Abstract

The Spanish debt consolidation between 1996 and 2007 represents, by its size and duration, an impressive case among the European Union countries. This paper aims at characterizing the Spanish debt consolidation process in order to assess its effects on economic inequality and welfare. For that purpose we built a general equilibrium heterogeneous-agent model capable of exploring the relationship between fiscal policy variables and the endogenous cross-section distribution of income and wealth. The results show a quite impressive positive welfare gain despite significant transition costs. The simulations point to an increase of inequality during the initial transition period, reversing to more compressed distributions as the economy evolves to its final steady state equilibrium. Overall, the welfare gains are slightly biased towards wealthier individuals. Furthermore empirical data on the dynamics of some crucial variables during the consolidation period lend support to the model simulation results.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The history of the Spanish public administration differs from most of the other western European economies, mainly due to the late establishment of a modern democratic regime based on free elections and on the market-based economy system.Footnote 1 From this point of view, Spain’s recent experience is similar to other two Mediterranean countries: Portugal and Greece.

The recent evolution of the Spanish public finances can be divided in two periods, before and after the establishment of democracy. During the dictatorship of Franco, public expenditure grew slowly but steadily, impelled by the 1959 Stabilization Plan, which was a first attempt to open and liberalize the Spanish economy.Footnote 2 Concerning the structure of expenditure growth, the major effort was related to public infrastructures and to the development of a social security system. This period was also characterized by strong economic growth (interrupted in 1973 with the first oil shock) and balanced budgets which led to a public debt-to-output-ratio of \(12.5~\%\) in 1974.

Throughout the democratic period, we can distinguish two phases. The first phase between 1975 and 1985, corresponds to the development and consolidation of the welfare state. The second phase begins with a first period of fiscal consolidation initiated with the CEE membership in 1985 and interrupted by the economic and social crisis in the beginning of the 1990s, and proceeds with a second fiscal consolidation process (1996–2007) which is focused in our paper. Between 1975 and 1985, during the transition to democracy, total public expenditure almost doubled from 23.5 to 41.6 %, and public debt reached 43.7 % of GDP. The climb resulted from a succession of strong deficits, low economic growth and also from the creation of the 17 autonomous regions and the corresponding decentralization of a significant part of the public expenditure.Footnote 3 The first period of debt consolidation (1986–1988) was mostly revenue-based and led to a small reduction of the debt-to-output ratio. However, this fiscal adjustment period ended by 1989, due, first, to the incapacity of government to sustain the growing trend of expenditure resulting from strong social protests and, second, to the economic crisis in the beginning of the 1990s. Budget deficit peaked at 7 % of GDP in 1993 and the debt-to-output ratio reached 66.82 % of GDP in 1996. The second period of consolidation (1996–2007), by its size and duration, represents an impressive case among the European Union (UE) countries. After a consolidation attempt in 1992, aborted in 1993, and having as horizon the European and Monetary Union membership, the Spanish authorities entailed an ambitious plan of reforms based on several structural aspects, namely a containment of social expenditure (by tightening eligibility criteria for several social benefit such as unemployment and sickness compensation, among others), a reduction of the wage bill while maintaining high levels of public investment together with the implementation of legal and institutional changes aiming at higher budgetary discipline (European-Commission 2007). This effort has also benefited from a favorable macroeconomic environment with high growth rates and a significant drop in interest rates.

This paper aims at characterizing the debt consolidation processes put forward by the Spanish authorities between 1996 and 2007, in order to assess welfare and, in particular, the inequality effects involved. For that we built a general equilibrium heterogeneous-agent model capable of exploring the relationship between fiscal policy variables and the endogenous cross-section distribution of income and wealth.

We use a dynastic heterogeneous-agent model that includes a continuum of infinitely-lived rational agents who are hit by idiosyncratic wage shocks in an incomplete capital market, following seminal works by Bewley (1983), Imrohoroglu (1989), Huggett (1993) and Aiyagari (1995), among others. The model, based on Aiyagari and McGrattan (1998) and Floden (2001), includes government and the corresponding dynamic budget constraint. Besides including taxes levied on labour and capital, we additionally decompose government expenditure into transfers to private sector, and productive and unproductive spending. While productive expenditure is included in the production function and, through this channel, increases the global productivity of the economy, unproductive spending is only utility-augmenting. The model also includes optimizing firms endowed with a neoclassical Cobb-Douglas production function and optimizing households that accumulate savings during “good times” while spending them during “bad times”.

The analysis of a debt consolidation process requires a transition between two steady states. Thus, besides steady-state analysis, transition paths are crucial for the computation of welfare effects and inequality. In order to simulate the transition paths imposed by a debt consolidation strategy, we follow the methodology of Rios-Rull (1999) and Mendoza et al. (2009). The simulations are conducted under an open economy framework, assuming the existence of a global market for assets and, hence, a common interest rate. This international mobility of capital implies that each country may have either a positive, negative or balanced foreign asset position.

Collecting Spanish data from the AMECO database, we apply the criteria proposed by Alesina and Perotti (1995) in order to detect the successful debt consolidation processes between 1990 and 2010. Secondly, consolidation episodes are identified as active if a permanent debt reduction results mainly from the control of the cyclically-adjusted primary deficit. Third, we further analyze the composition of the cyclically-adjusted primary deficit in order to detect the main sources of consolidation. Fourth and finally, we use our model to mimic the Spanish consolidation processes while assessing the welfare and inequality costs involved.

The paper is organized as follows. The Spanish consolidation strategies are analyzed in Sect. 2. In Sect. 3 we describe the model, and define the social (aggregate) welfare metric. We proceed with the simulations and discuss the main results in Sect. 4, and conclusions are drawn in Sect. 5.

2 Identification of the consolidation strategies

In order to characterize debt consolidation processes in Spain, we proceed following the approach in the seminal paper by Alesina and Perotti (1995) which identifies “significant fiscal impulses” in OECD countries between 1960 and 1992, in order to study the determinants of “successful” budget consolidation processes. In particular, they define “significant” changes in fiscal policy stance using a cyclically adjusted measure of government primary balance and set several cut-off points. Moreover, a fiscal adjustment in year t is defined as “successful” if the gross debt/GDP ratio in year \(t+3\) is at least 5 % points lower than in year t.

In our approach, we apply the criteria used by Alesina and Perotti (1995), but proceed backwards to detect all episodes of “successful” debt consolidation in Spain between 1990 and 2010. We start by identifying the periods where debt-to-output ratios are, at least, 5 % points below the value observed 3 years before. Then, we proceed with identifying the determinants leading to such positive debt dynamics - cyclically adjusted primary deficit, snow-ball and stock-flow adjustments (for more details on the definitions, see European-Commission 2009). Consolidation episodes are identified as active if the reduction in the cyclically-adjusted primary deficit dominates. We further analyze the budget composition in order to detect the main sources of primary balance adjustment. Finally, we use our model to mimic each consolidation process while assessing the welfare costs involved.

Figure 1 shows the Spanish debt dynamics. The light columns show the debt level ant the dark columns show the debt variation (\(d_{t}-d_{t-3}\)). From 1990 to 2010, we identify nine successive episodes in which the successful criteria verifies, starting at 1996 and ending in 2007. From 1996 to 2007, the debt-to-output ratio decreased from 66.82 to 36.24 %.

Debt dynamics: Spain (1990–2010). SourceEuropean-Commission (2009) and AMECO database

In order to extract (active) fiscal consolidation processes, we decompose debt dynamics as usual (see, among others, European-Commission 2009):

where, D stands for government debt, \({\textit{PD}}\) for general government primary deficit, \({\textit{SF}}\) for the stock-flow adjustment and i for nominal interest rate paid by the government.

Equation (2.1) can be re-written in terms of debt-to-output dynamics as:

where \(Y^n\) is \({\textit{GDP}}\) at current market prices and n stands for the corresponding growth rate. The first term of the right part in Eq. 2.2 refers to the snow-ball effect (SB).

Different contribution to debt reduction: Spain (1996–2007). Source European-Commission (2009) and AMECO database

Figure 2 shows, for the whole period, the debt decomposition into primary deficit (PD), snow-ball (SB) and stock-flow adjustments (SFA) as presented in Eq. 2.2, but distinguishing between cyclically adjusted and cyclical components of primary deficit. Table 1 presents the cumulative values of each effects (in % of GDP, including the cyclical (PD(cycle)), and cyclically-adjusted (PD(adj)) components of primary deficit) for the whole consolidation period. During the study period, Spain has enjoyed a good economic conjuncture with high economic growth and low interest rates. In this sense, Domingo et al. (2014) document the importance of the fiscal effort of the government, giving ample emphasis to a combination of economic growth, low interest rate and inflation. Accordingly, our results show that snow-ball effects associated with the cyclical component of primary deficit are responsible by a cumulative debt reduction of 18.04 % points. Still, according to the same data presented in Table 1, we can identify the Spanish fiscal adjustment as an active consolidation process, since debt reduction process was also driven by the control over the cyclically-adjusted primary deficit. For a debt-to-output reduction of 31.18 % points, the cyclically-adjusted primary deficit accounts for a reduction of 19.38 % points.Footnote 4 Finally, stock-flow adjustments are responsible for an increase of debt of 6.24 % points.

Spanish cyclically-adjusted primary deficit components (% of GDP): tax burden and final consumption (left-hand scale); social transfer other than in kind and gross fixed capital formation (right-hand scale). SourceEuropean-Commission (2009) and AMECO database

To characterize the cyclically-adjusted budget deficit reduction, the model considers a single instrument on the revenue side, the tax burden, and three instruments on the expenditure side: final consumption, social transfers other than in kind and gross capital formation, as in European-Commission (2009). Figure 3 exhibits accordingly the cyclically-adjusted actual evolution of each of the four fiscal instruments. Spending was adjusted for the cyclical component by applying the elasticity of total expenditure (excluding interest rate) relative to the cycle to all items. Similarly, for the tax burden, we used the total government revenue elasticity. Elasticities were calculated from the AMECO Database series. During the whole consolidation process, we can see a decrease in social transfers, along with a slight increase in public investment. On the other side, the tax burden increased especially during the second-half part of the adjustment. Table 2 summarizes the initial (1996) and final (2007) values (% GDP) for each of the cyclically-adjusted primary deficit components and for the debt-to-output ratio.

Summing up, and according to the data in Fig. 3 and Table 2, the Spanish consolidation is identified as a mixed strategy based on taxes (especially during the second half period) and a reallocation of social transfer towards public investment expenditure.

3 Model

The model is built from a standard growth model modified to include a role for government together with an uninsured idiosyncratic risk and liquidity/ borrowing constraints. We rely on the original models of Aiyagari and McGrattan (1998) and Floden (2001) modified to break government expenditure into productive and unproductive. While the former is taken to be utility augmenting through inclusion in the utility function, the productive expenditure is considered as input to the production function. We also use a different approach for the calibration of the idiosyncratic shock.

We set up an open economy framework composed by two countries or regions, indexed by i. Both blocks are identical except for the size and for the path of the fiscal policy instruments. Capital flows freely across borders while labour, instead, is assumed not to flow across countries. We take Spain as the domestic block, with a corresponding weight measured by the Spanish GDP over the EU15 GDP, p. Likewise, the foreign (“rest of the world”) block, with weight (\(1-p\)), includes all the other EU15 countries (EU15-1) and is assumed to act passively to the debt reduction process in Spain.

Each country/region is populated by a continuum of infinitely-lived agents of unit mass who receive after-tax wage payments, w, after-tax interest from savings, \(\overline{r}a\), and transfers, tr, from the government. Following Barro (1973) and Floden (2001, 2003), we consider that, besides private consumption, c, and leisure, l, unproductive government spending, \(g_u\), also contributes to households’ utility at decreasing returns depending on a parameter, \(\vartheta \). In each period, agents are hit by idiosyncratic shocks, \(e_t\) , which determines the productivity level. Borrowing is allowed only up to a certain limit b and complete capital markets are ruled out. This implies that agents have to ensure themselves by saving during “good times” (\(a_{t+1}-a_t>0\)) while, during “bad times”, savings are negative (\(a_{t+1}-a_t<0\)). Each agent is endowed with one unit of time and solves the double problem of choosing between labor and leisure, and between consumption and saving in order to maximize expected lifetime utility:

Subject to the following budget constraint:

The household’s instant utility functions are specified as:

where \(\mu \) represents the degree of risk aversion, \(\zeta \) is constant related to average labor supply, and \(\frac{1}{\gamma }\) represents the labor supply elasticity, and

The productivity shock, \(e_t\), is an idiosyncratic shock that evolves stochastically over time according to the following process: the natural logarithm of \(e_t\) is represented by an AR(1) process with a serial correlation coefficient \(\rho \) and a standard deviation \(\sigma \):

Firms are characterized by a neoclassic production function. Output in each country, Y, is produced using capital, K, labour, N, and productive government spending, \(G_p\).

Productive government spending is identified with the share of public gross investment on output, in line with Barro (1990) and Aschauer (1989), and enters as an input to private production.Footnote 5

The parameters \(\alpha \) and \(\eta \) represent, respectively, the output elasticities relative to private capital and to productive government expenditure. The production function exhibits constant returns to scale over private inputs but increasing returns over all inputs. Assuming competitive markets of goods and inputs, private factors are paid according to their marginal productivity and output is exhaustively distributed. Thus:

where \(\tau \) is a proportional income tax rate levied in each country on labour and capital and \(\delta \) is the depreciation rate of capital. We must point that the pre-tax level of interest rate, r, is fixed in the international capital market.

Government promotes both productive and unproductive expenditures, collects taxes and pays lump-sum transfers to households, facing the following budget constraint in real terms:

where, \(g_{pt}\), \(k_t\) and \(d_t\) represent respectively, public gross investment (productive expenditure), private capital and government debt as a percentage of output.

Finally, expression (3.10) represents the international asset market clearing condition when the output-weighed sum of aggregate asset holdings in each country i, \(\overline{a}^i\), equals the output-weighed sum of private capital demand plus public debt of both countries (domestic country together with “the rest of the world” block). As before, all variables are expressed as a percentage of output.

3.1 General equilibrium definition

Consider \(\{r^i_t, w^i_t\}_{t=0}^{\infty }\) a deterministic sequence of prices (interest rate and wage) and \(\{d^i_t, g^i_{ut}, g^i_{pt}, tr^i_t\}_{t=0}^{\infty }\) an exogenous sequence of government policy in each region i. The problem of the agent in a recursive form can be written as:

The solution to the agent’s problem of each country delivers all agents decision rules, namely for consumption, \(c^i_t (e_t,a_t)\), leisure, \(l^i_t(e_t,a_t)\), and savings, \(a^i_{t+1}(e_t,a_t)\). These decision rules determine the evolution of the distribution of wealth over e and a, denoted by \(\lambda _t(e,a)\).

As such, given an initial steady state characterized by a vector of equilibrium prices, \(\{r_0,w^i_0\}\), and a stationary distribution, \(\lambda ^i_0(a,e)\) and a sequence of government policy \(\{d^i_t, g^i_{ut}, g^i_{pt}, tr^i_t\}_{t=0}^{\infty }\) for each country/region i, the general equilibrium is defined by sequences of: (i) agents decisions, \(\{c^i_t(a_t,e_t),\) \( l^i_t(a_t,e_t), a^i_{t+1}(a_t,e_t)\}_{t=0}^{\infty }\); (ii) value functions \(\{V^i_{t}(a_{t},e_{t})\}_{t=0}^{\infty }\) (iii) prices, \(\{r_t,w^i_t\}_{t=1}^{\infty }\) and (iv) distributions \(\{\lambda ^i_t(a_t, e_t)\}_{t=1}^{\infty }\). Such that (a) agent decisions solve (3.11); (b) government budget constraint is fulfilled; (c) assets and labour markets clear, \(\sum _ip_i\int a^i_t\, d\lambda ^i=\sum _ip_i(K^i_t(r)+D^i_t)\) and \(\int e_t (1-l^i_t)\, d\lambda ^i=N^i\), for all \(\{t,i\}\); and (d) the sequences of \(\lambda ^i_t(a_t, e_t)_{t=1}^{\infty }\) are consistent with the initial steady states, the agent decision rules and the idiosyncratic shock in each country i.Footnote 6

3.2 Solving the model

In order to solve the transition paths imposed by the Spanish debt consolidation strategy we closely follow Mendoza et al. (2009), Ljungqvist and Sargent (2004), Rios-Rull (1999) and Auerbach and Kotlikoff (1987). We consider a planner who inherits at time t a predetermined state vector, including initial debt-to-output ratio, and face a sequence of fiscal parameters for each period within a given horizon in order to reach a new state vector that includes a previously announced target for the debt-to-output ratio at the end of the planning period (De la Fuente 2000). As such, the trajectories of public debt and fiscal parameters (\(\{d^i_t, g^i_{ut}, g^i_{pt}, tr^i_t\}\)) in each region (Spain and “rest of world”) are fixed exogenously. Taxes adjust according to the budget constraint. The algorithm for solving the equilibrium transition path of the economy, given a particular parameterization, typically proceeds in three stages (Auerbach and Kotlikoff 1987). First we solve for the long-run initial steady state of the economy (before the implementation of the fiscal consolidation strategy). Second, we solve for the long-run steady state towards which the economy will converge after full-effects of the fiscal consolidation. The initial and final steady state and depend on parameters fixed ex-ante by the government and are calculated independently as in Viegas and Ribeiro (2013b). Third, we solve for the transition path of the economy between the two steady states.

In particular, the algorithm for running the third step follows Rios-Rull (1999) and involves the following steps: (i) choose the sequences for the common interest rate and for wages in both countries in each period of transition period \(r_t\) and \(w^i_t\) \((i=1,2)\); (ii) take the sequences \(w^i_t(i=1,2)\) and \(r_t\) and solve backwards the value functions to simulate the whole transition for the economy, updating the distributions according to agent’s decisions as to obtain sequences for aggregate asset demand and labour supply; (iii) adjust the sequences in order to clear asset and labour markets for each period of the transition path; (iv) repeat steps (ii) and (iii) until the three sequences converge and all markets clear.

3.3 Social welfare computation

The utilitarian social welfare, U, is defined as the solution of (3.1) across all households (i.e, conforming the stationary distribution):Footnote 7

Since the utility function is concave, the utilitarian social welfare is influenced by the distribution, and thus, higher inequality or uncertainty will reduce welfare. Considering a policy change that moves an economy from equilibrium A to equilibrium B, we define the welfare gain (\(w_u>0\)) or loss (\(w_u<0\)), in percentage of life-time consumption:

3.4 Calibration

Preferences \(\mu \) is set at 1.5, a value of standard use in the literature. For \(\gamma \), Floden (2001) set it to 2 which is equivalent to a wage elasticity of labour supply equal to 0.5. For Spain, Burriel et al. (2010) estimate \(\gamma =1.8\) which corresponds to a wage elasticity of labour supply around 0.56. Varga et al. (2014) also use a similar value and set \(\gamma =2.5\). The parameter \(\zeta \) is set in order to match an average labour supply of around 0.3 (\(\zeta =9.145\)). Finally, for the preferences towards public goods and services relative to private goods, the baseline calibration sets \(\vartheta =0.1\) as most of the values used in literature are rather small (see, among others, Ni 1995; Doménech and García 2002; Ganelli and Tervala 2010). Moreover this value makes the model outcomes in terms of steady-state optimal debt compatible with average European data on fiscal policy variables (see Viegas and Ribeiro 2013a).

Technology The production function is inspired in Barro (1990) to incorporate productive government spending. For our baseline model we follow Aschauer (1989) and set \(\eta =0.3\). For the capital share, Aiyagari and McGrattan (1998) and Floden (2001) set \(\alpha =0.3\).Footnote 8 We follow Fernandez and Mauro (2000) who estimate \(\alpha =0.4\) for the Spanish economy. This value is consistent with the adjusted wage share reported by the AMECO database.

Discount factor and interest rate According to our model, \(r=\frac{\alpha }{k}-\delta \). We set \(\delta =6.5~\%\) as in Hernández and Mauleón (2005). The variable k represents the capital-to-output ratio and the steady-state value is calibrated as to match the value of the capital to output ratio of Spain.Footnote 9 Thus, the steady-state value for the real interest rate yields \(4.0~\%\), in a yearly base which implies \(\beta =0.980\).

Government Governments are characterized by a set of fiscal indicators \(\{d, tr, g_u, g_p\}\). Using the AMECO database, we calibrate policy variables as to match the Spanish consolidation episodes that occurred between 1996 and 2007. Specific values were already released throughout Sect. 2.Footnote 10 For the countries weight, we set \(p=0.0787\) for Spain which represents the average Spanish output proportion in the GDP of the EU15 between 1990 and 2010 and (\(1-0.0787\)) for the rest of the EU15 countries.

Idiosyncratic shock Following the procedure of Tauchen (1986), the idiosyncratic shock is replicated as a first order Markov chain specification with seven states to match a first order autoregressive representation as followed by, among others, Aiyagari (1994). Aiyagari (1994), Aiyagari and McGrattan (1998) and Floden (2001) draw on empirical data for earnings and annual hours worked to set \(\rho \) and \(\sigma \). Due to unavailable empirical data, we follow a different procedure. Castaneda et al. (2003) calibrated the values of the shocks and the transition matrix to match some selected moments of income and wealth distribution. We set both parameters as to match the existing inequality in Spain (measured by the disposable income Gini index). According to the OECD Statistics, the disposable income Gini index varies between 0.35 and 0.31 during the period 1991–2008. Thus we set \(\rho =0.8\) and \(\sigma =0.27\) which leads to a disposable income Gini index of around 0.33.

3.5 Robustness

In order to test the robustness of our results, we considered different values for crucial parameters of the model. When agents become more risk-averse (\(\mu \)), simulations reveal a slight decrease in welfare gains. Wealth and income Gini indexes are globally lower and the improvement on both distributions becomes less expressive. A lower labor supply elasticity (\(\frac{1}{\gamma }\)) induces a marginal decrease in the welfare gain, with no significant effect on inequality. As for government unproductive spending (\(\vartheta \)), we simulate several consolidation strategies based on unproductive expenditures with different values for the \(\vartheta \) parameter. Naturally, the welfare gain increases (decreases) as \(\vartheta \) becomes lower (higher), although marginally with no effects on inequality.Footnote 11 Finally, as the productivity of public investment (\(\eta \)) increases relative to the importance of public consumption in household’s utility, the substitution of unproductive for productive spending during a consolidation process delivers higher net welfare gains.

4 Assessment of the impacts on welfare and inequality

After having identified and classified the Spanish consolidation episodes in Sect. 2, we proceed with the simulations using the model presented in Sect. 3. Debt and fiscal instruments other than taxes are adjusted to match the described consolidation process.Footnote 12 Tax rate is endogenous, adjusting to satisfy the government budget constraint. As for the “rest of the world” block, we use the average values for each fiscal variables of the EU15-1 countries for the same period.

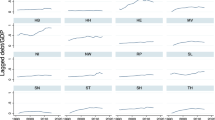

Figure 4 depicts the impulse responses of some of the main relevant macroeconomic variables to the simulated debt-consolidation effort. The dynamics of the macroeconomic and inequality variables depend strongly on the instruments used during the fiscal adjustment. As it can be seen, the tax effort implies a decrease in the after-tax wage during the initial phase, depressing the disposable income (also affected by the social transfer cuts).

Households work and save less pushing up the interest rate, which depresses the private capital level and leads to a temporary recession. In the second phase, the economy evolves towards its final steady state: interest and tax rates decrease, converging to a lower level relative to the initial steady state while disposable income, labour supply and consumption converge to higher levels.

Concerning capital flows, Fig. 5 illustrates the asset demand and supply adjustments that have occurred during the two different phases of debt consolidation. The first phase of consolidation is dominated by a significant asset demand decline leading to an excess of asset supply and, thus, a decrease in net foreign asset position. Conversely, during the second phase, the combination of an increase in disposable income together with the accrued need for insurance due to social transfers cuts, leads to a growing demand for asset holdings that ends up exceeding the initial steady state level causing an excess of asset demand, supplied by foreign assets. Capital flows outward and Spain improves its net foreign asset position.

Table 3 summarizes for the period of debt consolidation, the overall welfare gains (transition plus steady-state), the magnitude of transition costs as a percentage of final relative to initial steady-state welfare gain, the Welfare Gain Intensity (WGI) and the Total Spending Cut (TSC). The WGI refers to the welfare gain per percentage point of debt reduction while TSC measures the combined reduction in social transfers and unproductive expenditure per percentage point of debt reduction. The Spanish fiscal adjustment implies a net improvement of life-time consumption of about 20 %. Despite the recession and the rise in inequality, the net welfare gain is positive given that the increase in consumption that arises from the increase of labor income more than offset the loss of leisure. Moreover, the final distribution of wealth and income is more equitable. The transition costs represent about 25 % of the potential welfare gain.Footnote 13 These costs are strongly associated with the tax effort and the corresponding disincentive effects on savings and labour supply. The values for the welfare gain intensity (WGI) and the total spending cut (TSC) are relatively small proving that this consolidation process was of a gradual nature.

Concerning inequality, both wealth and disposable income Gini indexes increase during the first phase due to the cuts in transfer. In the second phase, as the economy evolves towards its final steady state, wealth and disposable Gini indexes decrease gradually to a final lower, steady-state levels (see Table 4). Thus, after an increase in inequality during transition, fiscal consolidation entails improvements in the distribution of both wealth and income. This effect can be explained by a mechanism operating through the labour market where the labour supply elasticity of wage is higher among the richer. With increase net wages, the substitution effect dominates for the richer, compressing the disposable income distribution. As such, the initial period is dominated by an increase income inequality due to the transfer cut, output decrease and tax increase. As the economy start to grow, the tax burden decreases, the net salary increases and income inequality tends to reduce. Also, the improved wealth distribution results from the higher marginal propensity to save of the poorer.

However, if we take a broader measure like the welfare distribution of the fiscal adjustment, results are not as favorable. Figure 6 shows the welfare gain curve (solid line) across wealth (asset holding); it also shows the initial distribution of wealth (dashed line). The slight positive slope of the welfare gain curve indicates that the richer are the ones who benefit more from the consolidation episode. Viegas and Ribeiro (2013b) have shown that the welfare distribution moves negatively with debt and positively with transfer and unproductive expenditures while productive expenditures are neutral. Decreasing social transfers as well as unproductive expenditures leads to a worse welfare distribution. Differently, debt reduction should improve the welfare distribution. Apparently, in terms of welfare inequality, transfer and unproductive spending effects have dominated over the debt effect during the Spanish consolidation process: despite debt reduction, welfare inequality across wealth increased (despite the positive welfare gain for every household).

The definition of welfare includes consumption, leisure and unproductive expenditures (public services). The global negative effect on the welfare distribution results from the dynamics of all these individual variables affecting welfare. As shown in Fig. 4, both disposable income and wealth Gini indexes present an humped shaped curve before converging to lower final levels (see, also, Table 4).

In order to make a simple test on the robustness of our results, we have collected data on actual disposable income Gini coefficient (Fig. 7) and on the net foreign asset (NFA) position (Fig. 8) for Spain, during the consolidation process. Although income distribution depends on the dynamics of multiple variables, some of which are missing from our model, the initial humped shaped curve and the afterwards downward path to a lower level relative to the initial level seem to lend support to the prediction of our model. Capital flows also depend on many other factors which the model fails to capture. Nevertheless, the downward path of NFA in Fig. 8 confirms the initial inward flow of capital and the depressed NFA position described above (see Fig. 4). However empirical data fail to replicate the second phase when capital flows out, increasing above the initial level. Thus, the actual dynamics of the Gini coefficient and the NFA position can be partially justified by the fiscal consolidation strategy.

Net Foreign Asset position: Spain. SourceLane and Milesi-Ferretti (2006)

5 Conclusion

By using a general equilibrium model with heterogeneous agents, we simulate the Spanish consolidation episode that occurred between 1996 and 2007 to assess the underlying welfare and inequality effects. We use the endogenous cross-section distribution to compute several inequality indexes and we also assess the aggregate welfare intensity measured as a percentage change of life-time consumption

Our results show a quite impressive positive net welfare gain, representing almost \(20~\%\) of life time consumption. However, the transition costs are also significant, reducing in more than \(25~\%\) the potential (gross) welfare gain. According to our simulation the final output level increases \(16.37~\%\) relative to the initial level. But the initial fiscal effort depresses strongly the economy: during the first phase, output decreases \(16.17~\%\), recovering the initial output level only after 6 years.

This upfront recession affects strongly the poorer, as it can be seen through the Gini index path. However, the wealth and disposable income distributions become more compressed as the economy moves towards the final steady state equilibrium. Summing up, in terms of welfare there is a slight bias towards the wealthier individuals, which means that consolidation costs were mostly fell on the poor.

Finally, the empirical data observed during the consolidation period can be partially explained by our debt-modeling process. The observed disposable income Gini index path reproduces the humped-shaped curve of the model. As for international flows of capital, the model reproduces the initial deterioration of the Spanish NFA position. However, data does not confirm (at least yet) the asset demand recovery and the reversal in the NFA position, which surpasses the initial steady state level as the economy evolves to the final steady-state equilibrium.

Notes

The dictator Franco died in 20/11/1975, the first election occurred in 15/06/1977 and the new constitution was voted the 27/12/1978.

All policy measures taken during this period resulted from an ample agreement between the most representative political parties and trade unions about wages, employment and social security, signed in October 1977 and known as the Moncloa Pact.

We used the cyclically adjusted primary based on potential GDP. If we use the adjusted series based on the trend GDP, the results are similar, with the primary deficit cyclically adjusted accounting for a debt decrease of 21.41 % points.

In a seminal paper, Barro (1990) incorporates a public sector into a simple, constant return, model of economic growth. The ratio of real public gross investment to real GDP is assumed to correspond to a flow of services identified as the measure of infrastructure services and enters directly into the production function.

Remember that \(r_t\) must be equal for both countries given that complete financial integration holds.

The solution is represented by a sequence of consumption and leisure to infinity \(\{c_t,l_t\}_{t=0}^\infty \).

In a recent paper D’Auria et al. (2010) estimated \(\alpha =0.35\) for the EU15 over the period 1960–2003.

Source: AMECO database, \(k=3.8\).

See Table 2 above.

Decreasing (increasing) \(\vartheta \), from 0.1 to 0 (0.2) induces an increase (decrease) in welfare gains by 12.5 %.

The potential welfare gain corresponds to the final steady-state level of welfare compared to the initial steady state, without taking account for the transition period.

References

Aiyagari S (1994) Uninsured idiosyncratic risk and aggregate saving. Q J Econ 109(3):659–84

Aiyagari S (1995) Optimal capital taxation with incomplete markets, borrowing constraints, and constant discounting. J Polit Econ 103(6):1158–1175

Aiyagari SR, McGrattan E (1998) The optimum quantity of debt. J Monet Econ 42(3):447–69

Alesina A, Perotti R (1995) Fiscal expansions and fiscal adjustments in OECD countries. Econ Policy 21:205–248

Aschauer DA (1989) Is public expenditure productive? J Monet Econ 23(2):177–200

Auerbach A, Kotlikoff L (1987) Dynamic fiscal policy. Cambridge University Press, New York

Barro R (1973) The control of politicians: an economic model. Public Choice 14(1):19–42

Barro RJ (1990) Government spending in a simple model of endogeneous growth. J Political Econ 98(5):S103–S125

Bewley T (1983) A difficulty with the optimum quantity of money. Econometrica 51(5):1485–504

Burriel P, Fernández-Villaverde J, Rubio-Ramírez JF (2010) Medea: a dsge model for the spanish economy. SERIEs 1(1–2):175–243

Castaneda A, Díaz-Giménez J, Ríos-Rull JV (2003) Accounting for the us earnings and wealth inequality. J Polit Econ 111(4):818–857

D’Auria FCD, Havik K, Planas KM, Raciborski R, Roger W, Rossi A (2010) The production function methodology for calculating potential growth rates and output gaps—recent modifications and future research priorities. European Economy Economic Paper 420

de Cos PH, Gómez AL, Maza IA, Martí F (1999) El Sector de las Administraciones Públicas en España. Estudios Econ 68:1–161

De la Fuente A (2000) Mathematical methods and models for economists. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Doménech R, García JR (2002) Optimal taxation and public expenditure in a model of endogenous growth. Topics Macroecon 2(1):1–26

Domingo JA, García JJP, Rojas JA (2014) Public debt monitoring and implicit debt thresholds: an application for the case of Spain. In: XXI Encuentro Economía Pública. Universitat de Girona, p 51

European-Commission (2007) Public Finances in EMU, European Economy N3/2007. European Commission, Brussels

European-Commission (2009) General Government Data: General Government Renevue, expenditurem balance and gross debt. European Commission: Directorate General ECFIN Economic and Financial Affairs, Brussels

Fernandez FC (2005) Una evaluacion macroeconomtrica de la poltica fiscal en espana. Estudios Econmicos, Servicios de Estudios del Banco del Espana 76

Fernandez E, Mauro P (2000) The role of human capital in economic growth: the case of Spain. IMF Working Paper No 00/8

Floden M (2001) The effectiveness of government debt and transfers as insurance. J Monet Econ 48(1):81–108

Floden M (2003) Public saving and policy coordination in aging economies. Scand J Econ 105(3):379–400

Ganelli G, Tervala J (2010) Public infrastructures, public consumption, and welfare in a new-open-economy-macro model. J Macroecon 32(3):827–837. http://ideas.repec.org/a/eee/jmacro/v32y2010i3p827-837.html

Hernández JA, Mauleón I (2005) Econometric estimation of a variable rate of depreciation of the capital stock. Empir Econ 30(3):575–595

Huggett M (1993) The risk-free rate in heterogeneous-agent incomplete-insurance economies. J Econ Dyn Control 17(5–6):953–69

Imrohoroglu A (1989) Cost of business cycles with indivisibilities and liquidity constraints. J Polit Econ 97(6):1364–83

Lane P, Milesi-Ferretti G (2006) The external wealth of nations mark ii: Revised and extended estimates of foreign assets and liabilities, 1970–2004. IMF Working Paper 06/69

Ljungqvist L, Sargent T (2004) Recursive macroeconomic theory. MIT Press, Cambridge

Mendoza EG, Quadrini V, Rios-Rull JV (2009) Financial integration, financial development, and global imbalances. J Political Econ 117(3):371–416

Ni S (1995) An empirical analysis on the substitutability between private consumption and government purchases. J Monet Econ 36(3):593–605. http://ideas.repec.org/a/eee/moneco/v36y1995i3p593-605.html

Rios-Rull J (1999) Computation of equilibria in heterogenous agent models. In: Marimon R, Scott A (eds) Computational methods for the study of dynamic economies: an introduction. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Tauchen G (1986) Statistical properties of generalized method-of-moments estimators of structural parameters obtained from financial market data. J Bus Econ Stat Am Stat Assoc 4(4):397–416

Varga J, Roeger W et al (2014) Growth effects of structural reforms in southern Europe: the case of Greece, Italy, Spain and Portugal. Empirica 41(2):323–363

Viegas M, Ribeiro AP (2013a) Welfare-improving government behavior and inequality in a heterogeneous agents model. J Macroecon 37:146–160

Viegas M, Ribeiro AP (2013) Welfare-improving government behaviour and inequality in a heterogeneous agent model. J Macroecon 37:146–160. doi:10.1016/j.jmacro.2013.05.005

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Viegas, M., Ribeiro, A.P. Welfare and inequality effects of debt consolidation processes: the case of Spain, 1996–2007. SERIEs 6, 479–496 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13209-015-0133-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13209-015-0133-2