Abstract

Background

Urban racial arrest disparities are well known. Emerging evidence suggests that rural policing shares similar patterns as urban policing in the USA, but without receiving the same public scrutiny, raising the risk of biased rural policing going unnoticed.

Methods

We estimated adult and adolescent arrest rates and rate ratios (RR) by race, rural-urban status, and US region based on 2016 Uniform Crime Reporting Program arrest and US Census population counts using general estimating equation Poisson regression models with a 4-way interaction between race, region, age group, and urbanicity.

Results

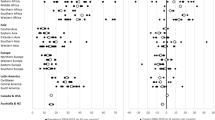

With few exceptions, arrest rates were highest in small towns and rural areas, especially among Black and American Indian populations. Arrest rates differed between US regions with highest rates and racial disparities in the Midwest. For example, arrest rates among Black adults in the rural Midwest were 148.6 arrests [per 1000 population], 95% CI 131.4–168.0, versus 94.4 arrests, 95% CI 77.2–115.4 in the urban Midwest; and versus corresponding rural Midwest arrests among white adults, 32.7 arrests, 95% CI 30.8–34.8, Black versus white rural RR 4.54, 95% CI 4.09–5.04. Racial arrest disparities in the South were lower but still high, e.g., rural South, Black versus White adults, RR 1.86, 95% CI 1.71–2.03.

Conclusions

Rural areas and small towns are potential hotspots of racial arrest disparities across the USA, especially in the Midwest. Approaches to overcoming structural racism in policing must include strategies targeted at rural/small town communities. Our findings underscore the importance of dismantling racist policing in all US communities.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

NAACP. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Criminal Justice Fact Sheet; 2021. https://naacp.org/resources/criminal-justice-fact-sheet. Accessed 3 Feb 2022.

University of Minnesota. Center for Antiracism. Shared Terms. https://carhe.umn.edu/our-work/shared-terms. Accessed 16 Nov 2022.

Western B. Punishment and inequality in America. Russell Sage Foundation; 2006.

Eason JM. Big house on the prairie: rise of the rural ghetto and prison proliferation. University of Chicago Press; 2019.

Alang S, McAlpine D, McCreedy E, Hardeman R. Police brutality and black health: setting the agenda for public health scholars. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(5):662–5.

Gilmore RW. Abolition geography: essays towards liberation. Verso Books; 2022.

Radebe P. Derek Chauvin: Racist cop or product of a racist police academy? J Black Stud. 2021;52(3):231–47.

Rosino ML, Hughey MW. The war on drugs, racial meanings, and structural racism: a holistic and reproductive approach. Am J Econ Sociol. 2018;77(3-4):849–92.

Bass S. Policing space, policing race: social control imperatives and police discretionary decisions. Social justice. 2001;28(83):156–76.

Heard-Garris N, Johnson TJ, Hardeman R. The harmful effects of policing—from the neighborhood to the hospital. JAMA Pediatr. 2022;176(1):23–5.

Jindal M, Mistry KB, Trent M, McRae A, Thornton RL. Police exposures and the health and well-being of Black youth in the US: a systematic review. JAMA Pediatr. 2022;176(1):78–88.

Hardeman RR, Chantarat T, Smith ML, Van Riper DC, Mendez DD. Association of residence in high–police contact neighborhoods with preterm birth among Black and White individuals in Minneapolis. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(12):e2130290-e.

Krieger N. Discrimination and health inequities. Int J Health Serv. 2014;44(4):643–710.

Williams DR, Lawrence JA, Davis BA, Vu C. Understanding how discrimination can affect health. Health Serv Res. 2019;54:1374–88.

Hahn RA, Truman BI, Williams DR. Civil rights as determinants of public health and racial and ethnic health equity: health care, education, employment, and housing in the United States. SSM-Population Health. 2018;4:17–24.

Brunson RK, Wade BA. “Oh hell no, we don’t talk to police” Insights on the lack of cooperation in police investigations of urban gun violence. Criminol Public Policy. 2019;18(3):623–48.

McFarland MJ, Geller A, McFarland C. Police contact and health among urban adolescents: the role of perceived injustice. Soc Sci Med. 2019;238:112487.

Frey WH. Mapping Americas diversity with the 2020 census. 2022.

US Census. Racial and Ethnic Diversity in the United States: 2010 Census and 2020 Census. https://www.census.gov/library/visualizations/interactive/racial-and-ethnic-diversity-in-the-united-states-2010-and-2020-census.html. Accessed 7 Apr 2022.

US Census. Rural America. https://mtgis-portal.geo.census.gov/arcgis/apps/MapSeries/index.html?appid=49cd4bc9c8eb444ab51218c1d5001ef6. Accessed 7 Apr 2022.

Paulsen KE. Making character concrete: empirical strategies for studying place distinction. City Community. 2004;3(3):243–62.

McHenry-Sorber E. The power of competing narratives: a new interpretation of rural school-community relations. Peabody J Educ. 2014;89(5):580–92.

Dorfman LT, Murty SA, Evans RJ, Ingram JG, Power JR. History and identity in the narratives of rural elders. J Aging Stud. 2004;18(2):187–203.

Leverentz A. Narratives of crime and criminals: how places socially construct the crime problem 1. In Sociological forum (Vol. 27, No. 2, pp. 348–371). Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2012.

Taylor E, Guy-Walls P, Wilkerson P, Addae R. The historical perspectives of stereotypes on African-American males. J Hum Rights Soc Work. 2019;4(3):213–25.

Simes JT. Place and punishment: the spatial context of mass incarceration. J Quant Criminol. 2018;34:513–33.

Simes JT, Beck B, Eason JM. Policing, Punishment, and place: spatial-contextual analyses of the criminal legal system. Annu Rev Sociol. 2023;49.

Beck B. Broken windows in the cul-de-sac? Race/ethnicity and quality-of-life policing in the changing suburbs. Crime Delinq. 2019;65(2):270–92.

Kang-Brown J, Subramanian R. Out of sight: the growth of jails in rural America. New York, NY: Vera Institute of Justice; 2017.

Beckett K, Beach L. The place of punishment in twenty-first-century America: understanding the persistence of mass incarceration. Law Soc Inq. 2021;46(1):1–31.

Simes JT. Punishing places: the geography of mass imprisonment. Univ of California Press; 2021.

The Marshall Project. Alysia Santo and R.G. Dunlop. Shooting first and asking questions later. 2021. https://www.themarshallproject.org/2021/08/13/shooting-first-and-asking-questions-later. Accessed 17 Nov 2022.

Collaborators GPVUS. Fatal police violence by race and state in the USA, 1980–2019: a network meta-regression. The Lancet. 2021;398(10307):1239–55.

The ‘demure white supremacy of the Midwest’. 2021. https://littlevillagemag.com/the-demure-white-supremacy-of-the-midwest/. Accessed 7 Apr 2022.

Gordon C. Race in the Heartland. Washington, DC: Economic Policy Institute; 2019.

Maldonado MM. Latino incorporation and racialized border politics in the heartland: interior enforcement and policeability in an English-only state. Am Behav Sci. 2014;58(14):1927–45.

National Archive of Criminal Justice Data. Uniform crime reporting program data series. Federal Bureau of Investigation; 2016. https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/web/NACJD/series/00057. Accessed 17 Nov 2022.

Kaplan J. Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) program data: arrests by age, sex, and race, 1974-2016. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor], 2018-12-29. https://doi.org/10.3886/E102263V7. https://www.openicpsr.org/openicpsr/project/102263/version/V7/view. Accessed 17 Nov 2022.

United States Census Bureau. Annual county resident population estimates by age, sex, race, and Hispanic origin, 2019. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/popest/2010s-counties-detail.html. Accessed 21 Dec 2022.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Health Statistics. Urban-Rural Classification Scheme for Counties.2013 https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data_access/urban_rural.htm. Accessed 17 Nov 2022.

United States Census Bureau Data. https://www.census.gov/data.html. Accessed 21 Dec 2022.

Johfre SS, Freese J. Reconsidering the reference category. Sociol Methodol. 2021;51(2):253–69.

SAS Version 9.4. SAS Institute Inc., Cary.

Muentner L, Heard-Garris N, Shlafer R. Parental incarceration among youth. Pediatrics. 2022;150(6):e2022056703.

Zahnd WE, Murphy C, Knoll M, Benavidez GA, Day KR, Ranganathan R, et al. The intersection of rural residence and minority race/ethnicity in cancer disparities in the United States. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(4):1384.

Murphey D, Cooper PM Child Trends. Parents behind bars: what happens to their children? https://www.childtrends.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/2015-42ParentsBehindBars.pdf. Accessed 8 Feb 2023.

Cate SD. The Mississippi model: dangers of prison reform in the context of fiscal austerity. Punishment Soc. 2022;24(4):715–41.

Henning-Smith C, Moscovice I, Kozhimannil K. Differences in social isolation and its relationship to health by rurality. J Rural Health. 2019;35(4):540–9.

Cikara M, Fouka V, Tabellini M. Hate crime towards minoritized groups increases as they increase in sized-based rank. Nat Hum Behav. 2022;6(11):1537–44.

Jacobs D, Carmichael JT, Kent SL. Vigilantism, current racial threat, and death sentences. Am Sociol Rev. 2005;70(4):656–77.

Wilkerson I. The warmth of other suns: The epic story of America’s great migration. Penguin UK; 2020.

Sugrue TJ. The origins of the urban crisis: Race and inequality in postwar detroit-updated edition (Vol. 168). Princeton University Press; 2014.

The Prison Policy Initiative. Prison Gerrymandering Project. https://www.prisonersofthecensus.org/impact.html. Accessed 19 Apr 2023.

Braga AA, Brunson RK, Drakulich KM. Race, place, and effective policing. Annu Rev Sociol. 2019;45(1):535–55.

NORC at the University of Chicago. Improving data infrastructure to reduce firearms violence. Final Report. 2021. p. 67–72 https://www.norc.org/PDFs/A%20Blueprint%20for%20U.S.%20Firearms%20Data%20Infrastructure/Improving%20Data%20Infrastructure%20to%20Reduce%20Firearms%20Violence_Final%20Report.pdf.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Jacob Kaplan, PI on the Open ICPSR UCR project, for his helpful input on the UCR arrest data.

Funding

There was no external funding specifically for this study. Carrie Henning-Smith was supported by the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, grant UL1TR002494.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Patricia I. Jewett: initial study idea; conception and design; download and analysis of data; interpretation and contextualization of the results; article draft and revision; final approval of the manuscript. Ronald E. Gangnon: statistical method supervision; analysis of data and validation; interpretation of the results; article review and revision; final approval of the manuscript. Anna K. Hing, Carrie Henning-Smith, Tongtan Chantarat, and Eunice M. Areba: conception and design; interpretation and contextualization of the results; article review and revision; final approval of the manuscript. Iris W. Borowsky: supervision; conception and design; interpretation and contextualization of the results; article review and revision; final approval of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix A

Hypothetical example calculation of group-specific population weights based on the number of months with reported data in each agency

Region | State | County | Agency | Number of months reported | Inflation factor | Group: adult White | Group: adult Black | Group: juvenile White | Group: juvenile Black | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Actual arrest counts | Inflated arrest counts | Actual arrest counts | Inflated arrest counts | Actual arrest counts | Inflated arrest counts | Actual arrest counts | Inflated arrest counts | ||||||

1 | 2 | 3 | A | 12 | 1 (= 12/12) | 100 | 100 (= 100*1) | 60 | 60 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

B | 6 | 2 (= 12/6) | 50 | 100 (= 50*2) | 40 | 80 | 10 | 20 | 7 | 14 | |||

C | 7 | 1.714 (= 12/7) | 58 | 99.429 (= 58*1.714) | 50 | 85.714 | 11 | 18.857 | 22 | 37.714 | |||

D | 9 | 1.333 (= 12/9) | 75 | 100 (= 75*1.333) | 50 | 66.667 | 13 | 17.333 | 10 | 13.333 | |||

E | 1 | 12 (= 12/1) | 8 | 96 (= 8*12) | 5 | 60 | 2 | 24 | 6 | 72 | |||

Actual arrest sum in county | 291 | 205 | 56 | 65 | |||||||||

Inflated arrest sum in county | 495.429 | 352.381 | 100.190 | 157.048 | |||||||||

County population weight | 0.587 (= 291/495.429) | 0.582 | 0.559 | 0.414 | |||||||||

Appendix B

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Jewett, P.I., Gangnon, R.E., Hing, A.K. et al. Racial Arrest Disparities in the USA by Rural-Urban Location and Region. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-023-01703-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-023-01703-5