Abstract

Using two novel online surveys collected in May and November 2020, we study the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on Spanish households. We document a large and negative effect on household income. By May 2020, the average individual lived in a household that had lost 16% of their pre-pandemic monthly income. Furthermore, this drop was highly unequal: while households in the richest quintile lost 6.8% of their income, those in the poorest quintile lost 27%. We also document that the pandemic deepened the gender-income gap: on average, women experienced a three-percentage point larger income loss than men. While this is consistent with previous findings in the literature, in this paper we document that this effect is driven by women from middle-income households with kids. Finally, we provide evidence that Spanish individuals experienced moderate declines in their levels of psychological well-being. This effect is not different for individuals living in rich or poor households, but the reasons behind well-being losses do differ: richer individuals are more concerned about loss of contact with dear ones, while low-income individuals are more likely to mention loss of income and employment as a key source of emotional distress.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a profound impact on the lives of individuals throughout the world. Most countries have experienced restrictions to mobility, interpersonal contact, and economic activity that have affected income levels and the well-being of individuals. The burden of the COVID-19 shock is likely to have been different across groups of individuals. A number of studies, recently summarized by Stantcheva (2021), provide evidence that the COVID-19 pandemic is likely to deepen inequality along a number of different dimensions. Foremost among them is the potential of the COVID-19 shock to increase income inequality across individuals of most countries: loss of employment has been higher among temporary workers and low-skilled occupations have been most heavily affected by lockdowns due to the difficulties in conducting them remotely, as shown by Adams-Prassl et al. (2020).

Despite the indications that the COVID-19 may have exacerbated inequality, documenting the precise effects is difficult. Inequality is typically measured using large household surveys implemented by national statistical agencies. However, these data usually come with a substantial delay. For instance, the latest release by Eurostat of the Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC) dates from April 2021.Footnote 1 However, the release only provides data until 2019. Furthermore, when the data corresponding to the year 2020 become available, they will provide a snapshot of the level of inequality, but will not uncover the dynamics across critical points in time of the pandemic. The delays in the availability of official statistics also hinder the ability of an adequate and timely policy response to the changing reality.Footnote 2 A number of recent studies have explored alternative data sources. For instance, Chetty et al. (2020) and Aspachs et al. (2020) use data from the banking sector, while Clark et al. (2020) and Adams-Prassl et al. (2020) use data from online surveys.

In this paper, we contribute to this literature through the collection of two new online surveys representative of the population of Spain. Due to the characteristics of the Spanish economy, the country is particularly vulnerable to the economic shock of COVID-19. Spain has one of the largest shares of temporary workers in the EU, and it also has a high dependency of the tourism sector, which has been highly disrupted during the COVID-19 pandemic (Banco de España 2021). Furthermore, Spain has been severely affected by the pandemic, particularly at the initial stages, being one of the countries in the EU with the largest number of deaths per capita.Footnote 3

We collected two online surveys during the months of June and December of 2020 from a large sample of individuals who reside in Spain. In this study, we focus on the 2678 individuals that completed both questionnaires and provided full information in key variables such as monthly income, occupation, and measures of well-being. Our resulting sample is representative of the Spanish population in terms of gender, education, and region of residence. Our sample also provides a good approximation of the pre-pandemic income distribution in Spain. Furthermore, we weight observations using sampling weights to guarantee that our findings are representative at the level of the Spanish population. We collected rich information on individuals income levels and labor conditions. In particular, we asked respondents about their levels of individual and household disposable monthly incomes at the time of each survey using narrow income brackets.Footnote 4 We also asked them how these income levels have changed since the beginning of the pandemic. Hence, we can trace the evolution of their incomes during the most intense phase of the pandemic. In addition to this, we collected broad measures of well-being and asked individuals for the reasons behind declines in life satisfaction. These measures allow us to go beyond income measures and document how the socioeconomic situation has affected their well-being.

Using these data, we provide evidence that the COVID-19 pandemic represented a large and unequal shock for the Spanish population. We examine how the decline in income has affected households across the income distribution. We show that the poorest households experienced substantially larger shocks relative to richer households. While households in the richest quintile of the distribution had lost 7% of their household income by May 2020, the decline was of 28% for those in the poorest quintile. These effects are comparable to those experienced in the UK and the USA and larger than those in Germany (Adams-Prassl et al. 2020).Footnote 5

Next, we study the loss of income by gender. On average, women’s incomes dropped by around three-percentage points more than men’s by May 2020, relative to their 2019 income. This difference persisted by November 2020. There are also important differences along the income distribution: while men and women living in the richest or poorest quintiles experienced a similar income loss, females living in the middle quintiles saw larger losses than males. Furthermore, while income recovered to a substantial extent for males between May and November 2020, income recovery was slower for women, particularly for those in the middle quintiles. While further investigation is needed, we provide some evidence that this result is driven by a higher propensity of women from middle-income households with kids to drop out of the labor market. This may have been motivated by the difficulties in family conciliation during the pandemic.

We then study changes in income by employment status. Our results suggest that self-employed individuals experienced the largest decreases in their disposable income. Salaried and unemployed individuals also suffered large income losses. Retired individuals experienced smaller but non-negligible losses, highlighting the strength of the pension system in accommodating negative shocks but also revealing the potential impact of the shock on other sources of income like rents. The effects were also unequal within each employment status across the income distribution, with low-income self-employed and salaried individuals experiencing larger losses than their higher-income counterparts. We also examine how the impact varied by type of contract and find that temporary workers experienced a larger drop in income, but that permanent workers also suffered large losses. We also document that the drop in income was larger among individuals in sectors considered as non-essential during the state of alarm and lockdown.

Finally, we examine the effect of the pandemic on self-reported measures of well-being. We find that individuals in the poorest quintiles had slightly lower levels of well-being relative to the richest quintiles by May 2020. Nevertheless, the income gradient of well-being is small: all quintiles report average measures between 5 and 6 (in a scale from 0 to 10). However, the reported reasons for reductions in well-being do differ substantially across the income distribution. Loss of employment or income is a more important concern for low-income individuals relative to higher-income households. In contrast, concerns over loss of contact with family members increase with income. Concern over conciliation is relatively less frequent, but it is concentrated on families in the middle of the income distribution and is particularly high among females. We also examine how the reasons for declines in well-being change between May and December. While the prevalence of feelings of uncertainty about the future declines, concerns over low contact with loved ones substantially increase across all income quintiles: 52% of respondents chose this option as a reason for loss of well-being in May; by November, the percentage increases to 74%.

Overall, these results help us uncover important dimensions of the economic effects of COVID-19 in Spanish households. First, the findings indicate that the shock was not neutral across the income distribution and exacerbated preexisting income inequalities. While previous recessions in Spain have also deepened inequality, see Bonhomme and Hospido (2017), the magnitude of the shock and the increase in inequality estimated in this paper are larger than in previous crises. This paper also shows that the patterns of recovery were different across income groups, with some groups experiencing persistent negative effects on their income. Finally, it illustrates that gender differences have differential patterns across the income distribution, with persistent negative shocks for females in middle-income households.

This paper contributes to the literature that tries to document the effects of COVID-19 on the evolution of inequality on several dimensions—see Stantcheva (2021) for a recent literature review. In the context of Spain, two previous studies have studied the evolution of inequality during the pandemic, finding mixed evidence. Clark et al. (2020) collect data from online surveys in five European countries, including Spain, between May and November 2020. This study finds small increases in inequality by May 2020 and declines in inequality by September 2020.Footnote 6 However, it is unclear whether their sample is representative of the Spanish population. According to their estimates, average incomes in Spain barely change between January and May 2020 (less than 1%), and they even increase between January and September 2020. This is hard to reconcile with the large declines in GDP and with the large increases in unemployment during this period.Footnote 7 Furthermore, their measure of income is based on respondents selecting income in large income bands. For example, their lowest income band ranges from 0 to 1250€ per month. According to EU-SILC 2019, 60% of individuals in Spain would have incomes in this interval. Hence, the data collection may hinder the ability of detect changes in the income within this large band and, hence, in income inequality.

Another approach to measure the evolution of inequality in Spain has been undertaken by Aspachs et al. (2020). They use data from a large Spanish bank on income measures and government transfers of their clients. They do find large increases in inequality during the first months of the pandemic. The Gini coefficient of pre-tax income increased from 0.45 to 0.55 between February and May 2020. Accounting for government transfers, the increase in inequality is smaller, but nevertheless positive: The post-transfer Gini coefficient increases from 0.38 to 0.42 between February and May. We differ from their study in several respects. First, their sample is limited to customers of a single bank, which may be selected toward particular types of individuals or regions. Second, we have richer information on household composition and income. Household-level income may provide a better characterization of individuals’ well-being, particularly in cases in which one member of the couple specializes in home production or for individuals enrolled in tertiary education. Third, our data allow us to measure well-being through the evaluation of psychological status, as well as other attitudinal measures.

Our paper also contributes to the literature studying emotional well-being changes after the pandemic. In this regard, our work is related to Foremny et al. (2021), who document a considerable deterioration of mental health during the pandemic in Spain. While both studies address the broad issue of well-being, their focus is more on the incidence of mental health problems, such as depression or anxiety, while our study focuses on general emotional well-being measured using a gradient from 0 to 10. Also, our data allow us to provide evidence on the reasons for well-being loss.

The rest of the paper proceeds as follows: In Sect. 2, we describe the context in which our surveys were collected and we present the data. In Sect. 3, we present our main results. In Sect. 4 we conclude.

2 Context and data

The data used in this project originate from two online surveys conducted by the authors in June and December of 2020. Since respondents are likely to answer on the basis of their situation in the previous month, we refer to each wave as corresponding to the months of May and November, respectively.Footnote 8 The surveys were conducted by YouGov, which is a well-established data analytics firm.Footnote 9 The company has access to a large pool of individuals that have been recruited through online adds and that regularly respond to surveys on a variety of topics. Respondents accumulate points for answering surveys and they can exchange points for small gifts.

Context The environment in which the two survey waves were conducted was different. In May 2020, Spain had just exited from one of the strictest lockdowns in Europe. For almost two months all out-door activities were banned. Individuals could only leave their house in order to buy necessity goods or going to work. Between mid-March and the end of April, only economic activities declared as “essential” were allowed to fully operate. The sectors considered essential were health care, nursing homes, food and basic necessities stores, pharmacies, media, transportation, financial sectors, and a few others.Footnote 10 Sectors declared non-essential had to conduct their activities online. Starting in early May, restrictions were progressively lifted and some non-essential economic activities resumed on-site. This period was referred as the de-escalation period. By the time the first wave of our survey was conducted in June 2020, restrictions were further relaxed and many economic activities, such as retail and hospitality sector, had resumed, albeit with restrictions on hours of operation, maximum capacity, and sanitary measures. The incidence of COVID cases was low (13.8 cases per 100,000 inhabitants during the last two weeks of May 2020).Footnote 11

By the end of June 2020, Spain entered a phase labeled as “new normality”, where most economic activity had resumed. Contact-tracing was being reinforced, and containment of the virus was pursued as a policy objective. Nevertheless, COVID-19 incidence continued to increase during the second half of 2020. In October 25, the government re-instated the state of alarm and restrictions were strengthened. By the time the second wave of our study was collected in late November 2020, there were worrying concerns about a growing COVID-19 incidence. During the last two weeks of November, incidence was 275 cases per 100,000 inhabitants.Footnote 12 There was also substantial uncertainty regarding the type of mobility and social-gathering restrictions that would be imposed during the upcoming Christmas holidays.

Study Sample We surveyed individuals older than 18 that reside in Spain. We collected information on the respondents’ demographic (gender, nationality, age, region of residence) and socioeconomic characteristics (employment status, occupation, income), as well as on measures of their subjective well-being. The full questionnaire can be found in Appendices C (for the first wave) and D (for the second wave). The survey also contained an experimental part, which we do not study in this paper. The experiment should not affect our results as most of the variables used in this paper were asked before the experimental section.Footnote 13

The sampling framework of the first wave was designed to be representative of the Spanish adult population according to age, gender, region of residence, and education level.Footnote 14 All the individuals from the first round of the survey were re-contacted in the second wave. We are particularly interested in tracking the evolution of the socioeconomic situation of individuals over this sample period. Hence, we focus our attention on the sample to the 2678 individuals that answered the complete questionnaire in both waves and that provided information regarding their income and self-reported well-being.Footnote 15

Our resulting sample provides a good approximation to the Spanish adult population. In Table 1, we show a number of basic statistics regarding the composition of our sample when compared to the Spanish population as measured by the National Institute of Statistics (INE) in 2019. Our sample matches quite closely the gender and age distribution of the Spanish adult population. In Table 1, we also report coverage of six different geographic regions of Spain, each comprising a few Autonomous Communities.Footnote 16 Finally, we match reasonably well the level of education of the Spanish population. We have a slightly larger representation of tertiary educated respondents and lower representation of low educated individuals. However, the disparities are moderate.Footnote 17 In order to further strengthen the representativeness of our sample, in the rest of the analysis we use sample weights.Footnote 18

Summary Statistics In Table 2, we present additional summary statistics of the main variables used in the analysis. Respondents’ ages range between 18 and 91 years old, with an average of 48 years of age. Fifty percent of respondents are female. On average, individuals in our sample have 11 years of education, which is equivalent to finishing upper secondary education.Footnote 19

Individuals were asked about their employment status in 2019, which we classified in five categories: salaried, self-employed, retired, unemployed, or out of the labor force, which also includes students. Among the salaried and self-employed, we collected information on whether their sector was declared “essential” by the government at the beginning of the pandemic. These sectors were allowed to continue their activities, while sectors considered “non-essential” experienced a suspension of all activities that could not be done remotely until late April 2020.

We collected detailed data on monthly income levels both for the individual and for their household. First, we asked for their incomes before the pandemic. In particular, we asked for their net (after-tax) total income, including wages, earnings from professional activities, pensions, and government transfers during the average month of 2019.Footnote 20 Individuals were asked to select an interval that includes their level of income. We take the midpoint of each interval as a proxy of their income level.Footnote 21 In order to make comparisons across households, we define equivalent income for a four-member household formed of 2 adults and 2 children. We follow the convention used in Eurostat and other statistical agencies and assign children a weight of 0.5 when assessing their consumption demands. Hence, we divide the reported household income by the number of adult-equivalent individuals in the household, and then multiply by three, which corresponds to a household of 2 adults and 2 children. On average, the monthly disposable income of a household with four members in 2019 was of 2668€ per month. We use the same scale to elicit the level of income of the individual respondent. Our average respondent earned 1188€ per month.

Individuals were also asked about how their household and individual incomes had changed at the time of responding with respect to their income at the start of the pandemic. We also collected this information discretely by asking individual to choose between income-change intervals.Footnote 22 Using this information, we calculate the percent change in income by dividing the reported change in levels by the 2019 income level.Footnote 23 The average change in household income relative to 2019 is \(-16\)% by May 2020 and \(-11\)% by November 2020. The magnitudes for changes in individual income are similar. The large drop in income by May is comparable to the drop in per capita GDP as reported by national statistics. The change in GDP per capita between the fourth trimester of 2019 and the second trimester of 2020 was of \(-5.9\)%. The change between the last trimester of 2019 and the last trimester of 2020 was \(-9.9\)%.Footnote 24 The changes in income are very similar for household and for individual income. This is an indication of the accuracy of the information reported and of the representativeness of our data of the adult population.

Finally, we recorded information on self-reported levels of well-being. In particular we asked the following question: “In a scale from 0 to 10, where 0 indicates great discomfort or depression and 10 complete happiness, how would you evaluate your level of emotional well-being?” Individuals reported an average level of well-being of 5.8 in May 2020 and of 5.3 in November 2020. Next, we asked individuals to compare their current well-being with that from before the pandemic. We asked individuals to select one of the following options, which we codified in a scale from \(-2\) to 2: it has decreased a lot (= \(-2\)), it has slightly decreased (= \(-1\)), it has remained more or less the same (=0), it has slightly increased (= 1), and it has increased a lot (=2). The average value of the codified variable is \(-0.38\) in May 2020 and of \(-0.54\) in November 2020. These results indicate that, on average, individuals have experienced moderate decreases in well-being, and the loss in well-being became larger over time.

Finally, individuals who responded that their well-being had decreased (slightly or a lot) were asked about the main reasons for this decrease. Individuals were offered a number of potential reasons and were allowed to select more than one. On average, individuals selected 2.4 reasons in the first wave and 2.2 in the second wave. The most frequently reported reason was uncertainty about the future, which was selected by 82% of respondents in May 2020. The subsequent reasons in order of prevalence in the May survey are: reduced of contact with dear ones (52%), concerns about loss of employment (25%), health issues (14%), difficulty to conciliate work and childcare (8%).Footnote 25 It is interesting to examine how the motives behind the decreases in well-being changed between our two waves. While uncertainty about the future seem to have slightly declined, loss of contact with dear ones increased by 18 percentage points. The prevalence of the other motives for concern changed to a lesser extent.

3 Results

3.1 Effects on income

Inequality across the Income Distribution In Table 2 we described how a number of key measures of income and well-being evolved, on average, during the pandemic. In this subsection we examine whether the magnitude of these changes differ across the income distribution.

We begin by classifying individuals according to quintiles of household income in 2019. For each respondent, we compute the equivalent income for a four-member household, as described in the previous section. We then divide the sample in five quintiles, each comprising approximately 20% of respondents. Quintiles are sorted from poorest to richest, and comprise individuals in the following intervals of equivalent household income per month: quintile 1 (from 0 to 1260€); quintile 2 (from 1261 to 1950€); quintile 3 (from 1951 to 2700€); quintile 4 (from 2700 to 4050€); quintile 5 (from 4050 to 24,000€).

Change in household income between 2019 and 2020, by quintile. Notes: The bars show the percentage change in household income between 2019 and May 2020. The diamonds indicate the percentage change for the period between 2019 and November 2020. Respondents are grouped in five quintiles according to their household income in 2019: quintile 1 corresponds to the poorest quintile and quintile 5 to the richest

Figure 1 reports the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic in household income for each quintile of the income distribution. The bars represent the percentage change in household income between the pre-pandemic level (2019) and May 2020 whereas the diamonds indicate the change between the pre-pandemic level and November 2020. We find large declines in household income throughout the income distribution. The figure also reveals that the magnitude of the income decline is uneven across households: While the poorest quintile lost a 27% of their income by May 2020, the richest quintile lost around 6.5% during the same period. The income gradient of loss of income is clear, with poorest households experiencing larger percentage changes.

We also examine the extent to which incomes recovered by November 2020. Most quintiles experienced some degree of recovery. Nevertheless, the inequality-widening nature of the shock persisted: while the richest quintile had lost 4% of their income by November 2020, the poorest quintile experienced a 18% reduction.

Appendix Table 5 presents the precise statistics shown in this figure. Furthermore, it provides additional tests. In particular, we find that the differences in change of income with respect to the richest quintile are all statistically significant at the 5% level. Furthermore, the quintile dummies are jointly statistically significant at the 1% level. The rest of Tables in Appendix B provide table counterparts for each of the main figures in the text. In general, the quintile indicators and the other geographic characteristics are highly statistically significant predictors of changes in income.

In order to set our results in comparison with previous studies, we calculate the Gini coefficient in three different points in time, 2019, May of 2020 and November 2020. The resulting estimates are 0.36, 0.39, and 0.38, respectively.Footnote 26 An increase of 0.03 points in the Gini coefficient is large in magnitude. For instance, the Gini coefficient of the distribution of income in the USA has increased by a similar amount between 1992 and 2018, which is recognized as a period of substantial deepening in the inequality of the income distribution of the USA.Footnote 27

Change in individual income, by quintile. Notes: The bars show the percentage change in individual-level income between 2019 and May 2020. The diamonds indicate the percentage change for the period between 2019 and November 2020. Respondents are grouped in five quintiles according to their household income in 2019: quintile 1 corresponds to the poorest quintile and quintile 5 to the richest

Figure 2 plots the evolution of the Gini coefficient as obtained in our data together with the evolution from the previous years as reported by the Spanish Statistical Agency (INE). The latter source is only available until 2019. It shows a slight decline over time in the level of inequality during the period 2017–2019. Our measure of the Gini coefficient is slightly larger in magnitude, albeit in the same ballpark. More importantly, our data indicate that there has been a sizeable increase in the Gini coefficient after the outbreak of the pandemic.Footnote 28

Next, we examine changes in individual-level income. Figure 3 presents results analogous figure to Fig. 1, when changes in income are defined at the individual-level. Note that we continue to classify individuals in quintiles according to their household income in 2019. Household income provides a better measure of the standards of living of individuals, particularly those out of the labor force and dedicated to home production. The results indicate that declines in individual-level income were also larger among individuals in the poorest quintiles of the household-income distribution. The income-gradient of income loss is not as large as when we examined changes in household income, but it is, nevertheless, economically significant. We also observe that there was a substantial recovery of incomes by November 2020. The recovery was similar across income deciles, hence, not altering the inequality-widening nature of the shock.

Change in individual income, by gender. Notes: The bars show the percentage change in individual-level income between 2019 and May 2020. The diamonds indicate the percentage change for the period between 2019 and November 2020. Respondents are grouped in five quintiles according to their household income in 2019: quintile 1 corresponds to the poorest quintile and quintile 5 to the richest. The statistics are presented by gender of the individual respondent

Inequality across Genders Next, we try to unbundle the economic shock on the basis of other dimensions. First, we study whether men and women have been differently affected by the shock. Figure 4 plots the change in individual income by gender, as a function of pre-pandemic household income. On average, women experienced slightly larger declines in income: a regression of the change in income on a female indicator indicates that women experienced a decline in income 3.8 percentage points larger than men by May 2020, and of 3.9 by November 2020 (both estimates are statistically significant at the 5% level). Furthermore, the analysis by income quintile uncovers interesting differences across the income distribution. The larger drop in income of women relative to men is taking place in households in the middle of the income distribution (quintiles 2 and 3, in particular). For the poorest and richest ones (quintiles 1,s 4 and 5), the gender gap in income loss is much smaller. Furthermore, while income recovered to a substantial extent for males between May and November 2020, the process of income recovery was slower for women, particularly those in the middle quintiles. One possible explanation for the larger and more persistent decline in income of middle-class women may be that some females may have been driven out of the labor-force during the pandemic, as they undertook a larger share of the responsibilities in home production during the pandemic (Farre et al. 2020).

To examine this possibility, in Appendix Fig. 13 we show the share of respondents that kept their job, were under a temporary lay-off scheme, or lost their job by May 2020. We report these statistics by gender and income group. The sample is restricted to salaried workers, which represent 51% of our sample. The results indicate that the largest gender gap in terms of loss of employment takes place for income group 2 (which aggregates quintiles 2 and 3). More generally, these results are consistent with previous studies that have pointed out that the COVID-19 pandemic has widened the gender gap. For instance, Alon et al. (2021) find that, contrary to previous recessions, the economic downturn generated by COVID-19 has generated larger employment losses for women than for men.Footnote 29 Our results point to a similar direction for the Spanish case. Furthermore, we provide evidence that the widening of the gender gap might have been specific to women living in middle-class households.

In Appendix Table 15 we provide further suggestive evidence of the potential drivers of these effects. In particular, we present the results of regressing an indicator for having lost employment (more specifically, becoming unemployed or being under a temporary layoff scheme (ERTE)) on a female indicator, a high-income indicator, and the interaction of the two. To streamline the presentation the high-income dummy takes value 1 for quintiles 2 and above.Footnote 30 Finally, we divide the sample in two groups: individuals with children (columns 1 and 2) and without children (columns 3 and 4). The results suggest that the higher propensity of high-income women to drop out of the labor force is present only in families with children. For instance, in column 1 we observe that, among low-income individuals with kids, females are less likely to drop out of the labor force than men (0.012 lower probability). However, among high income individuals, females are 9 percentage points more likely to drop out of the labor force than men (0.09 = − 0.012 + 0.102). When we compare this result with column 3 (no kids) we find that this effect disappears: high income women without kids are not more likely to drop out of the labor force than men of similar income. Columns 2 and 3 show that the results are robust to including dummies for types of occupation interacted with a female dummy. If anything the results become stronger, with the interaction term of column 2 increasing in magnitude and significance (the p-value is 0.137). This evidence suggests that women across the income distribution experienced a different evolution of their labor force participation, particularly when they had kids. In particular, it suggests that family conciliation difficulties may have been an important determinant of dropping out of the labor force. A key question is why these conciliation difficulties may not have been at play for women with kids in the poorest quintile. One potential answer is that for these women, dropping out of the labor force may not have been an option because their earnings may have be needed to sustain the family.

Inequality across the Age Distribution In Fig. 5, we examine differential effects by age groups. We decompose the population in four age groups: younger than 31, 31 to 45, 46 to 64, and over 65 years of age. Note that due to sample size limitations we bundle the 5 quintiles in just two income groups. Group 1 includes individuals from the poorest two quintiles, whose equivalent household income is below 1950€ per month in 2019. Group 2 includes individuals from the top 3 quintiles. With the only exception of individuals above 65 years of age, all other age groups experienced large declines in individual income. This finding illustrates the strength of the pension system in shielding households from negative macro-economic shocks. Consistent with previous findings, individuals that belong to poorer families experience larger declines in income relative to individuals from richer families. Interestingly, among individuals younger than 65 and once we hold constant the income group, there is not a clear relationship between age of the individual and the magnitude of the initial income shock experienced by May 2020. In other words, the heterogeneity in the magnitude of the shock is larger across the income distribution than across the age distribution. Nevertheless, the speed of recovery does seem to differ by age, with individuals below 31 years of age recovering faster relative to older ones. The persistence of the initial income shock seems particularly larger for individuals with ages between 31 and 64 in the poorest group.

Inequality across Pre-pandemic Employment Status Next, we examine the change in incomes of individuals by their employment status before the pandemic. We group individuals in one of the following categories: self-employed, salaried worker, unemployed, and retired, according to their status shortly before the pandemic. We continue to group individuals in two different income categories as described in the previous figure. Figure 6 shows the results. Self-employed individuals are the ones that experience the largest decline in income in both income categories, particularly in May 2020. Salaried individuals also experience large drops in income, particularly among the poorest income group. The unemployed group experiences similar declines in income across both groups.Footnote 31

Change in individual income, by age. Notes: The bars show the percentage change in individual-level income between 2019 and May 2020. The diamonds indicate the percentage change for the period between 2019 and November 2020. Respondents are grouped in two income groups: group 1 includes individuals in the poorest two quintiles, whose equivalent household incomes were lower than 1950€ per month in 2019; group 2 includes individuals from the top three quintiles. We decompose individuals by age groups as shown in the legend

Change in individual income, by employment status. Notes: The bars show the percentage change in individual-level income between 2019 and May 2020. The diamonds indicate the percentage change for the period between 2019 and November 2020. Respondents are grouped in two groups: group 1 includes individuals in the poorest two quintiles, whose equivalent household incomes were lower than 1950€ per month in 2019; group 2 includes individuals from the top three quintiles. We decompose individuals by the employment status they had before the pandemic, in 2019, as shown in the legend

Finally, retired individuals experience modest declines in their incomes. While self-employed and salaried individuals experience the largest drops in income, they also exhibit the largest recoveries by November 2020. Nevertheless, even by November 2020 these individuals had lost between 10 and 30% of their pre-COVID-19 income. These results indicate that the nature of the economic activity of individuals was a key determinant of the intensity of the economic shock generated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

In Fig. 7 we focus on self-employed and salaried individuals. Among this set of respondents, we collected information on their sector of activity. In particular, we asked them whether their type of economic activity was declared as “essential” during the state of alarm declared in March 14, 2020.Footnote 32 The figure indicates that individuals in activities declared as non-essential were hit harder by the economic shock. However, even individuals in essential sectors experienced large declines in their incomes. By November 2020, the self-employed in non-essential sectors experienced the largest recovery, while those in essential sectors had more persistent shocks. These results highlight that even individuals in essential sectors that were allowed to continue their operations experience significant negative spillovers in their overall economic activity.

Change in individual income of salaried and self-employed income. Notes: The bars show the percentage change in individual-level income between 2019 and May 2020. The diamonds indicate the percentage change for the period between 2019 and November 2020. Respondents are grouped in two income groups: group 1 includes individuals in the poorest two quintiles, whose equivalent household incomes were lower than 1950€ per month in 2019; group 2 includes individuals from the top three quintiles. The sample is restricted to individuals who were salaried workers or self-employed in 2019. We decompose individuals in both sectors by whether their sector was declared essential or not during the state of alarm declared in March 14, 2020

Change in individual income of salaried employees, by type of contract. Notes: The bars show the percentage change in individual-level income between 2019 and May 2020. The diamonds indicate the percentage change for the period between 2019 and November 2020. Respondents are grouped in two income groups: group 1 includes individuals in the poorest two quintiles, whose equivalent household incomes were lower than 1950€ per month in 2019; group 2 includes individuals from the top three quintiles. The sample is restricted to individuals who were salaried workers in 2019. We decompose individuals depending on their job status by 2019. In particular by whether they had a temporary or permanent contract

Finally, we study differences by type of contract: temporary or permanent. Spain is characterized by a “dual” labor market, with a very high share of temporary workers. This has been shown to have an impact on how the labor market reacts to recessions, generating large employment losses, especially among temporary workers (Bentolila et al. 2012). In Fig. 8 we plot income change among salaried workers, divided by the type of contract they had in 2019. The figure indicates that income losses have been higher for temporary workers, but also substantial for permanent ones. However, the speed of income recovery seemed larger for temporary workers than for permanent ones.

Inequality and Changes in Employment Status during the Pandemic One of the key predictors of loss in income is becoming unemployed or transitioning to a temporary layoff scheme (i.e., ERTE). The indicators of these rough categories of changes in job status can explain 33% of the variation in changes in individual-level income. However, the incidence of job loss is strongly associated with income quintile. Appendix Fig. 13 already documents this pattern: individuals in the bottom 20% of the income distribution are at least twice as likely to lose their job or transition to ERTE than individuals at higher levels of income.

Well-being levels and change, by income. Notes: The bars show the level of well-being by May 2020 in a scale from 0 to 10. The diamonds indicate the level of well-being by November 2020. Respondents are grouped in five quintiles according to their household income in 2019: quintile 1 corresponds to the poorest quintile and quintile 5 to the richest. The dots correspond to the changes in well-being between the start of the pandemic and May 2020. The categorical change has been coded on a scale from \(-2\) to 2, which is represented in the right-hand-side y-axis. Positive levels correspond to improvements in well-being, while negative levels represent declines in well-being

3.2 Effects on well-being

Evidence from other countries suggests that the pandemic has had a negative impact on psychological well-being (Ettman et al. 2020). Here we provide novel evidence for the Spanish case. Figure 9 plots the reported (individual) well-being on a 0–10 scale for individuals across 2019 household income quintiles. We find that individuals in the poorest quintiles have slightly lower levels of well-being relative to the richest quintiles by May 2020. Nevertheless, the income gradient of well-being is small: all quintiles reporting average measures between 5 and 6.2. The levels of well-being by November 2020 is slightly lower for most quintiles. We also asked individuals how their subjective well-being has changed with respect to the pre-pandemic level and we codified this measure between \(-2\) and 2, where positive values mean improvements in well-being and negative values mean declines. We plot reported changes in well-being as dots whose values can be found in the right-hand side y-scale. On average, people report having experienced moderate decreases in well-being, with an average value of our codified variable of \(-0.38\). However, there is not a clear income gradient in the change in well-being. Overall, these results suggest that there are small differences in levels or changes in aggregate well-being across the income distribution. If anything, low-income individuals have lower levels of well-being, but this is something that seems to pre-date the COVID-19 pandemic.

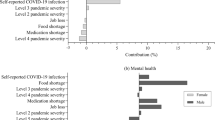

Nevertheless, there are important differences along the income distribution on the factors that influence emotional well-being. We illustrate this in Fig. 10. Among individuals who responded that their well-being had decreased (slightly or a lot) during the pandemic, we asked for the main reasons. Individuals were offered a number of potential reasons and were allowed to select more than one. In the figure, we report the fraction of individuals from each quintile that select a given category. We focus on the 5 most prevalent reasons: uncertainty about the future, reduced of contact with dear ones, worries about employment loss, health issues, and difficulties in conciliation of work and childcare.

Reasons for loss of well-being, by income. Notes: The bars indicate the fraction of respondents that selected each reason for the decline in well-being in May 2020. The diamonds indicate the fraction of respondents that selected each reason by November 2020. The questions were only asked to respondents that indicated that the experienced a decline in their levels of well-being. Individuals could select multiple reasons

The figure reveals at least three important findings. First, uncertainty about the future is the reason that is most frequently mentioned (by around 80% of individuals). Interestingly, this concern only decreases mildly by November 2020, which suggests that households perceived uncertainty remained high at that point. Second, we find a clear income gradient for the following two main concerns: while concerns over loss of employment was a more prevalent concern among poorer deciles, the opposite happens for worries over loss of contact with dear ones. The other reasons do not have a clear income gradient. Finally, there were some sizable changes over time. The most salient one refers to loss of contact with dear ones, which increase by 20 points in the prevalence of a main concern (from 52% in May 2020 to 72% in November 2020). The increase is similar across all income deciles. This highlights that the psychological costs of restriction to inter-personal contact may have been sizable during this period.

4 Conclusion

In this paper, we have presented novel evidence on the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on Spanish households. The data used in this paper come from two online surveys collected during May and November of 2020. The use of online surveys provides a powerful tool to examine, almost in real time, the evolution of household incomes during one of the worst economic crises of the last decades, as well as their consequences on psychological well-being.

The main findings of this study are the following. First, we document a large and negative effect on household income. By May 2020, the average household in Spain had lost 16% of their pre-pandemic income. By November 2020, the average household had only recovered 5 points of this drop. Second, the size of the economic shock was highly unequal. While households on the richest quintile lost 6.8% of their income by May 2020, the drop in income by the poorest quintile was 27%. As a result of this shock, the Gini coefficient experienced an increase of 3 points, from 36 in 2019 to 39 by May 2020. This increase is comparable to the cumulative increase in the Gini coefficient of the income distribution of the USA in the last three decades, which is a well-known case of large increase in inequality (Piketty et al. 2018). Third, the negative effects on income were larger for women than for men. Hence, we confirm previous findings in the literature that indicated the widening of the gender gap during the COVID-19 economic crisis. In this study, we furthermore show that this is driven particularly by the income process of women living in households with middle-income levels and that have kids. These women may have experienced stronger difficulties with family conciliation but at the same time may have been more able to reduce their labor force participation relative to poorer women. Fourth, we find very large income losses for the self-employed. By May 2020, the poorest 40% of self-employed individuals had lost on average 46% of their income. While they recovered 17 points of this drop by November 2020, the magnitude of the income reduction by November 2020 is still sizable. Fifth, salaried workers also experienced large losses on their income. By May 2020, the poorest 40% of workers experienced 28% declines in income. Sixth, we find moderate declines in psychological well-being that are uniform across the income distribution. However, the reasons for loss of well-being are different across deciles: while richer individuals are more concerned about loss of contact with dear ones, the poor are more concerned about loss of income and employment as an important source of distress.

Overall, this study illustrates the importance of having access to detailed data on households finances that can be collected and processed in a timely manner. Furthermore, in contrast to other studies in the Spanish context, it defines households as the unit of analysis. Household income is likely a better measure of standards of living of a large fraction of the population, particularly in settings where some household members specializes in home production. This study also contributes to the literature by documenting the psychological effects of the crisis generated by the COVID-19 pandemic. The use of online surveys allows researchers to collect these additional metrics of well-being which are not available in administrative data or surveys from official sources.

Notes

Note that in terms of labor market outcomes, the Spanish Labor Force Survey (EPA) is timely published quarterly. These data provide information on a large sample of individuals representative at the national level. However, they do not contain overall earnings, income, or information on household characteristics or economic situation. Hence, it is not well suited to provide a comprehensive measure of income inequality for the Spanish population.

Financial Times., Covid: why Spain is hit worse than the rest of Europe, Sept 2020.

The survey question referred to total income. Hence, it may include earnings from labor and capital earnings, as well as government transfers and other types of income. See Sect. 2 for details.

The magnitudes of the earning losses in the USA and the UK are similar to the ones we estimate for Spain, ranging from around 30% for poorer individuals to around 10% for the more affluent. The drop is around 1/3 smaller in Germany across the whole distribution. Two caveats to interpret these difference are that Adams-Prassl et al. (2020) focus on individuals that had done some paid work in the past 12 months, while we study the whole adult population and that their outcomes are measured in March, while ours are in May (and November).

For the case of Spain the estimated Gini coefficient takes values of 0.339 in January 2020, 0.345 in May 2020, and 0.323 in September 2020.

GDP per capita dropped by 5.9% between the fourth trimester of 2019 and the second trimester of 2020, and the unemployment rate grew from 13.78 to 15.33% in this period. The change in GDP between the last trimester of 2019 and the last trimester of 2020 was \(-9.9\)%. Source: INE. Source 1, Source 2.

The field work for the first wave started in June and lasted until early July 2020. 93% of respondents submitted the questionnaire in June and 7% of them in July. The field work for the second wave started in late-November and finished during December. 16% of respondents submitted the questionnaire in November and 84% in December.

CIVIO - Description of Essential Activities during the State of Alarm.

COVID-19 Status Report 123, June 2020, Spanish Health Ministry.

COVID-19 Status Report 261, November 2020, Spanish Health Ministry.

Only the measures of well-being were collected after the experimental part. However, the results presented in this paper are similar if we control for the effects of the experiments. The experiment in the first wave provided information treatments about the severity of the economic crisis and the policy response to a randomly selected treatment group. In the second wave, we provided information on the management of the COVID response across different regions.

This is achieved through a quota-sampling system. The population is first segmented into mutually exclusive subgroups of age, gender, region, and education level. Then, individuals are contacted from Yougov’s panel of respondents until all quotas are filled.

The first wave of our study sampled 5051 individuals that were all recontacted during the second wave. Of them, 3297 completed the questionnaire in the second wave. From this sample we dropped 619 individuals because they did not report complete information on income, occupation, or well-being.

These regions correspond to Nielsen areas, which are frequently used by data analytics firms.

In Appendix Table 3, we evaluate how well our sample matches inequality measures and, more generally, the income distribution of the Spanish population according to EU-SILC, the European armonized household survey. The Spain this survey is also known as Living Conditions Survey (Encuesta de Condiciones de Vida). For the year 2019, the Gini coefficient measured in EU-SILC is 33, while it is 36 in our sample. The income deciles are similarly distributed, albeit our measured incomes are lower in levels relative to the data from EU-SILC.

Specifically, weights are computed by Yougov using the random iterative method, calibrated to the marginal distributions of age, gender, region, and education level of the population according to 2019 National Institute of Statistics (INE) data.

We infer years of education from education categories. We used the following correspondence to years of education: primary schooling or less = 5, secondary education = 10, upper secondary (ESO) = 12, vocational training (FP) =10, higher education = 16.

Note that our measure of income may include both labor and capital income. In particular, earnings from professional activities may include earnings from self employment or from business profits. However, returns from capital are likely to represent a small fraction of household total income, except for those in the very top income deciles.

We defined narrow intervals in order to have high precision in their self-reported income. The intervals offered are the following (all expressed in € per month): 0, 0–300, 300–600, 601–900, 901–1200, 1201–1500, 1501–1800, 1801–2100, 2101–2300, 2401–3000, 3001–4500, 4501–6000, more than 6000. We consider 8000€ as the proxy of income for the highest interval. Few individuals select the largest income bracket. Hence, the precise income estimate for the top income bracket will not have a large effect on our results.

The intervals provided were the following (all expressed in € per month): reduced by more than 1000, reduced between 600 and 1000, reduced between 400 and 600, reduced between 200 and 400, reduced between 100 and 200, stayed the same, increased by 100–500, increased by more than 500.

In some instances the reported 2019 income-level differs between the first and second wave. This is natural since we did not ask for income levels for a specific month of 2019, but for the “average month”. To calculate the percent income changes, we divide the reported change in income by the level of income in 2019, as reported in the same survey. This is the most natural option, since respondents probably had in mind the reported 2019 income level when answered to the change in incomes between the start of the pandemic and the current moment. Furthermore, we winsorize changes in income by replacing income changes higher than 100% by that number. This imputation is done for 53 observations.

Source: INE. National Income Statistics.

In the first wave, respondents could also choose mobility restrictions, which were not an issue during the second wave. 50% of respondents selected this option.

In Appendix Fig. 11, we represent the Lorenz curve and its evolution during this period.

Source: World Bank Data.

See Appendix Table 4 for additional measures of inequality estimated using our data.

See, however, Bell et al. (2021) for an study that finds greater income losses for men than for women.

Note that including additional dummies for the other income quintiles does not change the main take-away of the results and makes the presentation slightly more cumbersome.

Note that individuals that were unemployed shortly before the pandemic may have been employed during 2019. Hence, there are multiple reasons why they may have experienced changes in income, from changes in labor income, changes in their unemployment subsidies, or changes in the earnings from the informal economy. Our income question was comprehensive by design in order to incorporate multiple sources of income and provide a good proxy for cash-at-hand of individuals.

See Sect. 2 for a description of “essential” economic activities and its implications.

Record of Temporary Employment Regulation.

Record of Temporary Employment Regulation .

Record of Temporary Employment Regulation.

Record of Temporary Employment Regulation.

Record of Temporary Employment Regulation.

Record of Temporary Employment Regulation.

x refers to the number of contact tracers per 100,000 inhabitants corresponding to the autonomous community of the respondent, according to the answer to question 3. t refers to the number of contact tracers per 100,000 inhabitants that would be necessary to track all cases.

Record of Temporary Employment Regulation.

x refers to the number of contact tracers per 100,000 inhabitants corresponding to the autonomous community of the respondent, according to the answer to question 3. t refers to the number of contact tracers per 100,000 inhabitants that would be necessary to track all cases.

References

Adams-Prassl A, Boneva T, Golin M, Rauh C (2020) Inequality in the impact of the coronavirus shock: evidence from real time surveys. J Public Econ 189:104245

Alon T, Coskun S, Doepke M, Koll D, Tertilt M (2021) From mancession to shecession: women’s employment in regular and pandemic recessions. NBER Working Paper No. 28632

Aspachs O, Durante R, Graziano A, Mestres J, Montalvo JG, Reynal-Querol M (2020) Real-time inequality and the welfare state in motion: evidence from COVID-19 in Spain [Economics Working Papers]. 1734

Banco de España (2021) Informe anual 2020. Informe Anual

Bell BD, Bloom N, Blundell J (2021) This time is not so different: income dynamics during the Covid-19 recession. NBER Working Paper No. 28871

Bentolila S, Cahuc P, Dolado JJ, Le Barbanchon T (2012) Two-tier labour markets in the great recession: France versus Spain. Econ J 122(562):155–187

Bonhomme S, Hospido L (2017) The cycle of earnings inequality: evidence from Spanish social security data. Econ J 127(603):1244–1278

Chetty R, Friedman JN, Hendren N, Stepner M et al (2020) Real-time economics: a new platform to track the impacts of COVID-19 on people, businesses, and communities using private sector data. NBER Working Paper 27431

Clark A, D’Ambrosio C, Lepinteur A (2020) The fall in income inequality during COVID-19 in five European countries. Working Paper 565, ECINEQ, Society for the Study of Economic Inequality

Ettman CK, Abdalla SM, Cohen GH, Sampson L, Vivier PM, Galea S (2020) Prevalence of depression symptoms in US adults before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open 3(9):e2019686–e2019686

Farre L, Fawaz Y, Gonzalez L, Graves J (2020) How the COVID-19 lockdown affected gender inequality in paid and unpaid work in Spain. IZA DP No. 13434

Foremny D, Sorribas-Navarro P, Vall-Castelló J (2021) Mental health and inequality in pandemic times: the impact of occupations across gender, age, and income groups. Unpublished Manuscript

Piketty T, Saez E, Zucman G (2018) Distributional national accounts: methods and estimates for the United States. Q J Econ 133(2):553–609

Stantcheva S (2021) Inequalities in the times of a pandemic. Mimeo

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Funding

This study was funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation Grants (ERC2018092849 and PID2020120596GBI00) and the Maria de Maeztu Exploration Grant (MDM-2016-0684).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The data collection and survey experiment received ethics clearance from CEMFI (Centro de Estudios Monetarios y Financieros)?s IRB (Application References \(\#8\) and \(\#9\); Approval dates: June and October 2020).

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

We thank Manuel Arellano, Samuel Bentolila, Nezih Guner, Laura Hospido, Diego Puga, Ernesto Villanueva, and seminar participants at CEMFI and Banco de España for valuable comments and suggestions. Cristian Navarro, Sancho Pérez, Qianqian Shang, and Daniela Solá provided outstanding research assistance. We thank financial support for this project from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation grants (ERC2018092849 and PID2020120596GBI00) and the Maria de Maeztu Exploration Grant (MDM-2016-0684). The opinions and analyses are the responsibility of the authors and, therefore, do not necessarily coincide with those of the Banco de España or the Eurosystem.

Appendices

A Appendix Figures

Incidence of job loss by gender (May 2020). Notes: This figure shows the fraction of respondents by job status in May 2020 by gender and income group. Group 1 contains the poorest quintiles, group 2 contains quintiles 2 and 3 and group 3 contains quintiles 4 and 5. The sample is restricted to salaried workers

B Appendix Tables

See Tables 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 and 15.

C First-Wave Questionnaire

Answer options are in italic, separated by a semicolon.

-

1.

Please, enter your year of birth.

-

2.

You are a...

Man; Woman

-

3.

The following questionnaire aims to collect information on the effects of Covid-19 on the household economy. Your participation is voluntary, completely anonymous, and you can leave the survey at any time. We will ask you a series of questions about your personal and economic situation. We will also give you information that you may find useful about some recent changes in our society.

The results of this survey will be used by a team of researchers from the Center for Monetary and Financial Studies and other academic institutions for scientific purposes only.

-

4.

Do you agree to participate?

Yes; No

1.1 C.0.1 Basic demographic information

-

5.

In which autonomous community do you live?

Andalucía; Aragón; Cantabria; Castilla y León; Castilla-La Mancha; Cataluña; Ceuta; Comunidad de Madrid; Comunidad Foral de Navarra; Comunidad Valenciana; Extremadura; Galicia; Islas Baleares; Islas Canarias; La Rioja; Melilla; País Vasco; Principado de Asturias; Región de Murcia

-

6.

In which province do you live?

A Coruña; Alacant/Alicante; Álava; Albacete; Almería; Asturias; Ávila; Badajoz; Barcelona; Burgos; Cáceres; Cádiz; Cantabria; Castelló/Castellón; Ciudad Real; Córdoba; Cuenca; Girona; Granada; Guadalajara; Guipúzcoa; Huelva; Huesca; Islas Baleares; Jaén; La Rioja; Las Palmas; León; Lleida; Lugo; Madrid; Málaga; Murcia; Navarra; Ourense; Palencia; Pontevedra; Salamanca; Santa Cruz de Tenerife; Segovia; Sevilla; Soria; Tarragona; Teruel; Toledo; Valencia; Valladolid; Vizcaya; Zamora; Zaragoza

-

7.

What is the highest educational or work qualification you have?

No studies at all; Primary education; First stage of Secondary Education (ESO); Second stage of Secondary Education (Bachillerato); Vocational education (Intermediate Level); Vocational education (Advanced Level); Incomplete university studies; University Studies (Diploma); University Studies (Bachelor’s Degree); Master’s Degree; PhD; Other; I prefer not to answer

[If the respondent answers something different to “Other”, go to question 9.]

-

8.

Could you please specify what is the highest educational or work qualification you have?

Text box

-

9.

How many people, including yourself, live in your household? Please, indicate the number of people for each of the following age groups:

-

Minors (0 to 17 years old)

-

Adults (18 to 64 years old)

-

Adults (65+ years old)

Text box (one for each age group)

-

-

10.

What is your nationality?

Spanish; Other (please specify)

[If the respondent answers “Spanish”, go to question 6.]

-

11.

How many years have you been legally resident in Spain, if any?

I do not have legal residence; Less than 1 year; 1 to 5 years; More than 5 years; I prefer not to answer

1.2 C.0.2 Employment situation

Employment situation before the state of alarm (March 1, 2020)

-

12.

Which of the following options best represents your employment status before the state of alarm (this is, before March 1, 2020)?

Employee (private sector); Employee (public sector); Entrepreneur, professional or self-employed; Retiree or pensioner; Unemployed but I have worked before; Unemployed and I have not worked before; Student; Unpaid domestic work; Other (please specify)

[If the respondent answers “Unemployed but I have worked before”, go to question 13. If the respondent answers“Employee (private sector)”, “Employee (public sector)” or “Entrepreneur, professional or self-employed”, go to question 14. Otherwise, go to question 10.]

-

13.

You indicated that you were unemployed before the state of alarm, but that you have worked before. Please, indicate the date on which your last employment contract ended. Please, use the following format: DD/MM/YYYYY (Day/Month/Year). For example: 04/17/2008.

Text box

-

14.

What type of occupation or position best reflects your work activity before the state of alarm (this is, March 1, 2020)?

Directors and managers; Professionals, scientists and intellectuals; Technicians and associate professionals; Clerical support workers; Service personnel in the hotel, tourism and catering industry; Service personnel in other sectors; Domestic service; Sales workers; Delivery men and women; Security personnel; Cleaning personnel; Agricultural workers; Officers, and craft and related trades workers; Plant and machine operators, and assemblers; Healthcare personnel (doctors or managers); Healthcare personnel (nurses or assistants); Healthcare personnel (other); Military and police occupations; Other (please specify); I do not know

-

15.

What type of contract or occupation best reflects your situation before the state of alarm (this is, March 1, 2020)?

Salaried employee with indefinite contract (full time); Salaried employee with indefinite contract (part-time); Salaried employee with temporary contract (full time); Salaried employee with temporary contract (part-time); Entrepreneur or professional with employees; Professional or self-employed with no employees; Household chores; Other situation (please specify)

-

16.

What was the main activity of the company or organization where you were employed before the state of alarm (this is, March 1, 2020)?

Agriculture, livestock and primary sector; Extractive industries; Manufacturing industry; Power, gas and water production and distribution; Construction; Retail trade, repair of vehicles and objects; Hotels, tourism, catering; Transportation, warehousing and communications; Financial services; Consulting, advertising or other business services; Real estate activities; Public service; Security and defense services; Education; Health and veterinary services, social services; Culture and sports; Other activities (please specify)

[If the respondent answered “Employee (private sector)”, “Employee (public sector)” or “Entrepreneur, professional or self-employed” to question 6, go to question 17. If the respondent answered “Unemployed but I have worked before” to question 6, go to question 10.]

Employment situation during the state of alarm

-

17.

Was your job declared “essential” during the state of alarm?

Yes; No; I do not know

-

18.

How did your work situation change as a result of the declaration of the state of alarm on March 14?

I continued to work in the same job or occupation; I was included in an ERTEFootnote 33; I stopped working when I was laid off or my employment contract ended; I changed my job or started a new job or occupation; Other (please specify)

[If the respondent answers “I continued to work in the same job or occupation”, go to question 19. If the respondent answers “I was included in an ERTE\(^{33}\)”, go to question 21. If the respondent answers “I stopped working when I was laid off or my employment contract ended”, go to question 23. If the respondent answers “I changed my job or started a new job or occupation”, go to question 24. If the respondent answers “Other (please specify)”, go to question 10.]

-

19.

How has the length of your working day changed?

I work as many hours as before; I work fewer hours than before; I work more hours than before

-

20.

How has the nature of your working day changed?

I still work onsite the whole working day; I have switched to teleworking partially; I have switched to teleworking fully; I keep teleworking part or all of my working day, as I already used to do before; Other (please specify)

[Go to question 10]

-

21.

Are you still in ERTEFootnote 34 situation?

Yes; No

[If the respondent answers “Yes”, go to question 10.]

-

22.

You indicated that you are no longer in ERTE\(^34\) situation. Please, indicate approximately the date in which this situation ended in your job.

Text box

[Go to question 10.]

-

23.

Have you found a new job?

Yes; No

[If the respondent answers “No”, go to question 10.]

Employment situation in case of change during the state of alarm

-

24.

You indicated that you changed your job or started a new job or occupation after the state of alarm was declared. Could you please indicate which of the following options best represents such new job/occupation?

Employee (private sector); Employee (public sector); Entrepreneur, professional or self-employed; Retiree or pensioner; Student; Unpaid domestic work; Other (please specify)

[If the respondent answers “Retiree or pensioner”, “Student”, “Unpaid domestic work” or “Other (please specify)”, go to question 10.]

-

25.

What type of occupation or position best reflects the work activity you started during the state of alarm?

Directors and managers; Professionals, scientists and intellectuals; Technicians and associate professionals; Clerical support workers; Service personnel in the hotel, tourism and catering industry; Service personnel in other sectors; Domestic service; Sales workers; Delivery men and women; Security personnel; Cleaning personnel; Agricultural workers; Officers, and craft and related trades workers; Plant and machine operators, and assemblers; Healthcare personnel (doctors or managers); Healthcare personnel (nurses or assistants); Healthcare personnel (other); Military and police occupations; Other (please specify); I do not know

-

26.

What type of contract or occupation best reflects the new working activity you started during the state of alarm?

Salaried employee with indefinite contract (full time); Salaried employee with indefinite contract (part-time); Salaried employee with temporary contract (full time); Salaried employee with temporary contract (part-time); Entrepreneur or professional with employees; Professional or self-employed with no employees; Household chores; Other situation (please specify)

-

27.

What is the main activity of the company or organization where you started working during the state of alarm?

Agriculture, livestock and primary sector; Extractive industries; Manufacturing industry; Power, gas and water production and distribution; Construction; Retail trade, repair of vehicles and objects; Hotels, tourism, catering; Transportation, warehousing and communications; Financial services; Consulting, advertising or other business services; Real estate activities; Public service; Security and defense services; Education; Health and veterinary services, social services; Culture and sports; Other activities (please specify)

-

28.

Was your job declared “essential” during the state of alarm?

Yes; No; I do not know

-

29.

Has your work situation undergone any change between the last occupation you described and your current situation?

Yes; No

[If the respondent answers “No”, go to question 10.]

Current employment situation

-

30.

You indicated that your employment situation changed between the last occupation you described and your current situation. Could you indicate what was this change in your employment situation?

I changed my job or started a new job or occupation; I was laid off or my employment contract ended, and now I am unemployed; I was laid off but I have found a new job; I was included in an ERTEFootnote 35; Other (please specify)

[If the respondent answers “I was laid off or my employment contract ended, and now I am unemployed”, “I was included in an ERTE\(^35\)” or “Other (please specify)”, go to question 10.]

-

31.

Which of the following options best represents your current employment status?

Employee (private sector); Employee (public sector); Entrepreneur, professional or self-employed; Retiree or pensioner; Student; Unpaid domestic work; Other (please specify)

[If the respondent answers “Retiree or pensioner”, “Student”, “Unpaid domestic work” or “Other (please specify)”, go to question 10.]

-

32.

What type of occupation or position best reflects your current work activity?

Directors and managers; Professionals, scientists and intellectuals; Technicians and associate professionals; Clerical support workers; Service personnel in the hotel, tourism and catering industry; Service personnel in other sectors; Domestic service; Sales workers; Delivery men and women; Security personnel; Cleaning personnel; Agricultural workers; Officers, and craft and related trades workers; Plant and machine operators, and assemblers; Healthcare personnel (doctors or managers); Healthcare personnel (nurses or assistants); Healthcare personnel (other); Military and police occupations; Other (please specify); I do not know

-

33.

What type of contract or occupation best reflects your current situation?

Salaried employee with indefinite contract (full time); Salaried employee with indefinite contract (part-time); Salaried employee with temporary contract (full time); Salaried employee with temporary contract (part-time); Entrepreneur or professional with employees; Professional or self-employed with no employees; Household chores; Other situation (please specify)

-

34.

What is the main activity of the company or organization where you currently work?

Agriculture, livestock and primary sector; Extractive industries; Manufacturing industry; Power, gas and water production and distribution; Construction; Retail trade, repair of vehicles and objects; Hotels, tourism, catering; Transportation, warehousing and communications; Financial services; Consulting, advertising or other business services; Real estate activities; Public service; Security and defense services; Education; Health and veterinary services, social services; Culture and sports; Other activities (please specify)

1.2.1 Individual and household income

-

35.

What was your monthly income, on average, during 2019? Please specify both:

-

Your individual monthly income

-

That of your household as a whole

By income we mean, for example, wages, income from professional activities, pensions and subsidies, among others. Please indicate the net income, this is, your income after taxes. You do not need to indicate the exact amount, just need to indicate in which interval of the following scale are included your income and the income of your household. We remind you that this information is completely confidential.

I have no income at all; 0–300€; 301–600€; 601–900€; 901–1200€; 1201–1500€; 1501–1800€; 1801–2100€; 2101–2400€; 2401–3000€; 3001–4500€; 4501–6000€; 6000€+; I do not know / I prefer not to answer

-

-

36.

Thinking about your net monthly income, did it changed during the first weeks of the state of alarm (this is, between March 15 and May 31, 2020)? Please, specify this for:

-

Your individual monthly income

-

That of your household as a whole

Yes; No

-

-

37.

And, more precisely, how has your net monthly income (after taxes) changed between March 15 and May 31, 2020? Please, specify this for:

-

Your individual monthly income

-

That of your household as a whole

Reduced by more than 1000€ per month; Reduced between 600€ and 1000€ per month; Reduced between 400€ and 600€ per month; Reduced between 200 and 400€ euros per month; Reduced between 100 and 200€ euros per month; It is more or less the same; Increased between 100 and 500€ per month; Increased by more than 500€ per month; I do not know; I prefer not to answer

-

-

38.

Have you received any public subsidy, aid or benefit during the last 6 months? Check all that apply: