Introduction

Dementia at any age brings many challenges into one's life, such as coping with the diagnosis (e.g. Johannessen et al., Reference Johannessen, Engedal, Haugen, Dourado and Thorsen2019), finding ways to connect with others (e.g. Nilsson, Reference Nilsson2017) and managing stigma (e.g. Patterson et al., Reference Patterson, Clarke, Wolverson and Moniz-Cook2018). People who develop early onset dementia, typically classified as before the age of 65 (Miyoshi, Reference Miyoshi2009), often face additional distinctive challenges, including changes in work, family relationships, self-esteem, loss or lack of meaningful occupation, and feelings of social isolation and dependency (Harris, Reference Harris2004). Understanding the different factors that contribute to living well with early onset or ‘working-age’ dementia is therefore highly important.

Acknowledging the strengths and positive experiences of people living with dementia is as important as recognising the adversities and sources of distress in their lives (Wolverson et al., Reference Wolverson, Clarke and Moniz-Cook2016; McParland et al., Reference McParland, Kelly and Innes2017). Recent findings highlight the role of positive psychological resources, such as self-efficacy, optimism and self-esteem for living well with dementia (e.g. Lamont et al., Reference Lamont, Nelis, Quinn, Martyr, Rippon, Kopelman, Hindle, Jones, Litherland and Clare2020). Clare et al. (Reference Clare, Wu, Jones, Victor, Nelis, Martyr, Quinn, Litherland, Pickett, Hindle, Jones, Knapp, Kopelman, Morris, Rusted, Thom, Lamont, Henderson, Rippon, Hillman and Matthews2019) noted that in addition to these highly influential psychological factors, it is important to identify the contribution of different kinds of physical resources (e.g. sleep and subjective health), as well as social and environmental resources (e.g. social networks and status in community) to reach a more comprehensive picture. For example, while a higher number of needs and mental health challenges are associated with lower quality of life (Millenaar et al., Reference Millenaar, Hvidsten, de Vugt, Engedal, Selbæk, Wyller, Johannessen, Haugen, Bakker, van Vliet, Koopmans, Verhey and Kersten2017), factors reflecting functional ability and social resources are associated with better quality of life of individuals living with dementia (Martyr et al., Reference Martyr, Nelis, Quinn, Wu, Lamont, Henderson, Clarke, Hindle, Thom, Jones, Morris, Rusted, Victor and Clare2018).

Both having other people's support (Mayrhofer et al., Reference Mayrhofer, Shora, Tibbs, Russell, Littlechild and Goodmanin press) and sense of agency (Clemerson et al., Reference Clemerson, Walsh and Isaac2014) have been shown to play an important role in living positively with early onset dementia. Clemerson et al. (Reference Clemerson, Walsh and Isaac2014) found that making decisions concerning their life enabled their participants with early onset dementia to regain a sense of agency. The importance of access to services also has been identified (Mayrhofer et al., Reference Mayrhofer, Mathie, McKeown, Bunn and Goodman2018); in the case of younger people living with dementia, this requires specialised services that complement their particular needs and contexts. Earlier qualitative research into the employment-related experiences of people living with dementia indicate that for some, continuing work is possible, while for others stopping work is the best way to preserve their health and wellbeing (Ritchie et al., Reference Ritchie, Tolson and Danson2018). However, poor treatment, scarce support and lack of input in decisions about continuing work or leaving employment may have the opposite effect on an individual's wellbeing (Chaplin and Davidson, Reference Chaplin and Davidson2016; Ritchie et al., Reference Ritchie, Tolson and Danson2018). Thus, a need exists to explore experiences of working-age people living with dementia from the perspective of realisation of their right to autonomy and participation (cf. Egdell et al., Reference Egdell, Stavert and McGregor2018). Specifically, if we are to recognise the views, preferences and life situations of people living with dementia when supporting access to their rights, then we must pay careful attention to the different meanings they ascribe to such rights (Wolfe et al., Reference Wolfe, Greenhill, Butchard and Day2020).

The aim of this inter-disciplinary study is to explore how working-age people living with dementia seek to influence their lives, and what makes it easier or more difficult for them in their everyday life. The study combines social psychological and legal viewpoints to understand experiences related to making decisions and choices regarding one's life and can, thereby, be positioned in the tradition of socio-legal research (McConville and Chui, Reference McConville, Chui, McConville and Chui2017).

Theoretical insights for the study were drawn from relational conceptualisations of autonomy (e.g. Barclay, Reference Barclay, Mackenzie and Stoljar2000; Harding, Reference Harding, Foster, Herring and Doron2014); by placing individual experiences in their social context (Delamater et al., Reference Delamater, Myers and Collett2015), we attempt to understand how different resources and impediments shape the ways in which working-age people living with dementia seek and manage to influence their lives. Given that, it is also crucial to understand the role that access to participation plays in ensuring that meaningful options and resources are available to them to fashion their lives in accordance with their aims and wishes.

Autonomy as a relational phenomenon

The term ‘relational autonomy’ can be seen as referring to a range of perspectives that all address the social embeddedness of individuals from various standpoints (Mackenzie and Stoljar, Reference Mackenzie, Stoljar, Mackenzie and Stoljar2000). How agents relate to social structures and consequently, for example, the degree to which they can affect their circumstances and the course of their experiences, remain a matter on which theorists hold differing views (see e.g. Barclay, Reference Barclay, Mackenzie and Stoljar2000).

In the present study, we understand agents’ ability to influence their lives as shaped in co-action with other people (Gergen, Reference Gergen2009), as well as in interaction with the wider social context such as material and discursive conditions. By material conditions we refer, for example, to living conditions and access to health care, information, communication and services (cf. Rao and Min, Reference Rao and Min2018). Discursive conditions in turn embrace prevailing norms and discourses (Showden, Reference Showden2011) circulated through and modified in social interaction, and various kinds of cultural resources such as knowledge and media representations (Layder, Reference Layder2006: 281). Norms and discourses reflect our societal values and expectations which self-reflexive individuals can, however, negotiate and respond to in varying ways (e.g. Barclay, Reference Barclay, Mackenzie and Stoljar2000). Next, we will consider these interpersonal, material and discursive aspects from the perspective of legal principles.

In jurisprudence, autonomy is seen as the core principle underpinning human and fundamental rights discourses. Liberalism views autonomy as a sphere of personal freedom wherein individuals may shape their lives according to their own distinctive personalities (Raz, Reference Raz1986). This account of autonomy assumes that to be recognised as autonomous, a person must be capable of making rational decisions; the rational person has the capacity to understand the difference between right and wrong and to bear the consequences of unwise decisions (Dworkin, Reference Dworkin1993). This approach can be defined by entertaining the so-called individual (or traditional) ideal of autonomy. A differing perspective is relational autonomy put forward by relational theorists arguing that instead of considering adults with capacity as atomistic individuals, we should consider autonomy through relationships with other people (Nedelsky, Reference Nedelsky1989). Thus, people in close relationships seek to compromise in their decision-making by trying to make a decision according to what is good for ‘us’ rather than what is best for ‘me’. The goal of relational autonomy is thus to build up relationships that enhance people's lives rather than seeking to maximise individual freedom (Herring, Reference Herring2013).

Relational autonomy also highlights the importance of supporting people's relationships in order to support their autonomy. For instance, when decisions need to be made for a person of doubtful capacity, decisions should be made within the person's relational context. In some cases, involving family members and care-givers in decision-making will enable an individual to have the capacity to make a decision they otherwise would not have (Herring, Reference Herring2013).

In addition to intimate relations, attention has also been paid on other aspects, such as how the law responds to relational people through attentiveness to the relationships and broader context that shape people's experiences and situations. According to Harding (Reference Harding, Foster, Herring and Doron2014), by being attentive to relational selves and relational law, relational life, i.e. interpersonal and institutional interconnections that shape our everyday existence, can be better understood and more appropriately regulated.

There are also written legislation and regulations that establish the importance of respecting a person's autonomy. For instance, according to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD), right to autonomy is explicitly expressed in Article 3(a) where it is stated that respect for inherent dignity, individual autonomy, including the freedom to make one's own choices, and independence of persons are principles of the Convention. Furthermore, in Article 12 autonomy is expressed implicitly. According to Article 12(3), states parties shall take appropriate measures to provide access by persons with disabilities to the support they may require in exercising their legal capacity. Article 12 is an example about relational regulation taking account of the relationships of support. Thus, it is not surprising that in connection with Article 12, new approaches have been developed from the point of view of relational autonomy (e.g. Series, Reference Series2015).

The concept of participation can be viewed both from a broader societal perspective and as an individual right in one's own case. From the perspective of human rights, participation highlights inclusion, non-discrimination and equality, and draws attention to participation as a form of empowerment, self-worth and autonomy (e.g. Secker, Reference Secker2009). From the point of view of people living with dementia, this requires shifting the focus from deficits to repositioning them as active citizens within their communities (Birt et al., Reference Birt, Poland, Csipke and Charlesworth2017; Nedlund et al., Reference Nedlund, Bartlett, Clarke, Nedlund, Bartlett and Clarke2019). The World Health Organization (2015) has highlighted that people living with dementia have the right to participate in society, and should also be empowered to participate in decision-making processes and to maintain their legal capacity. When people participate in a decision-making process, they do not necessarily make a decision by themselves, but are involved and listened to and their views are taken into consideration. Thus, the aim is to give some weight to a person's own views and values. One might thus say that when granted a right to participate, a person is not necessarily granted the right to master the question at hand, but rather to be a member of a team making decisions that concern them (Harding, Reference Harding2012; Mäki-Petäjä-Leinonen, Reference Mäki-Petäjä-Leinonen, Griffiths, Mustasaari and Mäki-Petäjä-Leinonen2017). In general, the theoretical discussion of participation has highlighted the process of participation and its connections to power, namely the significant role of equal power positions in decision-making processes (Carpentier, Reference Carpentier2015).

From the point of view of participation, the right to receive proper guidance and counselling is also important. According to the European Social Charter, the states parties should undertake the necessary measures to provide guidance, education and vocational training to persons with disabilities to ensure possibility for them to exercise effectively the right to independence, social integration and participation in the life of the community (Article 15). In Finland this is regulated by the Social Welfare Act (1301/2014) as well as other statutes. According to the Act, residents of each municipality must have access to social welfare guidance and counselling. Particular attention must be paid to guidance and counselling for children, young people and people with special needs (Section 6).

To conclude, in order to choose from different options and fashion their lives in accordance with their aims and wishes, individuals need conditions that enable them to do so (Showden, Reference Showden2011), such as conditions that guarantee their access to participation. Despite being attentive to the role of conditions, it is highly important to keep in mind that people living with dementia are not passive recipients of support but are individual persons and actors in society with their own abilities, interests and rights (Nedlund et al., Reference Nedlund, Bartlett, Clarke, Nedlund, Bartlett and Clarke2019). Against this background, a concept of autonomy that acknowledges both social influence and an individual's capability to reflect critically on and respond to it in different ways (Barclay, Reference Barclay, Mackenzie and Stoljar2000; Showden, Reference Showden2011) serves the best the aim of this study, which is to gain an understanding of how working-age people living with dementia seek to influence their lives, and what makes it easier or more difficult for them in their everyday life.

Methods

According to Choi and Pak (Reference Choi and Pak2006: 351), the goal of inter-disciplinarity is to ‘analyse, synthesise, and harmonise links between disciplines into a coordinated and coherent whole’. To address the aim of the present study, we pursued a reciprocal interaction between different disciplines (social psychology and jurisprudence) throughout the whole research process, from data collection to the analysis and formulation of results (Huutoniemi et al., Reference Huutoniemi, Klein, Bruun and Hukkinen2010). This study is part of an international multi-disciplinary research project scrutinising what happens when people develop dementia while still working.

Participants

Participants were recruited from local branch associations of the Alzheimer Society of Finland. The participants were visitors at two different associations located in two large cities, one in the southern region and one in the northern part of Finland. The data consist of three focus group discussions. The first group consisted of six participants, the second consisted of three and the third consisted of four. One male participant from the first group proved in the end not to have received a dementia diagnosis; thus, we excluded his accounts from this study. The remaining 12 participants had developed dementia while still working and were retired at the time of participating. Demographics of the participants are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Demographic data of the 12 participants

Materials

The topic guide was developed in collaboration between the members of our Finnish multi-disciplinary research team. The topic guide included questions such as: ‘What is it like to receive such a diagnosis while still working?’; ‘(How) did your situation at work and your working life change?’; ‘What kinds of information and support have you received?’; ‘What was your experience of the realisation of your legal rights?’; ‘What has or has not been helpful for you?’; ‘What kind of advice would you give to people in a similar situation?’; ‘What was it like to take part in the discussion?’; and finally, ‘Is there something you would like to add?’ The purpose of the group discussions was to reach each participant's unique experiences as well as shared experiences (Fern, Reference Fern2001). Shared experiences can give insight into group norms and meanings applied and shaped in discussion between participants recruited from pre-existing social groups (Bloor et al., Reference Bloor, Frankland, Thomas and Robson2001), in this case, working-age people with dementia who participated regularly in the activities provided by their local branch associations of the Alzheimer Society of Finland.

Procedure

Data collection took place between February and June 2019 at facilities provided by the local Alzheimer Society branches. Each group discussion was facilitated by two researchers from different disciplines, one with a background in psychology or social psychology and the other with a legal background. The second and third authors ran two of the groups, while the third group was facilitated by the first and second authors. Each group followed a similar format. The discussions were semi-structured using the topics described above. Follow-up questions were asked to elicit further information or clarification as needed. All participants contributed their perspectives to the discussions. The discussions lasted between 56 and 90 minutes. The discussions were audio recorded and the recordings were transcribed verbatim.

Ethical considerations

The participants were recruited in collaboration with employees of local branch associations of the Alzheimer Society of Finland. They were informed, both in writing and orally, about the purpose and procedures of the study and asked to sign informed consent forms before the focus group discussion started. The voluntary nature of participation was emphasised throughout the process. The participants were encouraged to share their experiences in the group; however, they were given the option to simply listen if they were not willing to share their thoughts. The group discussions enabled individuals living with cognitive impairment to participate in the study in small groups and with people they already knew from the activities provided by the associations (see also e.g. Brorsson et al., Reference Brorsson, Öhman, Lundberg and Nygård2016). At the same time, this approach enables participants to speak for themselves or abstain, which supports the ethical principle of avoiding harm by allowing people to engage how as they deem appropriate. The participants’ privacy was protected by storing and handling the data in a secure manner and by removing any identifying information from the data.

Data analysis

Theory-guided content analysis combining inductive and deductive approaches (Hsieh and Shannon, Reference Hsieh and Shannon2005) was used to organise and interpret the data. In the first phase, the first author, whose disciplinary background is in social psychology, read each focus group discussion through to gain an overview of the data and assign preliminary codes to passages of text that might be important from the perspective of influencing one's life (symptoms of cognitive impairment, stigma, social support, thinking positively, etc.). The second author, whose disciplinary background is in law, coded each discussion for autonomy (making one's own choices or e.g. plans for future) and participation (both from a broader societal and from an individual perspective). After that, they discussed the coding process. The main purpose of this discussion was to make sure that the first author would recognise accounts which were relevant also from the perspective of one's rights. Based on this, she refined the coding frame and subsequently examined the excerpts classified into each category more closely to identify, in particular, how surrounding conditions shaped one's access to autonomy and participation. Careful attention was paid also to how the participants reflected on these conditions to make sense of what is, or would be, the best option for themselves. Finally, the accounts were grouped into three themes and related resources and impediments for influencing one's life. Co-authors provided input to the approach and writing process, including suggesting improvements.

Results

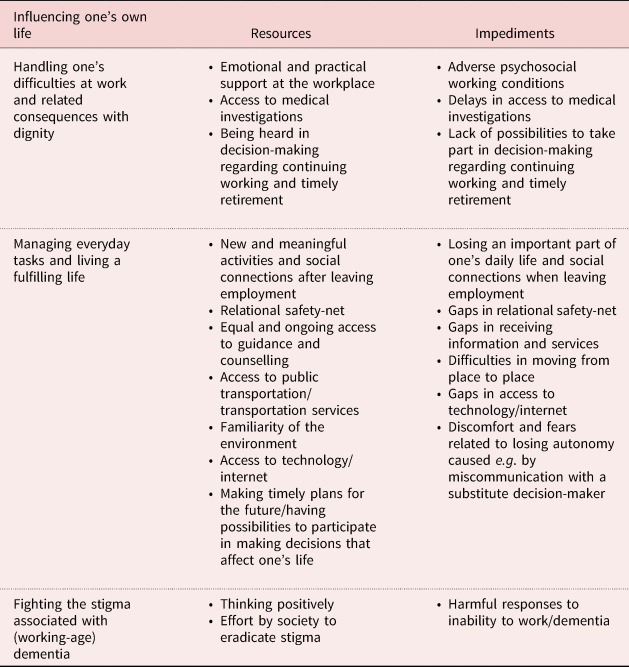

The information produced by the content analysis was used to construct three themes that elucidate the main ways in which the participants sought to influence their lives, and what made it easier or more difficult for them in their everyday life. Here we first present experiences related to these three themes, ranging from the time of working to living with dementia after receiving the diagnosis and leaving employment, and then draw the results together in Table 2 from the perspective of different resources and impediments for influencing one's own life. All personal names are replaced by pseudonyms.

Table 2. Resources and impediments for influencing one's own life when living with working-age dementia

Theme 1: Handling one's difficulties at work and related consequences with dignity

According to earlier research, people who develop dementia while still employed may struggle with problems at work, such as remembering tasks and difficulties in adjusting to new tasks (e.g. Chaplin and Davidson, Reference Chaplin and Davidson2016). Challenges experienced at work, along with adverse interpretations of these difficulties, caused distress to many participants in this study. The ways in which dementia manifested itself at work included problems with remembering, not managing things as well as before, and feeling irritated, anxious or fatigued. Senni, for example, who reported having been ‘a happy and laughing’ person, found that some changes at her work were too challenging with her health condition. These work changes involved increased workload after staff reductions and especially expectations that she would manage and learn new things about technology. Senni shared that she became an ‘angry’ person after turning from an independent and competent employee into one who needed to rely on and ‘bother’ others (her words). Helpful and understanding colleagues, however, made the situation at least a little bit easier for her:

Of course when I didn't manage, and I always have been like that, you need to know how to do those things and you need to stay on top of things, and then suddenly you are in a situation in which you kind of have to ask from others and be at their mercy. But I had such wonderful colleagues who helped me, but I was ashamed indeed that I had to bother them a lot.

Several people shared that a loved one, colleague or boss was the one who suspected or raised concerns that something might be wrong. People who paid attention and brought up their concerns with the individual often played a key role in guiding them to health care. The importance of being taken seriously regarding the changes they were experiencing or the meaning of a boss's or colleagues’ communicative or empathetic responses was mentioned by many participants. The situation was rather different for those whose employer or working environment changed frequently or who worked independently, e.g. performing freelance work. Lack of close and long-term relationships at a workplace may create conditions in which there is no one to notice the difficulties an individual is having, as was the case for Jaakko: ‘probably no one noticed that there was a glitch when everyone was doing their own job, one made this and the other one that’.

Sometimes people reported that difficulties at work had initially been interpreted as signs of laziness, incompetence or alcoholism. Jaana said that she almost lost her job even though she tried to improve her performance. She was deeply offended when the first place her boss took her was an Alcoholics Anonymous Clinic instead of health care:

Yeah, they also tried to tell me that I'm an alcoholic, I'm tired, but that disease was making me tired. And that work was overwhelming already, how you say it.

A wrong interpretation may thus lead to experiences of being treated unfairly and disbelieved:

Virpi: I think it's the rudest thing to say that you are lazy, and then all the time you [are] try[ing] to do [your job].

Jaana: And you are slow.

Outi: Or that you are lying, as that boss said to me. It really was a shocking thing.

Almost all participants had stopped working immediately after receiving their diagnosis. The majority said that they had retired ‘quite willingly’ or were happy with this decision because the expectations related to their job description were too high or their job too fast-paced for someone in their situation. Furthermore, continuing might have been far too risky for themselves and others, as pointed out by Tuomo, who worked in the construction business. He decided to quit his job and go to see a doctor after experiencing ‘a close call’. For Tuomo, quitting ‘voluntarily’ and seeking medical advice seems to have been a way of staying in charge of his own situation and making a rational decision given the circumstances. Senni again pondered how workforce reductions and increasing demands to learn new tasks and technologies in her job caused too much ‘stress’. Although she was ‘relieved’ when her work ended, it was important for her to be able to influence the schedule for leaving on sick-leave:

All the time we only sat in different kinds of meetings and then the [workplace] doctor said that now [it is time for] you [to] leave, and then I was like, will you give me one week mercy.

As the human rights discourse highlights, people with disabilities have the right to participate in all aspects of life. For instance, working-age disability should not automatically lead to retirement. According to the UNCRPD, the parties must provide legislation to ensure that reasonable accommodations are made in the workplace for people with disabilities (Article 27). In Finland, it is stated in the Equality Act (3125/2014) that the employer shall make appropriate and reasonable accommodations to enable disabled persons to perform their duties (Article 15).

Sometimes the reasons for not exploring the possibilities to make accommodations for the individual were unclear, or the termination of employment came as a surprise, as was the case for Jaakko: ‘I did think then that I could, it came as a surprise, I could have continued working.’ Some adjustments had been made before Laura retired, but she felt distressed and fatigue prevented her from going to work. Laura realised that she must leave her job when her child started to react negatively to the situation: ‘I can be nuts, but she does not have to be nuts. That much of my head worked.’ Laura's account is a vivid description of the relational context in which Laura strives for influencing her life.

Prior research has highlighted the importance of early identification of dementia to manage problems at work, the implementation of reasonable adjustments to enable the individual to continue working if he or she wishes to do so, and increased workplace awareness and knowledge (Thomson et al., Reference Thomson, Stanyon, Dening, Heron and Griffiths2019). Training interventions for employers have been suggested to help them recognise and respect the legal rights of employees with dementia (Egdell et al., Reference Egdell, Cook, Stavert, Ritchie, Tolson and Danson2019). Our participants’ experiences illustrate overall how important it is for an individual to have the opportunity to play a key role in the process of addressing challenges at work and to be given the opportunity to handle related consequences with dignity.

Theme 2: Managing everyday tasks and living a fulfilling life

Receiving the diagnosis could be ‘a relief’ when living with ‘uncertainty’ finally ended and one's own suspicions were proven right. However, often it was described as a ‘a big hit’ or ‘a shock’. The following dialogue shows how becoming ill may have a debilitating impact on mental wellbeing, sometimes to the extent that the person questions their willingness to keep living:

Virpi: I wouldn't have survived otherwise [without home care service and sister]. I probably would have put a bullet in my head if I had known how to shoot.

Outi: It has indeed been in my mind a few times also.

Jaana: There have been some suicidal thoughts.

Outi: I still have. This isn't any fun.

Jaana: We will rise from this. The crying helped then.

The participants described how different kinds of social and material resources helped them to manage everyday tasks and live a fulfilling life after receiving the diagnosis and leaving employment. However, they also reported the challenges they faced in relation to these resources.

Social relations and meaningful activities

Kimmo and several others said that losing both daily routines and social contacts from the workplace is a challenging situation: ‘I did feel a little bit bad. You had to give up friends and everything.’ The participants noted the meaning of different types of social relations that were valuable to them not only in themselves, but also as a source of emotional and practical support. All three focus groups emphasised the importance of doing things together and sharing thoughts in the Alzheimer Society's groups – people with whom they can be themselves and who understand with just ‘half a word’:

Paula: …this is a rescue.

Arja: Yes, it is.

Paula: This is really good, and you don't want to stay away, everybody is in the same boat, even if the disease would be a bit different, but still.

However, finding one's way to this kind of group may take time. Paula reported that she needed time to consider before she was ready to take part. Virpi again said that it was a good thing that her sister acted as her escort when she visited the association for the first time because she felt ‘terrified’ and would not have gone there alone. The value of loved ones’ presence and support became evident from the participants’ accounts. For example, Aila emphasised the meaning of her large family and circle of friends in her life. Similarly, Laura addressed her sister's help and the support she received from their ‘new nest’, including her child and the people who take care of her. Some participants received assistance from home care services or from their siblings in managing the activities of daily living. Public transportation, transportation services, and familiar environments and routes supported them in moving from place to place, but also the courage to ask people around them for help when needed was brought up.

Guidance and counselling

We were also interested in hearing our participants’ views of getting information and services, and particularly their perspectives on the availability of guidance and counselling. The participants had varying experiences of receiving adequate guidance and counselling. This tendency was not related to geographical location in our data. Some considered that they received somewhat enough information, help and advice, while others pointed out the scarcity of available guidance and counselling. The Alzheimer Society has been a source of information for many participants, for instance about how to apply for transportation services.

Typically, the participants talked about one person (a family member, a person providing health care, etc.) who gave them information and help in, for example, finding services or filling application forms. Ossi received help from his family: ‘I didn't know much at the beginning either but the children and wife, indeed, with their help I have got forward.’ Conversely, Arja expressed the feeling of not getting information from anywhere: ‘I only say that I'm a person with bad luck.’

Thus, obtaining guidance and counselling seems to be quite random and dependent on whether or not there happens to be someone who knows the information or could find it out. Even if information was available immediately after the person received the diagnosis, it might not always have been the right time to explore it. There also seems to be a lack of continuity in guidance and counselling, as can be seen from Jaakko's account:

But then afterwards when there wasn't any, I think there was no adaptation or coaching course or anything like that so you could have gone somewhere. There was no discussion of these. I have this impression.

The availability of guidance and counselling may affect a person's financial situation if they, for instance, lack information about social security benefits or practical help in applying for them. Jaakko obtained information about social security benefits from his ex-wife: ‘I didn't know about any benefits you can apply for, and I had a person who roughly knew, so I got help from her.’ Senni, again, got help from her relative and from a nurse to complete the application: ‘because I would have been completely lost. One cross [on the form] without and you probably would not have got the money then.’ If adequate help is not available, the digital gap between individuals and groups can manifest itself in cases where the use of technology decreases after a diagnosis with dementia. Senni described how technology is not only essential for accessing information, but also can be used to manage complex issues, e.g. by taking photographs of important information.

The participants suggested different ways to ensure that people receive all the information they need and are in an equal position with respect to obtaining guidance and counselling. First, some addressed the need to ensure that important information is always on paper. Second, guidance and counselling should be available not only after receiving a diagnosis, but also later and provided by various stakeholders to ensure that the ‘shock phase’ does not hinder people's access to it. Third, the participants highlighted the need to create a care pathway that would be the same for all ranging from medical investigations to the time of living with dementia:

…if it is good for someone, they have luck on their side, but it should be the same for everyone, everyone ought to be equal despite what the diagnosis will be.

Legal tools for later-life planning

Sooner or later, a person with dementia normally loses their capability to make independent decisions. In that situation, a guardian – in Finland a public guardian or a loved one – may be appointed. Alternatively, a person may anticipate the loss of capacity by conducting legal planning with continuing powers of attorney or an advanced health-care directive. A continuing power of attorney is a deed where a person appoints a proxy decision-maker to make decisions if they later lose their capacity to take care of their own affairs.

The participants’ descriptions show that handing over the control of decisions concerning one's own life may not be an easy thing to do, and trust in the person appointed as a guardian is very important. Some of the participants preferred that a loved one take care of their affairs, whereas others considered it safe for this to be done by a public guardian. Maintaining communication and asking the person's own opinion, i.e. letting them participate in decision-making, were important to build this trust. To Jaana, having a public guardian appointed first caused doubts and fear, but meeting the person face-to-face dispelled her worries:

The first time when Laina [a person providing home care] said that I needed a guardian, I was angry. I said, my money will not be taken anywhere – go away. I got angry at her … Because I have always taken care of myself, I thought that they would take my money or something … I wasn't even able to sleep very well because I was afraid of it. However, when I got to see these people [at the guardianship office], I saw that they are not cheating or anything. And they have done a good job.

The participants wanted to avoid giving the power to the wrong person. Mistrust could be felt towards a total stranger or, alternatively, a ‘greedy’ relative: ‘He is so greedy for money, waiting for me to die. Really.’ Sometimes the problem was that there was no one close to whom the continuing powers of attorney could be appointed. In other instances, the legal tools for later-life planning were not yet seen as pressing; people trusted their relational safety net to take care of their issues if they later become unable to manage their affairs. Some addressed, however, the necessity of drawing up a continuing power of attorney or express one's own will with an advanced heath-care directive early enough, in light of the progressive nature of dementia:

Senni: Then these are the kind of things that these should be early enough, even though, even if you haven't got ill, these should be done.

Arja: That's true.

Senni: Earlier rather than late because then it's too late; if it goes over that certain threshold, then you don't have the chance to influence it anymore. Now, when the mind still works that much.

Arja: It's worth doing it beforehand.

The discussion above illustrates the importance to some of the participants of anticipating their future. It was a matter of their autonomy being respected even when they have lost their capacity to express their will and preferences.

Theme 3: Fighting the stigma associated with (working-age) dementia

The changes that follow stopping work can be not only concrete but also symbolic. The feeling of losing one's value that so often tends to be interwoven with working was described as ‘depressing’. Among working-age people, concealing one's health condition often stemmed from the stigma associated with disability: ‘Because I was ashamed. I was so terribly ashamed. Because I had always been working.’

The social network of an individual living with dementia also may shrink when other people start avoiding them. Aila said that even though she was not ashamed of dementia, being open about it had a price when many people vanished from her life. In the discussion below, Laura states that a person living with dementia is thrown in the garbage can. When asked what she meant, she clarified that the person disappears.

Aila: I miss people.

Laura: It is. A person with a memory disease today, they are thrown in the trash can right away.

Aila: That's true.

Laura: Really.

Consequently, all three groups highlighted the need to question and fight the stigma: ‘The most important thing is to treat people as equal, not to look awry, that they don't realise anything.’ Furthermore, when asked what kind of advice they would give to people who face a similar situation, several participants voiced the importance of ‘continuing life’ despite the changes, ‘not staying in the corner’ but seeking new and meaningful activities. Some described the meaning of thinking of the good sides of not working anymore, living for today and acknowledging one's life as it is as valuable: ‘I did think that this kind of life is quite a good life.’ Finding positive perspectives was, however, usually described as a process in which ‘time helps’.

Table 2 summarises the results from the perspective of different resources and impediments for influencing one's life when living with working-age dementia.

Discussion

This inter-disciplinary study aimed at exploring how working-age people living with dementia seek to influence their lives, and what makes it easier or more difficult for them in their everyday life. The results (see Table 2) illuminate various resources that enable a person to (a) handle their difficulties at work and related consequences with dignity, (b) manage everyday tasks and live a fulfilling life, as well as (c) fight the stigma associated with (working-age) dementia. Challenges related to these aspects reported by the participants revealed gaps and obstacles to the full realisation of rights of people who live with early onset dementia.

The difficulties the participants experienced at work manifested in challenges (see also e.g. Chaplin and Davidson, Reference Chaplin and Davidson2016) such as memory problems, difficulties in managing new work tasks and stress caused, such as by fast-paced work. As the results show, delays in recognising the need for medical investigations may result, for example, from wrongly attributing difficulties to incompetence, laziness or alcoholism. Thus, consistent with the results of earlier research, some people face distressing experiences of unfair treatment or are not given a voice when making decisions about when it is time to stop working (Chaplin and Davidson, Reference Chaplin and Davidson2016; Ritchie et al., Reference Ritchie, Tolson and Danson2018). Emotional and practical support at the workplace and opportunities to influence the decisions concerning one's future with work can make the situation easier for the person. However, it seems that opportunities to make reasonable adjustments are not always sufficiently explored, which is in line with the results of previous studies (Egdell et al., Reference Egdell, Cook, Stavert, Ritchie, Tolson and Danson2019; Thomson et al., Reference Thomson, Stanyon, Dening, Heron and Griffiths2019).

Often, the mismatch between a person's health condition and psychosocial working conditions means that they find it impossible to continue working (see also e.g. Ritchie et al., Reference Ritchie, Tolson and Danson2018). This result highlights the importance of both listening to and respecting the person's own views when making decisions about continuing work and timely retirement, and recognising how today's working life is characterised (e.g. by high time pressure and continuous need to learn new skills and knowledge). All too often, the structure of work and its related systems are inflexible and exclusionary for people living with a disability. Therefore, more research is needed regarding practices that enable an employee who develops dementia and wishes to continue working to identify, implement and refine the accommodations required to meet their individual needs.

Timely access to different kinds of social and material resources is critically important to being able to influence one's life when living with early onset dementia, both while working and after leaving employment. The loss of daily routines challenges them to find new and meaningful activities after they retire from work. For some, this means building new social connections and engaging in activities with people who ‘understand’ because they are in a similar situation. Opportunities to ponder and gain helpful perspectives about one's situation through discussions with peers should therefore be available. As found in other studies, a person's social network commonly shrinks when they lose their social contacts in the workplace (see also Ritchie et al., Reference Ritchie, Tolson and Danson2018). Losing a meaningful part of one's identity (see also Harris, Reference Harris2004) because of disability may, in turn, provoke feelings of shame and worthlessness. This view was reinforced in this study as former friends and colleagues ‘vanished’ from their lives, particularly when participants shared their dementia diagnosis. This could reflect the double stigma of dementia and ageism (Evans, Reference Evans, Ayalon and Tesch-Römer2018), with people living with early onset dementia being viewed by contemporaries as older adults. As Patterson et al. (Reference Patterson, Clarke, Wolverson and Moniz-Cook2018) note, other people can facilitate either their feelings of being ‘outcast and relegated’ or ‘included or valued’. Thus, we all have the responsibility to question and replace responses to (early onset) dementia that are harmful to people living with it.

Receiving adequate and timely guidance and counselling is a legal right; nevertheless, the participants in this study reported gaps in provision that mainly related to the lack of continuity in guidance and counselling and inequalities in access to it (see also Mayrhofer et al., in press). This suggests the need to build the same care pathway for everyone to ensure their ongoing and equal access to information and services. High-quality guidance and counselling based on multi-disciplinary expertise creates conditions for people to participate in decision-making concerning themselves by providing timely information and support (Heimonen and Mäki-Petäjä-Leinonen, Reference Heimonen and Mäki-Petäjä-Leinonen2018; Nikumaa and Mäki-Petäjä-Leinonen, Reference Nikumaa and Mäki-Petäjä-Leinonen2019).

Some participants reported that anticipating their future was very important to them. Handing over the control of decisions concerning one's own life can be particularly challenging if a person is used to independent decision-making. Thus, it is important that in cases when a substitute decision-maker becomes involved, such as a guardian or a trustee, this person listens to the individual with early onset dementia and empowers them to participate in the decision-making process as much as possible. Having someone who communicates openly and whom the person can trust is of utmost importance. This was also important for other participants who relied strongly on their relational safety nets in decision-making. For them written documents were not that important or urgent, as they trusted their families’ support and help with decision-making.

The present study supports conceptualising autonomy of people living with dementia as a relational phenomenon (see also e.g. Harding, Reference Harding, Foster, Herring and Doron2014) that is shaped in the interaction of interpersonal, material and discursive aspects. The ways in which external conditions appeared in our participants’ accounts were twofold. Firstly, their actual possibilities for autonomy (i.e. lived experiences of influencing one's life) were often affected by external resources and impediments; psychosocial working conditions, support, information and services available to them, as well as societal values and expectations that played influential and important roles in positively or negatively impacting outcomes. Secondly, the participants reflected on their social relations and the characteristics of material and socio-cultural environment to explain what is good for them (and others) in their particular situation. With this perspective in mind, ensuring meaningful participation by the individual themselves is crucial to supporting both a sense of being full members of society and autonomy of people living with early onset dementia.

The study has several limitations that need to be addressed through future work. While three focus groups can be enough to reveal prevalent themes (Guest et al., Reference Guest, Namey and McKenna2017), the small number of focus groups and participants in each group may have influenced the quality of the data. Group discussions may have also facilitated the expression of shared understandings and given less space for individual participants to communicate their personal aims and preferences. The majority lived alone and all took part in the activities provided by the local associations of the Alzheimer Society, which might have influenced the findings; they might have, for instance, placed greater emphasis on the role of peer support and shared activities, or had better access to them as well as to guidance and counselling than individuals outside these occupations. Furthermore, all participants lived in large cities, which may be one reason for some of the similarities between their experiences.

Despite the limitations of the study, the results contribute to the knowledge base of different social and environmental aspects (Clare et al., Reference Clare, Wu, Jones, Victor, Nelis, Martyr, Quinn, Litherland, Pickett, Hindle, Jones, Knapp, Kopelman, Morris, Rusted, Thom, Lamont, Henderson, Rippon, Hillman and Matthews2019) that contribute to a person's possibilities for influencing their own life when living with early onset dementia; this, in turn, profoundly impacts their ability to live well. From a practical and policy point of view, the results demonstrate a lack of knowledge and understanding about the signs of dementia in the workforce. This lack highlights an urgent and compelling need for dementia awareness and workplace education for managers and employees about signs of cognitive impairment in general and appropriate responses to difficulties at work. Similarly, employers, human resource managers and occupational health-care professionals should be offered education about the legal rights of individuals with early onset dementia and the importance of building good practices to enable them to influence decision-making about their future. Such good practice should include strategies for facilitating timely planning discussions that enable individuals with early onset dementia to participate fully. These kinds of practices would also be beneficial for other people with cognitive impairments. Furthermore, there is a need to integrate services between health care, social care and the third sector (Mayrhofer et al., in press) to provide adequate post-diagnostic support that meets the individual needs of people living with early onset dementia.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the participants who shared their experiences and thoughts with us. Many thanks also to the staff members of the Alzheimer Society of Finland for their help in recruiting participants and providing facilities for the group discussions. We would also like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their feedback which greatly helped to improve the earlier versions of this article.

Author contributions

MI, AM-P-L and SH gathered the data. MI (main responsibility) and AM-P-L analysed the data and drafted the manuscript. All authors reviewed and revised the manuscript.

Financial support

This study is a part of the research project ‘Dementia or Mild Cognitive Impairment: @ Work in Progress’ supported by the Academy of Finland (grant number 318848); Swedish Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare, FORTE (grant number 2017-02303); the Canadian Institute for Health Research (grant number MYB155683) under the framework of the JPI MYBL; and the Ontario Shores Research Chair in Dementia Well-being (AA); as well as the research project ‘Working Life and Memory Impairment – Mental Wellbeing, Legal Security and Occupational Capacity of People with Early Onset Dementia’ supported by the Academy of Finland (grant number 314749).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the University of Eastern Finland Committee on Research Ethics (19/2018, 20/2018).