Abstract

Background

Qualitative research during the development/testing of Patient Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) is recommended to support content validity. However, it is unclear if and how young children (≤ 7 years) can be involved in this research because of their unique cognitive needs.

Objectives

Here we investigate the involvement of children (≤ 7 years) in qualitative research for PROM development/testing. This review aimed to identify (1) which stages of qualitative PROM development children ≤ 7 years had been involved in, (2) which subjective health concepts had been explored within qualitative PROM development with this age group, and (3) which qualitative methods had been reported and how these compared with existing methodological recommendations.

Methods

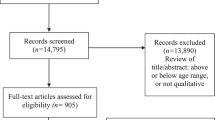

This scoping review systematically searched three electronic databases (searches re-run prior to final analysis on 29 June 2022) with no date restrictions. Included studies had samples of at least 75% aged ≤ 7 years or reported distinct qualitative methods for children ≤ 7 years in primary qualitative research to support concept elicitation or PROM development/testing. Articles not in English and PROMs that did not enable children ≤ 7 years to self-report were excluded. Data on study type, subjective health and qualitative methods were extracted and synthesised descriptively. Methods were compared with recommendations from guidance.

Results

Of 19 included studies, 15 reported concept elicitation research and 4 reported cognitive interviewing. Most explored quality of life (QoL)/health-related quality of life (HRQoL). Some concept elicitation studies reported that creative/participatory activities had supported children’s engagement, but results and reporting detail varied considerably across studies. Cognitive interviewing studies reported less methodological detail and fewer methods adapted for young children compared with concept elicitation studies. They were limited in scope regarding assessments of content validity, mostly focussing on clarity while relevance and comprehensiveness were explored less.

Discussion

Creative/participatory activities may be beneficial in concept elicitation research with children ≤ 7 years, but future research needs to explore what contributes to the success of young children’s involvement and how researchers can adopt flexible methods. Cognitive interviews with young children are limited in frequency, scope and reported methodological detail, potentially impacting PROM content validity for this age group. Without detailed reporting, it is not possible to determine the feasibility and usefulness of children’s (≤ 7 years) involvement in qualitative research to support PROM development and assessment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

A scoping review aims to systematically identify the breadth of evidence on a particular topic and to describe the characteristics of that evidence [58, 60]. Given this area of research is relatively unknown, especially within the specific age range of ≤ 7 years, a scoping review methodology was considered appropriate.

References

Cremeens J, Eiser C, Blades M. Characteristics of health-related self-report measures for children aged three to eight years: a review of the literature. Qual Life Res. 2006. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-005-4184-x.

Germain N, Aballéa S, Toumi M. Measuring health-related quality of life in young children: how far have we come? J Market Access Health Policy. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1080/20016689.2019.1618661.

Matza LS, et al. Pediatric patient-reported outcome instruments for research to support medical product labeling: report of the ISPOR PRO good research practices for the assessment of children and adolescents task force. Value Health. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2013.04.004.

Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry-Patient-reported Outcome Measures: Use in Medical Product Development to Support Labeling Claims. Silver Spring, MD: Food and Drug Administration, 2009.

European Medicines Agency. Reflection Paper on the Regulatory Guidance for the Use of Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQL) Measures in the Evaluation of Medicinal Products. London, United Kingdom: European Medicines Agency. Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP), 2005.

Bevans K, et al. Patient reported outcomes as indicators of pediatric health care quality. Acad Pediatr. 2014;14(5):S90–6.

Brazier J, et al. Measuring and valuing health benefits for economic evaluation. 2nd ed. Oxford: University Press; 2017.

Karimi M, Brazier J. Health, health-related quality of life, and quality of life: what is the difference? Pharmacoeconomics. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-016-0389-9.

Black N. Patient reported outcome measures could help transform healthcare. BMJ. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f167.

Kwon J, et al. Systematic review of conceptual, age, measurement and valuation considerations for generic multidimensional childhood patient-reported outcome measures. Pharmacoeconomics. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-021-01128-0.

Janssens A, et al. A systematic review of generic multidimensional patient-reported outcome measures for children, part I: descriptive characteristics. Value Health. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2014.12.006.

Meryk A, et al. Implementation of daily patient-reported outcome measurements to support children with cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.29279.

Arbuckle R, Abetz-Webb L. “Not just little adults”: qualitative methods to support the development of pediatric patient-reported outcomes. Patient Patient Center Outcomes Res. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-013-0022-3.

Patrick D, et al. Content validity—establishing and reporting the evidence in newly developed patient-reported outcomes (PRO) instruments for medical product evaluation: ISPOR PRO Good Research Practices Task Force report: part 2—assessing respondent understanding. Value Health. 2011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2011.06.013.

Patrick D, et al. Content validity—establishing and reporting the evidence in newly developed patient-reported outcomes (PRO) instruments for medical product evaluation: ISPOR PRO good research practices task force report: part 1—eliciting concepts for a new PRO instrument. Value Health. 2011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2011.06.014.

Terwee CB, et al. COSMIN methodology for evaluating the content validity of patient-reported outcome measures: a Delphi study. Quality Life Res. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-1829-0.

Brod M, Tesler LE, Christensen TL. Qualitative research and content validity: developing best practices based on science and experience. Qual Life Res. 2009. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-009-9540-9.

Lasch K, et al. PRO development: rigorous qualitative research as the crucial foundation. Qual Life Res. 2010. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-010-9677-6.

Stevens K, Palfreyman S. The use of qualitative methods in developing the descriptive systems of preference-based measures of health-related quality of life for use in economic evaluation. Value Health. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2012.08.2204.

Willis GB. Cognitive interviewing: a tool for improving questionnaire design. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2005.

Terwee CB, et al. COSMIN methodology for assessing the content validity of PROMs–user manual. Amsterdam: VU University Medical Center; 2018.

Patel ZS, Jensen SE, Lai S. Considerations for conducting qualitative research with pediatric patients for the purpose of PRO development. Qual Life Res. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-016-1256-z.

Arsiwala T, et al. Measuring what matters for children: a systematic review of frequently used pediatric generic PRO instruments. Therap Innov Regul Sci. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43441-021-00311-x.

Husbands S, Mitchell PM, Coast J. A systematic review of the use and quality of qualitative methods in concept elicitation for measures with children and young people. Patient Patient Center Outcomes Res. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-020-00414-x.

Willis J, et al. Engaging the voices of children: a scoping review of how children and adolescents are involved in the development of quality-of-life–related measures. Value Health. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2020.11.007.

Rothmund M, et al. A critical evaluation of the content validity of patient-reported outcome measures assessing health-related quality of life in children with cancer: a systematic review. J Patient-Report Outcomes. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41687-023-00540-8.

Basic documents: forty-ninth edition (including amendments adopted up to 31 May 2019). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO

Page MJ, et al. The PRISMA statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71.

Hyslop S, et al. Identifying symptoms using the drawings of 4–7 year olds with cancer. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2018.08.004.

Tomlinson D, et al. Development of mini-SSPedi for children 4–7 years of age receiving cancer treatments. BMC Cancer. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-018-5210-z.

McHugh ML. Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem Med. 2012;22(3):276–82.

Carlton J. Identifying potential themes for the Child Amblyopia Treatment Questionnaire. Optom Vis Sci. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1097/OPX.0b013e318290cd7b.

Carlton J. Developing the draft descriptive system for the child amblyopia treatment questionnaire (CAT-Qol): a mixed methods study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-11-174.

Connor NP, et al. Attitudes of children with dysphonia. J Voice. 2008. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvoice.2006.09.005.

Zieschank KL, et al. Children’s perspectives on emotions informing a child-reported screening instrument. J Child Fam Stud. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-021-02086-z.

Coussens M, et al. A Qualitative Photo Elicitation Research Study to elicit the perception of young children with Developmental Disabilities such as ADHD and/or DCD and/or ASD on their participation. PLoS ONE. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0229538.

Christie D, et al. Exploring views on satisfaction with life in young children with chronic illness: an innovative approach to the collection of self-report data from children under 11. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104510392309.

Follansbee-Junger KW, et al. Development of the PedsQL (TM) Epilepsy Module: focus group and cognitive interviews. Epilep Behav. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2016.06.011.

Franciosi JP, et al. Quality of life in paediatric eosinophilic oesophagitis: what is important to patients? Child Care Health Dev. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2214.2011.01265.x.

Krenz U, et al. Health-related quality of life after pediatric traumatic brain injury: a qualitative comparison between children’s and parents’ perspectives. PLoS ONE. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0246514.

Nutakki K, et al. Development of the pediatric quality of life inventory neurofibromatosis type 1 module items for children, adolescents and young adults: qualitative methods. J Neuro-Oncol. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-016-2351-2.

Panepinto JA, Torres S, Varni JW. Development of the PedsQL TM Sickle Cell Disease Module items: qualitative methods. Qual Life Res. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-011-9941-4.

Varni JW, et al. PedsQL gastrointestinal symptoms module item development: qualitative methods. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPG.0b013e31823c9b88.

Wiener L, et al. Child and parent perspectives of the chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGVHD) symptom experience: a concept elicitation study. Support Care Cancer. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-013-1957-6.

Morris C, et al. Development of the Oxford ankle foot questionnaire: finding out how children are affected by foot and ankle problems. Child Care Health Dev. 2007. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2214.2007.00770.x.

Markham C, et al. Children with speech, language and communication needs their perceptions of their quality of life. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2009. https://doi.org/10.1080/13682820802359892.

Gao W, et al. Development and pilot testing a self-reported pediatric PROMIS App for young children aged 5–7 years. J Pediatr Nurs. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2020.04.003.

Hwang M, et al. Development of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory™ Spinal Cord Injury (PedsQL™ SCI) module: qualitative methods. Spinal Cord. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-020-0450-6.

Churruca K, et al. Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs): a review of generic and condition-specific measures and a discussion of trends and issues. Health Expect. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.13254.

Riley AW. Evidence that school-age children can self-report on their health. Ambul Pediatr. 2004. https://doi.org/10.1367/A03-178R.1.

Curtin C. Eliciting children’s voices in qualitative research. The Am J Occup Therap. 2001. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.55.3.295.

Kitto S, et al. Quality in qualitative research. Med J Aust. 2008;188:243.

Boeije H, Willis G. The cognitive interviewing reporting framework (CIRF). Methodology. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1027/1614-2241/a000075.

Wright J, Moghaddam N, Dawson DL. Cognitive interviewing in patient-reported outcome measures: a systematic review of methodological processes. Qualit Psychol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1037/qup0000145.

Bevans K, et al. Conceptual and methodological advances in child-reported outcomes measurement. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2010. https://doi.org/10.1586/erp.10.52.

Rebok G, et al. Elementary school-aged children’s reports of their health: a cognitive interviewing study. Qual Life Res. 2001. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1016693417166.

Drennan J. Cognitive interviewing: verbal data in the design and pretesting of questionnaires. J Adv Nurs. 2003. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02579.x.

Papaioannou D, Sutton A, Booth A. Systematic approaches to a successful literature review. 2nd ed. London: SAGE Publications; 2016.

Peters M, et al. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. JBI Evid Implement. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050.

Campbell F, et al. Mapping reviews, scoping reviews, and evidence and gap maps (EGMs): the same but different—the “Big Picture” review family. Systematic Rev. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-023-02178-5.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank John Brazier for his support conceptualising the review and methodology, and ongoing help throughout the review process. We would also like to thank Louise Falzon for her support developing the search strategies for online databases.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This review is part of PhD research funded by SF-6D royalty income.

Conflicts of interest

Victoria Gale and Jill Carlton declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Data availability statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available in Online Resource 4.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to study conception, design, and review preparation. Data extraction and analysis was performed by VG. VG prepared the first draft of the manuscript, and both authors commented on previous versions. The final version was read and approved by both authors.

Ethics approval and consent to participate and publication

Not applicable.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Gale, V., Carlton, J. Including Young Children in the Development and Testing of Patient Reported Outcome (PRO) Instruments: A Scoping Review of Children’s Involvement and Qualitative Methods. Patient 16, 425–456 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-023-00637-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-023-00637-8