Abstract

The field of bullying research deals with methodological issues and concerns affecting the comprehension of bullying and how it should be defined. For the purpose of designing relevant and powerful bullying prevention strategies, this article argues that instead of pursuing a universal definition of what constitutes bullying, it may be of greater importance to investigate culturally and contextually bound understandings and definitions of bullying. Inherent to that shift is the transition to a more qualitative research approach in the field and a stronger focus on participants’ subjective views and voices. Challenges in qualitative methods are closely connected to individual barriers of hard-to-reach populations and the lack of a necessary willingness to share on the one hand and the required ability to share subjective viewpoints on the other hand. By reviewing and discussing Q methodology, this paper contributes to bullying researchers’ methodological repertoire of less-intrusive methodologies. Q methodology offers an approach whereby cultural contexts and local definitions of bullying can be put in the front. Furthermore, developmentally appropriate intervention and prevention programs might be created based on exploratory Q research and could later be validated through large-scale investigations. Generally, research results based on Q methodology are expected to be useful for educators and policymakers aiming to create a safe learning environment for all children. With regard to contemporary bullying researchers, Q methodology may open up novel possibilities through its status as an innovative addition to more mainstream approaches.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Bullying, internationally recognized as a problematic and aggressive form of behavior, has negative effects, not only for those directly involved but for anybody and in particular children in the surrounding environment (Modin, 2012). However, one of the major concerns among researchers in the field of bullying is the type of research methods employed in the studies on bullying behavior in schools. The appropriateness of using quantitative or qualitative research methods rests on the assumption of the researcher and the nature of the phenomena under investigation (Hong & Espelage, 2012). There is a need for adults to widen their understanding and maintain a focus on children’s behaviors to be able to provide assistance and support in reducing the amount of stress and anxiety resulting from online and offline victimization (Hellström & Lundberg, 2020). A crucial step for widening this understanding is an increased visibility of children’s own viewpoints. When the voices of children, particularly those of victims and perpetrators, but also those of bystanders are heard in these matters, effective support can be designed based specifically on what children want and need rather than what adults interpret and understand to be supporting the child (O’Brien, 2019). However, bullying victims and their perpetrators are hard-to-reach populations (Shaghaghi et al., 2011; Sydor, 2013) for a range of reasons. To name but a few, researchers perennially face difficulties regarding potential participants’ self-identification, the sensitivity of bullying topics, or the power imbalance between them and their young respondents. Furthermore, limited verbal literacy and/or a lack of cognitive ability of some respondents due to age or disability contribute to common methodological issues in the field. Nevertheless, and despite ethical restrictions around the immediate questioning of younger children or children with disabilities that prohibit researchers to perform the assessments with them directly, it would be ethically indefensible to not study a sensitive topic like bullying among vulnerable groups of children. Hence, the research community is responsible for developing valid and reliable methods to explore bullying among different groups of children, where the children’s own voices are heard and taken into account (Hellström, 2019). Consequently, this paper aims to contribute to bullying researchers’ methodological repertoire with an additional less-intrusive methodology, particularly suitable for research with hard-to-reach populations.

Historically, the field of bullying and cyberbullying has been dominated by quantitative research approaches, most often with the aim to examine prevalence rates. However, recent research has seen an increase in the use of more qualitative and multiple data collection approaches on how children and youth explain actions and reactions in bullying situations (e.g., Acquadro Maran & Begotti, 2021; Eriksen & Lyng, 2018; Patton et al., 2017). This may be translated into a need to more clearly understand the phenomenon in different contexts. As acknowledged by many researchers, bullying is considerably influenced by the context in which it occurs and the field is benefitting from studying the phenomenon in the setting where all the contextual variables are operating (see, e.g., Acquadro Maran & Begotti, 2021; Scheithauer et al., 2016; Torrance, 2000). Cultural differences in attitudes regarding violence as well as perceptions, attitudes, and values regarding bullying are likely to exist and have an impact when bullying is being studied. For this reason, listening to the voices of children and adolescents when investigating the nature of bullying in different cultures is essential (Hellström & Lundberg, 2020; Scheithauer et al., 2016).

In addition to studying outcomes or products, bullying research has also emphasized the importance of studying processes (Acquadro Maran & Begotti, 2021). Here, the use of qualitative methods allows scholars to not only explore perceptions and understandings of bullying and its characteristics, but also interpret bullying in light of a specific social context, presented from a specific internal point of view. In other words, qualitative approaches may offer methods to understand how people make sense of their experiences of the bullying phenomenon. The processes implemented by a qualitative approach allow researchers to build hypotheses and theories in an inductive way (Atieno, 2009). Thus, a qualitative approach can enrich quantitative knowledge of the bullying phenomenon, paying attention to the significance that individuals attribute to situations and their own experiences. It can allow the research and clinical community to better project and implement bullying assessment and prevention programs (Hutson, 2018).

Instead of placing qualitative and quantitative approaches in opposition, they can both be useful and complementary, depending on the purpose of the research (Acquadro Maran & Begotti, 2021). In their review of mixed methods research on bullying and peer victimization in school, Hong and Espelage (2012) underlined that instead of using single methods, mixed methods have the advantage of generating a deeper and more complex understanding of the phenomenon. By combining objective data with information about the personal context within which the phenomenon occurs, mixed methods can generate new insights and new perspectives to the research field (Hong & Espelage, 2012; Kulig et al., 2008; Pellegrini & Long, 2002). However, Hong and Espelage (2012) also argued that mixed methods can lead to divergence and contradictions in findings that may serve as a challenge to researchers. For example, Cowie and Olafsson (2000) examined the impact of a peer support program to reduce bullying using both quantitative and qualitative data collection methods. While a quantitative approach collecting pre-test and post-test data showed no effects in decreasing bullying, interviews with peer supporters, students, and potential users of the intervention revealed the strength of the program and its positive impact, in light of students and peer supporters. Thus, rather than rejecting the program, the divergence in findings leads to a new rationale for modifying the program and addressing its limits.

Understandably, no single data collection approach is complete but deals with methodological issues and concerns affecting the research field and the comprehension of bullying. To provide a robust foundation for the introduction of an additional methodological perspective in bullying research, common data collection methods and methodological issues are outlined below.

Methodological Issues in Bullying Research

Large-scale cohort studies generating statistical findings often use R-statistics, descriptive analyses, averages, and correlations to estimate and compare prevalence rates of bullying, to explore personality traits of bullies and victims, and the main correlates and predictors of the phenomenon. Nevertheless, large-scale surveys have a harder time examining why bullying happens (O’Brian, 2019) and usually do not give voice to study objects’ own unique understanding and experiences (Acquadro Maran & Begotti, 2021; Bosacki et al., 2006; Woodhead & Faulkner, 2008). Other concerns using large-scale surveys include whether a definition is used or the term bullying is operationalized, which components are included in the definition, what cut-off points for determining involvement are being used, the lack of reliability information, and the absence of validity studies (Swearer et al., 2010).

Other issues include the validity in cross-cultural comparisons using large-scale surveys. For example, prevalence rates across Europe are often established using standard questionnaires that have been translated into appropriate languages. Comparing four large-scale surveys, Smith et al. (2016) found that when prevalence rates by country are compared across surveys, there are some obvious discrepancies, which suggest a need to examine systematically how these surveys compare in measuring cross-national differences. Low external validity rates between these studies raise concerns about using these cross-national data sets to make judgments about which countries are higher or lower in victim rates. The varying definitions and words used in bullying research may make it difficult to compare findings from studies conducted in different countries and cultures (Griffin & Gross, 2004). However, some argue that the problem seems to be more about inconsistency in the type of assessments (e.g., self-report, nominations) used to measure bullying rather than the varying definition of bullying (Jia & Mikami, 2018). When using a single-item approach (e.g., “How often have you been bullied?”) it is not possible to investigate the equivalency of the constructs between countries, which is a crucial precondition for any statistically valid comparison between them (Scheithauer et al., 2016). Smith et al. (2016) conclude that revising definitions and how bullying is translated and expressed in different languages and contexts would help examine comparability between countries.

Interviews, focus groups and the use of vignettes (usually with younger children) can all be regarded as suitable when examining youths’ perceptions of the bullying phenomenon (Creswell, 2013; Hellström et al., 2015; Hutson, 2018). They all allow an exploration of the bullying phenomenon within a social context taking into consideration the voices of children and might solve some of the methodological concerns linked to large-scale surveys. However, these data collection methods are also challenged by individual barriers of hard-to-reach populations (Ellard-Gray et al., 2015) and may include the lack of a necessary willingness to share on the one hand and the required ability to share subjective viewpoints on the other hand.

Willingness to Share

In contrast to large-scale surveys requiring large samples of respondents with reasonable literacy skills, interviews, which may rely even heavier on students’ verbal skills, are less plentiful in bullying research. This might at least partially be based on a noteworthy expectation of respondents to be willing to share something. It must be remembered that asking students to express their own or others’ experiences of emotionally charged situations, for example concerning bullying, is particularly challenging (Khanolainen & Semenova, 2020) and can be perceived as intrusive by respondents who have not had the opportunity to build a rapport with the researchers. This constitutes a reason why research in this important area is difficult and complex to design and perform. Ethnographic studies may be considered less intrusive, as observations offer a data collection technique where respondents are not asked to share any verbal information or personal experiences. However, ethnographical studies are often challenging due to the amount of time, resources, and competence that are required by the researchers involved (Queirós et al., 2017). In addition, ethnographical studies are often used for other purposes than asking participants to share their views on certain topics.

Vulnerable populations often try to avoid participating in research about a sensitive topic that is related to their vulnerable status, as recalling and retelling painful experiences might be distressing. The stigma surrounding bullying may affect children’s willingness to share their personal experiences in direct approaches using the word bullying (Greif & Furlong, 2006). For this reason, a single-item approach, in which no definition of bullying is provided, allows researchers to ask follow-up questions about perceptions and contexts and enables participants to enrich the discussion by adjusting their answers based on the suggestions and opinions of others (Jacobs et al., 2015). Generally, data collection methods with depersonalization and distancing effects have proven effective in research studying sensitive issues such as abuse, trauma, stigma and so on (e.g., Cromer & Freyd, 2009; Hughes & Huby, 2002). An interesting point raised by Jacobs and colleagues (2015) is that a direct approach that asks adolescents if they have ever experienced cyberbullying may lead to a poorer discussion and an underestimation of the phenomenon. This is because perceptions and contexts often differ between persons and because adolescents do not perceive all behaviors as cyberbullying. The same can be true for bullying taking place offline (Hellström et al., 2015).

When planning research with children, it is important to consider the immediate research context as it might affect what children will talk about (Barker & Weller, 2003; Hill, 2006; Punch, 2002). In addition to more material aspects, such as the room or medium for a dialog, the potential power imbalance created in an interview situation between an adult researcher and the child under study adds to a potentially limited willingness to share. Sitting in front of an adult interviewer may create situations where children may find it difficult to express their feelings and responses may be given based on perceived expectations (Punch, 2002). This effect is expected to be even stronger when studying a sensitive topic like bullying. Therefore, respondents may provide more honest responses when they are unaware that the construct of bullying is being assessed (Swearer et al., 2010). Moreover, in research about sensitive topics, building a strong connection with participants (Lyon & Carabelli, 2016), characterized by mutual trust, is vital and might overcome the initial hesitation to participate and share personal accounts. Graphic vignettes have successfully been used as such unique communication bridges to collect detailed accounts of bullying experiences (Khanolainen & Semenova, 2020). However, some reluctance to engage has been reported even in art-based methods, usually known to be effective in research with verbally limited participants (Bagnoli, 2009; Vacchelli, 2018) or otherwise hard-to-reach populations (Goopy & Kassan, 2019). Most commonly, participants might not see themselves as creative or artistic enough (Scherer, 2016). In sum, the overarching challenging aspect of art-based methods related to a limited willingness to share personal information is an often-required production of some kind.

Ability to Share

Interviews as a data collection method demand adequate verbal literacy skills for participants to take part and to make their voices heard. This may be challenging especially for younger children or children with different types of disabilities. There is a wide research gap in exploring the voices of younger children (de Leeuw et al., 2020) and children with disabilities (Hellström, 2019) in bullying research. Students’ conceptualization of bullying behavior changes with age, as there are suggestions that younger students tend to focus more on physical forms of bullying (such as fighting), while older students include a wider variety of behaviors in their view of bullying, such as verbal aggression and social exclusion (Hellström & Lundberg, 2020; Monks & Smith, 2006; Smith et al., 2002; Hellström et al., 2015). This suggests that cognitive development may allow older students to conceptualize bullying along a number of dimensions (Monks & Smith, 2006). Furthermore, the exclusion of the voices of children with disabilities in bullying research is debated. It is discussed that the symptoms and characteristics of disabilities such as Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) or Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), i.e., difficulties understanding the thoughts, emotions, reactions, and behaviors of others, which makes them the ideal target for bullying may also make it hard for them to perceive, verbalize and report bullying and victimization in a reliable and valid manner (Slaughter et al., 2002). It may also be difficult for children with ASD to differentiate between playful teasing among friends and hurtful teasing. While many argue that children with ASD are unreliable respondents of victimization, under-reporting using parental and teacher reports has been shown in research on bullying (Waters et al., 2003; Bradshaw et al., 2007) and child maltreatment (Compier-de Block et al., 2017).

This Paper’s Contribution

The present paper contributes to this special issue about qualitative school bullying and cyberbullying research by reviewing and discussing Q methodology as an innovative addition to more mainstream approaches in the field. Despite the fact that Q methodology had been proclaimed as “especially valuable […] in educational psychology” (Stephenson, 1935, p. 297) nearly 90 years ago, the approach has only relatively recently been described as an up-and-coming methodological choice of educational researchers interested in participants’ subjective views (Lundberg et al., 2020). Even though, Q enables researchers to investigate and uncover first-person accounts, characterized by a high level of qualitative detail in its narrative description, only few educational studies have applied Q methodology to investigate the subject of bullying (see Camodeca & Coppola, 2016; Ey & Spears, 2020; Hellström & Lundberg, 2020; Wester & Trepal, 2004). Within the wider field of bullying, Q methodology has also been used to investigate workplace bullying in hospitals (Benmore et al., 2018) and nursing units (Choi & Lee, 2019). By responding to common methodological issues outlined earlier, the potential Q methodology might have for bullying research is exemplified. A particular focus is thereby put on capturing respondents’ subjective viewpoints through its less-intrusive data collection technique. The present paper closes by discussing implications for practice and suggesting future directions for Q methodological bullying and cyberbullying research, in particular with hard-to-reach populations.

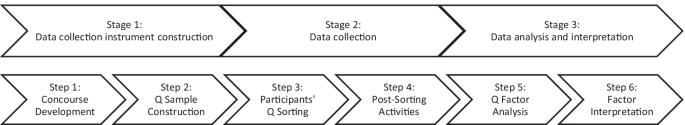

An Introduction to Q Methodology

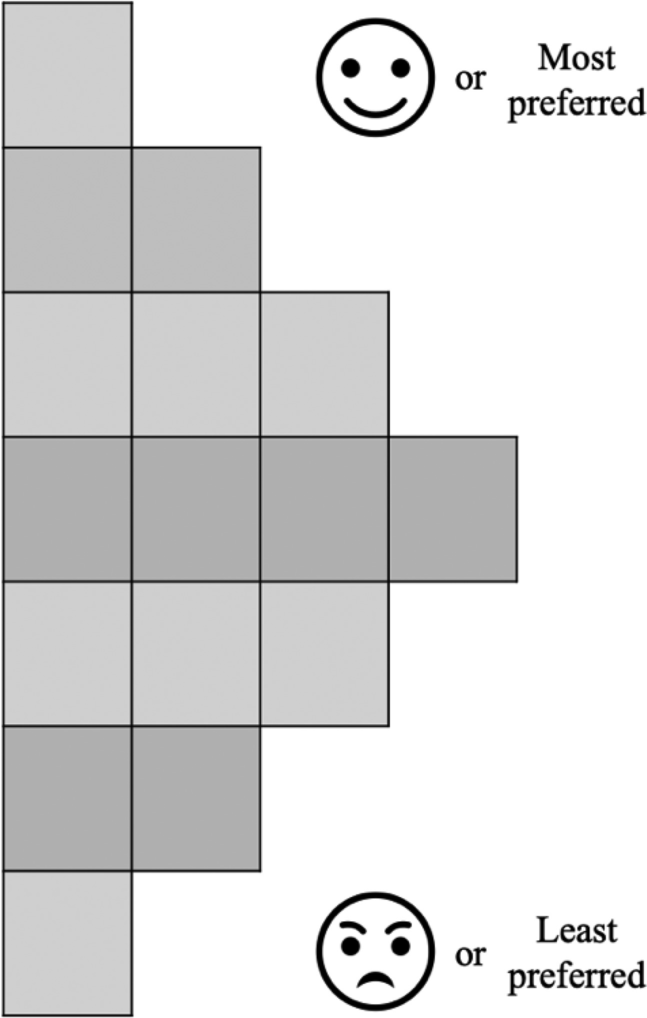

Q as a methodology represents a larger conceptual and philosophical framework, which is by no means novel. However, the methodology has largely been marginalized since its invention in the 1930s by William Stephenson (Brown, 2006). As a research technique, it broadly consists of three stages that each can be split into a set of steps (see Fig. 1); (1) carefully constructing a data collection instrument, (2) collecting data, and (3) analyzing and interpreting data. The central, and therefore also best-known feature of Q methodology is Q sorting to collect data in the form of individual Q sorts. Participants thereby rank order a sample of self-referent stimuli along a continuum and in accordance with a central condition of instruction; for example, children might be asked to what extent particular scenarios describe bullying situations (Hellström & Lundberg, 2020) or they might be instructed to sort illustrated ways to resolve social exclusion according to the single face-valid dimension of “least preferred to most preferred” (de Leeuw et al., 2019). As soon as all items are placed on a most often bell-shaped distribution grid (see Fig. 2), participants might be asked to elaborate on their item placement to add a further layer of qualitative data. Such so-called post-sorting activities might include written annotations of items placed at the ends of the continuum or form the structure for interviews (Shemmings & Ellingsen, 2012).

Three stages and six steps of a Q methodological research process (adapted from Lundberg et al., 2020)

For participants to provide their subjective viewpoint toward a specific topic in the form of a Q sort, researchers need to construct the data collection instrument, called Q sample. Such a set of stimulus items is a representative sample from all possible items concerning the topic, which in the technical language in Q methodology is called concourse (Brown, 1980). The development of such a concourse about the topic at hand might stem from a wide range of sources, including academic literature, policy documents, informal discussions, or media (Watts & Stenner, 2012). Moreover, in a participatory research fashion, participants’ statements can be used verbatim to populate the concourse. This way, children’s own words and voices are part of the data collection instrument. A sophisticated structuring process then guides the researchers in selecting a Q sample from all initial statements in the concourse (Brown et al., 2019). In Hellström & Lundberg (2020), a literature review on findings and definitions of bullying, stemming from qualitative and quantitative research, provided the initial concourse. A matrix consisting of different modes, types, and contexts of bullying supported the construction of the final Q sample.

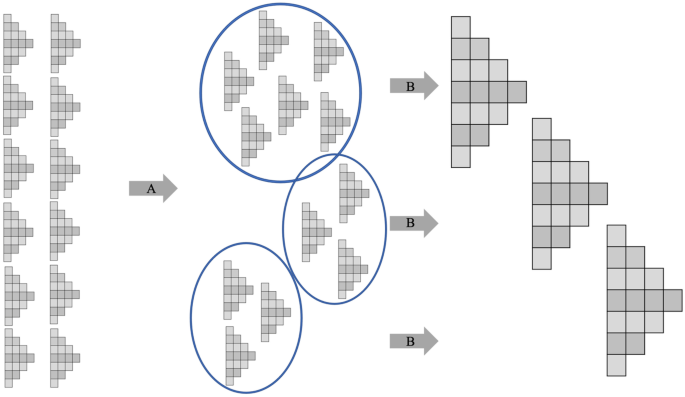

As a student and assistant of Charles Spearman, Q’s inventor Stephenson was well-informed about R-methodological factor analysis based on correlating traits. The British physicist-psychologist however inverted the procedure and thereby suggested correlating persons to study human behavior (Stephenson, 1935, 1953). A detailed description of the statistical procedure of Q factor analysis is outside the scope of this article, especially as the focus of this special issue is put on qualitative research methods. In addition, with its focus on producing quantifiable data from highly subjective viewpoints (Duncan & Owens, 2011), it is safe to say that Q methodology is more often treated as a qualitative methodology with quantitative features than the other way around. Nevertheless, it is important to note that through factor analysis, individual viewpoints are clustered into so-called factors, representing shared viewpoints if they sufficiently correlate (see Fig. 3). In that sense, no outside criterion is applied to respondents’ subjective views and groups of similar sorts (factors/viewpoints) are not logically constructed by researchers. Instead, they inductively emerge through quantitative analysis, which helps “in learning how the subject, not the observer, understands and reacts to items” (Brown, 1980, p. 191). This procedure allowed Hellström & Lundberg (2020) to describe two age-related definitions of bullying. Older students in particular perceived offline bullying as more severe than online bullying and their younger peers were mostly concerned about bullying situations taking place in a private setting.

Despite its quantitative analysis, participant selection in Q methodology is largely in line with purposive sampling with small numbers. It, therefore, represents a major difference to R methodological research, where larger opportunity samples are desired. In Q methodology, participants are selected strategically in line with those who might likely “express a particularly interesting or pivotal point of view” (Watts & Stenner, 2012, p. 71). Investigating a large number of similar respondents might therefore simply lead to more participants correlating with the same shared viewpoint and not necessarily add new viewpoints. In recent educational Q research, the average number of participants is 37 (Lundberg et al., 2020). Many studies have however been successfully conducted with considerably fewer, as for example illustrated by Benmore et al. (2018), who described three distinctive groups within their sample of 12 participants.

An Example

To illustrate Q methodology in bullying research, our small scale and exploratory study published in Educational Research (Hellström & Lundberg, 2020) serves as a practical example. The purpose of that study was to investigate definitions of bullying from young people’s perspectives and was guided by the following research question: What are students’ subjective viewpoints on bullying behavior?. In Table 1, we describe the methodological steps introduced in Fig. 1.

Q Methodology’s Response to the Methodological Issues Outlined Above

Above, methodological issues have been structured according to participants’ willingness and ability to share their subjective viewpoints and lived experiences. In order to respond to those, the present section focuses on Q methodology’s built-in features. A particularly important component is Q sorting as the central data collection technique that facilitates participants’ communicability of their subjectivity.

Willingness to Share

Engaging participants in a card sorting activity encourages students to express their viewpoints and thereby making their voices heard in a less-intrusive way, despite being cognitively engaging. Because they are asked to rank-order a predetermined sample of items, ideally in accordance with a carefully selected condition of instruction, they do not need to report or disclose their own personal experiences and are not obliged to actively create anything, as criticized in arts-based research. In that sense, Q methodology can be seen as a method to collect sensitive data in a more depersonalized way. This provides the basis to find a vital “balance between protecting the child and at the same time allowing access to important information” (Thorsen & Størksen, 2010, p. 9), which is of particular importance for research about emotionally charged situations or sensitive topics as it is often the case with bullying (Ellingsen et al., 2014). Sharing their view through a fixed collection of items certainly makes participation in research for young children or otherwise hard-to-reach respondents less intimidating and results can be expected to be more truthful.

In comparison to researchers applying ethnographical approaches, who immerse themselves into the studied context to understand and document patterns of social behavior and interaction in a less intrusive way, Q methodologists are not expected to observe their participants. Even though the purpose of these approaches is different, being part of the culture under investigation or at least involving community partners in Q methodological research can still be useful for at least two reasons. As mentioned in Table 1 featuring the study by Hellström & Lundberg (2020), the pupils’ physical education and health teacher guided an exploratory and informal discussion and thereby provided valuable insights into the participants’ lifeworld that informed the Q sample. In addition to better tailoring the sample to the participants and making them feel seen and heard, the community partner could help build a positive rapport between participants and researchers, which otherwise requires much work. During the actual data collection exercise, participants were already familiar with the topic, well-informed about the research project, and perceived the sorting activity as an integral part of their lesson.

The play-like character of Q sorting has as well been reported as a positive influence on respondents’ motivation to participate (de Leeuw et al., 2019) and Wright (2013) mentions the engaging atmosphere created between the sorter and the researcher. The combination of these features allows assuming that obtaining participants’ viewpoint through Q methodology is less threatening than for example sitting in front of an interviewer and providing on-spot oral responses about a sensitive topic.

Ability to Share

Q sorting as a data collection instrument represents a major advantage for Q methodological research with participants that do not (yet) possess sufficient verbal literacy and/or cognitive ability to process receptive or expressive language. To illustrate, two features are outlined here: first the flexibility of the Q sample, say the set of stimuli and second the fact that primary data collection in Q methodology is based on a silent activity.

Written statements are undoubtedly the most common type of items used in Q methodology and the number of such in a Q sample greatly varies. In recent research reporting from compulsory education settings, the average Q sample consists of about 40 items (Lundberg et al., 2020). In addition to applying a smaller set of items, their complexity can easily be adapted in line with participants’ receptive literacy skills and their developmental stage to facilitate understanding. Statements can for example be shortened or they can start identically to make the activity less taxing (Watts & Stenner, 2012). A different approach to cater to limited verbal literacy is the use of images instead of written statements. Constructing a visual Q sample might be more challenging for the researcher, in particular, if images are carefully selected and culturally tailored, meaning that they are clear, appealing and without too many details (Thorsen & Størksen, 2010). It might nevertheless be worth it, as such items provide a powerful tool to elicit viewpoints from otherwise marginalized or hard-to-reach research participants. Combes and colleagues (2004) for example, created a 37-item-Q sample with intellectually disabled participants’ own pictures to evaluate the planning of activities and de Leeuw et al. (2019) have used 15 images of hypothetical scenarios of social exclusion in a study with primary school pupils. Furthermore, as illustrated by Allgood and Svennungsen (2008) who photographed their participant’s own sculptures, Q samples consisting of objects (e.g., toys) or symbols (emojis) might be other options to investigate issues about bullying and cyberbullying without using text.

In addition to adaptations to the data collection instrument, the sorting process is usually carefully introduced and illustrated. Researchers might want to go through the entire Q sample to ensure the participants are able to discriminate each item (Combes et al., 2004). Even with adult participants without any cognitive impairments, it is suggested to pre-sort items into three provisional categories (Watts & Stenner, 2012). Two categories represent the respective ends of the continuum in the distribution grid and might be labeled and. Any items the sorter feels insecure or neutral about, are moved to the third category, which receives a question mark (?) for the sake of this exercise. During the actual rank-ordering process, the participants start to allocate items to one of the ends of the continuum (the top of the distribution grid in Fig. 2) with cards from the ☺ category and work themselves toward the center of the distribution grid. The process continues with items in the ☹ category, which are placed from the opposite end of the continuum toward the center. Any free spots are then filled with the remaining items in the (?) category. The graphic display of their viewpoint has been experienced as enabling for self-reflection (Combes et al., 2004) and might be utilized for a further discussion about the topic, for example as part of teacher workshops (Ey & Spears, 2020).

Meeting children at an appropriate cognitive level through adaptations of the data collection instrument and procedure, is not only a promising and important ethical decision in order to show young participants the respect they deserve (Thorsen & Størsken, 2010), but makes the sorting procedure a pleasant experience for the participants (John et al., 2014). Unsurprisingly, Q methodology has been described as a respectful, person-centered, and therefore child-friendly approach (Hughes, 2016).

Limitations

Despite its potential for bullying research, Q methodology has its limitations. The approach is still relatively unknown in the field of bullying research and academic editors’ and reviewers’ limited familiarity with it can make publishing Q methodological research challenging. Notwithstanding the limitation of not being based on a worked example, the contribution of the present paper hopefully fulfills some of the needed spadework toward greater acceptability within and beyond a field, which has only seen a limited number of Q methodological research studies. Because the careful construction of a well-balanced Q sample is time-consuming and prevents spontaneous research activities, a core set of items could be created to shorten the research process and support the investigation of what bullying means to particular groups of people. Such a Q sample would then have to be culturally tailored to fit local characteristics. Finally, the present paper is limited in our non-comprehensive selection of data collection methods as points of comparison when arguing for a more intensive focus on Q methodology for bullying research.

Future Research Directions

The results of Q methodological studies based on culturally tailored core Q samples would allow the emergence of local definitions connected to the needs of the immediate society or school context. As illustrated by Hellström & Lundberg (2020), even within the same school context, and with the same data collection instrument (Q sample), Q methodology yielded different, age-related definitions of bullying. Or in Wester and Trepal (2004), Q methodological analysis revealed more perceptions and opinions about bullying than researchers usually mention. Hence, Q methodology offers a robust and strategic approach that can foreground cultural contexts and local definitions of bullying. If desired, exploratory small-scale Q research might later be validated through large-scale investigations. A further direction for future research in the field of bullying research is connected to the great potential of visual Q samples to further minimize research participation restrictions for respondents with limited verbal or cognitive abilities.

Implications for Practice

When designing future bullying prevention strategies, Q methodology presents a range of benefits to take into consideration. The approach offers a robust way to collect viewpoints about bullying without asking participants to report their own experiences. The highly flexible sorting activity further represents a method to investigate bullying among groups that are underrepresented in bullying research, such as preschool children (Camodeca & Coppola, 2016). This is of great importance, as tackling bullying at an early age can prevent its escalation (Alsaker & Valkanover, 2001; Storey & Slaby, 2013). Making the voices of the hard-to-reach heard in an unrestricted way and doing research with them instead of about them (de Leeuw et al., 2019; Goopy & Kassan, 2019) is expected to enable them to be part of discussions about their own well-being. By incorporating social media platforms, computer games, or other contextually important activities when designing a Q sample, the sorting of statements in Hellström & Lundberg, (2020) turned into a highly relevant activity, clearly connected to the reality of the students. As a consequence, resulting policy creation processes based on such exploratory studies should lead to more effective interventions and bullying prevention programs confirming the conclusion by Ey and Spears (2020) that Q methodology served as a great model to develop and implement context-specific programs. Due to the enhanced accountability and involvement of children’s own voices, we foresee a considerable increase in implementation and success rates of such programs. Moreover, Q methodology has been suggested as an effective technique to evaluate expensive anti-bullying interventions (Benmore et al., 2018). Generally, research results based on exploratory Q methodology that quantitatively condensates rich data and makes commonalities and diversities among participants emerge through inverted factor analysis are expected to be useful for educators and policymakers aiming to create a safe learning environment for all children. At the same time, Q methodology does not only provide an excellent ground for participatory research, but is also highly cost-efficient due to its status as a small-sample approach. This might be particularly attractive, when neither time nor resources for other less-intrusive methodological approaches, such as for example ethnography, are available. Due to its highly engaging aspect and great potential for critical personal reflection, Q sorting might be applied in classes regardless of representing a part of a research study or simply as a learning tool (Duncan & Owens, 2011). Emerging discussions are expected to facilitate and mediate crucial dialogs and lead toward collective problem-solving among children.

Conclusion

The use of many different terminologies and different cultural understandings, including meaning, comprehension, and operationalization, indicates that bullying is a concept that is difficult to define and subject to cultural influences. For the purpose of designing relevant and powerful bullying prevention strategies, this paper argues that instead of pursuing a universal definition of what constitutes bullying, it may be of greater importance to investigate culturally and contextually bound understandings and definitions of bullying. Although the quest for cultural and contextual bound definitions is not new in bullying research, this paper offers an additional method, Q methodology, to capture participants’ subjective views and voices. Since particularly the marginalized and vulnerable participants, for example, bullying victims, are usually hard to reach, bullying researchers might benefit from a methodological repertoire enriched with a robust approach that is consistent with changes in methodological and epistemological thinking in the field. In this paper, we have argued that built-in features of Q methodology respond to perennial challenges in bullying research connected to a lack of willingness and limited ability to share among participants as well as studying bullying as a culturally sensitive topic. In summary, we showcased how Q methodology allows a thorough and less-intrusive investigation of what children perceive to be bullying and believe that Q methodology may open up novel possibilities for contemporary bullying researchers through its status as an innovative addition to more mainstream approaches.

Availability of Data and Material

Not applicable.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Change history

18 July 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42380-022-00135-9

References

Acquadro Maran, D., & Begotti, T. (2021). Measurement ideas relevant to qualitative studies. In P. K. Smith & J. O’Higgins Norman (Editors). Handbook of bullying (no pages assigned yet). John Wiley & Sons Limited.

Allgood, E., & Svennungsen, H. O. (2008). Toward an articulation of trauma using the creative arts and Q-methodology: A single-case study. Journal of Human Subjectivity, 6(1), 5–24.

Alsaker, F. D., & Valkanover, S. (2001). Early diagnosis and prevention of victimization in kindergarten. In J. Juvonen & S. Graham (Eds.), Peer harassment in school (pp. 175–195). Guilford Press.

Atieno, O. P. (2009). An analysis of the strengths and limitation of qualitative and quantitative research paradigms. Problems of Education in the 21st Century, 13(1), 13–38.

Bagnoli, A. (2009). Beyond the standard interview: The use of graphic elicitation and arts-based methods. Qualitative Research, 9(5), 547–570. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794109343625

Barker, J., & Weller, S. (2003). “Is it fun?” Developing children centred research methods. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 23(1/2), 33–58. https://doi.org/10.1108/01443330310790435

Benmore, G., Henderson, S., Mountfield, J., & Wink, B. (2018). The Stopit! programme to reduce bullying and undermining behaviour in hospitals: Contexts, mechanisms and outcomes. Journal of Health Organization and Management, 32(3), 428–443. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHOM-02-2018-0047

Bosacki, S. L., Marini, Z. A., & Dane, A. V. (2006). Voices from the classroom: Pictorial and narrative representations of children’s bullying experiences. Journal of Moral Education, 35, 231–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057240600681769

Bradshaw, C. P., Sawyer, A. L., & O’Brennan, L. M. (2007). Bullying and peer victimization at school: Perceptual differences between students and school staff. School Psychology Review, 36, 361–382. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2007.12087929

Brown, S. (1980). Political subjectivity: Applications of Q methodology in political science. Yale University Press.

Brown, S. (2006). A match made in heaven: A marginalized methodology for studying the marginalized. Quality and Quantity, 40(3), 361–382. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-005-8828-2

Brown, S., Baltrinic, E., & Jencius, M. (2019) From concourse to Q sample to testing theory. Operant Subjectivity, 41, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.15133/j.os.2019.002

Camodeca, M., & Coppola, G. (2016). Bullying, empathic concern, and internalization of rules among preschool children: The role of emotion understanding. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 40, 459–465.

Choi, J. K., & Lee, B. S. (2019). Response patterns of nursing unit managers regarding workplace bullying: A Q methodology approach. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing, 49, 562–574.

Combes, H., Hardy, G., & Buchan, L. (2004). Using Q-methodology to involve people with intellectual disability in evaluating person-centred planning. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 17, 149–159. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3148.2004.00191.x

Compier-de Block, L. H., Alink, L. R., Linting, M., van den Berg, L. J., Elzinga, B. M., Voorthuis, A., Tollenaar, M. S., & Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J. (2017). Parent-child agreement on parent-to-child maltreatment. Journal of Family Violence, 32, 207–217. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-016-9902-3

Cowie, H., & Olafsson, R. (2000). The role of peer support in helping the victims of bullying in a school with high levels of aggression. School Psychology International, 21, 79–95.

Creswell, J. (2013). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (3rd ed.). Sage.

Cromer, L. D., & Freyd, J. J. (2009). Hear no evil, see no evil? Associations of gender, trauma history, and values with believing trauma vignettes. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 9(1), 85–96. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-2415.2009.01185.x

De Leeuw, R. R., de Boer, A. A., Beckmann, E. J., van Exel, J., & Minnaert, A. E. M. G. (2019). Young children’s perspectives on resolving social exclusion within inclusive classrooms. International Journal of Educational Research, 98, 324–335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2019.09.009

De Leeuw, R. R., Little, C., & Rix, J. (2020). Something needs to be said – Some thoughts on the possibilities and limitations of ‘voice.’ International Journal of Educational Research, 104, 101694. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2020.101694

Duncan, N., & Owens, L. (2011). Bullying, social power and heteronormativity: Girls’ constructions of popularity. Children & Society, 25, 306–316. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1099-0860.2011.00378.x

Ellard-Gray, A., Jeffrey, N. K., Choubak, M., Crann, S. E. (2015). Finding the hidden participant: Solutions for recruiting hidden, hard-to-reach, and vulnerable populations. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406915621420

Ellingsen, I. T., Thorsen, A. A., Størksen, I. (2014). Revealing children’s experiences and emotions through. Q Methodology Child Development Research, 1–9.https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/910529

Eriksen, M. I., & Lyng, S. T. (2018). Relational aggression among boys: Blind spots and hidden dramas. Gender and Education, 30(3), 396–409. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2016.1214691

Ey, L., & Spears, B. (2020). Engaging early childhood teachers in participatory co-design workshops to educate young children about bullying. Pastoral Care in Education, 38, 230–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/02643944.2020.1788129

Greif, J. L., & Furlong, M. J. (2006). The assessment of school bullying. Journal of School Violence, 5, 33–50. https://doi.org/10.1300/J202v05n03_04

Griffin, R. S., & Gross, A. M. (2004). Childhood bullying: Current empirical findings and future directions for research. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 9, 379–400. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1359-1789(03)00033-8

Goopy, S., & Kassan, A. (2019). Arts-based engagement ethnography: An approach for making research engaging and knowledge transferable when working with harder-to-reach communities. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 18, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406918820424

Hellström, L. (2019). A systematic review of polyvictimization among children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity or Autism Spectrum Disorder. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(13), 2280. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16132280

Hellström, L. & Lundberg, A. (2020). Understanding bullying from young people’s perspectives: An exploratory study. Educational Research, 62(4), 414-433. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131881.2020.1821388

Hellström, L., Persson, L. & Hagquist, C. (2015). Understanding and defining bullying– adolescents’ own views. Archives of Public Health 73(4), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1186/2049-3258-73-4

Hill, M. (2006). Children’s voices on ways of having a voice: Children’s and young people’s perspectives on methods used in research and consultation. Childhood, 13(1), 69–89. https://doi.org/10.1177/0907568206059972

Hong, J. S., & Espelage, D. L. (2012). A review of mixed methods research on bullying and peer victimization in school. Educational Review, 64(1), 115–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2011.598917

Hughes, M. (2016). Critical, respectful, person-centred: Q methodology for educational psychologists. Educational and Child Psychology, 33(1), 63–75.

Hughes, R., & Huby, M. (2002). The application of vignettes in social and nursing research. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 37(4), 382–386. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02100.x

Hutson, E. (2018). Integrative review of qualitative research on the emotional experience of bullying victimization in youth. Journal of School Nursing, 34(1), 51–59. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059840517740192

Jacobs, N., Goossens, L., Dehue, F., Völlink, T., & Lechner, L. (2015). Dutch cyberbullying victims’ experiences, perceptions, attitudes and motivations related to (coping with) cyberbullying: Focus group interviews. Societies, 5(1), 43–64. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc5010043

Jia, M., & Mikami, A. (2018). Issues in the assessment of bullying: Implications for conceptualizations and future directions. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 41, 108–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2018.05.004

John, A., Montgomery, D., & Halliburton Tate, A. (2014). Using Q methodology in conducting research with young children. In O. Saracho (Editor): Handbook of Research Methods in Early Childhood Education, Volume 1, (pp. 147–173), University of Maryland.

Khanolainen, D., & Semenova, E. (2020). School bullying through graphic vignettes: Developing a new arts-based method to study a sensitive topic. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406920922765

Kulig, J. C., Hall, B., & Grant Kalischuk, R. (2008). Bullying perspectives among rural youth: A mixed methods approach. Rural and Remote Health, 8, 1–11.

Lyon, D., & Carabelli, G. (2016). Researching young people’s orientations to the future: The methodological challenges of using arts practice. Qualitative Research, 16(4), 430–445. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794115587393

Lundberg, A., de Leeuw, R., & Aliani R. (2020). Using Q methodology: sorting out subjectivity in educational research. Educational Research Review, 31, 100361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2020.100361

Modin, B. (2012). Beteendeproblem bidrar till utsatthet för mobbning och psykisk ohälsa. I: Skolans betydelse för barns och ungas psykiska hälsa - en studie baserad på den nationella totalundersökningen i årskurs 6 och 9 hösten 2009 behavior problems contribute to victimization from bullying and poor self-related mental health. in: The role of the school for young people’s mental health. A study based on the national Swedish survey of students in grades 6 and 9 in 2009. ( No. 2012–5–15). National Board of Health and Welfare and Centre for Health Equity Studies.

Monks, C. P., & Smith, P. K. (2006). Definitions of bullying: Age differences in understanding of the term, and the role of experience. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 24(4), 801–821. https://doi.org/10.1348/026151005X82352

O’Brien, N. (2019). Understanding alternative bullying perspectives through research engagement with young people. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1984. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01984

Patton, D. U., Hong, J. S., Patel, S., & Kral, M. J. (2017). A systematic review of research strategies used in qualitative studies on school bullying and victimization. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 18(1), 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838015588502

Pellegrini, A. D., & Long, J. D. (2002). A longitudinal study of bullying, dominance, and victimization during the transition from primary school through secondary school. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 20, 259–280. https://doi.org/10.1348/026151002166442

Punch, S. (2002). Research with children: The same or different from research with adults? Childhood, 9(3), 321–341. https://doi.org/10.1177/0907568202009003005

Queirós, A., Faria, D., & Almeida, R. (2017). Strengths and limitations of qualitative and quantitative research methods. European Journal of Education Studies, 3(9), 369–387. https://doi.org/10.46827/ejes.v0i0.1017

Scheithauer, H., Smith, P. K., & Samara, M. (2016). Cultural issues in bullying and cyberbullying among children and adolescents: Methodological approaches for comparative research. International Journal of Developmental Science 10, 3–8. https://doi.org/10.3233/DEV-16000085

Scherer, L. (2016). Children’s engagements with visual methods through qualitative research in the primary school as “Art that didn’t work.” Sociological Research Online, 21(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.5153/sro.3805

Shaghaghi, A., Bhopal, R. S., & Sheikh, A. (2011). Approaches to recruiting ‘hard to reach’ populations into research: A review of the literature. Health Promotion Perspectives, 1, 86–94. https://doi.org/10.5681/hpp.2011.009

Shemmings, D., & Ellingsen, I. T. (2012). Using Q methodology in qualitative interviews. In J.F. Gubrium, J.A. Holstein, A.B. Marvasti, & K.D. McKinney (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of interview research: The complexity of the craft (2nd ed), (pp. 415–426). Sage.

Slaughter, V., Dennis, M. J., & Pritchard, M. (2002). Theory of mind and peer acceptance in preschool children. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 20, 545–564.

Smith, P. K., Cowie, H., Olafsson, R. F., & Liefooghe, A. P. D. (2002). Definitions of bullying: A comparison of terms used, and age and gender differences, in a fourteen–country international comparison. Child Development 73(4): 1119–1133. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00461

Smith, P. K., Robinson, S., & Marchi, B. (2016). Cross-national data on victims of bullying: What is really being measured? International Journal of Developmental Science, 10(1–2), 9–19. https://doi.org/10.3233/DEV-150174

Stephenson, W. (1935). Technique of factor analysis. Nature, 136, 297.

Stephenson, W. (1953). The study of behavior: Q technique and its methodology. Chicago University Press.

Storey, K., & Slaby, R. (2013). Eyes on bullying in early childhood. Education Development Center. Retrieved from www.eyesonbullying.org

Swearer, S. M., Siebecker, A. B., Johnsen-Frerichs, L. A., & Wang, C. (2010). Assessment of bullying/victimization. The problem of comparability across studies and across methodologies. In S.R. Jimerson, S.M. Swearer, & D.L. Espelage (Eds.), Handbook of bullying in schools: An international perspective (pp 305- 328). Routledge

Sydor, A. (2013). Conducting research into hidden or hard-to-reach populations. Nurse Researcher, 20, 33–37.

Thorsen, A. A., & Størksen, I. (2010). Ethical, methodological, and practical reflections when using Q methodology in research with young children. Operant Subjectivity, 33(1–2), 3–25.

Torrance, D. A. (2000). Qualitative studies into bullying within special schools. British Journal of Special Education, 27, 16–21.

Vacchelli, E. (2018). Embodiment in qualitative research: Collage making with migrant, refugee and asylum seeking women. Qualitative Research, 18(2), 171–190. https://doi.org/10.1332/policypress/9781447339069.003.0004

Waters, E., Stewart-Brown, S., & Fitzpatrick, R. (2003). Agreement between adolescent self-report and parent reports of health and well-being: Results of an epidemiological study. Child Care Health Development, 29, 501–509. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2214.2003.00370.x

Watts, S., & Stenner, P. (2012). Doing Q methodological research: Theory, method and interpretation. Sage.

Wester, K. L., & Trepal, H. C. (2004). Youth perceptions of bullying: Thinking outside the box. Operant Subjectivity, 27, 68–83.

Woodhead, M., & Faulkner, D. (2008). Subjects, objects or participants? Dilemmas of psychological research. In P. Christensen & A. James (Eds.), Research with children (2nd ed., pp. 10–39). Routledge.

Wright, P. N. (2013). Is Q for you?: Using Q methodology within geographical and pedagogical research. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 37(2), 152–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098265.2012.729814

Funding

Open access funding provided by Malmö University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

Not applicable.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

The original online version of this article was revised: References are not in alphabetical order.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lundberg, A., Hellström, L. Q Methodology as an Innovative Addition to Bullying Researchers’ Methodological Repertoire. Int Journal of Bullying Prevention 4, 209–219 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42380-022-00127-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42380-022-00127-9