Abstract

This article challenges the idea that there could be a convincing secular version of the principle that human life is sacred, and explores the significance this has for the law. A number of secular justifications for the claim that there is something intrinsically, as opposed to instrumentally, valuable about human life have been mooted, most eloquently by Ronald Dworkin. While secular explanations for the sanctity of human life are undeniably attractive, this article will maintain that they do not have logic on their side. Having argued that the ‘sanctity principle’ makes sense only as an article of religious faith, the implications this has for the law are explored. In relation to end-of-life decision-making, the sanctity principle has been invoked to justify a sharp line between deliberately ending life and failing to prolong it. This article will conclude by arguing that a rejection of the sanctity principle might, in certain circumstances, cause us to focus instead on the extent to which death harms someone.

Similar content being viewed by others

The principle that there is something intrinsically sacred about human life has had considerable resonance for the law. It might be said to ground a belief in the importance of human rights, and it has clearly influenced the law's treatment of issues as diverse as euthanasia and research on embryos. My purpose in this article is to argue that the principle of the sanctity of human life (hereafter the sanctity principle) in fact only makes sense when grounded in a certain sort of religious belief. Many prominent theorists, among them Ronald Dworkin, have attempted to fashion secular versions of the sanctity principle. While such attempts are superficially appealing, in my view they fail. If the sanctity principle has no coherent secular basis, and makes sense only as an adjunct of religious faith, its foundational role within a secular legal system should be challenged.

I take for granted that there is a crucial difference between saying that human life is very valuable or very important, and saying that it is sacred. If the sanctity principle was just a particularly forceful way of expressing the view that human life is precious, then I would embrace it wholeheartedly, and its influence over law and policy would not matter. But saying something is sacred is importantly different from saying that it is extremely precious. Following Ronald Dworkin's definition of what it means to say that human life is sacred, I shall assume that the sanctity principle entails the claim that there is something intrinsically, as opposed to just instrumentally valuable about human life (Dworkin, 1993).Footnote 1 That is, that in assessing the value of a human life, its relative benefits and burdens are irrelevant; a human life is valuable just because it is a human life, regardless of its subjective value (or otherwise) to the person whose life it is.

My purpose in this article is to challenge the idea that human life is always intrinsically valuable, and that its deliberate destruction is always necessarily a bad thing. Of course, in the vast majority of cases, the deliberate destruction of a human life is one of the gravest wrongs it is possible to imagine. This is because death eliminates everything that has been invested in a person's life, as well as foreclosing all of the experiences which that life might yet hold. There are, however, a tiny number of human lives which contain no more experiences at all, or only intolerable suffering. Contrary to the sanctity principle, I will argue that the wrongness of killing may, in these exceptional cases, depend upon the extent to which death is a harm. On an instrumental view of the value of human life, there may be cases when the deliberate destruction of a human life is not wrong, but, on the contrary, would be the right thing to do.

It is important to note that the sanctity principle is not the same as what John Keown (2006) has called ‘vitalism’, that is, the idea that human life should be preserved at all costs. The sanctity principle proscribes the deliberate destruction of human life, it does not demand that life should always be prolonged for as long as possible. It might therefore be argued that the law's recognition that it can sometimes be legitimate to withdraw life-prolonging treatment, such as mechanical ventilation or artificial nutrition and hydration, is not so much an exception to the sanctity principle as an embodiment of it.

It is not my purpose in this article to offer a wholesale critique of the acts/omissions distinction. Rather, as I have argued elsewhere, there are usually very important differences between acts and omissions in terms of establishing both causation and moral blameworthiness (Jackson, 2004). I am concerned here only with the difference between the withdrawal of life-prolonging treatment and killing, when it will generally be equally easy (or difficult)Footnote 2 to establish causation. The sanctity principle has been invoked by the judiciary in order to draw a line between the moral blameworthiness of treatment withdrawal and killing, whereas I will argue later that a rejection of the sanctity principle would cause us to focus instead on whether death harms the person who dies.

In the first section of this article, I shall briefly flesh out my claim that the sanctity principle has had considerable resonance for the law by offering some examples of its influence over end-of-life decision-making. Next, I will evaluate whether it would be possible to construct a coherent secular justification for the claim that human life is sacred. I conclude that, while intuitively attractive, the sanctity principle, with its commitment to the intrinsic value of lives which have ceased to contain anything of value, does not make sense, other than as an article of religious faith. I go on to examine the consequences this has for the wrongness of killing. Death is, of course, usually a very great harm, but, for the small number of people for whom it has become ‘the lesser of two evils’ (Kamm, 2001), or even better than the alternative, the sanctity principle works, in practice, to prolong the process of dying.

The sanctity principle at work

Richard Stith has argued that ‘the primary attribute of sacred things is that they may not be violated, not that they must be produced or preserved’ (1991). So, for a patient in a permanent vegetative state, ‘the sanctity of her life requires that she not be destroyed, but the low value of her life seems to justify not preserving it’ (1991). Crucially, therefore, while the sanctity principle condemns the deliberate destruction of a human life, it does not mean that life-prolonging treatment must be provided indefinitely. Consistently with the sanctity principle, Andrew McGee has argued that there is an important moral difference between killing a patient by giving them a lethal injection and withdrawing treatment which is currently keeping them alive:

the moral relevance of the distinction can therefore be put in this way: euthanasia interferes with nature's dominion, whereas withdrawal of treatment restores to nature her dominion after we had taken it away when artificially prolonging the patient's life. (2005: 383, emphasis in original)

This version of the sanctity principle—which offers a moral basis for the acts/omissions distinction—has been helpful for the courts when they have been faced with decisions about the lawfulness of withdrawing life-prolonging treatment, such as mechanical ventilation or artificial nutrition and hydration (ANH), from patients who lack capacity.

In Airedale NHS Trust v. Bland [1993] the House of Lords were clear that, in Lord Keith's words, it is ‘the concern of the state, and the judiciary as one of the arms of the state’ to maintain ‘the principle of the sanctity of life’, but they also were unanimously of the view that this did not rule out the withdrawal of ANH from a patient in a permanent vegetative state (PVS).Footnote 3 In the Court of Appeal, Hoffmann LJ (as he then was) explained this especially clearly. He claimed that ‘most of us would be appalled if he [Tony Bland] was given a lethal injection’, and that this is ‘connected with our view that the sanctity of life entails its inviolability by an outsider’. Human life, according to Hoffmann ‘is inviolate even if the person in question has consented to its violation’. On the other hand, he argued that

… we do not impose on outsiders an unqualified duty to do everything possible to prolong life as long as possible. I think that the principle of inviolability explains why, although we accept that in certain cases it is right to allow a person to die … we hold without qualification that no one may introduce an external agency with the intention of causing death.Footnote 4

We can see similar reasoning in Re J (Wardship: Medical Treatment) [1991] when the Court of Appeal was faced with the question of whether it would be lawful to withhold mechanical ventilation if, as was likely, baby J suffered another respiratory collapse. J had severe brain damage, was a spastic quadriplegic, probably without sight, speech or hearing, but he was able to feel pain. Taylor LJ restated the court's ‘high respect for’ the sanctity principle and its proscription of the deliberate destruction of a life, but again he stressed that this did not mean that steps always had to be taken to prolong life:

As a corollary to [the court's high respect for the sanctity of human life], it cannot be too strongly emphasized that the court never sanctions steps to terminate life. That would be unlawful. There is no question of approving, even in a case of the most horrendous disability, a course aimed at terminating life or accelerating death. The court is concerned only with the circumstances in which steps should not be taken to prolong life.

The House of Lords in Bland found themselves able to authorize a procedure which would inevitably lead to Tony Bland's death, but they could do this only by deciding that the provision of ANH had become futile. Once treatment can be described as ‘futile’, it can lawfully be withdrawn, with the effect that Tony Bland would die slowly, albeit painlessly, from dehydration and starvation. Similarly, in Re J,the decision to withhold treatment which would lead to baby J's death was justified by describing the treatment as both burdensome and futile. Lord Donaldson MR did not say that it would be better for J if his life was brought to an end, but rather that treatment ‘which will cause increased suffering and produce no commensurate benefit’ could be withheld. Taylor LJ agreed. While he was ‘of the view that there must be extreme cases in which the court is entitled to say: “The life which this treatment would prolong would be so cruel as to be intolerable”’, this could be achieved only by saying that ‘deliberate steps should not be taken artificially to prolong its miserable life span’, rather than by deliberately shortening the child's life.

I would argue that, in both of these cases, we can see the influence of the sanctity principle. In each case, the decision had been taken that a course of action which would lead to the patient's death was compatible with the best interests test. Indeed, a majority in the House of Lords explicitly accepted that the doctors’ intention in withdrawing artificial nutrition and hydration was, in Lord Browne-Wilkinson's words, to ‘bring about the death of Anthony Bland’. Lord Lowry said that ‘the intention to bring about the patient's death is there’, and Lord Mustill admitted that ‘the proposed conduct has the aim … of terminating the life of Anthony Bland’ (my emphasis).

In each case, however, life could be brought to an end only because the doctors had recourse to a course of action which could plausibly be described as a ‘failure to prolong life’. The doctors and judges might have decided that it would better if the patient died sooner rather than later, but the sanctity principle works to ensure that only certain types of death—namely those achieved by suffocation, dehydration, starvation and infection, through the withdrawal or withholding of, respectively, ventilation, ANH and antibiotics—can lawfully be brought about. Even where, as in Bland, the intention is clearly to bring about the patient's death, the sanctity principle prohibits doctors from acting to deliberately achieve that end quickly, and I would argue more humanely, by the administration of a single lethal injection. Lord Browne-Wilkinson drew attention to this paradox in Bland:

… the conclusion I have reached will appear to some to be almost irrational. How can it be lawful to allow a patient to die slowly, though painlessly, over a period of weeks from lack of food but unlawful to produce his immediate death by a lethal injection, thereby saving his family from yet another ordeal to add to the tragedy that has already struck them? I find it difficult to find a moral answer to that question. But it is undoubtedly the law.

The sanctity principle's influence is also visible in a piece of recent legislation (Coggan, 2007). Section 4(5) of Mental Capacity Act 2005 (MCA) states that when deciding whether to provide life-sustaining treatment to someone who lacks capacity, the person making the determination ‘must not, in considering whether the treatment is in the best interests of the person concerned, be motivated by a desire to bring about his death’ (my emphasis). The Code of Practice reiterates that doctors are still entitled to determine that life-prolonging treatment may be futile and/or burdensome, and therefore that its non-provision (which will result in the patient's death) may be in a patient's best interests, provided that they do not ‘desire’ the inevitable consequence of treatment withdrawal (Ministry of Justice, 2007). According to the Code, a ‘desire’ to bring about the person's death, ‘even if this is from a sense of compassion’, is unacceptable (Ministry of Justice, 2007).

It is possible that section 4(5) will have a chilling effect on medical practice, because doctors working in intensive care units who choose to withdraw life-prolonging treatment in the certain knowledge that it will bring the patient's life to an end might worry that they could be said to ‘desire’ this inevitable outcome, and hence that they would be acting unlawfully by withdrawing treatment. After all, if a doctor thought death was actually undesirable, then it is difficult to see how she would be acting properly by withdrawing life-prolonging treatment. But, as the Code of Practice makes clear, forcing doctors to continue to provide life-prolonging treatment indefinitely is certainly not the purpose of this oddly worded provision. (It is noteworthy that the government deliberately chose not to use the word ‘intend’, with its clear and established legal meaning). Rather I would argue that section 4(5)—which was a late-stage amendment to the bill designed to mollify opponents who had argued that it introduced ‘euthanasia by the back door’—should be read as a largely symbolic statutory commitment to the sanctity principle. Since I believe that the sanctity principle's influence over the law has been unhelpful, and, as I argue in the next sections, unwarranted, it is unfortunate that a statutory version of it has been appended to the Mental Capacity Act.

Let me turn now to the central claim which underpins my argument in this article, namely that because the claim that human life is sacred is essentially a religious principle, the hold it has exercised over legal decision-making should be subject to challenge. This, as I explain later, will have important implications for the proscription of medicalized killing.

The religious sanctity principle

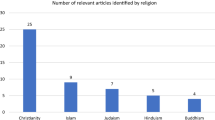

It is important to remember that not all religions believe that human life, and only human life, is sacred. Many religions do not regard humans as inherently different from, and superior to, other animals. Eastern religions, such as Jainism and Hinduism for example, advocate much more respect for animal life than do Western religions, and take for granted human beings’ continuity with other animals.

For Jews and Christians, however, the sanctity principle has its origins in Genesis, the first book of the Bible: God made man ‘in his own image’, and ordered him to ‘have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over every living thing that moveth upon the earth’. As well as being special because man was made in the image of God and was given power over other living things by God, human beings were also said to have souls which would survive death. These special features of humanness lead to the sanctity principle's central precept, namely that there is something especially heinous about deliberately ending a human life, regardless of whether the person's life contains anything that they are capable of valuing, or whether they themselves wish to continue living.

It would be a mistake to give the impression that there is a single religious view on human sanctity. Monotheistic religions, including Christianity, Judaism and Islam, share some common beliefs about the sacredness of human life, but there is little agreement, even within religions, on the consequences that flow from this. The Vatican, for example, has promulgated the view that from the moment of conception, it is wrong to deliberately destroy human life, and this view is shared by some evangelical Protestants. In contrast, many Anglicans believe that, in certain circumstances, embryo research and abortion can be morally acceptable (Brierly, 2006). The emphasis on healing within Judaism has persuaded some rabbinical scholars to endorse human embryonic stem cell research (Cooperman, 2002; Dorff, 2002).

Nevertheless, despite these differences both between and within religions, all who subscribe to the religiously inspired sanctity principle share the belief that simply because a life is human, it is intrinsically valuable. It is certainly not my intention in this article to criticize those whose religious beliefs inspire them to believe that there is something sacred about human life. On the contrary, I accept that, for someone who believes in a monotheistic God, the sanctity principle clearly makes sense. My argument is not that the sanctity principle is irrelevant for everyone. Rather my point is that, in a secular society, an essentially religious principle ought to be a matter of personal morality, and should not, without further justification, form the basis of law and public policy.

Although there are still those who believe that man was created by God in his own image, it is now widely accepted that human beings evolved from non-human animals by a process of natural selection. The principle that human life is sacred is not, however, the sole preserve of those who believe that God made the world in seven days, or even of those with less fundamentalist religious beliefs. On the contrary, it is shared by many who would claim not to have any religious faith at all. But does this make sense?

I would argue that closer scrutiny of the secular justifications for the sanctity principle reveals that they rest upon some rather shaky foundations. In the next sections, I will explore three such justifications. The first is Ronald Dworkin's argument that human life represents some sort of pinnacle of evolution, and that the sanctity principle captures our shared awe at the ‘miracle’ of evolutionary progress. The second is the view that humans are special because of a range of distinctive and sophisticated human traits and abilities. Finally, it is sometimes argued that we need to believe in the specialness of human beings because the consequences of doing otherwise are so terrible, with the Nazis commonly held up as the paradigm example of where a failure to respect the intrinsic sanctity of all human lives might take us.

These are powerful arguments, and instinctively very attractive ones. However, as I explain in the next sections, they do not have logic on their side.

Evolutionary awe

Ronald Dworkin assumes that most people share the ‘fundamental’ idea that:

… human life is intrinsically valuable, and worthy of a kind of awe, just because it is human life. They think that once a human life begins, it is a very bad thing—a kind of sacrilege—that it end prematurely, particularly through someone's deliberate act. (Dworkin, 1992: 406)

Importantly, because this view embodies the idea that human life is intrinsically rather than just instrumentally valuable, ending a human life is a bad thing regardless of whether death is, in fact, bad for the human being whose life ends. The value of human life hence ‘transcends subjective experience’ (Dworkin, 1992: 415). Central to our culture, according to Dworkin, is our ‘shared conviction’ that the life of each member of our species has intrinsic or sacred value. This means that human life should not just be protected in order to safeguard individual citizens’ rights and interests, but also because human life is ‘an objective or intrinsic good, a value in itself, quite apart from its value to the person whose life it is’ (Dworkin, 1992: 396).

But where does this ‘shared conviction’ in the intrinsic sanctity of human life come from, if not from a belief that life is a gift from God? In part, Dworkin believes that there is a shared sense of awe at the ‘miracle’ of human creation, which need not derive from the view that life was created by God:

Any human creature, including the most immature embryo, is a triumph of divine or evolutionary creation, which produces a complex, reasoning being from, as it were, nothing, and also of what we often call the ‘miracle’ of human reproduction, which makes each new human being both different from and yet a continuation of the human beings who created it. (Dworkin, 1993: 83–4)

John Mahoney makes a similar point:

The emergence of the human being even as a matter of chance in a blind cosmos is a genuine cause for wonder; and the product of the human species in the course of evolution is something to be wondered at with something approaching awe, or natural reverence. (2006: 163)

This ‘natural reverence’ for humanness does not simply derive from wonder at the biological process of human reproduction, rather Dworkin argues that we are also in awe of the human race's remarkable achievements:

… we treat the preservation and prosperity of our own species as of capital importance because we believe that we are the highest achievement of God's creation, if we are conventionally religious, or of evolution, if we are not, and also because we know that all knowledge and art and culture would disappear if humanity did. (Dworkin, 1993: 413–14)

But is it true that human beings are self-evidently evolution's ‘highest achievement’? There are many things human beings cannot do, such as fly or walk upside down or live underwater, and while some humans have been capable of extraordinary acts of creative genius, this is certainly not true of every human being. If one believes that we were made by God, in his own image, the view that mankind is His final triumph makes sense. If one does not believe this, then it seems clear that humans are part of evolution, but that they are not necessarily its triumphant end point. For most of the Earth's 4.57 billion years of existence, Homo sapiens, which is less than 250,000 years old, did not exist, and it can be predicted there will be a time in the future when there are no human beings left on the planet. We were not created by some divine spark, on an evolutionary view, but rather are a species which has evolved over millions of years from non-human animals.

In the end, I think Dworkin is on stronger ground when he admits that the belief in the sanctity of human life is a religious belief, even when it is not animated by a belief in God:

The belief that the value of human life transcends its value for the creature whose life it is—that human life is objectively valuable from the point of view, as it were, of the universe—is plainly a religious belief, even when it is held by people who do not believe in a personal deity. (Dworkin, 1992: 413)

A belief in the sanctity principle is religious in the sense that it is a matter of faith rather than reason or rational argument. Again, Hoffmann LJ in the Court of Appeal in Bland explained this particularly well:

… we have a strong feeling that there is an intrinsic value in human life, irrespective of whether it is valuable to the person concerned or indeed to anyone else. Those who adhere to religious faiths which believe in the sanctity of all God's creation and in particular that human life was created in the image of God himself will have no difficulty with the concept of the intrinsic value of human life. But even those without any religious belief think in the same way. In a case like this we should not try to analyse the rationality of such feelings. What matters is that, in one form or another, they form part of almost everyone's intuitive values. No law which ignores them can possibly hope to be acceptable. (my emphasis)

Hoffmann LJ thus admits that it is not sensible to analyse the rationality of the ‘feeling’ that human life is intrinsically valuable, and that it is enough that this forms part of ‘almost everyone's intuitive values’.

But is this good enough? With respect, should a shared intuition which cannot be analysed rationally govern legal decision-making? It is undoubtedly true that this intuition is widely shared, but this may have more to do with our shared upbringing in a particular culture than with its essential truth. As Martha Nussbaum has pointed out, ‘all philosophers writing in the modern Western tradition, whatever their religious beliefs, have been deeply influenced by the Judeo-Christian tradition, which teaches that human beings were given dominion over animals and plants’(2006: 328). John Gray has a less forgiving explanation. He has described the belief that humans are special as ‘Christianity's cardinal error’, and he is sharply critical of ‘those who have given up an irrational belief in God for an irrational faith in mankind’ (2002: 37).

Before we leave what Ngaire Naffine has described as Dworkin's ‘mystical’ approach to the sanctity principle (Naffine, unpublished), it is interesting to note that, unlike John Keown and John Finnis, two other enthusiastic advocates of the sanctity principle, Dworkin does not believe that a belief in the sanctity of human life is necessarily incompatible with the legalization of assisted dying. Dworkin contends that it is important for each life to go well, and when it is not going well, and never will, deliberately bringing it to an end might be legitimate. I agree with him on this point, but it is hard to see how giving priority to the individual's subjective experience of whether their life is going well is consistent with the sanctity principle's insistence that human life is intrinsically valuable, regardless of the value it has to the person whose life it is. Dworkin has argued that ‘the importance of human life transcends subjective experience’, and yet in accepting the legitimacy of assisted dying he must also believe the opposite, namely that the subjective experience of the individual will sometimes be more important than the intrinsic value of human life.

Empirical specialness

Regardless of whether the principle that human life is sacred derives from religious belief or is shared by those whose awe is at evolution and not creation, it is crucially important that it is very rarely concerned with the sanctity of life in general. We do not generally talk about the sanctity of a rabbit's life, or that of a geranium. Rather, with the exception of the sort of extreme radical biological egalitarianism advocated by Albert Schweitzer (1929) (who once described himself as a ‘mass murderer of bacteria’), the principle rests upon the assumption that there is something distinctive about human life which makes it more important and valuable than other sorts of life.

Most of the candidates for distinctively ‘human’ qualities which make our lives more valuable and satisfying than animal lives—such as consciousness, sentience, moral reasoning, self-awareness, creativity, inventiveness, etc.—are characteristics which are possessed by most but not by all humans. The problem with this justification for human sanctity is that there are members of our species who do not possess any of these qualities, and never will. Tony Bland had permanently and irrevocably lost the capacity for consciousness and sentience, though he was indubitably still alive. An anencephalic infant, born without much of the skull or brain, will never achieve consciousness or any semblance of self-awareness. If the special value of human lives derives from characteristics which mark us out from the animal kingdom, what is special about the life of a human being who permanently lacks those characteristics (Frey, 1996; Hughes, 1998)? Conversely, how should we treat animals which appear to possess at least some of these special ‘human’ characteristics?

In spite of irrefutable evidence that a chimpanzee's capacity for communication, emotion and self-awareness vastly outstrips that of a patient in a PVS or an anencephalic infant, the law nevertheless treats the PVS patient in the special manner reserved for all human beings, and treats the chimpanzee as a lower form of life. This is what Peter Singer (1989), following Richard Ryder,Footnote 5 describes as speciesism, and Mary Anne Warren (1997) calls ‘human chauvinism’.

Singer points out that, in the past, members of a particular gender or racial group considered themselves superior to others just because they were, for example, male and/or white. The belief that lives differ in value as a result of something as arbitrary as one's sex or the colour of one's skin now seems both absurd and offensive, but, according to Singer (1994), we fail to notice that we have set up an identical exclusionary line between human beings and other animals. If we are forced to admit, in Jeff McMahan's words, that there is ‘no morally significant essence that all the members of the human species have in common’, we have to acknowledge that ‘comembership of the human species is, like membership of the same race, a purely biological relation’ (2002: 225). As a result, Singer maintains that ‘we cannot justifiably give more protection to the life of a human being than we give to a nonhuman animal, if the human being clearly ranks lower on any possible scale of human characteristics than the animal’ (1989: 206).

Of course, one important difference between a severely impaired human being and a non-human animal is that the human being is someone's child or sibling or parent, and these relatives might be harmed if someone they loved was, for example, treated as a resource for scientific experiments in the same way as we might treat a non-human animal (Warren, 1997). But the logical extension of this consequentialist argument would be that where the severely impaired human has no family or friends, there is no one who is likely to be harmed if we were to treat her in the same way as an animal. If we were instead to say that the severely impaired human being's membership of our species demands that we treat her differently, we return to the difficult-to-defend position that simply being alive and human marks a being out as superior to all non-human animals.

We have a great deal of evidence that some animals are capable of intelligent thought and of empathy; animals can feel pleasure and pain, and even grief (Goodall, 1991; Patterson and Linden, 1982). Of course there is a danger of anthropomorphic projection onto animal behaviour, but the evidence is now overwhelming that not all animals are simply instinct-driven automatons, but instead that some are self-aware, and capable of engaging in complex reasoning and planning for the future (Wise, 2001).

I do not mean to suggest that animals can do everything of which human beings are capable: plainly that is not true. Contractarian models of justice and social responsibility, for example, inevitably exclude animals. Yet it is vitally important to remember that not all humans are included in a model of participatory democracy which presupposes a minimum level of capacity. Kantian moral philosophy, for example, which presumes a rational, self-interested, autonomous actor, undoubtedly excludes animals, but it also excludes those humans who lack the capacity to reason. If, as Lawrence Friedman has maintained, ‘modern law presupposes a society of free-standing, autonomous individuals’ (1994: 125) it inevitably sidelines a significant proportion of the population, who will never be either free-standing or autonomous.

James Rachels (1991) argues that, to the extent that humans and animals are similar, for example having the capacity to feel pain or fear, they should be treated similarly, while different characteristics, such as the use of language or having an interest in planning one's future, may permit differential treatment. A cat has an interest in being treated humanely, and having some freedom of movement; it does not have an interest in voting or learning how to read (DeGrazia, 2002). What matters, according to this line of argument, is the individual creature's capacities, rather than its membership of a particular species.

Against this, Carl Cohen has argued that the criteria which mark humans out as ‘special’ do not amount to a ‘test to be administered to human beings one by one’ (1986: 866). Rather according to Cohen, all human beings are of the same ‘kind’, and, unlike animals, it is a kind which is capable of exercising moral judgement, and of possessing rights. The fact that an individual human being cannot, in fact, exercise moral judgement does not stop them being of the kind that can. Michael Cox would agree. He argues that ‘what counts in establishing rights are the characteristics that a certain class of beings share in general, even if not universally’ (1978: 110). According to Cox, it would be ‘futile’ to search for attributes that all humans share, and so instead it is sufficient to focus on ‘capacities that are nearly or virtually universal among humans’ (1978: 110).

Of course, Cohen and Cox are right that species membership will generally offer a helpful ‘shortcut’ towards identifying a being's capacities and needs, and determining how it should be treated, but, because this is not always the case, and because of our tendency to prioritize ‘our own’, it is, according to Rachels (1991), dangerous to rely upon species membership alone. Perhaps one way out of this impasse is to draw a distinction between the criteria which justify giving an individual particular rights, which should depend on that individual creature's capacities; and species membership, which helps instead to tell us what concepts like flourishing and well-being mean for members of that species. So species membership will tell us what a good life might be for a human, and what a good life might be for a dog. We can therefore recognize that a human life which lacks the goods of a normal human existence is an impoverished one, even though it might be a reasonable life for a dog.

The barbarism of the Nazis and the rise of human rights

The idea that all human beings should be treated with equivalent concern and respect, and that all have lives of equal value, is undeniably attractive. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UN, 1948) was born of the profound horror at the barbaric way in which the Nazis singled out some human beings for treatment as if their lives did not matter. As Martha Nussbaum has argued, what the Nazis seemed to lack was a sense of the sanctity of human life. If we were to say that humans are not, in fact, special, Nussbaum worries that we would ‘lose our moral footing utterly’ (2001: 1511). On this view, promoting equality, and the interests of the most disadvantaged peoples of the world, relies upon the conviction that every human life is intrinsically and equally valuable. Richard Stith, for example, suggests that the sanctity principle is an essential obstacle to the ‘mass killing’ of people suffering from physical or mental ‘defects’. Only the sanctity principle, he argues, ‘can ensure that others see these lacks as reasons to help us rather than to destroy us’ (1991).

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights included all humans within its remit. Because every human has a life of innate and absolute value, no one is excluded: it is enough to simply be a member of the human species. The Preamble to the Universal Declaration states that the ‘recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace’ (UN, 1948). But where does this ‘inherent dignity’ come from? Why do humans possess inherent dignity, just by virtue of being human, while chimpanzees, for example, do not? No further explanation is given because, put simply, this is not susceptible to proof. As we saw in the previous section, there are no rational grounds for believing that there is an important moral difference between all humans and all animals. Rather, a belief in the unique specialness of humans can only be a matter of faith.

John Finnis attempts to answer this by saying that ‘one cannot reasonably affirm the equality of human beings, or the universality and binding force of human rights, unless one acknowledges that there is something about persons which distinguishes them radically from sub-rational creatures’ (2004: 4). But, as we saw in the previous section, not all humans are ‘distinguished radically’ from ‘sub-rational creatures’, rather, there are many human beings who are much more ‘sub-rational’ than the average chimpanzee.

Nussbaum goes to the heart of the problem here: she admits that the ‘rhetoric of human specialness has had its good role in history’, but ‘its flipside has been hideous moral obtuseness’ (2001: 1544). A belief in human specialness may have good consequences for humans—the rhetoric of human rights, for example, promotes equality and attempts to outlaw discrimination—but it has bad consequences for animals, and, importantly, it rests upon shaky empirical foundations. Empirically it is simply untrue to say that there is a sharp distinction between the capabilities of all human beings and those of animals.

Do we need to believe in the sanctity principle in order to condemn the Nazis’ lack of respect for the 6 million people who died in the Holocaust? In my view, we do not. A belief that killing is wrong because death causes very grave harm to the person who is killed would also lead us to condemn the Nazis’ appalling crimes in the strongest possible terms. Moreover, the Nazis did, in fact, believe in the sanctity of certain sorts of human life, but they drew a morally repugnant line between lives that were of value and lives that were not, based upon membership of racial, religious and other social groups. Robert Jay Lifton (2000) describes the process as ‘doubling’: many Nazi doctors carried out exceptionally cruel experiments on concentration camp victims while living ethically decent lives at home. Martha Nussbaum draws an analogy between this and our treatment of animals, which, she argues, ‘is, in disturbing ways, like the treatment of Jews in the Holocaust, particularly with respect to the capacity of normal, good people to rationalize and deny that suffering is taking place’ (2001: 1511).

Conor Gearty has persuasively argued that the term ‘human rights’ has come to signify compassion and active concern for others (2006: 43). According to Gearty, ‘the term “human rights” is the phrase we use when we are trying to describe decency in our post-philosophical word’ (2006: 56–7). It is undeniably true, as Gearty argues, that the notion of ‘human rights’ ‘can be made to do good work’ (2006: 56). Given that the ‘grip of decency on public affairs’ is precarious (2006: 92), Gearty maintains that the pragmatist should embrace the language of human rights and make it do its ‘good work’, rather than ‘wandering from the battlefield of meaning with intellectual purity intact but honour in shreds’ (2006: 56).

No one could argue with the importance of promoting decency and compassion, but Richard Rorty (1993) would contest Gearty's conclusion that this can be achieved by adopting the language of human rights. Rorty points out that rapists, torturers and ethnic cleansers could nevertheless believe in human rights and perpetrate their acts of subjugation and brutality with a clear conscience because they do not, in fact, regard their victims as fellow human beings. People who are prepared to inflict suffering on others and who ‘think of themselves as a being a certain good sort of human being—a sort defined by explicit opposition to a particularly bad sort’, will not necessarily be ‘cured’ and taught the values of decency and compassion by a human rights culture (Rorty, 1993: 126).

What is a person?

One way around the problem that there is not, in fact, anything empirically special about all human beings might be to contest the idea that existing as a person is coterminous with simply being alive and human. The qualities which are held up as justifications for marking humans out for special treatment are generally those associated with personhood, rather than with simply being a member of the human race. So, for example, it could be argued that an anencephalic neonate is undoubtedly alive, but will never become a person. At the other end of the lifespan, Tony Bland was alive but had permanently ceased to be a person.

This distinction is a familiar one to philosophers, but raises difficulties for lawyers, and for adherents of the sanctity principle. John Locke, for example, defined a person as ‘a thinking intelligent being that has reason and reflection and can consider itself as itself, the same thinking thing, in different times and places’ (Locke, 1690: ch. 9, para. 29). Joseph Fletcher laid out what he referred to as the ‘original indicators of humanhood’, a list of 15 characteristics which included criteria such as minimal intelligence, self-awareness and self-control (Fletcher, 1973). Jeff McMahan says that to be a person, ‘one must have the capacity for self-consciousness’ (2002: 6) and ‘a rich and complex mental life, a mental life of a high order of sophistication’ (2002: 45). Derek Parfit adopts a similar definition: ‘to be a person, a being must be self-conscious, aware of its identity, and its continued existence over time’ (1984: 202). Mary Anne Warren lays out five characteristics which ‘entitle an entity to be considered a person’ (1998 [1973]: 178). These are, ‘very roughly’:

Consciousness … and in particular the capacity to feel pain.

Reasoning (the developed capacity to solve new and relatively complex problems);

Self-motivated activity …

The capacity to communicate …

The presence of self-concepts, and self-awareness …

Warren's point is not that an entity must have all of these attributes to be properly considered a person, nor that any one of them is a necessary criterion of personhood, although she suggests that (1) and (2) ‘look like fairly good candidates for necessary conditions’. Rather, Warren's claim is that ‘any being which satisfies none of (1)–(5) is certainly not a person’ (1998 [1973]: 178). She:

… consider[s] this claim to be so obvious that … anyone who denied it, and claimed that a being which satisfied none of (1)–(5) was a person all the same, would thereby demonstrate that he had no notion at all of what a person is—perhaps because he had confused the concept of personhood with that of genetic humanity. (1998 [1973]: 178)

What is also important about this account of personhood is that it implies a gradualist approach to the question of when a person comes into existence and when she ceases to exist. But a gradualist approach to something as critical as the definition of a human person is an anathema to the law. For the purposes of law, a person's existence begins at the moment of birth, that is, when the child has an existence separate from her mother, and ends at death, which is defined as the death of the whole brain. These clear legal boundaries help us to answer questions about the legitimacy of abortion, for example, or cadaveric organ transplantion. But while bright-line boundaries between when a person exists and when they have ceased to exist might be helpful for the law, this is at the expense of a degree of artificiality and over-simplification, which is avoided by the more nuanced approach adopted by Parfit, McMahan, Warren and others.

The law struggles to know how to deal with human beings at the very margins of existence—such as anencephalic neonates and PVS patients—because, just like the sanctity principle, it accords them exactly the same status as a conscious, rational person. According to the sanctity principle, the life of a being that is alive and human is regarded as sacred, regardless of whether that life contains any of the goods of human existence. Deliberately bringing about the death of a human being who permanently lacks all of the attributes we associate with personhood is as contrary to the sanctity principle as the killing of a healthy person who wants to go on living.

Perhaps it would be better to admit that death involves two stages, death of the person and death of the human organism. Our minds, David DeGrazia explains, ‘are not identical to our organisms’ (DeGrazia, 2003: 437). It might then be possible to say that Tony Bland died as a person when he fell into a coma following the Hillsborough tragedy, and that he died as an organism nearly four years later, a few days after his doctors withdrew the ANH which was keeping him alive. An anencephalic baby is a live human organism, but it will never be a live human person. Once the person no longer exists, or where, in the case of an anencephalic baby, a person will never exist, their life is sacred only if we think that simply being a human organism gives it special status. This is plausible, I would argue, only as a matter of religious belief.

In the next section, I turn to the consequences this has for the wrongness of killing.

The wrongness of killing

The sanctity principle is often said to be behind our shared view that killing another person is very seriously wrong (McCall Smith, 1999). Dieter Giesen (1995: 204), for example, argues that any weakening in the censure of, and prohibition against killing will result in ‘a general moral decline’. It goes without saying that killing someone who wants to live must always be considered one of the most morally reprehensible actions it is possible to imagine. It deprives them of everything they currently value, and that they might value in the future, as well as robbing the people who love them of a person whose existence gives their life richness and meaning. There are, of course, times when the law will not categorize the killing of someone who wants to live as a crime, perhaps because the person was killed in self-defence. But that does not lessen the fact that the killing has deprived the dead person of everything that they value and that they might value in the future, and that this is a terrible thing to do to someone.

But this is a description of the wrongness of killing which focuses on the harm which it causes. Killing is normally a great wrong because dying is normally a very great harm (Hope, 2004). Killing is wrong instrumentally because it destroys everything that has been invested in the person's life, as well as depriving the person who is killed of all future experiences. David DeGrazia describes how an instrumental view of the wrongness of killing might explain why killing a human being is normally more wrong than killing a dog. Humans, so the argument goes, ‘typically have life plans, projects and deep personal relationships, all of which would be destroyed by untimely death’ (DeGrazia, 2002: 33). In contrast, ‘dogs have at most very truncated plans and, while they have relationships, they typically lack the depth and range that one finds in the typical human case’ (2002: 33). Death will usually therefore cause less harm to a dog than it does to a human being.

But while death is normally one of the worst things that can happen to a human being, this will not always be the case. Death does not harm an anencephalic infant, for example, because, as Jeff McMahan has explained, ‘it has no capacity for well-being at all’ (McMahan, 1996: 13). Life in a permanent vegetative state is, according to Jonathan Glover, ‘subjectively indistinguishable from death, and unlikely to be thought intrinsically preferable to it by people thinking of their own future’ (1977: 46). If someone is suffering unbearably, death can come as a relief. Anyone who has watched someone die slowly and painfully over a prolonged period of time knows that death, when it finally comes, has no longer become the worst thing that could happen to that person. Rather, because it puts an end to their terrible suffering, wanting someone to die can be compatible with feelings of tremendous love and compassion.

On an instrumental view of the wrongness of killing, death is usually the worst possible thing that can happen to a human being, and so killing a very grave wrong, but it is clear that this is not universally the case, and there are times when death is wished for, or even longed for. Death is an instrumental harm because it eliminates a person's future. In the vast majority of cases, that future is likely to contain positive and valuable experiences, as well as difficult and negative ones. Premature death is therefore a very great harm, and killing would be very seriously wrong. But where we can be certain that a human being's future contains no experiences at all, or only pain and suffering which has become unbearable, death may no longer be an instrumental harm.

An instrumental view of the wrongness of killing explains why, as Ronald Dworkin (1998) has pointed out, there is an important difference between a jilted teenager who feels suicidal, and someone in the final stages of motor neurone disease, who does not want to endure a painful and frightening death. Death would be a bad thing for the lovesick teenager because it is overwhelmingly likely that their life will contain future opportunities and experiences which they will be capable of valuing, once they have got over the undeniably painful trauma of being rejected by their first love. In contrast, for the person suffering from a terrible degenerative disease who knows that she has a few weeks to live, and that those weeks are going to be unbearably distressing, death may not only not be a bad thing, but might instead be desperately sought as a way to relieve imminent and intolerable suffering.

If someone does not want to live, and, on the contrary, desperately wants to be killed humanely in order to avoid the terrible suffering which they are currently enduring, or the distressing death which they know to be imminent, the sanctity principle insists that killing in such circumstances is just as wrong as when a person who wants to continue living is murdered. It converts the right to life into a duty to live, for those who are unable to take their own life. Dan Brock argues that ‘the right not to be killed, like other rights, should be waivable when the person makes a competent decision that continued life is no longer wanted or a good, but is instead worse than no further life at all’ (1992: 53). According to Brock, euthanasia is properly understood not as murder, but ‘as a case of a person having waived his or her right not to be killed’ (1992: 53). Michael Tooley makes a similar point; he suggests that ‘if an individual asks one to destroy something to which he has a right’—for example, his life—‘one does not violate his right to that thing if one proceeds to destroy it’ (1972: 207).

I am not sure I would go quite that far, however, because Brock and Tooley suggest that all that matters is the person's own view that their life has ceased to be of value to them. While this is important, the person who has been asked to do the killing has a moral responsibility to test for themselves whether death has now become the ‘lesser of two evils’, or put another way, whether causing the patient's death is compatible with her duty of care, and, in the case of incompetent patients, with her duty to act in their best interests. A doctor who gave a lethal injection to a lovesick teenager would not be acting properly because she would be ignoring the fundamental duties of a doctor. In the case of a patient with motor neurone disease who desperately does not want to suffer the distressing final days she knows to be imminent, medicalized killing could, I would argue, be compatible with the doctor's legal duty of care and with her ethical duties of non-maleficence and beneficence.

My contention here is that the degree to which an act of killing is wrong may, in certain circumstances, depend upon the extent to which death is a harm for the victim. McMahan explains this particularly elegantly:

if it is right that when we die we cease to exist, it seems to follow that death cannot be bad because of its intrinsic features in the way that, for example, suffering is. For non-existence has no intrinsic properties, positive or negative, it must instead be comparative. Death must be bad by comparison with what it excludes.… So to evaluate the badness of a particular death we must have some sense of the value of the life that is lost. A complete account of the badness of death must therefore incorporate an account of what it is for a life to go well or badly, what makes some lives better or more worth living than others, and so on. (2002: 98)

So in evaluating the badness of death, we can only make a judgement by comparing it with the alternative. Of course the alternative is not immortality, but dying at some point in the future. As David DeGrazia explains, because death is inevitable for all of us, ‘“life or death” choices are really “this death or that death” choices’ (2003: 33). We are therefore comparing two possible lives: the shorter life which results from death now and the longer life which would result if death were postponed (Feldman, 1992).

In the vast majority of cases, two related factors combine to ensure that continued life, and death at some point in the future, must be preferable to death now. First, for most people, including those suffering from terminal illnesses, continued life will contain both good and bad experiences. There will be very few cases in which it might be possible to be confident that death now has ceased to be a harm for the patient. Second, we are, of course, speculating about the sort of life that someone would have if death were postponed. As a result of this inherent uncertainty, it will again usually be impossible confidently to conclude that it would be better for someone to die now, rather than at some unspecified future time.

There are, however, some rare cases when we can predict the life that is lost by dying now, rather than at a later date, with considerable certainty, and be sure that it will not contain any of the goods of a normal human existence. For Tony Bland, the longer life which would result from postponing death would be of no value to him. Death, as the House of Lords admitted, was no longer bad for Tony Bland because he had ceased to have a life which he would ever be capable of valuing. Similarly, an anencephalic infant permanently lacks the capacity for consciousness, and their future life can contain no goods at all.

It seems clear—unless one subscribes to the view that, simply being alive and human is a good in its own right—that death was no longer a harm for Tony Bland. Might it, however, be possible to go further and say that death has become the best outcome for him? In some ways it might be argued that Tony Bland has ceased to have any interests at all, and so death is neither bad nor good for him. This was the view of Lord Keith in the House of Lords, who argued that ‘to an individual with no cognitive capacity whatever, and no prospect of ever recovering any such capacity in this world, it must be a matter of complete indifference whether he lives or dies’.

While Tony Bland clearly has no immediate interests in anything at all, there are those who would argue that we do, in fact, have interests which survive our permanent lack of consciousness and sentience. In the Court of Appeal in Bland, two of the judges, Sir Thomas Bingham MR and Hoffmann LJ (as they then were) appeared to adopt such a position, and maintained that, despite his condition, Tony Bland continued to have an interest in the manner of his death. Sir Thomas Bingham MR, for example, thought that Tony Bland retained an interest in putting ‘an end to the humiliation of his being and the distress of his family’. Similarly, Hoffmann LJ was of the view that:

It is demeaning to the human spirit to say that, being unconscious, he can have no interest in his personal privacy and dignity, in how he lives or dies. Anthony Bland therefore has a recognisable interest in the manner of his life and death.

Are Sir Thomas Bingham and Hoffmann LJ right that we retain an interest in how we die once we have lost the capacity to know anything about it? We do generally think that it is important to respect the wishes of those who will no longer know or care about whether those wishes are respected. They will not suffer distress or anguish if we ignore their clear and unambiguous advance directive, but most of us believe this would be the wrong thing to do.

I, for example, have a very strong preference not to be kept alive in a PVS and even though it would, when the time came, be a matter of ‘complete indifference’ to me whether that wish was respected, it would not be a matter of complete indifference to my friends and family, and it is important to me now to believe that my present wish to spare them the horror of watching me being kept alive in a PVS would be respected. While we cannot know for sure what Tony Bland himself thought about the manner of his death, since the prospect of permanently losing consciousness was surely the last thing on his mind when he set off for the FA cup semi-final in 1989, his father told the court that he was convinced that his son would not ‘want to be left like that’. If that was indeed his view, following it may or may not benefit Tony Bland but it does, perhaps, benefit all of us to know that, should we end up in a permanently comatose state, our desire to spare our families the prolonged ordeal of caring for us in a PVS would be respected. Analogously, in Ahsan v. University Hospitals Leicester NHS Trust [2006] Judge Hegarty QC was faced with the question of whether a woman in a PVS should be cared for at home by her devout Muslim family. The judge accepted that she would have no awareness of the presence of her family or of their prayers, and so could gain no solace or comfort from them; but he nevertheless concluded that:

… most reasonable people would expect, in the event of some catastrophe of that kind, that they would be cared for, as far as practicable, in a such a way as to ensure that they were treated with due regard for their personal dignity and with proper respect for their religious beliefs.

Regardless of whether Tony Bland had any interest in the manner of his death, the House of Lords were unanimously of the view that conduct which would cause death was compatible with the best interests test. Once it has been decided, as it must have been in Bland, that death had become an acceptable, if not the best outcome, then James Rachels would argue that ‘the usual reason for not wanting to be the cause of someone's death does not apply’ (Rachels, 1975: 79–80). If a doctor is content to cause death by withdrawing ventilation or ANH—through which the person might suffocate or starve to death—it seems odd that the law should forbid him from causing death more quickly, and perhaps more humanely. Simon Blackburn admits that drawing a distinction between treatment withdrawal and killing may salve some consciences, but he argues that ‘it is very doubtful whether it ought to, since it often condemns the subject to a painful, lingering death, fighting for breath or dying of thirst, while those who could do something stand aside, withholding a merciful death’ (Blackburn, 2001: 63).

The important question is surely whether death is a harm, not whether it is caused by killing or letting die. If death is a harm, and it invariably is, then both deliberate killing and the withdrawal of life-prolonging treatment would be wrong. Only where death is no longer a harm is the withdrawal of life-prolonging treatment plausibly in the patient's best interests. But where death is no longer a harm, killing too may, in certain circumstances, cease to be wrong, and may even be said to be in the patient's best interests, since it will bring about the same end result—death—but do so more quickly and humanely.

Conclusion

The conclusion I wish to draw here is that we should not shy away from admitting that there are times when death is no longer bad for a patient. Indeed I would go further and argue that, for some patients, it will occasionally be possible to conclude that the ‘balance sheet’ militates in favour of an earlier death. For Dianne Pretty, a woman who desperately wanted to be helped to die in order to avoid the sort of death which is commonly experienced by sufferers of motor neurone disease, the negative consequences of a longer life were clear: her imminent death was likely to be distressing and frightening.Footnote 6 What is especially interesting and, in my view, incoherent about the sanctity principle is that it works to suggest that an individual, such as Dianne Pretty, who had become firmly of the view that her life had ceased to be a benefit to her, and who—regardless of any feelings of ‘awe’ she may have had at human evolution or creation—clearly believed that dying now had become better for her than dying later, nevertheless had to endure the later and more distressing death because of other people's view that her life continued to be sacred. I would agree with Jonathan Glover that the views of the person whose life it is as to whether their life is worth living is evidence of an ‘overwhelmingly powerful kind’, which only a ‘monster of self-confidence’ would ignore (1977: 54).

If we admit that there are cases in which death might be preferable to the alternative, we are surely under a duty to achieve the best outcome for the patient in the most humane way. Yet the law prohibits this, because of an, in my view, irrational commitment to the idea that there is something sacred about simply being alive and human. It was possible to achieve Tony Bland's death, but only by ‘semantic sleight of hand’ (Kennedy, 1991): treatment which was necessary to prolong his life had become futile and could be withdrawn. This led to Tony Bland's slow death from dehydration and starvation, which his family had to witness over the course of several days. Patients, I would argue, often die worse deaths than they would if the sanctity principle relinquished its grip on the law's approach to end-of-life decision-making.

Of course my opponents will point to the dangers of the slippery slope, and of unwanted deaths being forced upon vulnerable and dependent individuals. But my point is that it is only possible to conclude that death is a good thing for a person if we can be certain that it would be better for them if they died now, and that this would be consistent with their wishes and values. This will very seldom be the case. It is also of critical importance to remember that the courts already feel confident in making such judgements when death can be achieved by treatment withdrawal. If we can confidently conclude that death now as opposed to death later is preferable for a patient—either by applying the best interests test for an incompetent patient, or by respecting the competent patient's own choice about whether their life is worth living—where it can be achieved by treatment withdrawal, it seems odd that we cannot make the same assessment when a positive act is necessary to achieve death.

As we saw at the outset, the courts have sanctioned conduct which led to the deaths of baby J and Tony Bland. Presumably, then, they felt sufficiently certain that J was suffering intolerably and that Tony Bland was permanently unable to benefit from his existence. Whether the court is able to judge these factors with the requisite degree of certainty does not, in my view, depend on the incidental presence of a gastrostomy tube or a mechanical ventilator. The sanctity principle thus elevates a simple medical fact about the nature of the person's condition into a critical moral distinction. The decision whether someone's life should be brought to an end is thus made on irrelevant grounds (Rachels, 1975). This decision should be based on an assessment of whether death is now the best option for a patient, rather than on whether they happen to require ANH or ventilation.

Obviously, people disagree over what a good death consists in. Some people, perhaps as a result of their religious beliefs, would regard a death brought about by lethal injection as worse than any other. This point of view should, of course, be respected. Medicalized killing should never be forced upon anyone against their wishes, and a conscientious objection clause would be essential. For many of us, however, a quick death, perhaps in the presence of people we love, would be better than being allowed to die slowly over a period of days or weeks. As one patient who had sought access to physician assisted suicide in Oregon put it: ‘I want to do it on my terms. I want to choose the place and time. I want my friends to be there. And I don't want to linger and dwindle and rot in front of myself’ (Ganzini et al., 2003: 384). The important point here is that even when a lethal injection would produce a death which an individual would find infinitely preferable to a ‘natural’ death, or one induced by the withdrawal of treatment, the sanctity principle's influence over the law ensures that only these more prolonged and distressing deaths are lawful. I cannot improve upon James Rachels’ stark condemnation of the consequences which flow, at least in part, from the law's continued adherence to the sanctity principle:

The doctrine that says that a baby may be allowed to dehydrate and wither, but may not be given an injection that would end his life without suffering, seems so patently cruel as to require no further refutation. (Rachels, 1975: 79)

Notes

1 It should be noted that not everyone would accept this definition. Christine Korsgaard (1983), for example argues that intrinsic value must be contrasted with extrinsic not instrumental value.

2 Because the person who dies is already extremely ill, it may be difficult to establish whether their death was caused by the doctor's actions or by their pre-existing illness. See, for example, R v. Cox [1986].

3 See also the comments of Sir Stephen Brown P in Re H (adult: incompetent) [1998]: ‘The sanctity of life is of vital importance. It is not, however, paramount.’

4 Citations from court cases are from online resources such as Lexis and therefore do not have page numbers.

5 Richard Ryder has said: ‘The word speciesism came to me while I was lying in a bath in Oxford some 35 years ago. It was like racism or sexism—a prejudice based upon morally irrelevant physical differences’ (Ryder, 2005).

6 Mrs Pretty was unsuccessful in her application for judicial review of the DPP's refusal to provide an undertaking that he would not prosecute her husband, Mr Pretty, under section 2 of the Suicide Act 1961 if he helped his wife to die. R (on the application of Pretty) v. Director of Public Prosecutions [2002].

References

Blackburn S. (2001). Ethics. Oxford: Oxford UP.

Brierly M. (2006). Public life and the place of the Church: Reflections to honour the Bishop of Oxford. Dartford: Ashgate.

Brock D. (1992). Voluntary active euthanasia. Hastings Center Report, 22, 10–22.

Coggan J. (2007). Ignoring the moral and political shape of the law after Bland: The unintended side-effect of a sorry compromise. Legal Studies, 27, 110–125.

Cohen C. (1986). The case for the use of animals in biomedical research. New England Journal of Medicine, 315(14), 865–870.

Cooperman A. (2002). Two Jewish groups back therapeutic cloning: Orthodox leaders break with right. Washington Post, 13 March, A4.

DeGrazia D. (2002). Animal rights. Oxford: Oxford UP.

DeGrazia D. (2003). Identity, killing and the boundaries of our existence. Philosophy and Public Affairs, 31, 413–442.

Dorff E.N. (2002). Embryonic stem cell research: The Jewish perspective. United Synagogue Review, spring, 29–33.

Dworkin R. (1998). Euthanasia, morality and law. Loyola of Los Angeles Law Review, 31, 1147.

Dworkin R. (1992). Unenumerated rights: Whether and how Roe should be overruled. University of Chicago Law Review, 59, 381–432.

Dworkin R. (1993). Life's dominion: An Argument about abortion and euthanasia. London: HarperCollins.

Cox M. (1978). Animal liberation: A critique. Ethics, 88(2), 106–118.

Feldman F. (1992). Confrontations with the reaper. Oxford: Oxford UP.

Finnis J. (2004). Natural law: The classical tradition. In Coleman J., Shapiro S. and Himma K.E. (Eds), The Oxford handbook of jurisprudence and philosophy of law, pp. 1–60. Oxford: Oxford UP.

Fletcher J. (1973). Medicine and the nature of man. Science, Medicine and Man, 1, 93–102.

Frey R.G. (1996). Medicine, animal experimentation, and the moral problem of unfortunate humans. Social Philosophy and Policy, 12, 181–211.

Friedman L. (1994). Is there a modern legal culture? Ratio Juris, 7, 117.

Ganzini L., Dobscha S.K., Heintz R.T., & Press N. (2003). Oregon physicians’ perceptions of patients who request assisted suicide and their families. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 6, 381–390.

Gearty C. (2006). Can human rights survive? Cambridge: Cambridge UP.

Giesen D. (1995). Dilemmas at life's end: A comparative legal perspective. In Keown J. (Ed.), Euthanasia examined. Cambridge: Cambridge UP.

Glover J. (1977). Causing death and saving lives. London: Penguin.

Goodall J. (1991). Through a window: My thirty years with the chimpanzees of Gombe. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

Gray J. (2002). Straw dogs: Thoughts on humans and other animals. London: Granta.

Hope T. (2004). Medical ethics: A very short introduction. Oxford: Oxford UP.

Hughes J. (1998). Xenografting: Ethical issues. Journal of Medical Ethics, 24, 18–24.

Jackson E. (2004). Whose death is it anyway? Euthanasia and the medical profession. Current Legal Problems, 57, 415–442.

Kamm F.M. (2001). Ronald Dworkin on abortion and assisted suicide. Journal of Ethics, 5, 221–240.

Kennedy I. (1991). Treat me right. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Keown J. (2006). Restoring the sanctity of life and replacing the caricature: A reply to David Price. Legal Studies, 26, 109–119

Korsgaard C. (1983). Two distinctions in goodness. Philosophical Review, 92, 169–195.

Lifton R.J. (2000). The Nazi doctors: Medical killing and the psychology of genocide. New York: Basic Books.

Locke J. (1690). Essay on human understanding. Book II. London: Eliz Holt.

Mahoney J. (2006). The challenge of human rights. Oxford: Blackwell.

McCall Smith A. (1999). Euthanasia: The strengths of the middle ground. Medical Law Review, 7, 194–207.

McGee A. (2005). Finding a way through the ethical and legal maze: Withdrawal of medical treatment and euthanasia. Medical Law Review, 13(3), 357–385.

McMahan J. (1996). Cognitive disability, misfortune and justice. Philosophy and Public Affairs, 13, 3–35.

McMahan J. (2002). The ethics of killing: Problems at the margins of life. Oxford: Oxford UP.

Ministry of Justice. (2007). Mental Capacity Act Code of Practice. London: Ministry of Justice.

Naffine N. (unpublished). Law and the meaning of life. Unpublished manuscript.

Nussbaum M. (2001). Animal rights: The need for a theoretical basis. Harvard Law Review, 114, 1506–1549.

Nussbaum M. (2006). Frontiers of justice: Disability, nationality, species membership. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP.

Parfit D. (1984). Reasons and persons. Oxford: Oxford UP.

Patterson F., & Linden E. (1982). The education of Koko. London: Andre Deutsch.

Rachels J. (1975). Active and passive euthanasia. New England Journal of Medicine, 292(2), 79–80.

Rachels J. (1991). Created from animals: The moral implications of Darwinism. Oxford: Oxford UP.

Rorty R. (1993). Human rights, rationality and sentimentality. In Shute S., & Hurley S. (Eds.), On human rights: The Oxford Amnesty lectures 1993, 111–134. New York: Basic Books.

Ryder R. (2005). All beings that feel pain deserve human rights. The Guardian, 6 August.

Schweitzer A. (1929). Civilization and ethics: The philosophy of civilization. London: A&C Black.

Singer P. (1989). All animals are equal. In Regan T. and Singer P. (Eds), Animal rights and human obligations, 2nd edn. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Singer P. (1994). Rethinking life and death: The collapse of our traditional ethics. Oxford: Oxford UP.

Stith R. (1991). The right to death. New York Review of Books, 38(6), 28 March. URL (accessed April 2008): www.nybooks.com/articles/3322

Tooley M. (1972). Abortion and infanticide. Philosophy and Public Affairs, 2, 29–65.

United Nations (1948) Universal Declaration of Human Rights. URL (accessed April 2008): www.unhchr.ch/udhr/

Warren M.A. (1997). Moral status: Obligations to persons and other living things. Oxford: Oxford UP.

Warren M.A. (1998 [1973]). On the moral and legal status of abortion. In Pence G.E. (Ed.), Classic Works in Medical Ethics, 169–182. Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill.

Wise S. (2001). Rattling the cage. New York: Perseus Publishing.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Alasdair Cochrane, Conor Gearty and Nicola Lacey, and to the participants at a BIOS Research Seminar, for their comments on an earlier draft of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Cases cited

Cases cited

Ahsan v. University Hospitals Leicester NHS Trust [2006] EWHC 2624.

Airedale NHS Trust v. Bland [1993] AC 789.

Pretty v. UK (2002) 35 EHRR 1.

R (on the application of Pretty) v. Director of Public Prosecutions [2002] 1 AC 800.

R v. Cox [1986] The Times, 30 December.

Re H (adult: incompetent) [1998] 2 FLR 36.

Re J (Wardship: Medical Treatment) [1991] 2 WLR 140.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jackson, E. Secularism, Sanctity and the Wrongness of Killing. BioSocieties 3, 125–145 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1017/S1745855208006066

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1745855208006066