Abstract

Background

Women with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) face difficult decisions regarding treatment during pregnancy: while the majority of IBD medications are safe, there is substantial societal pressure to avoid exposures during pregnancy. However, discontinuation of IBD medications risks a disease flare occurring during pregnancy.

Objective

This study quantified women’s knowledge about pregnancy and IBD and their willingness to accept the risks of adverse pregnancy outcomes to avoid disease activity or medication use during pregnancy.

Methods

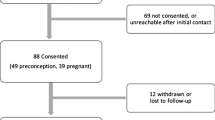

Women with IBD recruited from four centers completed an online discrete-choice experiment stated-preference study including eight choice tasks and the Crohn’s and Colitis Pregnancy Knowledge questionnaire. Random-parameters logit was used to estimate preferences for both the respondent personally and what the respondent thought most women would prefer. We also tested for systematically different preferences among individuals with different demographic and personal characteristics, including IBD knowledge. The primary outcome was the maximum acceptable risk of premature birth, birth defects, or miscarriage that women with IBD were willing to accept to avoid (1) taking an IBD medication or (2) having a disease flare during pregnancy.

Results

Among 230 respondents, women would accept, on average, up to a 4.9% chance of miscarriage to avoid a disease flare. On average, there were no statistically significant differences in women’s preferences for continuing versus avoiding medication in the absence of a flare. However, prior understanding of IBD and pregnancy significantly affected preferences for IBD medication use during pregnancy: women with “poor knowledge” would accept up to a 6.4% chance of miscarriage to avoid IBD medication use during pregnancy, whereas women with “adequate knowledge” would accept up to a 5.1% chance of miscarriage in order to remain on their medication. Respondents’ personal treatment preferences did not differ from their assessment of other women’s preferences.

Conclusions

Women with IBD demonstrated a strong preference for avoiding disease activity during pregnancy. Knowledge regarding pregnancy and IBD was a strong modifier of preferences for continuation of IBD medications during pregnancy. These findings point to an important opportunity for intervention to improve disease control through education to increase medication adherence and alleviate unnecessary fears about IBD medication use during pregnancy.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Dahlhamer JM, Zammitti EP, Ward BW, et al. Prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease among adults aged >/=18 years-United States, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:1166–9.

Sairenji T, Collins KL, Evans DV. An update on inflammatory bowel disease. Prim Care. 2017;44:673–92.

Willoughby CP, Truelove SC. Ulcerative colitis and pregnancy. Gut. 1980;21:469–74.

Khosla R, Willoughby CP, Jewell DP. Crohn’s disease and pregnancy. Gut. 1984;25:52–6.

de Lima-Karagiannis A, Zelinkova-Detkova Z, van der Woude CJ. The effects of active IBD during pregnancy in the era of novel IBD therapies. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:1305–12.

Zelinkova Z, van der Ent C, Bruin KF, et al. Effects of discontinuing anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy during pregnancy on the course of inflammatory bowel disease and neonatal exposure. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:318–21.

Luu M, Benzenine E, Doret M, et al. Continuous anti-TNFalpha use throughout pregnancy: possible complications for the mother but not for the fetus. A retrospective cohort on the French National Health Insurance Database (EVASION). Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113:1669–77.

Mozaffari S, Abdolghaffari AH, Nikfar S, et al. Pregnancy outcomes in women with inflammatory bowel disease following exposure to thiopurines and antitumor necrosis factor drugs: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2015;34:445–59.

Mahadevan U, Kane S. American gastroenterological association institute technical review on the use of gastrointestinal medications in pregnancy. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:283–311.

Mahadevan U, Robinson C, Bernasko N, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease in pregnancy clinical care pathway: a report from the american gastroenterological association IBD Parenthood Project Working Group. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019;25:627–41.

Akbari M, Shah S, Velayos FS, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis on the effects of thiopurines on birth outcomes from female and male patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:15–22.

Mahadevan U, Long MD, Kane SV, et al. Pregnancy and neonatal outcomes after fetal exposure to biologics and thiopurines among women with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:1131–9.

Wolgast E, Lindh-Astrand L, Lilliecreutz C. Women’s perceptions of medication use during pregnancy and breastfeeding—a Swedish cross-sectional questionnaire study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2019;98:856–64.

Mountifield RE, Prosser R, Bampton P, et al. Pregnancy and IBD treatment: this challenging interplay from a patients’ perspective. J Crohns Colitis. 2010;4:176–82.

Bewtra M, Fairchild AO, Gilroy E, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease patients’ willingness to accept medication risk to avoid future disease relapse. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:1675–81.

Bewtra M, Kilambi V, Fairchild AO, et al. Patient preferences for surgical versus medical therapy for ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:103–14.

Selinger CP, Eaden J, Selby W, et al. Patients’ knowledge of pregnancy-related issues in inflammatory bowel disease and validation of a novel assessment tool ('CCPKnow’). Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;36:57–63.

Bridges JF, Hauber AB, Marshall D, et al. Conjoint analysis applications in health—a checklist: a report of the ISPOR Good Research Practices for Conjoint Analysis Task Force. Value Health. 2011;14:403–13.

Gallinger ZR, Rumman A, Nguyen GC. Perceptions and attitudes towards medication adherence during pregnancy in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10:892–7.

Moscandrew M, Kane S. Inflammatory bowel diseases and management considerations: fertility and pregnancy. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2009;11:395–9.

Visschers VH, Meertens RM, Passchier WW, et al. Probability information in risk communication: a review of the research literature. Risk Anal. 2009;29:267–87.

Kanninen BJ. Optimal design for multinomial choice experiments. J Mark Res. 2002;39:214–27.

Kuhfeld WF. Experimental design: efficiency, coding, and choice designs. MR-2010C. 2010.

Kuhfeld WF. Marketing research methods in SAS. MR-2010. 2010.

Huber J, Zwerina K. The Importance of utility Balance and Efficient Choice Designs. J Mark Res. 1996;33:307–17.

Dey A. Orthogonal fractional factorial designs 133. Wiley; 1985.

Dillman DA, Smyth JD. Design effects in the transition to web-based surveys. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32:S90–6.

Johnson FR, Yang JC, Reed SD. The internal validity of discrete choice experiment data: a testing tool for quantitative assessments. Value Health. 2019;22:157–60.

Janssen EM, Marshall DA, Hauber AB, et al. Improving the quality of discrete-choice experiments in health: how can we assess validity and reliability? Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2017;17:531–42.

Tervonen T, Schmidt-Ott T, Marsh K, et al. Assessing rationality in discrete choice experiments in health: an investigation into the use of dominance tests. Value Health. 2018;21:1192–7.

Bortlik M, Duricova D, Machkova N, et al. Discontinuation of anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy in inflammatory bowel disease patients: a prospective observation. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2016;51:196–202.

Cao RH, Grimm MC. Pregnancy and medications in inflammatory bowel disease. Obstet Med. 2021;14:4–11.

https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/pretermbirth.htm. Accessed 13 Aug 2021.

McConnell RA, Mahadevan U. Pregnancy and the patient with inflammatory bowel disease: fertility, treatment, delivery, and complications. Gastroenterol Clin N Am. 2016;45:285–301.

Stephansson O, Larsson H, Pedersen L, et al. Congenital abnormalities and other birth outcomes in children born to women with ulcerative colitis in Denmark and Sweden. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:795–801.

O’Toole A, Nwanne O, Tomlinson T. Inflammatory bowel disease increases risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes: a meta-analysis. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60:2750–61.

Broms G, Granath F, Linder M, et al. Birth outcomes in women with inflammatory bowel disease: effects of disease activity and drug exposure. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:1091–8.

Schnitzler F, Fidder H, Ferrante M, et al. Outcome of pregnancy in women with inflammatory bowel disease treated with antitumor necrosis factor therapy. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:1846–54.

Katz JA, Antoni C, Keenan GF, et al. Outcome of pregnancy in women receiving infliximab for the treatment of Crohn’s disease and rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:2385–92.

Matro R, Martin CF, Wolf D, et al. Exposure concentrations of infants breastfed by women receiving biologic therapies for inflammatory bowel diseases and effects of breastfeeding on infections and development. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:696–704.

de Lima A, Zelinkova Z, Mulders AG, et al. Preconception care reduces relapse of inflammatory bowel disease during pregnancy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:1285-1292 e1.

Reich J, Guo L, Groshek J, et al. Social media use and preferences in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019;25:587–91.

Martinez B, Dailey F, Almario CV, et al. Patient understanding of the risks and benefits of biologic therapies in inflammatory bowel disease: insights from a large-scale analysis of social media platforms. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:1057–64.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

Dr. Kushner received an American College of Gastroenterology Pilot Research Award to support this project.

Conflict of interest

TK has participated in an advisory board for Gilead. BS has received consulting fees from 4D Pharma, AbbVie, Allergan, Amgen, Arena Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Boston Pharmaceuticals, Capella Biosciences, Celgene, Celltrion Healthcare, enGene, Ferring, Genentech, Gilead, Hoffmann-La Roche, Immunic, Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, Janssen, Lilly, Lyndra, MedImmune, Morphic Therapeutic, Oppilan Pharma, OSE Immunotherapeutics, Otsuka, Palatin Technologies, Pfizer, Progenity, Prometheus Laboratories, Redhill Biopharma, Rheos Medicines, Seres Therapeutics, Shire, Synergy Pharmaceuticals, Takeda, Target PharmaSolutions, Theravance Biopharma R&D, TiGenix, and Vivelix Pharmaceuticals; honoraria for speaking in continuing medical education (CME) programs from Takeda, Janssen, Lilly, Gilead, Pfizer, and Genentech; and research funding from Celgene, Pfizer, Takeda, Theravance Biopharma R&D, and Janssen. UM has received consulting fees from Janssen, AbbVie, Takeda, Gilead, and Bristol Myers Squibb and research funding from Pfizer, Celgene, and Genentech. SS has received speaker fees from Merck Sharpe & Dohme, AbbVie, Dr. Falk Pharmaceuticals, Takeda, and Janssen and educational grants from Takeda and Janssen. AA has received consulting fees from Kyn Therapeutics and Sun Pharma. CH has received advisory/consultant fees from AbbVie, Galen Atlantica, Genentech, Janssen, Pfizer, Salix, and Takeda; grant support from Pfizer; and honoraria for speaking from AbbVie, Medical Education Network, Prova Education, Vindico, and Imedex. MB has received research funding from Janssen, GlaxoSmithKline, and Takeda; has served as a consultant for Janssen, AbbVie, Bristol Myers Squibb, and Pfizer; and has received honorarium for participation in a CME program sponsored by AbbVie. AF has received salary or subcontractor research support fees supported in part by research funding from AbbVie, Janssen, Pfizer, Grifols, GlaxoSmithKline, Genentech, Lilly, and Amgen. FRJ has made available online a detailed listing of financial disclosures: https://dcri.org/about-us/conflict-of-interest.

Availability of data and material

The survey is provided in the ESM. Data are available upon request.

Ethics approval

The study and final survey instrument were approved by all participating institutions. Ethics approval was obtained at each institution under each institutional review board under expedited procedure.

Author contributions

AF assisted with the conduct of the study and designing the statistical analysis, performed data analysis, interpreted the data, and edited the manuscript. TK assisted with the research protocol and the conduct of the study, interpreted the data, and edited the manuscript. FRJ assisted with the research protocol, the conduct of the study, and designing the statistical analysis; performed data analysis; interpreted the data; and edited the manuscript. BS assisted with the research protocol, planning the study, and interpretation of data, and edited the manuscript. UM assisted with planning the study and edited the manuscript. SS assisted with the study design, the research protocol, interpretation of data, and manuscript editing. AA assisted with data collection and edited the manuscript. CH assisted with data collection and edited the manuscript. MB assisted with writing the research protocol and the planning and conduct of the study, assisted in data analysis, interpreted the data, and drafted the manuscript. She is the guarantor and affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported.

Consent to participate

All potential participants were mailed a letter with an invitation to the online survey and a unique code. Given the mailed nature of the study, written or verbal consent was not obtained. Consent was implied with completion of the study; and it was emphasized in the invitation letter that a) participation was voluntary; b) participation was confidential; c) they could quit the study at any time without penalty; d) decisions not to participate would not affect their status as a patient at the participating institution; and e) all results would be presented in aggregate and no individual identifiers would be used.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Code availability

Data is available upon request.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kushner, T., Fairchild, A., Johnson, F.R. et al. Women’s Willingness to Accept Risks of Medication for Inflammatory Bowel Disease During Pregnancy. Patient 15, 353–365 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-021-00561-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-021-00561-9