Abstract

The purpose of this classroom-based study is to understand the differences and similarities between trained peer written feedback and the teacher-researcher’s written feedback over time and identify key instructional features contributing to them. Using repeated-measures, the teacher-researcher analyzed comment area, function, feature, and type of revision-oriented comments produced by 17 trained freshmen English majors and the teacher-researcher on three writing assignments over a semester. The findings show that despite significant differences in amount and area of comments, trained peer written feedback and the teacher-researcher’s written feedback gradually resembled each other in function, feature, and type of revision-oriented comments over time. Possible factors for the increasing similarity included peer review training, teacher-student conference, provision of guiding questions, observation of the teacher-researcher’s and peer written feedback, as well as a change of the teacher-researcher’s commenting strategy.

摘要

此課室研究旨在了解受訓練後之同儕評論與教師評論之異同,並指出何種教學活動促成兩者間之異同。研究者(亦為此寫作課之教師)蒐集十七位主修英語且受過同儕評論訓練之大一學生,在學期始、中、末對同儕作文所寫之評論及研究者對相同作文所寫之評論,以重複分析法(repeated-measures),分析兩者評論之重點範圍、功能、特性、及種類。結果顯示:兩者書面評論在數量及重點範圍方面雖有顯著差異,但在功能、特性及種類三個面向,漸趨類似。促成兩者評論逐漸相似之主因為:學期始之同儕評論訓練、進行評論時教師研究者提供的引導問題(guiding questions)、教師及同儕給予自身寫作之書面評論、並與教師討論(teacher-student conference)、及學期末教師評論策略之改變。

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Peer review, an instructional practice requiring students to produce written comments to express their opinions, evaluations, and judgments about peers’ work, has gained increasing popularity among ESL/EFL writing instructors. Research has shown that, designed appropriately and implemented strategically, peer review can help students better understand the composing and revision process [13, 29], develop awareness of audience and text ownership [27], and cultivate positive attitude toward writing [14]. Evidence has also shown that ESL/EFL students, after training, develop a deeper insight into the impact of their comments [10], assume a more collaborative stance when reviewing peers’ drafts [16], are able to detect high-order issues [28] and generate revision-oriented comments [11]. Consequently, writers tend to use more trained peer written feedback in their revision [2, 7, 11, 15, 21], thus enhancing their revision quality [15, 19].

Despite the encouraging findings of ESL/EFL peer review training studies, it is unclear how trained peer written feedback is different from or similar to teacher written feedback (but see [23, 24]). Understanding the nature of trained peer written feedback and teacher feedback is important for both ESL/EFL writing researchers and teachers. This understanding can not only extend the existing knowledge about the “complementary” relationship between teacher and peer written feedback [1, 23, 24, 27, 31] but also provide EFL/EFL writing teachers with research-based evidence in deciding how to use trained peer written feedback in their writing classes—as a supplement to or a substitute for theirs during formative assessments of students’ interim drafts—to enhance student-autonomous learning. Given these reasons, the purpose of this exploratory classroom-based study is to examine differences and similarities between trained peer written feedback and teacher written feedback in an EFL writing class over a semester and to identify key instructional features that contribute to them.

Literature Review

Peer Review Training and Students’ Comments on Global Issues

A major concern of most ESL/EFL writing researchers and teachers about incorporating peer review into their classes is students’ inability to detect and comment on global issues (e.g., content and organization). However, current ESL/EFL research on peer review training has consistently shown its effect on enhancing students’ ability to detect and comment on global issues in peers’ writing [11, 21, 28]. For classroom-based studies, successful training effects have been reported in various peer review contexts [11, 14, 30]. Students, after receiving various lengths of peer review training, have been found to make significantly [21] or noticeably more comments [11] on global issues. In studies where students’ language proficiency is considered, the training effect appears more pronounced for the less proficient group than the more proficient group given that the latter was able to discern and make “various types of global revision before the online feedback training” ([30], p. 227). Quasi-experimental studies using within-subjects [21, 28] and between-subjects research designs [21] have also reported similar successful training effects. In a within-subjects design study, Van Steendam et al. [28] reported that after 6 weeks’ training, more than 4/5 of the students that did not detect higher-order issues on the pretest were able to detect, revise, and comment on significantly more global issues on the posttest. Rahimi [21], employing both between- and within-subjects research designs, found that after training, the experimental group made significantly more global comments than the control group. The results of the within-subjects comparison show that the control group made significantly more comments on language issues after traditional classroom instruction, whereas the experimental group made significantly more comments on global issues after peer review training.

To summarize, previous ESL/EFL peer review training studies have shown positive training effects on students’ ability to make comments on global issues. Yet it is unknown how trained students’ written feedback compares with the teacher’s in this regard.

Nature of Teacher and Peer Written Feedback

To the researcher’s knowledge, only five studies have focused on examining the nature of teacher and peer written feedback in depth. Two are in L1 disciplinary writing classes [4, 18]. The other three are in L2 writing classes [1, 23, 24]. A clarification of terms is necessary before reviewing these studies. Comment types refer to functions of comments, including evaluation (praise or criticism), directive, and response [4]. Comment areas refer to global (e.g., content) and local (e.g., language) issues [12].

Term Definition

Given different roles—a judge, a coach, or a reader—the teacher and peers may play while giving comments, the function of their comments—to evaluate (praise or criticize), to direct, or to respond—also varies [4, 18]. In this study, comment types refer to various functions of comments, namely evaluation (praise or criticism), directive, and response [4, 18]. Comment areas are also important indicators of students’ ability to spot different levels of writing issues in peers’ writing [4]. In the following, comment areas are categorized into global (e.g., content and organization) and local (e.g., language) issues [12].

L1 Studies

Intending to understand the nature of written feedback produced by L1 content teachers and student reviewers, Cho et al. [4] examined the on-line peer comments produced by undergraduate students, graduate students, and an expert subject teacher. The results show that the subject teacher’s comments contained significantly more idea units and were significantly longer than the undergraduates’. Regarding comment types, the content teacher produced significantly more directive comments suggesting specific changes to improve the writer’s paper than the undergraduates. The undergraduate students, on the other hand, produced significantly more praise than the content teacher.

Continuing this line of research, Patchan et al. [18] also examined types of comments generated by a subject teacher, a writing teacher, and undergraduates and further investigated two features of directive comments—description and explanation. Similar to Cho et al.’s findings, they found that (1) both teachers’ written comments were significantly longer than peers’ and that (2) peers’ comments contained significantly more praise than both teachers’. Regarding the features of directive comments that occurred frequently, they found two major significant differences. The two teachers commented on content problems twice as much as the undergraduates, but the undergraduates provided more language-related solutions than the teachers. Despite the significant differences in comment types and frequent features of directives, Patchan et al. also found eight dimensions where peer and teacher comments converged, leading them to conclude that “[L1] peer feedback seems to be quantitatively and qualitatively similar to instructor feedback” in their setting (p. 139).

L2 Studies

Unlike the two L1 quasi-experimental studies which compared students’ comments to those of teachers who were not the course instructors, ESL/EFL writing teacher-researchers have attempted to understand how their students’ written feedback differed from and resembled theirs. Caulk [1] compared his and his students’ comments on 25 students’ writing from 3 different English for academic writing classes at a university in Germany. According to his judgment, his students could provide quality feedback. Both Caulk and the students commented on similar areas. The major differences between their comments lay in scope of comments and style of making suggestions. Caulk’s feedback tended to focus on the overall issues of a whole piece, while peer feedback tended to be more oriented to specific parts of the writing. Concerning style, Caulk usually suggested revision strategies only, while the students usually made specific suggestions about how to revise the content. Caulk concluded that his and peer response served critical and “complementary functions in developing writing abilities” (p. 187).

In a similar vein, Ruegg [23, 24] compared the students’ and her written feedback to students’ writing over an academic year. Different from the previous research, Ruegg offered a 90-min training session to students to perform peer review. The results show that Ruegg produced significantly more coded marks and general comments than the trained students, whereas the trained students generated significantly more uncoded marks and specific comments [23]. Regarding comment area, although Ruegg produced significantly higher proportions of meaning-level and content feedback than the students, both Ruegg and the students generated similar proportions of written feedback in “lexis, surface-level grammar, structure, and style” ([24], p. 78). One thing needs noting is that both Ruegg’s and the students’ written feedback were mainly responses to questions generated by student writers. So the differences found in the comment areas are more of an effect of the writer’s questions than that of the nature of teacher and trained peer written feedback.

Taken together, L1 and L2 studies examining the nature of teacher and peer written feedback have validated the possibility that peer written feedback can be similar to the teacher’s in substance [1] or form [18], despite some noticeable differences in comment length, amount of ideas, and praise [4] as well as proportions of meaning- and content-level comments [24].

Issues Unaddressed

Despite the illuminating findings from previous research, our understanding is limited to the relationship between teacher written feedback and untrained L1 peer written feedback collected at a specific time point [4, 18]. Even when the data were about trained L2 peer written feedback [23, 24] or collected over a period of time [1, 23, 24], they were mediated by writer-generated questions [23, 24] or analyzed as being collected at a fixed time [1, 23, 24]. Although these analyses can help us understand the nature of teacher and untrained/trained peer comments at a specific time, they failed to shed any light on the nature of teacher and trained peer written feedback over time.

In addition, when comparing the nature of teacher and peer written feedback, most researchers have focused on comment areas and functions [1, 4, 18, 23, 24], but few focused on features of their revision-oriented directives [18] which have been shown to link to enhanced revision [6]. Given this, one focus of this study is to examine the features of revision-oriented directives in teacher and trained peer written feedback.

Purpose and Research Questions of this Study

Given that existing understanding of the relationship of teacher and peer written feedback has been predominantly premised on comparisons of teacher written feedback and untrained/little-trained peer written feedback at a fixed time point in a controlled manner, the purpose of this study is to explore the differences and similarities between teacher written feedback and trained peer written feedback in an EFL writing class at different time points over a semester. The research questions are formulated as follows.

At the beginning, mid, and end of a 16-week writing class,

-

1.

how was trained peer written feedback similar to or different from the teacher’s in comment area?

-

2.

how was trained peer written feedback similar to or different from the teacher’s in comment function?

-

3.

how was trained peer written feedback similar to or different from the teacher’s in features of revision-oriented directives?

-

4.

how was trained peer written feedback similar to or different from the teacher’s in types of revision-oriented directives?

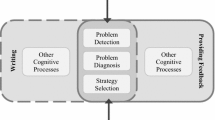

“Area” is defined as comments on global/local issues [12], and “function” is defined as evaluating, directing, responding because of the common roles—evaluator, tutor, and reader—assumed by teacher and student reviewers [4, 18]. Regarding “feature” of revision-oriented directives, Gielen et al. [6] identified two dominant perspectives on peer feedback quality. The same perspectives can be applied to teacher feedback. One dominant perspective on quality features is related to the “summative assessment” perspective—the more “number of errors… from the total number of errors” in peers’ writing can be correctly identified, justified, and corrected, the higher quality of peer feedback is. The other perspective equates feedback quality with “content and/or style characteristics” (p. 306) identified in constructive feedback offered by peers [9, 26] and experts [20]. Given the inherent difficulty of evaluating the correctness of teacher and peer written feedback on global issues [18] and the instructional nature of this study, the researcher adopted the second perspective. Following Patchan et al.’s [18] and Gielen et al.’s [6] analytical frameworks for analyzing features of revision-oriented written feedback pivotal to invoking revision, the teacher-researcher defined feature as one of the following: ask clarification questions, identify problems, explain problems, and make suggestions.

Methodology

Context of the Study and Participants

The research site was a first-year academic writing class for English majors taught by the teacher-researcher at a university in Taiwan. The class met on 2 days for 3 h per week for a total of 18 weeks. There were 17 students enrolled for this class, 3 males and 14 females, with an age average 18.3. All students’ first language was Mandarin and they had received formal English training for more than 6 years at the beginning of the study. Many (55.55%) had passed the intermediate level and some (27.78%) had passed the higher-intermediate of General English Proficiency Test, indicating that most of their language proficiency was between B1 and B2 levels in the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages, according to the Language Training and Testing Center in Taiwan. None had performed peer review before the study.

Writing Instruction

According to the instruction guidelines from the Department, the writing instructor needs to instruct basic paragraph structure (e.g., topic sentence), rhetorical patterns (e.g., narrative), language, mechanics, and peer review skills to students. Based on these guidelines, the teacher-researcher, a believer of explicit writing instruction and process- and genre-oriented approaches, followed the designed four themes to instruct students over the semester—general introduction to academic paragraphs and peer review training, as well as instructions on descriptive, example, process paragraphs—each of them lasting 1 month.

Preparation for Academic Paragraph Writing and Peer Review Training and

The teacher-researcher spent the first month building up students’ knowledge about academic paragraphs and training them to perform peer review. After the course introduction on the first day, she distributed to each student a copy of a former student’s writing and asked them to provide written feedback. The purpose of this task was to understand what feedback students could provide and how they provided it. The students’ feedback was coded by the teacher-researcher’s assistants during the second and third weeks. In the meantime, she introduced to the class basic components of an academic paragraph such as the topic, bridging, and concluding sentences and their functions. Notions such as coherence and unity were also introduced. Students were required to collaborate with one another to detect inconsistent and irrelevant examples in sample paragraphs in their textbooks, choose correct controlling ideas based on information in those paragraphs, write appropriate topic sentences containing single main ideas for those paragraphs, and restate main ideas in concluding sentences.

During the fourth week, the teacher-researcher returned to students their written comments, with each comment marked with appropriate number codes. These number codes, representing the steps of a commenting procedure that she developed based on the existing literature, ranged from 1 to 4. One means the writer’s intention was clarified; 2 means a problem was identified; 3 means an explanation was provided; 4 means a suggestion was offered. She first used PPT to explain to students these four steps to help them establish declarative knowledge. She then demonstrated how to give revision-oriented feedback by using this four-step procedure on a global issue (Appendix 1). After the demonstration, she asked students to follow the four-step procedure by adding more steps to make their feedback generated during the first week more revision-oriented. While students were revising their written feedback, she circled the class to offer help to those that had problems understanding the instruction or following the procedure. All students could add at least one more step to their comments.

Besides the 1-h in-class peer review training, the teacher-researcher also held a 15-min one-on-one conference with each reviewer about their comments on their classmates’ first draft of the first topic after class, during which she discussed with students how to improve their written feedback by following the four-step procedure. Figure 1 shows the timeline when students received in-class peer review training, had an individual teacher-reviewer conference after-class, and performed their first peer review.

Writing Cycles

The second to the fourth months are three writing cycles, with each devoted to one specific paragraph type. For the instruction on the three different paragraphs (descriptive, example, and process), the teacher-researcher employed a mixed genre and process approach. She followed the first four stages of the teaching and learning cycle—building the context, modeling and deconstructing the text, joint construction of the text, independent construction of the text—proposed by Feez [5] and espoused by the Systemic Functional Linguistic School. According to Hyland [8], this “explicit methodological model” is designed to “scaffold” students via planned and sequenced classroom activities to compose a certain type of essay genre through various stages. For the initial stage-building the context, she usually started introducing the purpose and type of a specific academic paragraph via lecture slides, with a particular focus on structural characteristics, to build up students’ declarative knowledge. She then moved on to the second stage by modeling how to analyze the sample paragraph by raising questions for “writerly engagement with text” ([3], p. 66). General questions about the reader (“Who was the target audience?”), the writer (“Who do you think wrote this paragraph”), and the writer’s purpose (“Under what kinds of situation was this paragraph written?” and “What was the writer’s purpose?”) were always raised and discussed. Questions about generic academic paragraphs were also raised, followed by those about features of a specific academic paragraph genre. Take descriptive paragraphs for example, in addition to generic questions about topic sentence, controlling idea, and so on, questions about the specific features such as sequence of description (e.g., “Can you tell how the writer described the car, from the exterior to the interior, right to left, or the front to the back?”) and use of metaphors (What did the writer compare the car to by using “roar”?) similes, adjectives, and words evoking the reader’s five senses (“What sentences make you see, hear, feel, and even smell the car?”) were raised. Students were asked to engage in pair or group discussion first and to share their answers with the whole class. By discussing answers to these questions aiming at deconstructing the text, students learned to put their declarative knowledge into practice.

After the modeling, deconstructing, and discussion, the teacher-researcher then asked students to collaborate with each other to produce an oral descriptive paragraph about a place of their department for practice to reinforce their procedural knowledge (third stage—joint construction of the text). After the instruction, students were required to independently compose their first draft over the weekend and brought it to class for face-to-face peer review the following week (independent construction of the text). During the second week, the researcher-instructor explained the peer review questions about the descriptive paragraph generated by her as well as reviewed the four-step procedure on lecture slides. She then asked students to perform peer review. Each student was required to review two peers’ writing in class. The teacher-generated peer review questions, corresponding to the instructional foci about paragraph structure and features of the specific paragraph genre, highlighted global issues mostly (Appendix 2). Students were required to carefully consider peer review comments, discuss them with their reviewers in class, revise their first draft at home, and submit their first revision in word document file to an online system Moodle for the teacher-researcher’s feedback. The teacher-researcher used the review function to type up her comments, e-mailed them to students before having an individual conference with each (the third and fourth weeks of the second month). After discussing with the instructor-researcher, students needed to submit a second revision and a reflection the following week. Table 1 shows instructional procedures and activities of each week in each writing cycle.

Data Collection Procedure

The research assistants collected three types of data—teacher and peer written feedback on the first draft of each topic and students’ reflection journals. The teacher-researcher produced 17 reviews for each time. For peer written feedback, 30 reviews were produced by 15 students for the descriptive paragraph on the 6th week and another 30 reviews for the example paragraph on the 11th week. Twenty reviews produced by 10 students for the process paragraph on the 16th week. In addition, students’ were required to produce five journal entries during the semester, detailing their response to and reflections on peer comments, teacher feedback, instructional activities, and writing issues. Altogether, there were 90 entries collected. One thing needs mentioning is that the teacher-researcher read peers’ written feedback only on the first draft of the descriptive paragraph for conferencing with each reviewer. It was not until she finished commenting on the first draft did she read the students’ comments. Also, she did not read students’ comments on later topics until she finished hers and the research assistants typed up all peer written feedback for coding.

Data Coding

Both the teacher-researcher and students numbered the location of each comment they made in the writer’s text (students wrote their comments on a separate sheet) so it is easy for the research assistants to identify each comment and calculate the total. After identifying each comment, they began to code each comment for area, function, and feature, respectively.Footnote 1

Area

The unit of analysis for area is each comment. Two areas—global and local—were identified. Comments related to vocabulary use, grammar, punctuation were coded as local issues, and those related to idea development, relevancy, organization, and coherence were coded as global issues (Table 2).

Function

The unit of analysis for function is each comment. There were three types of function identified—evaluation, revision-oriented comments, response. Evaluation was further divided to criticism and praise (Table 3).

Feature of Revision-Oriented Comments

The unit of analysis for feature of revision-oriented comments is a sentence or a group of sentences comprising one or more of the following elements—clarification, problem, explanation, and suggestions. A comment can be consisted of sentences related to only one feature or multiple features. Sentences that ended with a question mark were coded as “clarification,” and those that contained a description of a problem were coded as “problem.” Sentences that offered self or dictionary explanations were coded as “explanations,” and sentences that began with “I suggest/recommend/guess...” and “Maybe you can...” and are followed by suggestions were coded as “suggestions.” Table 4 illustrates the breakdown of a revision-oriented comment comprising all four features.

Type of Revision-Oriented Comments

As mentioned previously, a revision-oriented comment may be consisted of one to four features. For example, a revision-oriented comment comprising three features, there are three possible types—(1) clarification, problem, and explanation; (2) clarification, problem, and suggestion; and (3) problem, explanation, and suggestion. For all documented types of revision-oriented comments, see Table 8.

Rater Training and Inter-Rater Reliability

One doctoral and one M.A. student who have worked with the teacher-researcher for 3 years coded the data. The teacher-researcher held a training session during which she explained and demonstrated how to code a student’s comment, let the two assistants code three students’ comments individually, and then compared their coding results with hers. After the training, the two assistants separately coded the teacher-researcher’s and the students’ feedback. Differences were discussed among the two coders first. If they could not reach an agreement, the teacher-researcher then served as the third coder. A code agreed by two of the three raters served as the final code, and this instance was counted as a disagreement. The interrater reliability for the students’ feedback was .87, and for the teacher-researcher’s was .91.

Data Analysis

The analysis is mainly a quantitative one supplemented with qualitative data. A 2*3 repeated-measure with teacher and trained peer written feedback as the between-group factor and time as the within-group factor was run for each comment area, function, feature, and type. Given that only one writing instructor, but two student reviewers, reading each paragraph, the teacher-researcher followed Patchan et al.’s [18] method by treating each review produced by the teacher-researcher and students (rather than the number of teacher and student participants) as “the object of variability” (p. 133). For example, for the first research question, she calculated the mean of each comment area in the teacher-researcher’s written feedback to each student’s draft, and that of each area per student review for descriptive, example, and process paragraphs on the 6th (time 1), 11th (time 2), and 16th week (time 3), respectively.

Results

Comment Area

Significant differences were observed in the comment area between the teacher-researcher’s and trained peer written feedback. For comments on the global issues, a significant group*time interaction effect (F(2,48) = 15.72, p < .001, eta2 = .381), group effect (F(1,24) = 46.16, p < .001, eta2 = .658), and time effect (F(2,48) = 14.78, p < .001, eta2 = .396) were found. As shown in Table 5, the teacher-researcher made significantly more comments on global issues than the students in each review. But the difference decreased significantly over time.

For comments on the local issues, a significant group*time interaction effect (F(2,48) = 17.53, p < .001, eta2 = .422), group effect (F(1,24) = 159.67, p < .001, eta2 = .713), and time effect (F(2,48) = 12.95, p < .001, eta2 = .351) were also found. The teacher-researcher made significantly more comments on local issues than the students in each review. Again, this difference decreased significantly over time.

Table 5 also shows different compositions of the teacher-researcher’s and the students’ written feedback. The teacher-researcher produced almost twice as much written feedback to local issues as she did to global issues at each time, whereas the students produced a relatively equal amount of written feedback on both issues at each time.

Comment Function

Table 6 shows that the teacher-researcher’s and students’ written feedback exhibited a similar pattern, with directives being the dominant function and other functions occurring infrequently. The repeated-measures show significant differences in directives, praise, and reader response between the teacher-researcher’s and students’ written feedback. Regarding directives, a significant group*time interaction effect (F(1,48) = 33.53, p < .001, eta2 = .583), a significant group effect (F(1,24) = 71.10, p < .001, eta2 = .876), and a significant time effect (F(2,48) = 26.23, p < .001, eta2 = .522) were observed. The teacher-researcher generated significantly more directives than the students across time, but this difference also decreased significantly over time.

Regarding the remaining two infrequent functions—praise and reader response, there was a significant group effect, respectively. The teacher-researcher made significantly more praise (F(1,24) = 19.16, p < .001, eta2 = .444) and reader response (F(1,24) = 10.92, p < .001, eta2 = .394) than the students across time.

Feature of Revision-Oriented Comments

Given that a predominant number of the teacher-researcher’s and students’ comments is revision-oriented directives, the teacher-researcher then focused on examining the features and types of these revision-oriented comments in research questions 3 and 4.Footnote 2 The repeated measures show a significant main group effect for “clarification” (F(1,23) = 5.812, p < .05, eta2 = .202), indicating that the teacher-researcher’s revision-oriented comments registered the feature “clarification” significantly more frequently than the students’ in each review across time. In addition, a significant group*time interaction effect (F(2,46) = 3.909, p < .05, eta2 = .145) and a main group effect (F(1,23) = 32.092, p < .001, eta2 = .583) were found for “suggestion.” Figure 2 shows that although the students’ revision-oriented comments registered the feature “suggestion” significantly more frequently than the teacher-researcher’s at time 1, this significant difference gradually decreased at times 2 and 3. For the other two features (“problem” and “explanation”), no significant differences were observed (Table 7).

Types of Revision-Oriented Comments

Table 8 shows the ratio of each type of revision-oriented comments per review. To find out (1) which types characterized the teacher-researcher’s and students’ comments, respectively, and (2) whether these types were similar or different, the teacher-researcher looked at the three most frequent types that comprised close to/more than half of her and the students’ written feedback at each time.

The results show that more similarities than differences were observed for types of revision-oriented comments produced by both parties as time passed. Two pieces of evidence show this trend. First, among the three most frequent types that characterized the teacher-researcher’s and the students’ revision-oriented comments respectively, only one type overlapped at time 1 (“suggestion”). But two types overlapped at time 2 (“suggestion” and “problem, explanation, suggestion”) and time 3 (“suggestion” and “problem, explanation”).

Second, among the most frequent types that characterized the teacher-researcher’s and the students’ directives, only two types were significantly different over the semester. A significant group effect was found for “clarification” (F(1,23) = 8.963, p < .01, eta2 = .280) and another significant group effect was found for “problem, suggestion” (F(1,23) = 5.356, p < .05, eta2 = .189). These results suggest that the teacher-researcher asked “clarification” questions significantly more frequently than the students across time, but the students identified “problems” and made “suggestions” significantly more frequently than the teacher-researcher.

For the remaining four types, a significant group*time interaction effect was found for “suggestion” (F(2,46) = 4.505, p < .05, eta2 = .164). Figure 3 shows that the significant difference observed at time 1 gradually decreased over time. A significant time effect was found for “problem, explanation” (F(2,46) = 5.04, p < .05, eta2 = .180), suggesting that both the teacher-researcher’s and the students’ directives registered this type of comment significantly more frequently across time. No significant difference was found for “problem, explanation, suggestion” and “clarification, suggestion.”

Discussion

Intending to explore the differences and similarities between teacher and trained peer written feedback, this study examined the teacher-researcher’s and her students’ written feedback in an EFL writing class at three time points over a semester. The results show that the teacher-researcher’s and trained students’ written feedback both differed from and shared commonality with each other over time. Although significant differences existed in the total of comments, the relative focus on comment areas, and some features and types of directives throughout the semester, other initially significant differences in features and types of revision-oriented comments disappeared at the end of the semester. Possible factors for these findings and their significance are discussed as below.

Consistent Difference in Relative Focus on Comment Area across Time

The teacher-researcher provided significantly more written feedback on both global and local issues in each review than the students across time. Her feedback on local issues was 1.5 to 2 times more than that on global issues. This result is interesting but not surprising as previous researchers have also reported that L2 writing teachers generated more written feedback on local issues [17, 31]. One main reason for the greater percentage of those L2 writing teachers’ comments on local issues was that they wanted to avoid repeating in their written feedback what they have discussed with students during teacher-student conference [17]. By contrast, the Department’s guidelines for writing instruction and the teacher-researcher’s implicit perceptions about the importance of precise language use in academic writing may have been two possible reasons. Given that language and mechanics were stipulated as two major course objectives by the Department for first-year writing classes, the teacher-researcher may have felt obligated to fulfill this requirement. Also, the teacher-researcher’s implicit perceptions about specific language use may also have played a role. Although the teacher-researcher did not keep a reflection journal about her perceptions/beliefs about providing feedback on language issues, two of the guiding questions she prepared for students during peer review shed some light on her emphasis on students’ use of specific language and varied diction (see the 5th and 9th questions in Appendix 2). Similar to Caulk [1] that prioritized the “how” issue (how you say it) in academic written communication (p. 185), the teacher-researcher also appeared to consider it essential to use precise language to express ideas in academic writing.

In contrast, the students generated a more balanced amount of comments on global and local issues. The following students’ reflection journal entries suggested two possible reasons. One is the peer review training, and the other, the guiding questions provided to them during each peer review.

Since I haven't had any experience of reviewing others' writing, I found it very difficult and complex for me as a beginner. I remember that I was only able to point out some misspelled words, instead of making any helpful suggestion at the first time. However, following the instructions help to drag me out of the awkward situation. I can make comments on content and organization now."

"Emily's instruction at the beginning of the semester and also before we're going to make the comments are really helpful to lead us to be a good reader, for it clearly gives us a way to how to make comments based on the questions Emily gave us.

The two excerpts lend support to findings in L1 [28] and L2 [21] research that novice reviewers seldom commented on global issues before instructional intervention but could do so after receiving explicit training or guidelines.

Consistent Similarity in Patterns of Comment Functions Across Time

The teacher-researcher’s and the students’ written feedback displayed a consistently similar pattern of functions across time, with the revision-oriented directives being the predominant one. It is possible that peer review training, specific guiding questions, and teacher/peer modeling may have contributed to students’ generation of greater numbers of revision-oriented comments than praise in the current study. First, the four-step commenting procedure is geared toward finding what needs revising in peers’ writing rather than what deserves praise, thus probably orienting the students to offer more revision-oriented comments. In addition, the guiding questions provided to students during each peer review were aimed to direct student reviewers’ attention to global issues and to prompt them to help improve peers’ writing. Finally, the teacher-researcher’s and peers’ comments might have also exerted some influence. Their mostly revision-oriented directives might have served as a model for students to emulate when performing peer review.

This finding differs from previous L1 research on discipline writing. Those studies have repeatedly shown that L1 undergraduate students tended to offer much more praise than both content and writing teachers, who tended to offer much more revision-oriented directives [4, 18]. Although the L1 researchers also provided students with clear and detailed guidelines to identify problems and offer feedback ([4], p. 291; [18], pp. 147–149), they did not provide specific step-by-step peer review training, require students to address guiding questions during peer review, or model how to address them. Without receiving explicit training, specific requirement to follow guiding questions to evaluate peers’ writing, and opportunities to observe how the writing teacher-researcher made comments, the L1 students may have used their own “comment-giving script” that entailed praise ([4], p. 276) or relied on their own perception that students appreciated praise [18]. The on-line tutorials, instructing students to give “praise-oriented advice for strength that made the writing good” ([18], p. 147), also appeared to reinforce these students’ comment-giving scripts and perceptions, thereby prompting them to generate a significantly greater number of praise than the instructor(s).

In fact, students in this study also had a script for giving comments before receiving peer review training—offering grammar corrections. Almost all students focused on correcting grammar mistakes when they were asked to give comments on the former student’s writing at the beginning of the semester. In a sense, the peer review training, guiding questions, and observation of the instructor’s comments on their own writing may have helped them expand their limited repertoire of commenting skills to include revision-oriented feedback to global issues. The following testimonies from students’ journal entries supported this interpretation:

At the beginning of this semester, I always care about the grammar problems. But with the training and your comments, I understood that the more important thing is to focus on the structure problem...

More Similarity in Features and Types of Revision-Oriented Comments over Time

Lastly, more similarities were observed in features and types of revision-oriented comments between the teacher-researcher and her students as time passed. Regarding features, an initially significant ratio difference in “suggestion” gradually decreased between the teacher-researcher’s and her students’ comments despite a consistent ratio difference in “clarification.” A possible explanation for the increasing similarity in “suggestion” is a change in the teacher-researcher’s commenting strategy at time 3. The teacher-researcher asked more “clarification questions” at time 1 and time 2 than she did at time 3. The following are examples of “clarification” at time 1 and time 2.

From the following description, this frame is not very special. Do you mean that you have a picture frame 'that has a special meaning to you?

Are you saying that reading is 'food to your soul?

At time 3, perhaps due to time constraint, she just offered a direction for further revision.

You need to tell the reader how to be persevere by using some concrete steps.

A closer look at the clarification questions reveals that, besides ascertaining intentions, specific suggestions were also couched in these clarification questions. Had the teacher-researcher marked most of these suggestions with a period rather than implicated them with a question mark, they would have been coded as “suggestions.” Much fewer ratio differences in “clarification” and “suggestion” would have been found, and the distribution of these two features in both parties’ revision-oriented comments would have become much more similar across time.

In contrast, the proportions of the four features of students’ revision-oriented comments collectively did not seem to change much across time, with the predominant feature being “suggestion.” But this does not mean that each individual student’s revision-oriented comments did not change, as there were two student reviewers for each paragraph. Further case studies are needed to trace how each individual’s comments (not) changed over time.

Regarding types of revision-oriented comments, there was more overlap among the three most frequent types of the teacher-researcher’s and her students’ revision-oriented comments (i.e., “problem, explanation,” “problem, explanation, suggestion”) and less difference in ratios among them as time went by (i.e., “suggestion”). What is noticeable is that an explanation was present in students’ three most frequent types of comments (e.g., “problem, explanation, suggestion” at time 1 and 2; “problem, explanation” at time 3). Explaining the nature of identified problems involves using relevant and coherent reasoning and logic. Previous research has shown that the feature of explanation in peers’ comments can predict secondary school students’ writing performance [6]. Evidence has also shown that peer tutors producing explanations for problems raised by tutees not only “benefits tutees by exposing them to more and deeper ideas” but also helps tutors “[self-]monitor their own understanding” about issues under discussion ([22], p. 343). In light of these findings, it seems possible that these trained students’ explanations in their revision-oriented comments can also help their classmates revise the identified problems and assist themselves in building up their knowledge. Further research is needed to examine this prediction though.

Conclusion

The purpose of this classroom-based study is to understand the similarities and differences of a writing teacher-researcher’s written feedback and trained peer written feedback in an EFL writing classroom. The findings show that despite significant differences in amount and area of comments, trained peer written feedback gradually shares more similarity with the teacher-researcher’s in features and types of revision-oriented comments over time.

Different from previous control studies treating teacher and peer written feedback as two separate phenomena that never intersect, this study is the first attempt in L2 writing research to systematically examine the relationship of teacher and trained peer written feedback in the writing classroom at different points in time. This alternative perspective not only documents gradual similarities between teacher and trained peer written feedback but also illuminates possible factors contributing to these similarities. The finding that trained peer written feedback gradually shares more commonality with the teacher-researcher’s suggest that it is time to reexamine the existing conception about the complementary relationship between teacher and peer feedback [1, 27, 31]. This study shows that carefully planned instructional interventions can gradually change this complementary relationship to a partially overlapping relationship in terms of comment functions, features, and types of revision-oriented comments. Further research is needed to examine if this partially overlapping relationship will converge or diverge in the future.

What are pedagogical implications of this partially overlapping relationship for ESL/EFL writing teachers? For those who still see what is wanting in trained peer written feedback can continue to help further students’ commenting skills, for example, by discussing their own commenting strategies with students. In this study, the teacher-researcher’s strategy for ascertaining the writer’s intentions via reformulations can serve as a less face-threatening commenting strategy for students to indicate confusion/perceived problems and offer direct suggestions. When students are explicitly introduced to the commenting strategies of their teachers, they can not only expand their commenting repertoire but also understand how to respond to the teacher’s use of similar strategies.

For those who see the potential of gradual similarities between trained peer written feedback and teacher written feedback can consider substituting trained peer written feedback for teacher written feedback for students’ interim drafts during formative assessment of students’ writing. ESL/EFL writing teachers constantly grapple with insufficient time to offer writing instruction, conduct peer review, give written and oral feedback to students’ interim drafts, and evaluate their written products. Replacing teacher written feedback with trained peer written feedback that registers similar quality features for students’ interim drafts can help save the teacher’s time for other instructional activities (e.g., conferencing) and reduce ESL/EFL students’ reliance on the writing teacher’s written feedback in the process of writing and encourage their autonomy in seeking answers on their own or negotiating solutions with their peers. Research has shown that EFL students’ mindful reception of peer feedback [31] and use of teacher written feedback without understanding [32] can both enhance their revision quality. From a student-learning perspective, it seems that the former is more desirable. Undoubtedly, the decision over substituting trained written peer feedback for ESL/EFL teacher written feedback for students’ interim drafts is a complex one involving serious consideration of issues of trust, personal interaction, and validity [25]. This study provides some evidence for its validity in terms of quality features of revision-oriented comments.

Given the exploratory nature of this classroom-based research, the findings of this study cannot be generalized to other writing contexts. Because this study was conducted in an intact class where the writing teacher was also the researcher, it is possible that she may have inadvertently changed her behavior (e.g., making more comments) than she usually did despite her effort to maintain objectivity in coding data. Also, the influence of teacher-researcher’s feedback and peer written feedback was not separated from the explicit in-class peer review training and after-class teacher-reviewer conference. Future qualitative studies are needed to understand how each shapes students’ written feedback. Regardless, the findings of this study not only extend Patchan et al.’s conclusion that “under certain conditions, students provide comments that are similar in both quantity and quality to those of instructors (p.143)” to an EFL writing class but also identify some key features of these conditions-explicit training of students in performing peer review, individual conferences with reviewers, and provision of guiding questions—as well as some possible features like the writing teacher’s own adherence to the commenting procedure. Interested writing teacher-researchers are encouraged to apply these identified key instructional principles to their own writing classes to see if these instructional principles also help make their students’ written feedback share similarity with theirs and if yes, further consider how they can best use trained peer written feedback to facilitate their teaching and student learning.

Notes

The teacher-researcher treated the three taxonomies—area, function, and feature—separately and calculated the number of comments according to the categories of each taxonomy independently. For comment area, the focus is on the comparative number of local versus global issues. For comment function, she did not further distinguish local from global issues because her intention was to understand the overall picture of the functions of the teacher-researcher’s and peers’ feedback. A further breakdown of the various functions under global issues (global: praise/criticism, directive, response) and local issues (local: praise/criticism, directive, response) appeared unnecessary. With these separate coding schemes, one comment belongs to only one category within each taxonomy.

The results of research questions 1 and 2 show a similar pattern regarding the ratios of revision-oriented directives to the total comments between the instructor and the students. So the researcher decided to use the ratios as the base of comparison to examine research questions 3 and 4, while acknowledging that more significant differences in absolute numbers could have been found.

References

Caulk, N. (1994). Comparing teacher and student responses to written work. TESOL Quarterly, 28, 181–188.

Chang, C. (2014). Writer's decision-making process and revision behaviors in L2 peer review. In R. C. Tsai & G. Redmer (Eds.), Language, culture, and information technology (pp. 165–192). Taipei: Bookman.

Cheng, A. (2008). Analyzing genre exemplars in preparation for writing: the case of an L2 graduate student in the ESP genre-based instructional framework of academic literacy. Applied Linguistics, 29, 50–71.

Cho, K., Schunn, C. D., & Charney, D. (2006). Commenting on writing: typology and perceived helpfulness of comments from novice peer reviewers and subject matter experts. Written Communication, 23(3), 260–294.

Feez, S. (1998). Text-based syllabus design. Sydney: NCELTR, Macquarie University.

Gielen, S., Peeters, E., Dochy, F., Onghena, P., & Struyven, K. (2010). Improving the effectiveness of peer feedback for learning. Learning and Instruction, 20, 304–315.

Hu, G., & Lam, S. T. E. (2010). Issues of cultural appropriateness and pedagogical efficacy: exploring peer review in a second language writing class. Instructional Science, 38, 371–394.

Hyland, K. (2007). Genre pedagogy: language, literacy and L2 writing instruction. Journal of Second Language Writing, 16, 148–164.

Kim, M. (2005). The effects of the assessor and assessee's roles on preservice teachers' metacognitive awareness, performance, and attitude in a technology-related design task. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Florida State University, Tallahassee, USA.

Lam, R. (2010). A peer review training workshop: coaching students to give and evaluate peer feedback. TESL Canada Journal, 27(2), 114–127.

Liou, H. C., & Peng, Z. Y. (2009). Training effects on computer-mediated peer review. System, 37, 514–525.

Liu, J., & Sadler, R. W. (2003). The effect and affect of peer review in electronic versus traditional modes on L2 writing. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 2, 193–227.

Mendonca, C. O., & Johnson, K. E. (1994). Peer review negotiations: Revision activities in ESL writing instruction. TESOL Quarterly, 28(4), 745–769.

Min, H. T. (2005). Training students to become successful peer reviewers. System, 33(2), 298–308.

Min, H. T. (2006). The effects of trained peer review on EFL students’ revision types and writing quality. Journal of Second Language Writing, 15(2), 118–141.

Min, H. T. (2008). Reviewer stances and writer perceptions in EFL peer review training. English for Specific Purposes, 27(3), 285–305 SSCI.

Montgomery, J., & Baker, W. (2007). Teacher-written feedback: student perceptions, teacher self-assessment, and actual teacher performance. Journal of Second Language Writing, 16(2), 82–99.

Patchan, M. M., Charney, D., & Schunn, C. D. (2009). A validation study of students' end comments: comparing comments by students, writing instructor, and a content instructor. Journal of Writing Research, 1, 124–152.

Paulus, T. M. (1999). The effect of peer and teacher feedback on student writing. Journal of Second Language Writing, 8(3), 265–289.

Prins, F., Sluijsmans, D., & Kirschner, P. A. (2006). Feedback for general practitioners in training: quality, styles, and preferences. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 11, 29–303.

Rahimi, M. (2013). Is training student reviewers worth its while? A study of how training influences the quality of students’ feedback and writing. Language Teaching Research, 17, 67–89.

Roscoe, R. D., & Chi, M. T. H. (2008). Tutor learning: the role of explaining and responding to questions. Instructional Science, 36, 321–350.

Ruegg, R. (2015a). Differences in the uptake of peer and teacher feedback. RELC Journal, 46(2), 131–145.

Ruegg, R. (2015b). The relative effects of peer and teacher feedback on improvement in EFL students’ writing ability. Linguistics and Education, 29, 73–82.

Sadler, D. R. (1998). Formative assessment: revisiting the territory. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy and Practice, 5, 77–84.

Sliujsmans, D. M. A., Brand-Gruwel, S., & Van Merrienboer, J. J. G. (2002). Peer assessment training in teacher education: effects on performance and perceptions. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 27, 443–454.

Tsui, A. B. M., & Ng, M. (2000). Do secondary L2 writers benefit from peer comments? Journal of Second Language Writing, 9(2), 147–170.

Van Steendam, E., Rijlaarsdam, G., Sercu, L., & Van den Bergh, H. (2010). The effect of instruction type and dyadic or individual emulation on the quality of higher-order feedback in EFL. Learning and Instruction, 20, 316–327.

Villamil, O. S., & de Guerrero, M. C. M. (1996). Peer revision in the L2 classroom: social-cognitive activities, mediating strategies and aspects of social behavior. Journal of Second Language Writing, 3, 51–75.

Yang, Y. F., & Meng, W. T. (2013). The effects of online feedback training on students’ text revision. Language Learning & Technology, 17, 220–238.

Yang, M., Badger, R., & Yu, Z. (2006). A comparative study of peer and teacher feedback in a Chinese EFL writing class. Journal of Second Language Writing, 15, 179–200.

Zhao, H. (2010). Investigating learners' use and understanding of peer and teacher feedback on writing: a comparative study in a Chinese English writing classroom. Assessing Writing, 15, 3–17.

Acknowledgments

This study is partially supported by grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan, Republic of China (MOST 103-2410-H-006-101-, 104-2410-H-006-060). I would like to thank the two research assistants, Wendell Wang and Jeffery Lin, for their assistance in coding and analyzing the data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1

Student writing: And what I learned to see in such a confusing world was to trust your friend, although his or her words seemed useless!

Application of the four-step procedure:

-

Step 1

You want the writer to explain “an unclear part” in her or his writing.

-

Your feedback will read like the following:

-

“What do you mean by ‘useless’”?

-

“Useless?” I do not get this.

-

“Why did you think that your friends’ words were ‘useless’”?

-

-

Step 2

You point out a problematic word, phrase or sentence or cohesive gap.

-

Your feedback will read like the following:

-

“The word ‘useless’ does not seem to make sense.

-

-

Step 3

You explain why an idea (word, phrase, connection) is problematic or unclear. Your feedback will read like the following:

-

“If her words had been ‘useless,’ could you have completed your task on your own in a blindfold?

-

Step 4

You suggest ways to change the words, content, and organization of essays.

-

Your feedback will read like the following:

-

“Maybe you can say that “although her words may have appeared less useful then.”

-

Appendix 2 Guiding Questions for the Descriptive Paragraph

-

1.

Is there a topic sentence at the beginning of the paragraph?

-

2.

Does the topic sentence contain a controlling idea?

-

3.

If you cannot find a topic sentence, drawing on what you have read, summarize your ideas in one sentence and ask the author to think about it.

-

4.

Did the author provide background to the possession?

-

5.

Did the writer provide details to help you imagine how the possession looks, feels, sounds, tastes, or smells?

-

If yes, are the details written in specific language?

-

6.

Are all the details related to the possession?

-

7.

Are the details connected in a logical manner?

-

8.

Did the writer associate the possession with any memories or feelings?

-

9.

Is there a concluding sentence at the end of the paragraph, summarizing the controlling idea of the topic sentence?

-

If yes, is this restatement rephrased with different vocabulary to avoid repetition? If not, make a suggestion.

-

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Min, HT. Trained Peer Written Feedback and Teacher Written Feedback: Similar or Different?. English Teaching & Learning 42, 131–153 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42321-018-0009-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42321-018-0009-1