Abstract

Ma’an Qiao Village, a Dai and Yi ethnic minority-based community in Sichuan Province, China sustained complete infrastructure devastation during the 2008 Panzhihua earthquake. Health emergency and disaster risk management (Health-EDRM) education intervention programs were implemented in 2010 and 2011. This serial cross-sectional survey study aimed to examine the immediate and long-term impacts of the Health-EDRM interventions in this remote rural community. The findings demonstrate knowledge improvement in areas of water and sanitation, food and nutrition, and disaster preparedness immediately after the Health-EDRM education interventions. Temporal stability of knowledge retention was observed in household hygiene and waste management and smoking beliefs in 2018, 7 years after the interventions. Other important findings include knowledge uptake pattern differences of oral rehydration solution (ORS) between earthquake-prone and flood-prone communities. Usage of Internet and mobile technology for accessing disaster-related information was found to be independent of gender and income. Overall, this study demonstrated the knowledge improvement through Health-EDRM education interventions in a remote rural community. Promoting behavioral changes through interventions to raise awareness has the potential to reduce health risks in transitional post-disaster settings. Future programs should aim to identify evidence-based practices and explore how technology can support Health-EDRM education among vulnerable subgroups.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

China’s transition from an agrarian to an urbanized society has strong reverberations in rural populations. The country’s rapid economic, social, and infrastructural development in recent decades has notably improved the living standard of most rural communities (NDRC 2013; Hong 2016; National Bureau of Statistics of China 2017). But economic development, rural–urban migration, and income disparity have also resulted in the widespread diffusion of unhealthy lifestyle practices, altered dietary habits, and the uptake of tobacco use (Wang 2005; Zhai et al. 2014). Prevalence of chronic diseases, such as hypertension (increasing from 18.6 to 23.5% in rural areas, 2002–2012), is steadily rising (NHFPC 2016). Previous studies have indicated that low-income rural villages in remote areas have difficulty in accessing public emergency services and are particularly vulnerable to disasters (Chan 2013; Du et al. 2016). Transitional villages, defined as rural villages in the process of urbanization, represent an important living context with respect to China’s residents’ future health trajectory. Health needs in rural transitional communities need to be examined and health education should be tailored and evaluated to raise awareness, promote habit-changing behavior, and minimize unfavorable health outcomes.

Although a significant proportion of China’s population living in disaster-prone areas are rural ethnic minority groups (Chan 2018), previous intervention studies conducted in rural areas, except for Chan et al. (2017a), have mainly focused on non-ethnic minority communities, particularly children (Xu et al. 2000), disaster victims (Wang et al. 2000), local villagers and students (Tian et al. 2007), rural residents (Huang et al. 2011), and women (Jin et al. 2007; Long et al. 2010). Health promotion and disaster risk reduction (DRR) research that focuses on ethnic minority groups in rural transitional community is lacking (Chan 2018; Wang 2002).

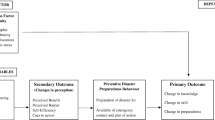

Health-EDRM is a newly emerged academic field that encompasses emergency and disaster medicine, DRR, humanitarian response, community health resilience, and health systems resilience, and is also the intersection of health and disaster risk reduction (Chan and Murray 2017; Lo et al. 2017). To decrease the impact of disasters on people, Health-EDRM argues that disaster vulnerability should be reduced along with raising awareness and supporting preparedness through emergency and disaster risk management education interventions (WHO 2013). Disaster preparedness encompasses the activities that need to be pursued in advance of a disaster to ensure an effective response to the impact of hazards (Chan 2017). Previous studies have emphasized the importance of disaster preparedness (Wu et al. 2018; Xu et al. 2018), particularly of local communities, as the overall level of household preparedness is generally low (Ning et al. 2013; Han et al. 2017b; Wu et al. 2018). Although considerable official efforts and resources have been invested in China with the aim of increasing disaster preparedness, multilevel efforts will be important to effectively address the response and health needs of transitional communities (Chan 2013, 2018).

Various health promotion strategies such as hygiene education, healthy lifestyle improvement, and environmental protection may address the health concerns of rural communities (Howard et al. 2002). A grassroots approach to emergency disaster preparedness for resource-poor rural communities is of particular importance, as timely external assistance is often absent in remote regions. Nonstructural approaches, such as warnings and household preparedness—for example, disaster kits (Pickering et al. 2018)—may be the most cost-effective means of reducing loss of life (Kelman 2013). Oral rehydration solution (ORS) may prevent or treat diarrheal-related dehydration, irrespective of the cause or age group affected (WHO 2006), and is a useful self-help solution in post-disaster settings (CDC 2014; Moghazy et al. 2016). Making ORS available at household and community levels contributes to reducing diarrheal-related mortality by 93% (WHO 2008; Munos et al. 2010). But there is limited evidence of Health-EDRM research in health promotion and disaster risk reduction available in the literature.

This study examined the temporal stability of health promotion and disaster risk education in a transitional village in China. A Health-EDRM health education program was implemented between 2009 and 2018 in Ma’an Qiao Village, Sichuan Province, China. This community is an earthquake-prone, ethnic minority, transitional village in China. A serial cross-sectional, survey-based study was conducted at various preset time points during the program implementation period. The objectives of this study were to: (1) capture the changes in the observed sociodemographic characteristics of the study population between 2011 and 2018; (2) evaluate the knowledge retention of the 2010/2011 health education intervention in 2018; (3) assess the disaster preparedness awareness of the study population; (4) compare the effectiveness of the 2018 oral rehydration solution intervention in the study population to that in a flood-prone ethnic minority population; and (5) investigate the practices of using technology in disaster preparedness.

1.1 Project Background and Study Context: Ma’an Qiao Village in Sichuan Province

In 2009 the Ethnic Minority Health Project (EMHP) was established in China, with a core mission to develop and evaluate effective interventions of bottom-up health and emergency and disaster risk management (Health-EDRM) for vulnerable populations in remote areas of the country. The 14 project sites, distributed across nine provinces, from the Yangtze River to the Ancient Silk Road, were selected based on four selection criteria—geographical remoteness, a large ethnic minority population, economic vulnerability (living on under USD 1.25/person per day), and disaster vulnerability (Chan et al. 2017a; Chan 2018). One of the first EMHP project sites—Ma’an Qiao Village—is located in the Jinsha River area of Xin’an Township, Huili County, Sichuan Province, China (Fig. 1). Populated mainly by people of Dai and Yi ethnicity, the village has over 1200 residents living in over 300 households that are distributed among seven subgroups.

On 30 August 2008, a 6.1 magnitude earthquake in nearby Panzhihua City led to almost complete destruction of the Ma’an Qiao Village’s infrastructure. Overall, the earthquake caused around 40 deaths, affected over 941,000 people, and destroyed many buildings in Sichuan and Yunnan Provinces (IFRC 2008; Yang 2010). After the 2008 earthquake, a 3-year project—jointly supported by the Chinese government, the Wu Zhi Qiao (Bridge to China) Charitable Foundation, and the Collaborating Centre for Oxford University and CUHK for Disaster and Medical Humanitarian Response (CCOUC), The Chinese University of Hong Kong—was established to provide Health-EDRM interventions between 2009 and 2011. Promotion and intervention programs were adapted for the local context according to the Healthy Village guidelines (Howard et al. 2002), including topics of water and sanitation, nutrition, hygiene, vector-borne diseases, waste management, and the importance of disaster kit preparation. In January 2018, a conjoint evaluation project team returned to complete a reevaluation program. Since the project establishment in 2009, Ma’an Qiao Village has experienced increased access to electricity, appliances, and Internet technology. By 2018, approximately a third of the village population had become migrant workers employed in nearby townships and cities.

Health-EDRM needs assessments were conducted during the initial visit in 2009. During the first intervention visit in 2010, water and sanitation, smoking, and disaster preparedness interventions were implemented in the community. During the second visit in 2011, food and nutrition, household hygiene, waste management, and disaster preparedness interventions were implemented in the same community. The disaster preparedness interventions focused specifically on preparing a disaster kit and each participant received a disaster kit as a reminder. The disaster kit included life-saving items such as an emergency blanket, flint fire-starter, flashlight, and multi-purpose pocket knife, and instructions for an oral rehydration solution (ORS) recipe were available on the bag itself. During the 2010 and 2011 visits, pre-intervention and post-intervention surveys (immediately after the intervention) were collected from the participants. During the project period, the collaborating infrastructure team supported the reconstruction of housing, community buildings, and bridges to enhance local capacity and social development. During the 7-year follow-up visit in 2018, a health education intervention on ORS was provided to the villagers. A pre-intervention survey was conducted 1 day before the intervention and a post-intervention survey was administered immediately after to assess the knowledge of ORS among participants. In the post-intervention questionnaire, knowledge retention from the 2010/2011 health promotion and disaster risk reduction education program, and technology-related practices were also assessed.

2 Methodology

This was a 7-year follow-up serial cross-sectional survey-based study of a Health-EDRM education intervention program (2009–2018).

2.1 Sampling

Program participants in the interventions in 2010, 2011, and 2018, were adult household representatives (≥ 18 years in age) who were invited to attend interventions through promotional activities such as household visits, leaflet distribution, and publicly displayed posters. As of 2018, Ma’an Qiao Village had 316 registered households. In 2010 and 2011, participants were invited to complete pre- and post-intervention surveys on-site at the health interventions. Respondents of the 2018 pre-intervention survey were recruited through household visits the day before the intervention using a convenience sampling approach. One subject would be invited from each of the households of the community. Households with more than one family member who participated in the education activities would nominate a study qualified subject over 18 years of age to join the study. Every adult participant on-site at the 2018 intervention was invited for the post-intervention survey. Among all the households, 29 household representatives responded to the pre-intervention survey (9.2% of the sampling frame), whereas 71 household representatives responded to the post-intervention questionnaire (58.6% females; 22.5% of the sampling frame).

2.2 Evaluation Tool

During the January 2018 visit, a 64-item, self-administered questionnaire evaluated the combined 2010/2011 education intervention topics and was comprised of the following sections: (1) sociodemographic characteristics; (2) previous intervention participation; (3) household environmental assessment, on areas such as household hygiene, livestock management, and electronic appliances; (4) hand and environmental hygiene; (5) smoking; (6) dietary practices; (7) waste management; (8) disaster preparedness; (9) use of Internet technology for disaster-related information; and (10) knowledge of oral rehydration solution.

Four local dialect translators were recruited to facilitate communication with the program attendees who could not speak Mandarin (approximately 20% based on field observations). Verbal consent was obtained from all study participants prior to administering the questionnaire. For those who could not complete the questionnaire due to literacy problems, the questionnaire was administered face-to-face by field researchers and local translators.

2.3 Data Management and Analyses

The data collected were double entered and cleaned by trained research staff. Descriptive analyses were conducted and a χ2 test was used to analyze group differences and compare the village data with the provincial-level data. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 21.0 (IBM Corporation 2012). Ethics approval was obtained from the Joint Chinese University of Hong Kong—New Territories East Cluster Clinical Research Ethics Committee (ref no. 2016.334).

3 Results

Our results are presented in the following five sections.

3.1 Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Sample Population and Longitudinal Changes

The final study sample in the 2018 evaluation was comprised of 71 household representatives. The sociodemographic characteristics of the 2011 and 2018 village study samples, as well as the Sichuan provincial census data for 2010/11 and 2014/15 are shown in Table 1. When compared with the general Sichuan Province population, the participants were more likely to be engaged in the agricultural sector. There was a higher proportion of females, older people, non-Han ethnic minorities, lower education levels, and lower income levels.

When comparing the 2011 and 2018 study samples, Ma’an Qiao Village showed a significant increase in educational attainment (p = 0.04) and a four-fold increase in income per capita (p < 0.01) across the years. Those who self-reported a good health status also increased from 39.5 to 61.8%. By 2018, the average household had 4.2 members and an annual income of USD 9159 (RMB 58,123 Yuan), equivalent to an annual average income of USD 2841 (RMB 18,026 Yuan) per person. Of the 2018 households, 33.3% had children under the age of five and 56.9% reported living with elderly person(s) (> 60 years of age). Among the participants in the 2018 study, 66.2% had previously attended one of our 2010 or 2011 health education interventions.

3.2 Knowledge Retention of the 2010/2011 Health Education Interventions in 2018

Data on various health and disaster risk beliefs and practices collected in the 2018 questionnaire, and the results of similar questions asked during the 2010/2011 visits were compared and are shown in Table 2.

Knowledge retention 7 years after the interventions was found in many areas of health beliefs and practices, especially in personal/household hygiene and waste management. Previous beliefs that livestock can roam freely in the house and that burning different wastes together is safe decreased dramatically right after the 2011 intervention (from 62.0 to 24.7%, and from 67.7 to 47.9%, respectively). These patterns maintained similar levels when assessed in 2018. At the same time, 92.9% of the respondents in 2018 believed that free-roaming livestock in the house affected their health, a 4.5% increase from 2011.

The improved beliefs and practices of water and sanitation, food and nutrition, and smoking also demonstrated evidence of knowledge retention in 2018. Over 97% of the respondents maintained the belief of hand washing before eating and after using the toilet, and the need to clear openly defecated feces. Improvements of 9.1%, 6.4% and 5.7%, respectively, were found when compared with the baseline data in 2010. Over 90% believed that drinking alcohol and smoking are harmful to health after the interventions. The belief that smoking causes lung cancer increased from 64.0% at the 2010 baseline to 94.7% right after the 2010 intervention. This was maintained at 94.3% in the 2018 evaluation.

However, the intervention effect of other health promotion beliefs and practices were found to deteriorate with time. By 2018, beliefs that preserved meat contains more salt than fresh meat and that consuming less salt reduces the risk of hypertension had declined from 94.9% and 95.7% in 2011 to 85.7% and 81.4% in 2018, respectively. Respondents also lost some confidence in coping with disasters and the intention to prepare a disaster kit decreased across the years. Only 85.3% of the respondents felt confident about coping with disasters, even lower than the 2010/2011 baseline of 89.0%. At the same time, by 2018, only two-thirds of the respondents reported they would prepare a disaster kit, dropping from 93.2% in the 2010/2011 post-intervention survey.

3.3 Seven-Year Post-Intervention Disaster Preparedness Retention in 2018

A disaster preparedness intervention was conducted in Ma’an Qiao Village in 2010/2011. During the 2018 follow-up visit, the evaluation survey assessed the villagers’ current beliefs in disaster preparedness. In this 2018 evaluation study, 94.3% of the respondents agreed it was important to have disaster preparedness. Almost all respondents knew a key evacuation strategy—for example, going to higher grounds in the event of a flood, or to avoid steep slopes and river banks in an earthquake. About 85% of the respondents reported confidence in coping with a disaster, and 88.6% thought a disaster preparedness kit was important. However, only 68.6% planned to prepare such a kit. Variations were found in the knowledge of items to be included in a disaster preparedness kit from four major groups: (1) health and hygiene; (2) disaster response and household; (3) information and documentation; and (4) personal (Fig. 2). The three most commonly reported preparedness items included a flashlight (65.5%), first aid equipment (61.8%), and common use medications (50.9%). Items for immediate disaster relief response were more likely to be remembered, while items for disaster recovery, such as information/documentation items, were less mentioned. For instance, although a family photo and a copy of an individual’s identity card is pertinent for personal identification, search and rescue, and communication in disasters, only 23.6% had intentions of packing those identification documents, and merely 5.5% reported awareness of the significance of these documents.

Knowledge retention of items to be included in a disaster preparedness kit in earthquake-prone Ma’an Qiao Village, Sichuan in 2018*. Note The surveyed items were developed according to the five core components that support human survival and maintain health in disasters and emergencies (The Sphere Project 2011; Chan 2018). For the purpose of this study, items were regrouped to demonstrate the current knowledge gaps of disaster preparedness kit preparation in the studied community. *A total of 55 respondents were included in this analysis from the 71 valid study samples, due to missing data

3.4 Effectiveness of the 2018 Intervention on Oral Rehydration Solution (ORS)

During the 2018 pre-intervention survey, none of the respondents indicated knowledge of ORS preparation, although 72.4% of the respondents had the general health knowledge and awareness that diarrhea could cause dehydration and 82.8% knew that dehydration could lead to death (Fig. 3). The post-intervention results indicated improvement in the awareness, composition, and knowledge of preparing ORS. Of the individuals who attended the intervention, 39.4% said they knew how to prepare ORS, although only 11.3% reported the correct amount of each ingredient needed in ORS. Improvement in understanding the relationship between diarrhea and dehydration (89.6%) and the potential fatal impact of unmanaged dehydration (89.7%) were also observed.

Comparison of 2018 post-intervention ORS knowledge between Ma’an Qiao Village and Hongyan Village, Sichuan. Note Hongyan Village data from Chan et al. (2017a)

To further understand if ORS knowledge uptake might vary according to disaster risk subtypes, we compared the self-reported knowledge level of ORS preparation between Ma’an Qiao Village, an earthquake-prone village, to Hongyan Village, a flood-prone village (Chan et al. 2017a) (Fig. 3). Hongyan Village is located in the same Autonomous Prefecture as Ma’an Qiao Village, and had the same intervention program design and intervention evaluation method administered. Despite the similarities of intervention design and geographic locations in the two communities, there were major differences in the reported knowledge after the intervention. The Ma’an Qiao community seemed to report a better understanding of the health consequences relating to diarrhea and dehydration compared to the respondents in Hongyan Village (Fig. 3). But knowledge of ORS composition and the ability to prepare ORS was reported by almost twice as many people in flood-prone Hongyan Village than in earthquake-prone Ma’an Qiao Village, although the percentage of respondents in Hongyan Village that reported feeling a difficulty in preparing the ORS had increased somewhat after the intervention.

3.5 Use of Technology in Disaster Preparedness

Of the responding households, 70.4% reported having access to home-based Internet and spending an average of 1.36 h per day on the Internet in 2018. They also reported having an average of 2.6 mobile phones per household, which was in stark contrast to 2011 when only 20% of the village households had any form of communication devices. Most respondents use the Internet to access the news or community-related information (69.8%) and to search for practical information (49.1%).

Of all the respondents who answered the technology section of the questionnaire, 37.3% (n = 22 out of 59) indicated they currently use the Internet to obtain disaster-related information and 62.5% (n = 40 out of 64) would use a disaster-related mobile app, if made available. Gender and income were not significantly associated with current use of the Internet for disaster information or the intention to use disaster-related mobile apps. But the unadjusted analyses revealed that those over the age of 45 and those with primary education or less were significantly less likely to use the Internet for disaster information [Odds Ratio (OR) 0.25, 95% Confidence Interval (CI): 0.08–0.77, p = 0.014, and OR 0.13, 95% CI: 0.04–0.45, p < 0.001, respectively]. The corresponding age and education levels were also significant for the intention to use disaster mobile apps (OR 0.22, 95% CI: 0.07–0.68, p = 0.007, and OR 0.10, 95% CI: 0.02–0.49, p < 0.001, respectively).

4 Discussion

The main study findings show that Health-EDRM education interventions with an emphasis on healthy lifestyles can empower remote rural communities for building resilience and reducing health risks associated with disasters and health emergencies. Reducing disaster risks and increasing disaster preparedness play key roles in reducing disaster vulnerability, especially activities that integrate public health and disaster management (Keim 2008; Chan 2018). The Health-EDRM interventions assessed in this study had not only improved the immediate knowledge of the participants (2010/2011), but temporal stability was also observed 7 years later (2018) in this remote ethnic minority-based, transitional rural community. Awareness of issues and practices in water and sanitation, personal/household hygiene, smoking, alcohol, and waste management had been maintained, compared to the levels reported after the 2010/2011 intervention 7 years before. It is important to emphasize that no other attempts or implementations of similar health interventions or related programs were reported in the studied community between these intervention years. Yet, the observed changes and the uptake of health behaviors may also have resulted from improved socioeconomic conditions, access to media and Internet technologies, and knowledge transfer from transitional migrant populations. Future Health-EDRM studies should attempt to disentangle how environmental context may affect intervention effects.

The intention to prepare a disaster preparedness kit had decreased over time, despite residing in an earthquake-prone community, where the last major earthquake in 2008 had destroyed all residential houses. This may suggest that the local villagers have inadequate disaster awareness and preparedness, which is consistent with findings of Du et al. (2016). Furthermore, in Chinese culture, disaster response has been conceptualized as a government-initiated and organized activity (Xu and Lu 2013), and the literature has shown that the perception of effective government support may inadvertently diminish individual preparedness (Han et al. 2017a). Bottom-up approaches to disaster preparedness, such as the active inclusion of the disaster kit, and reinforcement with repeated educational efforts might be worthwhile to enhance both the importance of self-efficacy and self-help responses in the case of an emergency. The findings indicated that there were major inconsistencies about which items should be placed in a disaster kit. Particularly, the idea to include information and documentation items (such as family photos and identity cards) was lacking. The absence of personal identification may pose extra barriers for disaster-affected communities if entitlement and access to official relief materials and resources are linked to verifying identity. With the advancement of technology and cameras available on most mobile phones, more can be done to explore the facilitation of these items.

Throughout this 7-year study period, we also observed the transformation of a remote underdeveloped village into a transitional village. One major avenue of socioeconomic development in these transitional rural communities is the mass migration of rural workers to urban areas (State Council 2006; Chan 2010; Lu and Xia 2016). The results of this study show an improvement in the villagers’ general socioeconomic conditions between 2011 and 2018, particularly with respect to health status, education, and income levels. However, despite these improvements and the self-reported health protective behaviors, major misconceptions on waste management have lingered as a predominant attitude in the community. Around half of the respondents in 2018 still burned plastics and different types of wastes together. Such behaviors threaten human health and the environment through releasing toxic gases into the atmosphere (Verma et al. 2016). As rising affluence contributes to increased waste generation, and plastics are one of the fastest growing waste streams in China (World Bank 2005), future programs should consider dispelling these key misconceptions in their community health education efforts.

Limited published literature has compared whether disaster preparedness activities will vary according to different disaster subtypes in communities. The EMHP team had published a previous study regarding the Health-EDRM program results of the project conducted in flood-prone Hongyan Village (Chan et al. 2017a). While Ma’an Qiao Village had prior regular reports of diarrhea outbreaks (CCOUC 2009), the study findings from this village indicate that this earthquake-prone community had a different uptake pattern of ORS knowledge immediately after the intervention when compared with the flood-prone Hongyan Village. Despite implementing similar health and emergency DRR programs in both disaster-prone communities (Chan 2018), our results show that the flood-prone residents were 1.60 times more likely to remember ORS preparation and composition details compared with the earthquake-prone community after the intervention. This pattern may be due to a higher risk of diarrheal diseases and occurrences (Chan 2017; Chan et al. 2017a) in flood-prone communities, and thus greater interest in the retention of related knowledge when compared with earthquake-prone communities. These findings highlight the importance of developing bottom-up disaster resilience programs according to the actual health risks and beliefs associated with the targeted communities, their respective disaster subtypes, post-disaster experiences, and perceived health needs.

Finally, information and communication technology is receiving increased attention for its importance in protecting the well-being of communities in extreme events (Laaidi et al. 2013; Chan et al. 2017b). Our findings indicate that technology uptake and the intention to use technology to access disaster information were not associated with gender and income, showing that poverty status may not be a main hindrance to the access of technology or an indicator of willingness-to-use. Instead, those who are younger and more educated have a greater eagerness to seek disaster-related information online. These findings on disaster information seeking were partially consistent with Wu et al. (2018), who also found the same gender and age effects. However, while we focused only on rural areas, Wu et al. (2018) sampled both urban and rural residents at the national level, leading to differing results in education and income effects. Research needs to address the differences between the effectiveness of face-to-face and technology-supported interventions, provide evidence-based results to bridge technology literacy for specific vulnerable subgroups, identify individual- and household-level risk perceptions, and assess how users might choose information sources and knowledge platforms.

A number of research limitations are recognized. First and foremost, a community randomized control trial might be a better study methodology to examine a health education intervention’s effectiveness. Yet, the original field program design, funding availability, and implementation mandates have rendered such a trial design infeasible. Nevertheless, as a 7-year follow-up study and health intervention, the findings of this project represent the actual patterns of change and knowledge retention over the project period. Secondly, this study was a single small village-based study with small sample sizes. Despite its socioeconomic development, the intra-community variation was relatively small in this specific community due to its remoteness. Although the generalizability to other remote ethnic minority communities remains to be examined by large-scale studies, our findings will at least offer a pilot study to understand the health education effects, uptake patterns, and knowledge retention of the Dai and Yi ethnic minorities in transitional communities. In addition, our study tool, although validated in other communities (Chan et al. 2014; Chan et al. 2017a; Chan 2018), is composed of proxy measures that may present limitations in directly reflecting actual circumstances. For example, the question on whether the respondent would prepare a disaster kit was used as a proxy measure for disaster preparedness. It is possible that a respondent had prepared for disasters in other ways instead of preparing a disaster kit. Culture and language barriers remain a major challenge despite the team’s accumulation of over 9 years of working experience in this rural Chinese ethnic minority community. The facilitation of village leaders, language translators, and the enormous support of the villagers have helped to minimize the problem.

Enhancing disaster preparedness is one of the priorities highlighted in the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030 (UNISDR 2015). By focusing on the health risks of the vulnerable population, this EMHP project provided health education for disaster risk reduction in rural China. The study results show the effectiveness of the project in enhancing disaster risk reduction literacy and knowledge retention in the studied ethnic minority community. In addition, this project was found effective in increasing the awareness of personal/household hygiene and other health lifestyles among the residents of the study community, which matches Sustainable Development Goal 3 to “ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages” (UN 2015, p. 14).

5 Conclusion

Knowledge improvement was observed in the areas of water and sanitation, food and nutrition, disaster preparedness, household hygiene and waste management, and smoking beliefs after the Health-EDRM education immediately after the interventions. In particular, knowledge retention 7 years after the interventions was observed in household hygiene, waste management, and smoking beliefs. Knowledge uptake pattern differences in ORS training were observed between an earthquake-prone and a flood-prone community. This finding highlights the importance of designing interventions according to each community’s health risks. The willingness to use disaster-related mobile applications, particularly among the younger and more educated villagers, can help direct future developments. The health risks and needs of rural communities will evolve with the rapidly changing levels of education, income, and access to processed foods, along with other aspects of modernization. Future health promotion and education programs should aim to strengthen heath education for groups that demonstrate suboptimal uptake, focus on utilizing technology (for example, mobile apps/Internet) to disseminate disaster-related information, and further examine effective approaches to build bottom-up Health-EDRM programs in transitional villages for the decades to come.

References

CCOUC (Collaborating Centre for Oxford University and CUHK for Disaster and Medical Humanitarian Response). 2009. CCOUC center report: Health needs assessment post 2008 Panzhihua earthquake. Hong Kong: CCOUC.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2014. Guidelines for the management of acute diarrhea after a disaster. https://www.cdc.gov/disasters/disease/diarrheaguidelines.html. Accessed 14 Feb 2018.

Chan, E.Y.Y. 2013. Bottom-up disaster resilience. Nature Geoscience 6(5): 327–328.

Chan, E.Y.Y. 2017. Public health humanitarian responses to natural disasters. London: Routledge.

Chan, E.Y.Y. 2018. Building bottom-up health and disaster risk reduction programmes. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chan, E.Y.Y., and V. Murray. 2017. What are the health research needs for the Sendai Framework? The Lancet 390(10106): e35–e36.

Chan, E.Y.Y., C. Guo, P.Y. Lee, S.D. Liu, and C.K.M. Mark. 2017. Health Emergency and Disaster Risk Management (Health-EDRM) in remote ethnic minority areas of rural China: The case of a flood-prone village in Sichuan. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science 8(2): 156–163.

Chan, E.Y.Y., Z. Huang, C.K.M. Mark, and C. Guo. 2017. Weather information acquisition and health significance during extreme cold weather in a subtropical city: a cross-sectional survey in Hong Kong. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science 8(2): 134–144.

Chan, E.Y.Y., J. H. Kim, C. Lin, E.Y.L. Cheung, and P.P.Y. Lee. 2014. Is previous disaster experience a good predictor for disaster preparedness in extreme poverty households in remote Muslim minority based community in China? Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 16(3): 466–472.

Chan, K.W. 2010. The global financial crisis and migrant workers in China: ‘there is no future as a labourer; returning to the village has no meaning’. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 34(3): 659–677.

Du, F., H. Kobayashi, K. Okazaki, and C. Ochiai. 2016. Research on the disaster coping capability of a historical village in a mountainous area of China: case study in Shangli, Sichuan. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences 218: 118–130.

Google. 2014. Ma’an Qiao Village. https://www.google.com.hk/maps/place/Ma’an+Bridge/@27.0746073,100.1798928,7.5z/data=!4m5!3m4!1s0x36dbd854dd757e87:0xe692c9a2cabe6272!8m2!3d26.137857!4d102.116191?hl=en. Accessed 14 Feb 2018.

Han, Z., X. Lu, E. I. Hörhager, and J. Yan. 2017. The effects of trust in government on earthquake survivors’ risk perception and preparedness in China. Natural Hazards 86(1): 437–452.

Han, Z., H. Wang, Q. Du, and Y. Zeng. 2017. Natural hazards preparedness in Taiwan: A comparison between households with and without disabled members. Health Security 15(6): 575–581.

Hong, Y. 2016. Integrated urban–rural development. In The China path to economic transition and development, ed. Y. Hong, 151–169. Singapore: Springer.

Howard, G., C. Bogh, G. Goldstein, J. Morgan, A. Prüss, R. Shaw, and J. Teuton. 2002. Healthy villages: A guide for communities and community health workers. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/42456/1/9241545534.pdf. Accessed 9 May 2018.

Huang, S., X. Hu, H. Chen, D. Xie, X. Gan, Y. Wu, S. Nie, and J. Wu. 2011. The positive effect of an intervention program on the hypertension knowledge and lifestyles of rural residents over the age of 35 years in an area of China. Hypertension Research 34(4): 503–508.

IBM Corporation. 2012. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 21.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

IFRC (International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies). 2008. Information bulletin—China: Eearthquake in Sichuan and Yunnan. http://www.sinoptic.ch/textes/communiques/2008/20080902_CNeq_Sichuan_Yunnan.pdf. Accessed 15 Feb 2018.

Jin, X., Y. Sun, F. Jiang, J. Ma, C. Morgan, and X. Shen. 2007. “Care for development” intervention in rural China: a prospective follow-up study. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics 28(3): 213–218.

Kahle, D., and H. Wickham. 2013. ggmap: spatial visualization with ggplot2. The R Journal 5(1): 144–161.

Keim, M. E. 2008. Building human resilience: The role of public health preparedness and response as an adaptation to climate change. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 35(5): 508–516.

Kelman, I. 2013. Disaster mitigation is cost effective. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Laaidi, K., A. Economopoulou, V. Wagner, M. Pascal, P. Empereur-Bissonnet, A. Verrier, and P. Beaudeau. 2013. Cold spells and health: prevention and warning. Public Health 127(5): 492–499.

Lo, S.T.T., E.Y.Y. Chan, G.K.W. Chan, V. Murray, A. Ardalan, and J. Abrahams. 2017. Health Emergency and Disaster Management (H-EDRM): developing the research field within the Sendai Framework paradigm. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science 8(2): 145–149.

Long, Q., T. Zhang, L. Xu, S. Tang, and E. Hemminki. 2010. Utilisation of maternal health care in western rural China under a new rural health insurance system (New Co-operative Medical System). Tropical Medicine & International Health 15(10): 1210–1217.

Lu, M., and Y. Xia. 2016. Migration in the People’s Republic of China. ADBI working paper 593. Tokyo: Asian Development Bank Institute.

Moghazy, A.M., O.A. Adly, M.A. Elbadawy, and R.E. Hashem. 2016. Evaluation of who [sic; WHO] oral rehydration solution (ORS) and salt tablets in resuscitating adult patients with burns covering more than 15% of total body surface area (TBSA). Annals of Burns and Fire Disasters 29(1): 43–47.

Munos, M.K., C.L.F. Walker, and R.E. Black. 2010. The effect of oral rehydration solution and recommended home fluids on diarrhoea mortality. International Journal of Epidemiology 39(Suppl 1): i75–i87.

National Bureau of Statistics of China. 2010. 2010 population census. http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/pcsj/rkpc/6rp/indexch.htm. Accessed 14 Feb 2018 (in Chinese).

National Bureau of Statistics of China. 2016. China statistical yearbook 2016. http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/ndsj/2016/indexch.htm. Accessed 14 Feb 2018 (in Chinese).

National Bureau of Statistics of China. 2017. China statistical yearbook 2017. http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/ndsj/2017/indexch.htm. Accessed 14 Feb 2018 (in Chinese).

NDRC (National Development and Reform Commission). 2013. Rural infrastructure development report (2013). http://njs.ndrc.gov.cn/tzzn/201504/W020150401347572595490.doc. Accessed 14 Feb 2018 (in Chinese).

NHFPC (National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People’s Republic of China). 2016. China health and family planning statistical yearbook 2016. Beijing: Peking Union Medical College Press (in Chinese).

Ning, Y., M.X. Tao, J.F. Hu, Y.B. Li, Y.L. Cheng, G. Zhang, T. Hu, and L. Li, et al. 2013. Status of household disaster preparedness and affecting factors among the general public of four counties in Shaanxi. Chinese Journal of Preventive Medicine 47(4): 347–351 (in Chinese).

Pickering, C.J., T.L. O’Sullivan, A. Morris, C. Mark, D. McQuirk, E.Y. Chan, E. Guy, G.K. Chan, et al. 2018. The promotion of ‘Grab Bags’ as a disaster risk reduction strategy. PLoS Currents. https://doi.org/10.1371/currents.dis.223ac4322834aa0bb0d6824ee424e7f8.

State Council. 2006. Several opinions of the state council on settling issues on rural migrant workers. http://www.gov.cn/gongbao/content/2006/content_244909.htm. Accessed 14 Feb 2018 (in Chinese).

Statistical Bureau of Sichuan. 2012. Sichuan statistical yearbook 2012. http://www.sc.stats.gov.cn/tjcbw/tjnj/2012/index.htm. Accessed 14 Feb 2018 (in Chinese).

Statistical Bureau of Sichuan. 2015. Sichuan statistical yearbook 2015. http://www.sc.stats.gov.cn/tjcbw/tjnj/2015/index.htm. Accessed 14 Feb 2018 (in Chinese).

Sichuan Center for Disease Control and Prevention. 2018. Population health status and key diseases in Sichuan province 2017. http://www.sccdpc.gov.cn/View.aspx?id=15534. Accessed 14 Feb 2018 (in Chinese).

The Sphere Project. 2011. The Sphere project: humanitarian charter and minimum standards in humanitarian response. http://ocw.jhsph.edu/courses/RefugeeHealthCare/PDFs/SphereProjectHandbook.pdf. Accessed 13 Sept 2018.

Tian, L., S. Tang, W. Cao, K. Zhang, V. Li, and R. Detels. 2007. Evaluation of a web-based intervention for improving HIV/AIDS knowledge in rural Yunnan, China. Aids 21(Suppl 8): S137–S142.

UN (United Nations). 2015. Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015: A/RES/70/1—transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/70/1&Lang=E. Accessed 15 Aug 2018.

UNISDR (United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction). 2015. Sendai framework for disaster risk reduction. https://www.unisdr.org/we/coordinate/sendai-framework. Accessed 15 Aug 2018.

Verma, R., K.S. Vinoda, M. Papireddy, A.N. Gowda. 2016. Toxic pollutants from plastic waste—a review. Procedia Environmental Sciences 35: 701–708.

Wang, H. 2002. Predictors of health promotion lifestyle among three ethnic groups of elderly rural women in Taiwan. Public Health Nursing 16(5): 321–328.

Wang, L. 2005. Comprehensive report, Chinese nutrition and health survey in 2002. Beijing: People’s Medical Publishing House (in Chinese).

Wang, X., L. Gao, H. Zhang, C. Zhao, Y. Shen, and N. Shinfuku. 2000. Post-earthquake quality of life and psychological well-being: longitudinal evaluation in a rural community sample in northern China. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 54(4): 427–433.

WHO (World Health Organization). 2006. Oral rehydration salts: production of the new ORS. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/69227/WHO_FCH_CAH_06.1.pdf?sequence=1. Accessed 14 Feb 2018.

WHO (World Health Organization). 2008. WHO position paper on oral rehydration salts to reduce mortality from cholera. http://www.who.int/cholera/technical/ORSRecommendationsForUseAtHomeDec2008.pdf. Accessed 14 Feb 2018.

WHO (World Health Organization). 2013. Emergency risk management for health overview. http://www.who.int/hac/techguidance/preparedness/risk_management_overview_17may2013.pdf. Accessed 14 Feb 2018.

World Bank. 2005. Waste management in China: issues and recommendations. Urban development working papers 9. http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTEAPREGTOPURBDEV/Resources/China-Waste-Management1.pdf. Accessed 14 Feb 2018.

Wu, G., Z. Han, W. Xu, and Y. Gong. 2018. Mapping individuals’ earthquake preparedness in China. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences 18(5): 1315–1325.

Xu, D., L. Peng, S. Liu, and X. Wang. 2018. Influences of risk perception and sense of place on landslide disaster preparedness in southwestern China. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science 9(2): 1–14.

Xu, J., and Y. Lu. 2013. A comparative study on the national counterpart aid model for post-disaster recovery and reconstruction: 2008 Wenchuan earthquake as a case. Disaster Prevention and Management 22(1): 75–93.

Xu, L.S., B.J. Pan, J.X. Lin, L.P. Chen, S.H. Yu, and J. Jack. 2000. Creating health-promoting schools in rural China: a project started from deworming. Health Promotion International 15(3): 197–206.

Yang, D. 2010. The China environment yearbook, volume 4 tragedy and hope—from the Sichuan earthquake to the olympics. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill.

Zhai, F.Y., S.F. Du, Z.H. Wang, J.G. Zhang, W.W. Du, and B.M. Popkin. 2014. Dynamics of the Chinese diet and the role of urbanicity, 1991–2011. Obesity Reviews 15(S1): 16–26.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the 2018 EMHP-CCOUC team for their help and facilitation in the data collection process. Members of the team included Dr. Tony K.C. Yung, Dr. Joyce M.S. Leung, Eric S.K. Yau, Kelvin W.K. Ling, Cherry L.Y. Lin, Terry Wong, Zhuqing Chang, Gloria K.W. Chan, Asta Man, Evan Shang, Ada Fong, Regan Tam, Kaffee Mok, Sarah Chan, Dr. Kevin Hung, Dr. Eliza Cheung, Poyi Lee, Professor Edward Ng, Dr. Qifu Dai, Dr. Wan Li, Jie Ma, and all the CCOUC field volunteers and student teams across the different stages of the Jinsha River project development and the various data collection efforts from 2009 to 2018. This study also builds on the work of a number of previous research theses and reports written by Hale Ho, Dr. Cecilia Choi, John Lee, and Ada Fong. Special acknowledgment is expressed to the Wu Zhi Qiao Foundation for all their support and facilitation in establishing this program. Most important of all, the authors and the program teams are grateful to all the Ma’an Qiao villagers who supported and participated in the program and its various evaluation attempts throughout the years. This study was funded by the CCOUC Disaster and Medical Research Fund, the School of Public Health and Primary Care Research Fund, the Wu Zhi Qiao Charitable Foundation, the Lee Hysan Foundation, I·CARE, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, and Jockey Club Disaster Preparedness and Response Institute.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Chan, E.Y.Y., Ho, J.Ye., Huang, Z. et al. Long-Term and Immediate Impacts of Health Emergency and Disaster Risk Management (Health-EDRM) Education Interventions in a Rural Chinese Earthquake-Prone Transitional Village. Int J Disaster Risk Sci 9, 319–330 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13753-018-0186-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13753-018-0186-5