Abstract

There is a growing body of research documenting the impact of traumatic stress on child development, which has resulted in a call to action for trauma-informed practices as a priority, yet implementation within schools and training for educators is lacking (American Academy of Physicians, https://www.aap.org/en-us/Documents/ttb_aces_consequences.pdf, 2014). Understanding teachers’ perceptions regarding current levels of knowledge, self-efficacy, and trauma-informed training can help guide future professional development experiences for both pre-service and practising teachers. This study investigated the knowledge, self-efficacy, and training of trauma-informed practices as self-reported by primary educators, serving in grades kindergarten through third-grade, within two regions of Tennessee and Virginia. The Primary Early Childhood Educators Trauma-Informed Care Survey for Knowledge, Confidence, and Relationship Building (PECE-TICKCR) scale was adapted from the TIC-DS scale (Goodwin-Glick in Impact of trauma-informed care professional development of school personnel perceptions of knowledge, disposition, and behaviours towards traumatised students, Graduate College of Bowling Green State University, 2017), validated, and created for the purpose of this study. The sample consisted of 218 primary educators who completed an online survey regarding personal knowledge, self-efficacy, and training experiences of trauma-informed practices. Correlations revealed a statistical significance between the Knowledge of Trauma factor and the Confidence in Providing Trauma-Informed Strategies factor. There was also a statistical significance between the Knowledge of Trauma factor and the Confidence in Creating Supportive relationships factor and between the Confidence in Providing Trauma-Informed Strategies factor and the Confidence in Creating Supportive Relationships factor. The findings indicated that teachers need more knowledge regarding community resources for families and students but feel confident in providing supportive relationships. Teachers also are interested in more training events related to strategies to use when working with students exposed to trauma. Implications for teacher preparation programs and professional development training for practising teachers is discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Childhood trauma, which includes exposure to violence and maltreatment, is known to have a negative impact on children’s development and well-being. In the United States, more than two-thirds of children reported at least one traumatic event by age 16 (SAMSHA, 2014). Research completed by the Center for Disease Control (Merrick et al., 2018) showed that more than 60% of American adults have experienced, as a child, at least one ACE (Adverse Childhood Experience). The CDC also reported (Hillis et al., 2016) over half of all children in the world, one billion children ages 2–17 years, experience violence every year. Childhood exposure to adverse experiences has been negatively associated with outcomes such as student–teacher relationships, self-regulation, (Loomis & Mogro-Wilson, 2019) and academic success (Jimenez et al., 2016).

The potential impact of ACEs on both students and teachers has resulted in research focussed on trauma-informed interventions and trauma-informed care training. The concept “trauma-informed” has been defined as the understanding of the potential effects of trauma on children and adults, recognising and responding to the effects of trauma on children and adults, recognising and responding to the effects of trauma, and trying to avoid re-traumatising individuals (SAMSHA, 2014). Trauma-informed training for childhood educators has been recommended by the US Department of Health and Human Services (2015) as one method for promoting the socioemotional health of young children. The National Association for the Education of Young Children (www.naeyc.org) has initiated numerous discussions about trauma and provided access to professional resources for childhood educators. Head Start programs have recently been encouraged to include trauma-based topics within program activities and trainings (US Department of Health & Human Services, 2020). The trauma-informed movement has also been powered by the recent legislation in the United States, which now describes precise provisions for trauma-informed approaches (Prewitt, 2016), including training and creating trauma-informed schools.

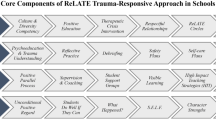

The epidemic of trauma exposure has created a growing movement to provide trauma-informed training and create trauma-informed schools. Trauma-informed care training includes understanding the effects of trauma on children and adults, recognising and responding to the effects of trauma, and making efforts to avoid re-traumatising individuals (SAMSHA, 2014). Rather than interpreting resistant student behaviour as a negative choice the student is making, an educator can utilise the trauma-aware perspective, questioning, and consideration of the underlying potential causes of the behaviour (Stokes & Brunzell, 2019). Research has explored various trauma-informed approaches, which has increasingly pointed to the implementation of multi-tiered programs (Berger, 2019). A systematic literature review identified 13 studies implementing three or more tiers of school-based support, which reported improvements in student academic achievement and behaviour (Berger, 2019).

When teachers lack knowledge, self-efficacy, and training in trauma-informed practices, they may have difficulty managing children’s behaviours resulting from exposure to trauma and managing their own self-care (Alisic et al., 2012). Understanding the current level of knowledge, self-efficacy, and training topics attended and desired by primary education teachers, aids in planning the next steps for preparing teachers to meet the needs of all students within a classroom. As research-based evidence continues to surface regarding the impact of trauma (Bethell et al., 2014), the concept of teaching through a trauma-informed lens has become increasingly important. Looking through a trauma-informed lens means being sensitive to the impact of trauma on others and yourself, understanding and utilising tools to support self and others in regulating during times of stress as well as identifying and supporting the system change needed to reduce re-traumatisation (National Child Traumatic Stress Network, 2020).

The Early Childhood Educators Trauma-Informed Care Survey for Knowledge, Confidence, and Relationship Building (PECE-TICKCR) was designed to gain information from teachers in public-school settings, PreK through third grade, regarding their level of knowledge of trauma-informed practices, their level of self-efficacy in supporting students who have been exposed to trauma, their training experiences with trauma-informed practices, and their interests in further training. Findings from the current study can inform the development of trauma-informed training resources for teachers and initial teacher education programs.

Background

The original Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE) study was designed to investigate the connection between adverse childhood experiences and adult health issues (Felitti et al., 1998). An adverse childhood experience refers to an event that a child can experience which leads to stress and can result in chronic stress responses and trauma (Felitti et al., 1998). The findings indicate “a strong relationship between the number of childhood exposures and the number of health risk factors for leading causes of death in adults” (Felitti et al., 1998, p. 251).

A more recent study (Cronholm et al., 2015) included 1,784 participants who were selected from a more socioeconomically and racially diverse population than the predominantly white, middle/upper class participants from the original ACEs study (Felitti et al., 1998). Of the diverse participants, 73% reported at least one conventional ACE while 50% experienced an expanded form of an ACE (Cronholm et al., 2015).

While the focus of ACE research was health outcomes, the educational impact of living through adverse childhood experiences also needs to be considered. “Because adverse childhood experiences are common, and they have strong long-term associations with adult health risk behaviors, health status, and disease, increased attention to primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention strategies are needed” (Felitti et al., 1998, p. 254). School systems are being impacted as these children come into the educational system. School systems need to be prepared to provide intervention strategies for children who have been exposed to trauma.

Childhood trauma

“The National Child Traumatic Stress Network in the United States reports that up to 40% of students have experienced, or been witness to, traumatic stressors in their short lifetimes” (Brunzell et al., 2015, p. 3). School students effected by trauma may exhibit symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, conduct disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, reactive attachment, disinhibited social engagement, and/or acute stress disorders in the classroom (Blaustein, 2013). Brunzell and associates (2015) found that individuals who had lived through adverse childhood experiences were more likely to have been suspended or expelled, failed a grade, have lower academic achievement, be at significant risk for language delays, and be assigned to special education.

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMSHA, 2014) states trauma results from an event, series of events, or set of circumstances that are experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful or threatening and that has lasting adverse effects on the individual’s functioning and physical, social, emotional, or spiritual well-being (p. 7).

According to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2014), 66.6% of children reported exposure to at least one traumatic event by the age of 16. The Center for Disease Control (2019) reported that one in seven children experienced abuse or neglect. Children exposed to five or more significant adverse experiences in the first 3 years of life face a 76% likelihood of having one or more delays in emotional, brain, or language development (SAMSHA, 2014). Considering the staggering statistics, teachers’ knowledge, self-efficacy, and approach to trauma-informed care in the classroom are critical.

Impact of childhood trauma

Adverse childhood experiences have the potential to result in an array of vulnerabilities across multiple developmental domains of young children, which may begin to appear during childhood and adolescence (Porche et al., 2016). A child’s academic achievements, behaviour, and self-regulation abilities can all be negatively impacted because of exposure to a traumatic experience. A primary education, longitudinal study (Goodman et al., 2012) revealed significant differences in reading, math, and science achievement scores among students exposed to trauma and those without exposure. In all three academic domains, students exposed to trauma scored significantly lower than students with no exposure. A study conducted in 2010 (Milot et al., 2010) examined the relationship between trauma symptoms and behavioural problems among preschool and kindergarten children. The study revealed significant relationships between childhood maltreatment and trauma symptoms, between trauma symptoms and internalising behaviours, and between trauma symptoms and externalising behaviours, all supporting the impact of traumatic experiences (Milot et al., 2010). Adverse childhood experiences can also impact a child’s emotional awareness, understanding, and regulation (Shields et al., 2001), which are skills usually developed through interactions with parental guardians or adults in their lives. Forkey (2019) found that children exposed to trauma exhibit symptoms associated with higher resting heart rates, sleeping irregularities, hypervigilance, hyperactivity, impulsivity, irritability, emotional regulation issues, and attachment issues.

Impact of trauma in the school setting

As students spend a large percentage of their weekdays within the classroom, the school holds the next natural level of responsibility for students displaying the cognitive, behavioural, or academic effects of exposure to a traumatic event. Students exposed to trauma may lack feelings of safety or trust in relationships due to previous unsafe experiences (Courtois & Ford, 2009). Students may misread teachers’ verbal or body language because their previous chronic, unsafe experiences conditioned them to be hypercritical of adult behaviour (Terr, 1991).

Behaviours rooted in trauma often present as outbursts, crying, peer difficulties, or lack of engagement which all have a direct impact on student–teacher and student–student relationships and academic performance (Terr, 1991). Students who have experienced adversities will often require more classroom attention and support, may need learning environment modifications, and can often be more difficult to engage (The Illinois Aces Responses Collaborative, 2017). Toxic stress in the early childhood years can play a direct role in the disparities of educational success and health outcomes of young children (Shonkoff et al., 2012). Communities and educators hold a great responsibility of applying a trauma lens while looking deeply into potential causes of disruptive behaviours.

Trauma training for teachers

Due to the worldwide COVID-19 pandemic, teachers in America and beyond are faced with how best to meet the needs of students who have been exposed to one or more traumatic events. Teachers play an important role in recognising and responding to children who present symptoms of exposure to trauma (Smyth, 2017). Reinke and colleagues (2011) examined 292 elementary and early childhood teachers’ perceptions of the needs, roles, and barriers to supporting children’s mental health in schools. Most teachers (strongly agreed = 31%; agreed = 51%) supported the school’s involvement in addressing students’ mental health issues. When asked to share perceptions of their roles in addressing these issues, teachers viewed themselves as integral. However, when asked if they had the knowledge necessary to meet the mental health needs of their students, only 28% of teachers agreed (strongly agreed = 4%; agreed = 24%). Teachers also indicated their teacher prep programs did not prepare them for meeting the mental health needs of their students (Morton & Berardi, 2018), and because of this deficit were requesting more training, especially specific strategies for working with children exposed to trauma (Onchwari, 2010; Reinke et al., 2011). One university found after including three trauma-based courses for pre-service students, the post-tests revealed an increase in students’ knowledge and skills of trauma-informed care (Canon et al., 2020).

Considering the high percentage of students who have been exposed to trauma and the potential for negative impacts on behavioural, academic, and social outcomes, it is essential to provide educators with opportunities to develop knowledge of trauma, the symptoms of traumatic stress, how to incorporate trauma-informed strategies, and how to create a trauma-informed learning environment for all students. Research reveals that teachers feel a responsibility to help all students but feel unprepared to intervene due to their lack of knowledge about how to meet their mental health needs (Rothi et al., 2008). Some feel educators and school-based mental health providers should consider screening for symptoms of mental health diagnoses, in order to determine the function of behaviours and the appropriate response or strategy (Porche et al., 2016). This type of observation would also require specialised trauma training for educators.

Trauma-informed care dispositions survey (TIC-DS)

A contribution of this paper includes the validation of adapted measures. After an extensive literature search, the TIC-DS (Goodwin-Glick, 2017) was found to be the most useful scale for the purpose of this study. The original TIC-DS scale contained 52 closed-form and one open-ended survey item and is measured on a Likert Scale. The TIC-DS is a valid and reliable instrument. The Cronbach’s alpha for the TIC-DS was found to be .960 on the retrospective pre-test responses and .955 on the post-test responses, which suggests strong internal reliability. The TIC-DS was adapted resulting in the creation of the PECE-TICKCR scale, followed by validation analysis procedures.

Methods

Current study

This study investigated primary early childhood educators' perspectives of knowledge, self-efficacy, training experiences with trauma-informed practices, and their interest for further training regarding trauma-informed practices in PreK through third-grade classrooms. Results of the study were obtained from April to June, 2020, through an online survey. Data were collected from teachers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Four research goals guided this study: (1) What level of knowledge do teachers report having about meeting the needs of students who have experienced trauma; (2) What level of self-efficacy do teachers report having in supporting students who have experienced trauma; (3) What topics of training related to trauma-informed care have teachers received; and (4) What topics of training related to trauma-informed care do teachers desire to better support students in the classroom?

Participants

There were 257 primary early education teachers who consented to participate in the survey. Thirty-one participants consented but did not provide any responses. From the responses, it was determined that eight participants did not meet the inclusion criteria. After eliminations, there were 218 participant responses analysed.

Table 1 reports the demographic characteristics of the participants. Of 218 participants, 91% (n = 200) identified as female and 91% identified as White/Caucasian (n = 199). The most represented age range was 30–40 years (27%, n = 59), followed by 41–50 years (25%, n = 55), then 51–60 years (24%, n = 53). Thirty percent (30%) of participants had 11–20 years of experience as a teacher (n = 66), 28% had more than 20 years (n = 61), 19% were employed as a teacher for 6–10 years (n = 42), and 19% had taught for 5 years or less (n = 43). Teachers held a variety of positions at their schools. The highest number of participants were second-grade teachers (21%, n = 46), followed by first-grade teachers (15%, n = 33), and then special education teachers (15%, n = 32). Characteristics of the school setting were also described in the study. Most participants described their school setting as being suburban (32%, n = 69), followed by rural (29%, n = 64), then urban (20%, n = 43), and then combination of urban/suburban and rural (11%, n = 24). Seventy respondents (32%) reported that 86–100% of their students received free or reduced-price lunches; 46 respondents (21%) reported that 51–75% of students received free or reduced-price lunches; and 32 respondents (15%) reported that 26–50% of students received free or reduced-price lunches.

Instrument development

The researchers determined the specific aims of the project, conducted an extensive review of relevant literature, and determined if existing scales could be used for the current study. After reviewing the reliability and validity, the domains measured, the type of questions, and the length of existing scales, the team decided the scale most useful for the current project was the Trauma-Informed Care Dispositions Survey (TIC-DS) developed by Kelly Goodwin-Glick (2017). After receiving permission from Goodwin-Glick to both use and adapt the survey, the team made wording adaptations while creating the questions for the Knowledge and Self-Efficacy sections of the PECE-TICKCR survey. The knowledge subscale of the TIC-DS was adapted by adding words of specificity to questions to provide consistency across all items (See Table 2). The self-efficacy subscale questions from the TIC-DS were reworded from assessing knowledge to assessing the participant’s ability to act in relation to specific student behaviours (See Table 3). An additional question was also created and added to the PECE-TICKCR, addressing the awareness teachers have of community resources available for children and families who have experienced trauma. Concepts, rather than specific questions, were used from a study conducted by Kassandra Reker (2016) titled Teachers' Perspectives on Supporting Students Experiencing Child Traumatic Stress Final Survey, to guide the development of questions regarding the training experiences of teachers, which are in sections three and four of the PECE-TICKCR survey.

The PECE-TICKCR survey, a self-report questionnaire, was designed and generated online using Qualtrics XM© 2020 and included five sections. The first section asks how knowledgeable one is about various topics related to trauma-informed care in the primary years of childhood. The knowledge section is measured on a Likert Scale ranging from “1” not at all knowledgeable to “5” very knowledgeable. The second section asks how confident the participant is about actions related to trauma-informed care. The confidence section is measured using a Likert Scale ranging from “1” not confident at all to “5” very confident. The third section (3 multiple choice questions) asks about experience working with children who have been traumatised. The fourth section (6 multiple choice questions and two multiple response sets) asks about training received and training in which one might want to participate. The last section (8 multiple choice questions) asks for information about the teachers and work experience. Respondents were also given the option to enter their name and email address into a draw for one of three $100 gift cards. Drawing entry was voluntary, and identifying data were not linked to the responses.

The PECE-TICKCR was pilot tested with a group of approximately 20 practising teachers. They were asked to complete the survey while making anecdotal notes regarding the wording, constructs, and overall feel of the survey. The research team utilised the feedback from the pilot survey to edit and finalise the final survey.

Factor analysis

The factorability of the 24-item PECE-TICKCR was examined. Several well recognised criteria for the factorability of a correlation were used. First, all 24 items correlated at least .3 with at least one other item, suggesting reasonable factorability. Secondly, the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure of sampling adequacy was .94, well above the commonly recommended value of .6, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (p < .05). Given these overall indicators, factor analysis was deemed to be suitable with all 24 items.

A Principal Axis Factor (PAF) with a Varimax (orthogonal) rotation of 24 Likert scale questions from the PECE-TICKCR was conducted on data gathered from 218 participants. PAF was used because the primary purpose was to explore and identify underlying factors of the PECE-TICKR. A three-factor solution, which explained 70% of the variance, was preferred because of the ‘levelling off’ of Eigen values on the scree plot after three factors and the insufficient number of primary loadings on the fourth and subsequent factors. A Varimax orthogonal rotation was used, as the correlations of factors were less than the standard value of .32.

Three factors were identified in the analysis (see Table 2). Ten items loaded under Factor 1, with a range of .36 between the highest loading (.87) and the lowest loading (.51). Factor 1 was labelled “Knowledge of Trauma” as these items related to teachers’ perceptions of their knowledge regarding childhood trauma. Ten items loaded under Factor 2, with a range of .22 between the highest loading (.78) and the lowest loading (.56). Factor 2 was labelled “Confidence in Providing Trauma-Informed Strategies” as these items related to teachers’ perceived ability to manage student behaviours, create a positive learning environment, take steps to support students who have experienced trauma, and assist traumatised students. Four items were loaded under Factor 3, with a range of .15 between the highest loading (.82) and the lowest loading (.67). Factor 3 was labelled “Confidence in Creating Supportive Relationships” as these items related to teachers’ perceived level of self-efficacy in areas related to students’ interactions with each other, students’ interactions with the teacher, and ways to approach relationships.

Reliability test

Internal consistency for each of the scales was examined using Cronbach's alpha. Reliabilities were high for all three factors: Knowledge of Trauma (n = 10, α = .948); Confidence in Providing Trauma-Informed Strategies (n = 10, α = .940); and Confidence in Creating Supportive Relationships (n = 4, α = .865). No substantial increases in alpha for any of the scales could have been achieved by eliminating more items. Overall, these analyses indicated that three distinct factors were underlying teacher responses to the items on the PECE-TICKCR and that these factors were internally consistent.

Data collection

The recruitment process began by sending out invitations for the study to the superintendents of all public-school districts in three regions of two states. Upon receiving their consent to participate, superintendents were asked to provide the names and email addresses of the administrators or principals of schools with PreK through third-grade students. Principals were then contacted and asked to forward the survey link to all teachers at their schools.

Participants accessed the survey using an anonymous hyperlink sent via a recruitment email from the principal of the school at which they were employed. Prior to accessing the survey, teachers were asked to review the IRB-approved informed consent. If consent was not obtained, participants were thanked for their time and the survey closed. A total of 256 survey responses was received.

Data analysis

After cleaning the data, 218 total responses were used for analysis. Survey results were exported from Qualtrics XM© 2020 to Microsoft Excel and IBM Statistical Package for Social Sciences, 27 (SPSS) for analysis. The 13 Knowledge About Trauma items, the 9 Confidence in Providing Trauma-Informed Strategies items, and the 4 Confidence in Creating Supportive Relationships items were totalled individually. Descriptive statistics were used to analyse the data scores from each of the three-factor domains.

Basic descriptive data and frequency statistics were used to analyse training topic events teachers had previously attended, as well as training topic events of which teachers were interested in learning more. If respondents indicated that they had previously attended training on childhood trauma, respondents selected all the training topic events they had attended. Next, teachers were asked if they would be interested in more training on childhood trauma. If they indicated interest, they selected all the events they were interested in, from the same list of training topics.

Results

Descriptive statistics of the three latent factors: Knowledge About Trauma, Confidence in Providing Trauma-Informed Strategies, and Confidence in Creating Supportive Relationships are illustrated in Table 3. Responses of participants range from 1 to 5 on a Likert-style scale with 1 being “not at all knowledgeable” or “not at all confident” and 5 being “very knowledgeable” or “very confident”.

Knowledge about trauma

Participant responses revealed variability in their knowledge across 10 survey items. For four items (knowledge regarding the impact of trauma on students’ social success, the impact of trauma on students’ behaviour, the impact of trauma on students’ ability to learn, and knowledge about how teachers’ behaviour and interactions impact students who have experienced trauma) 70–77% of the participants indicated that they were knowledgeable or very knowledgeable. Five survey items (knowledge about the symptoms traumatised students display, the impact of emotional states on the brain and learning, different types of traumas, the similarity of symptoms for trauma and disability diagnoses, and the steps to take if a student has experienced trauma) had between 50 and 60% of the participants reporting that they were knowledgeable or very knowledgeable. One item, (knowledge of community resources for families and students) revealed 27% of teachers felt knowledgeable or very knowledgeable, and 28% revealed they were not at all knowledgeable or had very little knowledge regarding the topic.

Confidence in providing trauma-informed strategies

The mean response of participants related to Confidence in Providing Trauma-Informed Strategies was slightly higher than those related to Knowledge of Trauma. For three items (confidence in utilising strategies to create a safe environment, being mindful and self-aware of teachers’ interactions with students, and using active listening strategies with students), 74–86% of participants indicated that they were confident or very confident using these strategies. Forty-five to sixty percent of the participants indicated that they were confident or very confident in their abilities to do the following: know the appropriate steps to take if trauma is suspected, take the appropriate next steps, provide support to students who have experienced trauma, de-escalate and manage student behaviours when necessary, interact in ways that have positive impacts on student learning, make behavioural observations of students to identify signs of trauma, and assist students who have been traumatised so they can learn.

Confidence in creating supportive relationships

Teachers were most confident in their ability to support positive relationships with students. All four items related to this factor resulted in high percentages of participants who felt confident or very confident. Survey items related to this factor included being positive with all students (95%), mediating negative student interactions (89%), giving students opportunities to make choices and decisions (90%), and treating all students with dignity and respect at all times (98%).

Training

Table 4 shows the frequencies of training event topics that teachers had attended as well as topics teachers were interested in learning more about. Eighty-four respondents who had attended training indicated the topics of training related to basic knowledge of what childhood trauma is (78%), 79 attended trainings on the impacts of trauma on the behaviour of children (73%), 77 attended training on the causes of childhood trauma (71%), and 75 attended training on how trauma impacts learning during childhood (69%). The training event topics attended the least were on self-care strategies for teachers working with children who have experienced trauma (n = 28, 26%), resources available in the community for families and children dealing with trauma (n = 26, 24%), and how to support parents of children who have experienced trauma (n = 16, 15%).

Out of the sample of 99 teachers who were interested in learning more about childhood trauma, 91% indicated they would like training on effective classroom strategies for supporting students who have experienced trauma (n = 90). This is followed by 68% who were interested in learning about resources and supports that are available and learning about the impacts of trauma on learning and behaviour (n = 67), 66% would like to learn how to support parents of children who have experienced trauma (n = 65), and 60% would like to learn how to determine if a student has experienced trauma (n = 59). Nineteen responded that they would like to learn about what causes childhood trauma (19%), and 16 were interested in training about what is childhood trauma (16%).

Correlations

Pearson correlations revealed statistically significant relationships between the Knowledge of Trauma factor and the Confidence in Providing Trauma-Informed Strategies factor and the (r (217) = .701, p = .01). The effect size is considered large (Cohen, 1988). Pearson correlations also found statistically significant the Knowledge of Trauma factor and the Confidence in Creating Supportive Relationships factor (r (217) = .407, p = .01). This effect size is considered medium (Cohen, 1988). The Confidence in Providing Trauma-Informed Strategies factor and the Confidence in Creating Supportive Relationships factor was also statistically significant (r (218) = .589, p = .01) with what is considered to be a large effect size (Cohen, 1988).

Discussion/conclusion/recommendations

This quantitative study in two regions of Tennessee and Virginia builds upon previous studies that emphasise the value of assessing teachers’ knowledge, self-efficacy, and participation in trauma-informed care training. The PECE-TICKCR scale was adapted from the TIC-DS (Goodwin-Glick, 2017) and validated for the purpose of this study. The PECE-TICKCR may be useful for future organisations or administrators wishing to assess primary education teachers’ knowledge and confidence of trauma-informed practices and the training topics needed. The research objectives and descriptions of conclusions are provided in detail below.

The first research objective sought to reveal the level of knowledge of trauma that teachers reported. A large percentage of teachers from the current study reported they were knowledgeable or very knowledgeable about the impact of trauma on students. However, knowledge of community resources for families and students, and knowledge about the steps to take if a student is identified as a trauma victim were identified as areas of need, which aligns with previous research that showed teachers want to know how to provide the best care to students dealing with trauma and desire more overall knowledge of how to provide trauma-informed care for children and families (Alisic et al., 2012). Implementing a trauma-informed approach requires integrating knowledge of trauma into all areas of support including instructional, behavioural, and psychological (Harris & Fallot, 2001). Teachers often struggle with their role in working with a student exposed to trauma, knowing what the next steps might be to take when aware of exposure (Alisic et al., 2012), and they feel they need better knowledge and skills regarding trauma-informed practices (Alisic, 2012). Many teachers view themselves as vital to meeting the needs of trauma exposed students, however, they often feel they do not have the knowledge to recognise and understand trauma nor understand the strategies needed (Reinke et al., 2011). Gaining knowledge of trauma may increase the enthusiasm and motivation of teachers for implementing strategies (Han & Weiss, 2005).

The second research objective sought to answer how teachers assess their level of self-efficacy in supporting students who have experienced trauma. Roughly half of the teachers surveyed reported they felt somewhat confident to not at all confident with de-escalating and managing student behaviours, taking appropriate steps if they suspect a student has experienced trauma, and supporting a student who has experienced trauma. This aligns with previous research (Onchwari, 2010; Reinke et al., 2011) that showed that teachers need training on specific strategies for working with students who have been exposed to trauma. Many teachers have not had the hands-on experience or the educational training to have accurate interpretations of the behaviours of students exposed to trauma (Alisic, 2012). Further training for teachers regarding the application of trauma-informed strategies when managing scenarios involving challenging behaviour could increase teachers’ self-efficacy in supporting students who have experienced trauma. Knowledge of trauma’s impact on children is important, however, teachers need to know how to apply the trauma-informed knowledge with confidence.

The teachers included in this study reported they were most confident in supporting positive relationships with students. As previously noted, all four items related to this factor resulted in high percentages of participants who felt very confident or confident. Having a positive relationship with a teacher or another adult in the school setting has a positive effect on the academic achievement and behaviour of students (Curby et al. 2009). Also, when children have a sense of belonging, it can increase their sense of motivation in school (Wentzel et al., 2010). Developing nurturing and supportive relationships is central to maintaining a trauma-sensitive environment. Positive interactions build trust between students and teachers and can go a long way in preventing challenging behaviours and meeting the needs of students where they are.

The third research objective was to determine the amount and type of training teachers have received related to childhood trauma. Most teachers have had training on the basics of childhood trauma. Teachers are more interested in taking their knowledge of trauma a step further and would like to learn more about the strategies, resources, and supports available to teachers, children, and families of children who have experienced trauma. This aligns with a qualitative study (Alisic, 2012) which found that teachers desire more knowledge and specific solutions for how to support students who have been exposed to trauma. A 2018 study (Morton & Berardi, 2018) revealed teachers indicated the need for more training because their teacher prep programs poorly prepared them for meeting the significant mental health needs of their students. Opportunities exist for school leaders to use the theoretical frameworks and research findings to support the need for trauma-informed professional development. One example is the trauma-informed education model (TIPE), which was created based upon a systematic literature review of trauma-aware practice models and student well-being literature (Stokes & Brunzell, 2019). TIPE is a model based on a whole school approach and includes three domains: (1) increasing self-regulatory abilities, (2) increasing relational capacities, and (3) increasing psychological resources for student well-being (Stokes & Brunzell, 2019). Chafouleas et al. (2016) provide a blueprint for a trauma-informed approach using a multi-tiered framework called the School-Wide Positive Behavior Interventions and Supports (SWPBIS). The SWPBIS framework helps align trauma-informed approaches with existing educational practices.

There is a growing need for evidence-based research on the implementation and impact of trauma-informed models. According to Chafouleas et al. (2016), there is a need for objective knowledge of implementing trauma-informed practices as well as rigorous evidence of the outcomes from said practices to ensure the efforts made by schools result in expected outcomes. There is also a need to gauge whether stakeholders, administrators, and educators find trauma-informed approaches acceptable and feasible (Chafouleas et al., 2016). Specific needs regarding teachers’ training regarding resources and supports for families could be more useful if evaluated on a local level due to the differences in the needs of children and families within the community as well as differences in the availability of resources between communities.

Based on the findings of this study, organisations working towards providing trauma-informed care might consider assessing the teachers and staff within an organisation to reveal the unique learning needs of that specific population. Understanding the specific learning needs of teachers allows for a more applicable and useful approach when designing professional development and training sessions. Teacher preparation programs should implement trauma training courses or curricula into current programs. A Midwestern graduate university (Canon et al., 2020) administered three courses to students on knowledge, attitudes, and strategies of trauma-informed care. The post-test (Canon et al., 2020) revealed an increase in the knowledge and skills of trauma-informed care. Educators are serving not only as educators, but mentors, surrogate parents, safety officers, caseworkers, and counsellors in what is often overcrowded and underfunded settings. The growing number of young children exposed to trauma entering classrooms supports the need for re-evaluating the training experiences of pre-service and in-service teachers regarding mental health and trauma-informed care.

Early Childhood Educators are critical support agents for young children who have experienced trauma. They are responsible for building relationships with their students and families in an effort to learn more about the strengths, interests, and needs of young children. Designing both the physical and emotional learning environment is key. Creating spaces that welcome children and families and providing opportunities for exploration and learning based on individual and group interests and needs guides our day-to-day pedagogy (Erdman et al, 2020).

Ethical considerations

The research team acquired permission from the University’s Institutional Review Board and local school administration to conduct the study. Informed, voluntary consent was obtained from all participants who were assured anonymity.

Limitations

The current study’s findings serve to inform organisational, professional development practices and as a voice for the knowledge, feelings, and needs of primary education teachers; however, there are several limitations to the current study that should be considered and addressed in future work. First, the data collection occurred during the worldwide COVID-19 pandemic. Teachers were entering uncharted territory along with added responsibilities and stress. Essentially, all participants were experiencing a form of trauma while living through and working during a pandemic. Secondly, there exists within the current survey a lack of a standardised method for measuring the specific amount of trauma-informed training received. Trauma-informed professional development can range from a one-hour workshop to a multi-day or even multi-phase training. Capturing information about specific dosage and content of trauma-informed training is difficult, which reduces the ability to generalise across studies. Future research should seek to capture specific aspects related to dosage and specific topics of trauma-informed training received by participants.

Another limitation is the lack of diversity among participants and settings. Ninety-one percent of the teachers in this study were Caucasian women who do not represent diversity but are an accurate representation of the population from the region that was polled. Future studies could seek participants in non-traditional teaching roles, including administrative roles, consider racial diversity, and include urban settings. This study was conducted by five white women. Three of the authors are PhD students and two are faculty academics from a university early childhood program. The research team has experienced the challenges of working with children whose behaviour is hard to understand because of the trauma they have experienced. Though the research team has tried to recognise how their previous experiences and their whiteness has impacted their research process and their interpretation of the findings, they acknowledge that researchers have biases that often remain hidden and can impact their work.

The wording within the demographic section of the survey may have been a limitation. Participants were asked to report the type of school setting in which they worked, choosing from suburban, rural, urban, combination of urban or suburban and rural, and it is possible that participants may have been unsure about which descriptor was most representative of their workplace. Also, the authors acknowledge the option “combination of urban or suburban and rural” may have been confusing to participants.

A final limitation is based on the type of data collected. Utilising a Likert-style scale allows for an ordinal psychometric measurement of attitudes, beliefs, and opinions. However, the Likert scale format does not reveal specific details about the knowledge teachers hold. The current survey was limited to fixed response options and did not allow the participants a platform to provide more detailed information. Acknowledging the current study only collected quantitative data, future studies should gather information through alternative sources, such as adding a qualitative component providing more in-depth evidence of trauma-informed knowledge, self-efficacy, and training experiences/needs.

References

Alisic, E. (2012). Teachers’ perspectives on providing support to children after trauma: A qualitative study. School Psychology Quarterly, 27(1), 51. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028590

Alisic, E., Bus, M., Dulack, W., Pennings, L., & Splinter, J. (2012). Teachers’ experiences supporting children after traumatic exposure. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 25(1), 98–101. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20709

American Academy of Pediatrics. (2014). Adverse childhood experiences and the lifelong consequences of trauma. Retrieved April 5, 2022 https://www.aap.org/en-us/Documents/ttb_aces_consequences.pdf

Berger, E. (2019). Multi-tiered approaches to trauma-informed care in schools: A systematic review. School Mental Health. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-019-09326-0

Bethell, C. D., Newacheck, P., Hawes, E., & Halfon, N. (2014). Changing epidemiology of children’s health. Adverse childhood experiences: Assessing the impact on health and school engagement and the mitigating role of resilience. Health Affairs, 33(12), 2106–2115. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0914

Blaustein, M. E. (2013). Childhood trauma and a framework for intervention. In E. Rossen & R. Hull (Eds.), Supporting and educating traumatized students: A guide for school-based professionals (pp. 3–21). Oxford University Press.

Brunzell, T., Waters, L., & Stokes, H. (2015). Teaching with strengths in trauma-affected students: A new approach to healing and growth in the classroom. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 1, 3–9. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000048

Canon, L. M., Coolidge, E. M., LeGeirse, J., Moskowitz, Y., Buckley, C., Chapin, E., Warren, M., & Kuzma, E. K. (2020). Trauma-informed education: Creating and pilot testing a nursing curriculum on trauma-informed care. Nurse Education Today, 85, 104256.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019). About the CDC-Kaiser ACE study. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved March 15, 2022 https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/aces/about.html

Chafouleas, S. M., Johnson, A. H., Overstreet, S., & Santos, N. M. (2016). Toward a blueprint for trauma-informed service delivery in schools. School Mental Health, 8, 144–162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-015-9166-8

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. L. Erlbaum Associates. Retrieved August 15, 2022 https://www.utstat.toronto.edu/~brunner/oldclass/378f16/readings/CohenPower.pdf

Courtois, C. A., & Ford, J. D. (Eds.). (2009). Treating complex stress disorders: An evidence-based guide. The Guilford Press.

Cronholm, P. F., Forke, C. M., Wade, R., Bair-Merritt, M. H., Davis, M., Harkins-Schwarz, M., Pachter, L. M., & Fein, J. A. (2015). Adverse childhood experiences: Expanding the concept of adversity. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 49(3), 354–361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2015.02.001

Curby, T. W., Rimm-Kaufman, S. E., & Ponitz, C. C. (2009). Teacher–child interactions and children’s achievement trajectories across kindergarten and first grade. Journal of Educational Psychology, 101(4), 912–925. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016647

Erdman, S., Colker, L., & Winter, E. C. (2020). Trauma & young children: Teaching strategies to support & empower. National Association for the Education of Young Children.

Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., Koss, M., & Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8

Forkey, H. (2019). Putting your trauma lens on. Pediatric Annals, 48(7), 269–273. https://doi.org/10.3928/19382359-20190618-01

Goodman, R. D., Miller, M. D., & West-Olatunji, C. A. (2012). Traumatic stress, socioeconomic status, and academic achievement among primary school students. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 4(3), 252–259. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024912

Goodwin-Glick, K. L. (2017). Impact of trauma-informed care professional development of school personnel perceptions of knowledge, disposition, and behaviors toward traumatized students. Graduate College of Bowling Green State University.

Han, S. S., & Weiss, B. (2005). Sustainability of teacher implementation of school-based mental health programs. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 33, 665–679. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-005-7646-2

Harris, M., & Fallot, R. D. (2001). Envisioning a trauma-informed service system: A vital paradigm shift. New Directions for Mental Health Services, 89(1), 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1002/yd.23320018903

Hillis, S., Mercy, J., Amobi, A., & Kress, H. (2016). Global prevalence of past-year violence against children: A systematic review and minimum estimates. Pediatrics, 137(3), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-4079

Jimenez, M. E., Wade, R. L., Lin, Y., Morrow, L. M., & Reichman, N. E. (2016). Adverse experiences in early childhood and kindergarten outcomes. Pediatrics, 137(2), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-1839

Loomis, A. M., & Mogro-Wilson, C. (2019). Effects of cumulative adversity on preschool self-regulation and student-teacher relationships in highly dense Hispanic community: A pilot study. Infants & Young Children, 32(2), 107–122.

Merrick, M. T., Ford, D. C., Ports, K. A., & Guinn, A. S. (2018). Prevalence of adverse childhood experiences from the 2011–2014 behavioral risk factor surveillance system in 23 states. JAMA Pediatrics, 172(11), 1038–1044. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.2537

Milot, T., Ethier, L. S., St-Laurent, D., & Provost, M. A. (2010). The role of trauma in the development of behavioral problems in maltreated preschoolers. Child Abuse & Neglect, 34(4), 225–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.07.006

Morton, B. M., & Berardi, A. (2018). Creating a trauma-informed rural community: A university-school district model. In R. M. Reardon & J. Leonard (Eds.), Making a positive impact in rural places: Change agency in the context of school-university-community collaboration in education (pp. 193–213). Information Age Publishing.

National Child Traumatic Stress Network. (2020). Child welfare trauma training toolkit. The National Child Traumatic Stress Network. Retrieved August 1, 2022 https://www.nctsn.org/resources/child-welfare-trauma-training-toolkit

Onchwari, J. (2010). Early childhood in-service and pre-service teachers’ perceived levels of preparedness to handle stress in their students. Early Childhood Education Journal, 37(5), 391–400. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-009-0361-9

Porche, M. V., Costello, D. M., & Rosen-Reynoso, M. (2016). Adverse family experiences, child mental health, and educational outcomes for a national sample of students. School Mental Health. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-016-9174-3

Prewitt, E. (2016). New elementary and secondary education law includes specific “trauma informed practices” provisions. Retrieved August 1, 2022 https://www.pacesconnection.com/g/aces-in-education/blog/new-elementary-and-secondary-education-law-includes-specific-trauma-informed-practices-provisions

Reinke, W. M., Stormont, M., Herman, K. C., Puri, R., & Goel, N. (2011). Supporting children’s mental health in schools: Teacher perceptions of needs, roles, and barriers. School Psychology Quarterly, 26(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022714

Reker, K. (2016). Trauma in the classroom: Teachers' perspectives on supporting students experiencing child traumatic stress. [Doctoral Dissertation]. Loyola University, Chicago. Retrieved September 5, 2019, from https://ecommons.luc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3145&context=luc_diss&httpsredir=1&referer=

Rothì, D. M., Leavey, G., & Best, R. (2008). On the front-line: Teachers as active observers of pupils’ mental health. Teaching and Teacher Education, 24(5), 1217–1231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2007.09.011

Shields, A., Ryan, R. M., & Cicchetti, D. (2001). Narrative representations of caregivers and emotion dysregulation as predictors of maltreated children’s rejection by peers. Developmental Psychology., 37(3), 321. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.37.3.321

Shonkoff, J. P., Garner, A. S., Siegel, B. S., Dobbins, M. I., Earls, M. F., Garner, A. S., McGuinn, L., Pascoe, J., & Wood, D. L. (2012). The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-2663

Smyth, M. (2017). Teachers supporting students affected by trauma. Social Justice and Community Engagement. 23. Retrieved September 5, 2019 https://scholars.wlu.ca/brantford_sjce/23

Stokes, H., & Brunzell, T. (2019). Professional learning in trauma informed positive education: Moving school communities from trauma affected to trauma aware. School Leadership Review, 14(2). https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/slr/vol14/iss2/6

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). (2014). SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Retrieved September 1, 2019 https://store.samhsa.gov/product/SAMHSA-s-Concept-of-Trauma-and-Guidance-for-a-Trauma-Informed-Approach/SMA14-4884

Terr, L. C. (1991). Childhood traumas: An outline and overview. American Journal of Psychiatry, 148(1), 10–20. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.148.1.10

The Illinois Aces Response Collaborative. (2017). ACEs for educators and stakeholders. Education Policy Brief, 1–13. Retrieved September 1, 2019 http://www.hmprg.org/wp-content/themes/HMPRG/backup/ACEs/Education%20Policy%20Brief.pdf

US Department of Health and Human Services. (2015). Child maltreatment 2015. The Administration for Children and Families. Retrieved August 2, 2021, from https://www.acf.hhs.gov/cb/report/child-maltreatment-2015

US Department of Health and Human Services. (2020). Attachment B: Office of Head Start Guidance on implementing a trauma-informed approach. ECLKCK. Retrieved August 2, 2021 fromhttps://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/publication/attachment-b-office-head-start-guidance-implementing-trauma-informed-approach

Wentzel, K. R., Battle, A., Russell, S. L., & Looney, L. (2010). Social supports from teachers and peers as predictors of academic and social motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 35, 193–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2010.03.002

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Considerations

The research team acquired permission from East Tennessee State University's Institutional Review Board and local school administration to conduct the study. The approval number is noted as, "c0220.19e. Informed, voluntary consent was obtained from all participants who were assured anonymity.

Conflict of interest

We have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Bilbrey, J.B., Castanon, K.L., Copeland, R.B. et al. Primary early childhood educators’ perspectives of trauma-informed knowledge, confidence, and training. Aust. Educ. Res. 51, 67–88 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-022-00582-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-022-00582-9