Abstract

Introduction

Antifungal stewardship (AFS) programs are recognized to contribute to optimizing antifungal prescribing for treatment and prophylaxis. However, only a small number of such programs are implemented. Consequently, evidence on behavioral drivers and barriers of such programs and learnings from existing successful AFS programs is limited. This study aimed to leverage a large AFS program in the UK and derive learnings from it. The objective was to (a) investigate the impact of the AFS program on prescribing habits, (a) use a Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) based on the COM-B (Capability, Opportunity, and Motivation for Behavior) to qualitatively identify drivers and barriers for antifungal prescribing behaviors across multiple specialties, and (c) semiquantitatively investigate trends in antifungal prescribing habits over the last 5 years.

Methods

Qualitative interviews and a semiquantitative online survey were conducted across hematology, intensive care, respiratory, and solid organ transplant clinicians at Cambridge University Hospital. The discussion guide and survey used were developed to identify drivers of prescribing behavior, based on the TDF.

Results

Responses were received from 21/25 clinicians. Qualitative outcomes demonstrated that the AFS program was effective in supporting optimal antifungal prescribing practices. We found seven TDF domains influencing antifungal prescribing decisions—five drivers and two barriers. The key driver was collective decision-making among the multidisciplinary team (MDT) while key barriers were lack of access to certain therapies and fungal diagnostic capabilities. Furthermore, over the last 5 years and across specialties, we observed an increasing tendency for prescribing to focus on more targeted rather than broad-spectrum antifungals.

Conclusions

Understanding the basis for linked clinicians’ prescribing behaviors for identified drivers and barriers may inform interventions on AFS programs and contribute to consistently improving antifungal prescribing. Collective decision-making among the MDT may be leveraged to improve clinicians’ antifungal prescribing. These findings may be generalized across specialty care settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

Inappropriate antifungal use may contribute to the emergence of resistant fungal species. |

Antifungal stewardship (AFS) programs help optimize antifungal prescribing for treatment and prophylaxis. |

This study explored one of the most comprehensive AFS programs developed in the UK at the Cambridge University Hospital (CUH) to (i) qualitatively investigate the use of a Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) based on the COM-B (Capability, Opportunity, and Motivation for Behavior) to identify drivers and barriers of clinicians’ antifungal prescribing behaviors, and (ii) semiquantitatively investigate trends in antifungal prescribing habits over the last 5 years. |

What was learned from the study? |

Qualitative outcomes demonstrated that several (seven) TDF domains influenced antifungal prescribing decisions: (i) five drivers with collective decision-making among the multidisciplinary team (MDT) being the key driver and (ii) two barriers with the lack of access to certain therapies being the key barrier. |

Semiquantitative analysis indicates that the use of antifungal therapies at CUH had increased over the last 5 years across all specialties interviewed with more targeted use instead of broad-spectrum prescribing. |

These insights may inform potential impact of interventions that may be considered for implementation as part of successful AFS programs. |

Introduction

Optimizing treatment for and prevention of invasive fungal infections (IFIs) is particularly important because of high mortality rates, challenges in obtaining a timely diagnosis, and the complexity of drugs and patient groups involved [1, 2]. Excessive use of antifungals is associated with toxicity and it is believed that a high rate of inappropriate prescribing contributes to the emergence of resistant fungal species [1, 2]. There is an opportunity to manage these threats through more judicious use of antifungals [3, 4].

Antimicrobial stewardship programs targeting antifungals, i.e., antifungal stewardship (AFS) programs, help optimize antifungal prescribing for both treatment and prophylaxis [5,6,7,8,9,10] through improvements in drug selection [9, 11], dosing [12], appropriateness of antifungal use [13], and duration of therapy [9, 12]. Such programs were shown to reduce the incidence of clinically relevant drug–drug interactions (DDIs) [12], antifungal adverse drug reactions [14], and healthcare costs [10, 15, 16]. Despite these benefits, stewardship programs are overwhelmingly focused on antibacterials rather than antifungals. An electronic survey conducted across National Health Service (NHS) acute trusts within England in 2016 revealed that only 11% (5/47) of trusts undertook dedicated AFS programs compared to 98% for antibacterial stewardship programs [17]. Potential reasons for this are (a) for antifungal treatment, clinicians reported less familiarity with fungal infections while patients with confirmed/suspected fungal infections generally have multiple comorbidities to consider and/or are extremely sick [17], (b) for antifungal prophylaxis, there is wide variability by institution, prescriber, patient type, and disease state when prioritizing prophylaxis in immunocompromised populations at high risk of IFIs [18].

To address inappropriate antifungal prescribing, the NHS Improving Value Antifungal Stewardship Project was initiated in 2018 across NHS acute trusts within England to optimize the use of antifungals, improve patient outcomes, and preserve the future effectiveness of antimicrobials [17, 19]. As attention and investment in AFS increases, it is important to assess existing programs and derive learnings from their experiences.

AFS programs have been assessed on the basis of clinical outcome measures but psychosocial assessments to understand behavior change are acknowledged as essential for program success. There has been a demand for the more explicit use of Behavior Change Theory (BCT) to identify behavioral determinants and influencers of change (drivers and barriers) to inform interventions [20]. The Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) based on COM-B (i.e., Capability, Opportunity, and Motivation for Behavior) separates psychosocial drivers of behavior into domains covering a spectrum of theoretical determinants (knowledge, memory, attention, and decision-making, etc.). TDF provides a theoretical lens through which to view the cognitive, affective, social, and environmental influences on behavior. To our knowledge, there are no previous studies that evaluated the AFS programs with qualitative and semiquantitative approaches, using BCT across multiple specialties [21].

This study explored a well-established AFS program in the UK using qualitative assessment followed by a survey to obtain semiquantitative insights on prescribing behaviors across hematology, intensive care unit (ICU), respiratory, and solid organ transplant (SOT) clinicians. This study aimed to (a) investigate the awareness of the AFS program and the activities with the largest impact on prescribing habits across specialties; (b) use a TDF based on the COM-B to qualitatively identify drivers and barriers for antifungal prescribing behaviors across the four clinical specialties which are typically associated with higher rates of antifungal use; and (c) semiquantitatively investigate any trends in antifungal prescribing habits over the last 5 years (i.e., volume/amount and variety/variability of therapies, and impact of COVID-19). These insights may help to inform the design and implementation of AFS programs to close the gaps found across NHS trusts in England and elsewhere.

Methods

Ethic Statement

The study was conducted in compliance with the approved protocol and adhered to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki, the sponsor’s standard operating procedures (SOPs), and other regulatory requirements. The research protocol for this study was submitted to the Cambridge University Hospital (CUH) NHS Foundation Trust Research Ethics Committee (Ref. 21/HRA/460) and Integrated Research Approval System (IRAS) confirmation was received in October 2021.

Recruitment of Participants

For recruitment of participating clinicians, the study was publicized twice in the CUH online daily bulletin and emails, and reminders were sent to target clinicians. Study details were also conveyed verbally by the chief investigator and consultant microbiologist (D.A.E.) directly to clinicians during ward rounds. Additionally, the principal antimicrobial pharmacist (C.M.) contacted the lead clinical pharmacist teams of all the specialties, to publicize the study and clinicians were invited to participate. This study planned to recruit 25 clinicians at CUH with five clinicians per specialty type to provide a robust qualitative and semiquantitative assessment of decision drivers, and an equal allotment across groups to enable comparison across them. Eligible participants were initially identified by the chief investigator and principal antimicrobial pharmacist and study coordinator (C.M.), based on their professional network within CUH, who also gauged interest in participating in the research.

Study Design

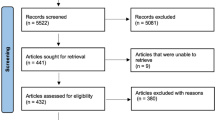

Clinician respondents from CUH completed a qualitative telephone interview and a semiquantitative online survey (Fig. 1). Data were collected between January and March 2022. Patient involvement was not required.

Setting

CUH is a large, single-site, tertiary teaching hospital in the East of England with 1100 beds, 70,000 inpatient admissions, and 170,000 total admissions per annum. The hospital offers several specialist services, including solid organ transplantation (SOT; multi-visceral, liver, and renal +/- pancreas transplants), hematology/oncology (including stem cell transplantation), and neurosurgery. Their AFS program was launched in 2013 for all inpatients receiving high-cost antifungals and clinicians provided their perspectives on the current impact of the program, and any notable trends over the past 5 years (i.e., from 2018 to 2022).

Qualitative Interview

An interview discussion guide was developed on the basis of the TDF (Supplemental Table 1). Factors affecting clinicians’ decision-making were informed by published literature [20, 22,23,24] and the expertise of the research team. On the basis of the initial output after completing the first two pilot interviews, the interview guide was rearranged to separate discussions on antifungal prophylaxis and treatment to streamline the discussion.

Interview Procedure

Emails were sent out to hematology, oncology, SOT, respiratory, and ICU clinicians at CUH and a participant information sheet and consent form were emailed to interested clinicians. Oncologists were later removed from the study plan as a result of recruitment difficulties, and a nearly equal number of clinicians were recruited from the remaining four specialties. Upon consent, a qualitative 1:1 telephone interview was scheduled and conducted via the Zoom platform by experienced researchers (C.K., R.M., and K.G.). The identity of the clinician was concealed and their responses to interview questions were anonymized. Qualitative data was summarized into overall findings.

Assessment of Behavior Change

The discussion guide used in the qualitative research was developed to identify drivers of clinicians’ prescribing behavior, based on the TDF (Supplementary Table 1). These sources of behavioral change were categorized as (1) Capability—Psychological, (2) Opportunity—Social and Physical, (3) Motivation—Automatic and Reflective [20, 22,23,24]. The methodology used in this study is consistent with the application of behavioral theory used in other qualitative studies describing antifungal prescribing habits and focused on the evaluation of intervention design in the context of healthcare settings as described above [20, 22].

Semi-Quantitative Survey

To obtain quantitative insights, the interviews were followed by a 10-min online semiquantitative survey designed for self-completion to measure clinicians’ antifungal prescribing behaviors. This survey was designed to measure the importance/impact of drivers of antifungal prescribing behavior, including the impact of CUH AFS program initiatives (Fig. 1).

Data Analysis

Qualitative and semiquantitative analyses were performed in the context of antifungal prescribing habits for prophylaxis and treatment separately. Further details of data analysis are presented in Fig. 1. Qualitative interview transcripts were analyzed to identify drivers and barriers in antifungal prescribing. Semiquantitative online survey responses were captured, quantified, and analyzed for trends in antifungal prescribing across specialties. Output from this research was mapped to the TDF framework.

Results

Participants

Of total clinicians approached, 21/25 (84%) clinicians participated and were interviewed. Twelve were consultants (i.e., senior) and nine were registrars (junior) and had been in their role for between 1 month and 17 years. In terms of specialty, there were six hematology (two consultants, four registrars), six SOT (four consultants, two registrars), five ICU (four consultants, one registrar), and four respiratory (two consultants, two registrars) clinicians (Table 1). The number of registrars and consultants varied by the specialty; however, aggregate responses from total clinicians recruited per specialty were presented. Clinicians routinely saw around 40 to 400 or more patients per month. One respiratory clinician was unable to complete the online survey before the study closed and therefore responses from 20/21 (95%) clinicians were included in the semiquantitative survey.

The sections below describe qualitative and semiquantitative analyses of the data. Qualitative analysis included AFS activities impacting prescribing habits and general barriers and drivers of AFS. Semiquantitative analysis of data included trends in antifungal prescribing habits over the last 5 years.

Qualitative Analysis

Antifungal Stewardship Activities with the Largest Impact on Prescribing Habits

Clinicians were asked specific questions to understand the impact of the AFS program on prescribing habits (Supplementary Table 1). For hematology, ICU, and SOT clinicians, the AFS program was generally thought to have had a positive impact on antifungal prescribing habits, resulting in reduced antifungal resistance and cost savings. For both prophylaxis and treatment, and across all specialties, the AFS program activity with the largest impact on prescribing habits was specialist consultations at the daily/weekly multidisciplinary team (MDT) meetings (Table 2).

In the respiratory setting, given the lack of patients receiving antifungal therapy, the impact of the AFS program was thought to be limited to a small subset of patients, and therefore the overall impact of the AFS activities was perceived to be minimal.

Factors Influencing the Prescribing of Prophylaxis and Treatment

Data collected from 42 interview questions were mapped to 14 TDF domains (Supplemental Table 1), through which seven TDF domains were identified as factors influencing appropriate antifungal prescribing and categorized under general drivers and barriers for each specialty. TDF domains were then mapped onto the COM-B model along with interview quotes from specific clinicians (Supplementary Table 2). Each quote is followed by a bracket with letters that indicate the specialty. Specialty-specific breakdowns of the drivers/barriers by TDF domains are provided in Table 3.

Five drivers along with two barriers identified were mapped to the COM-B domains and are described below in detail as TDF (COM-B).

General Drivers

Knowledge (Capability—Psychological) Knowledge of local level guidelines was used in prophylaxis (in the hematology, ICU, and SOT settings) and in treatment of clinically confirmed or suspected fungal infections (in the hematology and SOT settings). For ICU clinicians, none of the responses were associated with this TDF. Respiratory clinicians did not have local guidelines; hence, knowledge of prescribing habits gained from medical training/previous clinical experience played a key role in prescribing decisions across both the prophylactic and treatment settings (Q1–Q2).

Memory, Attention, and Decision-Making (Capability—Psychological) For prophylaxis prescribing habits, the memory of the previous experience was used to guide respiratory clinicians’ prescribing habits. For other specialties, none of the responses were associated with this TDF.

Treatment decisions were made through consideration of several sources of information such as patient history, DDIs, underlying diagnosis, input from microbiology, and initial diagnostic test results in the absence of a clinically confirmed diagnosis across all specialties (Q3).

Behavior Regulation (Capability—Psychological) For both prophylaxis and treatment, and across all specialties investigated, monitoring, auditing, and reviewing of prescribing decisions by MDT (included microbiologists and pharmacists) as a part of AFS program was a key driver of prescribing appropriateness. Involving MDT as an essential component of an AFS program may have positive implications (Q4).

Social Influences (Opportunity—Social) Social influences was an important behavioral component across all specialties. For prophylaxis, MDT provided input by monitoring the appropriateness of therapy (dose/duration) as described above. ICU clinicians maintained the decisions provided by parent team when a patient (who was already on antifungal therapy) was transferred to the ICU.

When prescribing for treatment of infection, specialist consultations at the daily/weekly MDT meeting was a key driver (more than published guidelines), especially in ICU settings. For the choice of therapy for treating an infection, inputs were based on the clinical scenario and results of available diagnostic tests across all specialties.

Discussion with the MDT in the daily meetings informed collective decision-making around prescribing (prophylaxis and treatment). Specifically in respiratory settings where there are less guidelines, input from the MDT and senior colleagues had a significant influence on prescribing behavior (prophylaxis and treatment), particularly for junior clinicians (Q5–Q6).

Beliefs About Consequences (Motivation—Reflective) Knowledge of the severity of fungal infections drives antifungal prescribing (prophylaxis and treatment) in the hematology, SOT, and ICU settings. Prophylactic prescribing, in hematology and SOT settings, was more common given their knowledge of the high-risk, immunocompromised patients and the severity of fungal infections. As observed in responses from the ICU clinicians, MDT meetings had a greater impact and were conducted more frequently (daily vs. weekly) than in other specialties.

While treating fungal infections in the hematology, ICU, and SOT settings, a preference was observed for initiating treatment based on clinical suspicion, which was largely due to clinicians’ knowledge of patient mortality/morbidity caused by invasive fungal infections (IFIs) (Q7–Q9).

Respiratory clinicians in our sample at any level of experience and seniority had limited knowledge and experience with IFIs since IFIs were rarely encountered in their patients.

General Barriers

Environmental Context and Resources (Opportunity—Physical) A lack of access to certain therapies on the NHS formulary was generally highlighted as a barrier to prescribing habits (prophylaxis and treatment) across all specialties investigated except SOT settings. For SOT clinicians in prophylaxis prescribing, none of the responses were associated with this TDF.

For treatment prescribing, several issues were highlighted concerning diagnostic tests (turnaround time, accuracy, and in some cases availability of diagnostics test) which also acted as a general barrier. In respiratory settings, the lack of local level guidelines to guide antifungal prescribing was also perceived as a barrier to appropriate prescribing (prophylaxis and treatment) (Q10–Q11).

Beliefs About Capability (Motivation—Reflective) For prophylaxis and treatment prescribing, a lack of training for situations not encompassed by guidelines has been highlighted as a barrier to prescribing habits, especially by more junior hematology and SOT clinicians (Q12).

Senior respiratory and SOT clinicians were more comfortable in prescribing before receiving all diagnostic information, given their previous clinical experience. The majority of the senior SOT clinicians were confident in clinical capabilities, and prescribed on the basis of their own clinical experience, even in case of disagreement with the MDT team. For junior respiratory clinicians, a lack of belief in their capability was observed to influence prescribing habits, as they would typically have to seek input from more senior clinicians before deciding on prescribing. For ICU clinicians, none of the responses were associated with this TDF.

Semi-Quantitative Analysis

Trends in Prescribing Antifungals Over the Last 5 Years

Clinicians were administered a survey with specific questions to understand the trends in prescribing antifungals over the last 5 years (Supplementary Table 1). Additionally, the clinicians’ response to the “COVID-19 has influenced how I prescribe antifungal therapies for prophylaxis on the rating scale over the last 5 years” is also explored (Supplemental Fig. 1 under supplemental data).

Use and Targeted Use of Antifungal Therapies

Based on the clinicians’ response to “my use of antifungal therapies has increased over the previous 5 years”, the average score for use of antifungal therapies was 3.8, 3.8, 4.7, and 4 for hematology, ICU, respiratory, and SOT, respectively. There was near universal agreement across specialties that the volume of antifungal therapy had increased over the last 5 years (Fig. 2a) and this may be attributed to the possible increased awareness/education around available antifungals (Q13–Q14).

Trends in prescribing antifungals over the last 5 years. a Use of antifungal therapies over the last 5 years. b Targeted use of antifungal therapies over the last 5 years. Participants were asked to answer survey questions on a scale of 1 to 5: completely agree = 1; somewhat agree = 2; neither agree or disagree = 3; somewhat agree = 4; completely agree = 5. Numerical average score of all the individual scores on the rating scale was calculated for each question and each specialty. ICU intensive care unit, SOT solid organ transplant

Based on the clinicians’ response to “my use of antifungal therapies has become more targeted over the previous 5 years”, the average score for targeted use of antifungal therapies was 3.3, 4, 4.3, and 3.3 for hematology, ICU, respiratory, and SOT, respectively. This indicates that the use of antifungal therapies is perceived to have become more targeted over the last 5 years, especially by ICU and respiratory clinicians (Fig. 2b). ICU clinicians stated that they now generally focus prophylaxis on patients at high risk of developing an IFI. The respiratory clinician stated that antifungal therapy remains rare, but the choice of therapy is more targeted. The level of agreement with the trend varied for hematology and SOT clinicians.

Additionally, for respiratory clinicians, the average score was the highest (prophylaxis, 4.7; treatment, 4.3) among all specialties, indicating near-complete agreement with the statement that their use of antifungal therapies increased over the past 5 years (Fig. 2, Q15–Q16).

Use of a Variety of Therapies for Prophylaxis and Treatment

The average score for “I use a greater variety of prophylaxis antifungal therapies now compared to 5 years ago” was 4, 4, 3.7, and 2.8 for hematology, ICU, respiratory, and SOT, respectively. Clinicians from all specialties except SOT generally agreed that they used a wider variety of prophylaxis antifungals when compared to 5 years ago (Fig. 3a). The general consensus from SOT clinicians was that when prescribing for prophylaxis, they favored the same therapies although new ones were approved, given their familiarity with the clinical profile (Q17–Q18).

Use of a variety of therapies for prophylaxis and in the treatment setting. a Use of a variety of therapies for prophylaxis. b Use of a variety of therapies in treatment settings. Participants were asked to answer survey questions on a scale of 1 to 5: completely agree = 1; somewhat agree = 2; neither agree or disagree = 3; somewhat agree = 4; completely agree = 5. Numerical average score of all the individual scores on the rating scale was calculated for each question and each specialty. ICU intensive care unit, SOT solid organ transplant

The average score for “I use a greater variety of therapies when treating fungal infections now compared to 5 years ago” was 3.8, 4.4, 4.3, and 4.3 for hematology, ICU, respiratory, and SOT, respectively. This indicates a universal agreement across specialties that clinicians were prescribing a wider variety of therapies, compared to 5 years ago. This increase in the variety of antifungal therapies prescribed is likely driven by the additional treatment options available to clinicians, which are approved for specific fungal infections (vs. broad-spectrum treatments) (Fig. 3b, Q19–Q20).

Discussion

Clinicians face several challenges and balance a range of different patient needs when deciding to prescribe antifungals for prophylaxis or for treatment of confirmed/suspected IFIs. In this study, the effect of an AFS program on antifungal prescribing behavior across four specialties was assessed using the TDF and COM-B model. Trends in antifungal prescribing habits over the last 5 years were also assessed, and the extent of variability in antifungal prescribing was determined.

Impactful AFS activities observed in our study lay within five main TDF domains. For example, specialist consultations may lie within the TDF domain of behavior regulation (COM-B: Capability–Psychological), review by the AFS team within the TDF domain of social influence (COM-B: Opportunity–Social), and bespoke training within the TDF domain of knowledge (COM-B: Capability–Psychological).

We found several elements regarding the AFS program, and the behaviors involved in antifungal prescribing. First, our investigation showed that across specialties, clinicians find the AFS program very useful in supporting optimal antifungal prescribing practices. This is in line with previous research that shows potential cost-savings in antifungal expenditure and improving patient management were benefits motivating the implementation of AFS programs [17]. It is interesting to note that the AFS program was perceived to be impactful across the three specialties of hematology, ICU, and SOT, while for respiratory, where fewer patients received antifungal therapy, the overall impact of the AFS program activities was perceived to be more limited.

Second, we found seven TDF domains influencing antifungal prescribing decisions, identifying five key drivers (behavior regulation; social influences; knowledge; beliefs about consequences; and memory, attention, and decision-making) and two barriers (environmental context and resources, and belief in capabilities). While drivers and barriers of AFS have not been identified earlier, previous studies on antimicrobial prescribing have found similar results. For example, a study conducted in Australia identified nine key domains that influenced delayed antibiotic prescribing including memory, attention, and decision-making processes; beliefs about consequences; and social influences were also identified as key influencers for prescribing [25]. Furthermore, in a study conducted in 12 hospitals in Qatar, environmental context and resources, and social influences were identified as useful barrier targets for behavior change interventions to improve antimicrobial prescribing habits [26].

Third, we found the key driver was collective decision-making among the MDT while the key barriers are lack of access to certain therapies on the NHS formulary and diagnostic capabilities (turnaround time, accuracy, and in some cases availability of diagnostics test). Our findings are in line with another recent study from Australia that identified the same driver and barrier [21]. A study from our institution was performed between 2013 and 2015 to assess the impact of the introduction of a new diagnostic pathway involving galactomannan and aspergillus PCR [27]. Despite availability of diagnostic tests during this prior study, uncertainty about their accuracy is suggested such that hematologists often ignored negative serum galactomannan and PCR results (i.e., they continued treatment anyway) but believed positive bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) galactomannan results (when therapy was typically switched from liposomal amphotericin B to voriconazole [15]). While Martinelli et al. did not assess turnaround time [27], it was later recognized as being prolonged by Micallef et al. [17]. Diagnostic capabilities were identified as a barrier to antifungal prescribing in the current study.

Fourth, we found that the use of antifungal therapies at CUH was reported to have increased over the last 5 years across all specialties interviewed with more targeted instead of broad-spectrum prescribing of antifungal prophylaxis, especially for ICU and respiratory clinicians, but less so for SOT clinicians. Furthermore, our explorations show that the prescribing habits of ICU clinicians were affected by COVID-19; however, other specialties were less affected.

This study has several strengths. First, the AFS program at CUH is well established with a number of studies describing its outcomes and successes [5, 12, 14, 15] and provides a good sample for this qualitative study assessing the impact of the AFS program in the context of a behavior change framework. The drivers and barriers identified by this TDF-based assessment of program impact may extend to similar healthcare settings. Second, both semiquantitative and qualitative approaches were used to understand influences (drivers and barriers) on antifungal prescribing behavior, with a theory-driven approach to clarify core factors that may be targeted in interventions to support appropriate antifungal prescribing. Third, clinicians were from four different clinical specialties, selected on the basis of high antifungal prescription rates. The factors we identified may be targeted most successfully in multispecialty healthcare settings involving clinicians from different specialties, owing to the ease of knowledge sharing in such circumstances.

Our study had some limitations. First, sample sizes were limited; hence, this study may not reflect the overall prescribing behavior of practicing clinicians. Second, clinicians in this study were recruited from a single multidisciplinary hospital and local norms may differ elsewhere. Future studies comparing the TDF domains and behavioral factors identified across multiple hospitals would strengthen the analysis of drivers and barriers for antifungal prescribing behavior. Third, as inherent with all qualitative research, our interviews were restricted to those clinicians who agreed to participate, which may reflect a group that is more interested in and well informed about IFIs in the immunocompromised population. Social desirability bias may have occurred, since participants may have responded in a manner viewed as favorable by the interviewer.

Possible Implications for Clinicians and Policymakers

Recently, consensus guidelines for AFS, surveillance, and infection prevention have highlighted knowledge, local guidelines, and education as some of the essential components and key interventions of an AFS program [28]. However, successful implementation of AFS requires an understanding of the drivers and barriers of prescribing behaviors to improve antifungal prescribing. Previous work has supported use of an MDT as part of AFS programs to improve patient management [15] and our findings reveal that clinicians themselves find that MDT and dedicated AFS teams are among the most impactful elements of an AFS program. This suggests that the key to successful AFS program implementation is the optimal use of resources balancing staff time and expertise. Similarly, while previous work did not find benefit in teaching events and e-learning programs for AFS [17], clinicians reported that bespoke training is impactful. This suggests that limited resources may be allocated less on “classroom-type” general training activities and more on facilitating MDT and dedicated AFS team interactions to share expertise.

Conclusion

Understanding the basis for the linked clinicians’ prescription behaviors for identified drivers and barriers may inform interventions for AFS programs to optimize antifungal prescribing behaviors. We believe that discussions in MDT meetings can sustain behavior change and improve clinicians’ antifungal prescribing. The principles applied here may be generalizable to a range of other multispecialty healthcare centers.

References

Alegria W, Patel PK. The current state of antifungal stewardship in immunocompromised populations. J Fungi (Basel). 2021;7(5):352.

Hamdy RF, Zaoutis TE, Seo SK. Antifungal stewardship considerations for adults and pediatrics. Virulence. 2017;8(6):658–72.

Perlin DS, Rautemaa-Richardson R, Alastruey-Izquierdo A. The global problem of antifungal resistance: prevalence, mechanisms, and management. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17(12):e383–92.

Pfaller MA. Antifungal drug resistance: mechanisms, epidemiology, and consequences for treatment. Am J Med. 2012;125(1 Suppl):S3-13.

Santiago-García B, Rincón-López EM, Ponce Salas B, et al. Effect of an intervention to improve the prescription of antifungals in pediatric hematology-oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2020;67(4):e27963.

Valerio M, Rodriguez-Gonzalez CG, Muñoz P, et al. Evaluation of antifungal use in a tertiary care institution: antifungal stewardship urgently needed. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69(7):1993–9.

Samura M, Hirose N, Kurata T, et al. Support for fungal infection treatment mediated by pharmacist-led antifungal stewardship activities. J Infect Chemother. 2020;26(3):272–9.

Apisarnthanarak A, Yatrasert A, Mundy LM. Impact of education and an antifungal stewardship program for candidiasis at a Thai tertiary care center. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31(7):722–7.

Mondain V, Lieutier F, Hasseine L, et al. A 6-year antifungal stewardship programme in a teaching hospital. Infection. 2013;41(3):621–8.

Andruszko B, Dodds AE. Antifungal stewardship: an emerging practice in antimicrobial stewardship. Curr Clin Microbiol Rep. 2016;3(3):111–9.

Benoist H, Rodier S, de La Blanchardière A, et al. Appropriate use of antifungals: impact of an antifungal stewardship program on the clinical outcome of candidaemia in a French University Hospital. Infection. 2019;47(3):435–40.

Lachenmayr SJ, Strobach D, Berking S, Horns H, Berger K, Ostermann H. Improving quality of antifungal use through antifungal stewardship interventions. Infection. 2019;47(4):603–10.

Kara E, Metan G, Bayraktar-Ekincioglu A, et al. Implementation of pharmacist-driven antifungal stewardship program in a tertiary care hospital. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2021;65(9):e0062921.

Ito-Takeichi S, Niwa T, Fujibayashi A, et al. The impact of implementing an antifungal stewardship with monitoring of 1–3, β-D-glucan values on antifungal consumption and clinical outcomes. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2019;44(3):454–62.

Micallef C, Aliyu SH, Santos R, Brown NM, Rosembert D, Enoch DA. Introduction of an antifungal stewardship programme targeting high-cost antifungals at a tertiary hospital in Cambridge, England. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70(6):1908–11.

Whitney L, Al-Ghusein H, Glass S, et al. Effectiveness of an antifungal stewardship programme at a London teaching hospital 2010–16. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2018;74(1):234–41.

Micallef C, Ashiru-Oredope D, Hansraj S, et al. An investigation of antifungal stewardship programmes in England. J Med Microbiol. 2017;66(11):1581–9.

Vazquez L. Antifungal prophylaxis in immunocompromised patients. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2016;8(1): e2016040.

Whitney L, Hall N, Leach M, NHS England. Improving value in specialised services. Antifungal stewardship implementation pack. 2019. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/PSS1-meds-optimisation-trigger-5-antifungal-stewardship-implementation-pack-v7.pdf. Accessed Jan 2023.

Courtenay M, Rowbotham S, Lim R, Peters S, Yates K, Chater A. Examining influences on antibiotic prescribing by nurse and pharmacist prescribers: a qualitative study using the Theoretical Domains Framework and COM-B. BMJ Open. 2019;9(6):e029177.

Ananda-Rajah MR, Fitchett S, Ayton D, et al. Ushering in antifungal stewardship: perspectives of the hematology multidisciplinary team navigating competing demands, constraints, and uncertainty. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2020;7(6):168.

Atkins L, Francis J, Islam R, et al. A guide to using the Theoretical Domains Framework of behaviour change to investigate implementation problems. Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):77.

Shah N, Castro-Sánchez E, Charani E, Drumright LN, Holmes AH. Towards changing healthcare workers’ behaviour: a qualitative study exploring non-compliance through appraisals of infection prevention and control practices. J Hosp Infec. 2015;90(2):126–34.

Hayward GN, Moore A, McKelvie S, Lasserson DS, Croxson C. Antibiotic prescribing for the older adult: beliefs and practices in primary care. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2019;74(3):791–7.

Sargent L, McCullough A, Del Mar C, Lowe J. Using theory to explore facilitators and barriers to delayed prescribing in Australia: a qualitative study using the Theoretical Domains Framework and the Behaviour Change Wheel. BMC Fam Pract. 2017;18(1):20.

Talkhan H, Stewart D, McIntosh T, et al. Investigating clinicians’ determinants of antimicrobial prescribing behaviour using the Theoretical Domains Framework. J Hosp Infect. 2022;122:72–83.

Martinelli AW, Wright CB, Lopes MS, et al. Introducing biomarkers for invasive fungal disease in haemato-oncology patients: a single-centre experience. J Med Microbiol. 2022;71:7.

Khanina A, Tio SY, Ananda-Rajah MR, et al. Consensus guidelines for antifungal stewardship, surveillance and infection prevention. Intern Med J. 2021;51(1):18–36.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This work was supported by Pfizer Inc. CM received specific funding from Pfizer to help lead the delivery of this project. Oliver Wyman (sponsored by Pfizer) conducted physician surveys and collated data. Participants were offered an incentive from Pfizer. DAE received no specific funding. Journal rapid service fee is funded by Pfizer Inc.

Medical Writing Assistance

Under the direction of the authors, Varkha Agrawal (Ph.D., CMPP™) provided medical writing support; Kripa Madnani (Ph.D., CMPP™) and Sonia Philipose (Ph.D., CMPP™) provided editorial support (all employees of Pfizer). The authors are thankful to the clinicians who participated in this research.

Author Contributions

Anita H Sung, David A Enoch, Christianne Micallef, Rahael Maladwala, and Kate Grady: Conceptualization; Rahael Maladwala, Kate Grady, and Christian Kouppas: Data curation and software; Maria Gheorghe, Rahael Maladwala, Kate Grady, and Christian Kouppas: Formal analysis; Anita H Sung and Christianne Micallef: Funding acquisition; David A Enoch, Rahael Maladwala, Kate Grady, and Christian Kouppas: Investigation; Anita H Sung, David A Enoch, Christianne Micallef, Rahael Maladwala, and Kate Grady: Methodology; Anita H Sung, Christianne Micallef, Maria Gheorghe, Rahael Maladwala, Kate Grady, and Christian Kouppas: Project administration; Anita H Sung and Christianne Micallef: Resources; Anita H Sung, Christianne Micallef, Rahael Maladwala, and Kate Grady: Supervision; Christianne Micallef: Validation; Christianne Micallef, Rahael Maladwala, Kate Grady, and Christian Kouppas: Visualization; All authors: Writing-critical review and editing; approval of final version of this manuscript.

Disclosures

Anita H Sung and Maria Gheorghe are current employees of Pfizer and may hold stock/stock options with Pfizer. David A Enoch and Christianne Micallef are employees of Cambridge University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust. Rahael Maladwala, Kate Grady, and Christian Kouppas are consultants. Rahael Maladwala and Christian Kouppas were previously affiliated with Oliver Wyman, New York, USA at the time of submission, and there are no new affiliations to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The study was conducted in compliance with the approved protocol and adhered to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki, the sponsor’s SOPs, and other regulatory requirements. The research protocol for this study was submitted to the Cambridge University Hospital (CUH) NHS Foundation Trust Research Ethics Committee (Ref. 21/HRA/460) and Integrated Research Approval System (IRAS) confirmation was received in October 2021. Written informed consent was obtained from clinicians who participated in this survey- and interview-based study. No clinical interventions were conducted.

Data Availability

The data sets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Micallef, C., Sung, A.H., Gheorghe, M. et al. Using Behavior Change Theory to Identify Drivers and Barriers for Antifungal Treatment Decisions: A Case Study in a Large Teaching Hospital in the East of England, UK. Infect Dis Ther 12, 1393–1414 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40121-023-00796-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40121-023-00796-z