40–200 keV and the coupled LH power is deposited in the core, mainly at r/a=0.3–0.4. The radial profiles of the LH-driven current density are expected to have the same shape as the hard X-ray profile, as routinely assumed in tokamak experiment modelling. The high Te_outer regime plasmas have densities much higher than those in the standard regime (increased by 40–90%) and much lower core electron temperatures will consequently occur at the same plasma current. As it is necessary to have regimes with similar core Te when comparing LH effects, a slightly lower plasma current has been used in the standard regime (reduced by 10–35%, the lowest current case referring to the one with the lowest target density). In this way, the following typical conditions have been produced: Te0≈1 keV in the standard regime; and Te0≈0.7 keV in the new regime plasmas with 70% higher density.

The time traces of the main plasma parameters of four relevant FTU experiments are shown in Figure 2. Figure 2a compares plasma discharges of the two regimes with similar parameters. At the start of the LH pulse, a significantly different Te_outer is obtained (more than a factor two at r/a≈0.65–0.95, see boxes 3 and 4 of Fig. 2a). This difference (and the reason for the name 'high Te_outer regime') was predicted to be sufficient to reduce the PI-induced spectral broadening and favour LH penetration into the plasma core11,12. In both experiments, the LH power (0.35 MW) was coupled during the plasma current flattop (starting at t≈0.1 s) when the line-averaged density was ne_av≈1.4×1020 m−3 for the standard regime and ne_av≈1.9×1020 m−3 for the high Te_outer regime. In the case of the high Te_outer regime, the hard X-ray signal becomes markedly higher than the noise level during the LH pulse (see Fig. 2a, box 4), a sign that the coupled LH power has penetrated and interacted with the plasma core. The standard regime does not show this signature. In high Te_outer regime, experiments performed with the same parameters as the plasma in Figure 2a, but with a higher coupled LH power (0.52 MW instead of 0.35 MW), show a more pronounced increase in the hard X-ray signal (by a factor of two) and a higher central temperature (by 35%) as seen in Figure 2b. A clear increase in the central electron temperature also occurs during the LH power-coupling phase, giving a further indication that, in high Te_outer regime, LH power penetrates to the plasma core. The hard X-ray signal starts to strongly decrease at t=0.78 s when the LH power is still on and the edge temperature, Te_0.95, has decreased (from 80 to 50 eV) to values close to the corresponding standard regime (see box 4 of Fig. 2a,b). This indicates that higher Te_outer enhances the LH wave interaction with a high-density plasma core and that the plasma edge should be further heated to sustain the LHCD effects for longer times.

(a) Two high-density plasma discharges are shown. Standard regime (discharge 32323, red colour), high Te_outer regime (discharge 32555, blue colour). Toroidal magnetic field BT=6.0 T. Plasma current: IP=0.52 MA in pulse 32323, and IP=0.59 MA in pulse 32555. Plasma density (box 1), central (box2) and edge electron temperature (at r/a≈0.65, box 3; at r/a≈0.95, box 4), hard X-ray level (box 5), LH power (box 6). r/a is the normalized plasma radius, a is the plasma minor radius at the last closed magnetic field surface. (b) Two high-density plasma discharges performed in the high Te_outer regime are shown. Same operating parameters (BT=6.0 T, IP=0.59 MA), but different coupled LH power: 0.35 MW (discharge 32555, red colour), 0.52 MW (discharge 32557, blue colour). Plasma density (box 1), central (box 2) and edge electron temperature (at r/a≈0.65, box 3, at r/a≈0.95, box 4), hard X-ray level (box 5), LH power (box 6).

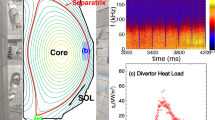

Kinetic profiles evolution is compared in Figure 3 for two pairs of experiments performed in the standard and high Te_outer regimes. For each experiment, two time points are considered, one just before and one during the LH power-coupling phase. The density profiles in Figure 3a are obtained using a multichord CO2 and CO laser scanning interferometer. Both discharges in the standard regime have high plasma densities (ne_av>1×1020 m−3) for which the signatures of LH-accelerated electrons are not observed (see Fig. 1a). In the standard regime case, the core plasma density is significantly lower than in the high Te_outer case, but in one of the standard regime plasmas, the density at the periphery is slightly higher. This allows the role of different edge plasma densities to be compared in the two regimes. Figure 3b shows the electron temperature profile in the outer plasma region using electron cyclotron emission (ECE) Michelson interferometer and Thomson Scattering (TS) diagnostics, the latter only being used when LH-generated hard X-rays disturbing the ECE diagnostic are produced. Langmuir probes have been used to diagnose the scrape-off layer kinetic profiles. In both standard regime plasmas, the electron temperature was Te≤100 eV within a radial gap of about 10 cm (far away from the antenna location), which is about a factor of two lower than in the cases in the high Te_outer regime. During the LH power-coupling phase, the density profiles exhibit only minor changes. The Te profile remains unchanged in the standard regime, whereas higher temperatures are produced in the high Te_outer regime, increasing with LH-coupled power. These results further confirm the consistency of a higher Te_outer operation with the occurrence of LH wave effects in the plasma core in high-density plasmas.

(a) Plasma density profiles in standard and high Te_outer regimes. r/a is the normalized plasma radius, a is the plasma minor radius at the last closed magnetic field surface. Two standard regime plasmas are shown: pulse 32323 (BT=6.0 T, IP=0.52 MA), black curves: before LH phase (t=0.61 s, continuous curve) and during LH phase (t=0.64 s, dashed curve); pulse 32164 (BT=5.2 T, IP=0.36 MA), blue curves: before LH phase (t=0.61 s, continuous curve) and during LH phase (t=0.64 s, dashed curve). Two high Te_outer regime plasmas are shown: pulse 32555 (BT=6.0 T, IP=0.59 MA), green curves: before LH phase (t=0.71 s, continuous curve), during LH phase (t=0.74 s, dashed curve); pulse 32557 (BT=6.0 T, IP=0.59 MA), red curves: before LH phase (t=0.71 s, continuous curve), during LH phase (t=0.74 s, dashed curve). The error bar corresponds to 1 s.d. (b) Electron temperature profiles. Standard regime: pulse 32323 (BT=6.0 T, IP=0.52 MA), black curves: before LH phase (t=0.61 s, continuous curve), during LH phase (t=0.64 s, dashed curve); pulse 32164 (BT=5.2 T, IP=0.36 MA), blue curves: before LH phase (t=0.61 s, continuous curve), during LH phase (t=0.64 s, dashed curve). High Te_outer regime: pulse 32555 (BT=6.0 T, IP=0.59 MA), green curves: before LH phase (t=0.71 s, continuous curve), during LH phase (t=0.74 s, dashed curve); pulse 32557 (BT=6.0 T, IP=0.59 MA), red curves: before LH phase (t=0.71 s, continuous curve), during LH phase (t=0.74 s, dashed curve). The radial size of the scrape-off plasma (between last closed magnetic field surface and LH antenna mouth) is 0.022 m. The error bar corresponds to 1 s.d.

The experiments in FTU benefit from the use of an LH spectral broadening monitor provided by a radio frequency probe located outside the machine at a port several metres from the LH launcher. This diagnostic technique has proved to be useful for monitoring wave–plasma edge interactions in LH experiments in tokamaks8,11,12,18,20. Figure 4 shows the spectral broadening measurements obtained during two experiments, one in the standard regime (Fig. 4a) and one in the high Te_outer regime (Fig. 4b). In the standard regime case, the spectral broadening is about 15 MHz (at around 35 dB below the pump power level) and about 7 MHz in the high Te_outer regime case. In the considered experiments, the linear wave scattering effect 18,22 that is expected to broaden the radiofrequency probe spectrum up to about 2.5MHz in both regimes, would be responsible for the similar broadening (of about 2MHz) occurring in Figures 4a and b at around 20dB below the pump power peak. In the next section, we show that the related strong dependence of the LHCD effect on Te_outer and the radio frequency probe spectral broadening in the range 7–15 MHz are consistent with predictions made by numerical simulations of PI11,12.

(a) Standard regime. The spectrum has been detected by radio frequency probe during the plasma discharge 32164 (BT=5.2 T, IP=0.36 MA). The signal is 10 dB above the noise level at the frequency of 7997 MHz that is swept at the LH power switch-on time point (t=0.612 s). (b) High Te_outer regime. The spectrum has been detected during the plasma discharge 32555 (BT=6.0 T, IP=0.59 MA). The signal remains at the noise level at the frequency of 7997 MHz that is swept at the LH power switch-on time point (t=0.712 s).

Simulations

Modelling of the plasma current evolution has been performed by the JETTO code29 using the measured magnetic data, kinetic profiles and LH-driven radial current density profile modelled by the LHstar code11,12. The same approach has been used as that which previously produced modelling results in agreement with measured data in important current drive experiments at JET11,12,31 and FTU28. In the case of higher coupled LH power (PLH=0.52 MW), the proportionally higher hard X-ray signal (see Fig. 2b, box 4) is accompanied by a higher central electron temperature (Te0≈0.8 keV instead of Te0≈0.6 keV, see Fig. 2b, box 2) and a lower loop voltage (by about 20%) with respect to the case with standard LH power (PLH=0.35 MW). As the density profile and impurity concentration are similar in these plasmas (effective ion charge: Zeff≈1), the difference in temperature can be attributed only to the higher coupled LH power. Moreover, no significant changes in the Te profile occurs just after the start of the LH pulse (in particular, at the radial location r/a≈0.3–0.4 in which the LH deposition indicated by FEB signal has its maximum). Instead, the higher Te0 in the case with higher LH power occurs on a time scale of 40 ms, which corresponds to the evolution of current density profile and transport. On this time scale, a higher current density is produced in the plasma core by the coupled LH power. Figure 5 shows the evolution of the profiles of safety factor (top box) and magnetic shear (bottom box) at two time points just before and during the LH-power coupling phase. The LH deposition profiles used in the JETTO code are consistent with the measured hard X-ray profiles. The LH-driven current leads to the formation of a local negative shear (≈−0.5 in the region r/a≈0.3–0.4), the effect being more pronounced in the case of higher LH-coupled power, and accompanied by a reduced electron thermal conductivity (by about 20% in the inner half of the plasma). In comparable experiments performed without LH power, no significant change in temperature and current density profiles was seen. A possible interpretation of this result is that, operating at ITER-relevant plasma densities and with sufficiently high peripheral plasma temperature, the launched LH waves penetrate and drive current in the plasma core, which, in turn, produces an improvement in plasma confinement through the generation of a low magnetic shear32.

The top panel represents the safety factor, whereas the bottom panel is the magnetic shear. r/a is the normalized plasma radius, a is the plasma minor radius at the last closed magnetic field surface. Two different time points are shown: before (at 0.68 s, continuous curves) and during (at 0.74 s, dashed curves) LH power coupling. The blue and magenta curves refer, respectively, to the case with coupled LH power of 0.35 MW and 0.52 MW.

Using the LHstar code, which is described by Cesario et al.11,12, the PI-induced spectral broadening has been calculated and used to determine the LH deposition in the plasma. Frequencies and growth rates of the ion-sound-quasi-mode-driven LH sideband waves are obtained by solving the parametric dispersion relation8,19:

where Σ is the dielectric function, ω, k indicate, respectively, the complex frequency and the wave vector of the low frequency perturbation, the suffix i=0,1,2 refers to the pump, the lower and the upper sidebands, respectively, and μ1,2 are the coupling coefficients referring to the lower and upper sidebands, respectively (see Cesario et al.12 for details). From the measured data in the standard regime, plasma (discharge 32164 in Figure 3) high growth rates (γ/ω0≈1×10−4) are obtained for the LH sidebands that are significantly shifted in frequency with respect to the pump wave (Δf≈15–20 MHz in frequency, and Δn//≈30 in wavenumber). The spatial amplification factor, which takes into account the convective loss due to plasma inhomogeneity19, for ion-sound quasi-mode-driven PI is given by Cesario et al.12

Using the parameters of the high Te_outer regime (plasma discharge 32555 of Fig. 2) and the antenna spectrum and PI-produced spectral broadening (up to n1//=7.5) as input to the ray-tracing and Fokker-Plank modules30 of the LHstar code, numerical results show that the coupled LH power is mostly deposited at r/a≈0.4 in the first radial pass (see Fig. 6, green curve). It is worth noting that the contribution of all PI-produced LH wave sidebands is essential to produce the LH-driven current density profile, although only a little power (≈0.1% of the pump power) is carried by the components with the highest wavenumber, consistent with the quasi-linear LH wave damping effect7,33. Numerical simulations also show that LH waves accelerate plasma electrons, mainly at the same radial location of r/a≈0.4, at energies in the range of 40–80 keV, which is consistent with the measured hard X-ray energetic spectra obtained in previous LHCD experiments28. Meanwhile, using the measured data from the standard regime (plasma discharge 32164 of Fig. 3) and the PI-induced spectral broadening (up to n//=30), the computed LH power deposition is localized very close to the plasma edge (see Fig. 6, red curve). In this case, very low-energy electrons are produced by the coupled LH power (tail electron temperature <10 keV), well below the FEB camera range of detection. This result is consistent with the detected FEB signal, which remains at the noise level in the high-density standard regime plasmas. Therefore, the creation by the LH sideband waves of an electron distribution function tail near the plasma edge is sufficient to damp the lower n// components of the pump. Future experiments at FTU will fully assess the role of PI by monitoring the low-frequency mode wavenumber spectrum at the plasma edge by cross-correlation of signal collected by Langmuir probes, and comparing with the spectra in frequency and n// of quasi-modes expected by modelling to drive the PI. A more accurate processing of the RF-probe signal will assess the occurrence of pump power depletion.

r/a is the normalized minor radius of the plasma column. The profiles have been obtained by modelling with the LHstar code, considering the parameters of two plasma discharges: standard regime, pulse 32164 (BT=5.2 T, IP=0.36 MA, red curve); high Te_outer regime, pulse 32555 (BT=6.0 T, IP=0.59 MA, green curve).

The effects of wave-produced ionization and resistive losses7 have been considered as a possible further cause for the LH edge deposition in the standard regime. These effects have been calculated to be around 2–3% in a single radial pass in the most pessimistic edge conditions (that is, considering the case of lowest temperature in the standard regime: pulse 32164 in Figure 3, wherein the neutral density is less than 1017 m−3). These effects would thus require many full radial passes to cause the full absorption of the coupled LH power at the plasma edge. But this kind of wave propagation would produce some n// upshift of the launched antenna spectrum, effect of wave propagation in the toroidal plasma geometry); consequently, some wave interaction with tail electrons of the plasma core should occur, which is inconsistent with the absence of signatures of wave-accelerated plasma electrons in the high-density standard regime.

Discussion

This experiment confirms the theoretical prediction that operating at a relatively high temperature at the plasma periphery is the key to reducing the PI-produced spectral broadening, and to allowing the penetration of LH waves into power-plant-relevant high-density plasmas.

Effects of ionization and resistive loss7, which may cause full damping of the coupled radio frequency power at the very plasma periphery in the FTU standard regime, do not have a dominant role. Indeed, these effects (of the order of 1%) are generally insufficient to explain the observed lack of LH power penetration in JET, in which the much higher core electron temperature (Te0≈6 keV), compared with that in FTU, results in LH power that is mostly deposited during the first radial pass13,15. It is more likely in both cases that the PI produces strong single-pass wave damping at the edge, thus having a dominant role15.

Correlated with LH power penetration in the core, spectral broadening measured by radio frequency probes is significantly smaller than that in reference plasmas without the diminished PI, consistent with the theoretical predictions that have motivated this experiment11,12. The hard X-ray emission from the suprathermal electron population, generated by the LH waves in these favourable conditions, is considerably increased even at densities that have so far been considered the upper limit for efficient LHCD operation in FTU, namely, line density ne av≈1.3×1020 m−3, central density ne0≈1.5×1020 m−3, peripheral density (at r/a≈0.8) ne_0.8≈0.4×1020 m−3. LHCD effects are now detected on FTU at ne_av≈2×1020 m−3, ne0≈5×1020 m−3 and ne_0.8≈0.85×1020 m−3.

The plasma-wall temperatures expected in the ITER device (namely, Te<100 eV for r/a=1.007–1.10)34 are in the range of parameters considered in FTU experiments in the standard regime. Therefore, the present work is useful for assessing the potential impact of LH current drive as a tool in a revised ITER design. In ITER, useful conditions should be produced to avoid the launched n// spectrum from being strongly broadened as it propagates through the cold layer of the plasma edge, which would prevent the LH wave penetration into the plasma core35. Recent experiments at JET indicate that this undesirable condition can actually occur15, but the related FTU results show how the problem can be solved.

The LH wave penetration and current drive produced in FTU at reactor-grade plasma densities provide a change of paradigm for driving current in tokamak plasmas by externally launching radio frequency power. This leads to a further understanding of a crucial issue in fusion science, and in providing the knowhow to extend the range of usefulness of the LHCD effect to regimes of critical importance for fusion reactors.

Methods

Experimental device description

FTU is a medium-sized high magnetic field (up to 8 T) tokamak with a toroidal major radius on the axis of 0.93 m and a minor radius of 0.3 m. The machine produces plasmas with densities at or above the level of a reactor (line-averaged density up to 4×1020 m−3) with a plasma current flattop of 1.5 s duration. The experiments described here have been performed with the option of displacing the plasma, with a circular cross-section, both towards the toroidal limiter, which is located on the high field side and has a relatively large plasma–wall contact area (of about 1.7 m2), or towards the poloidal limiter, located on the low field side, which has a much smaller plasma–wall contact surface (about 0.026 m2).

FTU operations

FTU tools allow comparable high-density plasma regimes to be exploited with different electron temperatures at the plasma periphery. This capability provides the necessary conditions for testing the LH wave penetration and current drive effect, which linear theory expects to be produced at reactor-grade plasma densities, but which the results of previous experiments did not confirm. Two different configurations have been exploited, with plasma displaced towards the two limiter structures. Using the toroidal limiter, a stronger plasma–wall interaction occurs because of the larger plasma–wall contact area. In these conditions, lower particle recycling from the vessel wall and relatively low temperature at the plasma periphery generally occur. Conversely, in operation with the plasma displaced towards the poloidal limiter, the D-alpha emission level is about 10 times smaller, and slightly higher electron temperatures are observed at the plasma edge than in similar experiments using the toroidal limiter.

FTU can operate with a vacuum vessel covered either by boron or lithium. Such coatings are both useful for improving plasma operations and reducing the plasma impurity content. With lithium, sprayed on the walls from the limiter, where it is present in liquid form35, the plasma is particularly protected from fluxes of impurities with high values of effective electric charge, and is characterized by a level of recycling significantly lower than with a boron-coated vessel35,36,37.

Pellet injection has also been exploited to produce the initial plasma conditions needed in these LHCD experiments. FTU has a pneumatic single-stage multibarrel pellet injector38, capable of firing up to eight pellets per plasma discharge, with a typical velocity of 1.3 km s−1 and a mass of the order of 1020 deuterium atoms. The FTU pellet operations are characterized by deep-core fuelling, which produces high-density plasmas exhibiting a phase with relatively high electron temperature at the periphery of the plasma.

To reduce recycling further, the technique of extra-gas fuelling in the early phase of discharge has been used. In the standard gas-fuelling technique, the requested density value at the start of the LHCD pulse is set by the plasma density feedback control, which generally produces a continuous gas injection during the whole plasma discharge. Relatively high levels of recycling and low temperatures at the plasma periphery are obtained with this operation. In the technique of extra-gas fuelling in the early phase of discharge, a large amount of gas is injected in the early phase of discharge (but still during the plasma current flattop), which transiently produces a plasma density slightly higher than the value required for the LHCD pulse. The density then falls to the required value after a delay, during which a pause in gas injection is programmed, so that low recycling occurs. This fuelling technique has been used to prepare plasmas with both very high density and low recycling by means of pellets fired during the pause in the gas injection.

Using all these methods, the highest temperatures at the plasma periphery have been produced in high-density plasmas, meeting the requirements of the experiment.

Systems of additional heating and current drive

Three additional heating and current drive systems are available on FTU: LHCD (operating frequency: 8 GHz, coupled radio frequency power more than 2 MW), Electron Cyclotron resonant heating (operating frequency: 140 GHz, coupled radio frequency power up to 1.6 MW) and Ion Bernstein Wave heating (operating frequency: 0.433 GHz, coupled radio frequency power up to 1 MW). In the experiments presented here, only the LHCD system has been used: two antennas are available in two FTU ports, each consisting of three grills superimposed poloidally. Each grill is an array of 4 rows and 12 columns of active and phase-controlled rectangular waveguides. Each grill is fed by a gyrotron radio frequency power source and, given FTU compactness, has small dimensions: Lz (toroidal)=8 cm, Ly (poloidal)=14 cm. The peak of the antenna spectrum, n// Peak, can be adjusted continuously in the range of 1.5–3.8; n// Peak=1.83–0.2, corresponding to a waveguide phasing of 90 degrees with 90% directivity, has been used here. The discussed experiments have been conducted using only one antenna grill. Further experiments are planned on FTU in which the ECRH system will be used to produce further local heating of the plasma periphery by appropriately setting the toroidal magnetic field. In this way, the related LHCD regimes at reactor-grade plasma densities should be further sustained.

Production of plasma discharges

About forty FTU plasma discharges have been produced in two regimes at reactor-grade high plasma densities characterized by different electron temperatures at the plasma periphery. The standard regime described in this paper has been produced using a boron-coated vessel, with the plasma column displaced towards the toroidal (internal) limiter and using the standard gas-fuelling technique. In these conditions, high-density plasmas have been obtained with a relatively low electron temperature at the plasma periphery. The plasma current was 0.35 or 0.52 MA and the toroidal magnetic field was 5.2 or 5.9 T, respectively.

The high Te_outer regime described in the paper has been obtained using a lithium-coated vessel, plasma displaced towards the poloidal (external) limiter, extra-gas fuelling in the early phase of the discharge and pellet injection. The pellet has been fired (at t=0.7 s) just before the LH power switch-on (with a 0.012 s delay) to prevent enhanced pellet ablation. The velocity and size of the pellets have been sufficient to produce the desired fuelling in the plasma core. A plasma current IP=0.6 MA and a toroidal magnetic field BT=5.9 T have been used. The slightly lower magnetic field also used in the standard regime has been useful for obtaining similar safety factors and plasma stability conditions in the two regimes.

Hard X-ray measurements

The generation of LH-accelerated supra-thermal electrons has been detected by a high performance FEB camera detecting hard X-ray emitted in the direction perpendicular to the confinement magnetic field. The FEB has a time resolution of 4 μs and uses two independent pinhole cameras with 15 lines of sight each28. Considering the poloidal cross-section of the torus, the horizontal camera is centred at an angle of 0 degree, and the vertical one is centred at an angle of −90 degree (on the bottom). Both cameras are identical, including the viewing angles. For each line of sight, there is a CdTe detector with a thickness of 2 mm and a square surface of 25 mm2. The absorbers and screens used allow transmission for an energy range from 20 to 200 keV. The detector is closely connected to an appropriate preamplifier.

Electron temperature measurements

The evolution of the plasma electron temperature profile has been monitored by ECE and TS measurements. Both diagnostics have confirmed the occurrence, in the high Te_outer regime, of the central temperature increase produced by LHCD. In the high Te_outer regime the edge temperature has been only from the TS diagnostic, as the ECE temperature measurements in the periphery are affected by some supra-thermal emission located in the spectrum between the first and second harmonic (where the plasma is optically thin), because of the effect of the second harmonic downshift extending to the very plasma edge.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Cesario, R. et al. Current drive at plasma densities required for thermonuclear reactors. Nat. Commun. 1:55 doi: 10.1038/ncomms1052 (2010).

Change history

19 September 2013

A correction has been published and is appended to both the HTML and PDF versions of this paper. The error has not been fixed in the paper.

References

Freidberg, J. Plasma Physics and Fusion Energy (Cambridge University Press, 2007).

Fisch, N. J. Confining a tokamak plasma with rf-driven currents. Phys. Rev. Lett. 41, 873–876 (1978).

Bernabei, S. et al. Lower hibrid current drive in the PLT tokamak. Phys. Rev. Lett. 49, 1255–1258 (1982).

Fisch, N. J. Theory of current drive in plasmas'. Rev. Mod. Phys. 59, 175–234 (1987).

Ikeda, K. Progress in the ITER physics basis. Nucl. Fusion 47, S1–S414 (2007).

Fasoli, A., Gormenzano, C., Berk, H. L., Breizman, B., Briguglio, S. & Darrow, D.S. Physics of energetic ions. Nucl. Fusion 47, S264–S284 (2007).

Brambilla, M. Kinetic Theory of Plasma Waves (Oxford Press, 1999).

Porkolab, M. et al. Observation of lower hybrid current drive at high densities in the alcator C tokamak. Phys. Rev. Lett. 53, 450 (1984).

Karney, C. F. F., Fisch, N. J. & Jobes, F. C. Comparison of the theory and practice of lower hybrid current drive. Phys. Rev. A 32, 2554 (1985).

Bonoli, P. & Englade, R. C. Simulation model for lower hybrid current drive. Phys. Fluids 29, 2937 (1986).

Cesario, R., Cardinali, A., Castaldo, C., Paoletti, F., Mazon, D. & the EFDA-JET Contributors. Modelling of lower hybrid current drive in tokamak plasmas by including the spectral broadening induced by parametric instability. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 175002 (2004).

Cesario, R., Cardinali, A., Castaldo, C., Paoletti, F., Fundamenski, W., Hacquin, S. & the JET-EFDA workprogramme Contributor, Spectral broadening of lower hybrid waves produced by parametric instability in current drive experiments on tokamak plasmas. Nucl. Fusion 46, 462–476 (2006).

Kirov, K. K. et al. LH wave absorption and current drive studies by application of modulated LHCD at JET Proc. 36th European Phys. Society Conf. on Plasma Physics, Sofia, Bulgaria, 2009.

Wallace, G. et al. Observation of Lower Hybrid Wave Absorption in the Scrape-Off Layer of a Diverted Tokamak, in Radio Frequency Power in Plasmas, Proceedings of the 18th Topical Conference, Gent, Belgium (eds Bobkov, V. & Noterdaeme, J. M.), 24–26 June 2009 (American Institute of Physics, 2009) 395–398.

Cesario, R. et al. Plasma edge density and lower hybrid current drive in JET. submitted to Phys. Rev. Lett.

Porkolab, M. Theory of parametric instability near the lower-hybrid frequency. Phys. Fluids 17, 1432–1442 (1974).

Chen, L. & Berger, R. Spatial depletion of the lower hybrid cone through parametric decay. Nucl. Fusion 17, 779–785 (1977).

Andrews, P. I. & Perkins, F. W. Scattering by lower-hybrid waves by drift-wave density fluctuations: solutions of the radiative transfer equation. Phys Fluids 26, 2537–2557 (1983).

Liu, C. S. & Tripathi, V. K. Parametric Instabilities in a magnetized plasma. Phys. Rep. 130, 143–216 (1986).

Cesario, R. & Cardinali, A. Parametric instabilities excited by ion-sound and ion-cyclotron quasi-modes during lower hybrid heating of tokamak plasmas. Nucl. Fusion 29, 1709–1719 (1989).

Castaldo, C., Lazzaro, E., Lontano, M. & Sergeev, A. M. Spectral broadening of lower hybrid waves due to ponderomotive effects. Phys. Lett. A 230, 336–346 (1997).

Pericoli-Ridolfini, V., Calabrò, G., Panaccion, E. L. & FTU team and ECH team Study of lower hybrid current drive efficiency over a wide range of FTU plasma parameters. Nucl. Fusion 45, 1386–1395 (2005).

Gormezano, C. et al. Highlights of the physics studies in the FTU. Fusion Sci. Technol. 45, 297–302 (2004).

Pericoli-Ridolfini, V. et al. High plasma density lower hybrid current drive in the FTU Tokamak. Phys. Rev. Lett. 82, 93–96 (1999).

De Marco, F. Review of current drive experiments at the lower hybrid frequency, in Proc. Course and Workshop on Applications of Radiofrequency Waves to Tokamak Plasmas, Varenna, Italy, Monography (eds Bernabei, S., Gasparino, U., & Sindoni, E.) 316–342 (International School of Plasma Physics, 1985).

Alladio, F. et al. Lower hybrid experiments at 8 GHz in FT (Frascati Tokamak), 15th European Conf. on Controlled Fusion and Plasma Heating, Dubrovnik, May 1988 (ed. Heijn Petten, J.) Vol. 12B part III, 878–881 (European Physical Society, 1988).

Post, D. E. & Behrisch, R. Physics of Plasma-Wall Interactions in Controlled Fusion (NATO ASI Series, Series B, Physics, Plenum Press, 1986).

Cesario, R. et al. Lower hybrid wave produced supra-thermal electrons and fishbone-like instabilities in FTU. Nucl. Fusion 49, 075034 (2009).

Cenacchi, G. & Taroni, A. The JET equilibrium-transport code for free boundary plasmas (JETTO), in Proc. 8th Comput. Phys., Comput. Plasma Phys., Eibsee 1986 Vol. 10D, 57–60 (EPS, 1986).

Cardinali, A. Quasi-linear absorption of the lower hybrid wave in tokamak plasmas. Recent research developments in plasmas. Transworld Res. Netw. Mag. 1, 185–197 (2000)

Cesario, R. et al. Lower hybrid current drive in experiments for transport barriers at high of JET (Joint European Torus), in Proc. of the 17th Topical Conf. on Radio Frequency Power in Plasmas, Clearwater, Florida, USA, 7–9 May 2007 (eds Ryan, P. M. & Rasmussen, D. A.) Vol. 933, 265–268 (American Institute of Physics, 2007).

Levinton, F. M. et al. Improved confinement with reversed magnetic shear in TFTR. Phys. Rev. Lett. 75, 4417–4420 (1995).

Succi, S., Appert, K. & Vaclavik, J. Generation of suprathermal electrons interacting with waves in lower hybrid range of frequency revisited. Plasma Phys. and Contr. Fusion 27, 863–871 (1985).

Colas, L., Milanesio, D., Faudot, E., Goniche, M. & Loarte, A. Estimated RF sheath power fluxes on ITER plasma facing components. J. Nucl. Materials 390–391, 959–962 (2009).

Cesario, R., et al. in Proc 35th Conf. Controlled Fusion Plasma Phys., 9–13 June 2008, Crete, Greece, 2.106 (2008).

Apicella, M. L. et al. First experiments with lithium limiter in FTU. J. Nucl. Mat. 363–365, 1346–1351 (2007).

Abdou, M. A., et al. & The Apex Team On the exploration of innovative concepts for fusion chamber technology. Fusion Eng. Design. 54, 181–247 (2001).

Krasheninnkov, S. I., Zakharov, L. E. & Pereverzev, G. V. On lithium walls and performance of magnetic fusion devices. Phys. Plasmas 10, 1678–1682 (2003).

Frigione, D. et al. Steady improved confinement in FTU high field plasmas sustained by deep pellet injection. Nucl. Fusion 41, 1613–1618 (2003).

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs S. Bernabei, C.D. Challis, M. Ferrari, G. Giruzzi, F. Napoli, A. Polevoi, and E. Pollura for the very helpful discussions, and the technicians M. Aquilini, S. Di Giovenale, A. Grosso, P. Petrolini, V. Piergotti, B. Raspante, G. Rocchi, A. Sibio and B. Tilia who have helped to carry out the experiment. Special thanks to M. Cecchini, B. Giovannetti and F. Miglietta for their editorial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

R.C. designed and coordinated the experiment; L.A., A.C., C.C., R.C., M.M., L.P., V.P., F.S. and O.T. produced the diagnostics' measurements and modelling of the radio frequency power propagation, deposition and driven current drive; D.F. coordinated the operations with the pellet injector, and M.L.A. and G.M. the operations of lithium coating of the vacuum vessel wall. All the authors contributed to carrying out the experiments and to preparing the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cesario, R., Amicucci, L., Cardinali, A. et al. Current drive at plasma densities required for thermonuclear reactors . Nat Commun 1, 55 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms1052

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms1052

This article is cited by

-

Rethinking radiation effects in materials science using the plasma-focused ion beam

Journal of Materials Science (2022)

-

Electron acceleration by wave turbulence in a magnetized plasma

Nature Physics (2018)

-

Radio-frequency current drive for thermonuclear fusion reactors

Scientific Reports (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.