Abstract

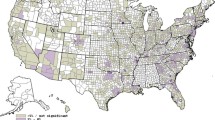

Objective: Infant mortality has been reduced dramatically with the development of perinatal regionalized high-technology care. Our objective was to assess use of high technology care among women with high-risk pregnancies in the urban and rural United States. Methods: The 1988 National Maternal and Infant Health Survey was linked to the 1988 American Hospital Association survey of all obstetrical hospitals. Hospitals were classified into five levels of care based on services and staffing. Women were classified as having high-risk pregnancies using two definitions: (1) gestational age <34 weeks and birthweight <1500 g (High Risk I) and (2) the first definition or an antenatal high-risk medical diagnoses (High Risk II). Analyses assessed the proportion of high-risk women delivering in appropriate locations in the rural and urban United States and explored how personal characteristics, insurance status, and use and source of prenatal care influenced where high-risk women delivered. Results: 71.2% of High Risk I and 55.9% of High Risk II women delivered in a high-technology facility (Level IIA or III). Fifty percent of HRI rural women delivered in tertiary high-technology hospitals and 39% of HRII rural women delivered in a high-technology hospital. High-risk urban women were two to three times more likely to deliver in a high-technology facility compared to their rural counterparts. The multivariate analysis showed that Black high-risk women were more likely to deliver in a high-technology setting and that receipt of prenatal care in a private setting lowered the odds of delivering in a high-technology setting when other factors were controlled. Conclusions: In an era where regionalized perinatal care was not threatened by managed care, a large proportion of high-risk women received care in less than optimal settings. Rural high-risk women delivered in high-technology hospitals less often than their urban counterparts. The multivariate analyses implied that the potential barriers to care may be more important among those considered more socially advantaged, who may be more at the mercy of managed care. The current reimbursement environment, which discourages referral to specialists and high-technology care, could result in less access today.

Similar content being viewed by others

REFERENCES

Buehler JW, Strauss LT, Hose CJR, Smith JC. Birth weightspecific causes of infant mortality, United States. Public Health Reports 1987;102(2):162–71.

MacDornan MF, Atkinson JO. Infant mortality from the 1997 period linked birth/infant death dataset. National Vital Statistics Reports [National Center for Health Statistics, Hyattsville, Md] 1999;47(23).

Hack M, Fanaroff AA. Changes in the delivery room care of the extremely small infant (<750 g): Effects on morbidity and outcome. N Engl J Med 1986;314:660–64.

Paneth N, Kiely JL, Wallenstein S, et al. Newborn intensive care and neonatal mortality in low-birth-weight infants: A population study. N Engl J Med 1982;307:149–55.

Cooke RWI. Referral to a regional center improves outcome in extremely low birthweight infants. Arch Dis Childhood 1987;62:619.

Cordero L, Backes CR, Zuspan FP. Very low birthweight infants: Influence of place of birth on survival. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1982;143:533.

Mayfield JA, Rosenblatt RA, Baldwin LM, Chu J, Logerfo JP. The relation of obstetrical volume and nursery level of perinatal mortality. Am J Public Health 1990;80:819.

Rosenblatt RA, Mayfield JA, Hart LG, Baldwin LM. Outcomes of regionalized perinatal care in Washington state. West J Med 1988;149:99.

Siegel E, Gillings D, Campbell S, Guild P.A controlled evaluation of rural regional perinatal care: Impact on mortality and morbidity. Am J Public Health 1985;75:246–53.

Gortmaker S, Sobel A, Clark C, et al. The survival of very low birth weight infants by level of hospital of birth: A population study of perinatal systems in four states. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1985;152:517–24.

Nugent RR. Perinatal regionalization in North Carolina, 1967–1979: Services, programs, referral patterns, and perinatal mortality rate declines for very low birthweight infants. NC Med J 1982;43:513–15.

Bowes WA Jr. A review of perinatal mortality in Colorado, 1971 to 1978, and its relationship to the regionalization of perinatal services. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1981;141:1045–52.

Kirby RS. Perinatal mortality: The role of hospital of birth. J Perinatol 1996;16:43–49.

Powell SL, Holt VL, Hickok DE, Easterling T, Connell FA. Recent changes in delivery site of low-birth-weight infants in Washington: Impact on birth weight-specific mortality. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1995;173(5):1585–92.

South Carolina Regionalization Surveillance System: Report of the prenatal indicators for 1983–1991, Vols. 1 and 2. South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control, 1992.

Committee on Perinatal Health. Toward improving the outcome of pregnancy. White Plains, NY: The March of Dimes National Foundation, 1977.

Merenstein MC, Rhodes PG, Little GA. Personnel in neonatal pediatrics: Assessment of numbers and distribution. Pediatrics 1985;76:454–56.

Schwartz RM. Supply and demand for neonatal intensive care: Trends and implications. J Perinatol, 1996;16(6):483–89.

Guild PA, Schectman R, Noll D. Consensus in region IV: Maternal and infant health and family planning indicators for planning and assessment level 6 steps. Center for Health Services Research, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, September, 1997.

Schwartz RM, Muri JH, Zhao R, Caldwell DL, Gagnon DE. Florida perinatal high risk study. National Perinatal Information Center final report, submitted to Children's Medical Services, December 1995.

National Center for Health Statistics. Healthy people 2000 review, 1998–1999. Hyattsville, Md: Public Health Services, 1999.

Hughes DC, Runyan SJ. Prenatal care and public policy: Lessons for promoting women's health. J Am Med Womens Assoc. 1995;50(5):156–59, 163.

Braveman P, Bennett T, Lewis C, Egerter S, Showstack J. Access to prenatal care following major medicaid eligibility expansion. JAMA 1993;269:1285–89.

Piper JM, Mitchel, EF, Ray WA. Expanded Medicaid coverage for pregnant women to 100 percent of the federal poverty level. Am J Prevent Med 1994;10:97–102.

Sanderson M, Placek PJ, Keppel KG. The 1988 National Maternal and Infant Health Survey: Design, content, and data availability. Birth 1991;18:1.

Blackmore-Prince C, Kieke B, Kugaraj KA, Ferre C, Elam-Evans LD, Krulewitch CJ, Gaudino JA, Overpeck M. Racial differences in the patterns of singleton preterm delivery in the 1988 National Maternal and Infant Health Survey. Maternal Child Health J. (in press).

Shah BV, Barnwell BG, Beiler GS. SUDAAN user's manual, release 7.1. Research Triangle Park, NC: Research Triangle Institute, 1996.

Bronstein JM, Capilanto E, Carlo WA. Access to neonatal intensive care for low birthweight infants: The role of maternal characteristics. Am J Public Health 1995;85(3):357–61.

Kogan MD, Martin JA, Alexander GR, et al. The changing pattern of prenatal care utilization in the United States using different prenatal care indices. JAMA 1998;279(20):1623–28.

Stata statistical software, version 4.0. College Station, TX: Stata Corporation, 1995.

Gagnon D, Allison-Cooke S, Schwartz RM. Perinatal care: The threat of deregionalization. Pediatric Ann 1988;17:447–52.

Phibbs CS, Bronstein, JM, Buxton E, Phibbs RH. The effects of patient volume and level of care at the hospital of birth on neonatal mortality. JAMA 1996;276(13):1054–59.

Larson EH, Hart LG, Rosenblatt RA. Is non-metropolitan residence a risk factor for poor birth outcome in the US? Soc Sci Med 1997;45(2):171–88.

Ware J, Bayliss MS, Rogers WH, et al. Differences in 4-year health outcomes for elderly and poor, chronically ill patients treated inHMO and fee-for-service systems: Results from the medical outcomes study. JAMA 1996;376:1039–47.

Hedgecock J, Castro M, Cruikshank WB. Community health centers: Aresource for service and training. Henry Ford Hosp Med J 1992;40:45–49.

Lubchenco LO, Butterfield LJ, Delaney-Black V, et al. Outcome of very low-birthweight infants: Does antepartum versus neonatal referral have a better impact on mortality, morbidity, or long-term outcome? Am J Obstet Gynecol 1989;160: 5539–45.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schwartz, R.M., Muri, J.H., Overpeck, M.D. et al. Use of High-Technology Care Among Women with High-Risk Pregnancies in the United States. Matern Child Health J 4, 7–18 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009537817450

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009537817450