Abstract

Introduction

Real-world use of immunomodulating therapy (IMT) in patients with systemic sclerosis (SSc) was investigated for the first time in a descriptive, retrospective cohort analysis of claims made in a healthcare insurance database to characterize treatment patterns and their alignment with SSc disease manifestations.

Methods

Treatment patterns and disease manifestations, symptoms, complications, and comorbidities were assessed in patients with SSc enrolled in a US healthcare claims database who received treatment between January 2006 and December 2013 and for whom data were available 6 months before and 12 months after SSc diagnosis.

Results

Among 7812 eligible patients, 6852 received treatments of interest for SSc and 2404 (30.8%) received IMT during the first year after SSc diagnosis. In the first year after diagnosis, the most common claims were for antibiotics (61.7%), opioids (50.6%), glucocorticoids (46.5%), and proton pump inhibitors (35.4%); the most common organs involved with complications among patients with SSc were lung (30.5%), heart (17.4%), and gastrointestinal tract (22.4%); the most common signs or symptoms were musculoskeletal (16.1%) and fatigue (10.5%); 1035 patients (15.1%) had infections and 14 (0.2%) had malignancies. Among patients who received IMT, 43.8% received at least hydroxychloroquine and 21.1% received at least methotrexate; 460 patients switched to a second IMT, 23.0% to at least methotrexate and 22.8% to at least mycophenolate mofetil. The most common comorbidities reported with first IMT were in lung (11.8%), overlap syndrome (8.4%), heart (5.3%), and gastrointestinal (6.8%) categories.

Conclusion

One-third of patients with SSc in the healthcare claims population received IMTs during the first year after diagnosis. However, patients who received IMTs had disease manifestations similar to those of the overall SSc healthcare claims population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Treatment options for patients with systemic sclerosis (SSc) are limited to management of disease manifestations in organs; however, real-world use of immunosuppressive treatments has not been investigated. |

This retrospective cohort analysis of claims made in a US healthcare insurance database investigated treatment patterns for immunomodulating therapies received in the first year after diagnosis of SSc and their alignment with organ manifestations. |

The most common SSc organ manifestations reported were in the lung, gastrointestinal tract, and heart, but only one-third of patients with diagnoses of SSc received immunomodulating therapy in the first year after diagnosis. |

Among the patients who received immunomodulating therapy, the most common comorbidities reported with their first treatment were in the lung, overlap syndrome, heart, and gastrointestinal categories. |

Disease manifestations reported in patients who received immunomodulating therapies were similar to those of the overall SSc healthcare claims population, suggesting that patients treated with immunomodulating therapy did not exhibit unique organ manifestations compared with those who did not receive immunomodulating therapy. |

Introduction

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is a vascular and connective tissue autoimmune disorder characterized by inflammation and fibrosis [1]. The clinical presentation of SSc is heterogeneous. Symptoms include Raynaud’s phenomenon and skin sclerosis; in more severe cases, the disease may affect multiple internal organs [1]. Commonly affected organs include the pulmonary vascular system, heart, gastrointestinal tract, skin, lungs, and kidneys [1]. Pulmonary, cardiac, and renal manifestations are the most severe manifestations, with pulmonary and cardiac complications the leading causes of death related to SSc [1, 2].

In the USA, the estimated annual incidence of new cases of SSc ranges from 0.6 to 63.0 cases per million adults, and the estimated prevalence ranges from 4.0 to 286.0 cases per million adults [3,4,5]. Similar incidence and prevalence have been reported in Australia and Spain, with an incidence of 22.8 and 23 cases per million population and a prevalence of 233 and 277 cases per million population, respectively [6, 7]. The epidemiology of SSc in Europe varies widely; the reported prevalence ranges from 7 to 489 per million population and the incidence ranges from 0.6 to 122 per million population [8,9,10,11,12]. Rates of SSc are lower in northern Europe than in southern Europe as assessed using similar methodologies, suggesting some populations in Europe may be more susceptible based on genetic or environmental differences [12]. In general, geographic differences between the USA and Europe in estimates of SSc may signal methodological differences in case ascertainment and definitions or may be true geographic differences [3].

Treatment options for patients with SSc are limited to the management of disease manifestations in organs. Although trials have been conducted, no treatment has yet been approved for patients with SSc [13]. European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) and British Society for Rheumatology/British Heath Professionals in Rheumatology (BSR/BHPR) guidelines include recommendations for immunosuppressive treatment with methotrexate (MTX), cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), and stem cell transplantation for the treatment of skin or lung manifestations [14, 15]. Clinical trial results of MTX suggested improvement of skin sclerosis, but the improvement with MTX versus placebo was not statistically significant [16]. Randomized controlled trials suggested that cyclophosphamide may improve lung function in patients with SSc interstitial lung disease (ILD) [17, 18]; however, cyclophosphamide is associated with safety risks. The efficacy of MMF appears to be similar to that of cyclophosphamide for the treatment of skin and lung fibrosis in established SSc-ILD [19]. Stem cell transplantation is another potential treatment option for patients with very severe SSc-associated complications [20, 21], but it is associated with increased risk for early death [21]. MTX, corticosteroids, and hydroxychloroquine have been used for the treatment of SSc-related inflammatory arthritis [22].

Real-world use of immunosuppressive treatments in patients with SSc has not been investigated. Therefore, this study was conducted to facilitate understanding of common treatment patterns in a large population of patients with SSc and to investigate how, using a descriptive, retrospective cohort analysis of claims made in a US healthcare insurance database, disease manifestations align with treatments received.

Methods

Study Design and Patients

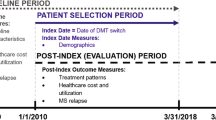

This was a retrospective cohort study using data obtained from the Truven Health MarketScan® Research Databases. Eligible patients were adults (at least 18 years old) who were receiving treatment for SSc, received care between January 1, 2006, and December 31, 2013, and had enrollment data 6 months before and 12 months after the SSc diagnosis index date, which ensured continuous medical and pharmacy coverage. The diagnosis index date was defined as the first SSc diagnosis during the study period, and enrollment gaps of at most 30 days before the index date were permitted. An SSc diagnosis was defined as at least one inpatient claim for an SSc diagnosis according to the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) or at least two outpatient claims at least 7 days apart for an SSc diagnosis. Data were assessed at 1 year of follow-up from diagnosis. This study only used de-identified patient data from a database; therefore, ethics committee approval and informed consent were not needed.

Treatment Assessments

To evaluate treatment patterns, treatments of interest were grouped on the basis of a combined approach that applied clinical knowledge of treatments that were expected to be observed a priori and a data-driven approach to rank the most common treatments among patients with SSc (Supplementary Appendix 1). Treatments were determined in the 6 months before the study period and during the entire study period after the diagnosis of SSc. The first IMT administration on or after the index date was defined as the start of a drug in the IMT group (Supplementary Appendix 1); this treatment was followed until the end of the prescription course, including refills. Combination IMT therapy was permitted during treatment with the first IMT if a different IMT was initiated during and within 90 days after the start of initial treatment. A switch to a second IMT was made when a new IMT was initiated (and was not used as part of combination therapy while the patient was receiving treatment with the first IMT) after the end of the previous IMT or 90 days after start of the first IMT. IMT combinations were also permitted during second IMT therapy. Secondary treatments such as antibiotics, opioids, and glucocorticoids (Supplementary Appendix 1) were identified if there was a fill while the patient was receiving IMT therapy.

SSc disease manifestations, symptoms, complications, and coexisting conditions were also captured on the basis of medical billing codes used in insurance claims to document diagnoses that were made during patient visits (patients had at least two SSc diagnosis codes). SSc symptom categories from the literature, ICD-9 general disease categories, and the top-ranked individual diagnoses found in the data were used to aggregate diagnoses into 20 categories over the course of 1 year from the SSc diagnosis index date. Comorbidities (Supplementary Appendix 2) were determined in the 180 days before and during the entire time frame of eligibility following the diagnosis of SSc.

Results

Study Population and Patient Demographics

A total of 73,124 patients with SSc were identified between 2006 and 2013 in the MarketScan database (Fig. 1). Among 7804 patients with any treatment who met the eligibility criteria for this study, 6852 received valid treatments and 2404 received IMTs. From 2006 to 2013, the prevalence of SSc in the MarketScan database ranged from 204 to 248 cases per million adults who were actively enrolled in health insurance plans (Supplementary Fig. S1). Patients were enrolled in commercial insurance (75.6%), Medicare (20.0%), and Medicaid (4.3%). Among patients who received treatment, most were female (85.9%) and middle-aged (median patient age, 55 years [range, 18–95 years]).

Medications Used by Patients

The most common medication claims in the first year after the diagnosis of SSc were for antibiotics, opioids, glucocorticoids, and proton pump inhibitors (Table 1). At the 1-year follow-up, among 2404 patients (30.8% of patients who received any treatment) who received IMTs, the median time from index date to first IMT was 66 days; 460 (19.1%) of these patients switched to a second type of IMT, and the median time to second IMT was 212 days.

SSc Manifestations

At the 1-year follow-up from SSc diagnosis, the most common organ manifestations identified in billing codes among 6852 patients with valid treatments of interest were lung (30.5%), heart (17.4%), and gastrointestinal tract (22.4%) (Table 2). The most common signs or symptoms reported by patients were musculoskeletal (16.1%) and fatigue (10.5%) symptoms. Infections were reported in 1035 patients (15.1%), malignancies in 14 patients (0.2%), and overlap syndrome in 956 patients (14.0%) (Table 2; Supplementary Appendix 2).

IMT Treatment Patterns During First Year of Follow-up from SSc Diagnosis

Among patients who received IMTs, 43.8% (1054/2404) were treated with at least hydroxychloroquine during the 1 year of follow-up from SSc diagnosis. The next most common IMTs received were MTX, MMF, azathioprine, and cyclosporine; these were used by 21.1%, 17.6%, 6.9%, and 6.5% of patients, respectively (Table 3). Lung, heart, gastrointestinal, and skin manifestations were most commonly reported in patients who received hydroxychloroquine, MTX, and MMF (Fig. 2; Supplementary Fig. S1). Most comorbidities reported during the first IMT treatment among the 2404 patients who received IMTs involved lung (11.8%), overlap syndrome (8.4%), heart (5.3%), and gastrointestinal system (6.8%) (Table 4). Among 2404 patients with SSc who started an IMT in their first year following diagnosis, 460 switched to a second IMT by the end of the first year of follow-up from the SSc diagnosis index; 23.0% of the switches were to treatments with at least MTX and 22.8% of the switches were to treatments with at least MMF (Table 3).

Use of Orally Administered Glucocorticoids

A total of 2345 patients were treated orally with daily glucocorticoids during the first year from index date; 802 (34.2%) received doses greater than 0 to 10 mg/day, 778 (33.2%) received doses greater than 10 to 20 mg/day, 538 (22.9%) received doses greater than 20 to 40 mg/day, 138 (5.9%) received doses greater than 40 to 60 mg/day, and 89 (3.8%) received doses greater than 60 mg/day.

Discussion

SSc presents unique challenges in managing a chronic multisystem autoimmune disease because it is a complex disease with devastating manifestations, and treatment is suboptimal [23]. The clinical heterogeneity of SSc determines variations in the degree of disease expression and prognosis, and, as a result, patients may experience a highly variable treatment course [24]. Treatment of SSc is limited to managing specific organ manifestations [24], but heterogeneity in the type of organ involvement presents challenges [25].

There are no approved agents that modify the disease course in SSc, but there are recommendations to support treatment and management of specific organ manifestations based on varying levels of evidence. EULAR and the EULAR Scleroderma Trials and Research, or EUSTAR group, have published evidence-based and consensus-derived recommendations for the treatment of SSc that may be used to guide treatment decisions in clinical practice, and these recommendations may be useful for providing direction for future research [15, 26]. The Scleroderma Clinical Trials Consortium and the Canadian Scleroderma Research group have also published consensus-derived management recommendations [22]. Although recommendations for the treatment of SSc are available, relatively little is known about how patients are actually treated in a real-world setting. A database analysis of investigations and medication use for SSc complications demonstrated that, in Canada, only 25–40% of patients received guideline-recommended treatment [27]. The present study is the first, to our knowledge, to investigate treatment patterns in patients with SSc, including types of treatment and disease manifestations, using real-world healthcare claims data. The results give insight into how patients with SSc are treated in the USA.

This retrospective cohort analysis of claims from a US healthcare insurance database revealed that among 6852 patients with SSc identified using a claims-based definition, the most common treatments received during the first year after diagnosis were antibiotics, opioids, systemic glucocorticoids, and proton pump inhibitors, whereas only 23% were treated with IMTs other than biologics. Approximately 47% of patients received glucocorticoids orally in the first year after the index date, most of them at doses less than 40 mg/day; however, 6% received glucocorticoids orally at a dose between 40 and 60 mg/day, and 4% received them at a dose of more than 60 mg/day. This might have been due to overlap with other rheumatic diseases such as systemic lupus erythematous (SLE) and rheumatoid arthritis, which are treated with higher doses of glucocorticoids than SSc. Only one-third of patients treated for SSc had IMT treatment during the first year after diagnosis. This may indicate that most patients in the present study had only mild disease without organ manifestations that needed treatment, or it may be a reflection of the limited efficacy of treatment options.

The most common organ manifestations in this claims database analysis involved the lung, heart, gastrointestinal tract, and skin, and infection was the most commonly reported complication. Although one-third of patients received IMTs during the first year after SSc diagnosis, the characterization of disease manifestations was similar between patients receiving IMTs and the overall SSc healthcare claims population, suggesting that patients who received IMTs did not have any particularly unique organ manifestations compared with patients with SSc in general or that IMTs are not considered beneficial for a particular organ manifestation. Therefore, this analysis could not distinguish a difference in disease manifestations between patients with SSc who received an immunosuppressant in the first year after diagnosis and patients who did not. Most medication claims in the first year after diagnosis of SSc were for glucocorticoids, opioids, antibiotics, and proton pump inhibitors. Of the patients who received IMTs and had musculoskeletal, gastrointestinal, heart, lung, or overlap syndrome manifestations, the most commonly received treatment was hydroxychloroquine sulfate, MTX, or MMF.

Limitations of the analysis include challenges that are inherent to claims-based data, such as a relatively short period of follow-up, lack of clinical data, inability to evaluate disease severity and activity, and the inability to differentiate between treatments received for SSc and those received for comorbidities. Although antibiotics were the most common treatment received, it was unclear, because of the claims nature of the study, whether they were prescribed to treat infection or bacterial overgrowth. It is known that patients with SSc can have overlap with other diseases, as shown in a recent study reporting a prevalence of 6.8% for overlap with SLE [28], and some patients in this analysis could have had mixed connective tissue disease without a full SSc diagnosis whereas others could have had true overlap syndrome. This could explain hydroxychloroquine being the most commonly initiated IMT among patients with SSc manifestations. It is also possible that the data could have captured nonspecific SSc manifestations or symptoms masked by codes for general arthritis. It should be noted that the results of the Scleroderma Lung Study II randomized controlled trial showing similarity between MMF and cyclophosphamide for the treatment of patients with SSc-related ILD [19] were not available before the cutoff date for this analysis and that current treatment guidelines were developed before the full results of the Scleroderma Lung Study II study were available [15]. Therefore, patterns of use of MMF must be investigated more closely using a more recent data set. Additional studies of the patterns of use of treatments for SSc will be valuable if new treatments become available. BSR/BHPR guidelines suggest that rituximab be considered for patients with SSc with skin involvement, although the evidence is weak [14]. Rituximab has been shown to improve skin sclerosis [29] and may have a beneficial effect on lung function [30] based on data from small open-label studies, but larger randomized controlled trials are lacking. More recently, the anti-interleukin-6 receptor-alpha (IL-6Rα) monoclonal antibody tocilizumab showed clinically relevant, although not statistically significant, improvement in lung function and no statistically significant change in skin sclerosis in phase 2 and phase 3 randomized controlled trials [31, 32]. Nintedanib slowed the rate of decline in pulmonary function in patients with SSc-ILD [33], and was recently approved for the treatment of SSc-ILD in the USA. On confirmation of the diagnosis, SSc is designated as either the limited cutaneous or the diffuse cutaneous subset based on the extent of skin thickening [14]. Different risks for organ complications in patients with SSc are associated with the limited cutaneous and diffuse cutaneous subtypes and their unique features [24]. However, a limitation of the current analysis is that these subtypes are not captured in claims data because they both fall under the same ICD-9 diagnosis for SSc. A more detailed disease diagnosis code, such as the ICD-10 update, could inform further on differences between patients with SSc who start an immunosuppressant in the first year after diagnosis and patients with SSc who do not.

Conclusion

The present study provides a snapshot of treatment patterns for SSc in the USA, but it is a rapidly changing landscape, and treatment patterns should continue to be investigated as new therapies are developed with the potential to enter the SSc treatment arena. SSc is a heterogeneous disease with complicated treatment patterns, and clinical trials informed by observational studies are still needed to find effective, disease-modifying treatments.

References

Nikpour M, Stevens WM, Herrick AL, Proudman SM. Epidemiology of systemic sclerosis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2010;24:857–69.

Ioannidis JP, Vlachoyiannopoulos PG, Haidich AB, et al. Mortality in systemic sclerosis: an international meta-analysis of individual patient data. Am J Med. 2005;118:2–10.

Mayes MD, Lacey JV Jr, Beebe-Dimmer J, et al. Prevalence, incidence, survival, and disease characteristics of systemic sclerosis in a large US population. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:2246–55.

Mayes MD. Scleroderma epidemiology. Rheum Dis Clin N Am. 2003;29:239–54.

Furst DE, Fernandes AW, Iorga SR, Greth W, Bancroft T. Epidemiology of systemic sclerosis in a large US managed care population. J Rheumatol. 2012;39:784–6.

Arias-Nunez MC, Llorca J, Vazquez-Rodriguez TR, et al. Systemic sclerosis in northwestern Spain: a 19-year epidemiologic study. Medicine. 2008;87:272–80.

Roberts-Thomson PJ, Jones M, Hakendorf P, et al. Scleroderma in South Australia: epidemiological observations of possible pathogenic significance. Intern Med J. 2001;31:220–9.

Silman A, Jannini S, Symmons D, Bacon P. An epidemiological study of scleroderma in the West Midlands. Br J Rheumatol. 1988;27:286–90.

Geirsson AJ, Steinsson K, Guthmundsson S, Sigurthsson V. Systemic sclerosis in Iceland. A nationwide epidemiological study. Ann Rheum Dis. 1994;53:502–5.

Andreasson K, Saxne T, Bergknut C, Hesselstrand R, Englund M. Prevalence and incidence of systemic sclerosis in southern Sweden: population-based data with case ascertainment using the 1980 ARA criteria and the proposed ACR-EULAR classification criteria. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:1788–92.

Hoffmann-Vold AM, Midtvedt O, Molberg O, Garen T, Gran JT. Prevalence of systemic sclerosis in south-east Norway. Rheumatology. 2012;51:1600–5.

Chifflot H, Fautrel B, Sordet C, Chatelus E, Sibilia J. Incidence and prevalence of systemic sclerosis: a systematic literature review. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2008;37:223–35.

Khanna D, Distler JHW, Sandner P, Distler O. Emerging strategies for treatment of systemic sclerosis. J Scleroderma Relat Disord. 2016;1:186–93.

Denton CP, Hughes M, Gak N, et al. BSR and BHPR guideline for the treatment of systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology. 2016;55:1906–10.

Kowal-Bielecka O, Fransen J, Avouac J, et al. Update of EULAR recommendations for the treatment of systemic sclerosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:1327–39.

Pope JE, Bellamy N, Seibold JR, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of methotrexate versus placebo in early diffuse scleroderma. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:1351–8.

Tashkin DP, Elashoff R, Clements PJ, et al. Cyclophosphamide versus placebo in scleroderma lung disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2655–66.

Hoyles RK, Ellis RW, Wellsbury J, et al. A multicenter, prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of corticosteroids and intravenous cyclophosphamide followed by oral azathioprine for the treatment of pulmonary fibrosis in scleroderma. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:3962–70.

Tashkin DP, Roth MD, Clements PJ, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil versus oral cyclophosphamide in scleroderma-related interstitial lung disease (SLS II): a randomised controlled, double-blind, parallel group trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2016;4:708–19.

Burt RK, Shah SJ, Dill K, et al. Autologous non-myeloablative haemopoietic stem-cell transplantation compared with pulse cyclophosphamide once per month for systemic sclerosis (ASSIST): an open-label, randomised phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2011;378:498–506.

van Laar JM, Farge D, Sont JK, et al. Autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation vs intravenous pulse cyclophosphamide in diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;311:2490–8.

Walker KM, Pope J. Treatment of systemic sclerosis complications: what to use when first-line treatment fails–a consensus of systemic sclerosis experts. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2012;42:42–55.

Sakkas LI. Spotlight on tocilizumab and its potential in the treatment of systemic sclerosis. Drug Des Dev Ther. 2016;10:2723–8.

Shah AA, Wigley FM. My approach to the treatment of scleroderma. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88:377–93.

Nihtyanova SI, Ong VH, Denton CP. Current management strategies for systemic sclerosis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2014;32:156–64.

Kowal-Bielecka O, Landewe R, Avouac J, et al. EULAR recommendations for the treatment of systemic sclerosis: a report from the EULAR Scleroderma Trials and Research group (EUSTAR). Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:620–8.

Pope J, Harding S, Khimdas S, Bonner A, Baron M. Agreement with guidelines from a large database for management of systemic sclerosis: results from the Canadian Scleroderma Research Group. J Rheumatol. 2012;39:524–31.

Alharbi S, Ahmad Z, Bookman AA, et al. Epidemiology and survival of systemic sclerosis-systemic lupus erythematosus overlap syndrome. J Rheumatol. 2018;45:1406–10.

Bosello S, De Santis M, Lama G, et al. B cell depletion in diffuse progressive systemic sclerosis: safety, skin score modification and IL-6 modulation in an up to thirty-six months follow-up open-label trial. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12:R54.

Daoussis D, Melissaropoulos K, Sakellaropoulos G, et al. A multicenter, open-label, comparative study of B-cell depletion therapy with rituximab for systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2017;46:625–31.

Khanna D, Denton CP, Jahreis A, et al. Safety and efficacy of subcutaneous tocilizumab in adults with systemic sclerosis (faSScinate): a phase 2, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;387:2630–40.

Khanna D, Lin CJF, Kuwana M, et al. Efficacy and safety of tocilizuamb for the treatment of systemic sclerosis; results from a phase 3 randomized controlled trial [abstract]. Arthritis Rheum. 2018;70(suppl 10). https://acrabstracts.org/abstract/efficacy-and-safety-of-tocilizumab-for-the-treatment-of-systemic-sclerosis-results-from-a-phase-3-randomized-controlled-trial/. Accessed Sept 2, 2019.

Distler O, Highland KB, Gahlemann M, et al. Nintedanib for systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:2518–28.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This study and the journal’s Rapid Service Fee were funded by F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd.

Medical Writing Assistance

The authors thank Liselle Bovell, PhD, and Sara Duggan, PhD, of ApotheCom who provided writing services on behalf of F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

Sara L. Gale is an employee of Genentech and owns stock in F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd. Huong Trinh is an employee of Genentech and owns stock in F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd. Celia J. F. Lin is an employee of Genentech and owns stock in F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd. Khaled Sarsour is an employee of Genentech and owns stock in F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd. Nitya Mathew is a former employee of Genentech and is now employed by Workforce Junction, Concord, CA, USA. Angelika Jahreis is a former employee of Genentech and is now employed by Gilead Sciences, Foster City, CA, USA.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This study only used de-identified patient data from a database; therefore, ethics committee approval and informed consent were not needed.

Data Availability

Deidentified patient data, protocols, and statistical analysis plans are available upon reasonable request via www.clinicalstudydatarequest.com.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced Digital Features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.10011572.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Gale, S.L., Trinh, H., Mathew, N. et al. Characterizing Disease Manifestations and Treatment Patterns Among Adults with Systemic Sclerosis: A Retrospective Analysis of a US Healthcare Claims Population. Rheumatol Ther 7, 89–99 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40744-019-00181-8

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40744-019-00181-8